Abstract

Background

Although drinking for tension reduction has long been posited as a risk factor for alcohol-related problems, studies investigating anxiety in relation to risk for alcohol problems have returned inconsistent results, leading researchers to search for potential moderators. Negative urgency (the tendency to become behaviorally dysregulated when experiencing negative affect) is a potential moderator of theoretical interest because it may increase risk for alcohol problems among those high in negative affect. The present study tested a cross-sectional mediated moderation hypothesis whereby an interactive effect of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol problems is mediated through coping-related drinking motives.

Method

The study utilized baseline data from a hazardously drinking sample of young adults (N = 193) evaluated for participation in a randomized controlled trial of naltrexone and motivational interviewing for drinking reduction.

Results

The direct effect of anxiety on physiological dependence symptoms was moderated by negative urgency such that the positive association between anxiety and physiological dependence symptoms became stronger as negative urgency increased. Indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol problems (operating through coping motives) were also observed.

Conclusions

Although results of the current cross-sectional study require replication using longitudinal data, the findings suggest that the simultaneous presence of anxiety and negative urgency may be an important indicator of risk for AUDs via both direct interactive effects and indirect additive effects operating through coping motives. These findings have potentially important implications for prevention/intervention efforts for individuals who become disinhibited in the context of negative emotional states.

Keywords: alcohol-related problems, anxiety, negative urgency, coping motives

INTRODUCTION

The notion that anxious individuals are predisposed to use alcohol and to develop alcohol problems is a popular one, having been investigated in many forms since Conger (1956) first articulated the tension-reduction hypothesis. Epidemiological research has clearly established that clinically significant anxiety (i.e., meeting criteria for an anxiety disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)) is a risk factor for alcohol dependence (e.g., Grant et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 1997). However, results from studies examining the relationship between anxiety symptoms and alcohol use and problems in individuals not diagnosed with anxiety disorders have been equivocal.

Although a number of studies have identified positive relations between different anxiety constructs and both alcohol use and problems (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2007, Stewart et al., 1995; also see DeMartini & Carey, 2011) others have failed to identify a significant link. For example, in a daily diary study of U.S. college students, Armeli et al. (2008) found no main effect of daily anxiety on level of alcohol consumption. Similarly, Novak et al. (2003) found that anxiety sensitivity was not predictive of quantity of alcohol consumption among college students. With respect to social anxiety, Ham et al. (2007) found that anxiety level was negatively related to weekly alcohol use and unrelated to alcohol problems. Finally, in a study of Australian young adults (ages 20–24) both very light drinkers (less than 1 standard drink per week) and very heavy drinkers (more than 18 standard drinks per week) reported more past-month anxiety symptoms than moderate drinkers (1 to 8.5 standard drinks per week) (Caldwell et al., 2002), suggesting a potential curvilinear relationship between anxiety symptoms and alcohol use. Although it is possible that inconsistent findings across studies are due to differences in anxiety constructs or measures (e.g. social anxiety vs. anxiety sensitivity), even within a particular anxiety construct results are varied and complex (DeMartini & Carey, 2011; Schry & White, 2013).

The presence of inconsistent results has led researchers to search for potential moderators of the relationship between anxiety and drinking outcomes in non-clinically anxious individuals. For example, recent studies have shown that impulsivity moderates associations between negative affect and both alcohol consumption and problems, such that these associations are stronger among those higher in impulsivity (e.g., Simons et al., 2005; King et al., 2011). Regarding anxiety specifically, negative urgency (a type of impulsivity that is related to neuroticism) has emerged as a potential moderator. Negative urgency refers to the tendency or predisposition for an individual to become impulsive and act in an uncontrolled manner when experiencing negative affect (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Given that negative urgency involves the expression of risky behavior in the presence of negative affect, individuals high in negative urgency who also frequently experience negative affect might be at particularly high risk for alcohol-related problems.

