Abstract

Objectives

To examine factors associated with home delivery among women in Pwani Region, Tanzania, which has experienced a rapid rise in facility delivery coverage.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from a population-based survey of women residing in rural areas of Pwani Region were linked to health facility locations. We fitted multi-level logistic models to examine individual and community factors associated with home delivery.

Results

752 (27.95%) of the 2691 women who completed the survey delivered their last child at home. Women were less likely to deliver at home if they had any primary education (odds ratio [OR] 0.62; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.50, 0.79), were primiparous (OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.73), had more exposure to media (OR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.66, 0.96), or had received more (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.63, 0.96) or better quality antenatal care (ANC) services (OR: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.34, 0.67). Increased wealth was strongly associated with lower odds of home delivery (OR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.18, 0.39), as was living in a village that grew cash crops (OR: 0.56; 95% CI: 0.35, 0.88). Farther distance to hospital, but not to lower level facilities, was associated with higher likelihood of home delivery (OR 2.49; 95% CI: 1.60, 3.88).

Conclusions

Poverty, multiparity, weak ANC, and distance to hospital were associated with persistence of home delivery in a region with high coverage of facility delivery. A pro-poor path to universal coverage of safe delivery requires a greater focus on quality of care and more intensive outreach to poor and multiparous women.

Keywords: maternal health, facility utilization, multi-level models

Introduction

After decades of stagnation, several African countries and subnational regions are seeing a rise in facility delivery rates (Bhutta et al., 2010, Walker et al., 2013). These include Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Rwanda, where 71.6%, 62.8%, and 77.1% of women now deliver in health facilities, respectively (The DHS Program, 2014). This is a positive development as delivery conducted by skilled personnel with access to appropriate equipment and medicines is the most effective means to avert maternal and newborn mortality (Koblinsky et al., 2006, Lee et al., 2011). However, only 16 countries—and none in sub-Saharan Africa—will achieve the Millennium Development Goal 5 target of 75% reduction in maternal mortality by 2015 as compared to 1990 (Kassebaum et al., 2014). Reaching this goal will require universal coverage of high quality skilled delivery care.

One subnational region that has seen a dramatic rise in facility delivery coverage is Pwani Region, a populous rural region near the commercial capital of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam. In Pwani, the facility delivery rate increased from 43% in 2004 to 73% in 2010 (National Bureau of Statistics of Tanzania and ORC Macro, 2004, National Bureau of Statistics Tanzania and ICF Macro, 2011). While this is the largest rise among Tanzania’s 26 regions, 6 regions saw an increase in facility delivery rates of ten percentage points or more in the same timeframe.(National Bureau of Statistics of Tanzania and ORC Macro, 2004, National Bureau of Statistics Tanzania and ICF Macro, 2011) The reasons for the rise in Pwani are varied and include major education efforts on maternal mortality, the introduction of village health workers knowledgeable about the benefits of facility delivery, and facility improvement efforts from HIV and maternal child health programming.

As facility deliveries increase in low-income regions, it will likely become more challenging to bring women who continue to deliver at home into care. They may be more distant from care, less educated, or too poor to pay for medical or transportation costs. While there is substantial discussion about these “last mile” women, there has been little research on determinants of home and facility delivery in such settings. Most studies exploring utilization of facility delivery have been conducted in areas with low facility delivery coverage (Anyait et al., 2012, Chomat et al., 2011, Gebrehiwot et al., 2014, Kitui et al., 2013, Montagu et al., 2011). They find that a range of factors affects the place of delivery, from low education and poverty on the demand side to health service availability and fees on the supply side. There is also growing evidence that demand-side interventions, such as conditional-cash transfers and transport vouchers can increase facility delivery rates—again in areas with low baseline utilization (Glassman et al., 2013, Lagarde et al., 2009, Paul, 2010).

This study aims to fill a gap in the literature by examining how individual and health system factors are associated with place of delivery in a setting where the majority of deliveries occur in facilities. Using a multilevel model, we assess associations between demographic characteristics, community factors, and geographic availability of health facilities and the likelihood of home delivery. This information is relevant to policymakers working to achieve universal coverage of obstetric care in countries with high maternal and newborn mortality.

Methods

Data Sources

The current analysis uses baseline data, collected from December 2011 through April 2012, of an ongoing cluster-randomized study assessing maternal health care quality improvement models in primary care facilities in Pwani Region, Tanzania (ISRCTN1707760). Complete study setting and methods are described else where (Kruk et al., 2014a). Briefly, Pwani region is in Eastern Tanzania and is primarily rural. Each village is assigned to a primary health care facility, which may or may not be in the village, known as a dispensary that is equipped to perform deliveries. In addition, women can deliver in health centers—facilities with several inpatient beds—and each district has at least one district hospital capable of performing Caesarean sections.

The study population is women with deliveries in the past year who live in catchment areas of 24 study health facilities: government primary care clinics with at least one medically trained staff member (typically a clinical officer or nurse who were trained in basic obstetric care) and were actively providing delivery services.(Adegoke et al., 2012) Thus women in the study all lived in proximity to health facilities. Individual and village level data were collected from recently delivered women and village administrator interviews, respectively. Geocodes were obtained from all health facilities in the study area.

