Abstract

Rationale

Histological examination of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) tissues demonstrates extracellular matrix (ECM) destruction and infiltration of inflammatory cells. Previous work with mouse models of AAA has shown that anti-inflammatory strategies can effectively attenuate aneurysm formation. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) is a matricellular protein involved in the maintenance of vascular structure and homeostasis through the regulation of biological functions such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, and adhesion. Expression levels of TSP1 correlate with vascular disease conditions.

Objective

To use TSP1 deficient (Thbs1−/−) mice to test the hypothesis that TSP1 contributes to pathogenesis of AAAs.

Methods and Results

Mouse experimental AAA was induced either through perivascular treatment with calcium phosphate, intraluminal perfusion with porcine elastase, or systemic administration of Angiotensin II. Induction of AAA increased TSP1 expression in aortas of C57BL/6 or apoE−/− mice. Compared to Thbs1+/+ mice, Thbs1−/− mice developed significantly smaller aortic expansion when subjected to AAA inductions, which was associated with diminished infiltration of macrophages. Thbs1−/− monocytic cells had reduced adhesion and migratory capacity in vitro compared to wildtype counterparts. Adoptive transfer of Thbs1+/+ monocytic cells or bone marrow reconstitution rescued aneurysm development in Thbs1−/− mice.

Conclusions

TSP1 expression plays a significant role in regulation of migration and adhesion of mononuclear cells, contributing to vascular inflammation during AAA development.

Keywords: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, matrix protein, inflammation, monocyte, matricellular gene

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), the progressive weakening and dilation of the aortic wall, is a common, age-related vascular disease. While the precise disease etiology remains elusive, women demonstrate protection from the disease prior to menopause, and both aging and smoking are to be major risk factors associated with AAA 1, 2. Despite the many recent advances in AAA imaging and surgical interventions, the majority of patients who are diagnosed with small (5.5 cm for men and 5cm for women), asymptomatic AAAs are left untreated due to the low benefit-to-risk ratio of surgical interventions in this patient population 3, 4. Laboratory research that focuses on understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying aneurysm development and progression is vital to the design of effective pharmacological therapies with which to slow or reverse aneurysm progression in this population.

Over the past few decades, multiple studies have utilized both human tissues and animal models to explore the complex underlying pathophysiology of AAA. Animal models have been developed to replicate histological features of AAA such as disrupted elastin fibers, a diminished number of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and transmural infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes 5–8. Evidence from these studies has indicated that the progressive disruption of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, particularly elastin and collagen, is a key event that leads to weakening and dilation of the aortic wall. Further, several classes of the matrix-degrading enzymes matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are implicated in aneurysm pathophysiology. Elevated MMP proteins found in human aneurysmal tissues were reported to correlate with aneurysm diameters 9–11. Additionally, manipulation of MMPs, either through pharmacological inhibition or through genetic deletion inhibits aneurysm development in mice 12–14. One such pharmacological inhibitor, doxycycline, is currently being tested in multi-centered clinical trials for the treatment of small aneurysm 15–17.

Infiltration of inflammatory cells is another pathological event that has received substantial attention in aneurysm research. Macrophages are believed to be the major source of MMPs 11, 13, 18, 19 and pro-inflammatory cytokines 20–22. Experimental strategies that reduce the macrophage population in the aneurysm wall, whether through macrophage depletion or cytokine inhibition, lead to lower MMP activity and attenuate aneurysm formation in mouse models of AAA 23–25.

Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) is a member of the matricellular TSP protein family. Matricellular proteins are nonstructural extracellular proteins that integrate into the structural ECM. TSP1 exists naturally as a homotrimeric glycoprotein. Each monomer contains an N-terminal globular module (N), a central stalk region, and a globular C-terminal assemblage. Through these modules or domains, TSP1 binds to various matrix proteins, integrins, and cell surface receptors including CD36 and CD47 26. TSP1 modulates a wide range of biological functions including cell adhesion 27, inhibition of angiogenesis and endothelial cell proliferation 28, and activation of latent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)29, 30. Additionally, TSP1 acts as a chemo-attractant that impacts various inflammatory cells 27, and enhanced levels of TSP1 are reported in conditions associated with tissue damage and inflammation 31, 32. However, targeted gene deletion of Thbs1 produces mixed effects on the inflammatory responses depending upon the disease models. For instance, Moura et al demonstrated that Thbs1 deficiency accelerates atherosclerotic plaque maturation and is associated with higher macrophage-mediated inflammation in ApoE−/− mice 33. Using a diet-induced mouse model of obesity, Li et al reported that the lack of TSP1 reduces obesity-associated inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity specifically through the reduction of both adhesion, migration, and inflammatory signal in the Thbs1−/− macrophages 34. More recently, Csányi et al showed that TSP1, through its interaction with CD47, stimulates production of reactive oxygen species and attenuates vasodilatation 35. Conversely, in the retina, TSP1 mediates pro-inflammatory microglia such that a lack of TSP1 is associated with a spontaneous increase in inflammatory mediators 36. Further, TSP1 is involved in the maintenance of the immune privileged status of the ocular region 37.

TSP1 is present at low levels in the wall of healthy blood vessels, and its vascular expression is upregulated in animal models of atherosclerosis and ischemia-reperfusion injury 33, 38. In general, high plasma TSP1 levels correlate positively with cardiovascular disease 39, however, serum levels of TSP1were reported to be negatively associated with AAA 40. These findings are not necessarily contradictory nor definitive of any one disease state, as plasma and serum concentrations of TSP1 are sensitive to platelet number in the blood, platelet content of TSP1, and proportion of TSP1 released from platelets during preparation of plasma or serum 41. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the role of TSP1 in vascular inflammation and aneurysm pathogenesis through the use of two chemically-induced AAA models using Thbs1−/− mice. The results presented here show that TSP1 expression is required for macrophage adhesion to ECM proteins, migration toward chemokines, and recruitment to the vascular wall during AAA formation.

METHODS

The detailed methods are shown in online supplements.

RESULTS

Levels of TSP1 are elevated in aneurysmal aorta

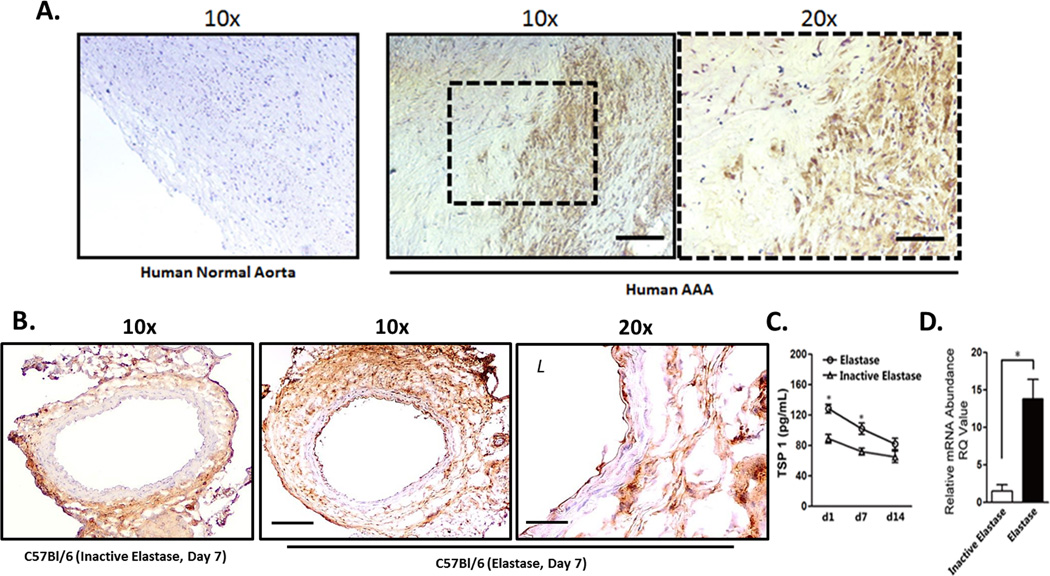

Expression of TSP1 was evaluated in human aortic tissues using an anti-TSP1 antibody for immunohistochemical analysis. Compared to normal aortas, aneurysmal tissues displayed higher levels of TSP1 throughout the aortic wall (Fig. 1A). In order to evaluate the potential role for TSP1 in the development of aneurysm, we turned to murine models of the disease. First, we utilized the elastase-induced model of murine aneurysm, created by the brief perfusion of porcine pancreatic elastase (or equal concentration of heat-inactivated elastase) through the infrarenal region of the abdominal aorta. Following aneurysm induction, C57BL/6 male mice were harvested at various time points to evaluate TSP1 expression and aneurysmal features. In accordance with the established model, elastase perfusion produced gradual aortic dilation associated with elastin fragmentation and aortic inflammation (Supplemental Figure I). Immunohistochemical staining revealed a significantly higher expression of TSP1 in the elastase-treated aortas compared to inactivated elastase-treated controls (Fig. 1B). The upregulation of TSP1 was most noticeable in the adventitia, an area known to be subject to macrophage accumulation 42–44. Using an ELISA-based assay, we confirmed that elastase-treated aortic tissues contained a significantly higher level of TSP1 than inactive-elastase treated tissues, and that this difference occurred rapidly after surgery and declined over time (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, RT-PCR analysis revealed that elastase-treatment induced >4-fold increase in the level of Thbs1 mRNA in the aortic wall 3 days after surgery (Figure 1D). Co-immunostaining study in mouse aneurysm tissue revealed that CD68+ macrophages cluster in regions of the artery that are also positive for TSP1, and that TSP1 did not appear to co-localize with smooth muscle cells (myosin heavy chain 11, MHC) or neutrophils (myeloperoxidase, MPO) (Supplemental Figure II). Immunohistochemical analysis showed a similar upregulation of TSP1 in aneurysmal tissues harvested from ApoE−/− mice treated with Angiotensin II (Supplemental Figure IIIA) or in C57BL/6 mice treated with CaPO4 (Supplemental Figure IIIB).