Two studies to date have examined data related to this hypothesis. In a study of college students using ecological momentary assessment, Simons et al. (2010) found that daytime anxiety was positively associated with evening level of alcohol intoxication (estimated BAC) among those high in negative urgency (1 standard deviation above the sample mean) but not among those low in negative urgency (1 standard deviation below the sample mean). However, the authors did not find a significant relationship between daytime anxiety and evening alcohol problems (e.g., vomiting, drinking more than planned), nor did they examine negative urgency as a moderator of this relationship. Further, because this study used only a momentary (i.e., acute) measure of anxiety, it is unclear if similar findings would emerge with a measure of typical anxiety symptoms.

Despite a strong conceptual foundation for negative urgency as a moderator of the influence of anxiety on alcohol problems, the 1 study directly examining this hypothesis failed to find a significant interaction (Karyadi & King, 2011). Although it is possible that negative urgency does not moderate the influence of anxiety on alcohol problems, aspects of the study sample may also have contributed to the null results. Karyadi and King (2011) utilized a normative college sample reporting relatively few alcohol-related problems. Thus, restricted variability in the outcome of interest could have limited the ability to detect significant interactions. Investigating this question in a sample with a higher prevalence of (and therefore potentially greater variability in) alcohol problems would substantially contribute to our understanding of the potential moderating role of negative urgency.

Identifying populations at greatest risk for negative drinking outcomes associated with elevated anxiety and negative urgency would also be beneficial from a prevention/intervention perspective. Even more beneficial from this perspective would be knowledge of the mechanisms through which these risk factors operate. Prior literature suggests that drinking motives are a common final pathway through which more distal factors (like personality and other trait variables) operate (Cooper et al., 1995). For example, coping motives have been shown to mediate the effects of both anxiety (Ham et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2001) and negative urgency (Adams et al., 2012; Coskunpinar & Cyders, 2012; Settles et al., 2010) on alcohol use and problems.

Based on the literature reviewed above, the current study proposed a cross-sectional mediated moderation model in which we hypothesized that the indirect effect of anxiety on alcohol problems through coping motives would be stronger among those with higher levels of negative urgency (see Figure 1 for a diagram of the hypothesized model). Although social and enhancement motives are well-established predictors of alcohol-related problems, we did not include them in our hypothesized model because they are less clearly linked to negative affect (also see Footnote 2 in Results section). Gender and baseline drinking (total number of drinks in the past three months) were included as covariates in all models. Gender was included given well established gender differences in both anxiety (women higher than men (Stewart et al., 1997)) and alcohol-related problems (men higher than women (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004)). Alcohol use was included as a covariate as we were interested in understanding the unique effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol-related problems after controlling for levels of consumption.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Mediated Moderation Model

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were drawn from a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of naltrexone in combination with motivational interviewing for drinking reduction (O’Malley et al., 2015). Data were from pre-randomization baseline, so all participants who met initial eligibility criteria to complete the in-person intake session were included in the analyses, regardless of whether they ultimately met criteria for enrollment in the trial. Eligibility to complete the in-person screening was based on a phone screening. Participants were excluded at the level of the phone screening if they reported inability to read and write in English, being pregnant or nursing, medical contraindications to study medication (Naltrexone), less than two binge drinking episodes in the past month, any past-month opioid use, more than weekly use of other drugs (or daily use of marijuana), or self-reported serious psychiatric conditions (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia). A total of 193 participants met initial eligibility criteria for the in-person screening and completed at least a portion of a web-based intake survey (mean completion percentage was 98%, with 185 participants completing 100% of the survey) that included the measures of interest. The mean age of participants in this sample was 21.40 (SD = 2.18), 129 (66.8%) were male, 134 (69.4%) were current students (undergraduate, graduate, or professional school), and 149 (77.2%) identified as White. Remaining participants identified as African-American (9.8%), multiracial (4.1%), Asian-American (2.5%), American Indian (.5%), or other racial/ethnic group (3.6%), with 2.1% declining to report their race/ethnicity. At baseline, 82.4% of participants met DSM-IV-TR criteria for a lifetime alcohol use disorder, with 60.1% meeting criteria for alcohol dependence and 22.3% meeting criteria for alcohol abuse only. Means, SDs, and ranges for all study variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range | Valid N (of 193) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinks per Week | 28.29 | 18.78 | 1.38–131.85 | 193 |

