Abstract

Objective

Diagnosis and intervention for infant hearing loss is often delayed in areas of healthcare disparity, such as rural Appalachia. Primary care providers play a key role in timely hearing healthcare. The purpose of this study was to assess the practice patterns of rural primary care providers (PCPs) regarding newborn hearing screening (NHS) and experiences with rural early hearing diagnosis and intervention (EHDI) programs in an area of known hearing healthcare disparity.

Study design

Cross sectional questionnaire study

Methods

Appalachian PCP’s in Kentucky were surveyed regarding practice patterns and experiences regarding the diagnosis and treatment of congenital hearing loss.

Results

93 Appalachian primary care practitioners responded and 85% reported that NHS is valuable for pediatric health. Family practitioners were less likely to receive infant NHS results than pediatricians (54.5% versus 95.2%, p < 0.01). A knowledge gap was identified in the goal ages for diagnosis and treatment of congenital hearing loss. Pediatrician providers were more likely to utilize diagnostic testing compared with family practice providers (p<0.001). Very rural practices (Beale code 7–9) were less likely to perform hearing evaluations in their practices compared with rural practices (Beale code 4–6) (p<0.001). Family practitioners reported less confidence than pediatricians in counseling and directing care of children who fail newborn hearing screening. 46% felt inadequately prepared or completely unprepared to manage children who fail the NHS.

Conclusions

Rural primary care providers face challenges in receiving communication regarding infant hearing screening and may lack confidence in directing and providing rural hearing healthcare for children.

Keywords: Health disparity, Congenital hearing loss, Rural healthcare

INTRODUCTION

Congenital hearing loss is a significant public health problem with major economic health care impact.1,2 Supported by the US Preventive Services Task Force,3 newborn hearing screening (NHS) has been widely implemented, and more than 92% of infants born in the US are now being screened at birth.4 This program has been established by the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (JCIH), which recommends screening by 1 month of age, definitive diagnostic testing completed by 3 months of age, and appropriate intervention by 6 months of age.5–8 Cochlear implantation is approved by the FDA for children as young as 12 months of age with severe hearing loss. Even though hearing loss is treatable in children it is a time sensitive disease. A delay in diagnosis and treatment of congenital hearing loss will result in life-long consequences in oral communication, which cannot be rectified later in life. NHS can effectively identify congenital hearing loss in a timely manner and expedite appropriate intervention to improve speech and oral language development.9–11

Even though pediatric hearing loss is treatable, unfortunately, there are still significant gaps and delays in hearing healthcare following failed newborn hearing screening, especially in rural communities.12 As many as half of the newborns who fail the screening test do not have an appropriate diagnosis by three months of age.13 The presence of disparities in diagnostic and intervention services result in some socioeconomic groups being at a high risk of becoming lost to follow-up.2 Patients in rural areas, such as Appalachia, face limited access to specialty care and may compound these concerns.14 Congenital hearing loss within the Appalachian region of Kentucky is common with an incidence of 1.28 per 1000 live births.12 Congenital hearing loss within the region is largely non-syndromic in nature; however, there have been no formal investigation of etiologies of hearing loss in Appalachian children. Children who are deaf or hard of hearing from Appalachia are alarmingly delayed in diagnosis and treatment of hearing loss.12,15 Appalachia is a 205,000 square mile region that spans 13 states and is home to more than 25 million people.16 This vast region largely faces extreme community health disparities. The 54 Appalachian counties in Kentucky are some of the most distressed regions of the entire Appalachian region. Because timing of pediatric hearing healthcare is the key in preventing long-term complications, it is vital to assess rural hearing healthcare practices. There is a paucity of literature investigating rural hearing healthcare, and further attention should be given to the topic, considering the access-to-care barriers that many rural residents experience.

Rural primary care providers (PCP) play a vital role in rural communities in coordinating and even providing of specialty health care. There is some indication, in general, that primary care providers lack of knowledge regarding newborn hearing screening and subsequent testing and treatment for infant hearing loss;17 however, no prior study has investigated hearing healthcare practice and experiences in the rural setting. The purpose of this study is to assess the pediatric hearing healthcare practice patterns and experiences of Appalachian primary care providers.