Figure 1. Thrombospondin 1 (TSP1) expression is increased in human and experimental aneurysm.

(A) Non-aneurysmal (Normal) and aneurysmal (AAA) human abdominal aorta stained for TSP1. Scale bar 200µm (10x) and 100µm (20x). (B) Experimental aneurysm tissues harvested from C57BL/6 mice 7 days after inactive elastase (control) or elastase treatment, stained for TSP1. Scale bar 200µm (10x) and 100µm (20x). (C) TSP1 expression as measured by ELISA at days 1 (d1), 7 (d7), and 14 (d14) after treatment with elastase (open circle) or inactive elastase (open triangle). (D) Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) results for TSP1 expression in the aortic wall 7 days after surgery. *p<0.05.

Mice deficient in Thbs1 are resistant to AAA induction

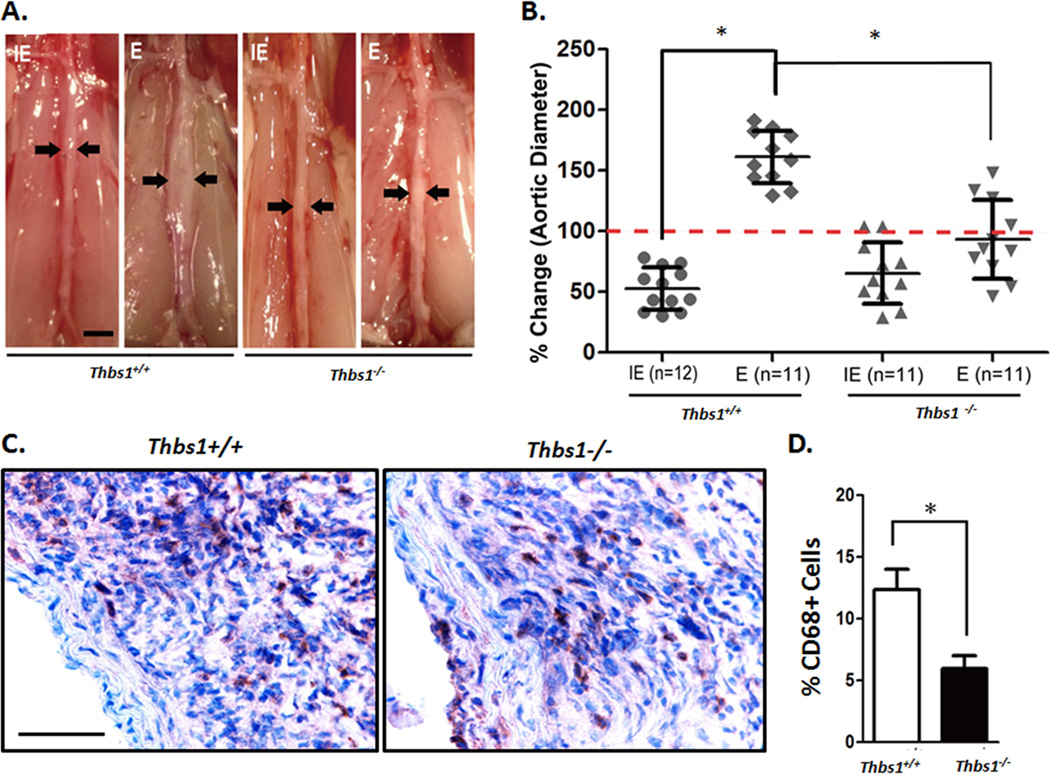

To determine whether TSP1 contributes to aneurysm pathogenesis, we subjected Thrombospondin-1 deficient (Thbs1−/−) mice to aneurysm induction by either the elastase or CaPO4 model. Prior to aneurysm induction, the basic structure of the aortic wall of Thbs1−/− and wildtype mice appeared similar and contained comparable levels of Thrombospondin-2, the closest homolog within the TSP family to TSP1 26 (Supplemental Figure IV). Following aneurysm induction by elastase and CaPO4 aneurysm models, aortas harvested from Thbs1−/− mice displayed marked decreases in inflammatory responses and aortic dilation when compared to the aneurysmal responses seen in wildtype (Thbs1+/+) mice (Figure 2A, B and Supplemental Figure VA, B). In the elastase model, only 4 out of the 11 Thbs1−/− mice developed aneurysm, whereas all Thbs1+/+ mice developed aneurysm, defined as a 100% or larger increase in aortic diameter (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the 4 Thbs1−/− animals that developed aneurysm following elastase treatment displayed significantly smaller aortic expansion than the Thbs1+/+ mice (diameter increases 93.2±31% and 153.4±45.4% in Thbs1−/− and Thbs1+/+, respectively). In the CaPO4 model, none of the 7 Thbs1−/− mice developed aneurysmal dilation, as compared to 9 out of 10 Thbs1+/+ mice that developed aneurysm (diameter increases 67.9±17.9% and 119.4±32.3% in Thbs1−/− and Thbs1+/+, respectively) (Supplemental Figure VB).

Figure 2. Thbs1−/− mice are resistant to aneurysm induction.

(A) Representative images of wildtype (Thbs1+/+) and Thbs1−/− arteries 14 days after treatment with inactive elastase (IE) or elastase (E). Scale bar 2mm. (B) Graphic depiction of aortic dilation (%Change in aortic diameter) in IE- (circle) or E- (diamond) treated Thbs1+/+ arteries and IE- (triangle) or E- (wedge) treated Thbs1−/− arteries. Red dotted line designates aneurysmal formation (100% change in aortic diameter); *p<0.05 as compared to E-treated Thbs1+/+. (C) Representative images of immunohistochemical stains for macrophages (CD68) in elastase treated arteries. Scale bar 100µm. (D) Quantification of macrophage infiltration, shown as % Positive Cells ((CD68+/nuclei)*100). *p<0.05.

Inflammation is diminished in aneurysms of Thbs1−/− animals

Transmural infiltration of inflammatory cells, predominantly macrophages, is a major histological characteristic of aneurysm 5, 17, 42, 45. Elastase- or CaPO4-induced aneurysmal tissues harvested from Thbs1+/+ mice displayed a significant infiltration of monocytes and macrophages, consistent with features of the models as reported in previous literature 6, 46(Figure 2C, D and Supplemental Figure VC). Conversely, aortic samples harvested from Thbs1−/− mice treated either with elastase or CaPO4 contained significantly fewer macrophages measured by the aortic accumulation of CD68 positive cells (12.3±1.4% in Thbs1+/+ vs. 5.9±0.7% in Thbs1−/− in elastase treated tissues, Figure 2C, D; 9.7±1.2% in Thbs1+/+ vs. 4.2±0.6% in Thbs1−/− sections following CaPO4 treatment, Supplemental Figure VC). In alignment with diminished aortic dilation and macrophage infiltration, Thbs1−/− aortas displayed attenuated elastin degradation as compared to the Thbs1+/+ counterparts (Supplemental Figure VD).

The diminished inflammatory response caused by the lack of TSP1 was confirmed by decreased number of MOMA2 positive cells, which represent monocytes and macrophages (Supplemental Figure VI). Furthermore, following elastase treatment, the lack of TSP1 was associated with reduced infiltration of neutrophils (NIMP-R14 positive) by nearly 3-fold in elastase-treated tissues (18.7±5.9% of total cells in Thbs1+/+ animals compared to 6.1±2.5% of total cells in Thbs1−/−). However, T lymphocyte (CD3 positive) infiltration was not significantly changed between the two genotypes (Supplemental Figure VI). Immunohistochemical staining showed that IL-6 expression was reduced in Thbs1−/− arteries. MCP-1, a chemokine known to be critical for monocyte/macrophage recruitment during aneurysm development, appeared to be similarly upregulated in the tunica media of both genotypes (Supplemental Figure VII), although the adventitial accumulation of MCP-1 appeared to be reduced by TSP1gene deficiency, likely due to the diminished presence of macrophages in the knockouts. Since TSP1 can activate TGFβ, we evaluated the TGFβ activity in the aortic wall following aneurysm induction by immunostaining for phosphorylated Smad3. Elastase treatment increased levels of Smad3 phosphorylation as compared to inactive elastase control, but differences between Thbs1−/− and Thbs1+/+ mice were insignificant (Supplemental Figure VIIIA, B).

