Abstract

Objectives

The current study tested opposing predictions stemming from the failure and acting out theories of depression-delinquency covariation.

Methods

Participants included a nationwide longitudinal sample of adolescents (N = 3,604) ages 12 to 17. Competing models were tested using cohort-sequential latent growth curve modeling to determine whether depressive symptoms at age 12 (baseline) predicted concurrent and age-related changes in delinquent behavior, whether the opposite pattern was apparent (delinquency predicting depression), and whether initial levels of depression predict changes in delinquency significantly better than vice versa.

Results

Early depressive symptoms predicted age-related changes in delinquent behavior significantly better than early delinquency predicted changes in depressive symptoms. In addition, the impact of gender on age-related changes in delinquent symptoms was mediated by gender differences in depressive symptom changes, indicating that depressive symptoms are a particularly salient risk factor for delinquent behavior in girls.

Conclusion

Early depressive symptoms represent a significant risk factor for later delinquent behavior – especially for girls – and appear to be a better predictor of later delinquency than early delinquency is of later depression. These findings provide support for the acting out theory and contradict failure theory predictions.

Keywords: Adolescents, Depression, Delinquency, Acting Out Theory, Failure Theory

Depression and delinquent behavior/conduct problems are two of the most common mental health problems facing adolescents (Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). Identifying risk factors for these syndromes is imperative given their relative stability over time (Capaldi, 1992; Wareham & Dembo, 2007), and the host of unique and overlapping negative outcomes associated with them. For example, adolescents reporting symptoms of depression and/or delinquency are at increased risk for concurrent and future academic failure, substance use/abuse, victimization, and interpersonal problems, among others (e.g., Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2005; Schaeffer et al., 2006). In addition, research suggests that adolescents who experience co-occurring depressive symptoms and delinquent behavior experience significantly worse overall outcomes relative to adolescents reporting only depressive or delinquent symptoms (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999).

Across longitudinal and cross-sectional studies of depression and delinquency in adolescents, two general trends are apparent: Both syndromes feature gender differences in prevalence and patterns of symptom change over time, and both co-occur with the other significantly more often than would be expected by chance (Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). In general, adolescent girls experience lower levels of delinquent behavior and higher levels of depressive symptoms relative to boys. Specifically, boys tend to exhibit more delinquent behavior than girls during early adolescence (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001), with continuing gender differences in later adolescence often reported (Ritakallio, Kaltiala-Heino, Kivivuori, & Rimpelä, 2005; Robins & Price, 1991), with some exceptions (for review, see Measelle, Stice, & Hogansen, 2006). In contrast, prevalence rates of depressive symptoms and disorders are similar for boys and girls in preadolescence, with disproportionate increases in girls’ symptoms resulting in significant gender differences first appearing between ages 11 and 15 (Cole et al., 2002; Hankin et al., 1998) and continuing through early adulthood (Holsen, Kraft, & Vitterso, 2000). Most studies of gender differences in depression and/or delinquency, however, have compared symptoms/prevalence at discrete time points or tested separate models for boys and girls, allowing only isolated conclusions regarding gender differences in specific variables. In contrast, no study of adolescent depression and delinquency has examined the extent to which gender differences in one variable account for gender differences in the other variable. For example, increased depressive symptoms in girls may increase the likelihood that girls engage in delinquent behavior, thus decreasing the magnitude of gender differences in delinquent behavior (e.g., Loeber & Keenan, 1994).

In addition to gender differences in both variables, depression and delinquency symptoms covary and diagnoses co-occur significantly more often than would be expected by chance (Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). Specifically, more than 30% of adolescents meeting criteria for a depressive disorder also meet criteria for conduct disorder (CD), and over 50% of adolescents with CD also meet criteria for a depressive disorder (Greene et al., 2002). In addition, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are consistent in demonstrating that depressive and delinquency symptoms covary significantly, both at discrete time points and in their patterns of change over time (Beyers & Loeber, 2003; Measelle et al., 2006; Wiesner & Kim, 2006).

After ruling out methodological confounds and symptom overlap as potential explanations, Wolff and Ollendick (2006) outlined three potential reasons for this covariation: shared risk factors, the failure model, and the acting out model. Proponents of the shared risk model argue that co-occurrence is caused by nonspecific risk factors (e.g., parent-child conflict) that collectively lead to separate but associated problem behaviors (i.e., depressive and delinquency symptoms; Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). Support for this model comes from studies documenting covariation in symptom counts and patterns of change over time (Beyers & Loeber, 2003), combined with evidence that these symptom clusters are best described as separate entities rather than a single common factor (Measelle et al., 2006). Studies investigating suspected shared risk factors, however, have generally failed to identify environmental or socio-contextual influences that account for depression-delinquency covariation, or simultaneously predict both clusters of symptoms (Beyers & Loeber, 2003)1. In addition, recent research suggests that future studies may be unlikely to identify common risk factors, despite findings that environmental factors separately influence both syndromes in adolescents (Burt, 2009). Specifically, a recent, large-scale heritability study indicated that depression and delinquency share little to no environmental influences (Subbarao et al., 2008).

Although common risk factors appear unable to account for depression-delinquency covariation, the two symptom clusters share significant genetic influence (rg = .59; Subbarao et al., 2008). Genetic factors therefore account for approximately 35% of the relation between depressive and delinquency symptoms, but do not inform the temporal ordering of symptom presentation or the potential for using symptoms of one syndrome to predict future symptoms of the other. In contrast, the failure and acting out models predict that symptom emergence for one disorder precedes and is causally responsible for the later development of symptoms of the other disorder. The failure model proposes that early delinquent behavior results in negative interpersonal outcomes (e.g., rejection by caregivers and peers) that decrease the availability of social supports, leading to increased depressive symptoms. These depressive symptoms, in turn, are thought to increase the likelihood of future delinquent behavior (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Support for this model comes from several comorbidity studies documenting that disruptive behavior disorders are typically diagnosed prior to depressive disorders (for a review, see Wolff & Ollendick, 2006)2. In addition, longitudinal models have demonstrated that higher levels of early delinquency significantly predict higher levels of later depressive symptoms in some (Capaldi, 1992; Curran & Bollen, 2001; Feehan, McGee, & Williams, 1993) but not all studies (Beyers & Loeber, 2003; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999).