| DASS Anxiety Score | 4.05 | 1.31 | 0–39 | 185 |

| UPPS Negative Urgency Score | 2.37 | .47 | 1–4 | 189 |

| Coping Motives | 8.72 | 5.25 | 0–20 | 187 |

| YAACQ Total Score | 20.58 | 9.68 | 0–48 | 190 |

| YAACQ Social/Interpersonal Consequences | 3.16 | 1.79 | 0–6 | 190 |

| YAACQ Impaired Control | 3.34 | 1.76 | 0–6 | 190 |

| YAACQ Diminished Self-Perception | 1.53 | 1.49 | 0–4 | 190 |

| YAACQ Poor Self-Care | 3.01 | 2.45 | 0–4 | 190 |

| YAACQ Risky Behavior | 2.67 | 1.94 | 0–8 | 190 |

| YAACQ Academic/Occupational Consequences | 1.29 | 1.38 | 0–5 | 190 |

| YAACQ Physiological Dependence Symptoms | .98 | .88 | 0–4 | 190 |

| YAACQ Blackout Drinking | 4.59 | 2.08 | 0–7 | 190 |

Procedure

The Yale School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the clinical trial from which participants were drawn. All participants provided written informed consent before completing survey measures. Adults ages 18–25 from the community were invited to participate in the study, which was advertised in local newspapers, on television, online, and via flyers. The study was not explicitly advertised as a clinical trial, as participants were not required to be actively seeking treatment for alcohol problems in order to participate, but recruitment materials clearly stated that counseling and medication for drinking reduction would be involved. Compensation of up to $500 was provided for enrolled participants.

Measures

Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

The DASS is a 42-item measure that assesses past-week depression, anxiety, and stress to obtain an estimate of typical symptom levels. The anxiety subscale was the only scale utilized in the current study. The DASS anxiety subscale consists of 14 items, but for the current study only 13 items were utilized as 1 item was missing due to an administrative error. For the 13 included items on the anxiety subscale, internal consistency was good (α = .87).

UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Lynam et al., 2006)

The UPPS-P is a 59-item measure that assesses different facets of impulsivity, including 12 items assessing negative urgency. Negative urgency is the tendency to become disinhibited in the presence of negative affect (Cyders & Smith, 2008). Only the negative urgency subscale was utilized in the current study. Internal consistency for this subscale was acceptable (α = .76).

Daily Drinking Questionnaire - Revised (DDQ-R; Collins et al., 1985; Kruse et al., 2005)

A revised version of the DDQ was used to assess frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption. Participants were asked to report the number of drinking days over the past 3 months for every day of the week (i.e., how many times a participant drank on a Monday in the last 3 months) as well as the average number of drinks consumed on each drinking day of the week over the past 3 months. We multiplied the total number of drinking days by the average number of drinks per drinking day to estimate the total number of drinks consumed in the 3-month period prior to the intake assessment.

Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read et al., 2006)

The YAACQ is a 48-item measure of alcohol-related problems containing 8 different subscales including social/interpersonal, academic/occupational, risky behavior, impaired control, poor self-care, diminished self-perception, blackout drinking, and physiological dependence. Given that the YAACQ is comprised of dichotomous yes/no items, tetrachoric (rather than Pearson) correlations were computed between all items within each subscale in Mplus using the weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) (J. Read, personal communication March 28, 2013). These correlations were used in calculating alpha values. Alpha values for the YAACQ subscales were in the acceptable to excellent range, with values from .73 (physiological dependence) to .91 (diminished self-perception).

Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper et al., 1992)

The DMQ is a self-report measure that assesses the extent to which individuals consume alcohol for the purposes of reducing/alleviating negative affect (coping motives), facilitating social interaction (social motives), and enhancing positive affect (enhancement motives). These motives are not mutually exclusive (i.e., a participant may endorse frequently drinking for all 3 purposes). Internal consistencies were in the acceptable to good range (α = .76 for social motives, α = .85 for coping motives, and α = .80 for enhancement motives) in the current sample.