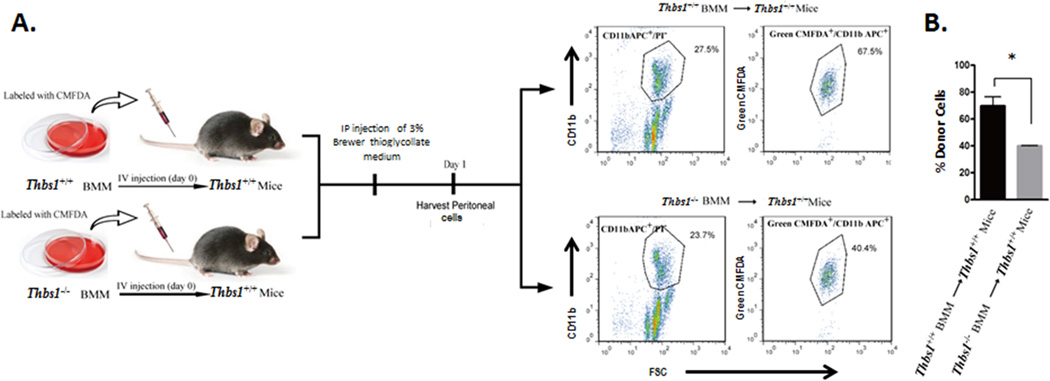

TSP1 is necessary for optimal mobility of monocytic cells

The immunohistochemical evidence provided above suggests that the reduction in monocyte and macrophages found in aneurysmal Thbs1−/− aortas cannot be attributed simply to the cytokine milieu in these tissues. Thus, to determine which of the step(s) in the inflammatory response is affected by Thbs1 deficiency, we cultured monocytic cells from the bone marrow of Thbs1−/− and Thbs1+/+ mice. The bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMM) were labeled ex vivo with the fluorescent dye CMFDA and injected via the tail vein into Thbs1+/+ host mice. The host mice were then given an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of thioglycollate (Figure 3A). Twenty-four hours after thioglycollate injection, peritoneal cells were isolated and CMFDA-positive cells (donor monocytes) in CD11b (a monocyte/macrophage marker)-positive populations were identified by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 3B, only 39.9±0.2% of the CD11b positive peritoneal-derived inflammatory cells were positive for CMFDA when Thbs1−/− BMM were used as donors as compared to 69.7±4.0% when Thbs1+/+ BMM were used, suggesting a compromised mobility of Thbs1−/− BMM.

Figure 3. Thbs1−/− bone marrow mononuclear cells demonstrate reduced tissue infiltration capability in vivo.

(A) Schematic of experimental design. From left: fluorescence (CMFDA)-labeled bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMM) from Thbs1−/− or Thbs1+/+ mice were injected via tail vein to Thbs1+/+ mice, followed by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of thioglycollate. Peritoneal cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for live monocytes (CD11b APC+/PI−). Donor BMM was identified by CMFDA (Green CMFDA+). (B) Quantification of donor-derived infiltrating monocytes shown as %Donor Cells (number of Green CMFDA+ cells/number of CD11b APC+/PI− cells). *p<0.05.

Adoptive transfer of Thbs1+/+ bone marrow monocytic cells reverses the aneurysm-resistant phenotype of Thbs1−/− mice

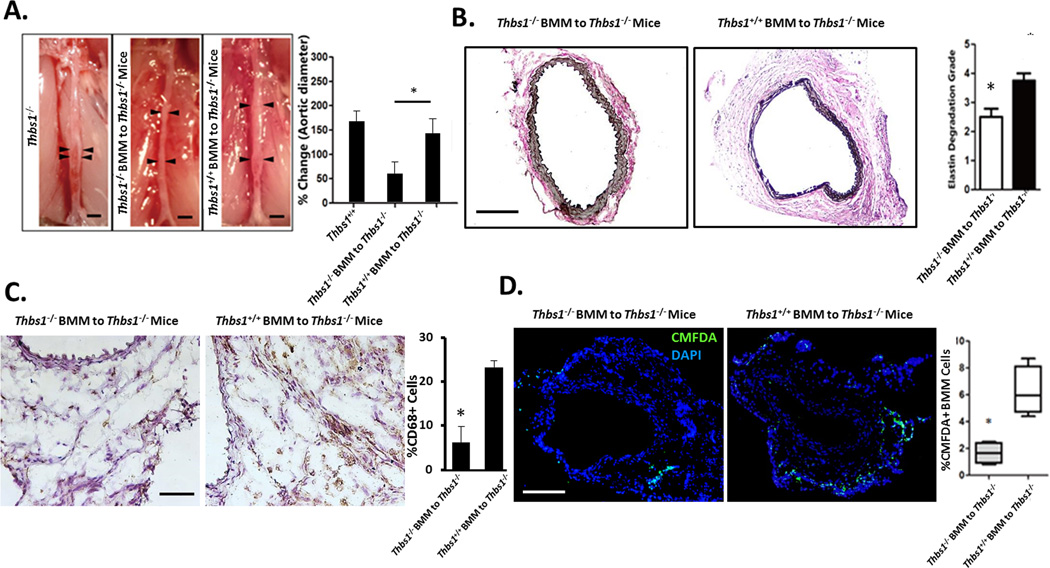

To test whether the migratory defect of Thbs1−/− BMM is responsible for the aneurysm resistance of Thbs1−/− mice, CMFDA-labeled Thbs1+/+ BMM were adoptively transferred to Thbs1−/− mice every three days starting 1 day after the aneurysm induction (Supplemental Figure IX). As a control, CMFDA-labeled Thbs1−/− BMM was similarly administered to Thbs1−/− mice. Both groups of mice were sacrificed 14 days after elastase perfusion and analyzed for aortic dilation, inflammation, and elastin degradation. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, Thbs1−/− mice that received Thbs1−/− BMM failed to develop aneurysm (57.2 ±23.1% diameter increase). In contrast, the mutant mice that received Thbs1+/+ BMM developed an aneurysmal dilation that was not statistically different from what was observed in Thbs1+/+ mice (138.1 29.3% vs. 162.6 19.6% diameter increase, respectively). Histologically, the Thbs1−/− mice receiving Thbs1+/+ BMM responded to aneurysm induction with elastin degradation, which was absent in those mice that were transferred with Thbs1−/− BMM (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the transfer of Thbs1+/+ BMM to Thbs1−/− mice restored the infiltration of macrophages (CD68+) to numbers similar to those seen in Thbs1+/+ arteries (Fig. 4C). Fluorescent microscopy confirmed the vascular recruitment of the transferred Thbs1+/+ BMM (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these data suggest that inflammatory signals are intact in the aortic wall of Thbs1−/− mice, and that supplementing these mutant animals with exogenous Thbs1+/+ BMM can therefore restore the inflammatory response and other aneurysmal phenotypes.

Figure 4. Thbs1+/+ bone marrow mononuclear cells restore aneurysm phenotype in Thbs1−/− mice.

(A) Schematic of experimental design. Aneurysm was induced at day 0 (Elastase, red arrow). BMM cells were injected on days 1, 4, 7, and 10. Sacrifice and analysis was carried out on day 14 (red arrow). (B) Representative images of arteries at sacrifice, scale bar 2mm. Graphic representation of aortic expansion is shown at right. (C) Representative images of arterial cross sections stained with Van Giesson to demonstrate elastin fragmentation, scale bar 200µm. Semi-quantification of elastin fragmentation is shown on the right. (D) Representative images of immunohistochemical stains for macrophages (CD68+). Scale bar 100µm, inlaid image 10x. Number of infiltrating macrophages were counted and expressed as %Positive Cells ((CD68+/nuclei)*100. (E) Representative images of CMFDA-labeled donor cells (green) infiltrated to elastase-treated arteries, nuclei identified by DAPI (blue). Scale bar 200µm. Quantification of infiltrated donor-derived cells, expressed as %Positive Cells (fluorescent cells/nuclei), is shown on the right. *p<0.05.