In contrast, the acting out model predicts that depressive symptoms (e.g., irritability) may be expressed behaviorally through heightened aggression and rule-breaking in home and school settings (Akse, Hale, Engels, Raaijmakers, & Meeus, 2007; Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). Over time, these behaviors can result in increased conflict with parents and peers and ultimately to engagement in serious delinquency. Support for the acting out model comes from longitudinal studies demonstrating that early or time-averaged depressive symptoms significantly predict later delinquent behavior (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Curran & Bollen, 2001), arrests (Capaldi, 1992), and changes in delinquent behavior over time (Beyers & Loeber, 2003). In addition, perhaps the most compelling evidence comes from a seminal study by Puig-Antich (1982), who found that antidepressant treatment eliminated CD symptoms in 85% of early adolescent boys with comorbid major depressive disorder (MDD) and CD. Qualitative follow-up of these boys revealed that conduct problems tended to return following recurrence of depressive episodes, and abate again when depressive symptoms were treated successfully.

To date, only one study has explicitly tested opposing predictions from the failure and acting out models of depression-delinquency covariation. Beyers and Loeber (2003) used hierarchical linear modeling with a community sample of boys ages 13 to 17 participating in the Pittsburgh Youth Study, and found that time-averaged levels of depressive symptoms predicted age-related changes in delinquency, whereas delinquent symptoms did not significantly predict age-related changes in depressive symptoms. These patterns were not accounted for by socio-contextual variables, and their results suggest that early depressive symptoms were a better predictor of later delinquent behavior than early delinquency was of later depressive symptoms. Despite the elegant study design and methodological improvements over previous studies, Beyers and Loeber (2003) were limited to a regional sample of boys and statistical methods that did not allow them to model age-related symptom changes simultaneously as predictors and indicators.

The current study addressed these limitations by employing a random, large-scale, nationwide, accelerated longitudinal (aka ‘cohort-sequential’) sample of adolescent boys and girls ages 12–17 (at the initial assessment) to test opposing predictions stemming from the acting out and failure theories of depression-delinquency covariation. Specifically, competing models were tested using cohort-sequential latent growth curve modeling (LGM) to determine whether depressive symptoms at age 12 (baseline) are predictive of concurrent and age-related changes in delinquent behavior, whether the opposite pattern is apparent (delinquency predicting depression), and whether initial levels of depression predict changes in delinquency significantly better than vice versa. The use of this SEM-based approach has the additional advantage of explicitly controlling for measurement error, while allowing age-related symptom changes to simultaneously serve as predictors and indicators of other variables (Byrne, 2010). These methodological refinements also allowed us to examine gender differences in depression and delinquency symptoms, and use LGM-based mediation models to test the extent to which gender differences in baseline and age-related changes in delinquency were affected by gender differences in depression and vice versa (Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003).

We expected significant relations between depressive symptoms and delinquent behavior across all concurrent time points (e.g., Chen & Simons-Morton, 2009). In addition, we expected initial levels of depressive symptoms to predict age-related changes in delinquent behavior, but conflicting reports in the literature (e.g., Beyer & Loeber, 2003; Curran & Bollen, 2001) precluded hypotheses regarding the ability of early delinquency to predict age-related changes in depressive symptoms. Finally, no predictions were made regarding the impact of gender differences in depression on gender differences in delinquency (or vice versa).

Method

IRB approval was obtained prior to data collection. The 2005 National Survey of Adolescents-Replication was designed as a nationwide, random digit dial, standardized telephone interview of households with adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17, including an oversample of urban households. Sample selection and computer-assisted structured interviewing were conducted by Schulman, Ronca, and Bucuvalas, Inc. (SRBI), a survey research firm with extensive experience conducting sensitive interviews. A multistage, stratified, area probability, random digit dial six-stage procedure was used to construct the initial probability sample (see Kilpatrick et al., 2000). Once it was determined that a household had at least one youth in the targeted age range, screening and introductory interviews were conducted with parents to establish rapport. At each wave, verbal consent from a caregiver or legal guardian was obtained before interviewing the adolescents; all youth participants gave verbal assent. When possible, adolescents were interviewed immediately following parent interviews. If adolescents were unavailable or indicated that they could not answer questions freely, interviewers scheduled appointments and/or called back at different times of the day or days of the week. Adolescents were offered $10 to complete the structured interview. Supervisors conducted random checks of data entry accuracy and interviewers’ adherence to assessment procedures. During recruitment, 6,694 households were contacted that resulted in both a completed parent interview and identification of at least one eligible adolescent. Of these, 1,268 (18.9%) parents refused adolescent participation, 188 (2.8%) adolescents refused after their parents consented, 119 (1.8%) adolescent interviews were initiated but not completed, and 1,505 (22.5%) parent interviews were completed but the identified eligible adolescent was not available for interview at any of our callbacks. The remaining 3,614 cases resulted in completed parent and adolescent interviews. Ten cases were excluded due to age at initial interview, resulting in a wave 1 sample size of 3,604 adolescents ages 12–17. Participant demographics are highly similar to national population estimates, and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Cohort | N | Gender | Ethnicity

|

Wave 1 Annual Household Income

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Girls | % Caucasian | % African American | % Hispanic | % Native Amer./Alaskan | % Asian/Pacific Isl. | <$20K | $20K to $50K | > $50K | Not sure/Refused | ||

| 12 | 488 | 47.5% | 65.4% | 16.0% | 10.7% | 2.9% | 5.0% | 14.8% | 32.4% | 48.2% | 4.7% |

| 13 | 573 | 48.2% | 65.0% | 17.3% | 11.5% | 3.6% | 2.6% | 13.1% | 31.2% | 48.3% | 7.3% |

| 14 | 631 | 47.4% | 66.9% | 15.9% | 13.1% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 13.5% | 30.1% | 50.1% | 6.3% |

| 15 | 641 | 50.1% | 66.5% | 15.8% | 11.9% | 2.6% | 3.2% | 12.8% | 30.4% | 50.9% | 5.9% |

| 16 | 647 | 52.1% | 66.6% | 16.8% | 11.7% | 1.6% | 3.3% | 10.8% | 27.4% | 53.2% | 8.7% |

| 17 | 624 | 53.7% | 72.0% | 13.7% | 10.7% | 2.1% | 1.5% | 11.7% | 26.3% | 53.7% | 8.3% |

| Total | 3604 | 49.8% | 67.0% | 15.9% | 11.6% | 2.5% | 2.9% | 12.8% | 29.6% | 50.7% | 6.9% |

|

| |||||||||||

| National Estimates | -- | 48.7% | 60.6% | 15.2% | 17.3% | 3.3% | 3.6% | 12.9% | 27.8% | 59.3% | -- |

Note. Demographic variables were assessed using standard questions employed by the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1988). National estimates reflect U.S. Census estimates of the adolescent population in 2005. Age was measured as the current age in years at the time of the wave 1 interview (range = 12–17 years). No significant differences in gender, ethnicity, or income were found across cohorts (all chi-square p > .10). Amer. = American; Isl. = Islander

