Abstract

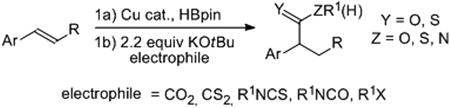

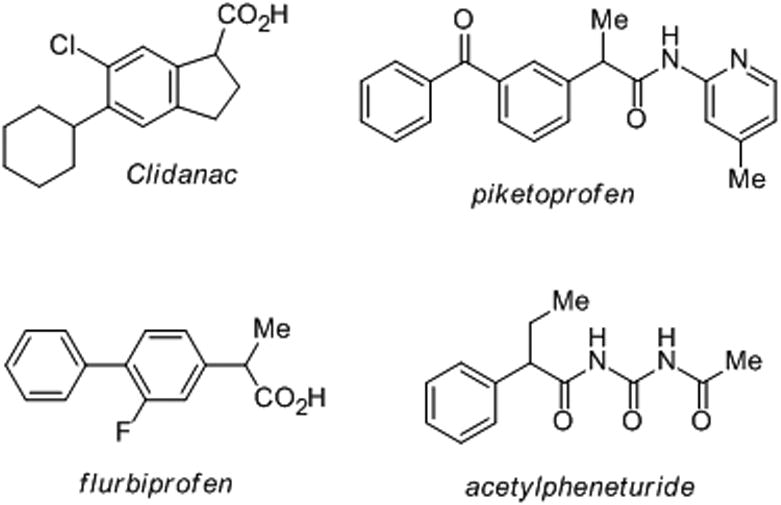

The facile generation of benzyl anion equivalents from styrenes has been achieved. A Cu-catalyzed hydroboration is used in conjunction with sterically-induced cleavage of the C-B bond with tBuOK. Quenching this reactive intermediate with heterocumulene electrophiles, including CO2, CS2, isocyanates and isothiocyanates, yields benzylic C-C bond formation. The utility of this methodology was demonstrated in a synthesis of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (+)-flurbiprofen.

Keywords: carboxylation, cleavage reaction, benzyl anion, Cu catalysis, cascade reactions

Introduction

The reaction of a carbanion with an electrophile is one of the most general approaches employed for the formation of new C-C bonds.[1] However, certain types of carbanionic species are difficult or inconvenient to prepare; hence, many synthetic chemists opt for more indirect approaches to construct the desired bonds. An excellent example is the benzyl anion, which could undergo reaction with heterocumulene electrophiles to yield a number of valuable bioactive molecules (Figure 1). However, the generation of these reactive species is far from trivial and suffers from more than just the expected functional group incompatibility. Direct deprotonation at a benzylic position often leads to competing metallation of the aromatic ring, while the oxidative additions of metals, including Mg, Zn, Cd and Mn, to benzyl halides are problematic due to the competitive formation of bibenzyl products.[2],[3] Thus, the formation of benzyl carbanions has traditionally relied either on the use of toxic main-group precursors, including benzylselenides, benzylstannanes, benzyltellurides and benzylmercury compounds, or on the cleavage of benzyl oxygen and benzyl-sulfur bonds with lithium.[2g,],[4],[5]

Figure 1.

Bioactive molecules containing benzylic functionalization.

Results and Discussion

A more convenient and environmentally friendly approach would involve generating a benzyl anion from an olefin precursor, perhaps via the intermediacy of a benzyl boronic ester. This could minimize single-electron pathways and the subsequent formation of homocoupling by-products that plague current methods. Benzyl carbons have been previously functionalized by the treatment of benzyl boronic esters with strong bases to give borates, which undergo subsequent reaction with a variety of electrophiles.[6] These elegant methods developed by Matteson, Aggarwal, Crudden and others rely on the use of pyrophoric and, in some cases, very specific, organolithium bases. The desired products cannot be accessed directly from the styrene; however, the transfer of the chirality from an enantioenriched boronic ester to the product with excellent fidelity is a nice feature of these systems.[6] In our case, the products of interest contain highly acidic protons at the benzylic position, which obviates the need for an asymmetric approach. In fact, on an industrial scale, flurbiprofen and ibuprofen are prepared and utilized as the racemates. If resolution is necessary, flurbiprofen can be treated with (R,R)-thiomicamine and the undesired enantiomer recycled.[7] Currently, this approach is much more economical than utilizing existing asymmetric syntheses of the molecule.

