Abstract

Purpose

to compare the baseline characteristics and chance of live birth in the different categories of poor responders identified by the combinations of the Bologna criteria and establish whether these groups comprise a homogenous population.

Methods

database containing clinical and laboratory information on IVF treatment cycles carried out at the Mother-Infant Department of the University Hospital of Modena between year 2007 and 2011 was analysed. This data was collected prospectively and recorded in the registered database of the fertility centre. Eight hundred and thirty women fulfilled the inclusion/ exclusion criteria of the study and 210 women fulfilled the Bologna criteria definition for poor ovarian response (POR). Five categories of poor responders were identified by different combinations of the Bologna criteria.

Results

There were no significant differences in female age, AFC, AMH, cycle cancellation rate and number of retrieved oocytes between the five groups. The live birth rate ranged between 5.5 and 7.4 % and was not statistically different in the five different categories of women defined as poor responders according to the Bologna criteria.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that the different groups of poor responders based on the Bologna criteria have similar IVF outcomes. This information validates the Bologna criteria definition as women having a uniform poor prognosis and also demonstrates that the Bologna criteria poor responders in the various subgroups represent a homogenous population with similar pre-clinical and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Poor response, Live birth rate, Bologna criteria, Ovarian reserve, AMH, AFC

Introduction

Poor ovarian response (POR) to gonadotropin stimulation leading to cycle cancellation and reduced chance of a live birth in an IVF programme still remains a challenge for infertility specialists. The starting point for any hypothetical strategy deployment is the correct identification of women and personalization of therapy with the aim of optimizing the outcome of every single IVF cycle and maximizing the live birth rate [1]. Inadequate ovarian response is the intrinsic inability of ovaries to respond appropriately to the stimulation chosen for the patient. This implies that, following exogenous gonadotropin stimulation, there is a lower number of growing follicles and lower serum estradiol levels (E2), resulting in a reduced number of retrieved oocytes and embryos available for transfer. The term “POR” is the most appropriate term for defining this condition [2].

The pathophysiological basis of POR, is to be mainly found in the ovarian reserve, which is dramatically reduced in these women. This means that in women that respond poorly to gonadotropins there is a low number of primordial follicles in the ovaries and a reduced number of recruitable follicles capable of growing following stimulation [3, 4]. Accordingly reduced age at menopause has been hypothesized for these women as a long-term consequence of having a smaller pool of primordial follicles [5]. In recent years, authors who have tried to define criteria for identifying POR have referred to variables such as: a peak E2 level of <300 pg/ml to <500 pg/ml [6, 7], requirement for an increased daily [8] or total gonadotropin stimulation dose [9] or previous cancelled cycle due to a poor response [10]. Although the number of developing follicles and/or the number of oocytes retrieved after a standard dose of ovarian stimulation are two of the most frequent criteria used, the suggested cut-offs have often varied [7, 11, 12]. Most clinicians prefer to choose the “less than 4 retrieved oocytes” criteria for predicting POR. The recruitment of fewer than 4 oocytes following a standard ovarian stimulation should be able to predict POR with a good sensitivity and specificity even in subsequent IVF cycles [12].

However, the lack of uniformity in diagnostic criteria has recently created the need for a consensus on the definition of POR [2]. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) consensus has established that to define a poor responder at least two of the following three features must be present: i) advanced female age ii) a previous POR iii) an abnormal ovarian reserve test (ORT) or in the absence of the above criteria two previous POR following maximal stimulation [2].

The presence of a reduced ovarian reserve is believed to be variably related to the deterioration of oocyte quality to the extent that it can alter embryo development and reduce the chances of a possible term pregnancy [13–17]. In clinical practice, when a woman is defined as poor responder on the sole basis of ovarian assessment, reproductive prognosis is not easy to determine. In the case of equal ovarian assessment, other parameters could influence pregnancy rate, for example age [18–21], which is the most important predictive variable of live birth in IVF. Globally, women who are poor responders have a lower pregnancy rate than normally responding women [19, 22–24]. Even in young poor responders IVF results are low but acceptable [25].

As seen with the Rotterdam criteria for PCOS [26], the Bologna criteria for poor response [2] would lead to the identification of different groups (or ‘phenotypes’) of poor responders. In particular five different classes of POR may be defined from the different combinations of the Bologna criteria as follows: i) one previous poor response and age ≥40 years, ii) one previous poor response and abnormal markers of ovarian reserve, iii) age ≥ 40 years and abnormal markers of ovarian reserve (the so-called expected poor response category), iv). one previous poor response in a woman aged ≥ 40 years and with abnormal markers of ovarian reserve, v) two previous POR cycles following maximal stimulation.

