Abstract

Transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) receptor kinase inhibitors have a great therapeutic potential. SB431542 is one of the mainly used kinase inhibitors of the TGFβ/Activin pathway receptors, but needs improvement of its EC50 (EC50 = 1 μM) to be translated to clinical use. A key feature of SB431542 is that it specifically targets receptors from the TGFβ/Activin pathway but not the closely related receptors from the bone morphogenic proteins (BMP) pathway. To understand the mechanisms of this selectivity, we solved the crystal structure of the TGFβ type I receptor (TβRI) kinase domain in complex with SB431542. We mutated TβRI residues coordinating SB431542 to their counterparts in activin-receptor like kinase 2 (ALK2), a BMP receptor kinase, and tested the kinase activity of mutated TβRI. We discovered that a Ser280Thr mutation yielded a TβRI variant that was resistant to SB431542 inhibition. Furthermore, the corresponding Thr283Ser mutation in ALK2 yielded a BMP receptor sensitive to SB431542. This demonstrated that Ser280 is the key determinant of selectivity for SB431542. This work provides a framework for optimizing the SB431542 scaffold to more potent and selective inhibitors of the TGFβ/Activin pathway.

Keywords: ALK5, SB431542, ALK2, dorsomorphin, A8301

1. Introduction

TGFβ family proteins (TGFβ, BMPs, Activin/Nodal, GDFs and AMH) are secreted morphogens that signal through heteromeric complexes of transmembrane type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors to orchestrate a wide array of cellular signals in development and disease.

TGFβ family ligand-receptor interaction triggers the formation of specific type I and type II heterotetrameric receptor complexes. The type II receptors then phosphorylate the type I receptors, which in turn phosphorylate down-stream effectors, the receptor-activated Smads (R-Smads). Phosphorylated R-Smads assemble with Smad4, accumulate in the nucleus and regulate transcription via interaction with transcription factor partners [1]. The seven TGFβ family type I receptors cluster in two groups depending on the R-Smad they target. ALK4, TβRI (also referred to as ALK5) and ALK7 induce the phosphorylation of Smad2 and 3; this is called the “TGFβ/Activin pathway”. ALK1, 2, 3 and 6 induce the phosphorylation of Smad1, 5 and 8, and this is referred to as the “BMP pathway” (Fig S1A). In these pathways it is the identity of the activated type I receptor that is critical in defining transcriptional outputs, as the two groups of R-Smads trigger different, and often opposite, cellular responses.

Enhanced signalling output mediated via the intracellular kinase domains of the TGFβ family receptors is important for a variety of pathological processes such as cancer progression, fibrosis, as well as parasitic infection by Trypanosoma cruzi. Therefore, small molecule inhibitors of TGFβ signalling that specifically target the kinase domains have great therapeutic potentials.

Multiple inhibitors are commonly used to dissect the myriad biological and pathological functions of TGFβ family cytokines. During the first attempt to find inhibitors for TβRI, by using a TβRI kinase assay coupled to compound screening, Callahan et al. found that 2,4,5-substituted imidazoles could be potent inhibitors [2]. This resulted in a series of 2,4,5-substituted imidazoles [2-4]. Later on, virtual small molecules screening aimed at finding new molecules targeting the TβRI ATP-binding pocket yielded a series of 2,4,5-substituted pyrazole inhibitors [5, 6]. 2,4,5-substituted imidazoles and pyrazoles are the two main inhibitor families used to inhibit the TGFβ/Activin pathway (Fig S1).

Recently, multiple inhibitors belonging to the substituted-imidazole group (SB431542 and its derivatives SB505124 or SB525334) or substituted-pyrazole group (LY364947 and its derivative A8301) have been benchmarked in a panel of 123 kinases [7]. This confirmed that these kinase inhibitors are specifically targeting the TGFβ- but not the BMP-pathway receptors, which makes them invaluable. However, the molecular determinants conferring inhibitor specificity of those inhibitors toward the TGFβ/Activin but not the BMP pathway are unknown. Understanding how this specificity is regulated is needed to enhance the usefulness of these pathway specific inhibitors, through chemical engineering.

We have solved the structure of SB431542 bound to the TβRI protein kinase domain, with the aim of understanding the molecular basis for SB431542 inhibitor specificity. The structure enabled a systematic mutational analysis of TGFβ- and BMP-receptors (TβRI and ALK2), coupled with specific TGFβ- or BMP-receptor activity readouts to discern the basis for inhibitor specificity. We have discovered that the gatekeeper residue S280 in TβRI is the key determinant for the selectivity of both SB431542 and A8301.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein expression and purification

The TβRI kinase domain (residues 200-503) was cloned into a pFastBac-HTa vector, expressed in Sf9 cells and purified using nickel affinity chromatography. The 6×His purification tag was cleaved overnight by incubation with TEV protease at 4 °C. TβRI was then purified using an S75 Superdex gel filtration column pre-equilibrated in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT.