Data Analytic Plan

Before conducting primary analyses, distributions of all variables were examined for non-normality. We also examined correlations among predictors and collinearity diagnostics to ensure that there were no significant problems with multicollinearity.

Primary Analyses – Mediated Moderation

Primary analyses tested the mediated moderation hypothesis outlined previously. Mediated moderation is present when the effect of the independent variable (anxiety in the current study) on the mediating variable (coping motives) is moderated by a third variable (the moderator, negative urgency), and the mediating variable significantly predicts the criterion variable (alcohol problems). If these two criteria are met, the relative magnitudes of the indirect effects of the independent variable on the outcome (through the mediating variable) are examined at different levels of the moderating variable (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). To test our conceptual model, we constructed a series of models using Preacher and colleagues’ (2007) MODMED routine in Mplus, which is specifically designed to test mediated moderation (and moderated mediation) hypotheses. These models simultaneously test predictors of the mediator (coping motives) and outcome (alcohol problems), as well as moderated indirect effects of the independent variable on the outcome variable through the mediating variable. Of central importance in the current study, we hypothesized that a) anxiety would be a stronger predictor of the mediator (coping motives) at higher levels of negative urgency (moderation), b) stronger coping motives would predict more alcohol problems, and c) indirect effects of anxiety on alcohol problems through coping motives would be stronger at higher levels of negative urgency (mediated moderation). If the interaction between anxiety and negative urgency significantly predicted coping motives, we examined potential indirect effects of anxiety on alcohol problems (through coping motives) at the mean of negative urgency, 1 standard deviation below the mean of negative urgency, and 1 standard deviation above the mean of negative urgency. We similarly decomposed the interaction if it directly predicted alcohol problems. If the interaction was not significant, we removed the interaction term from the model and examined indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency (through coping motives) on alcohol problems. We tested eight separate models, each with a different YAACQ subscale as the outcome (all tests with YAACQ subscales as outcomes were Bonferroni-corrected to a significance threshold of p < .00625 to account for multiple comparisons). Analyses utilized the full sample size by using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation and also employed bootstrapping re-sampling methods, ensuring robustness to any non-normality remaining after transformation of variables. We used bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals generated in Mplus to test moderated indirect effects given the asymmetric distribution of products of coefficients (MacKinnon et al., 2004). It should be noted that, although we tested a theory-based causal model, we were not able to determine the true temporal ordering of relations among the study variables given the cross-sectional nature of the data.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Both DDQ-R total drinks (skewness statistic = 9.8) and scores on the DASS anxiety subscale (skewness statistic = 9.36) exhibited significant positive skew and were therefore log-transformed. Transformations improved the distributions substantially (skewness statistics of -3.25 and 1.30 for DDQ-R total drinks and DASS anxiety respectively). Neither the magnitude of the correlations among study variables (the largest correlation was between DASS anxiety and UPPS negative urgency: r = .345, p < .001), nor the collinearity diagnostics (Variance Inflation Factors values < 2 and tolerance values > .8) identified any potential problems with multicollinearity (see Table 2 for correlations among study variables).

Table 2.

Correlations among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. Anxiety | .113 | - | |||||||||||

| 3. Negative Urgency | −.013 | .345 | - | ||||||||||

| 4. Coping Motives | −.121 | .274 | .267 | - | |||||||||

| 5. YAACQ Total Score | −.004 | .361 | .544 | .383 | - | ||||||||

| 6. YAACQ Social/Interpersonal Consequences | .025 | .318 | .426 | .279 | .746 | - | |||||||

| 7. YAACQ Impaired Control | −.041 | .215 | .351 | .349 | .686 | .424 | - | ||||||

| 8. YAACQ Diminished Self-Perception | −.049 | .163 | .372 | .379 | .675 | .497 | .544 | - | |||||

| 9. YAACQ Poor Self-Care | −.047 | .349 | .414 | .360 | .723 | .344 | .463 | .494 | - | ||||

| 10. YAACQ Risky Behavior | .076 | .307 | .448 | .194 | .767 | .587 | .388 | .376 | .386 | - | |||

| 11. YAACQ Academic/Occupational Consequences | −.020 | .225 | .401 | .137 | .658 | .388 | .306 | .339 | .466 | .487 | - | ||

| 12. YAACQ Physiological Dependence Symptoms | −.063 | .318 | .291 | .396 | .626 | .430 | .473 | .309 | .407 | .471 | .339 | - | |

| 13. YAACQ Blackout Drinking | .056 | .135 | .314 | .112 | .679 | .505 | .280 | .250 | .306 | .560 | .418 | .354 | - |