A complete dissertation about how the criteria were chosen is beyond the scope of this article and are reported in detail elsewhere [2]. Briefly the prevalence of poor response increases with age, and in women older than 40 years of age it is >50 % [2]. Hence age may was proposed as a post hoc test, which means that a woman aged over 40 years with one previous poor IVF cycle may be classified as a poor responder. Similarly in a woman with a poor response in first cycle, a reduced ovarian reserve must be confirmed using a post hoc test such as an abnormal ORT or a subsequent POR despite maximal stimulation [2].

Following the Bologna criteria definition it has been debated if the consensus actually defined a uniform group and the possibility that the various sub groups could have diverse baseline characteristics and varied clinical prognosis [27, 28]. Unless these apprehensions are tested and refuted the previously acknowledged difficulties in interpreting research on POR due to lack of a uniform definition will still continue to be a problem. To date, there is no data on the validation of the Bologna criteria and assessment of outcomes in the various categories of poor responders defined by the Bologna criteria which is essential to support its use by clinicians and researchers planning clinical studies. The aim of this study is to compare the baseline characteristics and the chances of live birth in the different categories of poor responders identified by the combinations of the Bologna criteria and establish whether these groups comprise a homogenous population.

Materials and methods

We analyzed the database containing clinical and laboratory information on IVF treatment cycles carried out at the Mother-Infant Department of the University Hospital of Modena between the years 2007 and 2011. These data were collected prospectively and recorded in the registered database of the fertility centre. Cycles were selected for analysis only when all the following inclusion criteria were satisfied:1. complete patient records on anamnestic, clinical, IVF cycle characteristics, and reproductive outcome after IVF, 2. starting gonadotrophin dose of at least 200 IU per day for the first 5 days of ovarian stimulation (in order to exclude women with low number of oocytes due to under stimulation of the ovaries), 3. oocyte retrieval performed by a senior doctor, 4. availability of at least one measurement between AMH and/ or AFC in the 3 months before commencing ovarian stimulation. All women had their ovarian reserve measured before entry in the IVF programme. The ovarian reserve evaluation consisted in the measurement of AMH and AFC. Clinical exclusion criteria were: previous ovarian surgery, presence of ovarian cysts, history of PID (pelvic inflammatory disease) or positivity to chlamydia antibody testing, any known endocrinological disease.

Women underwent IVF cycles according to the long GnRH agonist or the GnRH antagonist protocol. The long GnRH agonist protocol was based on the administration of daily leuprorelin (Enantone die, Takeda) or triptorelin (Decapeptyl 0.1 mg, Ipsen; Fertipeptil 0,1 mg, Ferring) starting from day 21 of the preceding menstrual cycle. Recombinant FSH (Gonal F, Merck Serono or Puregon, MSD) at a dose of at least 200 IU/day (range 200–300 IU/day) subcutaneously was commenced when pituitary desensitization was achieved (~14 days after the initiation of GnRH agonist), as evidenced by the absence of ovarian follicles > 10 mm and endometrial thickness <4 mm on transvaginal ultrasound examination. The GnRH antagonist protocol was based on the administration of recombinant FSH (Gonal F, Merck Serono or Puregon, MSD Organon) at a dose of at least 200 IU/day (range 200–300 IU/day) subcutaneously from day 2 of a spontaneous menstrual cycle. The GnRH antagonist, Ganirelix (Orgalutran, MSD) or Cetrorelix (Cetrotide, Merck Serono), was next administered daily by s.c. injection (0.25 mg/d) from the day of the stimulation cycle when the first follicle reached 14 mm in size to the day of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) administration. When follicles reached ≥18 mm, 10000 IU of hCG (Gonasi, IBSA) or recombinant hCG (Ovitrelle, Merck Serono) were administrated intramuscularly/ subcutaneously and 34–36 h later follicles were aspirated under patient sedation.

Clinical pregnancy was defined as from ultrasound visualization of a gestational sac with evidence of a fetal heartbeat, excluding all ectopic and biochemical pregnancies. As per clinical practice all pregnancies were followed up to delivery and the outcome recorded. Live birth was defined by the birth of at least one live-born child. All women gave written informed consent at the time of the IVF cycle for recording and for the use of laboratory and clinical data related to their medical history for clinical research purpose. Institutional review board (IRB) for the retrospective analyses was obtained.

