Abstract

This study examined the relationship between emotional distress (defined as depression, brooding, and negative affect), alcohol outcomes, and bidirectional intimate partner violence among lesbian women. Results lend support to the self-medication hypothesis which predicts that lesbian women who experience more emotional distress are more likely to drink to cope, and in turn report more alcohol use, problem drinking, and alcohol-related problems. These alcohol outcomes were in turn, associated with bidirectional partner violence. These results offer preliminary evidence that, similar to findings for heterosexual women, emotional distress, alcohol use, and particularly alcohol-related problems, are risk factors for bidirectional partner violence among lesbian women.

Keywords: lesbian, alcohol use, bidirectional violence, IPV, distress, partner violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a widely recognized societal problem (McHugh, 2005) and a significant problem in the lesbian community (West, 2002). Although risk factors for IPV victimization and perpetration have begun to be identified among heterosexual women (see Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012), relatively less is known about risk factors for IPV among lesbian women. This finding is particularly troubling as recent data suggest that lesbian women experience more overall lifetime IPV compared to heterosexual women (44% vs. 35%) and experience more severe lifetime physical violence victimization (e.g., being hit with a fist, slammed against something) (Walters, Chen, & Breiding, 2013).

As understanding of IPV has advanced, so has recognition that there are different types of violence. Historically, IPV was thought to result from dominating and controlling behavior on the part of the male partner in a heterosexual dyad, rooted in a patriarchal model and gender inequalities (Baker, Buick, Kim, Moniz, & Nava, 2013; Santana, Raj, Deckler, La Marche & Silverman, 2006). As data on female perpetration of IPV accumulated, more complex models emerged. Johnson and Ferraro (2000) proposed four types of domestic violence related to the context in which IPV behaviors occur: common couple violence, intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and mutual violent control. Only intimate terrorism matches the historical conceptualization of IPV; the other three categories describe behaviors that are consistent with bidirectional partner violence (BPV). Research confirms that BPV is the most common form of IPV across all samples, including same-sex couples (Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Misra, Selwyn, & Rohling, 2012; Renner & Whitney, 2010). Moreover, among gay and bisexual men, Bartholomew, Regan, White, and Oram (2008) found a high level of bidirectionality in reports of IPV perpetration and victimization and severity of perpetrated and received abuse, leading them to speculate that “retaliation and escalation may be somewhat more likely in same-sex than in opposite-sex intimate relationships” (p. 633).

Emotional distress and alcohol use are two global factors that may increase the likelihood of IPV among heterosexual women (Capaldi et al., 2012). Compared to heterosexual women, lesbian women have higher rates of depression and anxiety disorders (Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, & McCabe, 2010) and report more suicidal and self injurious behaviors (Kerr, Santurri, & Peters, 2013). Lesbian women also engage in more harmful drinking, have higher rates of alcohol use disorders (AUDs), and are more likely to receive treatment for their drinking (e.g., Drabble, Midanik, & Trocki, 2005; Drabble, Trocki, Hughes, Korcha, & Lown, 2013; Hughes, 2011; McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, West, & Boyd, 2009). Lesbian women are also more likely to have co-occuring mental health problems and substance use disorders (Lipsky et al., 2012). Therefore, lesbian women may be at particularly high risk for IPV.

Given the association between alcohol use and IPV among heterosexual women (Foran & O’Leary, 2008), and the common occurrence of BPV among same-sex couples, we examined whether alcohol use may serve as a method of coping with negative affect and then whether emotional distress, drinking to cope, and alcohol use may directly and/or indirectly predict BPV in a sample of lesbian women.

Emotional Distress and IPV among Lesbian Women

Prospective studies of young adults have demonstrated that depressive symptoms are associated with heterosexual women’s IPV perpetration and victimization (Capaldi et al., 2012). Furthermore, depressive symptoms specifically predicted subsequent bidirectional IPV among young adult heterosexual couples (Melander, Noel, & Tyler, 2010). To our knowledge no prospective study has found a link between emotional distress and IPV among lesbian women, although reports of past year psychological distress (i.e., feeling depressed, hopeless, restless) were cross-sectionally associated with past year IPV victimization in a sample that included heterosexual, lesbian, and bisexual women (Goldberg & Meyer, 2013).

Another component of emotional distress, rumination, has also been linked to partner aggression. Individuals who engage in the maladaptive form of rumination, or brooding, fixate on their problems and engage in behaviors that create difficulties in their personal relationships (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008), including relationship aggression (Goldstein, 2010). Among lesbian women specifically, brooding has also been associated with intimate partner psychological aggression (Lewis, Milletich, Derlega, & Padilla, 2013).

Alcohol Use and IPV among Lesbian Women

Among heterosexual women, alcohol use has been associated with BPV (Cunradi, 2007; Melander et al., 2010) and IPV perpetration and victimization. Couples in which the female partner had alcohol-related problems were six times more likely to experience episodes of female-to-male IPV than couples who reported no female alcohol problems (Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 1999). Similarly, 18% of women seeking treatment for substance use had perpetrated violence against a partner or spouse (Easton, Swan, & Sinha, 2000). Problematic alcohol use (i.e., endorsing more alcohol abuse/dependence criteria) was also associated with IPV victimization (La Flair et al. 2012).

Although far fewer studies have examined alcohol use and IPV among lesbian women, both heterosexual and lesbian women who reported binge drinking daily or weekly were more likely to report IPV (physical assault/sexual violence) (Goldberg & Meyer, 2013). In a small sample of women who reported being in a same-sex romantic relationship in the past five years, Eaton et al. (2008) found a non-significant trend for lesbian women with a history of IPV (defined as physical assault, sexual coercion, destruction of property, psychological aggression, and threatening to disclosure sexual orientation) to have AUDIT scores consistent with hazardous drinking (i.e., 7 or higher) compared to lesbian women without a history of IPV. Similarly, in a study of women who had sex with other women, Glass et al. (2008) found that physical relationship violence was associated with a partner or ex-partner who misused alcohol.