Waves 2 and 3 involved attempts approximately one year apart to recontact all adolescents included in the original survey. Methods for locating participants who had moved or changed phone numbers included asking about planned moves during the previous year’s interview, acquiring updated and previous contact information from directory assistance, and sending letters to last known addresses. Households with participants who were 18 years or older at follow-up did not include the parent/guardian portion of the interview. As expected based on the random digit dial method for participant selection, attrition across study waves was moderately high (33.5% between each wave). Two sets of analyses were undertaken to examine whether attrition was systematically related to any of the primary variables of interest. First, participants completing versus not completing all three waves were compared. Effect size confidence interval analysis revealed no differences for depressive symptoms or age (95% CIs include 0.0), and a small magnitude difference in delinquency symptom counts (Cohen’s d = −.15; 95% CI = −.10 to −.24), with study completers endorsing slightly fewer delinquent behaviors at wave 1 relative to non-completers. Second, 200 participants who could not be located at wave 2 were located and re-interviewed during wave 3. Effect size confidence interval analysis revealed no differences between this group and completers for age, depression, or delinquent behavior at this follow-up (all 95% CI contained 0.0). Collectively, these analyses suggest that the impact of missing data was minimal. In addition, the cohort-sequential design employed in the current study uses full information maximum likelihood estimation to include all participants and provides estimates based on multiple cohorts, which minimizes the impact of missing data at any individual wave (Byrne, 2010; Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2006). Thus, all 3,604 participants contributed data to at least one chronological age group regardless of their pattern of missing data, with a total of 7,500 data points each for the depression and delinquency variables described below (2,304 participants provided data for at least two waves of data collection, and 1,592 adolescents were available at all three waves). Nevertheless, we elected to describe the sample as “nationwide” rather than “nationally representative” to acknowledge the potential impact of participant refusal and attrition.

Measures

A structured telephone interview was used to collect information from participants. Variables selected for the current study included indices of delinquency and depressive symptoms. Interview questions for these variables administered in wave 1 were identical to those used in each follow-up wave. All questions had a yes/no response format.

Delinquent behavior

Past year delinquency was assessed with a modified version of the scale developed by Elliott, Huizinga, and Ageton (1985) for the National Youth Survey. Responses to nine items were summed (total score) to assess for the presence of serious delinquent behavior over the preceding year, including physical assault, selling drugs, burglary, motor vehicle theft, robbery, attacking someone with a weapon, attacking someone with intent to seriously hurt or kill, being arrested, or being sent to jail/juvenile detention.

Major depressive symptoms

Major depressive symptoms were assessed using the NSA Depression Module, a structured diagnostic interview that targets DSM-IV Major Depressive Episode criteria over the past year. Psychometric data support the internal consistency (Kilpatrick et al., 2003) and convergent validity (Boscarino et al., 2004) of the scale. Thirteen questions were used to assess each of the DSM-IV symptoms of depression over the preceding year, with thoughts of death and suicide separated into 2 items. The NSA wave 1 depression module probed for lifetime and past 6-month symptom occurrence, whereas past year and 6-month symptom occurrence were assessed at waves 2 and 3. To maintain a consistent metric across variables and study waves, past year depressive symptom endorsement at wave 1 was estimated based on past 6-month symptom endorsement at wave 1 by solving regression equations derived from predicting past year depressive symptoms from 6-month depressive symptoms at waves 2 and 3 (both R2 > .90).

Dependent variables

Total scores were calculated separately for delinquency and depressive symptoms at each of the 3 waves. Internal consistency was adequate across variables and study waves (αmean = .75; range = .65–.84). All variables were standardized (z-scores) to facilitate between- and within-model comparisons. Gender was coded as boys = 0, girls = 1. Additional socio-contextual variables were not included based on previous research indicating that depression and delinquency symptoms do not have significant shared environmental influences (Subbarao et al., 2008).

Data analysis

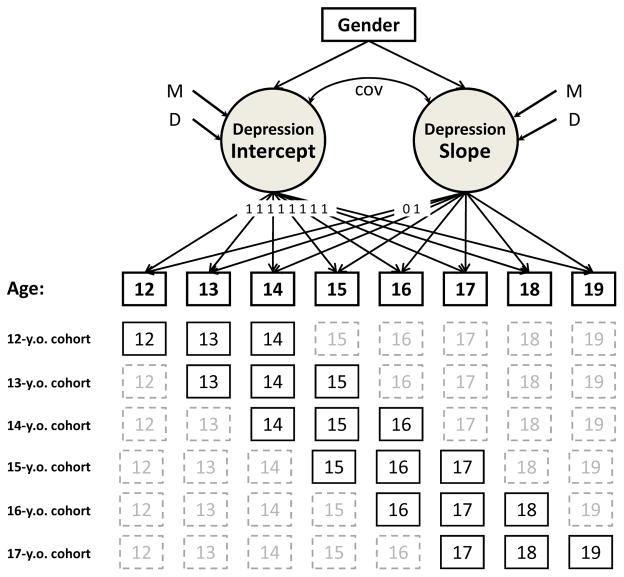

Cohort-sequential LGM was used to examine the interrelationships among initial (“baseline”) levels and age-related changes in symptoms of depression and delinquent behavior (Figure 1). Individuals were 12 to 17 years of age during the initial interview and were re-interviewed two additional times at approximately one year intervals, resulting in six temporally overlapping cohorts, each providing data for three adjacent ages (e.g., 12-year-old cohort, 13-year-old cohort …). The cohort-sequential design combines data across these cohorts to approximate a traditional longitudinal design of adolescents from ages 12 to 19, while minimizing potential cohort effects by estimating symptoms at each age based on multiple cohorts across different years (Duncan et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Cohort-sequential latent growth model for depression symptoms. Solid lines represent collected data, whereas dashed lines reflect data missing by design. Variables represent initial symptom levels at age 12 (intercept) and age-related increases from 12 to 19 (slope). An identical procedure was used to model delinquency symptoms. Cov = covariance; D = variance; M = mean; y.o. = year-old

LGM provides estimates of means and variances for two primary metrics: intercept and slope. Intercept means reflect the initial level of symptom endorsement (i.e., “baseline” at age 12), whereas slope means reflect the rate of change of these symptoms over time (Duncan et al., 2006). In contrast, significant variances in intercept and slope indicate individual differences in initial symptom level and rate of change over time, respectively, and support the analysis of potential predictors of these differences.

In LGM, regression weights for the intercept are all set to 1.0, which allows the intercept to be interpreted as the initial (“baseline”) level of a variable. For the slope factor, the first two regression weights (i.e., ages 12 and 13) are set to 0.0 and 1.0. Regression weights for all other ages are allowed to be estimated freely to capture both linear and nonlinear change over time, with the restriction that regression weights at each age are equal across cohorts3. The intercept and slope for each variable are set to covary, which is necessary for model specification (Duncan et al., 2006). Error variances and intercept-slope correlations were allowed to be freely estimated to improve model fit. Amos 18.0 structural equation modeling software was used for all analyses.