Ovarian reserve markers assessment

As per clinical practice all women entering the IVF program in the clinic underwent ovarian reserve markers (AFC and/or AMH) measurement on a routine basis. All ultrasound examinations for AFC evaluation were carried out in the early- to mid- follicular phase by using the multifrequency vaginal probe on a GE Voluson E6 (GE, Milan, Italy). Examination of the ovary was established by scanning from the outer to the inner margin. All 2–10 mm follicles in site were counted in each ovary. Follicular size was measured by using the internal diameters of the area. The mean of two perpendicular measurements was assumed to be the follicular size. The sum of counts in both ovaries produced the AFC.

The blood sample for AMH determination was performed on the day in which women were addressed to IVF, independently of the last menstrual cycle. The blood was centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min and the serum was stored in polypropylene tubes at −20 °C. Serum AMH was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using the Beckman Coulter, Inc. (Chaska, MN, USA) AMH ELISA kit (Immunotech version, Marseilles, France). AMH values were presented in concentration of ng/ml (conversion factor to pmol/L = 7.143 ng/ml). The detection limit of the assay was 0.14 ng/ml; intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 12.3 and 14.2 %, respectively.

Statistical analysis

According to the Bologna Consensus [2] 2 out of 3 criteria need to be present to define a patient as poor responder: 1. maternal age ≥ 40 years, 2. AMH <1 ng/ml or AFC <7 follicles, 3. previous poor response, defined as a cycle previously cancelled because of absent ovarian response or if fewer than 4 oocytes were retrieved. Five different classes of POR may be defined from the different combinations of the Bologna criteria: i). a previous poor response and age ≥40 years, ii). previous poor response and abnormal markers of ovarian reserve, iii). age ≥40 years and abnormal markers of ovarian reserve, iv). previous poor response and age ≥40 and abnormal markers of ovarian reserve, V. two previous poor responses.

The outcome of IVF stimulated cycles and the rate of live birth in different categories were then compared. Continuous data were given as mean and SD. Groups of women were compared with student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage. Differences between proportions were evaluated with chi-square test. Missing data were excluded per test. Statistical significance was set for P < 0.05. GraphPad Prism version 6 (LaJolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

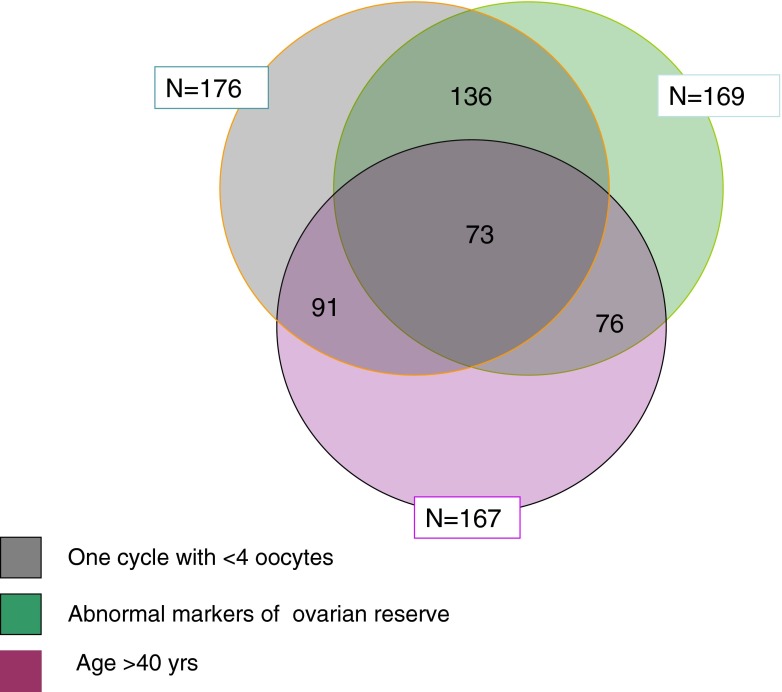

In our database, 830 women fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study and 210 women fulfilled the Bologna definition of poor response. Women’ characteristics were summarized in Table 1. Expectedly, poor responders were significantly older than normal responders while there were no differences for the percentage of smokers, diagnosis, type and cause of infertility. The live birth rate was 30.5 % in normal responders and 6.3 % in poor responders (Table 1). The five different combinations of the Bologna criteria leading to diagnosis of POR are reported in Table 2. A total of 167 women were > 40 years of age, 176 women had a retrieval of less than 4 oocytes in the index cycle and 91 of them were > 40 years. Of the 176 women with less than 4 oocytes, 106 had already had a previous cycle and in 76 of these an oocyte yield of <4 oocytes was reported. Out of 830 investigated women an abnormal ORT was found in 169 women and 136 of them had an oocyte yield < 4. Seventy-six women were expected poor responders, having had an abnormal ORT and age >40 years. Seventy-three women met all three Bologna criteria of poor response (Table 3 and Fig. 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients defined as normal or poor responders according to the Bologna criteria