2.2. Crystallization, data collection and structure determination

TβRI was mixed with SB431542 at final concentrations of 0.25 mM and 1 mM respectively and incubated on ice for 60 min prior to crystallisation. Crystals were grown using the hanging drop vapour diffusion method by mixing 1.5 μl of TβRI-SB431542 complex with 1.5 μl of mother liquor containing 100 mM imidazole pH 8.0 and 10% PEG 8000. Full-sized crystals of the TβRI-SB431542 complex grew after 5 days. Crystals were cryoprotected with mother liquor supplemented with 25% glycerol (v/v) before flash freezing in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at NE CAT beamline 24-ID-C. The structure was solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP [8] and the TβRI structure (PDBID 1PY5, [9]) as a search model. The structure was refined by iterative rounds of refinement with REFMAC [10] and manual model building with the program COOT [11].

2.3. Alignment and Mutagenesis

Sequences alignments were performed using MUSCLE [12] and edited using ALINE [13]. Mutants of ALK2ca and TβRIca were generated using conventional site directed mutagenesis technique. Each mutant was sequenced-verified.

2.4. Reporter gene constructs, expression plasmids and inhibitors

Reporter plasmids pGL3 (BRE)-luc was kindly provided by Dr P. ten Dijke (Leiden University Medical Center, Netherlands). 3TP-lux, TβRI and ALK2 were previously generated in the lab. SB431542 and dorsomorphin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; A8301 from Tocris.

2.5. Luciferase activity assay

NIH-3T3 cells were seeded in 24 well plates for 24h, then transfected in Opti-MEM using lipofectamine and PLUS reagent (Invitrogen) with 0.1 μg pGL3 (BRE2)-luc or 0.2 μg p3TP-luc, 0.05 μg of pCMV5 β-gal and 0.05 μg of either pCMV-GFP or a vector expressing ALK2 or TβRI. Four hours after transfection, cells were treated with inhibitors (SB431542, A8301 or dorsomorphin) at the indicated concentrations for 15h. Cells were lysed, then Firefly luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured, using a luminometer (Berthold) or a plate reader (Perkin-Elmer), respectively [14]. Values of fold activation were calculated as relative luciferase activity compared with untreated cells. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation calculated from data derived from 3 individually transfected wells of NIH-3T3 cells.

2.6. Protein expression and Western blotting

293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing ALK5ca and ALK5ca S280T, by calcium phosphate. 48h after transfection, cells were lysed in 0.1% (v/v) TNTE and separated on SDS-PAGE. After transfer on nitrocellulose membrane, the membranes were probed with anti-Phospho-Smad2 (Cell Signalling, 1/2500), anti-Smad2 (Cell Signalling, 1/2500) anti-HA (Roche, 1/5000) and anti-Actin (Sigma, 1/10,000) antibodies.