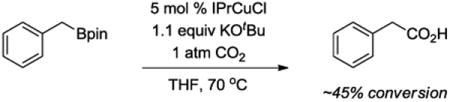

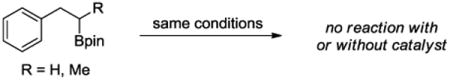

We hypothesized that C-C bond formation at a benzyl carbon might be facilitated under mild conditions using the combination of a bulky boronic ester and a bulky alkoxide base. Attack of the base on the boron of the boronic ester would generate the boronate, which could then undergo heterolytic C-B bond cleavage to generate a highly reactive benzyl carbanion.[8] Initial proof-of-principle was provided by treatment of a primary benzylic boronic ester with potassium tert-butoxide in the presence of CO2 (eq 1). Continued experimentation deomonstrated that the Cu species was not necessary to promote the carboxylation reaction. In addition, this transformation proved to be chemoselective, as a non-benzylic boronic ester did not yield the desired carboxylic acid product (eq 2). In this paper, we report the generation and C-C bond-forming reactions of highly reactive benzyl anion equivalents from styrenes using a one-pot Cu-catalyzed hydroboration followed by simple treatment with KOtBu and a heterocumulene electrophile.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

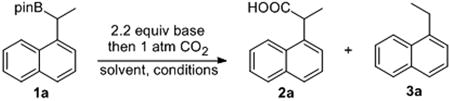

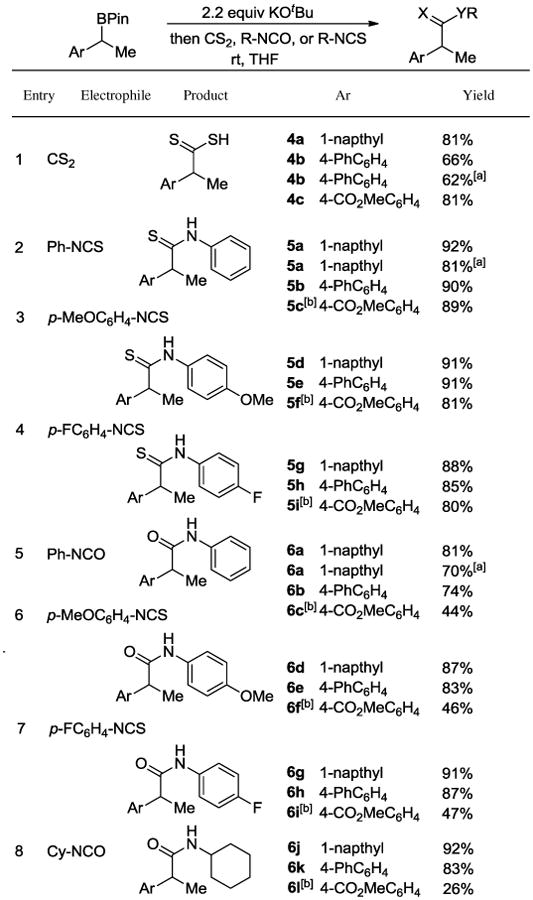

A secondary pinacol-based boronic ester 1a, accessed from a Cu-catalyzed Markovnikov hydroboration of 1-vinylnapthalene, was chosen for initial studies to determine if sterically induced C-B bond cleavage to yield a benzyl anion could be accomplished (Table 1).[9] Yun and co-workers have described an enantioselective version of this highly regioselective hydroboration reaction, but we were able to employ CuCl in conjunction with a bis(diphenylphosphino)benzene (dppbz) ligand to accomplish the racemic reaction (see the Experimental and Supporting Information for further details). CO2 was employed as the electrophile, as this readily available and inexpensive C1 source would lead to the formation of phenylacetic acids such as 2a.[10] The identity of both the anion and the cation proved important. NaOtBu (entry 1) gave incomplete conversion, while LiOtBu was completely ineffective (data not shown). KOtBu was the superior base (entries 5-10), with KHMDS (entry 2) giving none of the desired 2a. The addition of the appropriate crown ethers to the reaction mixture did not improve the results. A variety of fluoride sources known to form boronate complexes from boronic esters (KF, TBAF, TASF and CsF, entry 3) were also unsuccessful, perhaps due to their lack of steric bulk. The optimal solvents were ethereal in nature, with diethyl ether at -40 °C resulting in an 86% yield of 2a (entry 5) and THF a 75% yield (entry 6). Dioxane and DME gave 2a in moderate yields, but were not as effective as THF or diethyl ether. Noticeable temperature effects were also apparent, particularly in relation to the amount of protodeboronated 3a that was produced in the reaction.[11]

Table 1.

