Abstract

Introduction The indirect laryngoscopy has an important role in the characterization of reflux laryngitis. Although many findings are nonspecific, some strongly suggest that the inflammation is the cause of reflux.

Objective The aim of this study was to evaluate the correlation between reflux symptoms and the findings of indirect laryngoscopy.

Methods We evaluated 27 patients with symptoms of pharyngolaryngeal reflux disease.

Results Laryngoscopy demonstrated in all patients the presence of hypertrophy of the posterior commissure and laryngeal edema. The most frequent symptoms were the presence of dry cough and foreign body sensation.

Conclusion There was a correlation between the findings at laryngoscopy and symptoms of reflux.

Keywords: laryngitis, laryngoscopy, gastroesophageal reflux

Introduction

The term laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (reflux laryngitis) was adopted in 2002 by the American Academy of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery and refers to clinical manifestations of gastric reflux on the upper airways.1 2 This supraesophageal form of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was named in 1994 by Koufman and Cummins,3 not with the intention to designate the origin of reflux, but to call attention to the predominance of symptoms and changes in the laryngopharyngeal segment.4

Estimates regarding the acid reflux causing posterior laryngitis vary widely, reaching up to 80% of cases, according to some authors.5 6 7 This causal relationship has been fed by the technological development of devices that are able to measure the acidity both on proximal and distal esophagus and the pharynx8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 and also the optical fibers, widely used in clinical practice, which greatly facilitate the visualization of the larynx.16 In this sense, indirect laryngoscopy has an important role in the characterization of the reflux laryngitis. Although many findings are nonspecific, some suggest that the etiology of the inflammation is the reflux, such as thickness, redness, and swelling concentrated in the posterior parts of the larynx (posterior laryngitis).

A symptom scale (Reflux Symptom Index [RSI]) was developed by Belafsky and collaborators to facilitate the suspect diagnosis and the clinical follow-up in pharyngolaryngitis. Patients score themselves on a scale from 0 to 5 of nine symptoms often described of the disease (Table 1).17 Values above 13 are considered abnormal.

Table 1. Reflux Symptom Index.

| During the last month, how did the following problems affect you? | 0 = No problem; 5 = Severe problem/very troublesome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoarseness or a problem with your voice | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Clearing your throat | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Excess throat mucus or postnasal drip | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Difficulty swallowing food, liquids, or pills | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Coughing after you ate or after lying down | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Breathing difficulties or choking episodes | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Troublesome or annoying cough | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Sensations of something sticking in your throat or a lump in your throat | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Heartburn, chest pain, indigestion, or stomach acid coming up | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Source: Belafsky et al.19

In the same way, they developed a scale related to the symptoms of reflux pharyngolaryngitis, Belafsky and collaborators created a score related to the findings of laryngoscopy (Reflux Finding Score [RFS]). It consists of scores from 0 to 4 determined by the examiner of eight laryngoscopic findings: subglottic edema, ventricular obliteration, erythema/hyperemia, vocal fold edema, diffuse laryngeal edema, posterior commissure hypertrophy, granuloma/granulation tissue, and thick endolaryngeal mucus (8 findings) (Table 2). The score, which ranges from 0 (normal) to 26 (worst possibility), indicates reflux pharyngolaryngitis if greater than 7.18 19

Table 2. Reflux Finding Score.

| Subglottic edema | Absent(0) Present (2) |

| Ventricular obliteration | Partial (2) Complete (4) |

| Erythema/hyperemia | Arytenoids only (2) Diffuse (4) |

| Vocal fold edema | Mild (1) Moderate (2) Severe (3) Polypoid (4) |

| Diffuse laryngeal edema | Mild (1) Moderate (2) Severe (3) Obstructing (4) |

| Posterior commissure hypertrophy | Mild (1) Moderate (2) Severe (3) Obstructing (4) |

| Granuloma/granulation tissue | Absent (0) Present (2) |

| Thick endolaryngeal mucus | Absent (0) Present (2) |

Source: Belafsky et al.17

The aim of this work is to analyze if there is a correlation between clinical symptoms of reflux pharyngolaryngitis (using the RSI) and the findings of indirect laryngoscopy (using the RFS) and thus detect the signs of indirect laryngoscopy that best correlate to the main symptoms of reflux laryngitis.