Note: Bolded correlations are statistically significant (p < .05).

Mediated Moderation Analysis

When the full mediated moderation model was tested using MODMED, the first prerequisite for mediated moderation was not met. Specifically, the interaction between anxiety and negative urgency in the prediction of coping motives was not significant (b = -.289, SE = 2.309, p = .90). Thus, any moderated effect of anxiety on alcohol-related problems was not mediated through coping motives. However, we did find an interaction between anxiety and negative urgency in the prediction of physiological dependence symptoms on the YAACQ (b = 1.01, SE = .312, p = .001), even when accounting for the effects of coping motives on this outcome1.

Thus, we examined simple slopes for the effect of anxiety on physiological dependence symptoms at the mean and at 1 standard deviation above and below the mean of negative urgency. These analyses revealed that the relationship between anxiety and physiological dependence symptoms was significant at average to high levels of negative urgency (b = .444, SE = .159, p = .005 at the mean of negative urgency; b = .855, SE = .215, p < .001 at 1 SD above the mean of negative urgency), but not at low levels of negative urgency (b = .033, SE = .187, p = .861). For a graphical depiction of the interaction, see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Anxiety by Negative Urgency Interaction Predicting Physiological Dependence Symptoms

Indirect Effects of Anxiety and Negative Urgency on Alcohol-Related Consequences

Although the first prerequisite for mediated moderation was not met (lack of interaction between anxiety and negative urgency in predicting coping motives), the second requirement (coping motives predicting YAACQ subscales) was met for 4 of the 8 YAACQ subscales. Coping motives significantly predicted the physiological dependence (b = .045, SE = .011, p < .001), impaired control (b = .079, SE = .025, p = .002), poor self-care (b = .102, SE = .034, p = .003), and diminished self-perception (b = .087, SE = .020, p < .001) subscales even after Bonferroni correction. In addition, zero-order correlations (see Table 2) showed significant correlations between coping motives and both anxiety and negative urgency, suggesting possible indirect effects of both anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol problems through coping motives, as has been found in prior studies (Adams et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2001). Since prior studies have not examined indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol problems within a single model, we conducted a post-hoc analysis to determine whether there were independent indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol problems through coping motives. In this model, we removed all interactions and tested indirect effects using the MODEL INDIRECT command in Mplus.

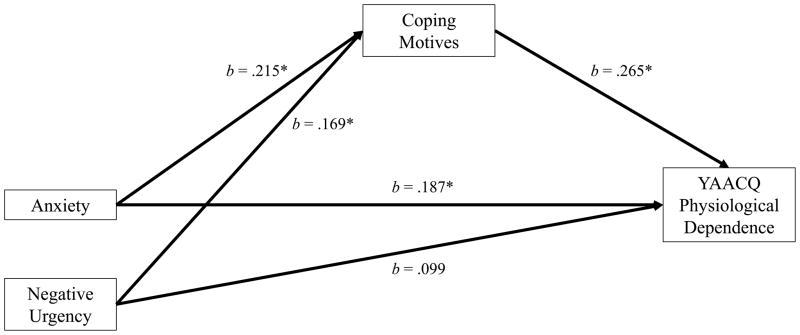

Tests of indirect effects were conducted using bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals, with confidence intervals not containing the value of zero indicating significant indirect effects. These analyses identified significant indirect effects of both anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol problems through coping motives2. Higher levels of anxiety were indirectly associated with higher scores on physiological dependence symptoms (CI .035 - .271), impaired control (CI .062 - .494), poor self-care (CI .059-.638), and diminished self-perception (CI .062-.477) through stronger coping motives. Similarly, higher levels of negative urgency were indirectly associated with greater physiological dependence symptoms (CI .013-.211), impaired control (CI .015-.362), poor self-care (CI .022-.528), and diminished self-perception (CI .026-.378) through stronger coping motives. See Figure 3 for a depiction of the indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency on YAACQ physiological dependence symptoms.