Initial optimization of the benzylic anion formation and quenching with CO2.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Entry | Base | Solvent | Temperature | 1a:2a:3a[a] |

| 1 | NaOtBu | THF | rt | 65:17:trace |

| 2 | KHMDS | THF | rt | 70:0:30 |

| 3 | CsF | THF | rt | 100:0:0 |

| 4 | KOtBu | hexane | 0 °C | 65:16:18 |

| 5 | KOtBu | Et2O | -40 °C | trace:86:10 |

| 6 | KOtBu | THF | -40 °C | 9:75:16 |

| 7 | KOtBu | THF | -78 °C | 25:62:12 |

| 8 | KOtBu | THF | -15 °C | trace:60:23 |

| 9 | KOtBu | THF | -0 °C | trace:56:26 |

| 10 | KOtBu | THF | rt, -78 °C | 0:82:trace |

1H NMR yields based on bibenzyl as the internal standard.

Although conversion to 2a was observed at temperatures as low as -78 °C (entry 7), complete conversion of the starting material did not occur until the temperature reached -15 °C (entry 8). The increase in conversion at higher temperatures (entries 8-9) came at the expense of increased amounts of by-product 3a, which resulted from the deprotonation of the acidic proton of the product 2a by unreacted anionic species present in the mixture. With this protodeboronation pathway in mind, the optimal reaction conditions utilized base-substrate mixing at room temperature followed by cooling the solution to -78 °C before addition of CO2. This minimized the undesired protodeboronation and provided higher and more consistent yields in subsequent studies.

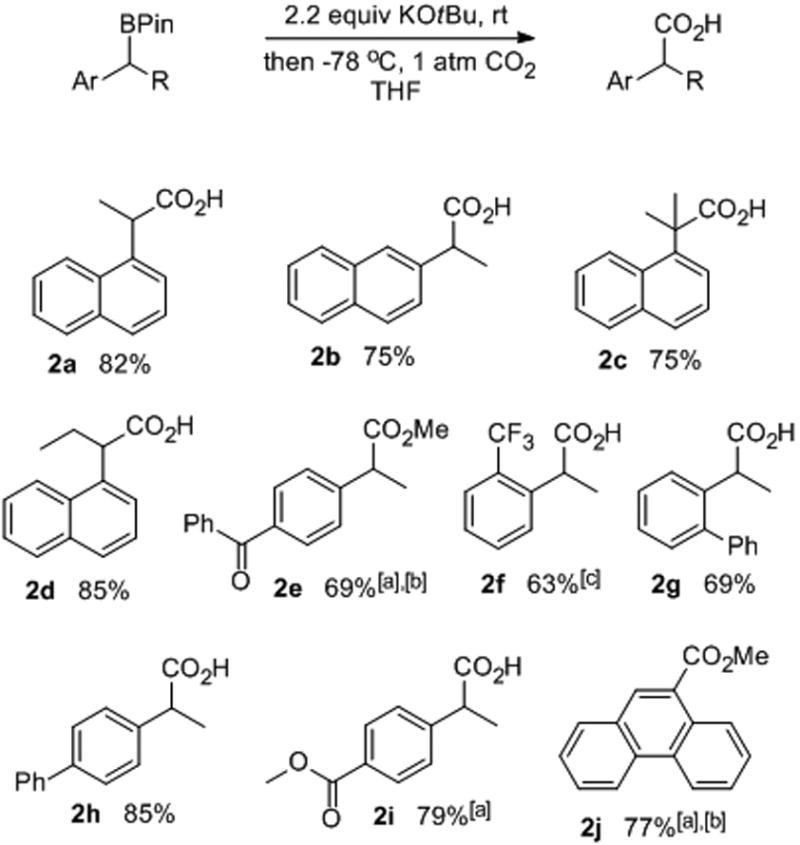

With an optimized method in hand for the carboxylation of the benzylic boronic esters, the scope of the reaction was explored. Both 1- and 2-naphthylene-derived boronic esters 1a and 1b (Table 2, entries 1 and 2) were converted to the corresponding carboxylic acids in 82% and 75% yields, respectively. A tertiary boronic ester 1c (entry 3) was converted smoothly to the tertiary carboxylic acid 2c in good yield. It was not necessary to utilize a terminal olefin, as additional substitution at the β-position of the olefin was tolerated (entry 4). Other aromatic systems, including those based on biphenyl systems (entries 7 and 8), successfully gave the carboxylic acids. The success of the carboxylation was greatly improved using electron-withdrawing groups on the styrenyl and phenanthryl systems (entries 5-10). Ketone and ester groups survived the reaction conditions, provided the temperature of base-substrate mixing was lowered (entries 5 and 9).