Four commonly used fit indices were used to estimate how well each model fit the data: chi-square, comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Nonsignificant chi-square values indicate perfect fit, but this index is heavily impacted by sample size. CFI and IFI values > .90 and RMSEA values < .05 indicate excellent fit (Kline, 2005).

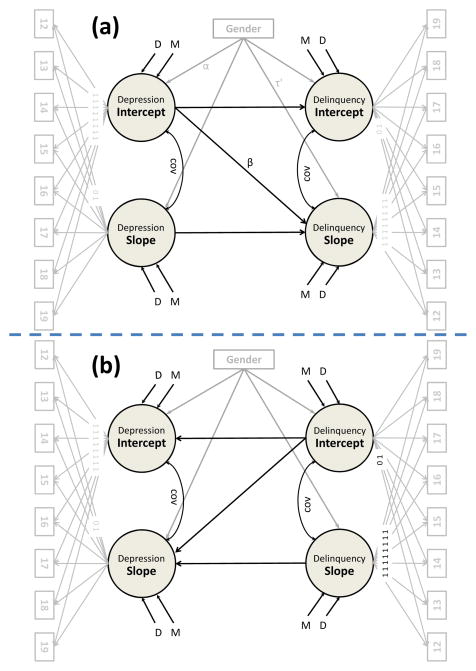

A three-tier data analytic approach was adopted to examine the study’s primary hypotheses. In the first tier (Figure 1), separate depression and delinquency models were created to examine initial levels (intercept) and age-related changes (slope) for these variables, and determine the need to examine potential predictors of these changes. In Tier II, the depression and delinquency models were combined, and two hypotheses were tested. In the first combined model (Figure 2a), initial levels of depressive symptoms were modeled to predict initial levels of delinquent behavior and age-related changes in delinquent behavior. In addition, age-related changes in depressive symptoms were modeled to predict age-related changes in delinquent behavior. In the second combined model (Figure 2b), these predictors were reversed: Initial levels of delinquent behavior were modeled to predict initial levels of depressive symptoms and age-related changes in depressive symptoms. In addition, age-related changes in delinquent behavior were modeled to predict age-related changes in depressive symptoms. For both models, mediation analysis for parallel process LGM was conducted to examine the extent to which gender differences in age-related changes (slope) in depression were mediated by delinquent behavior, and vice versa (Cheong et al., 2003). A final set of analyses (Tier III) used confidence interval analyses and comparison of non-nested model fit indices to determine whether one model fit the data significantly better than the other model, both in terms of relative model fit and the magnitude of prediction. Significance levels were set at p < .05 for all analyses; “trends” toward significance were not interpreted given the large sample size.

Figure 2.

Cohort-sequential latent growth models. Model (a) tests the acting out model, with depression intercept predicting delinquency intercept and slope, and depression slope predicting delinquency slope. Model (b) tests the failure model, with delinquency intercept predicting depression intercept and slope, and delinquency slope predicting depression slope. An example of the Tier II mediation analysis for parallel process latent growth modeling (Cheong et al., 2003) is shown in Model (a), which tests whether the direct impact of gender on age-related changes in delinquency (τ′) is mediated by gender’s impact on initial levels of depression (αβ).

Results

Tier I. Separate Depression and Delinquency Models

In Tier I, initial levels and age-related changes in depressive and delinquent symptoms were modeled separately. Data for these initial models are not shown in tables due to space limitations. Magnitude and significance levels are equivalent to those reported in the Tier II combined models unless noted otherwise. Both Tier I models fit the data significantly better when gender was allowed to predict intercept and slope (both chi-square difference tests p < .0005). With gender included, both the depression and delinquency models fit the data well (both models: CFI ≥ .96, IFI ≥ .96, RMSEA ≤ .02). Intercept and slope means were significant for both the depression and delinquency models (all p ≤ .003). For the depression model, slope and intercept were not correlated significantly (p = .07), indicating that initial levels of depression were not related significantly to age-related changes in depressive symptoms after accounting for gender. Delinquency slope and intercept were correlated significantly (r = .31; p = .04), indicating that adolescents endorsing initially higher levels of delinquent behavior showed steeper increases in delinquent behavior over time. Inspection of the slope means across models indicated that the quantity of depressive and delinquent symptoms increased with age (both p < .003). In addition, variances for intercept and slope were significant in both models (all p ≤ .02), indicating significant individual differences in initial levels and changes over time in both depression and delinquency symptoms, even after accounting for gender.

Inspection of the delinquency model indicated that gender significantly predicted initial levels of delinquency (β = −.06; p = .01), with boys endorsing higher levels of initial delinquency than girls. Changes in delinquency over time were not significantly different across genders (p = .052). In contrast, gender predicted changes in depressive symptoms (β = .20; p < .0005) but not initial levels of depression (p = .29), with girls increasing at significantly higher rates over time relative to boys.

Collectively, both the depression and delinquency models fit the data well and were characterized by gender differences and age-related symptom increases. In addition, both models retained significant individual differences in slope and intercept even after accounting for gender differences, indicating the need to examine potential predictors of these differences.

Tier II. Combined Predictive Models

Two separate models were constructed to examine the interrelationship between depressive and delinquent symptom endorsement, both initially and over time, and test whether (a) changes in delinquent behaviors are predicted by initial depression and/or changes in depression symptoms over time, or (b) changes in depression symptoms are predicted by initial delinquency and/or changes in delinquent behavior over time. For both models, model fit was significantly improved by including gender as a predictor (both chi-square difference tests p < .0005); therefore, only the full models (with gender included) are reported for parsimony. Regression weights for model specification and latent variable means/variances are shown in Tables 2 and 4, respectively. Regression weights for pathways explicitly testing failure and acting out model predictions are shown in Table 3 (left column: depression predicting delinquency; right column: delinquency predicting depression).

Table 2.