3. Results

3.1. Structure of the TβRI-SB431542 complex

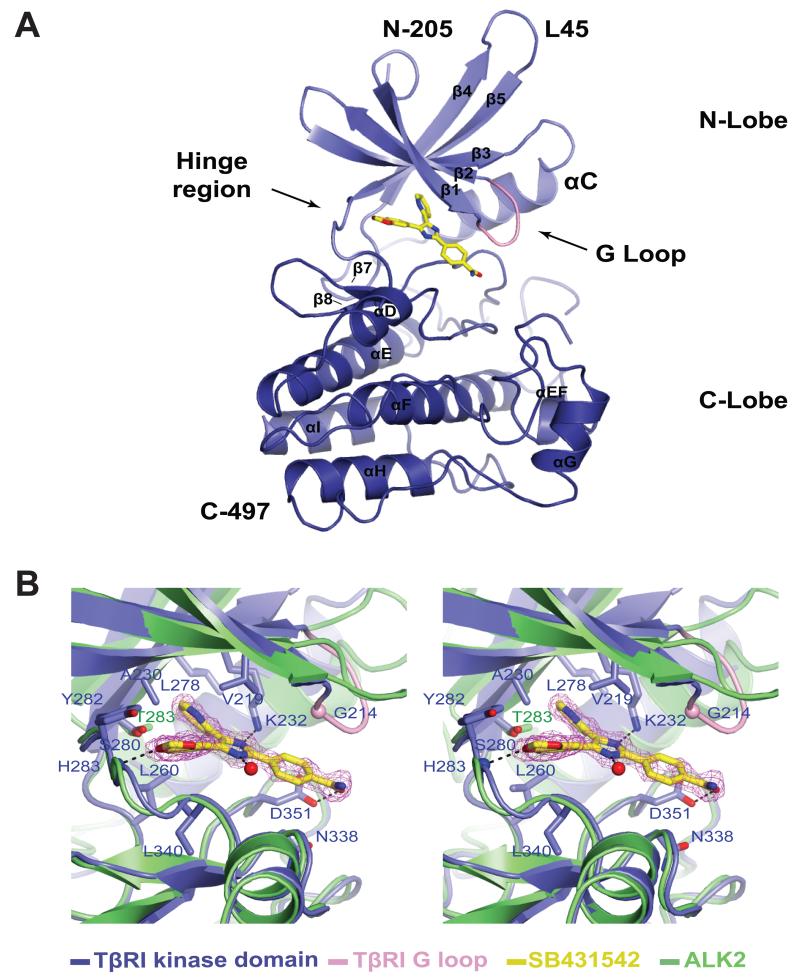

To investigate the basis for selectivity of SB431542 towards TGFβ pathway receptors (EC50 = 1 μM) versus BMP pathway receptors (no inhibition at 20 μM), we co-crystallized SB431542 bound to TβRI kinase domain (residues 200-503). Diffraction data collection to 1.7 Å resolution, structure solution by molecular replacement and refinement, resulted in a final model with good statistics (Table 1). Residues 370-371 (within the activation segment) and 497-503 (corresponding to the C-terminus) were disordered and are absent from the final model. TβRI displays the classical kinase domain organisation comprising a small N-terminal lobe and a larger C-terminal lobe (Fig 1A). The TβRI activation loop (region between DFG and APE motifs) attains the extended conformation found in active protein kinases [15]. The Leu residue of the DLG motif (equivalent to the DFG motif in most kinases) assumes the so-called “DFG in” conformation [16]. TβRI in complex with SB431542 resembles the TβRI kinase conformation reported in the FKBP12-TβRI complex (RMSD 0.3 Å over 207 Cα atoms) [17]. Clear electron density was observed for the SB431542 compound (see unbiased |Fo| - |Fc| electron density maps in Fig 1B). SB431542 has a heterocyclic ring structure (Fig S1) and acts as a type I kinase inhibitor [18] by occupying the purine (ATP) binding region and adjacent hydrophobic sites near the hinge region; the latter defined as the linker between the N– and C-terminal kinase lobes (Fig 1A). The first residue of the hinge region is referred to as the gatekeeper residue, which often fills a hydrophobic pocket adjacent to the ATP purine-binding site [19]. TβRI however contains a small residue at the gatekeeping position (S280), thus allowing for the hydrophobic pyridinyl ring of SB431542 to be comfortably accommodated within this pocket (Fig 1B). The position of the pyridinyl ring adjacent to the gatekeeper residue is further stabilised through hydrophobic interactions via residues A230 (β3 sheet), L260 (αC-β5 loop) and L278 (β4 sheet). L260 and A230 contact both the pyridinyl and benzodioxol rings, which adopt a non-co-planar conformation (Fig 1B).

Table 1. Data collection, structure determination and refinement statistics for TβRI-SB431542 complex.

| Space group | P21 |

| Unit cell | a = 41.8 Å, b = 77.7 Å, c = 90.1 Å α = β = γ = 90° |

| Number of molecules/asu | 1 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30 – 1.7 (1.76-1.70) |

| Observed reflections | 183820 |

| Unique Reflections | 31955 (3236) |

| Redundancy | 5.8 (5.6) |

| I/σI | 39.8 (5.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.8 (99.8) |

| R sym | 0.085 (0.0383) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.172/0.205 |

| Rms deviations | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.009 |

| Angles (°) | 1.23 |

| B-factor rmsd (Å2) Backbone bonds | 0.96 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 19.85 |

| Ligand (SB431542) | 15.05 |

| Water | 29.28 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%) | |

| Most favored region | 97.9% |

| Additional allowed region | 2.1% |

| Disallowed region | 0.0% |

Values for the highest resolution shell are given in parentheses

asu, = asymmetric unit

Figure 1. Crystal structure of TβRI-SB43154 complex.

(A) Structure of TβRI Kinase domain (blue) in complex with SB431542. The structure of SB431542 (yellow) is shown as sticks occupying the ATP binding cleft between the kinase N- and C-lobes. (B) Magnified stereo view of SB431542 compound coordination in the binding cleft showing residues contacting SB431542 and the conservation of the ATP binding cleft between TGFβ and ALK2. Hydrogen bonds are represented by dashed lines and a water molecule is depicted as a red sphere.