Table 2.

Substrate scope for the sterically induced C-B bond cleavage using CO2 as the electrophile.

|

The entire reaction was performed at -78 °C.

The acid was esterified prior to isolation.

The entire reaction was performed at -45 °C.

The simplicity of the carboxylation conditions allowed it to be telescoped with a Cu-catalyzed hydroboration to achieve a convenient hydrocarboxylation process (Table 3).]9a],[12] The hydroboration was conducted using either toluene or THF as the solvent, then the reaction mixture was transferred via cannula to a solution of KOtBu in THF at the appropriate temperature. Alternatively, the KOtBu could be added to the hydroboration mixture to achieve a one-pot process. Gratifyingly, the carboxylation was compatible with the hydroboration process and the overall yields for the two-step, one-pot reaction approached those observed for the one-step conversion of the isolated boronic ester to the carboxylic acid product.

Table 3.

One-pot hydroboration/carboxylation of styrenes.

|

1.2 equiv HBpin, 3.0 mol % CuCl, 3.0 mol % 1,2-diphenylphosphinobenzene, 6.0 mol % NaOtBu, THF.

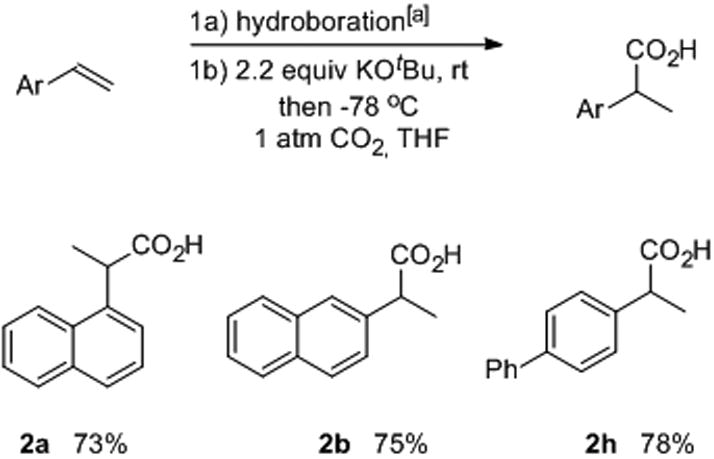

Other heterocumulenes, including isocyanates, isothiocyanates, and CS2, were suitable electrophiles for the reaction (Table 4). Conditions for the CO2 carboxylation could be extended to CS2 for the preparation of dithiocarboxylic acids in good isolated yields (entry 1). Reactions with isothiocyanates (entries 2-4) and isocyanates (entries 5-8) generally proceeded in high yields and did not require cooling the reaction to -78 °C prior to electrophile addition. Although isothiocyanates reacted smoothly with the 4-CO2Me substrate at -78 °C (entries 2-4, compounds 5c, 5f and 5i), isocyanates tended to competitively form oligomers, resulting in diminished yields (entries 5-8, compounds 6c, 6f, 6i and 6l). These functionalizations could also be accomplished in a single pot from the styrene precursors, as illustrated for the syntheses for 4b (entry 1), 5a (entry 2) and 6a (entry 5).

Table 4.

Other heterocumulene electrophiles.

|

Yield for the one-pot reaction using styrene as the substrate.

Reaction conducted at -78 °C.