Age-related regression weights for combined models

| Depression predicting delinquency | Delinquency Predicting Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Depression Slope | Delinquency Slope | Depression Slope | Delinquency Slope | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

|

|

||||||||

| Age 12 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Age 13 | 1.00 | .31 | 1.00 | .42 | 1.00 | .36 | 1.00 | .39 |

| Age 14 | 2.31 (0.39) | .76 | 2.11 (0.21) | .72 | 2.23 (0.34) | .82 | 2.00 (0.20) | .63 |

| Age 15 | 2.54 (0.43) | .61 | 2.16 (0.22) | .61 | 2.48 (0.38) | .71 | 1.99 (0.21) | .51 |

| Age 16 | 2.75 (0.48) | .59 | 2.74 (0.30) | .73 | 2.65 (0.42) | .68 | 2.57 (0.29) | .63 |

| Age 17 | 3.35 (0.59) | .72 | 2.26 (0.27) | .68 | 3.24 (0.53) | .83 | 2.03 (0.26) | .52 |

| Age 18 | 2.85 (0.52) | .66 | 2.92 (0.36) | .73 | 2.91 (0.49) | .80 | 2.61 (0.33) | .59 |

| Age 19 | 2.79 (0.56) | .67 | 2.34 (0.36) | .67 | 2.96 (0.55) | .83 | 2.03 (0.34) | .53 |

Note. Unstandardized slope regression weights for ages 12 and 13 were fixed to 0.0 and 1.0, respectively, for both models. All non-fixed regression weights were significant at p < .0005. All unstandardized intercept regression weights (not shown) were set to 1.0. β-weights reflect standardized regression weights. Implied means are point estimates calculated based on the pattern of relationships specified by the model.

Table 4.

Combined model means and variances

| Depression predicting delinquency | Delinquency predicting depression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SE) | Variance (SE) | Mean (SE) | Variance (SE) | |

|

|

||||

| Depression intercept | −0.30 (0.03)*** | 0.24 (0.04)*** | −0.20 (0.04)*** | 0.22 (0.05)*** |

| Depression slope | 0.06 (0.02)** | 0.06 (0.03)* | −0.02 (0.03), ns | 0.07 (0.03)* |

| Delinquency intercept | −0.08 (0.04)* | 0.13 (0.03)*** | −0.17 (0.03)*** | 0.13 (0.02)*** |

| Delinquency slope | 0.17 (0.03)*** | 0.09 (0.03)*** | 0.14 (0.02)*** | 0.09 (0.02)*** |

Note. All means reflect z-scores

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Table 3.

Standardized regression weights for model predictions

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | Model comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model: Depression predicting delinquency | Model: Delinquency predicting Depression | |||||

| Depression intercept → | Delinquency intercept → | |||||

| Delinquency intercept | .39 (.22 to .55) | *** | Depression intercept | .42 (.27 to .57) | *** | Dep = Del |

| Delinquency slope | .30 (.15 to .45) | *** | Depression slope | −.20 (−.40 to .01) | ns | Dep > Del ** |

| Depression slope → | Delinquency slope → | |||||

| Delinquency slope | .30 (.15 to .45) | *** | Depression slope | .40 (.21 to .59) | *** | Dep = Del |

| Gender → | Gender → | |||||

| Depression intercept | .06 (−.04 to .16) | ns | Depression intercept | .11 (.01 to .21) | * | -- |

| Depression slope | .23 (.11 to .35) | *** | Depression slope | .21 (.10 to .32) | *** | -- |

| Delinquency intercept | −.14 (−.24 to −.04) | ** | Delinquency intercept | −.12 (−.22 to −.02) | * | -- |

| Delinquency slope | −.15 (−.23 to −.07) | *** | Delinquency slope | −.08 (−.15 to −.01) | * | -- |

| Covariances/Correlations | r | p | Covariances/Correlations | r | p | |

| Del intercept & slope | .31 | ns | Del intercept & slope | .62 | *** | -- |

| Dep intercept & slope | −.29 | ns | Dep intercept & slope | −.38 | ns | -- |

Note. Model comparison based on confidence interval (CI) analysis of standardized regression weight magnitudes (Tier III); Del = Delinquency predicting depression model, Dep = Depression predicting delinquency model.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Depression predicting delinquency

The model fit the data well (CFI = .93, IFI = .93, RMSEA = .02, 90% CIRMSEA = .019 to .024). As expected based on the Tier I models, intercept and slope means for both depression and delinquency were significant (Table 4, left column), and the correlation between initial depression and age-related changes in depressive symptoms was nonsignificant (Table 3, left column; p = .16). In addition, inspection of Table 3 (left column) indicates that the correlation between delinquency slope and intercept was not significant (p = .09), indicating that age-related changes in delinquent behavior were unrelated to initial delinquency levels after accounting for depressive symptoms. In contrast, initial levels of depression significantly predicted both initial delinquency (β = .39) and age-related changes in delinquency (β = .30). In addition, age-related changes in depression significantly predicted age-related changes in delinquency (β = .30). Collectively, these findings indicate that higher levels of depression at age 12 are predictive of age-related increases in delinquent behavior.

Gender significantly predicted age-related changes in depression and delinquency, with boys reporting greater increases in delinquency and girls reporting greater increases in depression with increasing age (Table 3, left column). Gender also predicted initial levels of delinquent behavior (boys higher), but did not predict initial levels of depressive symptoms (p = .26). Mediation analyses indicated that the impact of gender on age-related changes in delinquent symptoms was mediated by gender differences in age-related changes in depressive symptoms [αβ = .09; Sobel test (SE) = 2.67 (0.02), p = .008]. This indicates that the magnitude of delinquent behavior increases for boys relative to girls would be significantly greater if girls did not experience disproportionate increases in depressive symptoms over the same time period4. The impact of gender on delinquency intercept and slope was not mediated by initial levels of depression (both Sobel tests p = .28), as expected based on the nonsignificant relationship between gender and initial levels of depressive symptoms. Delinquency intercept and slope variances remained significant (Table 4, left column), indicating that significant individual differences in delinquent behavior endorsement remained after accounting for initial depressive symptoms, changes in depressive symptoms over time, and gender.

Delinquency predicting depression

The model fit the data well (CFI = .94, IFI = .94, RMSEA = .02, 90% CIRMSEA = .018 to .024). Inspection of Table 4 (right column) reveals that slope means were significant for delinquency but not depression (p = .37), whereas both the depression and delinquency intercepts were significant. In addition, Table 3 (right column) reveals that the correlation between delinquency slope and intercept was significant, whereas the correlation between depression slope and intercept was not (p = .12). These findings were consistent with the separate Tier I models, and indicated that initial delinquency endorsements were significantly associated with changes in delinquent behavior with increasing age, whereas changes in depressive symptoms were unrelated to initial levels of depression. Inspection of Table 3 (right column) reveals that initial levels of delinquency significantly predicted initial levels of depression (β = .42), and age-related changes in delinquency significantly predicted age-related changes in depression (β = .40). In contrast, initial levels of delinquent behavior did not predict age-related changes in depressive symptoms (p = .06). Collectively, these findings indicate that depression and delinquency are significantly associated with each other across ages, but that initial levels of delinquency do not predict age-related changes in depressive symptoms.