Materials and Methods

A survey was conducted of patients with symptoms of reflux pharyngolaryngitis at the Hospital Gaffree Guinle from August 2008 to December 2008. The following patients were excluded from the study: smokers; people with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or previous treatment with proton pump inhibitors, antacids, or H1 inhibitors; those with organic laryngeal disorders, previous radiotherapy, or head and neck surgeries; and psychiatric patients.20 The project was approved by the ethics committee on research (number 02/2008). All patients who agreed to participate provided informed and free consent.

We applied a symptom score (Table 1) developed by Belafsky to facilitate the clinical diagnosis and follow-up on DRFL (Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease). It is scored by the patient on a scale from 0 to 5 of nine symptoms often described in the disease. Values above 13 are considered abnormal. After this initial evaluation, patients had an indirect laryngoscopy exam. Belafsky and colleagues also created a score related to the findings of laryngoscopy (Table 2). The score, which ranges from 0 (normal) to 26 (worst possibility), indicates DRFL when greater than 7.19 The indirect laryngoscopy exam was performed with a rigid 70-degree fiber Karl Storz brand scope (Germany), always by the same examiner.

Results

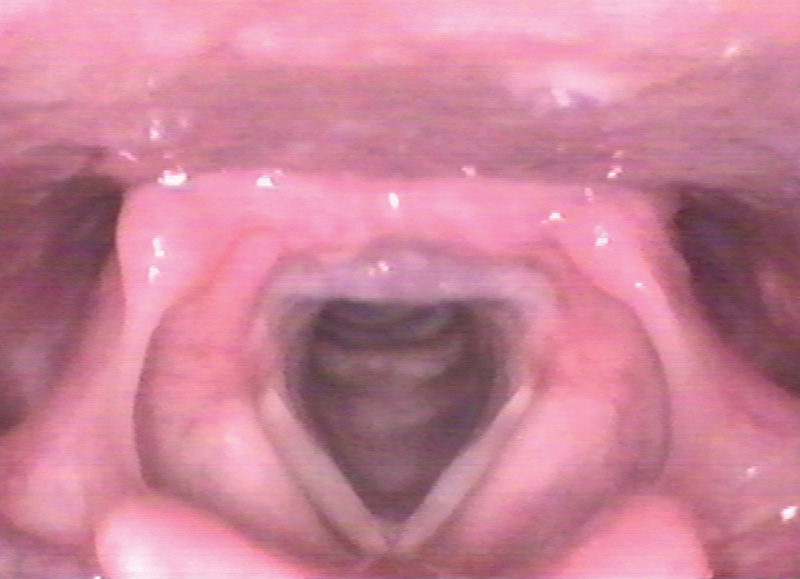

From the 405 patients with symptoms of reflux, 27 fulfilled the criteria of this survey. The average age of patients was 54.5 years, ranging between 19 and 81. The majority of patients were women (n = 22). The laryngoscopy results revealed that almost all patients had posterior commissure hypertrophy (n = 25; Fig. 1) and laryngeal diffuse edema (n = 21). The presence of laryngeal granuloma was not found. The average score of reflux symptoms was 17.9 (ranging from 3 to 34, standard deviation [SD] 8.82) and the findings regarding indirect laryngoscopy was 5.7 (ranging from 1 to 14, SD 3.82). The most frequently found symptom was the presence of dry cough episodes, foreign body sensation in the throat, and clearing the throat. The patients with clinical and laryngoscopic findings highly suggestive of DRFL received complementary therapy for the disease itself (antireflux therapy and suggestions for lifestyle changes).21

Fig. 1.

Presence of the posterior commissure hypertrophy.

The transversal study was used, and the criteria evaluated were mean age and sex, for symptoms of DRFL (RSI), and indirect laryngoscopy findings (RFS). The Pearson correlation coefficient for parametric variables was used to assess the degree of correlation, and to reject the null hypothesis, p ≤ 0.05 was used. The software used was SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science), IBM, United States, for evaluation v.14 for Windows XP, Microsoft, United States.