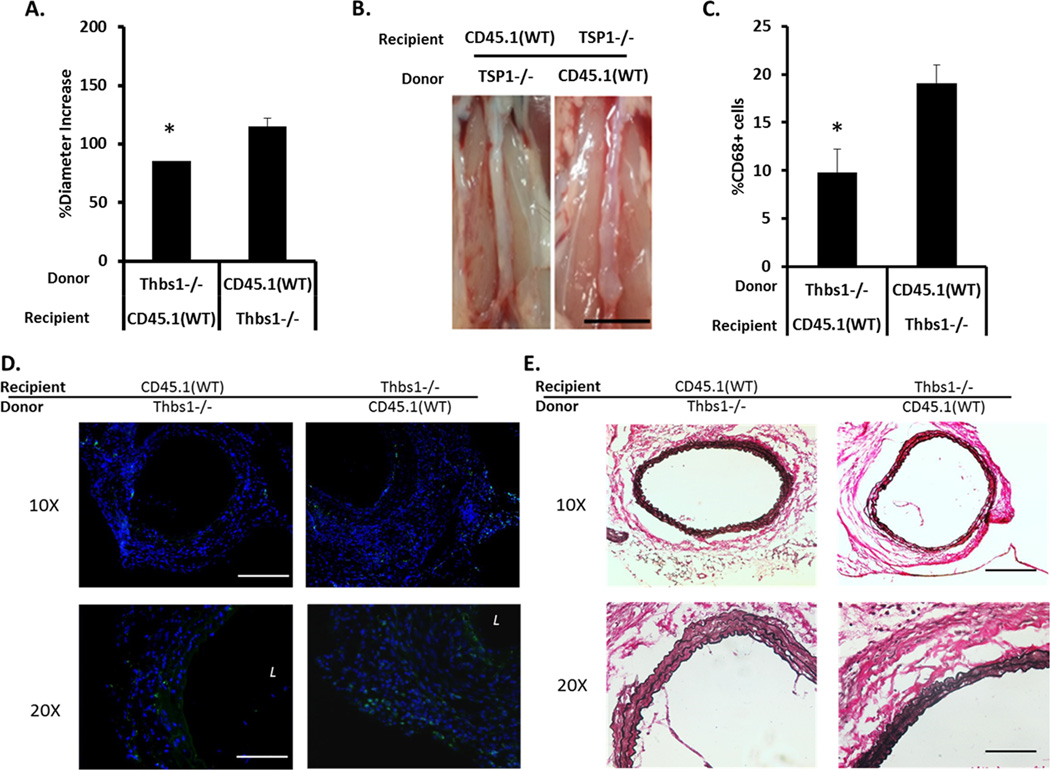

Thbs1 gene deficiency in bone marrow cells dictates aneurysm resistance

To further elucidate the importance of TSP1 in circulating inflammatory cells, we conducted bone marrow transplantations between Thbs1 knockout and wildtype. Since Thbs1−/− mice were in C57B/6 background and express CD45.2, we used a substrain of C57B/6 expressing the CD45.1 allele (C57B/6-CD45.1) as the wildtype for easy monitoring (Supplemental Figure X). Six weeks after bone marrow transplant, recipient mice with confirmed bone marrow reconstitution determined by flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood, were subjected to aneurysm induction using the elastase model. Aortic expansion as well as aneurysm-associated pathology was measured fourteen days after aneurysm induction. As shown in Figure 5A, transplantation of Thbs1−/− bone marrow cells to the wildtype mice (knockout → wildtype) inhibited aneurysm formation, producing an aortic expansion measuring 85.8±7.5%. In contrast, transplantation of Thbs1−/− mice with the wildtype bone marrow (wildtype → knockout) developed aneurysm (114.9±13.1% increase in aortic diameter) (Figure 5A, B). The transplant procedure itself does not alter the aneurysm phenotype because the control groups, wildtype → wildtype or knockout → knockout, responded to aneurysm induction similar to the wildtype or knockout mice without bone marrow transplant (Supplemental Figure XI). Histological analyses revealed that the aneurysmal characteristics, i.e. elastin degradation and monocyte/macrophage infiltration, were dictated by the Thbs1 genotype of the bone marrow (Figure 5C–E).

Figure 5. Thbs1 gene deficiency in bone marrow cells dictates aneurysm formation.

Results of a bone marrow chimera model with C57B/6-CD45.1 wildtype (CD45.1(WT)) and Thbs1 knockout (Thbs1−/−) mice. (A) Graphic representation of aneurysm expansion 14 days after elastase-induced aneurysm.; *p<0.05. (B) Representative images of arterial expansion at the time of expansion measurement; scale bar = 5mm. (C) Quantitative evaluation of macrophage (CD68+) infiltration; *p<0.05. (D) Representative images of macrophage (CD68+) infiltration, counterstain with DAPI (blue). L indicates lumen. (E) Representative elastin stains. Scale bar= 200um in 10x images, 100um in 20x images.

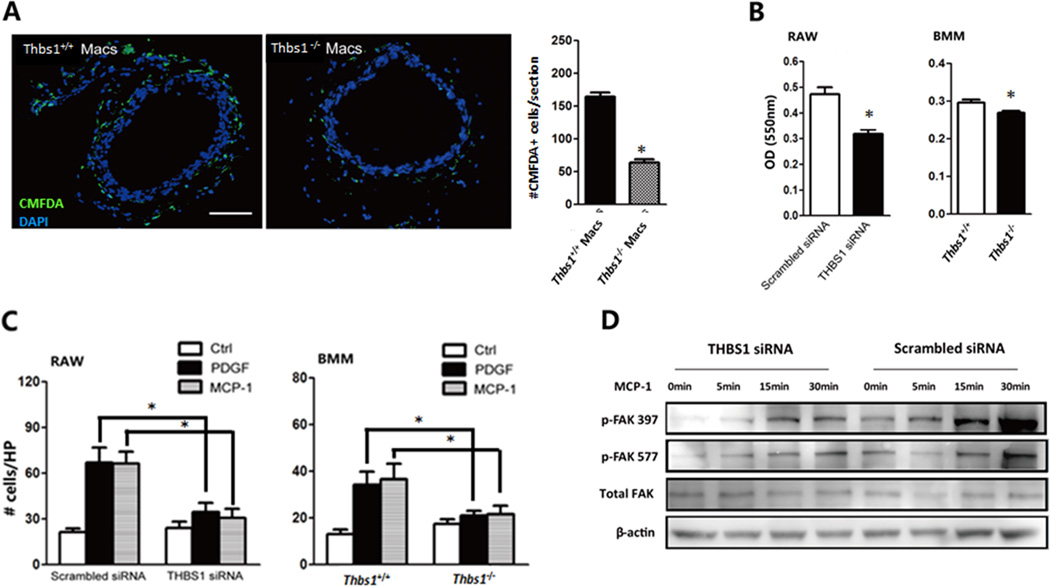

TSP1 is required for optimal adhesion and migration of monocytic cells

Next, we examined whether Thbs1 gene deficiency affects the ability of macrophages to adhere to matrix proteins in an ex vivo adhesion assay. Aortic rings were prepared from Thbs1+/+ mice 3 days after aneurysm induction with elastase and incubated with CMFDA-labeled peritoneal macrophages from Thbs1+/+ or Thbs1−/− mice. The number of Thbs1−/− macrophages that adhered to the aortic tissues was 62% less than that of the Thbs1+/+ macrophages (Fig. 6A). Similarly, Thbs1−/− BMM showed reduced adhesion to fibronectin in an in vitro culture system (Fig. 6B). To exclude a possible indirect effect of embryonic gene deletion, we transiently silenced Thbs1 expression in RAW264.7 cells using an siRNA specific to TSP1. Compared to a scramble control, Thbs1 siRNA attenuated RAW264.7 cell adhesion by 33% (Fig. 6B). In a transwell migration assay, inhibition of TSP1 expression via gene deletion or siRNA completely abolished the ability of BMM or RAW264.7 cells to migrate toward chemokines (PDGF-BB or MCP-1) (Fig. 6C). Additionally, MCP-1-induced cellular adhesion, represented here by elevation of tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (p-FAK 397 and 577), was diminished by Thbs1 gene silencing in RAW264.7 (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. Monocytes/macrophages lacking TSP1 display reduced adhesion and migration capability.

(A) Thbs1+/+ aortic rings were incubated with CMFDA-labeled (green) peritoneal macrophages (Macs), nuclei labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar 200µm. Adhered CMFDA+ Macs from Thbs1+/+ (black) or Thbs1−/− (white) mice were counted and expressed as # cells/section. (B) in vitro adhesion assay on fibronectin-coated surface; graph at left showing RAW264.7 (RAW) cells treated with TSP1-specific siRNA (THBS1 siRNA, black bar) or scramble control (white bar), graph at right showing bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMM) harvested from Thbs1+/+ (white bar) or Thbs1−/− (black bar) mice. (C) Chemotaxis toward PDGF (black) or MCP-1 (grey) or solvent (white) was assessed for RAW cells treated with scramble siRNA or TSP1-specific siRNA (THBS1 siRNA) (left graph) or BMM harvested from Thbs1+/+ or Thbs1−/− mice (right graph). Results shown as number of migrated cells per high power field (HP). (D) Western blot measurement of phosphorylated (p-FAK) and total focal adhesion kinase (Total FAK) following administration of MCP1 in RAW264.7 cells after TSP1 knockdown (THBS1 siRNA) or scrambled siRNA control. β-actin used as loading control. *p<0.05.