METHODS

The internal review boards of the University of Kentucky (protocol 11-0872-P3H) and the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services (protocol CHFS-IRB-CCSHCN-FY12-49) approved the study. Inclusion criteria included PCP in the Appalachian region of Kentucky who provide pediatric care and receive NHS reports from birthing hospitals. This region was selected for this investigation because of known pediatric hearing healthcare delays and disparities. This list of providers in the region was provided by the Kentucky Cabinet of Health and Family Services Commission for Children with Special Healthcare Needs. These providers, according to state EHDI data, have been sent newborn screening results between 2009 and 2012. A total of 595 potential participants providers were identified; however, valid and accurate mailing addresses could not be confirmed for all participants. Questionnaires were mailed to the 595 addresses. Providers were mailed a 25-item questionnaire assessing practice type and setting, percentage of practice devoted to pediatrics, knowledge of JCIH recommendations, confidence in addressing and counseling children with hearing loss, hearing healthcare services/exams provided in their practice, and interest in further training and education regarding congenital hearing loss. The questionnaire was based on previously utilized EHDI questionnaire.17 Question formats included fill in the blank, open-ended semi-structured questions, multiple choice, yes/no, and 4-point graded scale questions. Each mailing included an addressed stamped return envelope. Following mailing of the questionnaire, follow-up telephone calls were made to all the practices with working phone numbers to increase participation. A second copy of the questionnaire was faxed or mailed to the practices that were reached by telephone.

Based on the county of practice location, we determined rurality of the provider’s county using the US Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Continuum coding system.18 This system utilizes a 9-point scale of Beale codes where codes 1–3 were considered urban and 4–6 were considered rural, and 7–9 considered very rural.19 Returned questionnaires were analyzed by coding each item separately. Continuous variables were summarized by calculating means and categorical variables were described with counts and percentages. Multiple choice and graded-scale question answer frequencies were calculated. Data was managed using an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and statistical analysis was performed with Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Associations between measured variables were assessed using chi square tests for dichotomous variables and Kruskal-Wallis, students' two tailed t-test, and Mann Whitney U tests of significant difference and correlation.

RESULTS

595 potential participants were identified who practice primary care in Appalachia and have been recipients of newborn hearing screening results, encompassing 51 different counties in Kentucky. There are 124 pediatrician providers in Appalachian Kentucky and 43 participated in the study resulting in a 35% response rate from pediatricians. In total, 93 surveys were returned for an overall response rate of 15.6%. The actual number of general practice providers who care for children in Appalachia is unknown. Reported data included number of years in practice and experience with early childhood hearing loss (Table 1). Regarding rurality, 7 of the practices were in urban counties (Beale code 2), 31 were in rural counties (Beale codes 4–6), and 49 were in very rural counties (Beale code 7–9). Pediatrics-focused practices composed 57% of the urban practices, 58% of the rural practices, and only 34% of the very rural practices. Family practices represent 14% of urban practices, 22% of rural practices, and 51% of very rural practices. The percentage of NHS received for pediatric practices (95.2%) was significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of family medicine practices (54.5%). Pediatricians also reported seeing significant more children in general (p<0.001), as well as, children with hearing loss over the past three years when compared to other providers (p < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Data of Practice Types

| Pediatrics | Family Medicine |

Others Community Health Practices |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Responses | 43 | 34 | 16 |

| Counties Represented | 19 | 22 | 12 |

| Average Number of Years in Practice | 14.78 | 12.91 | 14.2 |

| Average Number of Children with Permanent Hearing Loss Seen in | |||

| Last 3 years | 3.84 | 1.79 | 2.6 |

| Percentage of Newborns in Practice that Provider Received Newborn | |||

| Hearing Screening Results | 95.19 | 54.58 | 54.21 |

| Percentage of Practice Devoted to Children Age 5 and Under | 58.7 | 20.76 | 35.06 |

| Training Background | |||

| MD | 35 (81%) | 13 (38%) | 7 |

| DO | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| PA | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| APRN | 2 | 11 (32%) | 0 |

| ARNP | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Did Not Report | 0 | 0 | 7 |