Figure 3.

Direct and Indirect Effects of Anxiety and Negative Urgency on YAACQ Physiological Dependence Symptoms

Note: This model also included gender and alcohol consumption as covariates. *p < .05

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to test a mediated moderation model in which it was hypothesized that the indirect effect of anxiety on alcohol problems through coping motives would be stronger among those with higher levels of negative urgency. Although we did not find evidence supporting mediated moderation, we did find evidence for a direct moderated effect of anxiety on physiological dependence symptoms as well as independent indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol-related consequences (4 of 8 YAACQ subscales) through coping motives. These findings support the importance of examining the combination of anxiety and negative urgency when assessing risk for alcohol-related problems.

Our demonstration of indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol-related problems through coping motives is consistent with prior studies (Adams et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2001). However, to our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating these effects when considering both variables in the same model. This suggests that the indirect effects of these variables may be additive rather than overlapping, although this cannot be concluded with certainty given the cross-sectional nature of the data. Future studies should investigate the possibility that elevated anxiety and negative urgency might independently increase risk for alcohol-related problems through stronger coping motives.

Perhaps the most novel finding of this study was that negative urgency was a significant moderator of the direct effect of anxiety on physiological dependence symptoms (again, this effect was not mediated by coping motives). The nature of this interaction suggests that as negative urgency increases, the association between anxiety and physiological dependence symptoms becomes stronger. Negative urgency is defined as the predisposition to become behaviorally dysregulated (behave impulsively) when experiencing negative affect; thus, this effect makes some intuitive sense. If one frequently experiences negative affect, a predisposition to become dysregulated in the face of negative affect would be realized more frequently and would have a greater effect on behavior. Thus, behavioral dysregulation among individuals high in anxiety may manifest in drinking behaviors that ultimately increase risk for symptoms of physical dependence on alcohol. Again, future longitudinal studies are needed to further test this hypothesis, as it implies transactional changes over time.

Although interactive effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol-related problems were observed, the lack of mediation by coping motives was surprising, especially given separate indirect effects of both anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol-related problems operating through coping motives. One possible explanation for the failure to find this effect is a lack of power, as testing interactions requires greater power than testing main effects. Although our study was well-powered to detect an interaction effect of medium size (1-β = .99 for an effect equivalent to an r-squared value of .10), we would have been under-powered to detect a small effect (1-β = .28 for an effect equivalent to an r-squared value of .01), limiting the ability of the current study to determine whether such an interaction exists.

However, if the interactive effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol-related problems do not operate through coping motives, it leaves remaining questions about other possible mechanisms. The concept of “impaired control” over drinking (Heather et al., 1993; Leeman et al., 2014) is appealing as a potential mechanism. Impaired control constitutes “a breakdown of an intention to limit consumption in a particular situation” (Heather et al., 1993, p. 701). Difficulty limiting alcohol use may manifest itself as a diminished ability to avoid alcohol use altogether or to control alcohol use once initial consumption has begun (Heather et al., 1993; Kahler et al., 1995). If those with high negative urgency are particularly likely to experience impaired control over drinking, this could help explain the results of the present study. Supporting this idea, a recent study found that impaired control partially mediated relationships between negative urgency and both alcohol use and related problems among young adults (Patock-Peckham et al., 2011). Similarly, the related construct of unplanned drinking has been shown to partially mediate the effect of negative urgency on alcohol-related problems in young adults (Pearson & Henson, 2013). Although it seems plausible that impaired control and/or unplanned drinking might mediate the interactive effect of anxiety and negative urgency on drinking outcomes, future studies are needed to empirically evaluate this hypothesis.

