Abstract

Background

Few epidemiologic studies have examined a full range of adolescent psychiatric disorders in the general population. The association between psychiatric symptom clusters (PSCs) and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders (AUDs) among adolescents is not well understood.

Methods

This study draws upon the public-use data from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, including a study sample of 19,430 respondents ages 12 to 17. Logistic regression and exploratory structural equation modeling assess the associations between PSCs and DSM-IV AUDs by gender. The PSCs are based on brief screening scales devised from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Predictive Scales.

Results

Several PSCs were found to be significantly associated with DSM-IV AUDs, including separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder among both genders, and panic disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder among females. Consistent with the literature, the analysis of PSCs yields three factors identical for both genders—two internalizing factors (fear and anxiety–misery) and one externalizing factor. Adolescents who scored higher on the externalizing factor tended to have higher levels of the AUD factor. Female adolescents who scored higher on the internalizing misery factor and lower on the internalizing fear factor also tended to have higher levels of the AUD factor.

Conclusion

The associations that we found between PSCs and AUDs among adolescents in this study are consistent with those found among adults in other studies, although gender may moderate associations between internalizing PSCs and AUDs. Our findings lend support to previous findings on the developmentally stable associations between disruptive behaviors and AUDs among adolescents as well as adults in the general population.

Keywords: Alcohol Use Disorders, Psychiatric Symptom Clusters, Epidemiology, Adolescents, Structural Equation Modeling

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiologic studies of adults in the general population have documented the prevalence and co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol use disorders (AUDs) with other mental health conditions, including anxiety, mood, and personality disorders (Grant et al., 2004a; 2004b; Kessler et al., 1997). Many symptoms of psychiatric disorders begin during childhood or adolescence. Estimates from an adult national sample (Kessler et al., 2005) indicated that nearly half of all adults with psychiatric disorders reported onset by age 14. Despite the documented association between childhood/adolescent and adult mental health problems, few epidemiologic studies have evaluated the prevalence of adolescent psychiatric disorders in the general population. Shaffer and colleagues (1996) reported that one-third of youth ages 9 to 17 met DSM diagnostic criteria for any psychiatric disorder (i.e., anxiety and mood disorders, disruptive behavior, and substance use disorders [SUDs]). However, their samples were small and not representative of the U.S. population. An epidemiologic survey (Teen Health 2000) interviewing 4,175 youth ages 11 to 17 in a large metropolitan area (Roberts et al., 2007a) revealed that 11% met DSM-IV criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders in the past year. The most prevalent disorders included anxiety disorder (agoraphobia) (6.9%); disruptive behaviors (conduct disorder) (6.5%); and SUDs (5.3%). While female adolescents had higher odds for mood and anxiety disorders, male adolescents had higher odds for disruptive behavior and SUDs.

Recent findings from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) indicated that the lifetime prevalence for any psychiatric disorder in U.S. adolescents was 51%, and that the prevalence for severe impairment was 22% (Merikangas et al., 2010). In this nationally representative sample of 10,123 adolescents ages 13 to 17, the most common lifetime mental conditions were anxiety disorders (31%), behavior disorders (19%), mood disorders (14%), and SUD (11%). In an earlier study, Chen, Killeya-Jones, and Vega (2005) provided national estimates of the prevalence of psychiatric symptom clusters (PSCs) based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) Predictive Scales (DPS) (Shaffer et al., 1996) among 19,430 adolescents (12–17 years) from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA). Lucas and colleagues (2001) devised the DPS screen scales based on the DISC-2.3 for the most common mental disorders among children and adolescents, including anxiety disorders, affective disorders, disruptive disorders, and SUDs. The most prevalent types of past-year PSCs were anxiety disorders (40%), mood (10%), disruptive behavior (36%), and substance use (10%) disorders. Compared with males, females reported higher rates of anxiety and affective disorders, but both genders had similar rates for disruptive behavior and SUDs. The prevalence rates of PSCs were slightly higher for SUDs and affective disorders and lower for anxiety disorders among older adolescents. There were significant gender-by-age interactions, indicating that younger females had higher risk for any anxiety, mood, or behavioral clusters.

Although the prevalence of AUDs among adolescents has been well documented in national surveys (Eaton et al., 2006; Harford et al., 2005), fewer national studies have examined associations between AUDs and other psychiatric disorders. Chan and colleagues (2008) reported associations between SUDs and other mental conditions among 4,939 adolescents presenting for treatment in multisite studies. The prevalence of AUDs and other mental health problems in the past year was 21.7% for those younger than age 15 and 27.8% for those ages 15 to 17. Prevalence estimates for these two age groups were 13.9% and 18.1% for alcohol abuse, and 7.8% and 9.7% for alcohol dependence, respectively. Drawing upon the Teen Health 2000 survey, Roberts and colleagues (2007b) reported that the risk for alcohol abuse and dependence was significantly increased by mood disorders (odds ratio: 7.8 and 12.3, respectively) and by conduct disorder/oppositional defiant disorder (CD/ODD) (odds ratio: 7.9 and 12.6, respectively); the risk for alcohol dependence was increased by anxiety disorders (odds ratio: 2.8). There was no significant association between AUD and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The high co-occurrence of mental health problems has prompted investigations of the underlying structure of these disorders. Factor analytic studies in adult populations have identified a three-factor model that includes one externalizing factor represented by antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and alcohol and drug dependence, and two correlated internalizing factors labeled “anxiety–misery” (major depression, dysthymia, and generalized anxiety) and “fear” (social phobia, specific phobia, agoraphobia, and panic) (Krueger, 1999; Krueger et al., 1998; Krueger and Markon, 2006; Vollebergh et al., 2001). These externalizing and internalizing factors reflect underlying vulnerabilities with both genetic and environmental influences (Kendler et al., 2003). Studies on adolescent and young-adult populations have indicated overall consistency for these three dimensions, despite some variation according to the diagnosis and age composition of the samples (Beesdo-Baum et al., 2009; Farmer et al., 2009; Kessler et al., 2012). In the NCS-A (Kessler et al., 2012), the fear factor included social and specific phobia, agoraphobia, and panic disorders; the anxiety–misery factor included separation anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive episode/dysthymia, and generalized anxiety disorder. The externalizing factor included ODD, CD, eating disorder, and alcohol and drug abuse and dependence.

Building on the earlier study by Chen and colleagues (2005) using the predictive scales to assess psychiatric problems (Lucas et al. 2001), our study further analyzes this NHSDA 2000 sample to examine the association between PSCs and DSM-IV AUDs among adolescents in the United States. In the analysis, we included the DSM-IV AUD diagnoses (abuse and dependence) in order to provide comparisons with the existing literature in this area. In addition, because of concerns regarding the abuse/dependence distinction as well as the new dimensional approach of DSM-5 (Gelhorn et al., 2008), we further included a more in-depth analysis of the DSM-IV AUD criteria as a single latent variable. We based our hypothesis on current literature that the structure underlying PSCs will match the internalizing–externalizing dimensions for psychiatric disorders reported in other studies and that both internalizing and externalizing PSCs are associated with AUDs. A literature review of 15 studies by Armstrong and Costello (2002) concluded that the overall pattern of temporal sequence is for psychiatric disorders, particularly depression (Costello et al., 1999) and anxiety (Costello et al., 2003), to precede substance use disorders. The progression from early disruptive behaviors to substance use disorders also has been replicated in several studies (Cohen et al., 2007; Fergusson et al., 2005; Hayatbakhsh et al., 2008; Sung et al., 2004). Based on the temporal ordering suggested in these studies particularly in adolescent populations, internalizing-externalizing PSC factors are assumed to be antecedents to the underlying AUD factor in the statistical models of our analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Design

Our study was based on the public-use data file from the NHSDA 2000, the only survey in this series of annual surveys that included a broad coverage of psychiatric symptoms in the United States. The NHSDA 2000 was part of a 5-year (1999–2003) stratified, multistage sample design, with 71,704 respondents representing the household and noninstitutionalized group-quarters population ages 12 and older of the 50 States and District of Columbia. Young people ages 12 to 25 were oversampled. The public-use file has only 58,680 records due to a subsampling step used in the disclosure protection procedures. More details on the sample design and implementation can be found in the report on results from the NHSDA 2000 published by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2005). Our study included 19,430 respondents (9,856 males and 9,574 females) ages 12 to 17.