Self-Medication and Drinking to Cope

The association between alcohol use and IPV may be understood in terms of a common antecedent, emotional distress. Among heterosexual women, depression was related to bidirectional physical aggression (Graham, Bernards, Flynn, Tremblay, & Wells, 2012) and among lesbian women depression was related to alcohol dependence (Bostwick, Hughes, & Johnson, 2005). The self-medication hypothesis (SMH) explains how mental health and substance problems may relate to IPV in that substance use serves as a method to reduce psychological symptoms (Khantzian, 1985). In one of the few studies to examine the association between psychological distress and alcohol use among lesbian women, anxiety, but not depression, predicted subsequent hazardous alcohol use (Johnson, Hughes, Cho, Wilsnack, Aranda, & Szalacha, 2013).

Consistent with the SMH model, some lesbian women may drink to cope with psychological distress. The reasons why someone drinks, or drinking motives, have been shown to play an important role in drinking behavior. Drinking to cope involves the use of alcohol “to escape, avoid, or otherwise regulate negative emotions” (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995, p. 991). Coping motives predict heavy alcohol use and drinking problems (Cooper, 1994; Cooper et al., 1995) and DSM-IV alcohol dependence one year later (Carpenter & Hasin, 1998). Coping drinking motives also are theorized to be predicted by negative affect (Cooper et al., 1995). Consistent with the SMH, individuals who reported higher stress and endorsed higher drinking to cope reported the highest frequency of heavy drinking (Abbey, Smith, & Scott, 1993). Thus, endorsing coping motives for drinking may represent a risk factor for problematic drinking and alcohol use disorders. Few studies, however, have examined drinking to cope among lesbian women. One prospective study of college students did test a model whereby discrimination predicted alcohol related problems through its influence on negative affect and drinking to cope motives (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2011). These researchers found that the mediating processes did not differ between lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB) and heterosexual students. Given the salience of the association between drinking to cope motives and alcohol use, it may be through this mediational pathway that psychological distress is linked to IPV.

Emotional Distress, Alcohol Use, and IPV: The Current Model

The extant literature suggests that emotional distress and alcohol use are risk factors for BPV among heterosexual women. Although few studies directly address BPV among lesbian women, we know that lesbian women are more likely that heterosexual women to report depression and anxiety as well as hazardous drinking and AUDs (Bostwick et al., 2010; Drabble et al., 2013; McCabe et al., 2009) suggesting they may also be at increased risk for BPV. The Institute of Medicine’s (2011) report on LGB health cautions researchers that combining sexual minority populations’ data may obscure differences among them. Therefore, this research focused on women who consider themselves to be lesbian and who were currently in a romantic relationship with a woman. Also, we limited the age range to 18 to 35 years because among heterosexual women, IPV occurs most frequently during these years and declines with age (cf. Thompson et al., 2006). We expected a similar pattern would occur among lesbian women.

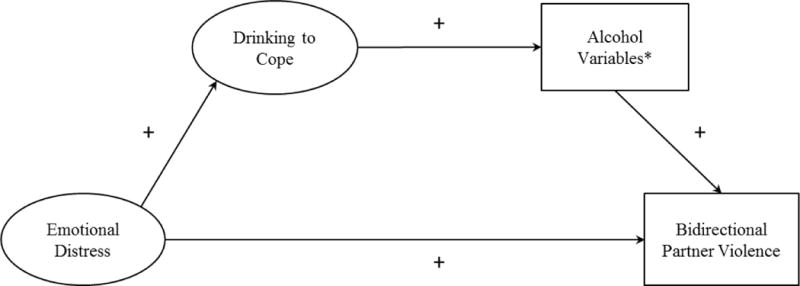

Using the SMH as a theoretical framework, we developed and tested a model of the relationship between emotional distress and BPV among lesbian women (see Figure 1). We predicted emotional distress would be directly related to BPV. Also, we expected that emotional distress would be related to BPV via its influence on drinking to cope motives and alcohol outcomes. Specifically we predicted that lesbian women drink as a way to cope with psychological distress (i.e., depression, negative affect, and rumination) which would then be associated with greater alcohol consumption, problematic drinking, and alcohol-related harms. Finally, we expected that alcohol use and related problems would be associated with BPV.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Mediation Model.

*Alcohol variables include: drinking quantity, maximum drinks consumed, and alcohol-related problems.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Four hundred forty-five self-identified lesbian women were recruited from online panels established by two market research firms. Panel members, who are recruited to participate in online surveys in exchange for rewards, are initially invited to join the panel in a variety of ways such as ads on popular websites and e-mail or postal invitations.

Participation was restricted to women who 1) initially self-identified as lesbian, 2) were between 18 and 35 years of age, 3) were in a romantic relationship with another woman for at least three months, and 4) reported physically seeing their partner at least once a month. They were invited to participate in a study about “your experiences as a lesbian, your relationships with others, and your thoughts feelings, and behaviors.” The survey completion rate for panel members who received e-mail invitations was 43%. Participants received points or rewards for completing the survey. Panel members redeem points or rewards for gift cards in a variety of categories (e.g., online shopping sites, restaurants, airlines) or donated as charitable contributions. Participants completed the online survey in approximately 30 minutes.

Based on their responses to the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), 81% of the participants (n = 360) were classified as experiencing no physical assault with their current female partner in the past year (i.e., they did not report being a perpetrator or a victim) and 12% (n = 54) were classified as experiencing bidirectional physical assault with their current female partner (i.e., they reported at least one instance of both perpetration and victimization in the past year). The remaining 7% of the sample (n = 31) included 3% (n =12) who reported at least one act of physical assault perpetration and no victimization, 2% (n = 8) who reported no perpetration and at least one act of victimization, and 3% (n = 11) who had missing data on at least one of the subscales and therefore could not be classified. The final sample (N = 414) used in all analyses related to IPV included only those participants who reported no partner violence or bidirectional partner violence (BPV) with their current female partner in the previous year.

