Abstract

In healthy human pregnancies, placental growth factor (PGF) concentrations rise in maternal plasma during early gestation, peak over weeks 26–30, then decline. Since PGF in non-gravid subjects participates in protection against and recovery from cardiac pathologies, we asked if PGF contributes to pregnancy-induced maternal cardiovascular adaptations. Cardiovascular function and structure were evaluated in virgin, pregnant and postpartum C56BL/6-Pgf−/− (Pgf−/−) and C57BL/6-Pgf+/+ (B6) mice using plethysmography, ultrasound, qPCR and cardiac and renal histology. Pgf−/− females had higher systolic blood pressure in early and late pregnancy but an extended, abnormal midpregnancy interval of depressed systolic pressure. Pgf−/− cardiac output was lower than gestation day (gd)-matched B6 after mid-pregnancy. While Pgf−/− left ventricular mass was greater than B6, only B6 showed the expected gestational gain in left ventricular mass. Expression of vasoactive genes in the left ventricle differed at gd8 with elevated Nos expression in Pgf−/− but not at gd14. By gd16, Pgf−/− kidneys were hypertrophic and had glomerular pathology. This study documents for the first time that PGF is associated with the systemic maternal cardiovascular adaptations to pregnancy.

Keywords: Cardiac remodeling, Cardiovascular risk, Fetal growth, Placenta, Ultrasound

Introduction

Placental growth factor (PGF) is a member of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family [1] with important cardioprotective roles [2–4]. PGF has prominent, specific roles in cardiac stress and disease that have made it an attractive therapeutic candidate [2, 3]. Research into infarcted and pressure-loaded hearts identified the importance of PGF in adaptive hypertrophy and in promotion of angiogenesis; PGF deficits in the diseased heart are strongly correlated with diminished prognosis for repair and survival [2–4].

Pregnancy is physiologically challenging to the maternal cardiovascular (CV) system [5]. Typical pregnancy induces gains in blood volume [6] and cardiac output (CO), transient cardiac hypertrophy [6, 7] and vessel restructuring across the decidualized endometrium. Decidual vascular restructuring includes early neoangiogenesis and later spiral arterial remodeling [8], processes influenced by PGF [9, 10]. Plasma PGF concentrations fluctuate in women over pregnancy, increasing from 1st trimester, peaking at 26–30 weeks and declining towards term [1, 11]. We postulated that gestational elevations in PGF participate in the normal functional adaptions of the maternal heart to pregnancy.

PGF executes its angiogenic properties primarily through binding with high affinity to VEGFR1 (also known as FLT1) [1]. VEGFA also binds to this receptor but with lower affinity and can be displaced by PGF. Displacement of VEGFA increases its bioavailability and ability to drive the major pathway for angiogenesis though binding to VEGFR2 [9, 12]. Humans have four PGF isoforms [12, 13], whereas, mice express a single Pgf2 gene homologue [14]. Pgf−/− mice have been available for a number of years. Since Pgf−/− x Pgf−/− matings produce viable litters, containing normal numbers of pups [3, 9], PGF has generally been considered redundant during development [14]. To address whether PGF has a role in maternal cardiac adaptations to pregnancy, we quantified PGF in the plasma of normal mice over pregnancy. Since the time course for the pattern of detection resembled that of human pregnancy, we proceeded to compare the CV systems of C57BL/6-Pgf−/− (Pgf−/−) females mated by Pgf−/− males to C57BL/6-Pgf+/+ (B6) females mated by B6 males over pregnancy using plethysmography and ultrasound. These studies, supported by gross and histological studies of the maternal heart and kidney and by analysis of expression of targeted genes in the left ventricles (LV) of late gestational females, implicate the dynamic, gestational elevation of PGF in maternal plasma in maternal CV adaptations to pregnancy.

Methods

2.1 Experimental animals

B6-Pgf−/− mice were bred at Queen’s University from foundation stocks provided by P. Carmeliet [15]. Female and male B6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and used as controls. A total of 78 females (n=39/genotype) were used in this study. Animal usage was conducted in accordance with the SSR’s specific guidelines and standards and under protocols approved by the Queen’s University Animal Care Committee that were in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care’s Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

At 11–16 wk of age, females were paired with a male; detection of a copulation plug the following morning was considered gestation day (gd)0.

2.2 ELISA

PGF-2 concentrations were measured by Quantikine ELISA (R&D Systems; Cedarlane, Burlington ON) in undiluted, citrated plasma samples collected by cardiac puncture in anaesthetized virgin, gd-matched and 30 days postpartum (PP) Pgf−/− and B6, using n=3–5 females/genotype/time-point. Plasma samples were assessed as individual animals run in duplicate with means of the duplicates used for analyses. The assay was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3 Arterial pressure recordings

Due to cerebral vascular complications that included an incomplete circle of Willis [16], assessment of arterial pressure could not be conducted by radiotelemetry [17]. From a large study of Pgf−/− males and females on B6 and 129/SvJ strain backgrounds, only two 129/SvJ females were successfully recorded. These females mated and their gestational recordings are included as Supplemental Figure 1 to support data on the impact of PGF deficiency collected by plethysmography. Baseline tail cuff recordings of systolic pressure were obtained (Coda High Throughput 4 chamber, Kent Scientific Corp) from Pgf−/− (n=3) and B6 (n=4) females pre-trained to the instrument for 14d. Baseline pressure for each animal was averaged from 5–10 days of recordings after pre-training but prior to pregnancy. These females were subsequently mated and blood pressures were serially recorded on each day of pregnancy. Recordings included 25 cycles and machine acceptable measurements were subjected to outlier analyses and the remaining values were averaged for each animal for each day and normalized to baseline values for statistical analysis.