Measures

In NHSDA 2000, DSM-IV AUD diagnoses were assessed by questions related to specific symptoms occurring during the past 12 months. To receive a DSM-IV alcohol dependence diagnosis, respondents were required to meet at least three of the seven diagnostic criteria for dependence in the 12 months preceding the survey. To receive a DSM-IV alcohol abuse diagnosis, respondents had to meet one of the four diagnostic criteria for abuse in the 12 months preceding the survey (American Psychiatric Association 1994).

Measures of the psychiatric symptoms included in the NHSDA 2000 are based on the DPS developed by Lucas and colleagues (2001). The cutoff point of the DPS for each dichotomized symptom cluster is based on prior analysis (Lucas et al. 2001). Although these scales do not provide actual DSM-IV diagnoses, they can identify groups at high risk for the respective disorders. Item sensitivity was above 0.89 for most items (ranging from 0.37 to 1.00), and specificity was above 0.90 for most items (ranging from 0.72 to 0.98) (Chen et al., 2005). We included the following 13 psychiatric clusters in our study: social phobia (SOPH), separation anxiety (SAD), agoraphobia (AGOR), panic disorder (PANIC), generalized anxiety (GAD), specific phobia (SIPH), obsessive-compulsive (OCD), major depression (MDD), mania, (MAN), ADHD, ODD, CD, and eating disorder (EAT). We excluded elimination disorder because of its small number of cases (<.02%).

Additional variables included gender (males compared with females), age in years (12 to 17), and race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic Black, Native American, Asian, and Hispanic, with Non-Hispanic White as the referent group).

Statistical Analysis

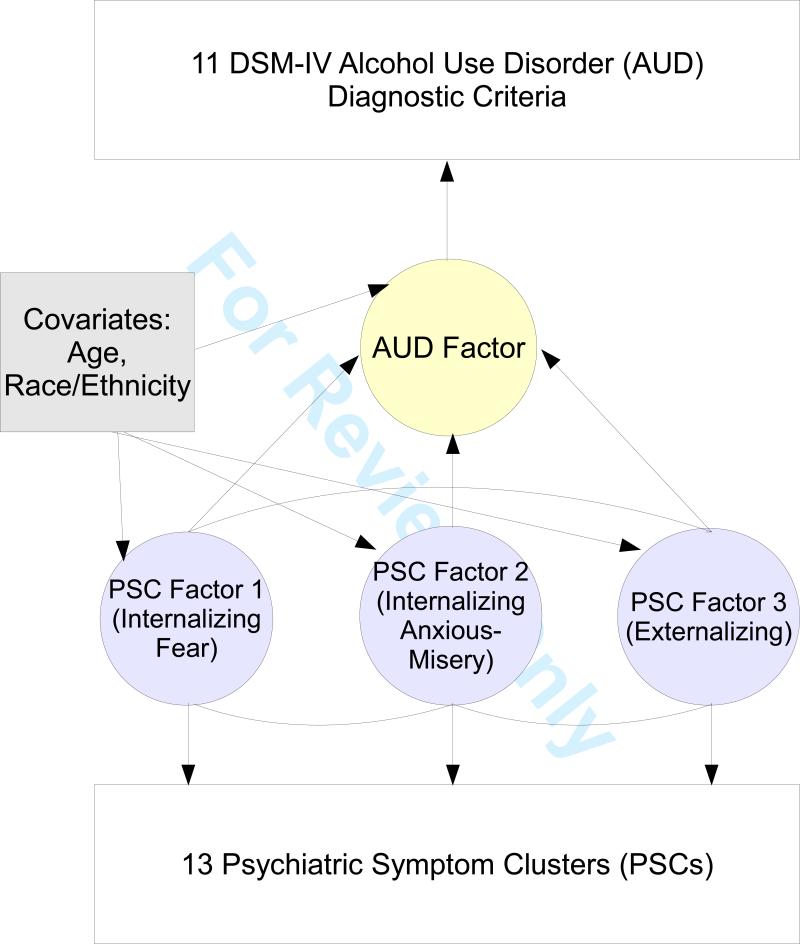

Cross-tabulations were used to calculate the 12-month prevalence of PSCs by DSM-IV AUD status—no AUD, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, or any AUD—and gender. Logistic regression was used to estimate the relative odds of whether adolescents having a specific PSC, with and without other PSCs, would have a DSM-IV AUD. For each logistic regression, the model includes a PSC-by-gender interaction term besides the main effect terms to assess the gender difference for the male-to-female ratio. We used gender-specific correlation matrix and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine the structure underlying psychiatric disorders. Based on review of the literature, we explored one- to three-factor models for the 13 PSCs and assessed model fit statistically with a chi-square difference test. We used exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), which integrates EFA into structural equation modeling (Asparouhov and Muthén, 2009; Marsh et al., 2009), to assess relationships between the PSC factors and a latent AUD factor based on DSM-IV criteria. Compared with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), EFA is often used in the absence of a strong theoretical model. Because there are few prior studies on adolescent populations, we opted for EFA instead of CFA to yield the most optimal fit to the empirical data. In addition to the PSCs and covariates such as age and race/ethnicity, we included a single latent factor representing continuous levels of AUD based on the 11 DSM-IV AUD diagnostic criteria in the model. In the structural part of the model, the PSC latent factors were regressed on the covariates; the AUD latent factor was regressed on each of the PSC latent factors as well as the other covariates. Thus, as illustrated in Figure 1, the model includes two sets of relationships: (1) those between the AUD symptom criteria/PSCs and their respective latent factors (the measurement part), and (2) those between the latent factors and the covariates and between the PSC latent factors and the AUD latent factor (the structural part).

Figure 1.

Path Diagram of the Exploratory Structural Equation Model

Note that Figure 1 does not specify the relationship between the covariates and the AUD symptom criteria/PSCs (the direct effects). Even though the preliminary analyses that we conducted separately for each gender group found some significant direct effects, removing them from the models did not affect the overall fit. Specifically, the fit measures and coefficients of the measurement and structural models were nearly identical with or without the specification of five direct effects for males and five direct effects for females. For this reason, we did not consider direct effects in the multiple group analysis when testing gender differences for measurement invariance. For multiple group analysis, measurement invariance is an important requisite to establish that the same underlying construct is measured across specified groups. We tested the presence of measurement invariance for intercepts (thresholds) and factor loadings by comparing the CONFIGURAL invariance (factor loadings and thresholds free across groups, residual variances fixed at one in all groups, and factor means fixed at zero in all groups) with the METRIC/SCALAR invariance (factor loadings and thresholds constrained to be equal across groups, residual variances fixed at one in one group and free in the other groups, and factor means fixed at zero in one group and free in the other groups).

The model was estimated by a robust, weighted, least-squares estimator with a geomin rotation. Model fit indices included comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error approximation (RMSEA). The following cutoff values were used as indicators of good fit: CFI or TLI > 0.95; RMSEA < 0.06 (Bentler, 1990). We conducted our analyses using the statistical modeling program Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Mplus allows for specifications of sampling stratification, clustering, and weights in ESEM models and takes into account the three sampling features for parameter estimation as well as standard error and model fit calculations.

RESULTS

The prevalence in the past year for alcohol dependence was similar between male adolescents (1.84%) and female adolescents (1.89%), as was that for alcohol abuse (male, 3.35%; female, 3.25%). As shown in Table 1, in each gender group, the prevalence of each PSC was higher among those with alcohol dependence than those with alcohol abuse (Table 1). For males with alcohol dependence, the most prevalent cluster was ODD (54.9%), followed by CD (48.0%), MDD (31.2%), and ADHD (26.3%). For females with alcohol dependence, the most prevalent cluster was ODD (61.7%), followed by MDD (54.1%), GAD (46.9%), CD (43.6%), and ADHD (39.7%).

Table 1.