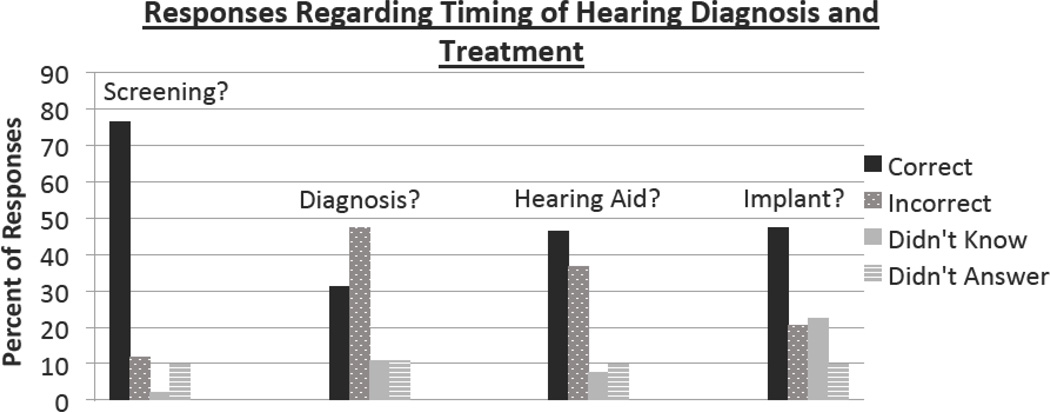

Providers were asked a series of questions regarding their knowledge of JCIH hearing testing and treatment standards using a fill in the blank question (Figure 1).7 These recommendations dictate that infants hearing should be screened by 1 month of age, a definitive diagnosis made by 3 months of age, and initiation of early intervention for hearing loss by 6 months of age. Regarding the age range screening of infant hearing (0–4 weeks), 76% of participants correctly answered the question. For the age range of diagnosis (0–3 months), 31% correctly answered the question while 57% answered incorrectly or stated they did not know. Regarding the age range for initiation of hearing aids for children, 46% answered correctly and 44% answered incorrectly or didn’t know. Additionally, we inquired about the youngest age a child could receive a cochlear implant, and according to the FDA guidelines is 12 months of age. Approximately 47% answered the question correctly and 42% answered incorrectly or didn’t know. Approximately 10% of participants did not answer these 4 questions. There were no significant differences between correct versus incorrect responses for these questions between different practice types, types of training, or rural status of practice setting. No significant differences were seen regarding knowledge of JCIH recommendations between those with an MD/DO degree and the PA’s/NP’s (p = 0.48). Likewise, there were no significant differences between participants with different educational backgrounds (MD/DO v. PA/NP) in their responses regarding the JCIH milestones (p = 0.69).

Figure 1.

Provider Knowledge of Timing of Diagnostic and Treatment services. Percentage of correct, incorrect, unknown, and unanswered responses for survey questions regarding completion of screening (1 month of age), diagnostic milestone (3 months of age), hearing aid fitting milestone (6 months of age), and earliest age for cochlear implantation (12 months of age).

Provider attitudes regarding the value of NHS and their confidence in discussing and counseling families regarding the NHS results, hearing loss consequences, and subsequent steps was assessed. We also assessed their impression regarding their training regarding management of children who fail their NHS (Table 2). 85% of all participants reported that they felt NHS was very valuable for pediatric health. There was a small non-significant difference in the responses between pediatrician providers (91%) from the family practitioners (76%) (p=0.08). 25% of participants reported limited or no confidence in explaining the NHS process to parents and there was a significant difference between pediatrician (7%) and family practitioner (44%) responses (p<0.001). 23% of participants reported limited or no confidence in explaining the next steps for parents after a failed NHS and there was a significant difference between pediatrician (5%) and family practitioner (41%) responses (p<0.001). 18% of participants reported limited or no confidence in explaining the consequences of pediatric hearing loss and there was a significant difference between pediatrician (2%) and family practitioner (32%) responses (p<0.001). Regarding the adequacy of their medical training to manage children who fail the NHS, 46% felt inadequately prepared or completely unprepared. Similar to the other question responses, there was a significant difference between pediatrician (33%) and family practitioner (65%) responses (p=0.005).

TABLE 2.

Provider Confidence Toward NHS and Pediatric Hearing Loss Training

| Pediatrics | Family Medicine | Other Community Health Practices |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS is very valuable for pediatric health | 39 (91%) | 26 (76%) | 14 (88%) |

| NHS is only somewhat valuable for pediatric health | 4 (9%) | 7 (21%) | 1 (6%) |

| Limited/No confidence in explaining the NHS process to parents | 3 (7%) | 15 (44%) | 5 (31%) |

| Limited/No confidence in explaining the next steps after a failed NHS | 2 (5%) | 14 (41%) | 5 (31%) |

| Limited/No confidence in explaining the consequences of hearing loss | 1 (2%) | 11 (32%) | 4 (25%) |

| Reported inadequate training to manage children who fail NHS | 14 (33%) | 22 (65%) | 7 (44%) |