The benzodioxol ring of SB431542 is sheltered by hydrophobic residues A230, L260, Y282 (hinge region) and L340 (β7 sheet) (Fig 1B). A hydrogen bond links the benzodioxol oxygen of SB431542 and the amide nitrogen of H283 from the hinge region of the TβRI kinase domain (Fig 1B), a feature common to many ATP competitive kinase inhibitors. The classical ion pair between K232 (VAIK motif) and E245 (helix αC), reflective of an active-like kinase conformation, is maintained and places K232 in hydrogen bonding distance to the imidazole ring of SB431542, which is also stabilised by V219 (β7 strand) through hydrophobic interactions, as well as by coordination by an ordered water molecule (Fig 1B). The SB431542 benzamide ring, sandwiched between the glycine-rich (Gly-rich, GXGXXG) loop and the activation segment, is coordinated in part through hydrogen bonding to D351 (Fig 1B). Compared to the other cyclic moieties of SB431542, the benzamide ring appears loosely coordinated. The main SB431542 contacts contributing to binding involve the pyridinyl, benzodioxol and imidazole moieties interacting with residues from the hinge region and N- and C-lobes of TβRI.

3.2. The gatekeeper residue is responsible for TGFβ selective inhibition by SB431542

To understand why SB431542 selectively inhibits TβRI but not its closely related counterpart ALK2, we superimposed the structure of ALK2 kinase domain (PDBID 3H9R) onto the structure of TβRI bound to SB431542, and looked for differences in residues contributing to SB431542 binding. Inspection of the SB431542-kinase contacts revealed that of the 12 residues directly contacting the bound inhibitor, only the gatekeeper residue S280 differs between ALK2 and TβRI. S280 is conserved in all the TGFβ/Activin pathway receptors, while it is replaced by T283 in all BMP pathway receptors (Fig S2).

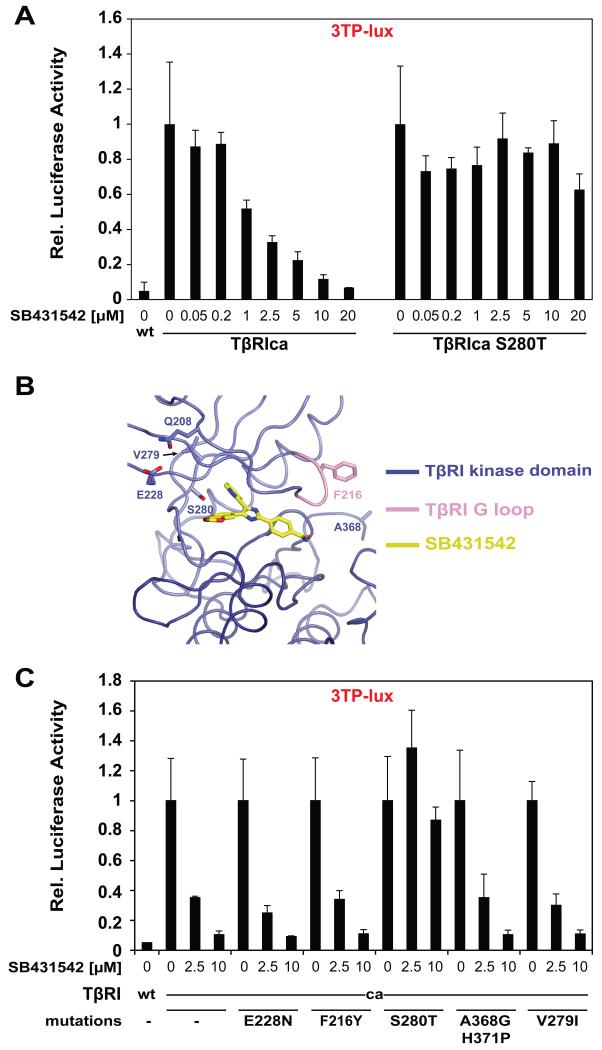

To assess if S280 indeed contributes to selective inhibitor binding we mutated this position to threonine (its counterpart in ALK2), and tested for the ability of SB431542 to inhibit TβRI. We used a constitutively active form of TβRI (TβRIca, T204D), as our goal was to analyse the effect of the mutation on the kinase activity, and not on ligand binding or on type I/II transactivation. We co-transfected TβRIca with a reporter gene (3TP-Lux) that is specifically activated by Smad2 and 3, the downstream targets of TβRI [20]. TβRIca strongly activated 3TP-lux when compared to the wild type TβRI (>15 fold) (Fig 2A). This activation was potently suppressed by SB431542 in a dose dependent manner and TβRIca activity was diminished to basal levels at 20 μM SB431542 (Fig 2A). We then tested a TβRIca S280T mutant in the presence of SB431542. We found that TβRIca (S280T) strongly activated 3TP-lux, but unlike the WT receptor, was completely resistant to SB431542 inhibition when tested up to 20 μM (Fig 2A). These results indicate that S280 confers selectivity in SB431542-mediated inhibition of TβRI-like kinases. We note that both TβRIca and TβRIca (S280T) have similar expression levels as shown by Western blotting (Fig S3).