Individual participant data were collected through a census survey conducted between February and April 2012 of women living in the study area who delivered a child between six weeks and one year before interview, and were 15 years of age or older. All eligible women who provided written consent, or assent and consent from their guardian if a minor, were interviewed using a structured survey in Swahili on demographics, socio-economic status, maternal and newborn health knowledge, and care utilization. All participants lived within the catchment area of a primary health clinic that performs deliveries.

Village level data were collected through a semi-structured interview with a senior village administrator, usually the Village Executive Officer (VEO) or Chairman, between December 2011 and March 2012. Where VEOs were not available in the first round (12.9% of villages) the data were collected during return visits between February and April 2013. The interview collected data on village demographics and infrastructure. Villages in Tanzania are subdivided into sub-villages (kitongoji) or neighborhoods of approximately 1000 people for administrative purposes.

Data were collected using electronic tablets with regular uploads to a secure web-based server. Study personnel collected locations of all primary, secondary, and tertiary health facilities in the study districts as well as centers of sub-villages in the study area using Garmin Etrex 10 GPS receivers. The institutional review boards of Columbia University, the Ifakara Health Institute in Tanzania, and the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research provided ethical approval for the study.

Variables

The dependent variable for this analysis is the place of delivery for a woman’s most recent birth. Respondents who indicated a home birth (their own home or that of someone else) were compared with those who had a health facility birth. Women who delivered on their way to a health facility or did not respond were excluded from the analysis.

Drawing on Andersen’s model of health care utilization and the current literature on health facility utilization for delivery we identified four categories of factors that could influence women’s place of delivery: demographic and household characteristics, prior experiences with the health system, community characteristics, and women’s geographic access to the health system (Andersen, 1995). We further categorized these factors as individual-level and community-level characteristics.

Individual woman-level characteristics included in the final analysis were age, education (no formal education, any primary school attended, and any secondary school attended), primary occupation (farmer or homemaker versus all other occupations), self-rated health (one or more problems reported in the EQ-5D versus no problems reported), number of previous deliveries, and the most recent child’s birth season (non-harvest season versus harvest season). Age squared was included in addition to age to account for a possible U-shaped or other non-linear relationship between age and utilization. Principal components analysis was used to create a relative wealth index from 18 items about household asset ownership, categorizing women’s score into quintiles for analytic purposes (Filmer and Pritchett, 2001). Household assets were similar to those used in Demographic and Health Surveys and included electricity, ownership of a mobile phone, and meals per day, among others (National Bureau of Statistics Tanzania and ICF Macro, 2011).

Individual women’s health system utilization was assessed through reported number of ANC visits during her most recent pregnancy (women meeting the basic WHO recommendation of four visits per pregnancy are compared to those who fail to meet this threshold (Lincetto et al., 2006)). The number of ANC services received during ANC visits (an index of nine diagnostic, treatment, and counseling services) is also included as an indicator of ANC quality received. Because the association between frequency of ANC and facility delivery is well known, in this analysis we focused on the quality of ANC. To this end we restricted the analysis to women who had at least 1 ANC visit (96% of all women).

To assess a woman’s exposure to media, an additive media index was created using the frequency with which the woman reported listening to the radio, reading a newspaper, or watching TV (a maximum score of nine indicated that the woman used all three forms of media on a daily basis).

Other research has pointed to the importance of community characteristics, such as village size, wealth, and educational resources, in influencing facility utilization separately from individual and household factors (Kruk et al., 2010, Stephenson et al., 2006). After exploring a range of village characteristics, the following village-level characteristics were included in the final analysis: village population, presence of a secondary school in the village, the farming of cash crops and the number of water pumps, and shops in the village. The latter three were used as proxies for village wealth or level of economic development.

We included distance to different levels of health facilities (dispensaries, health centers, and hospitals) nearest to the study participants as measures of access to and choice of health facilities. We explicitly modeled the effects of distance to different levels of the health system given the growing evidence that many women bypass primary care for delivery (Kruk et al., 2014b). Distance variables were calculated using the SPHDIST command in Stata that measures the spherical distance from latitude and longitude coordinates collected in the center of each sub-village (kitongoji) to those for the respective end point. When coordinates for the sub-village were unavailable (16% of respondents), distance from the village center were used instead.

Statistical analyses

First, data were examined for distribution, missingness, and outliers through univariable analysis. The dependent variable was whether the woman’s most recent birth was at home (her own or another’s). Continuous variables were log transformed to improve linearity, where necessary.

Bivariable analyses were performed between the dependent variable and a wide range of individual and community variables identified by Anderson’s utilization model and recent literature, as noted above. Variables were selected for inclusion in the final model if they were a) statistically significant at a p<0.10 level or b) were theoretically important in our conceptual framework. Correlations among predictor variables were then calculated and variables that were highly correlated with others were removed from analysis. Using the final variable set, we estimated two separate 2-level logistic random intercept models: an individual level model, and a full model with individual and community level elements, using the XTMELOGIT procedure (Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, 2012). We calculated the proportion of variability in the odds of home delivery explained by model variables at each level. Stata version 13 (College Station, TX) was used for all analyses.