2.4 Ultrasonography

The Vevo770 high-frequency ultrasound system (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) was used to evaluate maternal CV function in anaesthetized virgin and pregnant (gds 8,10,12,14,16 and 18) Pgf−/− and B6 females (n=3–5dams/genotype studied at each time-point). Each female was studied on only one gd (i.e. not followed serially) to permit postmortem collection of tissues that could be directly related to the sonographic findings. Animals were anaesthetized using 5% inhaled isoflurane in oxygen and maintained at 1.5–2% during sonography. The Vevo707B 30MHz transducer was used for M-Mode cardiac scanning to obtain structural and physiological data. Parasternal long axis views of the heart were used with sample volume placed perpendicular to the aorta and through the left ventricle (LV) at a mid-papillary section to ensure consistency in measurement position between animals (Supplemental Figure 2). The Vevo704 40MHz transducer was used to perform renal, uterine and umbilical arterial scans. Pulsed-Wave (PW) Doppler measurements were obtained using an angle of insonation of less than 60° from uterine and renal arteries. Renal artery Resistance Index (RI) was calculated as RI = peak systolic velocity – end diastolic velocity/peak systolic velocity. Between gd10-18, as permitted by litter size and fetal development, 3–5 fetuses from each dam were located and fetal heart rates, umbilical artery peak velocities and umbilical artery RI were measured.

2.5 Postmortem organ wet-weights

Following ultrasonographic study, animals were euthanized by sodium pentobarbitol overdose (CEVA Sante Animale) (50mg/kg), exsanguinated by cardiac puncture and dissected. Hearts were removed and weighed intact. The heart chambers were then dissected, weighed individually and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for gene expression studies. Right hind limbs were dissected, digested overnight in 0.2M NaOH at 60°C and then tibia length was measured using digital calipers. Tibia lengths were constant during pregnancy and did not differ between genotypes (p=0.17) and, therefore, were used for normalization of heart weight to body size of each mouse. Both kidneys were freed of adhering adipose tissue and weighed. Fetal weights were obtained after removal of the amniotic sac, placenta and umbilical cord. Live pup weights were obtained on PP day 4, prior to euthanasia.

2.6 Histological and morphometric analyses

A separate cohort of virgin and gd16 Pgf−/− and B6 mice (n=3/genotype/time-point) was used exclusively for histological studies. These mice were euthanized and perfusion-fixed (transcardiac) with potassium-based perfusion buffer (140mM NaCl, 10mM KCl, 5mM EDTA) [18] for 5min (1mL/min.) followed by 4% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 5min (1mL/min) using a constant flow pump. Hearts and right kidneys were then removed, further fixed by overnight immersion in PFA, then processed for paraffin-embedding. Parasternal short axis cardiac (6 μm) and coronal renal sections (2 μm) were cut and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Sections were digitized and analyzed using standard light microscopy and Zeiss AxioVision Software. For each heart, maximum LV chamber area and exterior wall thickness were measured. For each kidney, 10 randomly selected renal corpuscles were identified and photographed. Surface areas of each corpuscle and glomerulus were measured. Subtraction of the latter was used to estimate Bowman’s space. Glomerular cellularity was estimated by counting endothelial cell numbers.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for NOS2 and NOS3 was performed on a second cohort of perfusion-fixed B6 and Pgf−/− hearts at virgin, gd8 and gd14. Paraffin-embedded hearts were cut at 6μm and a diaminobenzidine chromogen protocol was used. Slides were incubated with 3% bovine serum albumin buffer and antigen retrieval was performed using citrated buffer under humid conditions for 30min. Primary antibodies were purchased from ABCam (Rabbit polyclonal antibody against iNOS; 1:200 dilution) and Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Rabbit polyclonal antibody against eNOS; 1:100 dilution). Secondary antibody used for both was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Biotinylated goat anti-Rabbit IgG; 1:200 dilution). Sections were counterstained with Hematoxylin. Negative control consisted of an isotype control in place of primary antibodies; no staining resulted. Image analysis was performed by pixel quantification using image analysis software (GIMP 2.8.10).

2.7 Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from snap frozen LV samples from virgin, gd8 and gd14 females (previously used for ultrasound studies) using the high-pure tissue RNA isolation kit (Roche Scientific Co) and an established, modified protocol [19]. RT of total RNA was then performed using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) and manufacturer’s instructions. Relative mRNA expression was measured in triplicate and means reported relative to Gapdh mRNA using qPCR (Roche Lightcycler 480 II). Primers were designed using published GenBank sequences and Primer Designer Software version 2.01 (Scientific and Educational Software). Primer sequences and standard curve efficiencies are given in Supplemental Table 1.

2.8 Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5.0 Statistical Software (GraphPad). PGF ELISA analysis in detectable mice (B6 only) was performed using one-way ANOVA; differences between gd were determined by Tukey’s post-test. Comparisons between Pgf−/− and B6 genotypes across gestation were performed using two-way ANOVA and differences at specific gd were tested using Bonferroni’s post-test and data set-up as Pgf−/− vs B6. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SEM), using n=3–5 dams/group. Differences were defined as significant at p≤0.05. Regression analysis was used to determine differences in changes over time, with a significantly non-zero slope considered a change. Morphometric analysis between groups (virgin vs gd16) was performed using Student’s t-test.

Results

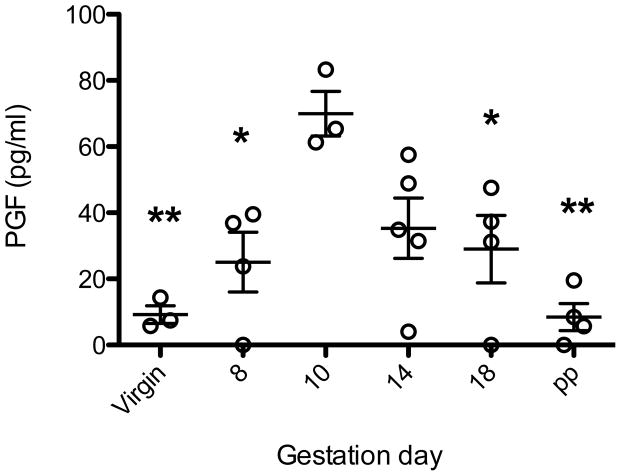

3.1 Maternal plasma PGF concentrations fluctuate over gestation

Plasma PGF levels were measured in virgin, pregnant and 30 days PP Pgf−/− and B6. PGF was not detected in any Pgf−/− sample. PGF levels in virgin and PP B6 were detectable but very low; significantly higher levels were detected in all pregnant B6 samples. PGF concentrations rose to gd 10-14 (statistically similar) then declined. PGF concentrations in B6 females were highest at gd10; this was the only time-point that showed a statistically significant increase from virgin levels. Gd10 levels were not significantly higher than levels at gd14; however, levels were higher than all other time points measured (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Circulating PGF concentrations in B6 mice using ELISA (n=3–5 pregnancies/time-point). PGF was below detectable levels in all Pgf−/− dams (not shown). PGF concentrations in B6 females peaked at gd10, the only time-point that showed a significant difference from virgin levels. Gd10 levels were not significantly higher than levels at gd14; but were higher than all other time points measured. Significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. * p≤0.05 from gd10, **p≤0.001 from gd10.