Figure 2. TβRIca S280T mutant is resistant to SB431542.

(A) NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with 3TP-lux. β-gal and constructs expressing TβRI wt, or TβRIca with the indicated ATP binding cleft mutations. After treatment with various doses of SB431542, Luciferase activity was measured and results were normalized to β-gal activity. (B) Worm representation of the N-lobe of TβRI showing residues selected for mutagenesis based on lack of conservation among TGFβ type I receptors (see also sequence alignment in Fig S2). (C) The experiment was conducted as in (A), with the indicated constructs.

We next explored the possibility that additional residues could also be important for SB431542 selective inhibition. Sequence alignment of TGFβ and BMP pathway receptor kinases revealed non-conserved residues as possible contributors to TβRI-SB431542 specificity (Fig S2). Namely Q208, F216, E228, V279, A368 and H371 corresponding to L211, Y219, N231, I282, G371 and P374 in ALK2 (Fig 2B and S2). Although not in direct contact with SB431542 (Fig 2B), we questioned if these differing residues contributed indirectly to the selective inhibition of TβRI by SB431542. Additionally, the orientation of F216 is flipped ≈180° toward the outside of the binding pocket in the presence of SB431542 (compared to ALK5 apo structure PDBID 11AS - Fig S4A). Assuming the same side chain flip will occur in ALK2, the corresponding residue Y219 would be predicted to directly contact SB431542 (Fig S4A). However, substitution of TβRIca residues to their ALK2 counterparts, F216Y, E228N, V279I and A368G-H371P, all yielded mutant receptors that were equally sensitive to inhibition by 5 μM of SB431542 (Fig 2C). This suggests that these differing residues do not contributed to TβRI selective inhibition by SB431542. Analysis of combinational mutations further revealed no additional amino acids or group of amino acids that regulated SB431542 specificity (Fig S4B).