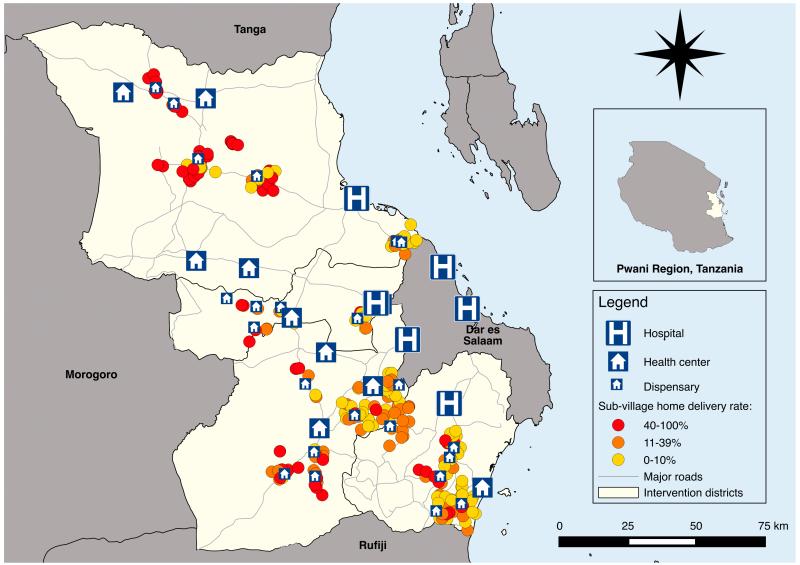

Finally, to visually represent associations between distance to facility and home delivery, we constructed a map of sub-village home delivery coverage and location of dispensaries, health centers, and hospitals. Home delivery rates were categorized into tertiles based on the distribution in the study population (0-10%, 11-39%, 40-100%) and to illustrate the worst, modal, and best performing sub-village distributions. To construct the maps we used QGIS version 2.20-Valmiera, 2014, a free open-source geographic information system.

Results

Of 3238 eligible women, 3019 participated in the survey (93%). Non-response was pre-dominantly due to non-availability of the respondent after three attempts to locate her (204/3238 [6%]) and in a few cases because of refusal (15 [< 1%]). 116 women reported having zero ANC visits, and were excluded from the analytic sample (3.8%). 2,691 women in 76 villages had complete data and were included in this analysis. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for study variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of study sample, Pwani Region, Tanzania, 2012.

| frequency (%) | mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Women (n=2,691) | ||

| Dependent variable: delivered at home | 752 (27.95) | |

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 27.12 (6.88) | |

| Religion | ||

| Christian | 499 (18.55) | |

| Muslim | 2,191 (81.45) | |

| Currently married* | 2,230 (82.87) | |

| Education | ||

| No formal education | 698 (25.94) | |

| Any primary | 1,738 (64.59) | |

| Any secondary | 255 (9.48) | |

| Primary occupation, farmer or homemaker† | 2,170 (81.89) | |

| Self-rated health, good‡ | 1,868 (69.44) | |

| Number of previous deliveries | 2.28 (2.12) | |

| Primipara | 646 (24.01) | |

| Birth during harvest season | 458 (17.02) | |

| Media use index (0-9)§ | 3.32 (1.86) | |

| Household assets | ||

| Electricity | 176 (6.54) | |

| Mobile phone | 1,994 (74.10) | |

| Health care utilization | ||

| 4+ antenatal care visits for this pregnancyζ | 1,769 (65.74) | |

| Number of antenatal care services received (1-9)∥ | 6.97 (1.61) | |

| Level 2: Communities (n=76) | ||

| Village population | 1,965 (1,627) | |

| Village farms cash cropsξ | 41 (53.95) | |

| Secondary school in village | 16 (21.05) | |

| Number of water pumps in village | 4.76 (5.02) | |

| Number of shops in village | 9.64 (14.14) | |

| Distance to primary care facility (km)ϑ | 3.86 (3.05) | |

| Distance to health center (km) ϑ | 17.41 (7.71 | |

| Distance to hospital (km) ϑ | 39.00 (18.54) |

Notes:

Includes legal marriages and cohabitating couples.

Includes homemakers, farmers, and house cleaning.

Based on no ‘problem’ ratings on a scale of five items from EQ-5D (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression).

Mass media index constructed from self-reported frequency of access to newspaper, TV, and radio (range 0 – 9).

116 women had zero ANC visits (3.8%) and were not included in the sample.

Antenatal services received include recommended diagnostic, treatment, and counseling services (min value=1, max value=9).

Cash crops include cashew, pineapple, tobacco, coconut, orange, and tangerine. Cash crops were identified based on the Tanzania National Sample Census of Agriculture (National Bureau of Statistics, 2007) and interviews with village executives.

All distances are straight line distances from sub-village center (n=252). Where sub-village was unknown, village was used.