3.2 MAP over gestation

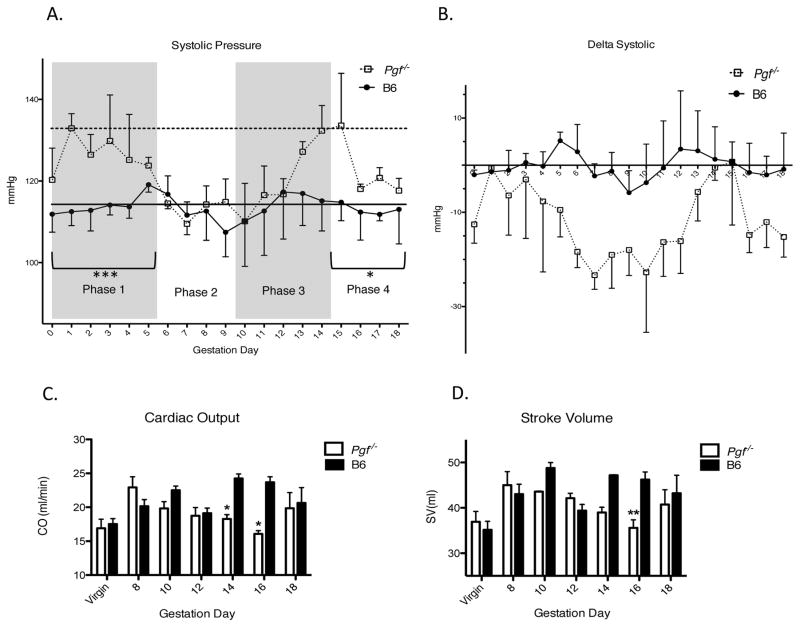

In virgin Pgf−/−, systolic arterial pressure (SAP) was elevated relative to B6 females (Figure 2A). This was also true in late gestation (Figure 2A). However, the overall pattern of change in Pgf−/− SAP was similar to B6. That is, SAP dropped from pre-conception baseline after gd6 with a gd9 nadir. B6 recovery to baseline pressure was achieved by gd12 but was delayed in Pgf−/−. Differences in SAP (delta from baseline) over pregnancy increased in a non-statistically significant manner in Pgf−/− compared to B6 dams (p=0.055; Figure 2B). When raw data were segregated into previously determined phases of embryonic and placental development thought to influence blood pressure [17], differences between groups were significant in Phase 1 (gd0-5, extent of the drop in SAP) and Phase 4 (gd15-18, extent of the rebound) (p=0.0002 and p=0.047, respectively). In both phases, Pgf−/− dams had higher SAP than B6 (Figure 2A). Duration of the hypotensive phase was longer in Pgf−/− dams than the single day nadir in B6 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Systolic arterial pressure (SAP) (A–B) was analyzed in trained Pgf−/− and control females across gestation using tail cuff plethysmography (n=4 B6, n=3 Pgf−/−). (A) Raw SAP over pregnancy was segregated into phases according to typical blood pressure fluctuations in normal mouse pregnancy (29). In phases 1 (gd0-5) and phase 4 (gd15-18), SAP was higher in Pgf−/− than B6 dams. Baseline (pre-pregnancy) values are indicated for Pgf−/− (horizontal dotted line) and B6 (horizontal solid line). Pre-pregnancy SAP was higher in Pgf−/− versus control females. (B) SAP was normalized to baseline values and represented as a change from baseline over pregnancy. Fluctuations in SAP in Pgf−/− dams appear to follow the same trends as B6 dams, however, magnitude of fluctuations appear more pronounced. The nadir appearing at gd9 in control mice appears to be prolonged to several days in Pgf−/− (A–B). PGF-related functional adaptations of the maternal heart. Maternal cardiac systolic function (B–C) was assessed using echocardiography (n=3–5/group/time-point). (C) Cardiac output (CO) increases over gestation in B6 dams but not Pgf−/− dams (by linear regression). PGF has an affect on CO in pregnancy, with decreased CO seen in Pgf−/− females, reaching significance at gd14 and gd16. (D) Stroke volume (SV) increases across gestation only in B6 dams (by linear regression). SV is lower overall in Pgf−/− females; differences at specific gds were reached at gd16. Changes over time were determined by linear regression with a statistically non-zero slope (C–D). Differences between groups were determined by Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test (A–D). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001 versus age-matched B6.

3.3 Echocardiographic evaluation of cardiac function

Echocardiographic analyses in virgin Pgf−/− and B6 mice showed no functional differences. In pregnant Pgf−/− females, cardiac output (CO) and stroke volume (SV) were stable while in pregnant B6 females CO and SV increased over gestation, as expected for a normal pregnancy (Figures 2C and 2D). CO was reduced overall in Pgf−/− dams across pregnancy compared with B6 (p=0.008); significance at specific time-points was found at gd14 and gd16 (Figure 2C). Overall SV during pregnancy was also smaller in Pgf−/− dams compared to B6 (p=0.005), reaching a specific time point statistical significance at gd16 (Figure 2D).