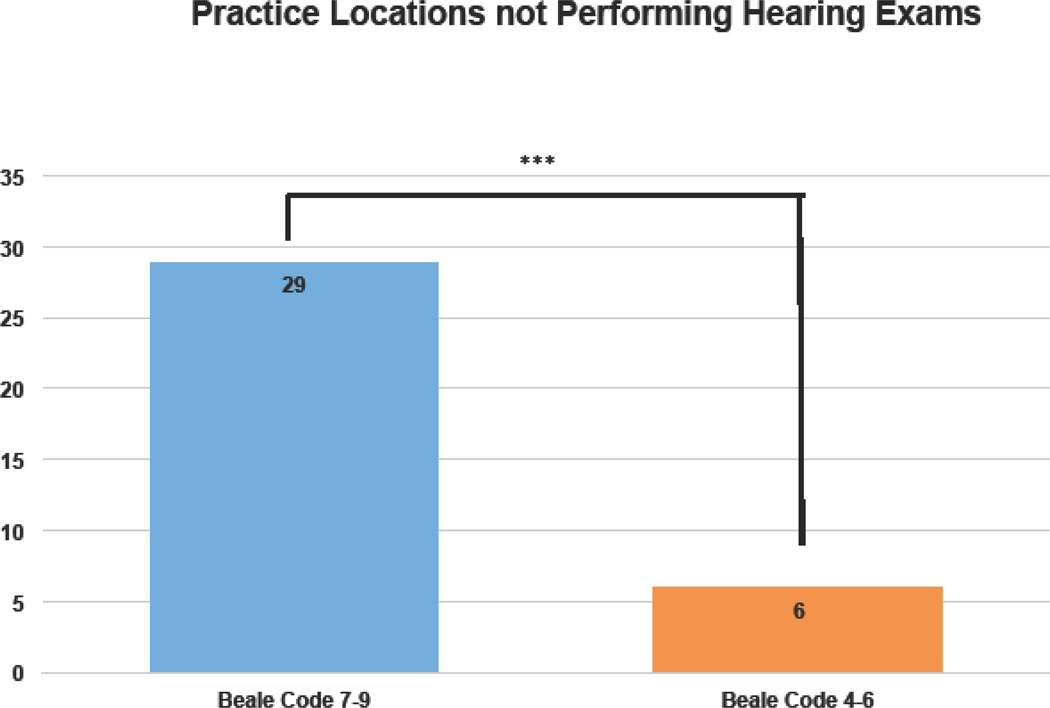

Regarding the practice of pediatric hearing healthcare, 56% of participants reported that perform some type of hearing examinations in their offices. The types of diagnostic testing directed by the providers is summarized in Table 3. Pediatrician providers were more likely to utilize diagnostic testing compared with family practice providers (p<0.001). Additionally, very rural practices (Beale code 7–9) were less likely to perform any type of hearing evaluation in their practices compared with rural practices (Beale code 4–6) (p<0.001) (Figure 2). Interest in further training opportunities through seminars and teleconferences on pediatric hearing loss with Continuing Medical Education (CME) credit was addressed. 60.0% of responders indicated that they would be interested, with an additional 26.7% citing they were "maybe" interested. The remaining 13.3% were not interested. These non-interested practitioners have been in practice for an average of 18.4 years as compared to the 13.3 years of all other practitioners. Interestingly, one of them responded that they were not confident in their knowledge of NHS.

TABLE 3.

Pediatric Hearing Diagnostic Resources Used in Practice

| Pediatrics | Family Medicine | Other Community Health Practices |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Auditory Brainstem Response | 23 (53%) | 4 (12%) | 4 (25%) |

| Tuning Fork | 5 (12%) | 15 (44%) | 7 (44%) |

| Tympanometry | 30 (70%) | 12 (35%) | 9 (56%) |

| Otoacoustic Emissions Test | 21 (49%) | 3 (9%) | 5 (31%) |

Figure 2.

Number of practices not providing In-Office Hearing Examinations. 60% (29 of 49) of very rural county (Beale code 7–9) practices do not provide hearing evaluations compared with 19% (6 of 31) of rural county (Beale codes 4–6) practices.

Free text comments provided by providers gave further insights into the practice of hearing healthcare in the Appalachian setting. Some of the comments addressing barrier in hearing healthcare included:

“Difficulty getting Medicaid to pay for more than 1 screen per year. Hard to follow up on abnormals secondary to inner ear fluid versus true hearing deficit when Medicaid involved.”

“Parent compliance is sometimes difficult to get them to go for BAER”

“Managed care pay only $7.00 for OAE test in my newborn nursery.”