| Variables | Normal responders | Poor responders |

|---|---|---|

| n | 620 | 210 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 36 (33–39) | 39 (35–40)* |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 21.8 (20–24) | 22.3 (20.8-25.1) |

| Smokers, % | 19.3 | 20.1 |

| Duration of infertility (months) | 29.2 ± 15.5 | 46.3 ± 20.5* |

| Type of infertility | ||

| Primary (%) | 75 | 78 |

| Secondary (%) | 25 | 22 |

| Causes of infertility (%) | ||

| Male factor | 47.6 | 48.5 |

| Tubal factor | 18.1 | 15.1 |

| Endometriosis | 13.5 | 12.1 |

| Unexplained | 21.8 | 24.3 |

| Clinical pregnancy rate (%) | 41.7 | 13.1* |

| Live birth rate (%) | 30.5 | 6.3* |

*p < 0.05

Table 2.

Different combination of Bologna criteria [2] leading to the diagnosis of POR

| Poor ovarian response categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4* | 5 |

| <4 oocytes retrieved | + +a | + | + | − | + |

| Age >40 | − | + | - | + | + |

| Abnormal marker of ovarian reserve | − | − | + | + | + |

atwo previous cycles with <4 oocytes retrieved are sufficient to diagnose poor response

*category including the so called “expected poor responders”

Table 3.

Outcome of IVF/ICSI cycles in different categories of women diagnosed as poor responders according to Bologna criteria

| Poor ovarian response categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Variables | Two cycles with <4oocytes | Age >40 + cycle with <4oocytes | Age > 40 + abnormal markers of ovarian reserve | Cycle with <4oocytes + abnormal markers of ovarian reserve | Cycle with <4oocytes + age > 40 + abnormal markers of ovarian reserve |

| Number of patients | 76 | 91 | 76 | 136 | 73 |

| Age (years) (mean, SD) | 39 ± 4.7 | 41.4 ± 1.1 | 41.3 ± 0.9 | 38 ± 3.9 | 41.8 ± 1.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2), (mean, SD) | 22.1 ± 2.2 | 22.3 ± 1.8 | 23.0 ± 2.3 | 21.9 ± 2.7 | 22.1 ± 2.4 |

| Smokers, % | 20.3 | 19.6 | 19.6 | 20.1 | 19.9 |

| Duration of infertility, months (mean,SD) | 45 ± 21 | 44 ± 22 | 47 ± 26 | 43 ± 24 | 46 ± 20 |

| AFC (n) (mean, SD) | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 0.87 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 3.9 ± 1.1 |

| AMH (ng/ml) (mean,SD) | 0.6 ± 0.29 | 0,5 ± 0,32 | 0,65 ± 0,29 | 0,5 ± 0,3 | 0,57 ± 0,31 |

| No. of oocytes (mean, SD) | 1.98 ± 1.1 | 1.93 ± 1.23 | 1.76 ± 1.02 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 1.1 |

| No. of embryos transferred (mean, SD) | 1.3 ± 0.15 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.13 | 1.2 ± 0.17 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Cycles with oocyte retrieval (%) | 79.5 | 75.6 | 71.1 | 81.1 | 70.1 |

| Cycles with embryo transfer (%) | 69.1 | 63.2 | 66.3 | 70.6 | 60.4 |

| Clinical pregnancy rate (per started cycle) (%) | 13.7 | 12.5 | 14.3 | 13.4 | 12.5 |

| Live birth rate (per started cycle) | 7.4 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 5.5 |

Fig. 1.

According to the Bologna Criteria for poor response, two out of three criteria need to be present in order to formulate the diagnosis of poor response. Of the 176 women with less than 4 oocytes, 91 were older than 40. An abnormal ORT was found in 169 women and 136 of them had an oocyte yield lower than 4. Seventy-six women were expected poor responders, having had an abnormal ORT and age >40. Seventy-three women met all three Bologna criteria of poor response

Table 3 shows data concerning the IVF ± ICSI reproductive outcomes of women divided into categories on the basis of a different combinations of the Bologna criteria. There was no significant difference among subgroups of women in the number of retrieved oocytes. The rate of women reaching the oocytes pick up and the embryo transfer was similar in different groups of women. Similarly, the clinical pregnancy rate and the live birth rate were not different among the groups. The rate of live birth ranged between 5.5 and 7.4 % in the five different categories of women.