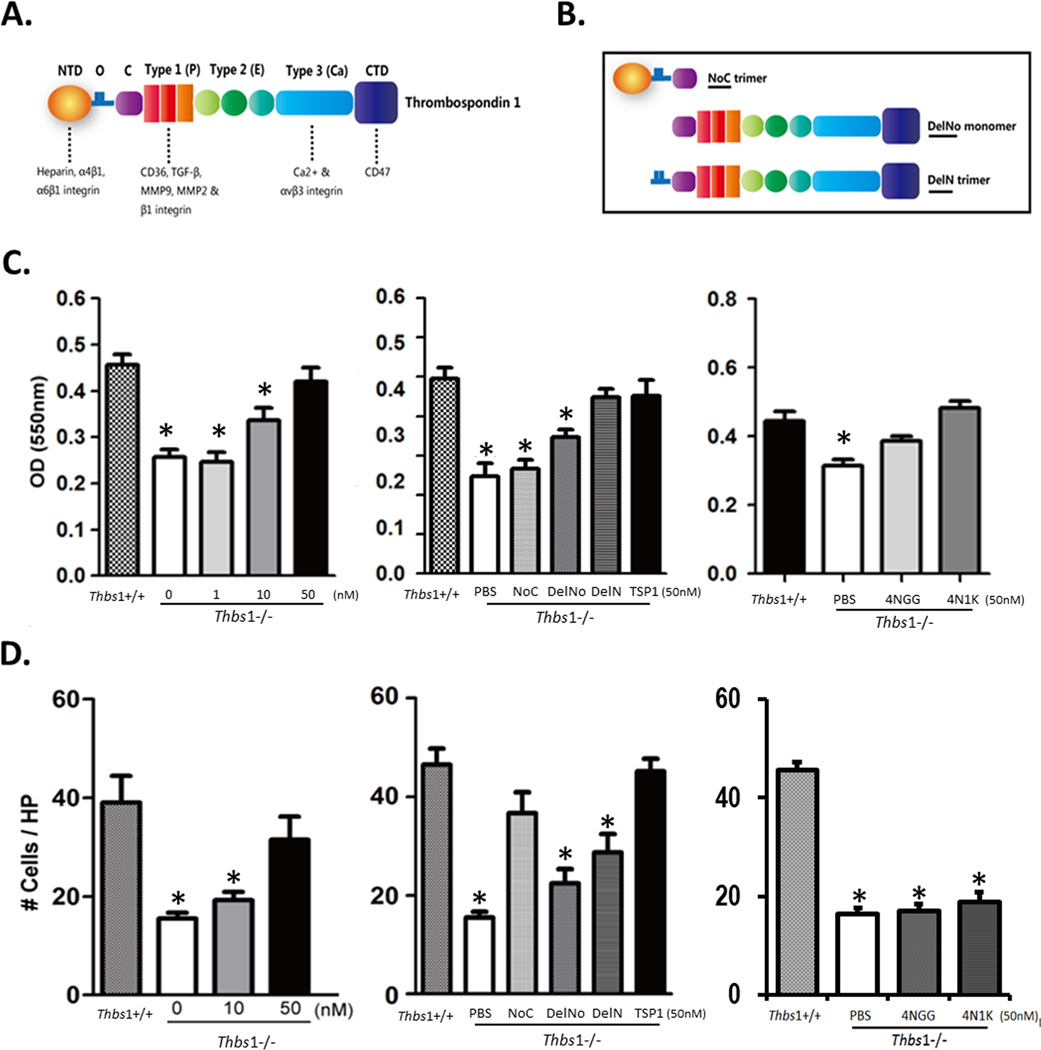

The adhesive and migratory defects of Thbs1−/− monocytic cells are rescued by recombinant TSP1

The TSP1 molecule contains various domains that interact with matrix proteins, integrins, CD36, CD47, or other protein factors (Fig. 7A). We attempted to restore the ability of Thbs1−/− macrophages to adhere and/or migrate by supplementing them with recombinant TSP1 and to map the active region(s) of TSP1 with constructs comprising various domains within the TSP1 molecule (Figure 7B). Using fibronectin as an adhesion substrate, we demonstrated that recombinant TSP1 dose-dependently restored adhesion of BMM isolated from Thbs1−/− mice (Fig. 7C). In fact, in the presence of 50nM recombinant TSP1, Thbs1−/− BMM demonstrated no functional differences from Thbs1+/+ BMM in this in vitro adhesion assay. This same adhesion assay was performed using various TSP1 domain constructs containing or lacking the oligomerization domain that results in trimer formation. The N-terminal domain (NTD) trimer, (NoC), and the C terminal domain (CTD) monomer (DelNo) failed to rescue adhesion of Thbs1−/− BMM. However, the CTD trimer (DelN) restored adhesion of Thbs1−/− BMM, similar to the restoration obtained with whole TSP1. DelN contains 3 copies of the module that engages CD47. Next, we examined the specific effects of the CD47-binding domain through the administration of the 4N1K peptide (50nM), a CD47 agonist. 4N1K successfully restored adhesion of Thbs1−/− BMM to fibronectin. The 4NGG control peptide also produced a moderate, but significant, increase in adhesion. However, the 4N1K peptide fully restored Thbs1−/− BMM adhesion to the level of Thbs1+/+ macrophages, and to a more significant degree than control 4NGG peptide (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Rescuing adhesion and migration of Thbs1−/− BMM with exogenous TSP1 protein or fragments of TSP1 molecule.

(A) Cartoon representation of the TSP1 molecule, its domains and receptors. N-terminal domain (NTD), oligomerization sequence (O), procollagen molecule (C), properdin repeat (Type 1 (P)), EGF-like repeat (Type 2 (E)), calcium repeats (Type 3 (Ca)), C-terminal domain (CTD). Domain receptors indicated beneath the image. (B) Cartoon depiction of TSP1 fragments. (C) In vitro adhesion assay on fibronectin-coated plates using bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMM) from Thbs1+/+ or Thbs1−/− mice quantified by optical density (OD) of adhered cells. (left) Rescue with recombinant TSP1 (0, 1, 10, 50nM). *p<0.05 compared to wildtype (Thbs1+/+). (center) Thbs1−/− BMM supplemented with solvent control (PBS), TSP1 fragments NoC, DelNo, DelN, or whole TSP1 (TSP1). *p<0.05 compared to wildtype (Thbs1+/+). (right) Rescue with CD47-binding domain peptide 4N1K or control peptide 4NGG compared to solvent (PBS). *p<0.05 compared to wildtype (Thbs1+/+). (D) In vitro chemotaxis toward MCP-1 using BMM from Thbs1+/+ and Thbs1−/− mice, quantified as migrated cells counted per high power field (HP). (left) Rescue with recombinant TSP1 (0, 1, 10, 50nM). *p<0.05 compared to wildtype (Thbs1+/+). (center) Thbs1−/− BMM supplemented with PBS, TSP1 fragments NoC, DelNo, DelN, or TSP1. *p<0.05 compared to wildtype (Thbs1+/+). (right) Rescue with CD47-binding domain peptide 4N1K or control peptide 4NGG compared to solvent (PBS). *p<0.05 compared to wildtype (Thbs1+/+).

Recombinant TSP1 also dose-dependently rescued the chemotactic capability of Thbs1−/− BMM in an MCP-1-stimulated migration assay (Fig. 7D). In contrast to the results in the adhesion assay, administration of either monomeric DelNo or trimeric DelN successfully restored migration of Thbs1−/− BMM toward MCP-1. 4NIK and its control 4NGG peptides did not alter the inhibited migration of Thbs1−/− BMM. One of the mechanisms by which TSP1 is expected to influence inflammation is through the activation of TGFβ 30. Using an MCP-1-driven transwell migration assay, we evaluated the migratory capacity of Thbs1+/+ or Thbs1−/− peritoneal macrophages in the presence or absence of supplemental TGFβ (5ng/mL). Similar to what we showed above with BMM cells, Thbs1−/− peritoneal macrophages migrated less efficiently as compared to Thbs1+/+ peritoneal macrophages (Supplemental Figure VIIIC). Administration of TGFβ did not restore the migratory capacity of Thbs1−/− peritoneal macrophages. In fact, TGFβ significantly reduced migration of peritoneal macrophages of both genotypes, albeit more profoundly in the wildtype (Supplemental Figure VIIIC).

DISCUSSION

The present work explored, for the first time, the role of TSP1 in aneurysm pathophysiology using three established murine models of abdominal aortic aneurysm. TSP1 accumulation was notably increased in aneurysmal tissues, particularly adventitia, following either elastase perfusion or CaPO4 application in C57BL/6 mice or following angiotensin II infusion in ApoE−/− mice. Histological and morphological examinations of elastase- or CaPO4-treated tissues harvested from Thbs1−/− mice showed a profound reduction in the characteristic features of aneurysm including inflammation, disruption of elastin fibers, and aortic dilation. This aneurysm-resistant phenotype was “rescued” by adoptive transfer of the Thbs1+/+ mononuclear cells isolated from the bone marrow. These results are a striking example of uncovering the importance of a matricellular protein by stressing an organ and define a direct role for TSP1 in regulating mobility of monocytic cells, at least in the aneurysm setting.

Many cell types within the aortic wall including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and adventitial fibroblasts are capable of expressing TSP1 47, 48. After aneurysm induction, TSP1 appeared to be more prominent in the adventitia and intima. As a potent anti-angiogenic factor, TSP1 inhibits endothelial cell proliferation 49, 50 and migration 28, 51 and induces apoptosis 52, 53. In vascular SMCs, TSP1 has been shown to promote proliferation and migration 54. These diverse functions of TSP1 may differentially affect how the aortic wall responds to injuries associated with aneurysm. In the elastase-induced AAA model, reconstitution of wildtype mice with Thbs1−/− bone marrow cells inhibited aneurysm formation. Thbs1+/+ inflammatory cells, whether delivered through bone marrow transplant or adoptive transfer, rescued aneurysm development in Thbs1−/− mice. However, the aneurysm restoration was not 100% suggesting that the role for TSP1 is not entirely restricted to monocytic cells. Future studies are necessary to elucidate how TSP1 derived from mesenchymal cells (such as SMC) contributes to aneurysm pathogenesis.