Although we did not find evidence to support our mediated moderation model, our findings of direct moderated effects of anxiety and separate indirect effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol-related problems have potential implications for conceptualizing and treating alcohol use disorders in populations that are high in anxiety, negative urgency, or both. The notion that elevated anxiety puts an individual at risk for alcohol problems via increased coping motives is not new (Stewart et al., 2001), and this particular risk mechanism is already targeted in some interventions for populations at risk for coping-related drinking (e.g., Kushner et al., 2013). Similarly, negative urgency has previously been shown to increase risk for alcohol use and problems indirectly through coping motives (Adams et al., 2012), so identifying negative urgency as a risk factor is also not unique to the current study. However, our finding that anxiety and negative urgency exerted independent indirect effects on alcohol-related consequences is important as it suggests that addressing 1 of these 2 risk factors may not impact risk associated with the other. In addition, the observed interaction effect is a novel finding and suggests a separate mechanism that may warrant attention in conceptualization and treatment of alcohol use disorders in this population.

Although the findings of the current study have implications for our understanding of relationships among negative affect, impulsivity, and alcohol-related problems, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. First and foremost, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits our ability to apply true temporal tests of our mediation hypotheses and to determine the direction of effects (e.g., it is possible that anxiety symptoms are a result of alcohol-related problems or that the relationship is reciprocal). However, previous studies have reported longitudinal effects of anxiety symptoms on future alcohol-related problems (e.g., Guo et al., 2001) as well as longitudinal effects of negative urgency on future alcohol consumption (through coping motives) (Settles et al., 2010), supporting the proposed direction of effects in the current study. Nevertheless, future studies should examine the influences of negative urgency and anxiety on alcohol-related problems using prospective data.

Second, our measure of anxiety (the DASS) uses a past-week timeframe, which may be short enough to capture variability in acute anxiety as well as more typical levels of anxiety. However, typical anxiety as measured by the DASS is still clearly conceptually distinct from a measure of momentary anxiety (as in Simons et al., 2010), as it does not specifically assess anxiety symptoms occurring at the present time or in response to a particular environmental stressor. Nonetheless, future studies of the relationship between anxiety, negative urgency, and alcohol outcomes would benefit from the use of multiple methods to assess anxiety. An additional potential limitation is that our sample was comprised of high-risk young adult drinkers. Although there are several advantages to this sample, we cannot be certain that the results would generalize to all young adult drinkers. It may be that the proposed risk factors are only operative in individuals that already evidence some level of problematic or hazardous drinking. Finally, the measures used in this study all relied on self-report. Future studies could benefit from efforts to assess these constructs using multiple methods, including objective measures.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the present study yielded novel findings with potential implications for prevention and intervention approaches. While we did not find support for our mediated moderation model, we identified multiple potential pathways to risk for alcohol-related problems among individuals high in both anxiety and negative urgency. These putative pathways to risk for alcohol use disorders may represent important targets for intervention and prevention in this population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01-AA016621; K01 AA019694; KO5 AA01471; K23 AA020000) and by the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

In order to ensure that the observed interaction was not an artifact of an un-modeled quadratic relationship between either of the predictor variables and the outcome (Lubinski & Humphreys, 1990), quadratic terms for anxiety and negative urgency were tested as predictors of alcohol problems. Neither of these quadratic terms were statistically significant nor did they explain a greater proportion of variance in the outcome variable compared to the interaction term. Therefore, the observed interaction was treated as valid.

Supporting our hypothesis that indirect effects would be specific to coping motives, we found that anxiety, negative urgency, and their interaction failed to predict either social or enhancement motives. Thus, coping motives emerged as a unique mediator of the independent effects of anxiety and negative urgency on alcohol problems.