Gender significantly predicted age-related changes in depression and delinquency (Table 3, right column), with boys reporting greater increases in delinquency and girls reporting greater increases in depression. Gender also predicted initial levels of delinquent behavior and depressive symptoms. Mediation analyses indicated that gender exerted an indirect effect on initial depressive symptoms through its impact on initial delinquent behavior [αβ = −.05; Sobel test (SE) = −2.09 (0.03), p = .04). This indicates that the lack of significant gender differences in depressive symptoms at age 12 shown in Table 3 (left column) is at least partially due to boys’ higher levels of delinquent behavior at that time. Gender differences in age-related changes in depressive symptoms were not mediated by the delinquency intercept or slope (both Sobel tests p > .06). Inspection of Table 4 (right column) reveals that depression intercept and slope variances remained significant, indicating that individual differences in depressive symptom endorsement remained after accounting for initial delinquent symptoms, changes in delinquent symptoms over time, and gender.

Tier III: Model Comparison

Model comparison

Additional analyses were conducted to inform the interpretation of the results by determining whether one model fit the data significantly better than the other (‘depression predicting delinquency’ model vs. ‘delinquency predicting depression’ model). Two indices that can be used to compare non-nested models were examined: Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC), and the Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI), with smaller values indicating better fit (Byrne, 2010). AIC (496 vs. 504) and ECVI (.14, 90% CIECVI = .13 to .16 versus .14, 90% CIECVI = .13 to .15) values were approximately equivalent across models, suggesting that both models adequately fit the data, with neither model demonstrating clear superiority. Interpretations were therefore based on the findings of both models.

Magnitude of prediction

Standardized regression weights were subsequently compared using confidence interval analysis to examine the relative strength of prediction across models (‘depression predicting delinquency’ model vs. ‘delinquency predicting depression’ model). Differences in regression weights are significant at p < .01 if their 95% confidence intervals do not overlap, and significant at p < .05 if the proportion of confidence interval overlap is approximately .50 or less (Cumming & Finch, 2005). Three comparisons were made across the models presented in Table 3: intercept predicting intercept (.39 vs. .42), intercept predicting slope (.30 vs. −.20), and slope predicting slope (.30 vs. .40). Results are shown in the rightmost column of Table 3 and indicate that the depression intercept predicted the delinquency intercept as well as the delinquency intercept predicted the depression intercept (p > .05). In addition, the depression slope predicted the delinquency slope equally as well as vice versa (p > .05). In contrast, the depression intercept predicted the delinquency slope significantly better than the delinquency intercept predicted the depression slope as evidenced by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals. Collectively, these findings indicate that depression and delinquency are significantly associated with each other across ages. In addition, initial levels of depression predict age-related changes in delinquency significantly better than initial levels of delinquency predict age-related changes in depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The current study tested competing predictions stemming from the failure and acting out models of depression-delinquency covariation using accelerated longitudinal latent growth modeling with a random, nationwide sample of adolescents ages 12 to 19. Results indicated that depressive symptoms and delinquent behavior were related significantly, both initially and in their patterns of age-related change, and that depressive symptoms predicted concurrent delinquent behavior equally as well as vice versa. These findings are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Beyers & Loeber, 2003; Chen & Simons-Morton, 2009; Measelle et al., 2006; Wiesner & Kim, 2006), indicating that depression and delinquency symptoms are related significantly throughout adolescence, and extends previous findings by demonstrating that this relationship cannot be accounted for by gender differences in symptom prevalence or patterns of age-related change.

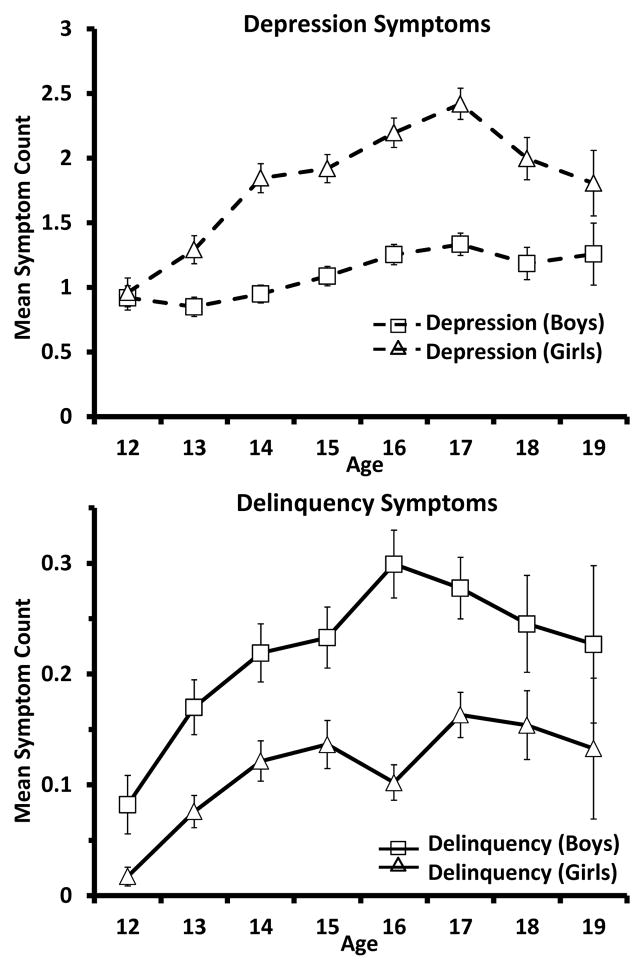

Examination of model-implied means across age groups (Figure 3) revealed that, in general, depression and delinquency symptoms both increased during early adolescence before decreasing in later adolescence. This pattern of age-related symptom change is consistent with previous longitudinal studies documenting overall increases in these symptoms during adolescence (Cohen et al., 1993; Duncan, Duncan, & Stryker, 2001), and studies documenting overall symptom decreases in samples of older adolescents (Beyers & Loeber, 2003), but inconsistent with findings of symptom stability over time (e.g., Wareham & Dembo, 2007). The discrepancy between these studies may be due to differences in their selection of within-subjects factors. Specifically, studies documenting symptom stability tend to collapse participants across age cohorts and examine changes over time (i.e., Time 1, Time 2 …), whereas studies reporting significant change tend to compare across age groups (i.e., Age 12, Age 13 …). Collapsing across age cohorts may mask depressive and delinquency symptom changes over time, given current and previous findings that these symptoms tend to increase and then decrease with age. In contrast, the cohort-sequential design used in the current study represents a compromise between these two methods, allowing examination of age-related changes while controlling for potential cohort effects (Byrne, 2010; Duncan et al., 2006).

Figure 3.

Depression (dotted lines) and delinquency (solid lines) symptom endorsements for boys (squares) and girls (triangles) across ages. Error bars reflect standard error (SE).