Twelve-month prevalence (%) of psychiatric symptom clusters (PSCs), by DSM-IV alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and gender, among adolescents ages 12–17, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 2000

| PSCa | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Alcohol Dependence | Alcohol Abuse | No AUD Diagnosis | All | Alcohol Dependence | Alcohol Abuse | No AUD Diagnosis | |

| N=9856 | N=173 | N=344 | N=9339 | N=9574 | N=183 | N=329 | N=9062 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| SOPH | 14.7 | 19.2 | 16.3 | 14.5 | 18.4 | 26.2 | 19.7 | 18.1 |

| SAD | 5.5 | 10.7 | 7.2 | 5.4 | 9.1 | 16.2 | 5.7 | 9.1 |

| AGOR | 5.9 | 10.4 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 12.9 | 22.9 | 13.6 | 12.7 |

| PANIC | 3.8 | 12.2 | 5.9 | 3.6 | 8.3 | 28.6 | 15.9 | 7.6 |

| GAD | 11.4 | 21.3 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 18.9 | 46.9 | 36.4 | 17.7 |

| SIPH | 8.4 | 14.0 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 18.9 | 32.5 | 22.4 | 18.5 |

| OCD | 11.8 | 20.5 | 15.9 | 11.5 | 17.1 | 41.1 | 27.3 | 16.2 |

| MDD | 7.9 | 31.2 | 14.6 | 7.2 | 16.5 | 54.1 | 35.2 | 15.1 |

| MAN | 2.7 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 12.3 | 5.6 | 3.4 |

| ADHD | 13.8 | 26.3 | 18.3 | 13.4 | 15.6 | 39.7 | 29.2 | 14.7 |

| ODD | 27.9 | 54.9 | 49.5 | 26.6 | 26.2 | 61.7 | 54.7 | 24.5 |

| CD | 12.8 | 48.0 | 44.2 | 11.0 | 10.1 | 43.6 | 38.3 | 8.4 |

| EAT | 3.7 | 15.0 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 8.7 | 23.3 | 13.0 | 8.2 |

SOPH=social phobia; SAD=separation anxiety disorder; AGOR=agoraphobia; PANIC=panic disorder; GAD=general anxiety disorder; SIPH=simple phobia; OCD=obsessive/compulsive disorder; MDD=depression; MAN=mania/manic depression; ADHD= attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder; CD=conduct disorder; EAT=eating disorder.

For each PSC, its association with AUD is summarized in Table 2 by gender and gender interaction (i.e., male-to-female ratio). Adjusted for age and race/ethnicity, the odds ratio of having any AUD was significantly greater than 1 for each PSC (positive versus negative screen) in each gender group. However, there were significant gender interactions for GAD, ADHD, and ODD, such that the odds ratios were significantly smaller among males than females. The odds ratio of having alcohol dependence was significantly greater than 1 for each PSC in each gender group, and there were no significant gender interactions. Among males, the odds ratio of having alcohol abuse was not significantly different from 1 for SOPH, AGOR, GAD, SIPH, and EAT, and significantly greater than 1 for all other PSCs. Among females, the odds ratio of having alcohol abuse was not significantly different from 1 for SOPH, SAD, AGOR, and EAT, but significantly greater than 1 for all other PSCs. There were two significant gender interactions such that the odds ratios were higher for SAD and lower for GAD among males than females.

Table 2.

Odds ratio [95% CI] of adolescents ages 12–17 with a specific psychiatric symptom cluster (PSC) to have a DSM-IV alcohol use disorder, adjusted for age and race/ethnicity, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 2000

| PSCa | Base Category: No AUD Diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AUD | Alcohol Dependence | Alcohol Abuse | |||||||

| Male | Female | Male to Female Ratio | Male | Female | Male to Female Ratio | Male | Female | Male to Female Ratio | |

| SOPH | 1.45* [1.09, 1.93] | 1.51** [1.17, 1.95] | 0.96 [0.65, 1.42] | 1.66* [1.07, 2.58] | 1.92** [1.29, 2.86] | 0.86 [0.47, 1.57] | 1.34 [0.94, 1.90] | 1.30 [0.93, 1.80] | 1.03 [0.63, 1.70] |

| SAD | 2.79** [1.81, 4.31] | 1.66** [1.18, 2.35] | 1.68 [0.97, 2.89] | 3.80** [2.08, 6.94] | 3.19** [2.05, 4.96] | 1.19 [0.57, 2.51] | 2.30** [1.32, 3.99] | 0.93 [0.54, 1.60] | 2.47* [1.14, 5.36] |

| AGOR | 1.85** [1.20, 2.84] | 1.76** [1.31, 2.36] | 1.05 [0.62, 1.78] | 3.04** [1.76, 5.24] | 2.59** [1.75, 3.84] | 1.17 [0.60, 2.31] | 1.26 [0.65, 2.43] | 1.34 [0.92, 1.97] | 0.94 [0.44, 2.00] |

| PANIC | 3.03** [1.96, 4.70] | 3.32** [2.52, 4.38] | 0.91 [0.54, 1.55] | 4.93** [2.81, 8.65] | 5.18** [3.47, 7.71] | 0.95 [0.48, 1.89] | 2.11* [1.12, 3.97] | 2.42** [1.71, 3.43] | 0.87 [0.42, 1.82] |

| GAD | 1.56** [1.16, 2.10] | 2.92** [2.32, 3.67] | 0.53** [0.37, 0.78] | 2.44** [1.63, 3.65] | 3.83** [2.65, 5.54] | 0.64 [0.37, 1.10] | 1.14 [0.77, 1.70] | 2.48** [1.87, 3.29] | 0.46** [0.28, 0.76] |

| SIPH | 1.67** [1.13, 2.45] | 1.91** [1.50, 2.45] | 0.87 [0.55, 1.37] | 2.68** [1.60, 4.48] | 2.67** [1.80, 3.97] | 1.00 [0.52, 1.92] | 1.17 [0.68, 2.02] | 1.54** [1.13, 2.10] | 0.76 [0.41, 1.42] |

| OCD | 2.18** [1.63, 2.90] | 3.05** [2.36, 3.93] | 0.72 [0.48, 1.06] | 2.68** [1.78, 4.06] | 4.53** [3.11, 6.61] | 0.59 [0.34, 1.04] | 1.92** [1.33, 2.79] | 2.37** [1.74, 3.21] | 0.81 [0.50, 1.32] |

| MDD | 3.39** [2.54, 4.53] | 3.83** [3.04, 4.83] | 0.88 [0.61, 1.29] | 6.02** [4.05, 8.94] | 6.21** [4.24, 9.08] | 0.97 [0.56, 1.69] | 2.24** [1.51, 3.34] | 2.86** [2.16, 3.78] | 0.79 [0.48, 1.29] |

| MAN | 3.14** [1.96, 5.01] | 2.72** [1.80, 4.10] | 1.15 [0.62, 2.13] | 3.60** [1.92, 6.75] | 4.38** [2.50, 7.68] | 0.82 [0.35, 1.91] | 2.89** [1.58, 5.27] | 1.84* [1.06, 3.19] | 1.57 [0.70, 3.53] |

| ADHD | 2.15** [1.65, 2.80] | 3.33** [2.60, 4.26] | 0.65* [0.45, 0.93] | 2.92** [1.94, 4.38] | 4.47** [3.02, 6.61] | 0.65 [0.37, 1.14] | 1.78** [1.29, 2.46] | 2.77** [2.06, 3.72] | 0.64 [0.41, 1.01] |

| ODD | 3.09** [2.45, 3.90] | 4.49** [3.55, 5.67] | 0.69* [0.50, 0.95] | 3.60** [2.48, 5.21] | 5.44** [3.60, 8.24] | 0.66 [0.38, 1.15] | 2.85** [2.17, 3.75] | 4.02** [3.07, 5.27] | 0.71 [0.49, 1.02] |

| CD | 6.61** [5.26, 8.30] | 7.31** [5.74, 9.30] | 0.90 [0.64, 1.27] | 7.34** [5.08, 10.60] | 8.30** [5.60, 12.30] | 0.88 [0.51, 1.52] | 6.24** [4.76, 8.18] | 6.78** [5.12, 8.99] | 0.92 [0.62, 1.37] |

| EAT | 2.65** [1.69, 4.15] | 2.05** [1.49, 2.82] | 1.29 [0.75, 2.24] | 5.18** [2.96, 9.08] | 3.08** [1.93, 4.91] | 1.68 [0.82, 3.44] | 1.41 [0.72, 2.76] | 1.52 [0.98, 2.35] | 0.93 [0.41, 2.09] |

SOPH=social phobia; SAD=separation anxiety disorder; AGOR=agoraphobia; PANIC=panic disorder; GAD=general anxiety disorder; SIPH=simple phobia; OCD=obsessive/compulsive disorder; MDD=depression; MAN=mania/manic depression; ADHD=attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder; CD=conduct disorder; EAT=eating disorder.

p < .05

p < .01.