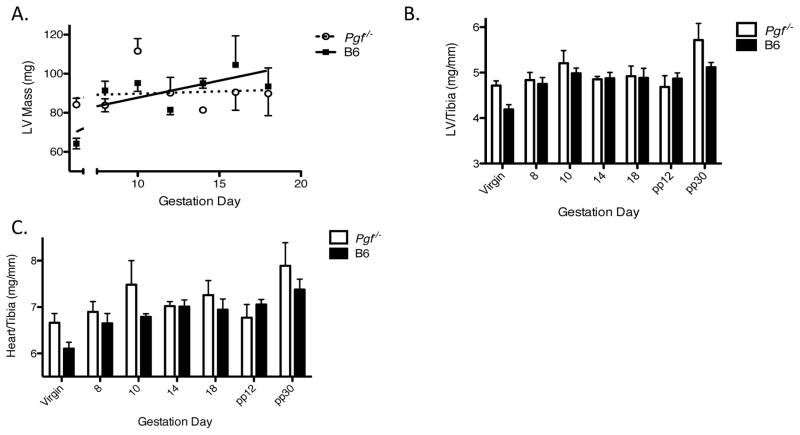

3.4 Echocardiographic and post-mortem assessment of cardiac structure

There were no statistical differences between Pgf−/− and B6 heart or LV weights for virgin animals (determined by echocardiography) (Figure 3A–C). Echocardiography did not detect any change in Pgf−/− LV mass over pregnancy while LV mass increased from virgin levels over gestation in B6 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

PGF deficiency is accompanied by cardiac structural differences across pregnancy and post-partum. (A) Left ventricular (LV) mass, determined by echocardiography (n=3–5/group/time-point), increased over gestation in B6 but not Pgf−/− dams. Total heart wet weight and chamber weights were determined at euthanasia (n=3–5/group/time-point) (B–C). Weights were normalized to tibia length (unchanged between groups; p=0.17) to account for differences in body weight initially and over the course of pregnancy (B–C). (B) Normalized LV mass appeared increased in Pgf−/− dams compared to controls across pregnancy and post-partum, the difference was not significant (p=0.088). (C) Normalized heart mass was greater in Pgf−/− versus B6 dams throughout pregnancy and post-partum (p=0.049) but the differences did not reach significance at any specific time-point. Changes over time were determined by linear regression with a statistically non-zero slope (A). Differences between groups were determined by Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test (B–C).

Post-mortem studies of hearts collected at each study time point supported the echocardiographic data. When normalized to tibia length, Pgf−/− LV wet-weight did not change over gestation while B6 LV wet-weight increased from its virgin level over gestation (Figure 3B). Overall differences in normalized LV mass throughout pregnancy and post-partum between Pgf−/− and B6 mice were not significant (p=0.088; Figure 2B). Normalized total heart weight increased over gestation and post-partum only in B6 (Figure 3C). Lack of PGF had an effect on total heart weight with Pgf−/− hearts being heavier than B6 over virgin, pregnancy and post-partum time-points (p=0.049); analysis of individual pregnancy time-points did not show statistical differences between genotypes (p=0.089) (Figure 3C).

Virgin Pgf−/− and virgin B6 LVs appeared structurally similar by routine histological examination (Supplemental Figure 3). Morphometric studies looking at wall width and chamber size at gd16 (when cardiac functional differences were seen sonographically) suggested that Pgf−/− LVs were not different from B6 (p=0.16; data not shown).

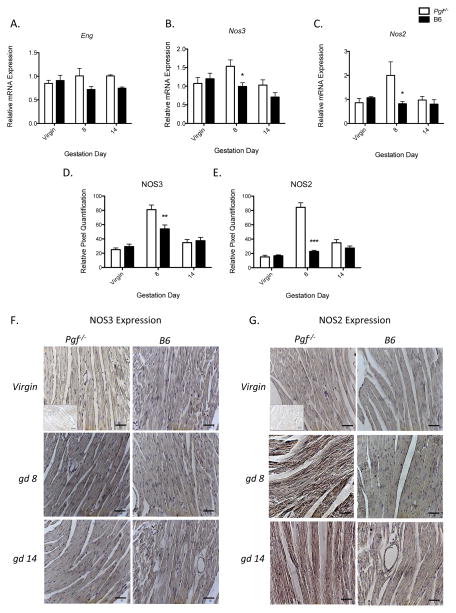

3.5 LV gene and protein expression

RT qPCR analysis for LV relative expression of the natriuretic peptide and VEGF gene systems (Nppa, Nppb, Npra, Nprc, Vegfa, Vegfb, Vegfr1, Vegfr2) found no differences between Pgf−/− versus B6 in virgin, gd8 or gd14 animals (data not shown). Relative Eng expression across all samples was greater in Pgf−/− LV versus B6 across gestation but did not reach significance at any specific time point studied (Figure 4A). Genotype had an effect on overall Nos3 relative expression, with greater expression in Pgf−/− LV. Time-point specific differences in Nos3 were present in gd8 but not virgin or gd14 Pgf−/− versus B6 LV (Figure 4B). PGF deficiency had a similar gestation day specific effect on relative Nos2 expression, being higher only in gd8 Pgf−/− LV. The effect of genotype on overall relative Nos3 expression showed a statistically non-significant increase in Pgf−/− LV (p-0.09; Figure 4C). These dynamic expression patterns were confirmed using IHC (Figure 4D–G).

Figure 4.

Upregulated gene expression in left ventricular (LV) tissue of Pgf−/− mice at midgestation. mRNA expression was determined using qPCR and normalized to expression of Gapdh (n=4/group/time-point) (A–C). Differences in LV NOS2 and NOS3 protein levels were measured by IHC (D–G). (A) Relative endoglin (Eng) expression was increased overall compared to B6 controls (p=0.039) but did not reach significance at any specific time-point. (B) Relative Nos3 (eNOS) expression was increased in Pgf−/− LV compared to B6. Differences at specific time points were significant at gd8. (C) Relative LV Nos2 (iNOS) expression was increased in Pgf−/− compared to B6 only at gd8. (D) NOS3 protein expression showed a non-statistically significant increase in Pgf−/− LV compared to B6 overall (p=0.09); gestation-day specific differences reached significance at gd8 (p<0.01). (E) NOS2 protein expression was also increased in Pgf−/− LV tissue versus B6 control both overall (p<0.0001) and at gd8 (p<0.001). (F–G) Representative micrographs from virgin, gd8 and gd14 Pgf−/− and B6 LV showing IHC staining for NOS3 and NOS2 with hematoxylin counter-stain. Quantitative differences in IHC staining were determined by relative pixel density. Inlets represent negative isotype control (F–G). Differences between groups determined by Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test (A–C). *P≤0.05. **P≤0.01, ***P<0.001. Scale bars represent 20μm.