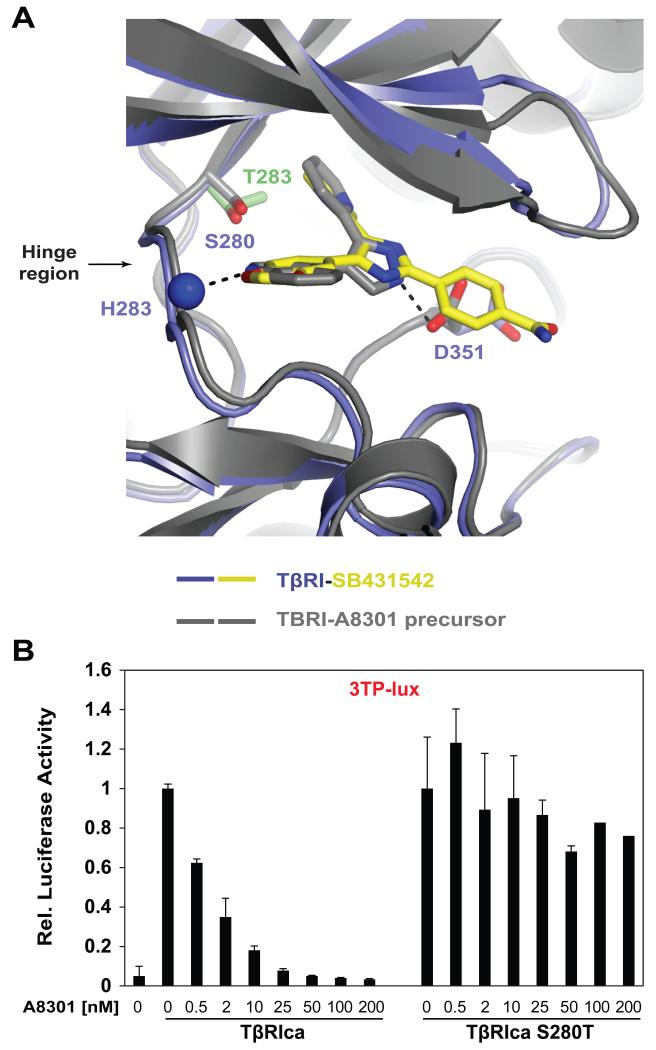

3.3. TβRIca (S280T) is resistant to A8301 inhibition

Since the gatekeeper residue defines sensitivity to SB431542, we next investigated if the same residue (S280) also regulates specificity to substituted-pyrazole compounds. Superimposition of TβRI-SB431542 complex with the structure of TβRI bound to LY364947 (precursor of A8301 - PDBID 1PY5) [9], revealed similarities of TβRI - inhibitor binding (Fig 3A). The two TβRI structures show little overall difference (RMSD of 0.3 Å over 293 Cα atoms) with the exception of a shift in the orientation of the side chain of D351 (D351 interacts with the benzamide ring of SB431542 and the imidazole ring of LY364947 - Fig 3). Comparison of the two structures led us to hypothesize that the S280T mutation would also render TβRIca resistant to A8301 inhibition. Indeed, A8301 inhibited TβRIca in a dose dependent manner with complete inhibition at 50 nM A8301 (Fig 3B), while TβRIca (S280T) was resistant to A8301 inhibition under the same conditions (Fig 3B). These findings demonstrate the importance of S280 in conferring selectivity of substituted-imidazole and -pyrazole small molecule inhibitors towards TβRI-like kinases.

Figure 3. Similarities between A8301 and SB431542.

(A) Magnified ribbon representation of superimposed co-crystal structures of TβRI- A8301 and TβRI-SB431542 complexes. Dashed lines: Hydrogen bonds; blue sphere: amide nitrogen of His283. (B) NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with 3TP-lux, β-gal and indicated constructs. Dose response was determined by treating cells with varying concentrations of A8301 compound.

3.4. T283S mutation renders ALK2 sensitive to SB431542

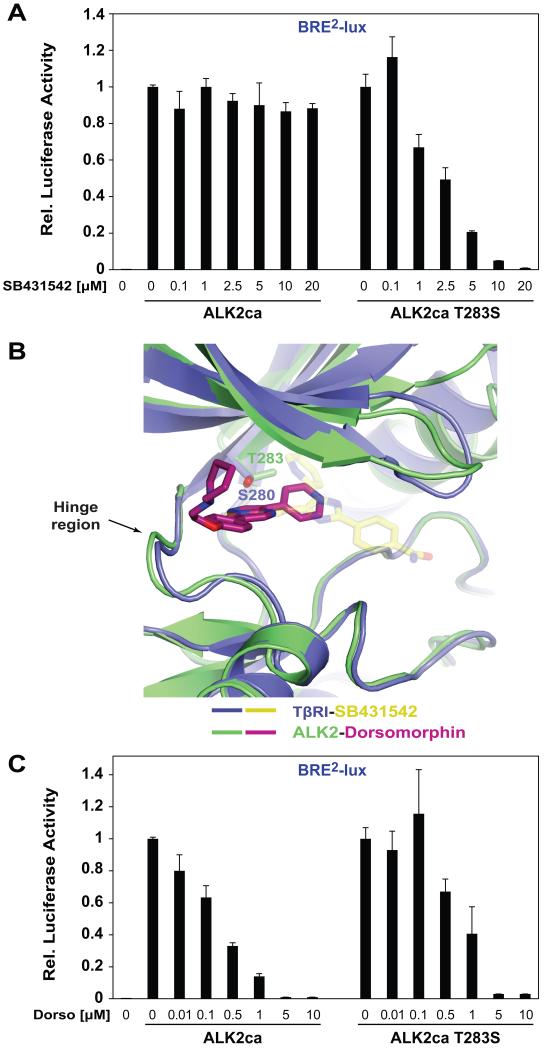

ALK2 has a threonine at the gatekeeper position and is resistant to SB431542, therefore, we mutated the ALK2 gatekeeper residue T283 to the Ser residue found in TβRI and assessed sensitivity to SB431542. For this we used a constitutively active ALK2 mutant (ALK2ca, Q207D) and a BMP reporter gene (BRE2-luc) (Fig S1A) [21]. We found that the single T283S substitution of the ALK2 gatekeeper residue resulted in ALK2ca inhibition by SB431542 (Fig 4A). Notably, the EC50 of SB431542 for ALK2ca (T283S) was similar to the EC50 of SB431542 on TβRI activity (EC50 ALK2ca T283S = 2.5 μM, EC50 TβRIca = 1 μM). These results confirm that the gatekeeper residue in TGFβ family receptors is critical for inhibitor specificity among the compounds we tested.

Figure 4. ALK2 gatekeeper residue mutant T283S is sensitive to SB431542.