Comments regarding the value of the newborn hearing screening process included:

“See so few failures, and then the repeats are normal. Not sure cost is justified. All childen I see that have significant hearing loss are from complications of illnesses.”

“It helps so much in my practice to know that a newborn has passed his or her NBS on his or her hearing, than to decide as we did before "can this pt hear". Thank you.”

Some participants expressed interest in specific training needs as it pertains to pediatric hearing health:

“We tried to use a OAE but it did not perform well. Better guidelines and product information would be helpful.”

“I would like to know more about ABR and how it is done”

“I need more training (educational) regarding hearing screen referrals and interpretation (in form of CME, teleconferences).”

DISCUSSION

Children who are deaf or hard of hearing in rural regions are at significant risk of being delayed in diagnosis and treatment.12,15,20 This is a multifactorial problem that must be managed on multiple levels. Management of congenital hearing loss requires a multidisciplinary approach can be complex, even when an abundance of specialists are present. The rural pediatric primary care provider plays a vital role in care provision, coordination and counseling regarding appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment in the setting of hearing loss. Because of the lack of specialists in some rural communities, PCP’s may face management of complex and sometimes involved health conditions. Further adding to the clinical strain and stress, rural providers face a higher patient load due to a workforce shortage in rural communities.21 The average providers in the Appalachian region of Kentucky care for 2,075 patients compared with the average Kentucky physician who cares for 1,784 patients and the national average of 1,226 patients for each PCP.22 Additionally, pediatric care in rural communities is less likely to be provided by pediatricians as it usually managed by family practitioners or non-physician providers. In the Appalachian region of Kentucky, there are approximately 279 family practice physicians, 54 PA’s, 322 NP’s while there are only 124 pediatricians.23 This highlights the importance of assessing the practice patterns of PCP’s in rural communities as it pertains to congenital hearing loss.

PCP’s within this rural region generally consider NHS to be valuable to infant health. Pediatricians are quite likely to report receipt of NHS results, unfortunately, general practices reported receiving this data only 54.5% of the time. This is concerning considering the predominance of general practices in the region. Non-pediatrician practices may proportionately see a fewer number of newborns and much of the targeted educational outreach concerning NHS has been directed towards pediatric practices and not other practice types.24,25 Lack of provider knowledge regarding key time point milestones for timely diagnosis and treatment of infant hearing loss is also concerning. Nearly 50% were not aware of the 3-month age of diagnosis milestone or the timing of cochlear implantation in congenital hearing loss. Certainly, if congenital hearing loss is encountered frequently in a given practice, then these milestones and standard practices may not be a priority. This aspect of limited practice knowledge may influence the finding of equivocal confidence in leading hearing healthcare in these providers. Lack of awareness of standard care guidelines and confidence in directing care may influence the delay in diagnosis and treatment observed in Appalachia. More rural practices were less likely to provide any type of hearing diagnostic testing through their offices. Hearing diagnostic equipment carries significant expense and current reimbursement may preclude rural clinician in providing these services. Rural providers may refer patients to centers with a full array of equipment; however, this may require significant travel time, which may affect compliance with testing. Shulman et al reported that the lack of service-system capacity, lack of provider knowledge, challenges to families in obtaining services, and information gaps prevent timely follow-up after infant hearing screening.24 Similar barriers have also been identified for delays in the fitting hearing aids by six months.26 Providers in this study expressed an interest in receiving further online training using resource that could include CME training modules, interactive learning community with specialists, and practice accountability.

A questionnaire study such as this is limited by a low response rate in spite of efforts to mitigate this issue with follow-up phone calls to providers. This is common among studies investigating physician’s attitudes and practices;17 however, 35% of the region’s pediatrician participated in the study, which is a greater response than other similar studies involving clinicians. The gap in our knowledge within this field is that other studies haven’t investigated practice patterns and perceptions within specific regions in which known pressing hearing health disparities exist. This study addresses that gap directly. The volume of the pediatric portion of the practices may also vary significantly and may affect the responses of the participants. It is quite possible that these results may underestimate the barriers encountered by providers within this area healthcare disparity. Considering the limited circulation of this questionnaire, the results cannot be generalized widely; however, it is the first of its kind to specifically investigate physician practices and experiences with NHS and infant hearing loss in a rural region with a known significant pediatric hearing health disparity. This study results need to be followed with further investigation of factors that influence the delivery of pediatric hearing health and the development of methods to address gaps in practice patterns.