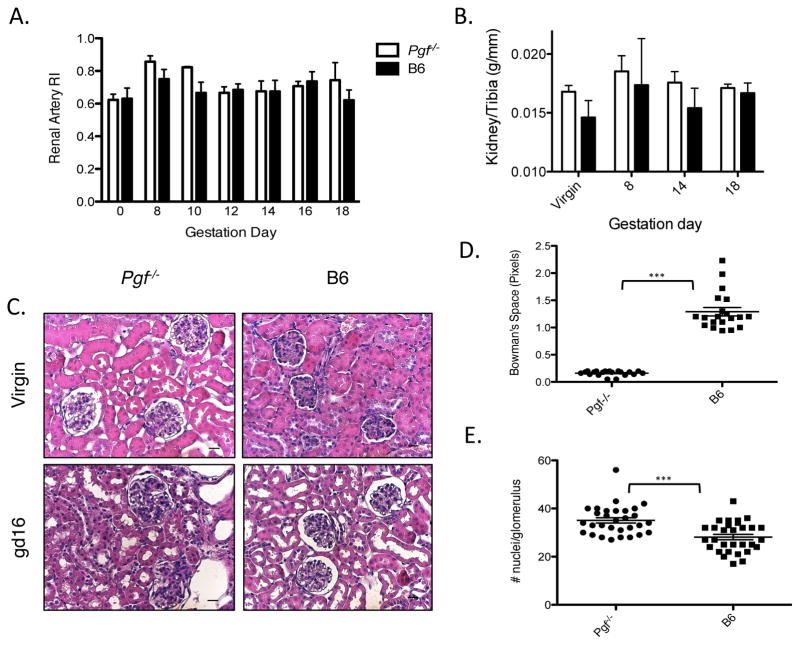

3.4 Renal analyses in virgin and pregnant Pgf−/− mice

Renal artery RI, used to measure downstream vascular impedance, did not differ between virgin Pgf−/− versus B6. Gestational renal artery RI in Pgf−/− was also not statistically different versus B6 (p=0.11; Figure 5A). Postmortem kidney weights normalized to tibia lengths were greater in Pgf−/− than in pregnancy status-matched B6 (p=0.036; Figure 5B). Renal histopathology (Figure 5C) at gd16 quantified glomerular hypercellularity and depleted urinary spaces in Pgf−/− versus B6 kidneys (p<0.001; Figure 5D–5E).

Figure 5.

Renal hypertrophy and structural abnormalities are present in pregnancies lacking PGF. (A) Renal artery RI in Pgf−/− versus B6 did not reach a statistically significant difference (n=3–5/group/time-point, p=0.11). (B) Total kidney wet-weight was measured at euthanasia and normalized to tibia length (n=3–5/group/time-point). Kidney weight increased in Pgf−/− dams over pregnancy and post-partum compared to B6 controls (p=0.0015). Differences at specific gd reached significance by 30 days post-partum (pp30). (C) Representative sections from non-pregnant (NP) and gd16 Pgf−/− and B6 dams. (D) Bowman’s capsular space (urinary space) was measured in randomly selected cortical glomeruli by subtracting glomerular area from total corpuscle surface area (n=3/group/time-point). Urinary space was significantly decreased in Pgf−/− kidneys versus controls. (E) Cellularity was measured in 10 random glomeruli; cellularity was increased in gd16 Pgf−/− versus B6 kidneys. Scale bars=20μm (C). Differences between groups were determined by Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test (A–B). Differences in urinary space and glomerular cellularity at gd16 were determined by Student’s T-Test (D–E). ***P≤0.0001.

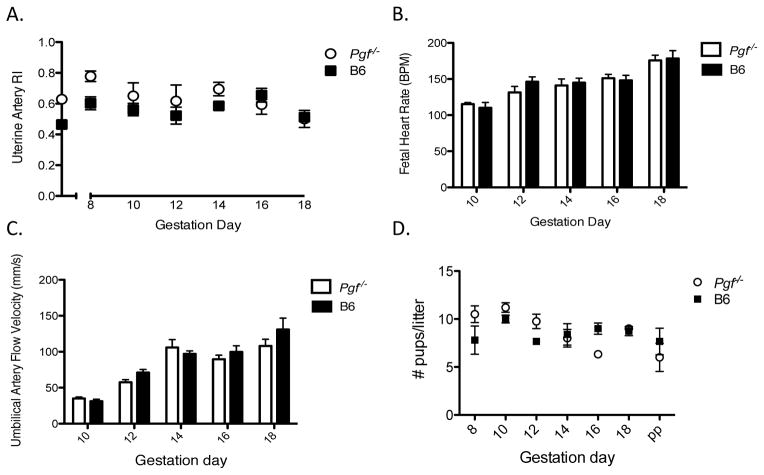

3.5 Fetal outcomes in Pgf−/− pregnancy

Uterine artery RI was elevated in Pgf−/− versus B6 dams across gestation (Figure 6A) but not at any specific gd. Fetal heart rates however did not differ between genotypes (Figure 6B). Umbilical artery RI was also similar between genotypes (Figure 6C) as were intrapartum and postpartum litter sizes (Figure 6D). Pgf−/− fetuses weighed less than B6 fetuses at both gd14 and gd18. This difference did not persist postpartum with pup weights measured as equivalent at PP day 4 (Table 1). These differences between groups in fetal and postnatal offspring weights were not associated with differences between genotypes in maternal body weight across pregnancy (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 6.

Maternal CV consequences of PGF deficiency have negligible fetal impact. High-frequency ultrasound was used for velocimetry of the uterine and umbilical arteries (n=3–5 dams/group/time-point; n=4 fetuses/dam) (A–C). (A) Uterine RI is increased in Pgf−/− dams compared to B6 across gestation (p=0.013) but did not reach significance at any specific gd. (B) Fetal heart rate was measured between peaks on PW Doppler cine loops of the umbilical artery. Fetal heart rate did not differ between genotypes at any gestational time-point measured. BPM= Beats per minute. (C) Umbilical artery RI did not differ between genotypes across gestation. (D) Litter size did not differ between Pgf−/− and B6 pregnancies. Differences between groups were assessed by Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test (A–D).

Table 1.