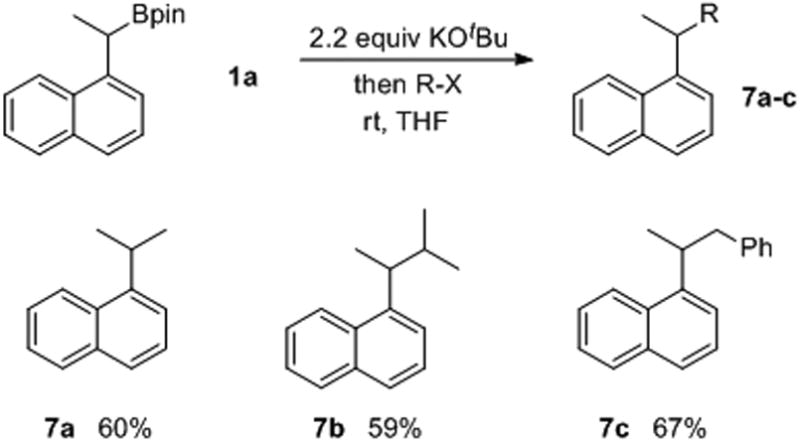

Finally, alkyl and benzyl halides were suitable electrophiles for benzylic functionalization (Table 5). MeI, iPrBr and BnBr, were all successfully coupled to 1a in yields of 60%, 59% and 67%, respectively. In the case of iPrBr (entry 2), this represented a convenient approach to the coupling of two secondary carbons at a benzylic position using an inexpensive Cu catalyst.

Table 5.

Alkyl halide electrophiles.[a]

|

NMR yield using 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane as an internal standard.

Other electrophiles, including aldehydes, ketones, ketenes and Bestmann's ylide (Ph3P=C=C=O), exhibited varying degrees of success in reactions with the anionic benzyl species generated from 1a.[13] The reaction of the benzyl anion with ketones and aldehydes did not result in exclusive addition to the carbonyl, but rather in significant competing formation of the enolate. Oligomerization was observed in all attempts to utilize ketenes or Bestmann's ylide as the electrophile.

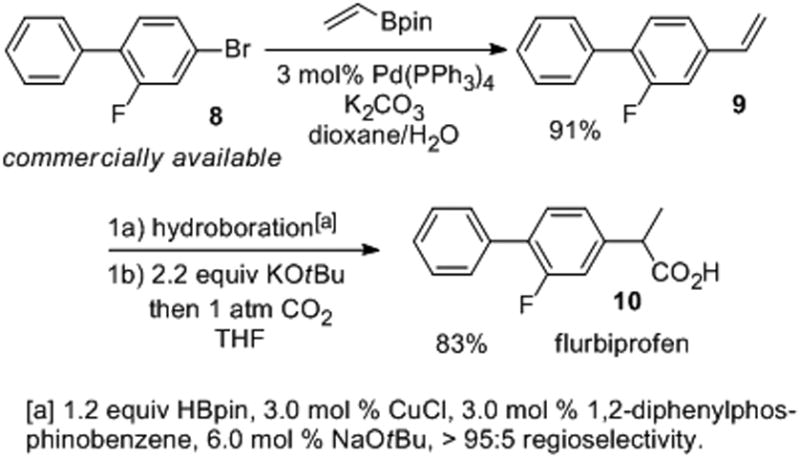

The utility of our methodology was demonstrated in a short synthesis of flurbiprofen (Scheme 1). This molecule is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) for the treatment of the inflammation and pain caused by osteroarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.[14] (R)-Flurbiprofen has been considered as a treatment for metastatic prostate cancer and analogues of this molecule have been explored for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.[15],[16] The commercially available 4-bromo-2-fluorobiphenyl was cross-coupled with a vinyl boronic ester to yield the olefin precursor for the key reaction in 91% yield. Our one-pot Cu-catalyzed hydroboration/carboxylation proceeded in 83% yield to provide flurbiprofen in a three-step, two-pot process from a commercially available starting material.

Scheme 1. A short synthesis of (+)-flurbiprofen.

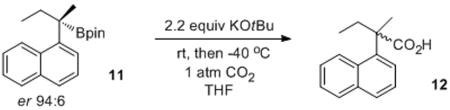

The apparent generation of a highly reactive benzylic carbanion using KOtBu as a relatively weak base was quite surprising. The presence of the boronic ester might lower the pKa of the benzylic proton sufficiently to allow direct deprotonation by KOtBu. However, the conversion of a tertiary boronic ester 1c to the corresponding carboxylic acid 2c (Table 1, entry 3) occurred in good yield. Additionally, when an enantioenriched tertiary boronic ester 11 was subjected to the reaction conditions, racemic 12 was obtained (eq 3), indicating significant cleavage of the C-B bond prior to electrophile attack. Additional evidence that the reaction proceeded through a benzyl carbanionic species were the improved yields obtained with substrates bearing electron-withdrawing groups on the aromatic ring. This suggested that stabilization of a benzyl anion was important to the success of the reaction.