The mean age of participants was 29.26 years (SD = 4.04) and participants represented different geographical locations in the U.S.: South (28.1%), West, (27.0%), East (23.6%), and Midwest (21.3%). The mean relationship length was 3.94 years (SD = 3.25). Additional demographic characteristics about the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of Sample

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 36 | 8.7 |

| American Indian and Alaska native | 2 | 0.5 |

| Asian | 15 | 3.6 |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.2 |

| White | 335 | 80.9 |

| Other | 20 | 4.8 |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 1.2 |

| Highest educational level | ||

| High school graduate | 29 | 7.0 |

| Some college | 77 | 18.6 |

| Associate’s degree | 41 | 9.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 152 | 36.7 |

| Master’s degree | 90 | 21.7 |

| Doctoral/professional degree | 24 | 5.8 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 |

| Annual income | ||

| < $50,000 | 171 | 41.3 |

| $50,000 to < $100,000 | 141 | 34.0 |

| $100,000 to < $150,000 | 64 | 15.5 |

| > $150,000 | 15 | 3.6 |

| Declined to answer | 23 | 5.6 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Partnered, in a causal relationship | 24 | 5.8 |

| Partnered, in a committed relationship | 290 | 70.0 |

| Partnered, married, or in a civil union | 92 | 22.2 |

| Other | 8 | 1.9 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Only homosexual/lesbian | 310 | 74.9 |

| Mostly homosexual/lesbian | 97 | 23.4 |

| Other | 7 | 1.7 |

| How open are you about your sexual preference? | ||

| I work very hard to hide it | 1 | 0.2 |

| I selectively tell people I trust | 60 | 14.5 |

| I am not too worried about people knowing | 229 | 55.3 |

| I never hesitate to tell people | 123 | 29.7 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.2 |

| Lifetime sexual behaviora | ||

| Women only | 155 | 37.4 |

| Women and men | 258 | 62.3 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.2 |

| Past year sexual behaviorb | ||

| Women only | 397 | 95.4 |

| Women and men | 17 | 4.1 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 0.5 |

| Sexual attraction | ||

| Only women | 244 | 58.9 |

| Mostly women | 170 | 41.1 |

Note. N = 414;

Participants were asked, “During your lifetime, with whom have you had sex?”

Participants were asked, “During the past year, with whom have you had sex?”

Measures

Negative affect

Five items from Watson, Clark, and Tellegen’s (1988) Positive and Negative Affect schedule (PANAS) measured negative affect. Respondents rated the degree to which they felt distressed, upset, shamed, nervous, and afraid during the past 90 days from 1 (very slightly/not at all) to 5 (extremely). Higher scores reflected more negative affect. These items demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .90) in a sample of LGB participants (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009).

Rumination

The five-item Brooding subscale of the Responses Styles Questionnaire (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003) assessed rumination. Rumination was defined as, “passive comparison of one’s current situation with some unachieved standard” (p. 256). Participants reported how often during the past 90 days they experienced thoughts such as, “What am I doing to deserve this?” and, “Why do I always react this way?” using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). In previous research, the Brooding subscale displayed good psychometric properties (Treynor et al., 2003) in general and good internal consistency (α = .85) in a sample of LGB participants (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009).

Depressive symptoms

The short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Andresen, Mamgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994) assessed participants’ depressive symptoms. Using response choices ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time), participants reported how frequently they experienced 10 behaviors/thoughts (e.g., “I felt that everything I did was an effort” and “I felt fearful”) during the past week. The 10-item CES-D has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Cole, Rabin, Smith, & Kaufman, 2004).

Drinking to cope

Participants completed the five-item Coping subscale from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994). Participants indicated the amount of time they drink to cope (e.g., “To cheer up when you are in a bad mood” and “To forget your worries”) using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (all of the time). The drinking to cope subscale has been shown to be internally consistent (α = .85) and is associated with usual drinking quantity and frequency, heavy drinking, and drinking problems (Cooper, 1994).

Alcohol use variables

Participants used the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) 7-day grid to provide the number of ‘standard’ drinks typically consumed weekly over the past 90 days. A standard drink is defined as one 12 oz beer, 1 ½ oz of liquor, or 5 oz of wine. Drinking quantity was calculated as the sum of drinks reported per week. Maximum drinks consumed were determined by the greatest number of drinks consumed on any given drinking day reported on the DDQ. The DDQ has convergent validity with other measures of alcohol use (Collins et al., 1985; Collins & Lapp, 1992). Maximum drinks have been shown to predict alcohol consequences and dependence symptoms (Greenfield, Nayak, Bond, Ye, & Midanik, 2006).

Alcohol-related problems

The Short Index of Problems (SIP-2R; Miller, Tonigan & Longabaugh, 1995) is a 15-item measure that assessed alcohol-related consequences over the past 90 days. Respondents indicated the degree to which certain experiences occurred (e.g., “I have been unhappy because of my drinking” and “I have failed to do what is expected of me because of my drinking”) using a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) not at all to (4) very much. Miller et al. (1995) reported good psychometric properties for the SIP-2R.

Bidirectional partner violence

The Physical Assault subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) assessed participants’ reports of perpetrating (e.g., “I slapped my partner”) and being the victim of physical assault (e.g., “My partner slapped me”) in the past year. Participants responded to 12 items for victimization and 12 items for perpetration indicating the frequency of aggressive acts during the past year using count-based anchors ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Item scores were summed to reflect two total frequency scores: past-year frequency of physical assault perpetration and past-year frequency of physical assault victimization. Among sexual minority individuals, the Physical Assault Perpetration subscale of the CTS2 has been found to be internally consistent (α = .92) (McKenry, Serovich, Mason, & Mosack, 2006) and has demonstrated convergent validity with the CTS-2 Psychological Aggression subscales (Matte & Lafontaine, 2011).