Fetal/pup weight in gestation and post-partum.

| Pgf−/− fetal/pup weight (g) | Pgf−/− (n) | B6 fetal/pup weight (g) | B6 (n) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gd14 | 0.206±0.006 | 16 | 0.27±0.004 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| gd18 | 0.976±0.034 | 12 | 1.217±0.049 | 12 | 0.0005 |

| PND4 | 3.095±0.196 | 22 | 3.324±0.146 | 19 | 0.37 |

n =3–4 dams per group

PND4 = Postnatal day 4

Discussion

This study provides the first thorough physiological assessment of the effect of PGF deficiency on mouse pregnancy. We postulated that the high PGF concentrations that develop in the plasma of pregnant women between early pregnancy and week 30 may contribute to the maternal CV adaptations necessary for support of conceptus growth and pregnancy success. Our comparisons between Pgf−/− and B6 pregnancies document an involvement of PGF in the normal cardiac adaptations that occur during mid to late pregnancy [20]. We found that by gd8 PGF concentrations in B6 maternal plasma were elevated over preconception values. Peak levels were found over gd10-14, after which PGF levels dropped and had returned to baseline at PP day 30. This pattern reflects the Pgf−/− gene expression time-course measured previously in decidua basalis [9] and is generally similar to that seen in human pregnancy. The pattern of mouse PGF fluctuation was coordinated with various maternal cardiac changes measured over normal B6 pregnancy. Cardiac functional parameters, such as CO and SV, peaked during mid-gestation (gd10-14). Similarly, structural parameters, such as LV mass, reached peak levels during mid-gestation.

In humans, maternal plasma PGF deficiency is linked to the hypertensive disorder preeclampsia (PE) and fetal growth restriction [21–23]. However, neither the effects of PGF on regulation of maternal blood pressure nor the roles of PGF in fetal development and growth are known. We evaluated both features in Pgf−/− mice that were confirmed by ELISA and PCR to be PGF deficient. Although radiotelemetric studies are regarded as the optimal approach for blood pressure studies in rodents [24] and were attempted, they could not be conducted in Pgf−/− mice due to cerebral vascular anomalies, including an incomplete circle of Willis in >80% of adult Pgf−/− females and males [16]. We therefore used plethysmography to assess the impact of PGF deficiency on gestational blood pressure. The key findings in Pgf−/− dams were that preconception SAP was higher, and that the pregnancy-induced drop in SAP (between gd6-9) was extended in length. Once Pgf−/− SAP returned to baseline (gd14), it differed from B6 by being unstable and dropping between gd16 and term. These measurements suggest an association of PGF with fine control of gestational blood pressure and with the normal, mid-gestational rebound in MAP [17, 25]. The normal mid-gestational ascent of MAP from nadir in normal mice occurs at the same time as completion of placental development, opening of the placental circulation and intraluminal invasion of trophoblasts [17, 26]. Differences in SAP were also present between gd0-5, with Pgf−/− dams having higher SAP than B6. A similar finding that PGF levels inversely correlate with maternal blood pressure was reported in a prospective study of 110 women in 1st trimester [27]. Both the mouse and human data attribute significance to the small elevations in plasma PGF that occur very early in pregnancy. SAP was elevated in Pgf−/− dams versus controls in late pregnancy (gd15-18). This phase immediately follows normal peak PGF levels in pregnancies. We postulate that differences in cardiac function between groups at gd14 and gd16, has systemic consequences that are reflected as changes in blood pressure by phase 4 of pregnancy. Baseline/pre-pregnancy SAP appeared higher in Pgf−/− females but did not reach statistical significance.

An important component of blood pressure regulation is the kidney. Both PGF and VEGF are linked to renal development and function and glomerular podocytes are known to express PGF [28]. Renal hypertrophy, glomerular hypercellularity and diminished urinary space were seen in Pgf−/− compared to B6 kidneys in late pregnancy. The elevated systolic pressures during early and late Pgf−/− pregnancy could either contribute to or result from the renal hypertrophy observed in pregnant Pgf−/− females.

Prior to conception, Pgf−/− hearts did not differ statistically from B6 hearts in any parameter measured. This supports previously published data that Pgf−/− mice, prior to any intervention, have no cardiac phenotype [29]. Increases in CO and SV characterize normal pregnancy in mice and women [30, 31]. These pregnancy-induced CV stressors bear similarities to other CV stressors, such as pressure overload or myocardial infarct [2, 3, 29, 32, 33]. In these latter conditions, PGF administration decreases heart failure incidence and ameliorates recovery by increasing cardiac angiogenesis and promoting adaptive hypertrophy. Gd16 Pgf−/− hearts phenotypically resembled pressure overload-hearts, being enlarged by weight but having a similar ventricular wall thickness than controls [2, 3, 29, 32–35]. The most pronounced cardiac differences between pregnant Pgf−/− and B6 dams were in CO and SV at gd14 and gd16, days following the highest circulating concentrations of PGF in normal pregnant mice. We suggest this reflects a delay in adaptation to PGF deficiency and indicates a role for PGF in maternal cardiac remodeling over mid pregnancy. Normalization of these parameters by gd18 in Pgf−/− dams corresponds with the decrease in circulating PGF levels of normal pregnancy and suggests a limited window for PGF activity during gestational CV adaptations. Dilatory growth is a possible explanation for the failure of CO and SV to increase across Pgf−/− gestations.

Cardiac stress alters expression levels of many genes [36, 37]. Members of the NOS gene system are prominent amongst the genes altered during cardiac stress and, like PGF, participate in cardioprotection, the hypertrophic response and angiogenesis [34, 36, 38, 39]. In mice, overexpression of Pgf increases LV Nos3 expression and NO production, steps pivotal to downstream cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [34]. Upregulation of Nos3 by pregnancy in Pgf−/− LV must be mediated via another, as yet undefined pathway. Both PGF and NOS3 increase adaptive hypertrophy in a cardioprotective manner; however, NOS3 (through NO) also has strong vasodilatory properties. This may contribute to the development of a more dilatory hypertrophy in the hearts of late gestational Pgf−/− dams. Much like NOS3, NOS2 has cardioprotective effects [40] and increased NOS2 levels are a downstream, compensatory effect of the increased systolic pressure in Pgf−/− early pregnancy [41]. Exaggerated fluctuations in blood pressure across pregnancy in Pgf−/− dams and their diminished ability to quickly rebound from the mid-gestation nadir may contribute to altered Nos2 expression. Nos2 and Nos3 expression in the heart appear to be inversely correlated with blood pressure in Pgf−/− dams at mid-gestation. The extended nadir in systolic pressure in Pgf−/− dams may result from the vasodilatory outcomes from increased Nos expression [42], however, this is yet to be addressed experimentally.