It has been recently demonstrated that TSP1 stimulates reactive oxygen species production in vascular SMCs through a direct TSP1/CD47-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase 1 9. While oxidative stress has been well linked as an underlying pathogenic player in abdominal aortic aneurysm 5, our results from the adoptive transfer and ex vivo adhesion studies suggest that the reduction in inflammation protection is primarily caused by the reduced ability of Thbs1−/− monocytes to migrate toward injured aorta. TSP1 was most prominently expressed in the adventitia of aneurysmal tissue, where infiltrating monocytes and macrophages accumulate. In contrast, the highest MCP-1 signal was detected in the aortic media. Thbs1 gene deficiency did not alter the medial MCP-1 accumulation nor apoptosis of vascular SMCs (data not shown), two well-established processes resulting from aneurysm induction 44, 45, 55, 56.

Elevated levels of TSP1 in the vessel wall are observed in several other cardiovascular disorders including diabetes mellitus 57, atherosclerosis 58, 59, and ischemia-reperfusion injury 38, 60. TSP1 has been shown to have opposing roles within diseases and/or disease models, indicating that this highly complex molecule may interact with other factors and/or act dependent upon tissue types and/or diseases. For example, in a cardiac infarct model TSP1 expression appeared to confine the area of injury61, whereas overexpression of TSP1 was found to negatively impact wound healing and vascularization in a wound healing model62. Early reports demonstrated that one characteristic of Thbs1−/− mice was a consistent and significant pulmonary inflammatory state63. Adding to the contradictory evidence regarding TSP1 was a report that Thbs1 deficiency correlated with increased leukocyte and macrophage infiltration to mature plaques in Thbs1 and ApoE double knockout mice 33. The authors attributed this pro-inflammatory phenotype to the diminished phagocytic ability of macrophages 33. Our data demonstrate that TSP1 is one of the factors that differentiate aneurysm and atherosclerosis mechanistically, although many AAA patients are also diagnosed for atherosclerosis. Previous publications have revealed additional differentiating factors between these two diseases, such as the chemokine CXCL10 64 and the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ 65. Findings such as these further our understanding of the two diseases and may permit the identification of therapeutic targets. Further, various disease states are significantly impacted by the type and/or source of macrophages present in the tissue. 66, 67 While our study has not explored this concept thoroughly, we are tempted to speculate that the TSP1-dependent migration of bone marrow derived monocytes/macrophages is a significant contributor of inflammatory state associated with AAA.

Our in vitro rescue studies indicate that TSP1 promotes monocytic cell adhesion to ECM by multivalent binding to the C-terminal cell binding domain (CBD) where CD47 binds 68. CD47 was initially identified for its association with αvβ3 integrin, and ligation of this transmembrane protein either through its natural ligand TSP or monoclonal antibodies recapitulate a series of cellular functions including adhesion, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis 69. Although previous reports have shown that the TSP1/CD47 interaction differentially modulates migration and/or adhesion, these varying results are suggested to depend upon the functional fragment of TSP1 that is most highly expressed in a biological situation 70. Interestingly, our findings suggest that the CD47-binding capability of TSP1alone is not sufficient for the migration of monocytic cells in this setting, as the CD47 agonist peptide 4N1K did not significantly change the migration response of Thbs1−/− BMM toward MCP-1. However, the two TSP1 constructs containing the CD47-binding domain as well as Type 1–3 repeats successfully restored migration in Thbs1−/− BMM. In a related study, the integrins αMβ2 and β3 were found to be critical to the adhesive and migratory capability of macrophages71. While the study by Frolova et al. focuses on TSP4, TSP1 and TSP4 share multiple features of their C-terminal regions reinforcing the importance of this segment. Further investigation will be required to better understand how the unique AAA environment influences these interactions.

Twenty years ago, TSP1 was reported to promote chemotaxis of human peripheral blood monocytes 72. This chemotactic function is believed to promote monocyte migration to the site of injury where TSP1 is upregulated. However, this chemotactic function seems to be less important in aneurysm pathophysiology. Interestingly, Thbs1−/− arteries were able to recruit normal (Thbs1+/+) monocytic cells, as evidenced by adoptive transfer and bone marrow transplant studies. A potential explanation is that there are redundant pro-inflammatory chemoattractant signals produced by the injured aorta which is not dependent on TSP1. For example, MCP-1 production by injured SMCs has been shown to be important for aneurysm-associated inflammation 55, 73, 74. However, knocking out MCP-1 (also called CCL2) has limited impact on aneurysm development, whereas knocking out its receptor, CCR2, significantly reduces aneurysm expansion 42, 45, 73, indicating a more complex role for CCL1/CCR2 signaling in aneurysm development. The co-localization between TSP1 accumulation and macrophages suggests that the elevated TSP1 is likely a result of inflammatory cell recruitment (i.e. is produced by infiltrating inflammatory cells). In the context of aneurysm, the primary function of TSP1 in inflammation is through regulation of adhesion and migration of monocytic cells. Again, this assertion is supported by the successful restoration of aneurysm by bone marrow transplant of Thbs1−/− to Thbs1+/+ recipients.

A potential mechanism by which TSP1 may affect inflammation is activation of TGFβ. However, TSP1 exerts its role in tissue repair via both TGFβ-dependent and independent mechanisms 75. In the case of atherosclerosis, the increased inflammation in the absence of TSP1 was found to be independent of TGFβ activation 33. Similarly, we found mice of both genotypes responded to aneurysm induction with comparable levels of Smad3 phosphorylation detected in the aortic tissues. We believe that TSP1 modulates aneurysm associated inflammation primarily through a TGFβ-independent mechanism. This notion is further supported by our in vitro study in which TGFβ failed to restore the migratory defect of Thbs1−/− BMM.

In summary, we conclude that TSP1 plays a key role in regulation of macrophage adhesion, migration, and recruitment in the inflammatory response during pathogenesis of AAA in mice. While murine models of AAA do not resemble the etiology of human aneurysm, these models reproduce the major pathological characteristics of the human disease including macrophage-mediated inflammation 6. However, the relationships between the models and the human disease are an important consideration. In our study, elastase perfusion induces an acute inflammatory response that culminates in aneurysm formation while the initiating and perpetuating events in the human condition are largely unknown. The relatively high level of TSP1 observed on day 1 following elastase perfusion may reflect this acute inflammatory response. Although the protective effect of Thbs1 gene deficiency in two distinct models of AAA is encouraging, significant work remains to be done regarding the role of TSP1 in human AAA. Despite this shortcoming, the current work underscores the importance of TSP1 in the recruitment of monocytic cells in the context of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Since many TSP1-derived activating/inhibitory peptides have been described and shown to be active in vivo, we will explore in the future whether manipulation of TSP1 functions would alter aneurysm formation in the Thbs1-deficient mice and more importantly in mice with existing aneurysm. Interestingly, a TSP1 antagonist peptide was shown to promote aneurysm expansion in established angiotensin II-induced aneurysms through the attenuation of TGFβ1 activation76. Although the unaltered TGFβ signaling within the aortic wall shown in this paper suggests that the lack of TSP1 affects abdominal aortic aneurysm through non-TGFβ related functions of this matricellular protein, the study by Krishna et al. proved the feasibility of modifying aneurysm pathophysiology through tweaking TSP1 functions with peptides.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is characterized by an inflammatory response dominated by macrophages.

Thrombospondin 1 (TSP1) is a matricellular protein that regulates multiple biological functions including cell proliferation and adhesion and angiogenesis.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

-

Levels of TSP1 are elevated in human and mouse aneurysmal tissues.

TSP1, primarily in monocytes and macrophages, is critical for vascular inflammation and aortic expansion in murine models of AAA.

TSP1 promotes monocyte/macrophage adhesion through its C-terminal domain.