Results

Overview of Analyses

Prior to testing the conceptual model, separate confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) for the measurement instruments were conducted (Mueller & Hancock, 2008). Missing data for all CFAs were addressed with full information maximum likelihood (Schafer, 1997). Model adjustments for CFAs were considered by consulting the approximate decreases in chi-square with one degree of freedom if the corresponding parameter is freely estimated (i.e., the modification index). A high modification index indicates that the corresponding parameter should be freely estimated to improve model fit; only modification indices greater than 10 were considered. In addition, normal theory bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for all Cronbach αs using 1,000 bootstrap samples (Padilla, Divers, & Newton, 2012). Following CFAs for measures of negative affect, rumination, and depression, items from these scales were parceled to create a latent variable labeled Emotional Distress (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). The Drinking to Cope measure was based on a CFA of the subscale from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire. Drinking quantity and maximum drinks were not subject to CFAs; however the measure of alcohol-related problems was based on a CFA of the SIP-2R.

The conceptual model was fitted with a Bayesian structural equation model (BSEM). When models have continuous predictor variables and categorical outcome variables, BSEM reduces or eliminates the computational difficulties of classical SEM analyses when estimating indirect effects and provides model assessment statistics (Gelman, Carlin, Stern, & Rubin, 2004; Lee, 2007). A probit model was used for the categorical outcome variable. All BSEMs were estimated using two chains of 20,000 posterior samples, 10,000 to establish a stationary distribution (e.g., burn-in period) and 10,000 post-burn-in and with thinning set at 5, that is, keeping every 5th sample and discarding others in order to reduce autocorrelation between samples. Non-informative (or diffused) priors were used for all model parameters.

Statistical significance for unstandardized parameter estimates was assessed using highest density intervals (HDIs; Kruschke, 2011). For all HDIs, the parameter estimate is statistically significant if zero is not present in the HDI. The HDI is also referred to as the highest density region (HDR), highest probability density (HPD), or highest posterior density (HPD). All posteriors were conducted at α = .05. Model fit was assessed using posterior predictive checking with the following criteria: posterior predictive p-value > .10 and a chi-square difference test between the observed and replicated data confidence interval (CI) that captures zero (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012). Missing data were imputed internally under the specified BSEM model.

Measurement Models

The one factor CFAs for the negative affect, rumination, and depressive symptoms measures indicated questionable fit. Based on modification indices, items that were semantically similar to other items were removed in the interest of parsimony and to maintain a clear factor structure (cf. Doane, Kelley, Chiang, & Padilla, 2013). A latent factor (labeled Emotional Distress) was then created from parcels of the remaining negative affect, rumination, and depressive symptoms items; i.e., three parcels.

Both the CFAs for the Drinking to Cope and SIP-2R measures had questionable fit. Based on modification indices and conceptual considerations, two and six items, respectively were removed. Table 2 contains all relevant CFA information and the SIP-2R retained items.

Table 2.

Summary of Variable Measurement Models

| Variable | # of Items | Chi Square | p value | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Affect | ||||||||

| Initial Model | 5 | χ2 (5, N= 445) = 41.47 | <.001 | .947 | .893 | .128 | .037 | |

| Final Model | 4 | χ2 (5, N= 445) = .08 | 0.996 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .000 | .001 | .76 [.72, .80] |

|

| ||||||||

| Rumination | ||||||||

| Initial Model | 5 | χ2 (5, N= 445) = 50.21 | <.001 | .945 | .890 | .143 | .038 | |

| Final Model | 4 | χ2 (5, N= 445) = 14.75 | 0.001 | .976 | .927 | .120 | .026 | .80 [.76, .84] |

|

| ||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||||||

| Initial Model | 10 | χ2 (35, N= 445) = 160.11 | <.001 | .906 | .879 | .090 | .053 | |

| Final Model | 9 | χ2 (35, N= 445) = 78.15 | <.001 | .958 | .944 | .065 | .035 | .85 [.82, .87] |

|

| ||||||||

| Drinking to Cope | ||||||||

| Initial Model | 5 | χ2 (5, N= 445) = 55.41 | <.001 | .961 | .922 | .151 | .036 | |

| Intermediate Model | 4 | χ2 (5, N= 445) = 14.20 | 0.001 | .985 | .956 | .117 | .020 | |

| Final Model | 3 | df = 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | .87 [.83, .90] |

|

| ||||||||

| SIP- 2Rab | ||||||||

| Initial Model | 15 | χ2 (90, N= 407) = 960.94 | <.001 | .773 | .735 | .154 | .076 | |

| Final Model | 9 | χ2 (27, N= 407) = 269.66 | <.001 | .882 | .842 | .149 | .056 | .89 [.82, .94] |

Notes. Numbers in brackets are coefficient α 95% normal theory bootstrap confidence intervals with 1,000 bootstrap samples.

SIP – Short Index of Problems that measures alcohol-related problems.

Final model retained items: 1. I have been unhappy because of my drinking. 3. I have failed to do what was expected of me because of my drinking. 6. When drinking, I have done impulsive things that I regretted later. 7. My physical health has been harmed by my drinking. 10. My family has been hurt by my drinking. 11. A friendship or close relationship has been damaged by my drinking. 12. My drinking has gotten in the way of my growth as a person. 13. My drinking has damaged my social life, popularity, or reputation. 14. I have spent too much or lost a lot of money because of my drinking.

Bidirectional partner violence (BPV)

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) was used to create a binary BPV variable (0 = no violence, 1 = bidirectional partner violence). Items reflecting physical assault perpetration and victimization were summed separately. Participants who did not endorse any physical assault perpetration or victimization received a BPV score of “0.” Participants who reported at least one incident of both physical assault perpetration and victimization received a BPV score of “1.”