CI=confidence interval.

For each PSC, its association with AUD accounting for the presence or absence of other PSCs is summarized in Table 3 by gender and gender interaction (i.e., male-to-female ratio). With the profile of other PSCs being the same, males who had SAD, MDD, ODD, or CD had significantly increased odds for having any AUD, although the odds were significantly decreased for those who had GAD. By contrast, females who had PANIC, GAD, OCD, MDD, ODD, or CD had significantly increased odds for having any AUD. The odds ratio of having any AUD was significantly higher among males than females for those with SAD and significantly lower among males than females for those with GAD. With the profile of other PSCs being the same, males who had MDD, CD, or EAT and females who had PANIC, GAD, MDD, ODD, or CD had significantly increased odds for having alcohol dependence. Males who had SAD, ODD, or CD and females who had GAD, ODD, or CD had significantly increased odds for having alcohol abuse. Males who had GAD and females who had SAD had significantly decreased odds for having alcohol abuse. The odds ratio of having alcohol abuse was significantly higher among males than females for those with SAD and significantly lower among males than females for those with GAD.

Table 3.

Odds ratio [95% CI] of adolescents ages 12–17 with a specific psychiatric symptom cluster (PSC) to have a DSM-IV alcohol use disorder, adjusted for age and race/ethnicity as well as other PSCs (i.e., net of other PSCs), National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 2000

| PSCa | Base Category: No AUD Diagnosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AUD | Alcohol Dependence | Alcohol Abuse | |||||||

| Male | Female | Male to Female Ratio | Male | Female | Male to Female Ratio | Male | Female | Male to Female Ratio | |

| SOPH | 0.89 [0.64, 1.24] | 0.75 [0.55, 1.03] | 1.18 [0.74, 1.87] | 0.73 [0.42, 1.26] | 0.75 [0.45, 1.24] | 0.98 [0.46, 2.07] | 0.99 [0.68, 1.45] | 0.75 [0.52, 1.09] | 1.32 [0.76, 2.27] |

| SAD | 1.67* [1.03, 2.71] | 0.66 [0.43, 1.01] | 2.53** [1.36, 4.71] | 1.39 [0.60, 3.23] | 1.01 [0.58, 1.78] | 1.37 [0.50, 3.77] | 1.83* [1.09, 3.08] | 0.43** [0.23, 0.79] | 4.26** [1.94, 9.35] |

| AGOR | 0.86 [0.50, 1.49] | 0.89 [0.63, 1.27] | 0.97 [0.51, 1.85] | 1.03 [0.43, 2.47] | 0.98 [0.61, 1.56] | 1.06 [0.40, 2.84] | 0.75 [0.39, 1.43] | 0.83 [0.53, 1.30] | 0.90 [0.41, 1.99] |

| PANIC | 1.54 [0.88, 2.70] | 1.50* [1.05, 2.13] | 1.03 [0.51, 2.05] | 1.92 [0.80, 4.56] | 1.77* [1.09, 2.87] | 1.08 [0.40, 2.93] | 1.35 [0.69, 2.64] | 1.31 [0.85, 2.03] | 1.03 [0.45, 2.34] |

| GAD | 0.69* [0.49, 0.99] | 1.63** [1.23, 2.17] | 0.42** [0.27, 0.68] | 0.84 [0.49, 1.45] | 1.56* [1.01, 2.41] | 0.54 [0.27, 1.09] | 0.61* [0.40, 0.93] | 1.69** [1.20, 2.38] | 0.36** [0.21, 0.62] |

| SIPH | 0.78 [0.51, 1.18] | 0.89 [0.66, 1.20] | 0.87 [0.53, 1.45] | 0.94 [0.48, 1.87] | 0.95 [0.60, 1.50] | 0.99 [0.44, 2.23] | 0.66 [0.41, 1.08] | 0.85 [0.59, 1.22] | 0.78 [0.42, 1.45] |

| OCD | 1.24 [0.87, 1.75] | 1.44* [1.00, 2.06] | 0.86 [0.51, 1.43] | 1.06 [0.58, 1.94] | 1.59 [0.91, 2.76] | 0.67 [0.29, 1.54] | 1.35 [0.91, 2.01] | 1.36 [0.91, 2.03] | 0.99 [0.57, 1.75] |

| MDD | 1.80** [1.23, 2.62] | 1.54** [1.14, 2.07] | 1.17 [0.72, 1.90] | 2.99** [1.69, 5.27] | 2.11** [1.29, 3.43] | 1.42 [0.67, 3.00] | 1.24 [0.77, 1.99] | 1.29 [0.90, 1.84] | 0.96 [0.53, 1.76] |

| MAN | 0.89 [0.49, 1.59] | 0.79 [0.50, 1.25] | 1.12 [0.53, 2.36] | 0.55 [0.22, 1.35] | 0.98 [0.54, 1.78] | 0.56 [0.19, 1.65] | 1.22 [0.63, 2.34] | 0.64 [0.34, 1.19] | 1.91 [0.78, 4.69] |

| ADHD | 1.02 [0.73, 1.42] | 1.34 [0.96, 1.88] | 0.76 [0.47, 1.23] | 1.10 [0.66, 1.83] | 1.27 [0.77, 2.08] | 0.87 [0.43, 1.76] | 0.98 [0.66, 1.45] | 1.39 [0.92, 2.09] | 0.71 [0.40, 1.24] |

| ODD | 1.55** [1.14, 2.10] | 2.16** [1.65, 2.82] | 0.72 [0.49, 1.05] | 1.46 [0.93, 2.31] | 2.08** [1.32, 3.28] | 0.70 [0.37, 1.32] | 1.59* [1.11, 2.29] | 2.22** [1.62, 3.06] | 0.72 [0.46, 1.12] |

| CD | 4.93** [3.71, 6.55] | 4.09** [3.14, 5.33] | 1.21 [0.82, 1.78] | 4.78** [3.01, 7.58] | 3.83** [2.52, 5.80] | 1.25 [0.67, 2.32] | 5.02** [3.60, 7.00] | 4.30** [3.15, 5.87] | 1.17 [0.74, 1.84] |

| EAT | 1.33 [0.82, 2.16] | 1.04 [0.72, 1.49] | 1.28 [0.71, 2.32] | 2.34* [1.19, 4.60] | 1.38 [0.83, 2.29] | 1.70 [0.74, 3.92] | 0.76 [0.40, 1.45] | 0.83 [0.51, 1.36] | 0.91 [0.41, 2.04] |

SOPH=social phobia; SAD=separation anxiety disorder; AGOR=agoraphobia; PANIC=panic disorder; GAD=general anxiety disorder; SIPH=simple phobia; OCD= obsessive/compulsive disorder; MDD=depression; MAN=mania/manic depression; ADHD=attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder; CD=conduct disorder; EAT= eating disorder.

p < .05

p < .01.

CI=confidence interval.

The tetrachoric correlation matrix by gender is shown in Table 4. There are moderate to high correlations for anxiety symptoms (AGOR, PANIC, GAD, SIPH, and OCD), mood symptoms (MDD and MAN), and behavioral symptoms (ODD and CD). The correlation patterns are similar for both genders. Geomin factor loadings for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) for 1–3 factor solutions are shown in Table 5. The three-factor solution, which was similar for both genders, significantly improved the chi-square (DIFFTEST) and other fit criteria.

Table 4.

Correlationa matrix of psychiatric symptom clusters (PSC) by gender among adolescents ages 12–17, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 2000

| PSCb | SOPH | SAD | AGOR | PANIC | GAD | SIPH | OCD | MDD | MAN | ADHD | ODD | CD | EAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOPH | 1.00 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.20 |

| SAD | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| AGOR | 0.48 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| PANIC | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.33 |

| GAD | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.37 |

| SIPH | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.26 |

| OCD | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.34 |

| MDD | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.39 |

| MAN | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.31 |

| ADHD | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.31 |

| ODD | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.61 | 0.31 |

| CD | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.31 |

| EAT | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 1.00 |

Correlations are presented below and above the main diagonal for males and females, respectively.