|

(3) |

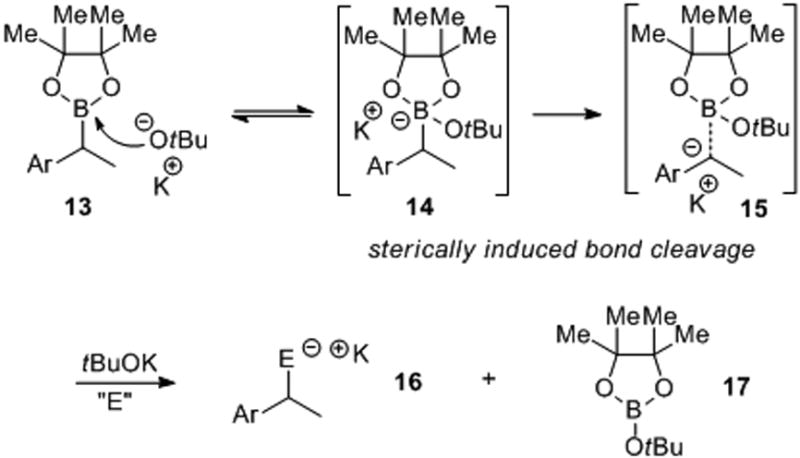

A proposed polar mechanism is illustrated in Scheme 2.[17] Reaction of the base with the boron of 13 yields the expected boronate complex 14. A sterically-induced cleavage of the C-B bond would give the presumed benzyl anion 15, which then reacts rapidly with the electrophile. The necessity of employing 2 equivalents of base is not clear; however, the formation of 17 may help to facilitate the reaction by driving the equilibrium in the desired direction.

Scheme 2. Potential polar mechanism for the sterically-induced bond cleavage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a convenient method for generating benzyl anions from styrenes has been demonstrated. This approach avoids the tedious and often capricious preparation of secondary and tertiary benzylic Grignards/organolithiums and exhibits greater functional group tolerance. The mild nature of the method allows for a one-pot transformation of styrene derivatives to a number of valuable motifs, including phenylacetic acids and amides. A three-step, two-pot synthesis of flurbiprofen from commerically available starting materials was accomplished in 76% overall yield, demonstrating the utility of the method. The chemoselective nature of the sterically-induced bond cleavage could also prove a powerful method for sequential transformations of molecules containing multiple C-B bonds obtained through well-precedented diborylations of olefins and allenes.[18] Future work is focused on the employing this method in diasteroselective tandem one-pot diborylation/functionalization reactions of olefins, dienes and allenes.

Experimental Section

General Procedure for the transition metal-free carboxylation of benzyl boronic esters

KOtBu (2.20 mmol, 2.2 equiv) and THF (8 mL) were loaded into a 100 mL Schlenk flask under an inert atmosphere. The flask was cooled to the desired temperature (rt, -45 °C, or -78 °C) before the boronic ester (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added via cannula or syringe as a solution in THF (2 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 10 min, then cooled to -78 °C. The flask was evacuated and backfilled with CO2 three times (CO2 was supplied using a Schlenk line). The flask was allowed to warm to room temperature under one atmosphere of CO2 and stirred for 3 h. The reaction was then quenched with 1 M HCl and extracted with several portions of dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and the volatiles removed under reduced pressure. The crude residue could be purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexanes/ethyl acetate gradient).

In some cases, the insolubility of the carboxylic acid in the organic phase necessitated the addition of several equivalents of methyl iodide prior to the aqueous quench. The corresponding methyl ester was then isolated by extraction and purified by column chromatography on silica gel.

Procedure for the one-pot hydrocarboxylation of styrenes via a Cu-catalyzed hydroboration/carboxylation

In the glovebox, a mixture of CuCl (0.03 equiv), bisdiphenylphosphinobenzene (0.033 equiv), and NaOtBu (0.03 equiv) was suspended in scrupulously dry toluene (0.33 M). The flask was tightly sealed and the mixture was removed from the glovebox and stirred for 10 min at rt. 4,4,5,5-Tetramethyl-[1,3,2]dioxaborolane (1.1 equiv) was added and the reaction mixture stirred for an additional 10 min. The desired styrene substrate (1 equiv) was introduced into the reaction as a solution in toluene via syringe. The reaction flask was placed in a pre-heated oil bath at 65 °C and left to stir overnight. The mixture was then diluted with THF to yield an overall solvent composition of 3:2 toluene: THF. A solution of KOtBu (2.2 equiv) in THF (0.22 M) was added and the reaction mixture stirred for 15 min. The flask was cooled to -78 °C, evacuated and backfilled with CO2 three times (CO2 was supplied through a Schlenk line). The mixture was warmed back to room temperature, stirred for 1 h, quenched with 1 M HCl and then extracted with several portions of dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and the volatiles removed under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexanes/ethyl acetate gradient).