CONCLUSIONS

Primary care providers play a key role in facilitating timely diagnostic and therapeutic care for children with hearing loss in rural regions, such as Appalachia. Lack of provider knowledge about NHS results and hearing loss is an important issue in this health disparity. Primary care providers may possess limited training and confidence to direct further diagnostic and therapeutic management of a child with hearing loss. Further training and multi-disciplinary support for clinicians may empower and equip these rural providers to better care for children who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Acknowledgments

SOURCE OF FUNDING

This publication was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (MLB, 8 KL2 TR000116-02) and the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (MLB, 1U24-DC012079-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Matthew L. Bush is a consultant for Med El Corporation.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST / DISCLOSURES

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. [Accessed March 27, 2011];Hearing loss. at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dd/ddhi.htm.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hearing Loss in Children. [Accessed August 26, 2013];Data and Statistics. at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/data.html.

- 3.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Universal screening for hearing loss in newborns: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics. 2008;122:143–148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaffney M, Green DR, Gaffney C. Newborn hearing screening and follow-up: Are children receiving recommended services? CDC Public Health Reports. 2010;125:199–207. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Supplement to the JCIH 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early intervention after confirmation that a child is deaf or hard of hearing. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1324–1349. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2000;106:798–817. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.798. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120:898–921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing 1994 position statement. Pediatrics. 1995;95:152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moeller MP. Early intervention and language development in children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):E43. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey AL, Coulter DK, Mehl AL. Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1161. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy CR, McCann DC, Campbell MJ, Law CM, Mullee M, Petrou S, Watkin P, Worsfold S, Yuen HM, Stevenson J. Language ability after early detection of permanent childhood hearing impairment. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:2131–2141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bush M, Bianchi K, Lester C, Shinn J, Gal T, Fardo D, Schoenberg N. Delays in Diagnosis of Congenital Hearing Loss in Rural Children. J Pediatr. 2014;164:393–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russ SA, Hanna D, DesGeorges J, Forsman I. Improving follow-up to newborn hearing screening: a learning-collaborative experience. Pediatrics. 2010;126:59–69. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0354K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Couto RA, Simpson NK, Harris G, editors. Sowing Seeds in the Mountains: Community Based Coalitions for Cancer Prevention and Control. Bethesda, MD: Appalachia Leadership Initiative on Cancer, DCPC, National Cancer Institute; 1994. (DHHS Pub. No. (NIH) 94-3779.) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bush M, Osetinsky M, Shinn J, Gal T, Fardo D, Schoenberg N. Assessment of Appalachian Region Pediatric Hearing Healthcare Disparities and Delays. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(7):1713–1717. doi: 10.1002/lary.24588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Appalachian Region. Appalachian Regional Commission. [Accessed January 16, 2015]; http://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/TheAppalachianRegion.asp.

- 17.Moeller MP, White KR, Shisler L. Primary care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to newborn hearing screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1357–1370. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.County Economic Status and Distressed Areas in Appalachia. [Accessed 4/18/13];Appalachian Regional Commission. http://www.arc.gov/appalachian_region/CountyEconomicStatusandDistressedAreasinAppalachia.asp.

- 19.Davis AF. Kentucky Annual Economic Report 2009. [Accessed 2/22/2013]. Kentucky’s Urban/Rural Landscape: What is driving the differences in wealth across Kentucky? http://cber.uky.edu/Downloads/annrpt09.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bush M, Burton M, Loan A, Shinn J. Timing Discrepancies of Early Intervention Hearing Services in Urban and Rural Cochlear Implant Recipients. Otology & Neurotology. 2013;34(9):1630–1635. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31829e83ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basco WT, Rimsza ME. Committee on Pediatric Workforce; American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrician workforce policy statement. Pediatrics. 2013 Aug;132(2):390–397. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casto JE. [Accessed 4/28/14];A Medical School for the Mountains: Training Doctors for Rural Care. http://www.arc.gov/magazine/articles.asp?ARTICLE_ID=48.

- 23.University of Kentucky Department of Family Medicine and Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Personal Communication. 2014. Apr 25, [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shulman S, Besculides, Saltzman A, Ireys H, White KR, Forsman I. Evaluation of the universal newborn hearing screening and intervention program. Pediatrics. 2010;126:19–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0354F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newborn Screening Authoring Committee. Newborn screening expands: Recommendations for pediatricians and medical homes - complications for the system. Pediatrics. 2008;121:192–217. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spivak L, Sokol H, Auerbach C, Gershkovick S. Newborn hearing screening follow-up: Factors affecting hearing aid fitting by 6 months of age. American Journal of Audiology. 2009;18:24–33. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/08-0015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]