SOPH=social phobia; SAD=separation anxiety disorder; AGOR=agoraphobia; PANIC=panic disorder; GAD=general anxiety disorder; SIPH=simple phobia; OCD= obsessive/compulsive disorder; MDD=depression; MAN=mania/manic depression; ADHD=attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder; CD=conduct disorder; EAT= eating disorder.

Table 5.

Geomin factor loadings for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) by gender among adolescents ages 12–17, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 2000

| PSCa | Male | Female | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 factorb | 2 factorsc | 3 factorsd | 1 factore | 2 factorsf | 3 factorsg | |||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| SOPH | 0.58* | 0.54* | 0.13* | 0.21* | 0.48* | −0.04 | 0.56* | 0.33* | 0.31* | 0.25* | 0.41* | −0.05 |

| SAD | 0.73* | 0.78* | 0.00 | 0.55* | 0.32* | −0.01 | 0.69* | 0.55* | 0.26* | 0.50* | 0.32* | −0.02 |

| AGOR | 0.74* | 0.90* | −0.15* | 0.90* | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.67* | 0.85* | 0.00 | 0.84* | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| PANIC | 0.72* | 0.68* | 0.13* | 0.33* | 0.51* | −0.02 | 0.71* | 0.26* | 0.53* | 0.14* | 0.66* | −0.07 |

| GAD | 0.67* | 0.51* | 0.28* | 0.16* | 0.56* | 0.07 | 0.68* | 0.17* | 0.57* | −0.02 | 0.78* | −0.13* |

| SIPH | 0.69* | 0.77* | −0.05 | 0.79* | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.64* | 0.58* | 0.18* | 0.73* | 0.00 | 0.20* |

| OCD | 0.72* | 0.62* | 0.21* | 0.23* | 0.59* | −0.01 | 0.75* | 0.34* | 0.50* | 0.33* | 0.48* | 0.07 |

| MDD | 0.76* | 0.45* | 0.47* | −0.01 | 0.74* | 0.17* | 0.77* | 0.00 | 0.79* | −0.15* | 0.92* | 0.00 |

| MAN | 0.71* | 0.36* | 0.52* | −0.02 | 0.66* | 0.24* | 0.69* | 0.05 | 0.67* | 0.03 | 0.64* | 0.10 |

| ADHD | 0.71* | 0.46* | 0.40* | 0.07 | 0.65* | 0.14* | 0.75* | 0.18* | 0.64* | 0.18* | 0.59* | 0.12* |

| ODD | 0.61* | 0.00 | 0.83* | 0.00 | 0.39* | 0.59* | 0.63* | −0.27* | 0.88* | −0.02 | 0.46* | 0.54* |

| CD | 0.51* | −0.04 | 0.70* | 0.21* | 0.00 | 0.82* | 0.54* | −0.33* | 0.82* | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.59* |

| EAT | 0.55* | 0.42* | 0.23* | 0.17* | 0.41* | 0.10 | 0.46* | 0.02 | 0.46* | 0.02 | 0.42* | 0.09 |

Significant at the .05 level.

SOPH=social phobia; SAD=separation anxiety disorder; AGOR=agoraphobia; PANIC=panic disorder; GAD=general anxiety disorder; SIPH=simple phobia; OCD=obsessive/compulsive disorder; MDD=depression; MAN=mania/manic depression; ADHD=attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder; CD=conduct disorder; EAT=eating disorder.

Chi-square=1122.2, df=65; CFI=0.901; TLI=0.881; RMSEA=0.041.

Chi-square=237.8, df=53; CFI=0.983; TLI=0.975; RMSEA=0.019.

Chi-square= 72.2, df=42; CFI=0.997; TLI=0.995; RMSEA=0.009; DIFFTEST (3F vs 2F) = 153.7 (11), p < .001.

Chi-square=1045.7, df=65; CFI=0.951; TLI=0.941; RMSEA=0.040.

Chi-square=312.5, df=53; CFI=0.987; TLI=0.981; RMSEA=0.023.

Chi-square=114.2, df=42; CFI=0.996; TLI=0.993; RMSEA=0.013; DIFFTEST (3F vs 2F) = 178.6 (11), p < .001.

Given the gender differences in the prevalence of PSCs and DSM-IV AUD, the ESEM model including age and race/ethnicity as covariates is conducted in the multiple group analysis framework presented in Table 6. The CFI and RMSEA indices indicated a generally good fit for the multiple gender group analysis (CFI = .983; TLI = .980; RMSEA = .011). The test for measurement invariance of intercepts (thresholds) and factor loadings indicated that metric/scalar measurement invariance did not hold (metric/scalar [chi-square=1003.892, df=488; CFI=0.986; TLI=0.986; RMSEA=0.010] against configural invariance [chi-square=929.247, df=452; CFI=0.989; TLI=0.986; RMSEA=0.010]: p<0.0001 for chi-square=111.965, df=36), so the standardized coefficients are shown for each gender group. Nevertheless, the coefficients were similar for both genders in the measurement model. PSC factor 1 (internalizing fear) was well defined by SAD, AGOR, and SIPH. PSC factor 2 (internalizing anxious–misery) was well defined by PANIC, GAD, OCD, MDD, MAN, ADHD, and ODD. PSC factor 3 (externalizing) was well defined by CD and ODD. There were cross-loadings for ODD on PSC factors 2 and 3 in the measurement model for both genders and for SOPH and OCD on PSC factors 1 and 2 for females. PSC factors were highly correlated for factors 1 and 2 and, among females, factors 2 and 3 and factors 1 and 2. With the same race/ethnicity, younger adolescents were more likely to have higher levels of PSC factor 1; older female adolescents were more likely to have higher levels of PSC factors 2 and 3. In the same age groups, both genders of Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks were more likely to have higher levels of PSC factor 1 compared with non-Hispanic Whites. For males, non-Hispanic Asians were more likely to have higher levels of PSC factor 1, and for females, non-Hispanic Native Americans were more likely to have higher levels of PSC factor 3, compared with non-Hispanic Whites.

Table 6.

Standardized coefficients [95% CI] from multiple-group exploratory structural equation modela of psychiatric symptom clusters (PSCs) and DSM-IV AUD criteria with covariates of age and race/ethnicity among adolescents ages 12–17, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse 2000

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC Factor 1 (internalizing fear) | PSC Factor 2 (internalizing anxious–misery) | PSC Factor 3 (externalizing) | PSC Factor 1 (internalizing fear) | PSC Factor 2 (internalizing anxious–misery) | PSC Factor 3 (externalizing) | |

| Measurement Part | ||||||

| PSC Factor 1 | ||||||

| PSC Factor 2 | 0.61** [0.28, 0.94] | 0.67** [0.60, 0.73] | ||||

| PSC Factor 3 | 0.12 [−0.71, 0.96] | 0.29 [−0.07, 0.64] | 0.28** [0.18, 0.39] | 0.57** [0.49, 0.66] | ||

| PSCb | ||||||

| SOPH | 0.28 [−0.23, 0.79] | 0.42* [0.08, 0.76] | −0.09 [−0.20, 0.03] | 0.35** [0.28, 0.42] | 0.34** [0.25, 0.43] | −0.09* [−0.18, −0.01] |

| SAD | 0.68** [0.44, 0.92] | 0.19 [−0.04, 0.43] | 0.00 [−0.05, 0.05] | 0.69** [0.61, 0.77] | 0.14* [0.03, 0.25] | −0.02 [−0.06, 0.03] |

| AGOR | 0.89** [0.83, 0.95] | −0.03 [−0.14, 0.08] | 0.00 [−0.07, 0.07] | 0.79** [0.73, 0.85] | 0.01 [−0.06, 0.08] | 0.00 [−0.06, 0.08] |

| PANIC | 0.40 [−0.03, 0.82] | 0.44* [0.09, 0.78] | 0.02 [−0.07, 0.11] | 0.20** [0.12, 0.28] | 0.60** [0.51, 0.68] | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.04] |

| GAD | 0.16 [−0.43, 0.75] | 0.60** [0.20, 1.01] | −0.03 [−0.17, 0.11] | −0.01 [−0.02, 0.01] | 0.86** [0.79, 0.94] | −0.19** [−0.28, −0.10] |

| SIPH | 0.77** [0.69, 0.84] | 0.02 [−0.12, 0.16] | 0.03 [−0.03, 0.10] | 0.67** [0.63, 0.72] | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.02] | 0.14** [0.05, 0.23] |