Failure and Acting Out Model Comparisons

Confidence interval analysis indicated that early depressive symptoms predicted age-related changes in serious delinquent behavior significantly better than early delinquency predicted age-related changes in depressive symptoms. This finding was robust to gender differences in initial symptom levels and age-related changes, and consistent with previous findings demonstrating the power of depressive symptoms for predicting changes in delinquent behavior among adolescent boys (Beyers & Loeber, 2003). Overall, the findings provide support for the acting out model and contradict failure model predictions that delinquent behavior predicts future depressive symptoms. We caution against interpreting these findings as support for masked depression, a once-popular but ultimately rejected theory suggesting that delinquent behavior reflects externalized symptoms of underlying depression (Carlson & Cantwell, 1980). In contrast, our data indicate that early depressive symptoms increase risk for the development of later delinquent behavior. This likely occurs through a developmental process whereby irritability associated with depression leads initially to heightened aggression and minor rule-breaking. Over time, those behaviors might negatively impact relationships with parents and prosocial peers, ultimately leading youth down a path of deviant peer association and involvement in serious delinquency. Future research is needed to identify whether the predictive power of early depressive symptoms is linear (i.e., more depressive symptoms predict more delinquent behavior), or whether a specific threshold of depressive symptoms can be identified, above which the risk of future delinquent behavior increases significantly.

Gender Differences

Gender differences in initial levels and age-related changes in delinquency (boys > girls), and age-related changes in depression (girls > boys), were apparent across models. In contrast, boys and girls demonstrated similar levels of initial depressive symptoms at age 12. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating higher prevalence of delinquent behavior in boys beginning in preadolescence and continuing throughout adolescence (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001; Ritakallio et al., 2005), as well as previous studies indicating that gender differences in depressive symptoms first appear in early adolescence as a result of a disproportionate increase in girls’ symptoms (Cole et al., 2002; Holsen et al., 2000). The current study extended these findings by demonstrating significant mediating influences of gender differences in depressive symptoms on delinquent behavior and vice versa (Cheong et al., 2003). Specifically, the lack of gender differences in initial depressive symptoms was at least partially accounted for by the higher levels of concurrent delinquent behavior reported by boys. In addition, the modest gender differences in age-related delinquent behavior increases would have been significantly greater in magnitude if girls did not experience disproportionate increases in depressive symptoms over the same time period. The latter findings may help explain why some studies have failed to find gender differences in adolescent delinquent behavior (see Measelle et al., 2006), and indicate that increases in depressive symptoms represent a particularly salient risk factor for increased delinquent behavior in girls (Loeber & Keenan, 1994; Wiesner & Kim, 2006).

Limitations

The current study employed a large, nationwide, random sample of boys and girls ages 12 to 19 across three study waves to test competing predictions stemming from the acting out and failure models of depression-delinquency covariation. The following limitations must be considered when interpreting the present results, however, despite these and other methodological refinements (e.g., controlling for measurement error and cohort effects, use of LGM mediation). First, the current study relied exclusively on structured adolescent self-report interviews, and our results may have differed to the extent that other informants or objective measures (e.g., arrest records) were used. Self-report studies, however, show similar rates of comorbidity relative to multiple informant/source studies of depression and delinquency (Wolff & Ollendick, 2006), and research indicates that adolescents may be more accurate reporters of depressive and delinquency symptoms than their parents and teachers (e.g., Cantwell, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1997). In addition, parent and adolescent reports of symptoms over time are highly correlated (rmed = .65), and self-reports appear to be more sensitive to early symptom emergence than parent reports (Cole et al., 2002). Finally, only approximately 10% of adolescents reporting engagement in delinquent behavior are ‘caught’, suggesting that self-reports are likely to result in higher estimates of delinquent behavior relative to parent reports and objective measures (e.g., police reports; Ritakallio et al., 2005).

A second limitation of the current study was the moderately high refusal and attrition rates, and the use of telephone survey methodology that excludes youth residing in households without landline telephone service. However, refusal rates were similar to or lower than those reported in other studies (Cole et al., 2002), and missing data analysis indicated that attrition was either unrelated or related weakly to our primary variables of interest. Further, the pattern of age-related symptom changes for boys and girls for both syndromes were highly consistent with extant literature (see Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). Nevertheless, it is impossible to know whether non-completers differed from completers during waves at which the former were not assessed. We therefore elected to refer to the sample as ‘nationwide’ rather than ‘nationally representative’ to acknowledge this limitation. Regarding telephone survey methodology, epidemiological data indicate that only 7.3% of U.S. children lived in households without a landline phone (i.e., households had only cellular service or no phone service) in the first half of 2005 (Blumberg & Luke, 2008), which was the year of initial study recruitment. It should be noted that this national percentage increased significantly over the study period, with 16.5% of children living in households without landlines by the second half of 2007 (Blumberg & Luke, 2008). Thus, although the exclusion of adolescents living in household without landlines has the potential to bias results, this issue was more prevalent during the latter part of the study, when it would have a greater influence on attrition (see discussion above) than study recruitment.

Third, the current study focused exclusively on severe delinquent behavior; the extent to which less severe oppositional behaviors would account for early and age-related changes in depressive symptoms is unknown. This distinction is important given that less severe oppositional and delinquent behaviors typically precede more severe delinquent behaviors (Rapport, LaFond, & Sivo, 2009). The current results, however, are highly consistent with those reported by Beyers and Loeber (2003), who examined both less and more severe conduct problems/delinquent behavior. Finally, the design of the current study precludes conclusions of causality, despite our finding that depressive symptoms predicted and temporally preceded age-related changes in delinquent behavior. Alternative explanations cannot be ruled out definitively – especially considering that significant individual differences remained across models.

Research and Clinical Implications

Collectively, results of the current study indicate that depressive symptoms represent a significant risk factor for age-related increases in delinquent behavior, especially for girls. Significant individual differences remained across models, however, even after accounting for gender differences and early delinquency and depression. Given that symptoms of the two disorders appear to share minimal to no significant environmental risk factors (Subbarao et al., 2008), future studies attempting to identify additional mechanisms accounting for depression-delinquency covariation might benefit from a focus on dispositional rather than situational factors. For example, simultaneous examination of the mediating influences of trait attitudes (Nebbitt & Lombe, 2008), personality factors (Akse et al., 2007), shared genetic influences (Subbarao et al., 2008), and symptoms of other disorders (Measelle et al., 2006) may provide improved explanation of depression-delinquency covariation, and result in the identification of additional risk factors associated with age-related increases in depression and delinquent behavior. Finally, residual individual differences may reflect the existence of identifiable subgroupings of each disorder that are differentially associated with each other (e.g., Harrington, Rutter, & Frombonne, 1996; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009). This argument is supported by recent studies identifying subgroups with distinct patterns of symptom change over time for both depressive and delinquent symptoms (Chen & Simons-Morton, 2009; Wiesner & Kim, 2006). Unfortunately, studies to date have generally failed to identify underlying factors responsible for these distinct trajectory groups, and significant individual differences remain after accounting for subgroup membership.