This study addresses a knowledge gap regarding the contribution of extracellular proteins in the pathogenesis of aneurysm. We demonstrate a critical role of TSP1 expression, particularly in monocytic cells, in AAA development. Although macrophage infiltration is known to contribute to aneurysm development, the role for TSP1 in this process has not yet been explored. We found that monocytic cells require TSP1 for extracellular matrix adhesion as well as migration, and that aneurysm development is dependent upon this molecule. These findings shed new light on the pathogenesis of AAA and provide new insights into the development of new therapeutic approaches to AAA, for which no effective pharmaceutical treatment currently exists.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Drs. K. Craig Kent and Jon Matsumura of the University of Wisconsin, Madison for intellectual inputs, and Dr. J Lawler at Harvard Medical School for the generous gift of Thbs1 knockout mice.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health R24EY022883 (NS), R01-HL054462 (DM), R01HL088447 (BL), R01CA152108 and R01HL113066 (JZ), American Heart Association 14PRE18560035 (QW), UW-Madison Ophthalmology Core grant P30EY016665 (NS), and an institutional training grant T32 HL110853 (SM).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AAA

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

- SMC

smooth muscle cells

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- TSP1, TSP2

Thrombospondin-1, -2 (protein)

- Thbs1; Thbs1−/−; Thbs1+/+

Thrombospondin-1 (gene); knockout (−/−); wildtype (+/+)

- CD36, CD47, CD11b, CD68, CD3

cluster of differentiation ##

- TGFβ

Transforming Growth Factor beta

- CaPO4

calcium phosphate

- IL6

interleukin-6

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- CMFDA – 5

chloromethylfluorescein diacetate

- BMM

bone marrow mononuclear

- PDGF-BB

platelet derived growth factor, homodimer type BB

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- p- (p-FAK; pSmad3)

phosphorylated-

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- CXCL10

C-X-C motif chemokine 10

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- CBD

cell binding domain

- CCR2/CCL2

CC chemokine receptor/ligand 2

- E/IE

elastase/inactive elastase

- APC

allophycocyanin

- PI

propidium iodide

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- DAPI

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- OD

optical density

- MOMA2

monocyte/macrophage marker 2

- NIMP-R14

anti-neutrophil antibody

- LCCM

L-cell conditioned media

- ANGII

Angiotensin II

- IP

intraperitoneal

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Thrombospondin molecule domain-related terms

- NTD

N-terminal Domain

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- O

oligomerization sequence

- C

pro-collagen molecule

- NoC

N-terminal domain, oligomerization sequence, and procollagen molecule

- DelNo

N-terminal domain and oligomerization sequence deleted

- DelN

N-terminal domain deleted

- P

properdin repeat (Type 1)

- E

epidermal growth factor repeats (Type 2)