| OCD | 0.41 [−0.05, 0.87] | 0.44** [0.11, 0.78] | −0.03 [−0.13, 0.07] | 0.44** [0.37, 0.51] | 0.34** [0.26, 0.43] | 0.10* [0.01, 0.19] |

| MDD | −0.01 [−0.71, 0.68] | 0.80** [0.22, 1.38] | 0.14 [−0.06, 0.35] | −0.08 [−0.16, 0.01] | 0.88** [0.80, 0.95] | 0.00 [−0.03, 0.04] |

| MAN | 0.01 [−0.60, 0.61] | 0.69 [−0.08, 1.47] | 0.18 [−0.12, 0.48] | 0.10 [−0.00, 0.21] | 0.61** [0.49, 0.72] | 0.04 [−0.08, 0.15] |

| ADHD | 0.16 [−0.33, 0.66] | 0.60** [0.19, 1.00] | 0.09 [−0.06, 0.24] | 0.28** [0.21, 0.35] | 0.48** [0.39, 0.56] | 0.11** [0.03, 0.19] |

| ODD | −0.01 [−0.08, 0.06] | 0.46** [0.17, 0.75] | 0.45** [0.32, 0.58] | 0.01 [−0.02, 0.05] | 0.37** [0.27, 0.47] | 0.44** [0.35, 0.54] |

| CD | 0.19 [−0.59, 0.97] | 0.00 [−0.00, 0.00] | 0.94** [0.82, 1.05] | −0.01 [−0.08, 0.05] | 0.02 [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.93** [0.84, 1.01] |

| EAT | 0.25* [0.03, 0.47] | 0.33* [0.07, 0.59] | 0.16* [0.03, 0.29] | 0.00 [−0.08, 0.09] | 0.44** [0.34, 0.55] | 0.05 [−0.05, 0.15] |

| Structural Equation Part | ||||||

| Age (in years) | −0.23** [−0.27, −0.19] | −0.06 [−0.20, 0.09] | 0.14 [−0.06, 0.35] | −0.21** [−0.24, −0.17] | 0.08** [0.05, 0.12] | 0.07** [0.03, 0.11] |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref.=White) | ||||||

| Black | 0.57** [0.44, 0.71] | 0.00 [−0.46, 0.47] | −0.10 [−0.61, 0.42] | 0.50** [0.41, 0.59] | 0.03 [−0.06, 0.12] | 0.07 [−0.05, 0.19] |

| Native American | 0.10 [−2.51, 2.72] | −0.88 [−9.24, 7.48] | −0.01 [−1.10, 1.08] | 0.36 [−0.25, 0.98] | 0.06 [−0.30, 0.41] | 0.56** [0.22, 0.89] |

| Asian | 0.35** [0.12, 0.58] | 0.12 [−0.15, 0.39] | −0.17 [−0.58, 0.23] | 0.19 [−0.03, 0.42] | −0.14 [−0.32, 0.04] | 0.03 [−0.20, 0.26] |

| Hispanic | 0.39** [0.26, 0.52] | −0.08 [−0.45, 0.28] | −0.03 [−0.38, 0.33] | 0.28** [0.19, 0.37] | −0.05 [−0.14, 0.04] | 0.00 [−0.11, 0.12] |

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| AUD factor | AUD factor | |

| Measurement Part | ||

| AUD Criteria | ||

| Role obligation failure | 0.89** [0.87, 0.93] | 0.89** [0.86, 0.93] |

| Hazard use | 0.88** [0.85, 0.91] | 0.88** [0.85, 0.91] |

| Legal problems | 0.86** [0.82, 0.91] | 0.81** [0.75, 0.86] |

| Social problems | 0.88** [0.83, 0.92] | 0.87** [0.83, 0.91] |

| Tolerance | 0.87** [0.84, 0.90] | 0.80** [0.77, 0.84] |

| Withdrawal | 0.81** [0.77, 0.86] | 0.83** [0.77, 0.88] |

| Larger amounts | 0.64** [0.57, 0.70] | 0.76** [0.71, 0.82] |

| Cut down | 0.57** [0.46, 0.68] | 0.68** [0.59, 0.77] |

| Give up activities | 0.90** [0.87, 0.93] | 0.89** [0.86, 0.93] |

| Time spent | 0.91** [0.88, 0.93] | 0.90** [0.87, 0.93] |

| Psychological/physical problems | 0.93** [0.89, 0.96] | 0.85** [0.79, 0.92] |

| Structural Equation Part | ||

| PSC Factors | ||

| Factor 1 (internalizing fear) | 0.09 [−0.25, 0.44] | −0.12* [−0.23, −0.02] |

| Factor 2 (internalizing anxious–misery) | 0.09 [−0.05, 0.24] | 0.29** [0.16, 0.42] |

| Factor 3 (externalizing) | 0.43** [0.35, 0.52] | 0.42** [0.31, 0.52] |

| Age (in years) | 0.35** [0.31, 0.40] | 0.25** [0.20, 0.31] |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref.=White) | ||

| Black | −0.34** [−0.50, −0.18] | −0.33** [−0.48, −0.18] |

| Native American | −0.05 [−1.07, 0.96] | 0.52 [−2.43, 3.47] |

| Asian | −0.34** [−0.59, −0.09] | −0.46** [−0.76, −0.16] |

| Hispanic | −0.06 [−0.20, 0.08] | −0.01 [−0.14, 0.12] |

CFI=0.983, TLI=0.980, RMSEA=0.011. Test of measurement invariance between males and females (metric/scalar against configural): p<.0001.

SOPH=social phobia; SAD=separation anxiety disorder; AGOR=agoraphobia; PANIC=panic disorder; GAD=general anxiety disorder; SIPH=simple phobia; OCD=obsessive/compulsive disorder; MDD=depression; MAN=mania/manic depression; ADHD= attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder; CD=conduct disorder; EAT=eating disorder.

p < .05

p < .01.

CI=confidence interval.

The standardized factor loadings of the DSM-IV AUD criteria and structural estimates in each gender group also are included in Table 6. With all other variables being equal, both male and female adolescents who scored higher on the PSC factor 3 (externalizing) were more likely than those who scored lower to score higher on the latent AUD factor underlying the DSM-IV AUD criteria. Female adolescents who scored lower on the PSC factor 1 (fear) but scored higher on the PSC factor 2 (anxious–misery) tended to score higher on the latent AUD factor. For both genders, older adolescents were more likely to be on the higher levels of the latent AUD factor. Non-Hispanic Black and Asian adolescents were more likely to be on the lower levels of the latent AUD factor than their non-Hispanic White counterparts.

DISCUSSION

This study has examined associations between past-year PSCs and past-year DSM-IV AUDs in a representative sample of adolescents in the general population. The large sample size (n = 19,430, including 9,856 males and 9,574 females) permitted a more detailed examination of specific psychiatric symptoms within gender groups than is currently available in the literature. Our findings confirm associations between PSCs and DSM-IV AUDs, although the associations may vary by gender and type of AUDs. Notably, our study found that when adjusted for the presence of all other PSCs, age, and race/ethnicity, male and female adolescents with MDD, ODD or CD were more likely to have an AUD. The ODD/CD associations were generally similar for alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse, although not significant for alcohol dependence among males with ODD. In contrast, both male and female adolescents with depression symptoms were more likely to have alcohol dependence, but not abuse.

We found that the prevalence of specific PSCs differed by gender but the prevalence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence was basically the same across male and female adolescents. The absence of gender differences in DSM-IV AUDs has been reported in other national surveys (Harford et al., 2005; 2009; Swendsen, Burstein, Brady et al., 2002). Although Chen et al. (2005) found no significant gender by age interactions with SUD, gender differences may emerge in late adolescence when both male and female adolescents have gone through puberty, the timing of which has been linked to substance use (Cance, et al., 2013). This may explain the absence of gender difference among adolescents as females generally start puberty earlier than males.