The current study provides support for the acting out model – early depressive symptoms predicted age-related changes in serious delinquent behavior significantly better than early delinquency predicted changes in depressive symptoms. In addition, increases in depressive symptoms over time appear to put adolescent girls at particular risk for engaging in severe delinquent behavior. Collectively, these findings indicate that depressive symptoms significantly increase the likelihood that adolescents will engage in delinquent behavior, and suggest that depressive symptom assessment should be a routine part of disruptive behavior evaluation and intervention. Although the current, community-based study did not examine treatment effects, the results allow us to echo the hypothesis put forth by Beyers and Loeber (2003) that treating depressive symptoms might serve as a protective factor against future delinquent behavior for adolescents with symptoms of both syndromes. To our knowledge, the aforementioned study by Puig-Antich (1982) is the only investigation that has examined this hypothesis in clinical research. Unfortunately, that study used a small sample (N = 13) and did not collect any long-term follow-up data. Thus, for youth with comorbid depression and delinquency, larger clinical studies examining the long-term effects of depression treatment on delinquent behavior represent an important next step in this line of research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01HD046830 (PI: Dean G. Kilpatrick). Views in this article do not necessarily represent those of NIH.

Footnotes

Studies examining more general constructs such as internalizing and externalizing behaviors, however, have identified common factors (e.g., lower SES, lower social competence, parent/family factors, stressful life events, delinquent peer affiliation; see Chen & Simons-Morton, 2009; Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1996). However, a consistent pattern of significant risk factors has not been identified across studies.

For an exception, see Kovacs, Paulauskas, Gatsonis, and Richards (1988), who reported that CD was diagnosed after MDD in a majority of cases.

Allowing these slope weights to be estimated freely resulted in significantly improved model fit relative to forcing a linear solution for all models tested (all chi-square difference test p < .0005).

This conclusion is based on comparing the positive indirect effect obtained via mediation analysis (αβ = .09) to the negative direct effect shown in the left column of Table 3 (τ’ = −.15) of gender on changes in delinquent behavior (gender: boys = 0, girls = 1).

Contributor Information

Michael J. Kofler, Department of Psychology, University of Central Florida

Michael R. McCart, Family Services Research Center, Medical University of South Carolina

Kristyn Zajac, Family Services Research Center, Medical University of South Carolina.

Kenneth J. Ruggiero, National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center, Medical University of South Carolina & Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center

Benjamin E. Saunders, National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center, Medical University of South Carolina

Dean G. Kilpatrick, National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center, Medical University of South Carolina

References

- Akse J, Hale B, Engels R, Raaijmakers Q, Meeus W. Co-occurrence of depression and delinquency in personality types. European Journal of Personality. 2007;21:235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Loeber R. Untangling developmental relations between depressed mood and delinquency in male adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:247–266. doi: 10.1023/a:1023225428957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Wireless substitution: Early release of estimates based on data from the National Health Interview Survey, July – December 2007. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/wireless200805.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Galea S, Adams RE, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D. Mental health service and medication use in New York after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: A meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:608–637. doi: 10.1037/a0015702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. 2. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:610–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at grade 8. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:125–144. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Cantwell DP. Unmasking masked depression in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:445–449. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Simons-Morton B. Concurrent changes in conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescents: A developmental person-centered approach. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:285–307. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:238–262. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, Velez CN, Hartmark C, Johnson J, et al. An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence: I. Age- and gender-specific prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1993;34:851–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Tram JM, Martin JM, Hoffman KB, Ruiz MD, Jacquez FM, et al. Individual differences in the emergence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescence: A longitudinal investigation of parent and child reports. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G, Finch S. Inference by eye: Confidence intervals and how to read pictures of data. American Psychologist. 2005;60:170–180. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bollen KA. The best of both worlds: Combining autoregressive and latent curve models. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA. Qualitative and quantitative shifts in adolescent problem behavior development: A cohort-sequential multivariate latent growth modeling approach. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An Introduction to Latent Variable Growth Curve Modeling. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot D, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug abuse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Feehan M, McGee R, Williams SM. Mental health disorders from age 15 to age 18 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:1118–1126. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: The consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:837–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Origins of comorbidity between conduct and affective disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:451–460. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199604000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RW, Biederman J, Zerwas S, Monuteaux M, Goring JC, Faraone SV. Psychiatric comorbidity, family dysfunction, and social impairment in referred youth with oppositional defiant disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1214–1224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R, Rutter M, Frombonne E. Developmental pathways in depression: Multiple meanings, antecedents, and endpoints. Developmental Psychopathology. 1996;8:601–616. [Google Scholar]

- Holsen I, Kraft P, Vitterso J. Stability in depressed mood in adolescence: Results from a 6-year longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best C, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Paulauskas S, Gatsonis C, Richards C. Depressive disorders in childhood: III. A longitudinal study of comorbidity with and risk for conduct disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;15:205–217. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Keenan K. Interaction between conduct disorder and its comorbid conditions: Effects of age and gender. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:497–523. [Google Scholar]

- Measelle JR, Stice E, Hogansen JM. Developmental trajectory of co-occurring depressive, eating, antisocial, and substance abuse problems in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:524–538. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebbitt VE, Lombe M. Assessing the moderating effects of depressive symptoms on antisocial behavior among urban youth in public housing. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2008;25:409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial Boys. Patterson, OR: Castalia Publishing; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J. Major depression and conduct disorder in prepuberty. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1982;21:118–128. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60910-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MD, LaFond SV, Sivo SA. Unidimensionality and developmental trajectory of aggressive behavior in clinically-referred boys: A Rasch analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ritakallio M, Kaltiala-Heino R, Kivivuori J, Rimpelä M. Brief report: Delinquent behavior and depression in middle adolescence: A Finnish community sample. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Price R. Adult disorders predicted by childhood conduct problems: Results from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area project. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes. 1991;54:116–132. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1991.11024540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo N, Masyn KE, Hubbard S, Poduska J, et al. A comparison of girls’ and boys’ aggressive-disruptive behavior trajectories across elementary school: Prediction to young adult outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:500–510. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: Irritable, headstrong, & hurtful behaviors have distinct predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:404–412. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao A, Rhee SH, Young SE, Ehringer MA, Corley RP, Hewitt JK. Common genetic and environmental influences on major depressive disorder and conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:433–444. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9189-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wareham J, Dembo R. A longitudinal study of psychological functioning among juvenile offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007;34:259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner M, Kim HK. Co-occurring delinquency and depressive symptoms of adolescent boys and girls: A dual-trajectory modeling approach. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1220–1235. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JC, Ollendick TH. The comorbidity of conduct problems and depression in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9:201–220. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.