PGF deficiency and its associated maternal CV alterations were of limited impact on fetal blood flow and growth. Increased uterine artery RI in Pgf−/− dams indicated an increase in downstream vascular impedance [43]. PGF is known to contribute to uterine artery vasodilation, and these effects are pronounced in pregnancy [14]; in this way PGF contributes to uterine artery remodeling in response to pregnancy [44]. Spiral artery modification is only slightly delayed in pregnant Pgf−/− versus B6 females [9], suggesting that spiral arteries are not the cause of the impedance we observed. Intrapartum death was not elevated in Pgf−/− litters and fetuses had normal heart rates and umbilical flow velocities. However, late gestational Pgf−/− fetuses were lighter than controls, suggesting that PGF-driven angiogenesis may contribute directly to fetal growth rates, rather than through measurable circulatory parameters. Normalization of offspring weight by postnatal day 4 suggests acquisition of an additional CV risk factor, as rapid postnatal growth after slower than normal fetal growth is associated with subsequent CV and metabolic diseases [45–47]. Thus, while PGF appears redundant for fetal development, the high levels of PGF found in maternal plasma during normal pregnancy are associated with protective functions on the maternal CV system across mid gestation. The late pregnancy decline in maternal plasma PGF may reflect completion of the major steps of maternal cardiac and vascular remodeling needed to support the latest stages of pregnancy.

This study reveals novel associations between PGF levels and normal maternal CV adaptations to pregnancy. Continued efforts to stratify pregnant women who go on to develop pregnancy complications into those with low or with normal levels of PGF are warranted. This will enable refined evaluations of the exact role of PGF in the disturbed CV adaptations seen in pregnancy complications. Further evaluations may also shed light on the role of PGF in subsequent maternal CV risk after a complicated pregnancy [48].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from NSERC, CIHR, CFI and the Canada Research Chairs Program to BAC, and by training fellowships from CAPES’ Science without Borders Program (BZ, RL) and the R.S. McLaughlin Fellowship, Queen’s University (KLA). The work of PC is supported by the Belgian Science Policy (IAP #P7/03); Leducq Network of Excellence; the Belgian Science Fund (FWO) and long-term structural Methusalem funding by the Flemish Government.

The authors thank Ms. Tiziana Cotechini and Ms. Wilma Hopman for technical support and assistance in statistical analysis. We thank Ms. Carolina Venditti for instruction in plethysmography, Dr. Alastair Ferguson for provision equipment and Dr. David Armstrong for qPCR primer design. We appreciated the advice given by Dr. Iain Young on renal histological data. We also thank Mr. Matthew Rätsep, Ms. Ashley Martin, Ms. Vanessa Kay and Dr. Patricia Lima for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 2013 International Federation of Placenta Associations Meeting, September 11–14, Whistler, Canada

Declaration of Interest:

Peter Carmeliet holds patents on the use PGF as a cardioprotectant.