It is interesting to note that in models unadjusted for the presence of other PSCs, each PSC was significantly related to each AUD, but only certain PSCs maintained a significant association with AUDs after adjusting for all other PSCs.. Some associations actually changed direction in the adjusted analysis. For example, the association between GAD and AUD in males changed from significantly positive to significantly negative. Results from a stepwise regression model (data not shown) revealed that, when other PSCs were entered into the model one at a time, GAD's initial unadjusted effect (OR=1.56, p=.003) kept decreasing and turned to significantly negative (OR=0.69, p=0.046 in the final, adjusted model). This indicates that the net (direct) effect of GAD was negative on AUD among males. The observed positive effect of GAD without adjusting by other PSCs was due to the confounding (indirect) effects of other co-morbid PSCs. We further decomposed the indirect effect, following the method proposed by Karlson and Holm (2011). The largest components of the indirect effect of GAD were from CD (36%), MDD (23%), OCD (22%), and SAD (14%)—the 4 PSCs that remained significantly positive in the final adjusted model. A possible explanation for the protective effect of GAD among males is that fear of physiological arousal as well as heightened worry about the consequences of alcohol use reduced the risk for alcohol dependence (Buckner et al., 2008). However, this was not the case for female adolescents, whose net effect of GAD remained significantly positive after adjusting for other PSCs. This may extend to the finding that the association between the internalizing anxious–misery factor and AUD was stronger in female than male adolescents (Dawson et al., 2010). Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms (e.g., different coping mechanisms or differences in psychiatric severity) underlying this gender difference. Some previous studies have found no concurrent associations between GAD and AUD after controlling for depression (Fröjd et al. 2011) or no direct effect of GAD on subsequent development of AUD after controlling for mood and other anxiety disorders (Zimmermann et al., 2003). Because these studies did not analyze males and females separately, it is possible that the opposite direct effects of GAD cancelled each other out.

We also observed some other gender differences in the associations between PSCs and DSM-IV AUDs. Male adolescents with SAD were more likely than those without SAD and females with SAD versus no SAD to have an AUD or alcohol abuse. These findings among adolescents are particularly noteworthy in comparison with a national study of adults by Goldstein, Dawson, Chou, et al. (2012) that found few significant gender differences when adjusted for co-occurring psychiatric disorders (e.g., higher odds ratio for females in the comorbid association between alcohol abuse and major depression). Although our study's inclusion of psychiatric symptom clusters rather than full diagnostic assessments limits specific comparisons, our findings are generally consistent with reports from a metropolitan area survey of 4,175 adolescents (Roberts et al. 2007b) that indicated significant associations between DSMIV mood and behavior psychiatric disorders and alcohol abuse and dependence. Although Roberts and colleagues (2007b) found a significant association between anxiety disorders and alcohol dependence, it was not significant when adjusted for the presence of other disorders.

Interpretation of the associations between PSCs and DSM-IV AUDs in our study is complicated by both conceptual and measurement issues (Gelhorn et al., 2008; Harford et al., 2010; Hasin and Paykin, 1998; 1999; Schuckit et al., 2008). DSM-IV excludes individuals who report one or two alcohol dependence criteria (i.e., diagnostic orphans), and these individuals actually are at a higher risk for subsequent AUDs compared with those without any dependence criteria (Harford et al. 2010). Because the DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol abuse may include diagnostic orphans who met one or two dependence criteria, comparisons between abuse and dependence are confounded. For example, Gelhorn and colleagues (2008) noted that DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol abuse may include some individuals who meet all four abuse criteria as well as two dependence criteria.

Studies further indicate that DSM-IV AUD criteria do not provide support for the distinction between alcohol abuse and dependence (Langenbucher et al., 2004; Martin et al., 1996) and that DSM-IV AUD criteria are indicators of a unidimensional latent trait (Gelhorn et al., 2007; Harford et al,. 2009; Kirisci et al., 2006; Saha et al., 2006). For these reasons, our study incorporated latent variable modeling of the DSM-IV AUD criteria and, in order to address the high comorbidity among symptom clusters according to differences in unadjusted and adjusted logistic models and the PSC correlation matrix, we also extended latent variable modeling to the PSCs.

The three-factor structure of PSC we identified in our study is generally consistent with that reported in the literature for adults (Krueger et al., 1998; Krueger and Markon, 2006) and adolescents in the NCS-A (Kessler et al., 2012). In both the NCS-A and our studies, SIPH and AGOR defined the fear factor, GAD and MDD defined the anxious–misery factor, and ODD and CD defined behavior (externalizing) disorders. There are, however, a few notable differences between our study and the NCS-A study. In our study, SAD was loaded more on the fear factor than on the anxious–misery factor, and PANIC was mainly loaded on the anxious–misery factor rather than on the fear factor. It is not the case in the NCS-A study. In the NCS-A study, ADHD and ODD were loaded on the behavior (externalizing) factor. In contrast, in our study, ADHD and ODD were loaded on the anxious–misery factor, although ODD also had high cross-loading with the externalizing factor. Explanations for the differences between our study and the NCS-A study might relate to differences in the number and content in the selection of PSCs. In our study, the inclusion of SAD in the fear factor may reflect adolescent reports concerning anticipatory fears related to parental separation, similar to other phobic reactions. Although ADHD included symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, our review of the symptom items and their distributions indicated that the ADHD cluster reflected more of attention deficit and not hyperactivity. Adolescents might interpret ADHD symptoms as similar to GAD and other anxiety symptoms. Farmer and colleagues (2009) reported a two-factor model of externalization defined by oppositional behavior disorder (ADHD and ODD) and social norm violation disorder (CD, ASPD, and SUDs). Therefore, the high ODD cross-loading with the anxiety–misery and externalizing factors in our study could indicate presence of subtypes (i.e., ODD/anxiety–misery and ODD/CD).

The lack of measurement invariance in the multiple group analysis suggests that the internalizing-externalizing PSCs factors may be slightly different constructs between male and female adolescents. As a result, it adds complications to meaningful interpretations of PSC measurements for gender comparisons. Despite these structural differences, the significant associations that we found between externalizing PSCs and AUDs among male and female adolescents in our study are consistent with other adult general-population surveys (Grant et al, 2004a; 2004b; Kessler et al., 1997; Kessler and Walters, 2002; Robins and Regier, 1991), providing further support for the developmentally stable associations of disruptive behaviors and AUD among both adolescents and adults in the general population. Though limited by the cross-sectional design of our study, the associations for disruptive behaviors (i.e., ODD and CD) and DSM-IV AUDs have been replicated in several prospective studies in diverse adolescent populations (Costello et al., 1999; 2003; Fergusson et al., 2005; Hayatbakhsh et al., 2008; Sung et al., 2004). Children with antisocial behaviors and related psychiatric disorders (i.e., ODD, CD) are more likely to experience alcohol problems during adolescence (Clark and Scheid, 2001; Clark et al., 2002; Gelhorn et al. 2007; Goldstein et al. 2006). Gelhorn and colleagues (2007) report that for adolescents, progressing from CD to ASPD is the norm, with 75% of CD related to ASPD. Goldstein and colleagues (2007) further note that the associations between CD and ASPD are stronger for childhood than for adolescent onset.

The gender differences found in our study for the associations between the internalizing PSC and AUD factors were unanticipated. Despite the overall gender similarity in the PSC and AUD measurement structure and the association between externalizing PSC and AUD factors, female but not male adolescents reported significant associations between the internalizing PSC and AUD factors. Similarly, in a national adult sample, Dawson, Goldstein, Moss, et al. (2010) found significantly stronger associations between alcohol dependence and internalizing disorders among females than males. The negative association between the fear factor and AUD factor among female adolescents in our study suggests a protective effect for AUD, which is supported by results from a recent UK national study. In the study, Edwards and colleagues (2014) found that childhood social phobia and separation anxiety were negatively associated with early adolescent alcohol use, though gender differences were absent. The authors hypothesize that internalizing fear may restrict peer interactions and exposure to alcohol. The evidence from literature in the area for social phobia, however, is inconclusive. For example, in a longitudinal study, Dahne and colleagues (2014) reported that elevated social phobia symptoms predicted higher odds of alcohol use.

In contrast to the protective effect of the fear factor, our findings indicate that the anxious-misery factor is a risk factor for AUD among female adolescents. Crum et al., (2008), however, found that a higher level of early depressed mood was associated with an earlier and increased risk of initiating alcohol use without parental permission for boys but not for girls. Our study, unfortunately, provides no information regarding the mechanism underlying these associations and therefore no explanations as to why they are present among female and not male adolescents. Future investigations of internalizing disorders and their associations with AUD are needed to provide explanations.