Test of the Hypothesized Model

After establishing the measurement models through CFAs (see Table 3 for descriptive information), structural paths were added based on the hypothesized model (see Figure 1). All BSEM models had good convergence as there were no patterns in the trace plots and autocorrelations were near zero.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BPVa | – | |||||||

| 2. Negative affect | .12* | – | ||||||

| 3. Rumination | .15** | .65*** | – | |||||

| 4. Depressive symptoms | .05 | .66*** | .63*** | – | ||||

| 5. Coping motives | .11* | .41*** | .39*** | .44*** | – | |||

| 6. Alcohol problems | .22*** | .21*** | .22*** | .20*** | .38*** | – | ||

| 7. Max. drinks consumed | .15** | −.08 | .07 | .03 | .14** | .31*** | – | |

| 8. Drinking quantity | .13** | −.05 | .04 | .03 | .23*** | .41*** | .80*** | – |

| M | 0.13b | 8.49 | 7.46 | 5.82 | 5.19 | 0.96 | 3.55 | 8.34 |

| SD | – | 2.99 | 2.60 | 4.76 | 2.82 | 2.62 | 3.51 | 8.88 |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 20.00 | 16.00 | 24.00 | 16.00 | 24.00 | 36.00 | 60.00 |

| Skewness | – | 0.96 | 1.10 | 1.18 | 1.58 | 4.79 | 4.85 | 2.56 |

| Kurtosis | – | 0.83 | 1.07 | 1.26 | 1.87 | 28.41 | 36.99 | 8.81 |

| % missing data | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.72 | 0.97 | 0.24 | 8.94 | 8.54 | 8.94 |

Note.

Coded 1 = bidirectional partner violence, 0 = violence.

Mean can be interpreted as proportion of sample coded 1.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

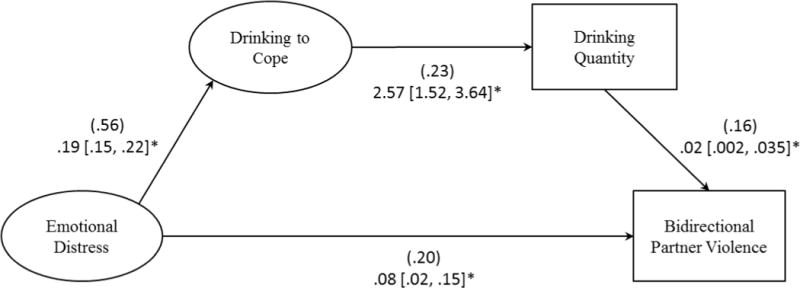

Drinking quantity

The overall model of number of drinks per week had adequate fit (see Figure 2). The direct effects of emotional distress to both BPV and drinking to cope were positive and significant. The direct effects from drinking to cope to drinking quantity and drinking quantity to BPV were also positive and significant. In addition, emotional distress was indirectly related to BPV via drinking to cope and drinking quantity. Specifically, greater emotional distress was associated with increased drinking to cope which in turn was associated with more drinking which in turn was associated with a greater likelihood of BPV.

Figure 2. Drinking Quantity Fitted Mediation Model.

*Indicates statistical significance based on 95% (α=.05) HDI.

All estimates based on 20,000 posterior samples with 10,000 post-burn-in and thinning = 5.

Standardized estimates are in parentheses followed by unstandardized estimates and, in brackets, HDIs.

Indirect effect: .01 .001, .019*. Model posterior predictive, p = .196, observed-replicated data Δχ2 95% CI −14.86, 35.81.

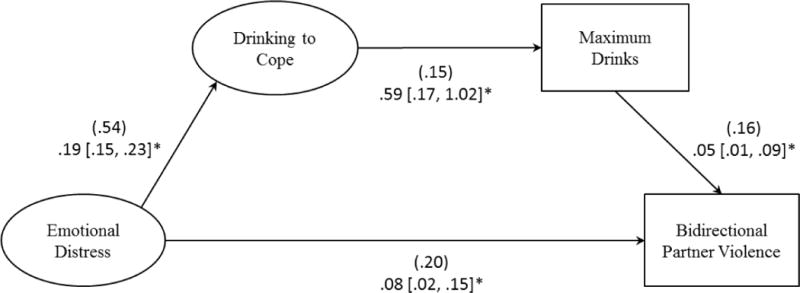

Maximum drinks consumed

The overall model of maximum drinks also had good fit (see Figure 3). The direct effects of emotional distress to both BPV and drinking to cope were positive and significant. Likewise, the direct effects from drinking to cope to maximum drinks and maximum drinks to BPV were positive and significant. In addition, emotional distress was indirectly related to BPV via drinking to cope and maximum drinks. Specifically, higher emotional distress was associated with increased drinking to cope which in turn was associated with more maximum drinks which in turn was associated with a greater likelihood of BPV.

Figure 3. Maximum Drinks Fitted Mediation Model.

*Indicates statistical significance based on 95% (α=.05) HDI.

All estimates based on 20,000 posterior samples with 10,000 post-burn-in and thinning = 5.

Standardized estimates are in parentheses followed by unstandardized estimates and, in brackets, HDIs.

Indirect effect: .01 .001, .013 *. Model posterior predictive p = .273, observed-replicated data Δχ2 95% CI −19.20, 32.09.

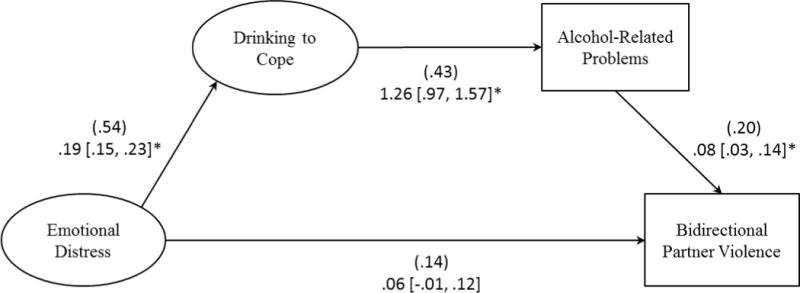

Alcohol-related problems

The model based on the SIP-2R had excellent fit (see Figure 4). The direct effect of emotional distress to drinking to cope was positive and significant, but the direct effect from emotional distress to BPV was not significant. The direct effects from drinking to cope to alcohol-related problems and alcohol-related problems to BPV were also positive and significant. In addition, emotional distress was indirectly related to BPV via drinking to cope and alcohol-related problems. Specifically, higher emotional distress was associated with increased drinking to cope which in turn was associated with more alcohol-related problems which in turn was associated with a greater likelihood of BPV. Contrary to the predicted partial mediation, the model was best fit with a fully mediated relationship from emotional distress to BPV via drinking to cope and alcohol-related problems.