References

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, Milich R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addict Behav. 2012;37:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Todd M, Conner TS, Tennen H. Drinking to cope with negative moods and the immediacy of drinking within the weekly cycle among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:313–322. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell TM, Rodgers B, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Jacomb PA, Korten AE, Lynskey MT. Patterns of association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adults. Addiction. 2002;97:583–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Alcoholism: theory, problem and challenge. II. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychol Assess. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Cyders MA. Mediation–moderation analysis of problematic alcohol use: the roles of urgency, drinking motives, and risk/benefit perception. Addict Behav. 2012;37:880–883. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demartini KS, Carey KB. The role of anxiety sensitivity and drinking motives in predicting alcohol use: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2001;54:754–762. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Bonin M, Hope DA. The role of drinking motives in social anxiety and alcohol use. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:991–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Bacon AK, Garcia TA. Drinking motives as mediators of social anxiety and hazardous drinking among college students. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:133–145. doi: 10.1080/16506070802610889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Tebbutt JS, Mattick R, Zamir R. Development of a scale for measuring impaired control over alcohol consumption: a preliminary report. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 1993;54:700–709. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Epstein EE, McCrady BS. Loss of control and inability to abstain: the measurement of and the relationship between two constructs in male alcoholics. Addiction. 1995;90:1025–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90810252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyadi KA, King KM. Urgency and negative emotions: evidence for moderation on negative alcohol consequences. Pers Indiv Differ. 2011;51:635–640. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Karyadi KA, Luk JW, Patock-Peckham JA. Dispositions to rash action moderate the associations between concurrent drinking, depressive symptoms, and alcohol problems during emerging adulthood. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:446–454. doi: 10.1037/a0023777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse MI, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Improving accuracy of QF measures of alcohol use: disaggregating quantity and frequency. Poster presented at the 28th annual meeting of the research Society on Alcoholism; Santa Barbara, CA. Jun, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Maurer EW, Thuras P, Donahue C, Frye B, Menary KR, Hobbs J, Haeny AM, Van Demark J. Hybrid cognitive behavioral therapy versus relaxation training for co-occurring anxiety and alcohol disorder: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:429–442. doi: 10.1037/a0031301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Beseler CL, Helms CM, Patock–Peckham JA, Wakeling VA, Kahler CW. A brief, critical review of research on impaired control over alcohol use and suggestions for future studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:301–308. doi: 10.1111/acer.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Hove MC, Whiteside U, Lee CM, Kirkeby BS, Oster-Aaland L, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Fitting in and feeling fine: conformity and coping motives as mediators of the relationship between social anxiety and problematic drinking. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:58–67. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubinski D, Humphreys LG. Assessing spurious “moderator effects”: illustrated substantively with the hypothesized (“synergistic”) relation between spatial and mathematical ability. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:385–393. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, Cyders MA. The UPPS-P: assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar Behav Res. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A, Burgess ES, Clark M, Zvolensky MJ, Brown RA. Anxiety sensitivity, self-reported motives for alcohol and nicotine use, and level of consumption. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:165–180. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Corbin WR, Leeman RF, DeMartini KS, Fucito LM, Ikomi J, Kranzler HR. Reduction of alcohol drinking in young adults by naltrexone: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of efficacy and safety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:e207–e213. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, King KM, Morgan-Lopez AA, Ulloa EC, Moses JMF. Gender-specific mediational links between parenting styles, parental monitoring, impulsiveness, drinking control, and alcohol-related problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:247–258. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, Henson JM. Unplanned drinking and alcohol-related problems: a preliminary test of the model of unplanned drinking behavior. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:584–595. doi: 10.1037/a0030901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar Behav Res. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Keough ME. Anxiety sensitivity as a prospective predictor of alcohol use disorders. Behav Modif. 2007;31:202–219. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schry AR, White SW. Understanding the relationship between social anxiety and alcohol use in college students: a meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2690–2706. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders M, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psych Addict Behav. 2010;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addict Behav. 2010;35:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MN, Bush JA, Palmer MA. An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2005;66:459–469. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Peterson JB, Pihl RO. Anxiety sensitivity and self-reported alcohol consumption rates in university women. J Anxiety Disord. 1995;9:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Taylor S, Baker JM. Gender differences in dimensions of anxiety sensitivity. J Anxiety Disord. 1997;11:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;31:157–171. [Google Scholar]