When interpreting our findings, several limitations need to be considered. First, the estimates of psychiatric disorders are based on screening items for DSM-III-R disorders rather than the actual DSM-IV diagnosis, and the items do not provide coverage for the full range of DSM-IV criteria. Second, the PSC estimates are nonhierarchical and may reflect effects of other illness or substance impairment. Third, the PSC estimates do not provide DSM-IV duration criteria or indications of marked impairment in areas of functioning. Fourth, the measurement is based on self-reports for the past 12 months. Finally, the cross-sectional study design does not assess the direction of associations and does not identify causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between PSCs and AUDs. PSCs and AUD may be initially unrelated but develop reciprocal influences with each other or they may reflect the presence of an unknown common antecedent factor.

Limitations notwithstanding, our study has provided confirmation for the association between psychiatric symptoms and DSM-IV AUD among adolescents in the general population. The inclusion of PSCs as brief screening scales may provide important information for studies in which the inclusion of more lengthy DSM-IV structured interviews is not feasible. Although the findings from the initial analysis of PSCs and DSM-IV AUD categorizations were generally comparable to those from the latent variable modeling of PSCs and AUD criteria, the latter analytic strategy enabled assessments of the underlying structure of the high rates of comorbidity associated with these symptom clusters.

In summary, the major findings from our study are as follows: (1) the factor structure of PSCs replicates that found in other general population studies of adolescents and adults and is comparable for gender; (2) the externalizing PSC factor for both gender groups is significantly related to the latent factor of DSM-IV AUD criteria; and (3) internalizing PSC factors for females are significantly related to AUD, with the fear factor providing a protective effect while the anxious-misery factor presenting as a risk factor for AUD. Future studies, in addition to verifying our findings with other national data, need to further examine the associations between internalizing dimensions and AUD among female adolescents. By clarifying the distinct contribution of each PSC to internalizing and externalizing dimensions of PSCs specifically related to AUD, brief screening tools may be developed to identify adolescents potentially at risk for alcohol use problems. Recognizing PSCs as risk factors for AUD will help draw attention to the importance of early identification and prevention, and facilitate appropriate treatment and referral.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by the Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System funded by NIAAA Contracts No.HHSN267200800023C and No. HHSN275201300016C to CSR, Incorporated. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the sponsoring agency or the Federal Government.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) 4th ed. APA; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Modeling. 2009;16:397–438. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo-Baum K, Höfler M, Gloster AT, Klotsche J, Lieb R, Beauducel A, Bühner M, Kessler RC, Wittchen HU. The structure of common mental disorders: a replication study in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18:204–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, et al. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cance JD, Ennett ST, Morgan-Lopez AA, Foshee VA, Talley AE. Perceived pubertal timing and recent substance use among adolescents: a longitudinal perspective. Addiction. 2013;108:1845–1854. doi: 10.1111/add.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Ya-F, Dennis ML, Funk RR. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Killeya-Jones LA, Vega WA. Prevalence and co-occurrence of psychiatric symptom clusters in the U.S. adolescent population using DISC predictive scales. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2005;1:22. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Scheid J. Comorbid mental disorders in adolescents with substance use disorders. In: Hubbard JR, Martin PR, editors. Substance Abuse in the Mentally and Physically Disabled. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2001. pp. 133–167. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Vanyukov M, Cornelius J. Childhood antisocial behavior and adolescent alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Chen H, Crawford TN, Brook JS, Gordon K. Personality disorders in early adolescence and the development of later substance use disorders in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effect of timing and sex. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:298–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Storr CL, Ialongo N, Anthony JC. Is depressed mood in childhood associated with an increased risk for initiation of alcohol use during early adolescence? Addict Behav. 2008;33:24–40. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahne J, Banducci AN, Kurdziel G, MacPherson L. Early adolescent symptoms of social phobia prospectively predict alcohol use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;79:926–936. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Moss HB, Li T-K, Grant BF. Gender differences in the relationship of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology to alcohol dependence. Likelihood, expression, and course. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins L, Harris WA, Lowry R, McManus T, Chyen D, Shanklin S, Lim C, Grunbaum JA, Wechsler H. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55:1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AC, Latendresse SJ, Heron J, Cho SB, Hickman M, Lewis G, Dick DM, Kendler KS. Childhood internalizing symptoms are negatively associated with early adolescent alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1680–1688. doi: 10.1111/acer.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Lewinsohn PM. Refinements in the hierarchical structure of externalizing psychiatric disorders: patterns of lifetime liability from mid-adolescence through early adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:699–710. doi: 10.1037/a0017205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:837–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröjd S, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M. Associations of Social Phobia and General Anxiety with Alcohol and Drug Use in A Community Sample of Adolescents. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:192–199. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelhorn H, Hartman C, Sakai J, Stallings M, Young S, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt J, Hopfer C, Crowley T. Toward DSM-V: an item response theory analysis of the diagnostic process for DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1329–1339. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318184ff2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelhorn HL, Sakai JT, Price RK, Crowley TJ. DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria as predictors of antisocial personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Grant BF, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Saha TD. Antisocial personality disorder with childhood- vs. adolescence-onset conduct disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:667–675. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000235762.82264.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Grant BF. Sex differences in prevalence and comorbidity of alcohol and drug use disorders: Results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:938–950. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004a;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004b;61:361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Grant BF, Yi H, Chen CM. Patterns of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria among adolescents and adults: results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:810–828. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164381.67723.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Yi H, Faden VB, Chen CM. The dimensionality of DSM-IV alcohol use disorders among adolescent and adult drinkers and symptom patterns by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:868–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Yi H, Grant BF. The five-year diagnostic utility of “Diagnostic Orphans” for alcohol use disorders in a national sample of young adults. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:410–417. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: Diagnostic “orphans” in a community sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Paykin A. Dependence symptoms but no diagnosis: Diagnostic “orphans” in a 1992 national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Jamrozik K, Al Mamun A, Bor W, Alati R. Adolescent problem behaviours predicting DSM-IV diagnoses of multiple substance use disorder: findings of a prospective birth cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:356–363. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlson KB, Holm A. Decomposing primary and secondary effects: A new decomposition method. Res Soc Stratif Mobil. 2011;29:221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Pine DS, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Merikangas KR. Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCA-A). Psychol Med. 2012;42:1997–2010. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Walters EE. The National Comorbidity Survey. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, editors. Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey: 2002. pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Martin C, Mezzich A, Brown S. Application of item response theory to quantify substance use disorder severity. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): a longitudinal-epidemiological study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: a model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher JW, Labouvie E, Martin CS, Sanjuan PM, Bavly L, Kirisci L, Chung T. An application of item response theory analysis to alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine criteria in DSM-IV. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:72–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, Bourdon K, Dulcan MK, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Lahey BB, Friman P. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): efficiently screening for diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Lüdtke O, Robitzsch A, Morin AJS, Tratwein U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: applications to students’ evaluations of university teaching. Struct Equ Modeling. 2009;16:439–476. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Langenbucher JW, Kaczynski NA, Chung T. Staging in the onset of DSM-IV alcohol symptoms in adolescents: survival/hazard analyses. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:549–558. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Version 7. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Rates of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among adolescents in a large metropolitan area. J Psychiatr Res. 2007a;41:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Comorbidity of substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents: evidence from an epidemiologic survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007b;88(Suppl 1):S4–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Regier DA. Psychiatric disorders in America: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Free Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Danko GP, Smith TL, Bierut LJ, Bucholz KK, Edenberg HJ, Hesselbrock V, Kramer J, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Trim R, Allen R, Kreikebaum S, Hinga B. The prognostic implications of DSM-IV abuse criteria in drinking adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, Davies M, Piacentini J, Schwab-Stone ME, Lahey BB, Bourdon K, Jensen PS, Bird HR, Canino G, Regier DA. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version 2 3 [DISC-2 3]: description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;3:865–877. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Household Survey on Drug Abuse—Methodology Reports and Questionnaires: 2000 Methodology Resource Book. SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sung M, Erkanli A, Angold A, Costello EJ. Effects of age at first substance use and psychiatric comorbidity in the development of substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J, Burstein M, Brady C, Conway KP, Dierker L, He J, Merikangas KR. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents. Results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:390–398. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WA, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel L. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: the NEMESIS study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Pfister H, Kessler RC, Lieb R. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: a 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1211–22. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]