Analyzing the sum of symptoms of reflux (RFI) and correlating these findings to indirect laryngoscopy (RSI), a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.7 (strongly positive) was found, which was statistically significant (p ≤ 5). Correlating the main symptoms (episodes of dry cough, foreign body sensation in the throat, feeling of cleanliness, and roughness of throat) with the main findings on indirect laryngoscopy, a statistically significant correlation was found only between the variables hoarseness versus subglottic edema, hoarseness versus posterior commissure hypertrophy, and foreign body sensation versus posterior commissure hypertrophy (bold in the Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation between the symptoms and the findings on indirect laryngoscopy (statistically significant in bold).

| Subglottic edema | Ventricular obliteration | Erythema/ hyperemia | Posterior commissure hypertrophy | Thick endolaryngeal mucus | Granuloma or granulation tissue | Diffuse laryngeal edema | Vocal fold edema | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breathing difficulties or choking episodes | 0.192 | 0.323 | 0.158 | 0.237 | 0.273 | – | 0.235 | 0.322 |

| Hoarseness or a problem with your voice | 0.565 | 0.176 | 0.093 | 0.431 | 0.274 | – | 0.102 | 0.074 |

| Excess throat mucus or postnasal drip | 0.215 | –0.053 | 0.278 | 0.387 | 0.242 | – | –0.01 | 0.219 |

| Clearing your throat | 0.2 | –0.035 | 0.093 | 0.175 | –0.125 | – | 0.105 | 0.108 |

Discussion

One of the difficulties of the present study was to obtain a larger sample of patients, especially with the indiscriminate use of antireflux medications, culminating in incomplete and improper treatment of this disease. Another problem (or solution) was the exclusion of any patient who had used any tobacco in the years before the study, helping us select the “virgin” larynx, free from chronic inflammation.

The symptoms most frequently found were the presence of dry cough episodes, foreign body sensation in the throat, and throat clearing. No finding regarding indirect laryngoscopy had a strong positive correlation to this finding. However, the presence of foreign body sensation in the throat (globus pharyngeus) showed a positive correlation to the posterior third edema (posterior commissure), as well as the presence of dysphonia (hoarseness). This region of the larynx is anatomically more prone to chronic aggression, especially after the adoption of the supine position.

Some authors also reported dysphonia as a major symptom that is more common in the morning because of vocal cord edema caused by night reflux episodes, improving during the day.22 A weak positive correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient close to 0) was found between hoarseness and vocal fold edema, accepting the null correlation.

Laryngoscopy findings demonstrated that almost all patients had the presence of laryngeal edema associated with posterior commissure hypertrophy.

The diagnosis of reflux disease as the cause of pharyngolaryngitis is not simple. Despite the evidence that favors the association, there is no method that demonstrates unequivocally a causal relationship between Reflux and Laryngitis. In addition, endoscopy is less efficient in the diagnosis of DRFL, because these changes are found in fewer than 20% of patients with this disease. Vázquez de la Iglesia et al applied similar selection criteria and exclusion surveys and found a similar population (mostly women and patients with a mean age of 58.32),23 recommending a therapy test (empirical treatment) in patients with symptoms highly suggestive of DRFL (score greater than 13) and also suspicious laryngoscopic findings (score greater than 7), with proton pump inhibitors in full dose for 4 months. Correlating both scores, the researchers came to the conclusion that the laryngoscopic findings are most useful for diagnosis and patients' symptoms are most useful for follow-up and evolution of medical treatment.

Even after 60 years of research, both the diagnosis and treatment of GERD and extraesophageal reflux have been the target of several studies due to their controversial nature. The gold standard of pH monitoring on diagnosis has been questioned by some authors, who have stated that in addition to the test not having 100% sensitivity, the electrodes in the digestive tract interfere with the eating habits of the patients, which affects the results and consequently the diagnosis.24 Other studies must establish a consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with pharyngolaryngeal reflux disease to improve the quality of life in these patients.25

Conclusion

After analyzing the data presented, we conclude that there was a strong positive correlation between the findings of indirect laryngoscopy and symptoms of reflux among patients who participated in the study in question; the most common symptoms were episodes of dry cough, foreign body sensation in the throat, and throat clearing. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant correlation between the symptoms of hoarseness and foreign body sensation with the finding of posterior commissure hypertrophy in indirect laryngoscopy.