Table 2 presents the results of the multi-level logistic regression models. In the final model (Model 2), women who were primiparous (OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.37, 0.73), had at least four ANC visits during their pregnancy (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.63, 0.96), and who received more ANC services at those visits (OR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.34, 0.67) were significantly less likely to have delivered their most recent child at home. Compared to women with no formal education, women with any primary education were significantly less likely to have delivered at home (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.50, 0.79). At all levels of wealth, richer women were significantly less likely to have delivered at home than the poorest quintile of women (lower-middle quintile OR = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.46, 0.83; middle quintile OR = 0.43; 95% CI = 0.31, 0.59; higher-middle quintile OR = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.34, 0.66; and highest quintile OR = 0.27; 95% CI = 0.18, 0.39). Women were less likely to have delivered their most recent child at home if their media use index was higher; a 10% increase in the media index score was associated with a 2% reduction in the odds of home delivery (OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.66, 0.96).

Table 2. Results of multilevel logistic regression of home delivery in Pwani Region, Tanzania, 2012, N = 2,691.

| Model 1 OR* [95% CI] |

P | Model 2 OR [95% CI] |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||||

| Individual variables | ||||

| Age | 1.02 [0.90, 1.15] |

0.74 | 1.02 [0.90, 1.15] |

0.7 7 |

| Age2 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

0.68 | 1.00 [1.00, 1.00] |

0.7 1 |

| Education | ||||

| No formal | Reference | Reference | ||

| Any primary | 0.62 [0.50, 0.79] |

<0.0 1 |

0.62 [0.50, 0.79] |

<0.0 1 |

| Any secondary | 0.63 [0.40, 0.99] |

0.05 | 0.64 [0.41, 1.02] |

0.0 6 |

| Birth during harvest sea- son |

0.76 [0.58, 1.00] |

0.05 | 0.77 [0.59, 1.02] |

0.0 7 |

| Primipara | 0.52 [0.37, 0.73] |

<0.0 1 |

0.52 [0.37, 0.73] |

<0.0 1 |

| Media use index (ln)† | 0.79 [0.66, 0.95] |

0.01 | 0.80 [0.66, 0.96] |

0.0 2 |

| Wealth quintile | ||||

| Lowest | Reference | Reference | ||

| Lower middle | 0.61 [0.45, 0.83] |

<0.0 1 |

0.62 [0.46, 0.83] |

<0.0 1 |

| Middle | 0.42 [0.31, 0.58] |

<0.0 1 |

0.43 [0.31, 0.59] |

<0.0 1 |

| Higher middle | 0.46 [0.33, 0.64] |

<0.0 1 |

0.47 [0.34, 0.66] |

<0.0 1 |

| Highest | 0.26 [0.17, 0.38] |

<0.0 1 |

0.27 [0.18, 0.39] |

<0.0 1 |

| Health care utilization | ||||

| 4+ ANC visits ζ | 0.78 [0.63, 0.96] |

0.02 | 0.78 [0.63, 0.96] |

0.0 2 |

| No. of ANC services re- ceived (ln)‡ |

0.46 [0.33, 0.65] |

<0.0 1 |

0.48 [0.34, 0.67] |

<0.0 1 |

| Village-level variables | ||||

| Village population (ln) | 1.03 [0.73, 1.45] |

0.8 6 |

||

| Village farms cash cropsξ | 0.56 [0.35, 0.88] |

0.0 1 |

||

| Secondary school in vil- lage |

0.67 [0.38, 1.17] |

0.1 6 |

||

| Number of water pumps in village |

0.98 [0.93, 1.03] |

0.3 8 |

||

| Number of shops in village | 1.01 [0.99, 1.03] |

0.3 9 |

||

| Distance from village to§ primary clinic (ln km) |

1.07 [0.97, 1.19] |

0.1 5 |

||

| health center (ln km) | 1.04 [0.71, 1.53] |

0.8 4 |

||

| hospital (ln km) | 2.49 [1.60, 3.88] |

<0.0 1 |

||

| Random Effects | ||||

| Variance between villages | 1.20 [0.76, 1.88] |

0.58 [0.32, 1.03] |

||

| Intraclass correlation (ρ) | 0.27 [0.19, 0.36] |

0.15 [0.09, 0.24] |

Notes: Model 1, individual variables; Model 2, individual+village variables.

adjusted odds ratio for fixed effects and variance for random intercept; CI indicates confidence interval.

Mass media index constructed from self-reported frequency of access to news, TV, and radio (range 0 – 9).

116 women had zero ANC visits (3.8%) and were not included in the sample.

ANC services received include standard diagnostic, treatment, and counseling services (range 1-9).

Distances calculated from sub-village center. Where sub-village center data was unavailable, village was used.

Cash crops include cashew, pineapple, tobacco, coconut, orange, and tangerine. Cash crops were identified based on the Tanzania National Sample Census of Agriculture (National Bureau of Statistics, 2007) and interviews with village executives.