(A) NIH-3T3 cells were transfected with BRE-Luc, β-Gal and plasmid expressing ALK2ca or ALK2ca T283S. Dose response was determined by treating cells with varying concentrations of SB431542 compound (A). (B) Superimposition of the ATP binding cleft of TβRI-SB431542 and ALK2-dorsomorphin complexes. (C) The experiment was performed as in (A), but with dorsomorphin.

To further delineate the molecular basis for specific TGFβ versus BMP receptor inhibition, we compared the binding mode of SB431542 to TβRI with that of the BMP inhibitor dorsomorphin to ALK2 (PDBID 3H9R) (Fig 4B). We examined the co-crystal structure of ALK2 in complex with dorsomorphin and observed that in contrast to TβRI-SB431542 structure, dorsomorphin does not contact the gatekeeper position but instead is mainly coordinated by hydrogen bonds with H286 in the hinge region of the ALK2 kinase domain (Fig 4B). Thus, we hypothesized that inhibition by dorsomorphin would not be affected by the T283S mutation. Consistent with this notion, dorsomorphin comparably inhibited both ALK2ca T283S and ALK2ca in the BMP pathway reporter assay (complete inhibition at 5 μM) (Fig 4C). Moreover, none of the TβRIca mutants generated (see Fig 2C and Fig S4B) was sensitive to dorsomorphin (data not shown).

4. Discussion

In this study we show that the selective inhibitory function of the substituted-imidazole SB431542 on TGFβ- versus BMP-signalling depends on serine 280 at the gatekeeping position within the ATP binding cleft of the kinase domain. Mutation of this serine to threonine (S280T) conferred complete resistance of TβRI to inhibition by SB431542. Furthermore, a reciprocal mutation of threonine to serine at this position in ALK2 (T283S) rendered ALK2 sensitive to SB431542. Moreover, we showed that the gatekeeper residue was also important for the substituted-pyrazole A8301 inhibition of TβRI. A number of co-crystal structures of TβRI kinase domain-inhibitors with several types of core moieties are available. To our knowledge, all co-crystallized inhibitors appear to occupy the available space in the ATP-binding back-pocket of TβRI (Fig S5). This suggests that S280 could be a key determinant of most TβRI inhibitors.

Altogether, our structural and functional studies point out the importance of having a small gatekeeper residue in TβRI that allows for SB431542 binding. Interestingly, 11 out of the 518 protein kinases have residues with small or no side chains (e.g. Ser, Ala and Gly) at the gatekeeper position [Kinase Sequence Database (http://sequoia.ucsf.edu/ksd/)]. Six protein kinases have serine as a gatekeeper, three of which are TGFβ family kinases sensitive to SB431542 inhibition (ALK4, TβRI and ALK7) and the other three are c-Abl, RETGC-1 and STRADβ. Of these, c-Abl is not inhibited by SB431542 suggesting that other binding pocket determinants, in addition to the small gatekeeper residue, contribute to the selectivity of SB431542 inhibition [7, 22].

Substituted-imidazole TGFβ pathway inhibitors (SB4321542 and its close analogue SM16 - Fig S1) have been successfully used in animal disease models for fibrosis, Chagas disease and cancer. Usage of SM16 resulted in decreased fibrosis and decreased myofibroblast induction in the lung [23], kidney [24], liver [25] or blood vessels [4]. SB431542 was successfully used in a mouse model of Chagas disease, which results from the infection of cardiomyocytes by Trypanozoma cruzi parasites and led to decreased parasitaemia and prevented heart damage [26]. Finally, SM16 inhibited primary tumour progression and metastasis in mouse breast cancer and mesothelioma tumour models [27, 28]. Moreover, a substituted-pyrazole, LY2157299 [29], is being tested in phase II on patients with hepatocellular carcinomas (http://clinicaltrials.gov).

These studies bear great promises for therapeutical use of TGFβ/Activin pathway inhibitors based on substituted-imidazole or -pyrazole scaffolds. Our results pave the way forward for structural-based drug design aimed at improving the selectivity and potency of TGFβ/Activin pathway inhibitors, which will help their translation to the clinic.

5. Conclusions

-

-

Mutation of the gatekeeper residue of TβRI (Ser280) to the equivalent residue in ALK2 (Thr283) renders TβRI insensitive to SB431542, a substituted imidazole selective TβRI inhibitor.

-

-

The Ser280Thr mutant of TβRI is also insensitive to A8301, a substituted pyrazole selective TβRI inhibitor.

-

-

Analysis of the deposited structures of TβRI in complex with small molecules inhibitors suggests that Ser280 is a key determinant of most of the selective TβRI inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Hinck and Gerald Gish for critically reviewing this manuscript.