General procedure for the preparation of dithiocarboxylic acids from benzyl boronic esters

KOtBu (2.20 mmol, 2.2 equiv) and THF (8 mL) were placed in a 100 mL Schlenk flask under an inert atmosphere. The flask was cooled to the appropriate temperature (rt, -45 °C, or -78 °C) before the boronic ester (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added via cannula or syringe in THF (2 mL). The solution was allowed to stir for 10 min. The flask was then cooled to -78 °C and the reaction mixture treated with CS2 (5.00 mmol, 5 equiv). The flask was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 1 h. The reaction was quenched with 5% NH4OH solution and extracted with one portion of diethyl ether. The aqueous phase was acidified with concentrated HCl and extracted with dichloromethane. The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and the volatiles removed under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (hexanes/ethyl acetate gradient).

General procedure for the reaction of isothiocyanates or isocyanates with benzyl boronic esters

KOtBu (2.20 mmol, 2.2 equiv) and THF (8 mL) were loaded into a 100 mL Schlenk flask under an inert atmosphere. The flask was cooled to the appropriate temperature (rt, -45 °C, or -78 °C) and the boronic ester (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added via cannula or syringe in THF (2 mL). The solution was allowed to stir for 10 min, then held at the temperature necessary to generate the reactive anionic intermediate. The isothiocyanate or isocyanate (1.10 mmol, 1.10 equiv) was then rapidly injected into the reaction mixture either neat or as a THF solution. The solution was stirred for 1 min prior to the addition of saturated NH4Cl (10 mL). The aqueous mixture was extracted with several portions of dichloromethane, the combined organic layers washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and the volatiles removed under reduced pressure. The crude residue was then purified by column chromatography on silica gel or was recrystallized from hexanes/ethyl acetate.

General Procedure for the reaction of alkyl halides with benzyl boronic esters

The boronic ester (0.4 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was dissolved in dry THF (4 mL) and treated with KOtBu (0.880 mmol, 2.2 equiv). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 10 min prior to injection of the alkyl halide (2.0 mmol, 5 equiv). The solution was stirred for 1 min before an aliquot of saturated aqueous NH4Cl was added to quench the reaction. The reaction mixture was extracted with portions of dichloromethane, the combined organic layers washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and filtered. The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography (hexanes/ethyl acetate gradient). The characterization data of the isolated products were consistent with reported characterization data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Charles Fry of the University of Wisconsin-Madison for assistance with NMR spectroscopy. Funding was provided by start-up funds from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The NMR facilities at UW-Madison are funded by the NSF (CHE-9208463, CHE-9629688) and the NIH (RR08389-01).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/or from the author.

References

- 1.Smith M, March J. Advanced Organic Chemistry. 6th. John Wiley Sons; New York: 2007. p. 1329. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For selected examples, see: Bernardon C. J Organomet Chem. 1989;367:11–17.Bernardon C, Deberly A. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1980;1:2631–2636.Bernardon C, Deberly A. J Org Chem. 1982;47:463–468.Screttas CG, Micha-Screttas M. J Org Chem. 1979;44:713–719.Benkeser RA, Siklosi MP, Mozden EC. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:2134–2139.Still WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:1481–1487.Parham WE, Jones LD, Sayed YA. J Org Chem. 1976;41:1184–1186.Gilman H, McNich HA. J Org Chem. 1961;26:3723–3729.

- 3.For selected examples, see: Betzemeier B, Knochel P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1997;36:2623–2624.Chia WL, Shiao MJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:2033–2034.Harada T, Kaneko T, Fujiwara T, Oku A. J Org Chem. 1997;62:8966–8967.Burkhardt ER, Rieke RD. J Org Chem. 1985;50:416–417.Kim SH, Rieke RD. J Org Chem. 1998;63:6766–6767. doi: 10.1021/jo9811367.

- 4.a) Clarembeau M, Krief A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:1093–1096. [Google Scholar]; b) Seyferth D, Suzuki R, Murphy CJ, Sabet CR. J Organomet Chem. 1964:431–433. [Google Scholar]; c) Kanda T, Kato S, Sugino T, Kambe N, Sonoda N. J Organomet Chem. 1994;473:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.For selected examples, see: Cohen T, Kreethadunrongdat T, Liu X, Kulkarni V. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3478–3483. doi: 10.1021/ja004353+.Screttas CG, Heropoulos GA, Micha-Screttas M, Steele BR, Catsoulacos DP. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:5633–5635.