Figure 4. Alcohol-Related Problems Mediation Model.

*Indicates statistical significance based on 95% (α=.05) HDI.

All estimates based on 20,000 posterior samples with 10,000 post-burn-in and thinning = 5.

Standardized estimates are in parentheses followed by unstandardized estimates and, in brackets, HDIs.

Indirect effect: .02 .006, .035 *. Model posterior predictive p = .442, observed-replicated data Δχ2 95% CI. −22.95, 27.78.

Discussion

In our online sample of over 400 participants, 12% reported past year BPV, a common pattern of IPV in which individuals identify themselves as both perpetrators and victims of physical violence in an intimate relationship. Although this is a relatively small percentage of our overall community based sample, it is consistent with 13% of young adults who reported BPV in a large U.S. probability sample (Melander et al., 2010).

As expected, and consistent with findings among heterosexual women (e.g., Melander et al., 2010), there was a direct effect between emotional distress and BPV for two of the three tested models, such that lesbian women who reported more emotional distress were more likely to report BPV. Importantly, in every model emotional distress was also indirectly associated with BPV via drinking to cope and the alcohol use variables (i.e., drinking quantity and maximum drinks consumed [reflecting problem drinking]). This finding suggests that emotional distress, defined by negative affect, brooding, and depression, is an important risk factor for violence in a lesbian sample both due to its direct effect on BPV but also due to its indirect effect through alcohol use in an apparent effort to cope with the negative affect.

The connection between emotional distress and relationship dissatisfaction and conflict has been frequently studied. While problems in a relationships no doubt lead to personal distress, there is also a strong argument that an individual’s emotional distress can lead to irritability and hostility, that when expressed towards one’s partner can provoke conflict and even IPV (Marshall, Jones, & Feinberg, 2011). Although our cross-sectional data do not permit us to determine directionality, our study replicates recent work by Goldberg and Meyer (2013) who found that psychological distress was associated with IPV victimization among LB women. Furthermore, our results lend support to the self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1985) by demonstrating that among lesbian women emotional distress is associated with drinking to cope which in turn is associated with greater alcohol use and problem drinking and these are directly associated with more BPV. Thus, emotional distress is associated with BPV in a lesbian sample both through its direct influence and the indirect self-medication path.

The model using alcohol-related problems yielded the best fit with the data. Although we proposed partial mediation, our results produced a fully mediated model. Emotional distress had a positive, but not statistically significant, direct effect on BPV but a stronger (compared to the other models) indirect effect through drinking to cope and alcohol problems. These data suggest that drinking to cope has a strong relationship with alcohol problems, which in turn is related to BPV. Whereas alcohol use and problems are fundamentally related, there is variance in alcohol-related problems that is not accounted for by alcohol use alone. For example, Borsari, Neal, Collins, and Carey (2001) found that alcohol use explained less than 50% of the variance in alcohol problems. In the current sample the correlation between alcohol problems and drinking quantity and maximum drinks consumed were r = .41 and .31, respectively. Research suggests that individuals with psychological difficulties (e.g., depression, negative affect, stress) experience more alcohol-related harms (e.g., Geisner, Larimer, & Neighbors, 2004) but may not have higher rates of drinking (e.g., Camatta & Nagoshi, 1995). In the current sample, the modified SIP-2R was in fact modestly related to negative affect, rumination, and depression (rs = .20 – .22). McCreary and Sadava (1998) further supported this notion by finding that individuals who experienced more chronic stressors were more likely to be at risk for alcohol-related problems but not increased alcohol consumption. Similar results have been found among individuals with psychological distress and depression (Martens et al. 2008; Oliver, Reed, & Smith, 1998). Clearly, alcohol-related problems capture an aspect of problematic drinking that is not identical to drinking quantity and may be a more serious risk factor for lesbian couples.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although we tested a traditional distress-motivated alcohol pathway and its impact on BPV, we acknowledge the limitations of our cross sectional design. Emotional distress and IPV can both be antecedents or consequences of hazardous drinking (Hughes, 2011; Johnson et al., 2013). Further, it is possible that emotional distress is an outcome of physical assault rather than a predictor. Thus, a possible competing model may be one where physical assault leads to greater emotional distress, greater likelihood of drinking to cope, and ultimately, more severe drinking outcomes. Future research utilizing prospective designs is warranted to help elucidate the nature of the temporal relationships among these key constructs.

Our geographically diverse sample of self-identified lesbian women was recruited through an online marketing research panel. As a result, they were relatively open about their sexual orientation and relatively well educated. Therefore, our results cannot be generalized to women who may be less open about their sexual orientation or bisexual. In particular, it is important to examine the IPV risk profile for bisexual women as they may experience violence in both same- and opposite-sex relationships.

We also recognize that categorizing individuals as bidirectionally violent based on the presence or absence of self-report of perpetration and victimization of physical assault obscures information about the frequency of relationship aggression. This approach is often necessitated in community samples due to the low base rate of violent behavior. Furthermore, given the limitations of measurement of IPV, our assessment of BPV did not take into account important contextual information about the nature of this violence.

There may also be important variables that need to be added to our model of BPV in future investigations. Although the model fit statistics for the variables tested were adequate to excellent, the paths themselves, especially the indirect paths, generally represent small effects. Although emotional distress and alcohol variables are clearly risk factors, a more thorough explanation of BPV will include other variables. As Meyer (2003) suggested, since lesbians experience minority stress as members of a stigmatized and marginalized group assessment of discrimination or expectations of rejection may be important. We have alluded before to the connection between emotional distress and relationship conflict. Therefore, including relationship variables, such as, conflict, satisfaction, communication, and problem solving skills, may also add to the adequacy of our models explaining BPV in lesbian couples.