At the community level, women who lived in villages that farmed cash crops were less likely to have delivered at home (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.35, 0.88). Women’s distance from the nearest hospital was strongly associated with an increased likelihood of home delivery (OR = 2.49, 95% CI = 1.60, 3.88). Distance from the nearest health center and dispensary were not associated with likelihood of home delivery. This is also seen in Figure 1, where sub-villages with highest home delivery rates tended to be farthest from hospitals, although most were proximal to primary care facilities.

Figure 1.

Location of study dispensaries, hospitals, and study sub-villages coded by home delivery rates.

Notes: Sub-village were classified as having low, medium, or high home delivery rates based on tertiles of the proportion of respondents in each sub-village with home deliveries: 0-10% (low), 11-39% (medium), and 40-100% (high).

The random effects results in Table 2 indicate that the addition of village-level factors to the analysis (moving from model 1 to model 2) reduces the unexplained variance between villages from 1.20 (95% CI = 0.76, 1.88) to 0.58 (95% CI = 0.32, 1.03), and reduces the intraclass correlation of women within villages (ρ) from 0.27 (95% CI = 0.19, 0.36) to 0.15 (95% CI = 0.09, 0.24). A likelihood ratio test comparing model 2 to a regular logistic regression model with the same independent variables confirms the validity of using the multi-level model (χ2= 85.23, P<0.01).

Discussion

This analysis of home delivery among women living in a rural area with high coverage of facility delivery highlights the importance of socioeconomic vulnerability, parity, prior health care, and availability of comprehensive obstetric care as remaining barriers to universal facility delivery. Although the majority of their peers delivered in a facility, poor and uneducated women were substantially more likely to deliver at home. The odds of delivery at home for a woman in the poorest 20% of this population were almost four times those of her neighbor in the wealthiest 20%. This is the case despite a long-standing policy of free delivery in Tanzania and confirms findings from other research that clinical fees are not the only costs that women have to bear (Mrisho et al., 2007). Other research has shown that costs of transport, medical supplies such as gloves, plastic sheets, and IV tubing, and food and accommodation can impose a major burden on poor families and dissuade women from seeking care (Khan, 2005, Kruk et al., 2008).

Whereas secondary education has been shown to be the critical threshold for motivating facility delivery in regions with lower delivery coverage (Tsawe and Susuman, 2014, van Eijk et al., 2006), here we found that women with primary and secondary education were equally more likely to deliver in facilities compared to women with no education, without evidence of a step-wise association. The association between women’s low educational attainment and facility delivery is well documented in the literature. (Ahmed et al., 2010, Danforth et al., 2009, Levira et al., 2014)

In Tanzania, as in other countries, women giving birth for the first time are considered to be high risk and providers typically would strongly recommend facility delivery (Magadi et al., 2001). Clearly this message is getting through: the odds of home delivery for first-time mothers, irrespective of age, were half the odds of home delivery for women who had previously delivered. The influence of primiparity on facility delivery has also been confirmed in other settings (Kruk et al., 2010, Navaneetham and Dharmalingam, 2002, Ndao-Brumblay et al., 2012, Onah et al., 2006). However, birth complications and maternal and new-born deaths can occur in any delivery and thus renewed efforts are required by providers to encourage women with higher order births to deliver in facilities.

The quantity and quality of antenatal care remain important drivers of place of delivery in this high coverage setting. Women with four or more ANC visits were less likely to deliver at home as were women who obtained more of the recommended ANC services. Frequency of ANC has been shown to influence place of delivery in other work (Adjiwanou and Legrand, 2013, Exavery et al., 2014, Guliani et al., 2012, Moyer and Mustafa, 2013, Rockers et al., 2009). Obtaining all recommended antenatal services is a marker for quality of care and other work has documented that poor care quality in the health system can steer women to delivering at home (Mselle et al., 2013). Fewer studies have examined the role of media exposure on facility delivery (Babalola and Fatusi, 2009). We found that women who listen to radio, watch TV, or read the newspaper more frequently are less likely to give birth at home. This information from outside the village exposes women to modern and urban mores and is a potential source of information about safe motherhood.

We explored whether village wealth was associated with home delivery after adjusting for women’s individual wealth. The farming of cash crops was linked to a substantially lower probability of home delivery. The sale of cash crops brings income that can be used for improving clinics and roads and generally expands the resources available in the community, including presumably for health care costs. The other village level variables, such as secondary school, water pumps, and shops, while significant in bivariable analysis, were not associated with home delivery in adjusted analyses. These findings suggest that community wealth may to some extent counteract individual circumstances to support health care access, consistent with recent findings from Rufiji District, Tanzania.(Levira et al., 2014)

In terms of geographic accessibility to health care facilities, we found that distance to the nearest primary care clinic (dispensary), was not associated with place of delivery. This may be because most women lived close to these facilities, typically less than an hour’s walk away or within 5 km (National Institute for Medical Research, 2008). However, distance to the nearest hospital had a large and positive association with home delivery: a 10% increase in distance led to 9% higher odds of home delivery. Distance to hospital has been shown to be a driver of delivery decisions in other work (Gage and Guirlene Calixte, 2006, Mills et al., 2008, Tlebere et al., 2007). However, these studies were done in areas with lower coverage of facility delivery and did not include distance to all the levels of the health system as variables in the model.