References

- 1.Koufman J A, Aviv J E, Casiano R R, Shaw G Y. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: position statement of the committee on speech, voice, and swallowing disorders of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127(1):32–35. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.125760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Liu X, Liu Y L. et al. Correlation of pepsin-measured laryngopharyngeal reflux disease with symptoms and signs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(6):765–771. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koufman J A Cummins M M The prevalence and spectrum of reflux in laryngology: a prospective study of 132 consecutive patients with laryngeal and voice disorders. 1994 Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/trj60d00. Accessed 8 September 2014

- 4.Eckley C A, Rios LdaS, Rizzo L V. Salivary egf concentration in adults with reflux chronic laryngitis before and after treatment: preliminary results. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73(2):156–160. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koufman J A The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury Laryngoscope 1991101(4 Pt 2, Suppl 53):1–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nostrant T T Gastroesophageal reflux and laryngitis: a skeptic's view Am J Med 2000108(4, Suppl 4a):149S–152S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckley C A, Costa H O. Comparative study of salivary pH and volume in adults with chronic laryngopharyngitis by gastroesophageal reflux disease before and after treatment. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;72(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30035-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz P O. Ambulatory esophageal and hypopharyngeal pH monitoring in patients with hoarseness. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85(1):38–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ulualp S O, Toohill R J, Hoffmann R, Shaker R. Pharyngeal pH monitoring in patients with posterior laryngitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120(5):672–677. doi: 10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a91774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeMeester T R, Johnson L F. The evaluation of objective measurements of gastroesophageal reflux and their contribution to patient management. Surg Clin North Am. 1976;56(1):39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)40834-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dent J, Dodds W J, Friedman R H. et al. Mechanism of gastroesophageal reflux in recumbent asymptomatic human subjects. J Clin Invest. 1980;65(2):256–267. doi: 10.1172/JCI109667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirschowitz B I. A critical analysis, with appropriate controls, of gastric acid and pepsin secretion in clinical esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;101(5):1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90062-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bumm R, Feussner H, Hölscher A H, Jörg K, Dittler H J, Siewert J R. Interaction of gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal motility. Evaluation by ambulatory 24-hour manometry and pH-metry. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37(8):1192–1199. doi: 10.1007/BF01296559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiorucci S, Santucci L, Chiucchiú S, Morelli A. Gastric acidity and gastroesophageal reflux patterns in patients with esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(3):855–861. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90017-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smit C F, Tan J, Mathus-Vliegen L M, MathusVliegen L M, Devriesse P P, Brandsen M, Grolman W, Schouwenburg P F. High incidence of gastropharyngeal and gastroesophageal reflux after total laryngectomy. Head Neck. 1998;20(7):619–622. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199810)20:7<619::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw G Y, Searl J P. Laryngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux before and after treatment with omeprazole. South Med J. 1997;90(11):1115–1122. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199711000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belafsky P C, Postma G N, Koufman J A. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS) Laryngoscope. 2001;111(8):1313–1317. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qadeer M A, Swoger J, Milstein C. et al. Correlation between symptoms and laryngeal signs in laryngopharyngeal reflux. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(11):1947–1952. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000176547.90094.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belafsky P C, Postma G N, Koufman J A. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI) J Voice. 2001;16(2):27–47. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(02)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Book D T, Rhee J S, Toohill R J, Smith T L. Perspectives in laryngopharyngeal reflux: an international survey. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(8 Pt 1):1399–1406. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford C N. Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. JAMA. 2005;294(12):1534–1540. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wendl B, Pfeiffer A, Pehl C, Schmidt T, Kaess H. Effect of decaffeination of coffee or tea on gastroesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8(3):283–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martins R HG. Manifestações otorrinolaringológicas relacionadas à doença do refluxo gastroesofágico. Um tema inesgotável!!! Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73(2):14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vázquez de la Iglesia F, Fernández González S, Gómez MdeL. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: correlation between symptoms and signs by means of clinical assessment questionnaires and fibroendoscopy. Is this sufficient for diagnosis? . Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2007;58(9):421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sataloff R T Commentary Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 20101369914–915. [doi:10.1001/archoto.2010.145] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]