References

- 1.Vrachnis N, Kalampokas E, Sifakis S, Vitoratos N, Kalampokas T, Botsis D, Iliodromiti Z. Placental growth factor (PlGF): a key to optimizing fetal growth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:995–1002. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.766694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki H, Kawamoto A, Tjwa M, Horii M, Hayashi S, Oyamada A, Matsumoto T, Suehiro S, Carmeliet P, Asahara T. PlGF repairs myocardial ischemia through mechanisms of angiogenesis, cardioprotection and recruitment of myo-angiogenic competent marrow progenitors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carnevale D, Lembo G. Placental growth factor and cardiac inflammation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2012;22:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luttun A, Tjwa M, Carmeliet P. Placental growth factor (PlGF) and its receptor Flt-1 (VEGFR-1): novel therapeutic targets for angiogenic disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;979:80–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craici I, Wagner S, Garovic VD. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular risk: formal risk factor or failed stress test? Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;2:249–259. doi: 10.1177/1753944708094227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter S, Robson SC. Adaptation of the maternal heart in pregnancy. Br Heart J. 1992;68:540–543. doi: 10.1136/hrt.68.12.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsiaras S, Poppas A. Cardiac disease in pregnancy: value of echocardiography. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2010;12:250–256. doi: 10.1007/s11886-010-0106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris LK, Aplin JD. Vascular remodeling and extracellular matrix breakdown in the uterine spiral arteries during pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:28–34. doi: 10.1177/1933719107309588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tayade C, Hilchie D, He H, Fang Y, Moons L, Carmeliet P, Foster RA, Croy BA. Genetic deletion of placenta growth factor in mice alters uterine NK cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4267–4275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratsep MT, Carmeliet P, Adams MA, Croy BA. Impact of placental growth factor deficiency on early mouse implant site angiogenesis. Placenta. 2014;35:772–775. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welch PC, Amankwah KS, Miller P, McAsey ME, Torry DS. Correlations of placental perfusion and PlGF protein expression in early human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1625–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.012. discussion 1629–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Falco S. The discovery of placenta growth factor and its biological activity. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:1–9. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.1.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verlohren S, Stepan H, Dechend R. Angiogenic growth factors in the diagnosis and prediction of pre-eclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:43–52. doi: 10.1042/CS20110097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dewerchin M, Carmeliet P. PlGF: a multitasking cytokine with disease-restricted activity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012:2. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmeliet P, Moons L, Luttun A, Vincenti V, Compernolle V, De Mol M, Wu Y, Bono F, Devy L, Beck H, Scholz D, Acker T, et al. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med. 2001;7:575–583. doi: 10.1038/87904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratsep MT, Felker AM, Kay VR, Tolusso L, Hofmann AP, Croy BA. Uterine natural killer cells: supervisors of vasculature construction in early decidua basalis. Reproduction. 2015;149:R91–R102. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke SD, Barrette VF, Bianco J, Thorne JG, Yamada AT, Pang SC, Adams MA, Croy BA. Spiral arterial remodeling is not essential for normal blood pressure regulation in pregnant mice. Hypertension. 2010;55:729–737. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong DW, Tse MY, Wong PG, Ventura NM, Meens JA, Johri AM, Matangi MF, Pang SC. Gestational hypertension and the developmental origins of cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;391:201–209. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong PG, Armstrong DW, Tse MY, Brander EP, Pang SC. Sex-specific differences in natriuretic peptide and nitric oxide synthase expression in ANP gene-disrupted mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;374:125–135. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melchiorre K, Sharma R, Thilaganathan B. Cardiac structure and function in normal pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24:413–421. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328359826f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers RW, Roberts JM, Plymire DA, Pucci D, Datwyler SA, Laird DM, Sogin DC, Jeyabalan A, Hubel CA, Gandley RE. Low placental growth factor across pregnancy identifies a subset of women with preterm preeclampsia: type 1 versus type 2 preeclampsia? Hypertension. 2012;60:239–246. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.191213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alahakoon TI, Zhang W, Trudinger BJ, Lee VW. Discordant clinical presentations of preeclampsia and intrauterine fetal growth restriction with similar pro- and anti-angiogenic profiles. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:1854–1859. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.880882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molvarec A, Gullai N, Stenczer B, Fugedi G, Nagy B, Rigo J., Jr Comparison of placental growth factor and fetal flow Doppler ultrasonography to identify fetal adverse outcomes in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: an observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtz TW, Griffin KA, Bidani AK, Davisson RL, Hall JE. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 2: Blood pressure measurement in experimental animals: a statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association council on high blood pressure research. Hypertension. 2005;45:299–310. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150857.39919.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tejera E, Areias MJ, Rodrigues AI, Nieto-Villar JM, Rebelo I. Blood pressure and heart rate variability complexity analysis in pregnant women with hypertension. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2012;31:91–106. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2010.544801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann AP, Gerber SA, Croy BA. Uterine natural killer cells pace early development of mouse decidua basalis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:66–76. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasdaglis T, Aberdeen G, Turan O, Kopelman J, Atlas R, Jenkins C, Blitzer M, Harman C, Baschat AA. Placental growth factor in the first trimester: relationship with maternal factors and placental Doppler studies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:280–285. doi: 10.1002/uog.7548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tjwa M, Luttun A, Autiero M, Carmeliet P. VEGF and PlGF: two pleiotropic growth factors with distinct roles in development and homeostasis. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0776-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Accornero F, van Berlo JH, Benard MJ, Lorenz JN, Carmeliet P, Molkentin JD. Placental growth factor regulates cardiac adaptation and hypertrophy through a paracrine mechanism. Circ Res. 2011;109:272–280. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulandavelu S, Qu D, Adamson SL. Cardiovascular function in mice during normal pregnancy and in the absence of endothelial NO synthase. Hypertension. 2006;47:1175–1182. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000218440.71846.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savu O, Jurcut R, Giusca S, van Mieghem T, Gussi I, Popescu BA, Ginghina C, Rademakers F, Deprest J, Voigt JU. Morphological and functional adaptation of the maternal heart during pregnancy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:289–297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.970012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwama H, Uemura S, Naya N, Imagawa K, Takemoto Y, Asai O, Onoue K, Okayama S, Somekawa S, Kida Y, Takeda Y, Nakatani K, et al. Cardiac expression of placental growth factor predicts the improvement of chronic phase left ventricular function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1559–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gmeiner M, Zimpfer D, Holfeld J, Seebacher G, Abraham D, Grimm M, Aharinejad S. Improvement of cardiac function in the failing rat heart after transfer of skeletal myoblasts engineered to overexpress placental growth factor. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1238–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaba IM, Zhuang ZW, Li N, Jiang Y, Martin KA, Sinusas AJ, Papademetris X, Simons M, Sessa WC, Young LH, Tirziu D. NO triggers RGS4 degradation to coordinate angiogenesis and cardiomyocyte growth. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1718–1731. doi: 10.1172/JCI65112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gigante B, Morlino G, Gentile MT, Persico MG, De Falco S. Plgf−/−eNos−/− mice show defective angiogenesis associated with increased oxidative stress in response to tissue ischemia. FASEB J. 2006;20:970–972. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4481fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero M, Caniffi C, Bouchet G, Elesgaray R, Laughlin MM, Tomat A, Arranz C, Costa MA. Sex differences in the beneficial cardiac effects of chronic treatment with atrial natriuretic Peptide in spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong J, Chang C, Agrawal R, Walton GB, Chen C, Murthy A, Patterson AJ. Gene expression profiling: classification of mice with left ventricle systolic dysfunction using microarray analysis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:25–31. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b427e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones SP, Greer JJ, Kakkar AK, Ware PD, Turnage RH, Hicks M, van Haperen R, de Crom R, Kawashima S, Yokoyama M, Lefer DJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase overexpression attenuates myocardial reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H276–282. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00129.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manoury B, Montiel V, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide synthase in post-ischaemic remodelling: new pathways and mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:304–315. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo Y, Jones WK, Xuan YT, Tang XL, Bao W, Wu WJ, Han H, Laubach VE, Ping P, Yang Z, Qiu Y, Bolli R. The late phase of ischemic preconditioning is abrogated by targeted disruption of the inducible NO synthase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11507–11512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otani H. The role of nitric oxide in myocardial repair and remodeling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1913–1928. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer RM, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogueh O, Clough A, Hancock M, Johnson MR. A longitudinal study of the control of renal and uterine hemodynamic changes of pregnancy. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2011;30:243–259. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2010.484079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osol G, Celia G, Gokina N, Barron C, Chien E, Mandala M, Luksha L, Kublickiene K. Placental growth factor is a potent vasodilator of rat and human resistance arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1381–1387. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00922.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarry-Adkins JL, Martin-Gronert MS, Fernandez-Twinn DS, Hargreaves I, Alfaradhi MZ, Land JM, Aiken CE, Ozanne SE. Poor maternal nutrition followed by accelerated postnatal growth leads to alterations in DNA damage and repair, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and oxidative defense capacity in rat heart. FASEB J. 2013;27:379–390. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-218685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singhal A, Cole TJ, Fewtrell M, Deanfield J, Lucas A. Is slower early growth beneficial for long-term cardiovascular health? Circulation. 2004;109:1108–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118500.23649.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Winter PD, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Catch-up growth in childhood and death from coronary heart disease: longitudinal study. BMJ. 1999;318:427–431. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7181.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.