Why do women continue to deliver at home, despite proximity to primary care facilities that conduct deliveries, in the context of high facility delivery coverage? Some of the reasons may include persisting cultural practices such as faith in traditional birth attendants or desire to bury the placenta near the home. However, it is also possible that as the proportion of facility births rises, women’s expectations of the health system rise accordingly and they may prefer to deliver at a hospital rather than their local clinic—and if this is not feasible deliver at home. It is possible that some women attempt to seek care at the primary care facility but providers may be absent or unavailable prompting women to travel to hospital. It is also relatively common for women to experience dismissive or disrespectful treatment by health workers, which dissuades women from facility delivery (Kruk et al., 2014c). This may be a rational reaction to the generally poor infrastructure and quality of care in low-volume clinics (Hsia et al., 2011). Women may also be concerned about privacy and be averse to be attended by providers who live in their community. Villages distant from district hospitals and thus urban centers, might adhere to more traditional delivery practices. However, we controlled for a wide range of socioeconomic factors as well as media exposure so this is unlikely to explain the findings fully. An additional explanation might be that access roads to sub-villages, which are typically unpaved, might be of progressively poor quality and transport options may be fewer in more remote communities, inhibiting travel to any facility. Further qualitative work would illuminate the mechanisms behind the associations found here.

This study had several limitations. Cross-sectional data do not permit causal inference and longitudinal work will be required to assess how women make decisions as coverage of care rises over time. Future research should also use qualitative approaches to confirming the hypotheses here about how women trade proximity with quality of facilities. Due to data limitations, we employed straight-line (Euclidian) rather than road distances although the latter would have more realistically represented women’s travel time. However, recent work comparing Euclidian distance with network distance (distance along roads) found the two to be comparable in identifying nearest health facilities in a rural African setting (Nesbitt et al., 2014). The quality of ANC received in this study was measured by a nine-item self-report additive index, subject to non-differential recall bias. Future studies could improve the precision of these findings with direct observation and quality evaluation of ANC visits. The findings here do not apply to populations with different demographic characteristics and health system contexts than that of the study population.

This study is one of few to focus on areas with high coverage of facility delivery in a rural, high-mortality setting (Ng’anjo Phiri et al., 2014). In an area where fewer than one in three women still deliver at home, poverty and lack of education hinder the remaining women from obtaining professional assistance for delivery even when this service is nominally free. We further find that provision of robust antenatal care provides an important link to facility delivery, and conversely, that low antenatal care attendance is a signal of lower likelihood to return to facility for delivery—whether due to poor care from the health system or perception of low obstetric risk. This is a potential point for policy intervention.

Finally, in areas of high coverage, it is proximity to hospitals not primary care clinics that matters to women, possibly because of growing expectations for high quality of care that is difficult for low-volume clinics to achieve. This has important implications for health system organization and demand-side support, such as vouchers, for transport to hospitals. Concentrating deliveries in more advanced health facilities is likely to improve maternal and newborn survival (McKinnon et al., 2014, Ronsmans et al., 2009). Our village and health system variables substantially reduced, though did not eliminate, area-level effects on individuals’ place of delivery, suggesting that the model captured the most important contextual influences on obstetric care seeking behavior—in this case village wealth and distance from hospital care.

As facility delivery coverage expands in parts of the world struggling with high maternal and new-born mortality, it will be critical for policymakers to implement policies that address the exclusion of vulnerable women from safe childbirth. Specifically, this work cautions against assuming that provision of free deliveries in primary care facilities will result in universal coverage of facility delivery. Support to poor and multiparous women to deliver in facility, such as vouchers and conditional cash transfers, should be considered to ensure equitable utilization. Policies to improve access to high volume, high quality facilities will also assist in closing the coverage gaps while assuring that who deliver in facilities do so safely.

Acknowledgements

We thank Angela Kimweri for her capable supervision of the fieldwork for the study, and Drs. Redempta Mbatia and Kasanga Mkambu for leadership of the study intervention. We are also grateful to Dr. Neema Rusibamayila of the Ministry of Health, and the Bagamoyo, Kisarawe, Kibaha Rural, and Mkuranga District Health authorities and health workers for their continual support of the study. Last, we would like to thank the interviewers, and acknowledge the women and community leaders of Pwani Region for generously sharing their health system experiences. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, grant number 1R01 AI093182.