- 6.For selected recent examples of C-C bond formation from boronic esters and related substrates, see: Bagutski V, Elford TG, Aggarwal VK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1080–1083. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006037.Ros A, Aggarwal VK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6289–6292. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901900.Thomas SP, French RM, Jheengut V, Aggarwal VK. Chem Rec. 2009;9:24–39. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20168.and references therein; Laroche-Gauthier R, Elford TG, Aggarwal VK. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16794–16797. doi: 10.1021/ja2077813.Chen A, Ren L, Crudden CM. J Org Chem. 1999;64:9704–9710.Crudden CM, Glasspoole BW, Lata CJ. Chem Commun. 2009:6704–6716. doi: 10.1039/b911537d.Matteson DS. Pure Appl Chem. 2003;75:1249–1253.

- 7.Federsel HJ. Nature Rev. 2005;4:685–697. doi: 10.1038/nrd1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For selected examples of sterically-induced bond cleavages, see: Fermin MC, Ho J, Stephan DW. Organometallics. 1995;14:4247–4256.Miyabo A, Kitagawa T, Takeuchi K. J Org Chem. 1993;58:2428–2435. doi: 10.1021/jo00079a039.Skagestad V, Tilset M. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:5077–5083.Carter P, Winstein S. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:2171–2175.

- 9.a) Noh D, Chea H, Ju J, Yun J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6062–6064. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Endo K, Hirokami M, Takeuchi K, Shibata T. Synlett. 2008:3231–3233. [Google Scholar]

- 10.For selected reviews, see: He LN, Wang JQ, Wang JL. Pure Appl Chem. 2009;81:2069–2080.Yin XL, Moss JR. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;181:27–59.Sakakura T, Choi TJC, Yasuda H. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2365–2387. doi: 10.1021/cr068357u.Aresta M, Dibenedetto A. Dalton Trans I. 2007;28:2975–2992. doi: 10.1039/b700658f.Bevy LP, editor. Progress in Catalysis Research. Nova Science Publishers; New York: 2005. Tolman WB, editor. Activation of Small Molecules. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: Germany: 2006. Marks TJ. Chem Rev. 2001;101:953996.Huang K, Sun C, Shi Z. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:2435–2452. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00129e.

- 11.For an example of deliberate deuterodeboronation of a benzyl boronic ester, see: Nave S, Sonawane RP, Elford TG, Aggarwal VK. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17096–17098. doi: 10.1021/ja1084207.

- 12.For an example of a direct hydrocarboxylation using a Ni catalyst and CO2, see: Williams CM, Johnson JB, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14936–14937. doi: 10.1021/ja8062925.

- 13.Organic Synthesis. 2005;82:140–146. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Drugs. 1979;18:417–438. doi: 10.2165/00003495-197918060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechter WJ, Leipold DD, Murray ED, Quiggle D, McCracken JD, Barrios RS, Greenberg NM. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2203–2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Peretto I, Radaelli S, Parini C, Zandi M, Raveglia LF, Dondio G, Fontanella L, Misiano P, Bigogno C, Rizzi A, Riccardi B, Biscaioli M, Marchetti S, Puccini P, Catinella S, Rondelli I, Cenacchi V, Bolzoni PT, Caruso P, Villetti G, Facchinetti F, Giudice ED, Moretto N, Imbimbo BP. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5705–5720. doi: 10.1021/jm0502541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Geerts H. Drugs. 2007;10:121–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Doraiswamy PM, Xiong GL. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:1–10. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A mechanism involving a radical intermediate was briefly considered. However, the thermodynamics of radical-mediated carboxylation are very unfavorable and this mechanism would not be expected to be operable. Kim S. Adv Synth Catal. 2004;346:19–32.Otero MD, Batanero B, Barba F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:2171–2173.

- 18.For relevant reviews, see: Beletskaya I, Moberg C. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2320–2354. doi: 10.1021/cr050530j.Marder TB, Norman NC. Top Catal. 1998;5:63–73.Bonet A, Pubill-Ulldemolins C, Bo C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7158–7161. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101941.Lillo V, Fructos MR, Ramirez J. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:2614–2621. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601146.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.