Clinical Implications

Our findings highlight the role of both emotional distress and alcohol involvement in BPV in lesbian couples. Interventions that are successful in reducing either or both of these factors may also reduce relationship violence. For example, a cognitive-behavioral intervention for women with PTSD reduced PTSD and depressive symptoms and also likelihood of IPV victimization (Iverson et al., 2011). While the model and the data in the current study are cross-sectional, the implication of a self-medication model is a potential downward spiral. As emotional distress leads one to drink as a way of coping, this can lead to BPV which no doubt leads to even more distress, and ultimately individuals may find themselves engaging in dysfunctional behaviors that are difficult to modify. Interventions that focus on regulating negative emotional states without the use of alcohol (Bradizza & Stasiewicz, 2009) may help disrupt this downward spiral. Further, Behavioral Couples Therapy has been effective in reducing alcohol use and enhancing relationship satisfaction in heterosexual couples (Schumm, O’Farrell, & Burdzovic, 2012) however, its effects with gay and lesbian couples remains to be demonstrated. An advantage of couple’s intervention may be that in addition to reducing alcohol consumption, it reduces conflict which has a positive impact on both emotional distress and IPV. In the end, clinical interventions that ameliorate any piece of the cycle may have a positive impact on other parts of the cycle.

Summary

As data from probability samples of sexual minority women accumulate, there is mounting evidence that lesbian women experience more emotional distress, report more alcohol use, AUDs, alcohol-related problems, and IPV compared to heterosexual women (Bostwick et al., 2010; Drabble et al., 2005; 2013; Walters et al., 2013). Our results offer a potential explanation for the high rates of some of these problems. Although our results do not explain the higher rates of emotional distress, they do suggest that lesbians may drink to cope with this distress and then, similar to heterosexuals who drink to cope, experience alcohol-related problems. Importantly, our results extend the outcomes one step further and suggest that alcohol use and related problems are also associated with BPV in lesbians as has been shown among heterosexual women. As these risk factors for IPV among lesbians are identified, it is essential that culturally sensitive prevention, early intervention, and treatment programs are developed and empirically examined to reduce emotional distress, alcohol involvement, and ultimately IPV in the lesbian community.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism under the NIH Award Number R15AA020424 to Robin J. Lewis (PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

The Harris Interactive Service Bureau (HISB) was responsible solely for the data collection in this study. The authors were responsible for the study’s design, data analysis, reporting the data, and data interpretation.

Biographies

Robin J. Lewis, Ph.D. is a professor of psychology and graduate program director for the clinical psychology Ph.D. program at Old Dominion University affiliated with the Virginia Consortium Program in Clinical Psychology. Her research focuses on sexual minority health and reducing health disparities for sexual minority women. She is particularly interested in how minority stress contributes to alcohol use and violence among sexual minority women.

Miguel A. Padilla, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of quantitative psychology in the Department of Psychology at Old Dominion University. His research interests are in psychometrics, applied statistics, and statistical computing.

Robert J. Milletich, M.S. is a doctoral student in the Applied Experimental Psychology program at Old Dominion University. Broadly, his research has focused on predictors and consequences of intimate partner violence among both opposite- and same-sex couples. More recently, he has begun focusing on measurement issues associated with intimate partner violence.

Michelle L. Kelley, Ph.D. is a developmental psychologist and professor of psychology at Old Dominion University. Her work has focused on the multigenerational effects of parental alcohol or drug use disorder on their children, the intersection of substance abuse and intimate partner violence, treatment for alcohol- or drug-abuse treatment, and factors that serve to protect children of substance abusers from the potential negative effects of residing with a substance-abusing parent.

Cathy Lau-Barraco, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of psychology at Old Dominion University. Her research focuses on the determinants of substance use, with an emphasis on the emerging adulthood developmental period. She is particularly interested in the individual-level, social, and contextual factors associated with use. Her work also focuses on developing strategies to target heavy drinking among understudied populations.

Barbara A. Winstead, Ph.D. is professor of psychology at Old Dominion University and a clinical faculty member with the Virginia Consortium Program in Clinical Psychology. Her research focuses on gender and relationships, including interpersonal violence and unwanted pursuit/stalking and the effects of relationships and self-disclosure on coping with stress and illness.

Tyler B. Mason, M.S. is a doctoral student in applied experimental psychology at Old Dominion University. His research focuses broadly in health psychology with specific interest in health behaviors, eating behaviors, and obesity. He is currently researching interventions to reduce health disparities in obesity, eating behaviors, and physical activity among lesbians.