Financial disclosure

Supported by funds from CIHR to JLW (MOP14339) and FS (MOP36399). LD is recipient of a CIHR Fellowship and EZ is a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellow. JLW is an HHMI International Scholar and CRC Chair in Systems Biology and FS is a CRC Chair in Structural Biology of Signal Transduction. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Accession codes

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code PDBID: 3TZM.

Supplementary Information contains 5 figures.

References

- [1].Attisano L, Wrana JL. Science. 2002;296:1646–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1071809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Callahan JF, Burgess JL, Fornwald JA, Gaster LM, Harling JD, Harrington FP, Heer J, Kwon C, Lehr R, Mathur A, Olson BA, Weinstock J, Laping NJ. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2002;45:999–1001. doi: 10.1021/jm010493y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Callahan JF, Harling JD, Gaster LM, Reith AD, Laping NJ, Hill CS. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fu K, Corbley MJ, Sun L, Friedman JE, Shan F, Papadatos JL, Costa D, Lutterodt F, Sweigard H, Bowes S, Choi M, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Arduini RM, Sun D, Newman MN, Zhang X, Mead JN, Chuaqui CE, Cheung HK, Cornebise M, Carter MB, Josiah S, Singh J, Lee WC, Gill A, Ling LE. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28:665–671. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Singh J, Chuaqui CE, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Lee WC, Pontz T, Corbley MJ, Cheung HK, Arduini RM, Mead JN, Newman MN, Papadatos JL, Bowes S, Josiah S, Ling LE. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2003;13:4355–4359. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tojo M, Hamashima Y, Hanyu A, Kajimoto T, Saitoh M, Miyazono K, Node M, Imamura T. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vogt J, Traynor R, Sapkota GP. Cellular signalling. 2011;23:1831–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vagin A, Teplyakov A. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sawyer JS, Anderson BD, Beight DW, Campbell RM, Jones ML, Herron DK, Lampe JW, McCowan JR, McMillen WT, Mort N, Parsons S, Smith EC, Vieth M, Weir LC, Yan L, Zhang F, Yingling JM. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2003;46:3953–3956. doi: 10.1021/jm0205705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Edgar RC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bond CS, Schuttelkopf AW. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65:510–512. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909007835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Labbe E, Silvestri C, Hoodless PA, Wrana JL, Attisano L. Mol Cell. 1998;2:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nolen B, Taylor S, Ghosh G. Molecular cell. 2004;15:661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zuccotto F, Ardini E, Casale E, Angiolini M. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2010;53:2681–2694. doi: 10.1021/jm901443h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Huse M, Chen YG, Massague J, Kuriyan J. Cell. 1999;96:425–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liu Y, Shah K, Yang F, Witucki L, Shokat KM. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 1998;6:1219–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wrana JL, Carcamo J, Attisano L, Cheifetz S, Zentella A, Lopez-Casillas F, Massague J. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1992;57:81–86. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1992.057.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Korchynskyi O, ten Dijke P. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:4883–4891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Karaman MW, Herrgard S, Treiber DK, Gallant P, Atteridge CE, Campbell BT, Chan KW, Ciceri P, Davis MI, Edeen PT, Faraoni R, Floyd M, Hunt JP, Lockhart DJ, Milanov ZV, Morrison MJ, Pallares G, Patel HK, Pritchard S, Wodicka LM, Zarrinkar PP. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26:127–132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bonniaud P, Margetts PJ, Kolb M, Schroeder JA, Kapoun AM, Damm D, Murphy A, Chakravarty S, Dugar S, Higgins L, Protter AA, Gauldie J. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;171:889–898. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-612OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Grygielko ET, Martin WM, Tweed C, Thornton P, Harling J, Brooks DP, Laping NJ. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2005;313:943–951. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].de Gouville AC, Boullay V, Krysa G, Pilot J, Brusq JM, Loriolle F, Gauthier JM, Papworth SA, Laroze A, Gellibert F, Huet S. British journal of pharmacology. 2005;145:166–177. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Waghabi MC, de Souza EM, de Oliveira GM, Keramidas M, Feige JJ, Araujo-Jorge TC, Bailly S. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2009;53:4694–4701. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00580-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rausch MP, Hahn T, Ramanathapuram L, Bradley-Dunlop D, Mahadevan D, Mercado-Pimentel ME, Runyan RB, Besselsen DG, Zhang X, Cheung HK, Lee WC, Ling LE, Akporiaye ET. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2099–2109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Suzuki E, Kim S, Cheung HK, Corbley MJ, Zhang X, Sun L, Shan F, Singh J, Lee WC, Albelda SM, Ling LE. Cancer research. 2007;67:2351–2359. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bueno L, de Alwis DP, Pitou C, Yingling J, Lahn M, Glatt S, Troconiz IF. European journal of cancer. 2008;44:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.