References

- Adegoke A, Utz B, Msuya SE, van den Broek N. Skilled Birth Attendants: who is who? A descriptive study of definitions and roles from nine Sub Saharan African countries. PloS one. 2012;7:e40220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjiwanou V, Legrand T. Does antenatal care matter in the use of skilled birth attendance in rural Africa: a multi-country analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;86:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PloS one. 2010;5:e11190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does it Matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anyait A, Mukanga D, Oundo GB, Nuwaha F. Predictors for health facility delivery in Busia district of Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babalola S, Fatusi A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria--looking beyond individual and household factors Determinants of the uptake of the full dose of diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus vaccines (DPT3) in Northern Nigeria: a multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, Berman P, Boerma T, Bryce J, Bustreo F, Cavagnero E, Cometto G, Daelmans B, de Francisco A, Fogstad H, Gupta N, Laski L, Lawn J, Maliqi B, Mason E, Pitt C, Requejo J, Starrs A, Victora CG, Wardlaw T. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000-10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet. 2010;375:2032–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomat AM, Grundy J, Oum S, Bermudez OI. Determinants of utilisation of intrapartum obstetric care services in Cambodia, and gaps in coverage. Glob Public Health. 2011;6:890–905. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.572081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danforth EJ, Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Mbaruku G, Galea S. Household decision-making about delivery in health facilities: evidence from Tanzania. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27:696–703. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i5.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exavery A, Kante A, Njozi M, Tani K, Doctor H, Hingora A, Phillips J. Access to institutional delivery care and reasons for home delivery in three districts of Tanzania. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2014;13:48. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data--or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–32. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage AJ, Guirlene Calixte M. Effects of the physical accessibility of maternal health services on their use in rural Haiti. Popul Stud (Camb) 2006;60:271–88. doi: 10.1080/00324720600895934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebrehiwot T, San Sebastian M, Edin K, Goicolea I. Health workers’ perceptions of facilitators of and barriers to institutional delivery in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman A, Duran D, Fleisher L, Singer D, Sturke R, Angeles G, Charles J, Emrey B, Gleason J, Mwebsa W, Saldana K, Yarrow K, Koblinsky M. Impact of conditional cash transfers on maternal and newborn health. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31:48–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guliani H, Sepehri A, Serieux J. What impact does contact with the prenatal care system have on women’s use of facility delivery? Evidence from low-income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1882–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia RY, Mbembati NA, Macfarlane S, Kruk ME. Access to emergency and surgical care in sub-Saharan Africa: the infrastructure gap. Health Policy and Planning. 2011 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, Gonzalez-Medina D, Barber R, Huynh C, Dicker D, Templin T, Wolock TM, Ozgoren AA, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abubakar I, Achoki T, Adelekan A, Ademi Z, Adou AK, Adsuar JC, Agardh EE, Akena D, Alasfoor D, Alemu ZA, Alfonso-Cristancho R, Alhabib S, Ali R, Al Kahbouri MJ, Alla F, Allen PJ, AlMazroa MA, Alsharif U, Alvarez E, Alvis-Guzman N, Amankwaa AA, Amare AT, Amini H, Ammar W, Antonio CA, Anwari P, Arnlov J, Arsenijevic VS, Artaman A, Asad MM, Asghar RJ, Assadi R, Atkins LS, Badawi A, Balakrishnan K, Basu A, Basu S, Beardsley J, Bedi N, Bekele T, Bell ML, Bernabe E, Beyene TJ, Bhutta Z, Bin Abdulhak A, Blore JD, Basara BB, Bose D, Breitborde N, Cardenas R, Castaneda-Orjuela CA, Castro RE, Catala-Lopez F, Cavlin A, Chang JC, Che X, Christophi CA, Chugh SS, Cirillo M, Colquhoun SM, Cooper LT, Cooper C, da Costa Leite I, Dandona L, Dandona R, Davis A, Dayama A, Degenhardt L, De Leo D, del Pozo-Cruz B, Deribe K, Dessalegn M, deVeber GA, Dharmaratne SD, Dilmen U, Ding EL, Dorrington RE, Driscoll TR, Ermakov SP, Esteghamati A, Faraon EJ, Farzadfar F, Felicio MM, Fereshtehnejad SM, de Lima GM, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:980–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S. Free does not mean affordable: maternity patient expenditures in a public hospital in Bangladesh. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2005;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitui J, Lewis S, Davey G. Factors influencing place of delivery for women in Kenya: an analysis of the Kenya demographic and health survey, 2008/2009. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, Mavalankar D, Mridha MK, Anwar I, Achadi E, Adjei S, Padmanabhan P, Marchal B, De Brouwere V, van Lerberghe W. Going to scale with professional skilled care. Lancet. 2006;368:1377–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M, Hermosilla S, Larson E, Mbaruku G. Bypassing primary clinics for childbirth in rural Tanzania: a census of 3,019 deliveries. World Health Organization Bulletin. 2014a doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M, Mbaruku G, Rockers P, Galea S. User fee exemptions are not enough: out-of-pocket payments for ‘free’ delivery services in rural Tanzania. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2008;13:1442–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk ME, Hermosilla S, Larson E, Mbaruku GM. Bypassing primary care clinics for childbirth: a cross-sectional study in the Pwani region, United Republic of Tanzania. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014b;92:246–53. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk ME, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Ramsey K, Moyo W, Freedman LP. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: a facility and community survey. Health Policy and Planning. 2014c doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Mbaruku G, Paczkowski MM, Galea S. Community and health system factors associated with facility delivery in rural Tanzania: a multilevel analysis. Health Policy. 2010;97:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. The impact of conditional cash transfers on health outcomes and use of health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD008137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AC, Cousens S, Darmstadt GL, Blencowe H, Pattinson R, Moran NF, Hofmeyr GJ, Haws RA, Bhutta SZ, Lawn JE. Care during labor and birth for the prevention of intrapartum-related neonatal deaths: a systematic review and Delphi estimation of mortality effect. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levira F, Gaydosh L, Ramaiya A. Female migrants, family members and community socio-demographic characteristics influence facility delivery in Rufiji, Tanzania. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014;14:329. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincetto O, Mothebesoane-Anoh S, Gomez P, Munjanja S. Antenatal care. In: Joy L, Kate K, editors. Opportunities for Africa’s newborns: Practical data, policy and programmatic support for newborn care in Africa. PMNCH; Cape Town: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Magadi M, Madise N, Diamond I. Factors associated with unfavourable birth outcomes in Kenya. J Biosoc Sci. 2001;33:199–225. doi: 10.1017/s0021932001001997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon B, Harper S, Kaufman JS, Abdullah M. Distance to emergency obstetric services and early neonatal mortality in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:780–90. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S, Williams JE, Adjuik M, Hodgson A. Use of health professionals for delivery following the availability of free obstetric care in northern Ghana. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:509–18. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0288-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagu D, Yamey G, Visconti A, Harding A, Yoong J. Where do poor women in developing countries give birth? A multi-country analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer CA, Mustafa A. Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2013;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrisho M, Schellenberg JA, Mushi AK, Obrist B, Mshinda H, Tanner M, Schellenberg D. Factors affecting home delivery in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:862–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mselle LT, Moland KM, Mvungi A, Evjen-Olsen B, Kohi TW. Why give birth in health facility? Users’ and providers’ accounts of poor quality of birth care in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:174. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics . National Sample Census of Agriculture. Regional Report: Pwani Region. Periodical National Sample Census of Agriculture. Regional Report: Pwani Region [Online], Volume Vf: Regional Report: Pwani Region. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of Tanzania & ORC Macro Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Periodical Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2004 [Online] 2004 Available: http://www.measuredhs.com.