References

- Abbey A, Smith MJ, Scott RO. The relationship between reasons for drinking alcohol and alcohol consumption: An interactional approach. Addictive Behaviors. 1993;18:659–670. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NL, Buick JD, Kim SR, Moniz S, Nava KL. Lessons from examining same-sex intimate partner violence. Sex Roles. 2013;69:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0218-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Regan KV, White MA, Oram D. Patterns of abuse in male same-sex relationships. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:617–636. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Neal DJ, Collins SE, Carey KB. Differential utility of three indexes of risky drinking for predicting alcohol problems in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:321–324. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.15.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, Johnson T. The co-occurrence of depression and alcohol dependence symptoms in a community sample of lesbians. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2005;9(3):7–18. doi: 10.1300/J155v09n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradizza CM, Stasiewicz PR. Alcohol and drug use disorders. In: Salzinger K, Serper M, editors. Behavioral Mechanisms and Psychopathology: Advancing the Explanation of Its Nature, Cause, and Treatment. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Camatta CD, Nagoshi CT. Stress, depression, irrational beliefs, and alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. A prospective evaluation of the relationship between reasons for drinking and DSM-IV alcohol-use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:41–46. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(97)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JC, Rabin AS, Smith TL, Kaufman AS. Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D short form. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:360–372. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Lapp WM. The Temptation and Restraint Inventory for measuring drinking restraint. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:625–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation for a four factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Frone M, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–990. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark CL, Schafer J. Alcohol-related problems and intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1492–1501. doi: 10.1097/00000374-199909000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB. Drinking level, neighborhood social disorder, and mutual intimate partner violence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1012–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doane AN, Kelley ML, Chiang ES, Padilla MA. Development of the Cyberbullying Experiences Survey. Emerging Adulthood (advanced publication) 2013 doi: 10.1177/2167696813479584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Midanik LT, Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: Results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE. Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0031486. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton CJ, Swan S, Sinha R. Prevalence of family violence in clients entering substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000;18:23–28. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(99)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton L, Kaufman M, Fuhrel A, Cain D, Cherry C, Pope H, Kalichman SC. Examining factors co-existing with interpersonal violence in lesbian relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:697–705. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9194-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical psychology review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner I, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: Gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Rubin DB. Bayesian data analysis. 2. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Glass N, Perrin N, Hanson G, Bloom T, Gardner E, Campbell JC. Risk for reassault in abusive female same-sex relationships. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1021–1027. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117770.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg NG, Meyer IH. Sexual orientation disparities in history of intimate partner violence: Results from the California health interview survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28:1109–1118. doi: 10.1177/0886260512459384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SE. Relational aggression in young adults’ friendships and romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 2010;18:645–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01329.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Bernards S, Flynn A, Tremblay PF, Wells S. Does the relationship between depression and intimate partner aggression vary by gender, victim-perpetrator role, and aggression severity? Violence and Victims. 2012;27:730–743. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.27.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Nayak MB, Bond J, Ye Y, Midanik LT. Maximum quantity consumed and alcohol-related problems: Assessing the most alcohol drunk with two measures. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1576–1582. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Discrimination and alcohol-related problems among college students: A prospective examination of mediating effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among sexual minority women. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2011;29:403–435. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2011.608336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Gradus JL, Resick PA, Suvak MK, Smith KF, Monson CM. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future intimate partner violence among interpersonal trauma survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:193–202. doi: 10.1037/a0022512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Ferraro KJ. Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: Making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:948–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00948.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TP, Hughes TL, Cho YI, Wilsnack SC, Aranda F, Szalacha LA. Hazardous drinking, depression, and anxiety among sexual-minority women: Self-medication or impaired functioning? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:565–575. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DL, Santurri L, Peters P. A comparison of lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual college undergraduate women on selected mental health issues. Journal of American College Health. 2013;61:185–194. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.787619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruschke JK. Bayesian assessment of null values via parameter estimation and model comparison. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:299–312. doi: 10.1177/1745691611406925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Flair LN, Bradshaw CP, Storr CL, Green KM, Alvanzo A, Crum RM. Intimate partner violence and patterns of alcohol abuse and dependence criteria among women: A latent class analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:351–360. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Misra TA, Selwyn C, Rohling ML. Rates of bidirectional versus unidirectional intimate partner violence across samples, sexual orientations, and race/ethnicities: A comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:199–230. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Structural equation modeling: A Bayesian approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Derlega VJ, Padilla MA. Sexual minority stressors and psychological aggression in lesbians’ intimate relationships: The mediating roles of rumination and relationship satisfaction. Manuscript under review 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky S, Krupski AK, Roy-Byrne P, Huber A, Lucenko BA, Mancuso D. Impact of sexual orientation and co-occurring disorders on chemical dependency treatment outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:401–412. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Jones DE, Feinberg ME. Enduring vulnerabilities, relationship attributions, and couple conflict: An integrative model of the occurrence and frequency of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:709–718. doi: 10.1037/a0025279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Martin JL, Hatchett ES, Fowler RM, Fleming KM, Karakashian MA, Cimini MD. Protective behavioral strategies and the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:535–541. doi: 10.1037/a0013588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matte M, Lafontaine MF. Validation of a measure of psychological aggression in same-sex couples: Descriptive data on perpetration and victimization and their association with physical violence. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2011;7:226–244. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2011.564944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh MC. Understanding gender and intimate partner abuse. Sex Roles. 2005;52:717–724. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-4194-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Sadava SW. Stress, drinking, and the adverse consequences of drinking in two samples of young adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:247–261. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.12.4.247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKenry PC, Serovich JM, Mason TL, Mosack K. Perpetration of gay and lesbian partner violence: A disempowerment perspective. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:233–243. doi: 10.1007/s10896-006-9020-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melander LA, Noel H, Tyler KA. Bidirectional, unidirectional, and nonviolence: A comparison of the predictors among partnered young adults. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:617–630. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. (NIH Publication No. 95-3911). [Google Scholar]

- Mueller RO, Hancock GR. Best practices in structural equation modeling. In: Osborne JW, editor. Best practices in quantitative methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 488–508. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Bayesian structural equation modeling: A more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:313–335. doi: 10.1037/a0026802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JM, Reed CK, Smith BW. Patterns of psychological problems in university undergraduates: Factor structure of symptoms of anxiety and depression, physical symptoms, alcohol use, and eating problems. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal. 1998;26:211–232. doi: 10.2224/sbp.1998.26.3.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla M, Divers J, Newton M. Coefficient Alpha bootstrap confidence interval under non normality. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2012;36:331–348. doi: 10.1177/0146621612445470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed E. Intimate partner violence: A gender-based issue? American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:197–198. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner LM, Whitney SD. Examining symmetry in intimate partner violence among young adults using socio-demographic characteristics. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25:91–106. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9273-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santana MC, Raj A, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, O’Farrell TJ, Andreas JB. Behavioral Couples Therapy when both partners have a current alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2012;30:407–421. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2012.718963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RS, Bonomi AE, Anderson M, Reid RJ, Dimer JA, Carrell D, Rivara FP. Intimate partner violence: prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West CM. Lesbian intimate partner violence: Prevalence and dynamics. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2002;6:121–127. doi: 10.1300/J155v06n01_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]