- Ca

calcium repeats (Type 3)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diehm N, Dick F, Schaffner T, Schmidli J, Kalka C, Di Santo S, Voelzmann J, Baumgartner I. Novel insight into the pathobiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm and potential future treatment concepts. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;50:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordon IMHR, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Pathophysiology and epidemiology of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2011;8:92–102. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baxter BT, Terrin MC, Dalman RL. Medical management of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2008;117:1883–1889. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.735274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW, Jr, Johnston KW, Krupski WC, Matsumura JS. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms: Report of a subcommittee of the joint council of the american association for vascular surgery and society for vascular surgery. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2003;37:1106–1117. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordon I, Hinchliffe R, Holt P, Loftus I, Thompson M. Review of current theories for abdominal aortic aneurysm pathogenesis. Vascular. 2009;17:253–263. doi: 10.2310/6670.2009.00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Mouse models of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:429–434. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000118013.72016.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rateri DL, Howatt DA, Moorleghen JJ, Charnigo R, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Prolonged infusion of angiotensin ii in apoe−/− mice promotes macrophage recruitment with continued expansion of abdominal aortic aneurysm. The American Journal of Pathology. 2011;179:1542–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun J, Sukhova GK, Yang M, Wolters PJ, MacFarlane LA, Libby P, Sun C, Zhang Y, Liu J, Ennis TL, Knispel R, Xiong W, Thompson RW, Baxter BT, Shi G-P. Mast cells modulate the pathogenesis of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:3359–3368. doi: 10.1172/JCI31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curci JA. Digging in the"soil" of the aorta to understand the growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Vascular. 2009;17:S21–S29. doi: 10.2310/6670.2008.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Li HY, Li H, Zhao J, Su L, Zhang Y, Zhang SL, Miao JY. Lipopolysaccharide activated phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase c and induced il-8 and mcp-1 production in vascular endothelial cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226:1694–1701. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longo GM, Xiong W, Greiner TC, Zhao Y, Fiotti N, Baxter BT. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110:625–632. doi: 10.1172/JCI15334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang T, Xu J, Li D, Chen J, Shen X, Xu F, Teng F, Deng Y, Ma H, Zhang L, Zhang G, Zhang Z, Wu W, Liu X, Yang M, Jiang B, Guo D. Salvianolic acid a a matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibitor of salvia miltiorrhiza, attenuates aortic aneurysm formation in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyo R, Lee JK, Shipley JM, Curci JA, Mao D, Ziporin SJ, Ennis TL, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Thompson RW. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase b) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105:1641–1649. doi: 10.1172/JCI8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deguchi J-o, Huang H, Libby P, Aikawa E, Whittaker P, Sylvan J, Lee RT, Aikawa M. Genetically engineered resistance for mmp collagenases promotes abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in mice infused with angiotensin ii. Lab Invest. 2009;89:315–326. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meijer CA, Stijnen T, Wasser MNJM, Hamming JF, van Bockel JH, Lindeman JHN. Doxycycline for stabilization of abdominal aortic aneurysmsa randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159:815–823. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-12-201312170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baxter BT, Pearce WH, Waltke EA, Littooy FN, Hallett JW, Jr, Kent KC, Upchurch GR, Jr, Chaikof EL, Mills JL, Fleckten B, Longo GM, Lee JK, Thompson RW. Prolonged administration of doxycycline in patients with small asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms: Report of a prospective (phase ii) multicenter study. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:1–12. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.125018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aziz F, Kuivaniemi H. Role of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in preventing abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohoefer F, Reeps C, Lipp C, Rudelius M, Haertl F, Matevossian E, Zernecke A, Eckstein H-H, Pelisek J. Quantitative expression and localization of cysteine and aspartic proteases in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Exp Mol Med. 2014;46:e95. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin Y, Cao X, Yang Y, Shi G-P. Cysteine protease cathepsins and matrix metalloproteinases in the development of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Future Cardiology. 2012;9:89–103. doi: 10.2217/fca.12.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golledge ALV, Walker P, Norman PE, Golledge J. A systematic review of studies examining inflammation associated cytokines in human abdominal aortic aneurysm samples. Disease Markers. 2009;26:181–188. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2009-0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golledge J, Tsao PS, Dalman RL, Norman PE. Circulating markers of abdominal aortic aneurysm presence and progression. Circulation. 2008;118:2382–2392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.802074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimizu K, Mitchell RN, Libby P. Inflammation and cellular immune responses in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:987–994. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000214999.12921.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eliason JL, Hannawa KK, Ailawadi G, Sinha I, Ford JW, Deogracias MP, Roelofs KJ, Woodrum DT, Ennis TL, Henke PK, Stanley JC, Thompson RW, Upchurch GR., Jr Neutrophil depletion inhibits experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation. 2005;112:232–240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J, Sukhova GK, Yang M, Wolters PJ, MacFarlane LA, Libby P, Sun C, Zhang Y, Liu J, Ennis TL, Knispel R, Xiong W, Thompson RW, Baxter BT, Shi GP. Mast cells modulate the pathogenesis of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3359–3368. doi: 10.1172/JCI31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michineau S, Franck G, Wagner-Ballon O, Dai J, Allaire E, Gervais M. Chemokine (c-x-c motif) receptor 4 blockade by amd3100 inhibits experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion through anti-inflammatory effects. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2014;34:1747–1755. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams JC, Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talme T, Bergdahl E, Sundqvist K-G. Regulation of t-lymphocyte motility, adhesion and de-adhesion by a cell surface mechanism directed by low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 and endogenous thrombospondin-1. Immunology. 2014;142:176–192. doi: 10.1111/imm.12229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheef EA, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N. Attenuation of proliferation and migration of retinal pericytes in the absence of thrombospondin-1. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00409.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniel C, Schaub K, Amann K, Lawler J, Hugo C. Thrombospondin-1 is an endogenous activator of tgf-β in experimental diabetic nephropathy in vivo. Diabetes. 2007;56:2982–2989. doi: 10.2337/db07-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultz-Cherry S, Murphy-Ullrich J. Thrombospondin causes activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta secreted by endothelial cells by a novel mechanism. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;122:923–932. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Dee Z, Pidcock K, Gutierrez LS. Thrombospondin-1: Multiple paths to inflammation. Mediators of Inflammation. 2011;2011:10. doi: 10.1155/2011/296069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rico MC, Manns JM, Driban JB, Uknis AB, Kunapuli SP, Dela Cadena RA. Thrombospondin-1 and transforming growth factor beta are pro-inflammatory molecules in rheumatoid arthritis. Translational Research. 2008;152:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moura R, Tjwa M, Vandervoort P, Van kerckhoven S, Holvoet P, Hoylaerts MF. Thrombospondin-1 deficiency accelerates atherosclerotic plaque maturation in apoe−/− mice. Circulation Research. 2008;103:1181–1189. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.185645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Tong X, Rumala C, Clemons K, Wang S. Thrombospondin1 deficiency reduces obesity-associated inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity in a diet-induced obese mouse model. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Csányi G, Yao M, Rodríguez AI, Ghouleh IA, Sharifi-Sanjani M, Frazziano G, Huang X, Kelley EE, Isenberg JS, Pagano PJ. Thrombospondin-1 regulates blood flow via cd47 receptor–mediated activation of nadph oxidase 1. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2012;32:2966–2973. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng TF, Turpie B, Masli S. Thrombospondin-1–mediated regulation of microglia activation after retinal injury. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2009;50:5472–5478. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masli S, Vega J. Ocular immune privilege sites. In: Cuturi MC, Anegon I, editors. Suppression and regulation of immune responses. Humana Press; 2011. pp. 449–458. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Favier J, Germain S, Emmerich J, Corvol P, Gasc J-M. Critical overexpression of thrombospondin 1 in chronic leg ischaemia. The Journal of Pathology. 2005;207:358–366. doi: 10.1002/path.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smadja DM, d'Audigier C, Bièche I, Evrard S, Mauge L, Dias J-V, Labreuche J, Laurendeau I, Marsac B, Dizier B, Wagner-Ballon O, Boisson-Vidal C, Morandi V, Duong-Van-Huyen J-P, Bruneval P, Dignat-George F, Emmerich J, Gaussem P. Thrombospondin-1 is a plasmatic marker of peripheral arterial disease that modulates endothelial progenitor cell angiogenic properties. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2011;31:551–559. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.220624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moxon JV, Padula MP, Clancy P, Emeto TI, Herbert BR, Norman PE, Golledge J. Proteomic analysis of intra-arterial thrombus secretions reveals a negative association of clusterin and thrombospondin-1 with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Browne PV, Mosher DF, Steinberg MH, Hebbel RP. Disturbance of plasma and platelet thrombospondin levels in sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology. 1996;51:296–301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199604)51:4<296::AID-AJH8>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daugherty A, Rateri DL, Charo IF, Owens AP, Howatt DA, Cassis LA. Angiotensin ii infusion promotes ascending aortic aneurysms: Attenuation by ccr2 deficiency in apoe−/− mice. Clinical Science. 2010;118:681–689. doi: 10.1042/CS20090372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maiellaro K, Taylor WR. The role of the adventitia in vascular inflammation. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;75:640–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tieu BC, Lee C, Sun H, LeJeune W, Recinos A, Ju X, Spratt H, Guo D-C, Milewicz D, Tilton RG, Brasier AR. An adventitial il-6/mcp1 amplification loop accelerates macrophage-mediated vascular inflammation leading to aortic dissection in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119:3637–3651. doi: 10.1172/JCI38308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Waard V, Bot I, de Jager SCA, Talib S, Egashira K, de Vries MR, Quax PHA, Biessen EAL, van Berkel TJC. Systemic mcp1/ccr2 blockade and leukocyte specific mcp1/ccr2 inhibition affect aortic aneurysm formation differently. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamanouchi D, Morgan S, Stair C, Seedial S, Lengfeld J, Kent KC, Liu B. Accelerated aneurysmal dilation associated with apoptosis and inflammation in a newly developed calcium phosphate rodent abdominal aortic aneurysm model. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2012;56:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sid B, Sartelet H, Bellon G, El Btaouri H, Rath G, Delorme N, Haye B, Martiny L. Thrombospondin 1: A multifunctional protein implicated in the regulation of tumor growth. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2004;49:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armstrong LC, Bornstein P. Thrombospondins 1 and 2 function as inhibitors of angiogenesis. Matrix Biology. 2003;22:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamauchi M, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Shibuya M. Novel antiangiogenic pathway of thrombospondin-1 mediated by suppression of the cell cycle. Cancer Science. 2007;98:1491–1497. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheef EA. Isolation and characterization of corneal endothelial cells from wild type and thrombospondin-1 deficient mice. Molecular Vision. 2007;13:1483–1495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Short SM, Derrien A, Narsimhan RP, Lawler J, Ingber DE, Zetter BR. Inhibition of endothelial cell migration by thrombospondin-1 type-1 repeats is mediated by β1 integrins. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2005;168:643–653. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo N-h, Krutzsch HC, Inman JK, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin 1 and type i repeat peptides of thrombospondin 1 specifically induce apoptosis of endothelial cells. Cancer Research. 1997;57:1735–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dawson DW, Pearce SFA, Zhong R, Silverstein RL, Frazier WA, Bouck NP. Cd36 mediates the in vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;138:707–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein JJ, Iwuchukwu C, Maier KG, Gahtan V. Thrombospondin-1–induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation are functionally dependent on microrna-21. Surgery. 2014;155:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morgan S, Yamanouchi D, Harberg C, Wang Q, Keller M, Si Y, Burlingham W, Seedial S, Lengfeld J, Liu B. Elevated protein kinase c-δ contributes to aneurysm pathogenesis through stimulation of apoptosis and inflammatory signaling. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2012;32:2493–2502. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.255661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamanouchi D, Morgan S, Kato K, Lengfeld J, Zhang F, Liu B. Effects of caspase inhibitor on angiotensin ii-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:702–707. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.200527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kong P, Cavalera M, Frangogiannis NG. The role of thrombospondin (tsp)-1 in obesity and diabetes. Adipocyte. 2014;3:81–84. doi: 10.4161/adip.26990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maier KG, Han X, Sadowitz B, Gentile KL, Middleton FA, Gahtan V. Thrombospondin-1: A proatherosclerotic protein augmented by hyperglycemia. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2010;51:1238–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raman P, Krukovets I, Marinic TE, Bornstein P, Stenina OI. Glycosylation mediates up-regulation of a potent antiangiogenic and proatherogenic protein, thrombospondin-1, by glucose in vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:5704–5714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K-I, Romeo MJ, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Kuppusamy P, Wink DA, Krishna MC, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 limits ischemic tissue survival by inhibiting nitric oxide–mediated vascular smooth muscle relaxation. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frangogiannis NG, Ren G, Dewald O, Zymek P, Haudek S, Koerting A, Winkelmann K, Michael LH, Lawler J, Entman ML. Critical role of endogenous thrombospondin-1 in preventing expansion of healing myocardial infarcts. Circulation. 2005;111:2935–2942. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Streit M, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Spencer L, Brown LF, Janes L, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Yano K, Hawighorst T, Iruela-Arispe L, Detmar M. Thrombospondin-1 suppresses wound healing and granulation tissue formation in the skin of transgenic mice. 2000 doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lawler J, Sunday M, Thibert V, Duquette M, George EL, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Thrombospondin-1 is required for normal murine pulmonary homeostasis and its absence causes pneumonia. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;101:982–992. doi: 10.1172/JCI1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van den Borne P, Quax PHA, Hoefer IE, Pasterkamp G. The multifaceted functions of cxcl10 in cardiovascular disease. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:11. doi: 10.1155/2014/893106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Subramanian V, Golledge J, Ijaz T, Bruemmer D, Daugherty A. Pioglitazone-induced reductions in atherosclerosis occur via smooth muscle cell–specific interaction with pparγ. Circulation Research. 2010;107:953–958. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.219089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawrence T, Natoli G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: Enabling diversity with identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:750–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Thomas GD, Hewitson JP, Duncan S, Brombacher F, Maizels RM, Hume DA, Allen JE. Il-4 directly signals tissue-resident macrophages to proliferate beyond homeostatic levels controlled by csf-1. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2013;210:2477–2491. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao AG, Frazier WA. Identification of a receptor candidate for the carboxyl-terminal cell binding domain of thrombospondins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:29650–29657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sick E, Jeanne A, Schneider C, Dedieu S, Takeda K, Martiny L. Cd47 update: A multifaceted actor in the tumour microenvironment of potential therapeutic interest. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2012;167:1415–1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamauchi Y, Kuroki M, Imakiire T, Uno K, Abe H, Beppu R, Yamashita Y, Kuroki M, Shirakusa T. Opposite effects of thrombospondin-1 via cd36 and cd47 on homotypic aggregation of monocytic cells. Matrix Biology. 2002;21:441–448. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(02)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frolova EG, Pluskota E, Krukovets I, Burke T, Drumm C, Smith JD, Blech L, Febbraio M, Bornstein P, Plow EF, Stenina OI. Thrombospondin-4 regulates vascular inflammation and atherogenesis. Circulation Research. 2010;107:1313–1325. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.232371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mansfield PJ, Suchard SJ. Thrombospondin promotes chemotaxis and haptotaxis of human peripheral blood monocytes. The Journal of Immunology. 1994;153:4219–4229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ishibashi M, Egashira K, Zhao Q, Hiasa K-i, Ohtani K, Ihara Y, Charo IF, Kura S, Tsuzuki T, Takeshita A, Sunagawa K. Bone marrow-derived monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor ccr2 is critical in angiotensin ii-induced acceleration of atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:e174–e178. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143384.69170.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schubl S, Tsai S, Ryer EJ, Wang C, Hu J, Kent KC, Liu B. Upregulation of protein kinase cdelta in vascular smooth muscle cells promotes inflammation in abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Surg Res. 2009;153:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sweetwyne MT, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin1 in tissue repair and fibrosis: Tgf-β-dependent and independent mechanisms. Matrix Biology. 2012;31:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krishna SM, Seto SW, Jose RJ, Biros E, Moran CS, Wang Y, Clancy P, Golledge J. A peptide antagonist of thrombospondin-1 promotes abdominal aortic aneurysm progression in the angiotensin ii–infused apolipoprotein-e–deficient mouse. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2015;35:389–398. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.