- National Bureau of Statistics Tanzania and ICF Macro [Accessed 3/6/2013];Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. 2011 Available: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR243/FR243%5B24June2011%5D.pdf.

- National Institute for Medical Research Evidence-informed policy making in the United Republic of Tanzania: Setting REACH-policy initiative priorities for 2008-2010. Periodical Evidence-informed policy making in the United Republic of Tanzania: Setting REACH-policy initiative priorities for 2008-2010 [Online] 2008 Available: http://www.eac.int/health/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=6&Itemid=148.

- Navaneetham K, Dharmalingam A. Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:1849–1869. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndao-Brumblay SK, Mbaruku G, Kruk ME. Parity and institutional delivery in rural Tanzania: a multilevel analysis and policy implications. Health Policy and Planning. 2012 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt RC, Gabrysch S, Laub A, Soremekun S, Manu A, Kirkwood BR, Amenga-Etego S, Wiru K, Hofle B, Grundy C. Methods to measure potential spatial access to delivery care in low- and middle-gncome countries: a case study in rural Ghana. Int J Health Geogr. 2014;13:25. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-13-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng’anjo Phiri S, Kiserud T, Kvale G, Byskov J, Evjen-Olsen B, Michelo C, Echoka E, Fylkesnes K. Factors associated with health facility childbirth in districts of Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia: a population based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onah HE, Ikeako LC, Iloabachie GC. Factors associated with the use of maternity services in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:1870–1878. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul VK. India: conditional cash transfers for in-facility deliveries. Lancet. 2010;375:1943–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60901-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. Stata Press; College Station, Texas: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rockers PC, Wilson ML, Mbaruku G, Kruk ME. Source of antenatal care influences facility delivery in rural Tanzania: a population-based study. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:879–85. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronsmans C, Scott S, Qomariyah S, Achadi E, Braunholtz D, Marshall T, Pambudi E, Witten K, Graham WJ. Professional assistance during birth and maternal mortality in two Indonesian districts. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2009;87:416–423. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.051581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N. Contextual Influences on the Use of Health Facilities for Childbirth in Africa. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:84–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The DHS Program . DHS Statcompiler [Online] The DHS Program; 2014. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/data/STATcompiler.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- Tlebere P, Jackson D, Loveday M, Matizirofa L, Mbombo N, Doherty T, Wigton A, Treger L, Chopra M. Community-based situation analysis of maternal and neonatal care in South Africa to explore factors that impact utilization of maternal health services. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52:342–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsawe M, Susuman AS. Determinants of access to and use of maternal health care services in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a quantitative and qualitative investigation. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:723. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eijk AM, Bles H, Odhiambo F, et al. Use of antenatal services and delivery care among women in rural western Kenya; a community based survey. Reproductive Health. 2006;3:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker N, Yenokyan G, Friberg IK, Bryce J. Patterns in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health interventions: projections of neonatal and under-5 mortality to 2035. Lancet. 2013;382:1029–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]