Discussion

The proper identification of a poor responder in the preconceptional phase has value only if this allows correct evaluation of the prognosis. If a poor responder could be informed about the bad reproductive prognosis beforehand, they could perhaps deal with the IVF treatment with less expectation thereby reducing their physical and psychological stress [29]. According to the results of our study, the adoption of the Bologna criteria allows the identification of women with a reproductive chance lower than 8 % following IVF. This information is very useful for the clinician for adequate counselling.

Our results are in accordance with a recent retrospective study involving 485 women defined as poor responders according to the Bologna criteria reporting collectively a live birth of 6 % per cycle. [30]. For many years the identification of POR was only based on the history of a single IVF cycle with low oocyte yield, usually less than 4 [12, 31]. However, the ovarian response to a single treatment, even if important for the clinical outcome of the cycle, has a low predictive value for the outcome of future treatments. Previous studies in fact have demonstrated that in successive cycles women with one previous POR may have a normal response [32, 33]. In one study the occurrence of a POR in a second cycle was evident in only 62.4 % [32] of women with a first POR, implying that at least one-third of previous poor responders will have a normal response in subsequent cycles.

In a more recent retrospective study of 142 poor responders, only 46.5 % had a second poor response following ovarian stimulation and, most importantly, the rate of live birth was 34.3 and 13.6 % in those women with a normal response or with a repeated POR [33]. In the same study the age of women with a repeated poor response was significantly higher than that of women who showed a normal response in the second stimulation cycle [33].

These data confirm a complex interaction between reduced ovarian reserve, age, ovarian response to gonadotrophins and reproductive potential in women undergoing IVF. Undoubtedly the reduced prospects for pregnancy in women with few oocytes in IVF has to be attributed to the relevant effect of female age since poor responders are usually of higher age than controls (normal responders). The decline in oocyte quality with advancing female age occurs in parallel to the reduction in the number of ovarian follicles, hence explaining the detrimental effect of poor response on reproductive competence. A poor response, occurring in an aged women (i.e., older than 40) is with high probability due to reduced ovarian reserve and the combination of the two criteria permits to identify poor responder women with low possibility of success.

One of the Bologna criteria for the definition of POR is the presence of abnormal markers of ovarian reserve. AMH and AFC are now considered the most reliable and accurate markers of ovarian reserve [3, 34]. The two markers are strongly related to the quantitative aspect of ovarian reserve; hence a low AMH and/or AFC are highly indicative of possible low number of growing follicles and oocyte following ovarian stimulation. Moreover, both low AMH and AFC have been associated to reduced pregnancy and live birth following IVF independent of age [35–41]. This may indicate some relationship between quantity and quality of oocytes, with a detrimental effect on quality of oocytes derived by pathological early reduction in ovarian reserve. Accordingly, an increased rate of miscarriages following embryo transfer has been reported in women with low AMH or AFC [15, 42–44]. Women with a previous poor response to maximal gonadotrophin stimulation and abnormal ovarian reserve markers may be classified as women with reduced ovarian reserve and hence definite poor responders.

The present study because of its retrospective design has relevant limitations, including a biased selection of women recruited for the study. As the ESHRE consensus for defining POR did not specify one specific cut-off for AFC and AMH [2], the current study selected < 1 ng/ mL for AMH and < 7 for AFC as values to define reduced ovarian reserve may be criticised. Similarly, a possible source of bias may be due to the varied ovarian stimulation regimens with different types of pituitary suppression and different gonadotrophin doses. In particular the gonadotrophin starting dose for women included in the study ranged between 200 and 400 IU daily which was higher than 150 IU as previously proposed [2].

Conclusions

The Bologna criteria for POR, as confirmed in our study, are capable of identifying women with a poor reproductive prognosis based on the sum of various criteria (i.e., low number of eggs, advanced age and/or abnormal ovarian reserve markers). The Bologna criteria analysed individually are all independent factors predictive of reproductive success after IVF. The combined use of these features, increases the reliability of the identification of women with worse prognosis. Women with diagnosis of poor response according to the Bologna criteria have a chance of live birth < 8 %. This information allows the clinician to provide women with correct information regarding their reproductive prognosis, hence permitting to evaluate the risks and benefits and the cost-effectiveness of ART on an individual basis.

Footnotes

Capsule Bologna criteria identifiy subgroups of poor responders with a homogeneous and low reproductive prognosis.

References

- 1.La Marca A, Sunkara SK. Individualization of controlled ovarian stimulation in IVF using ovarian reserve markers: from theory to practice. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(1):124–40. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferraretti AP, La Marca A, Fauser BC, Tarlatzis B, Nargund G, Gianaroli L. ESHRE working group on POR definition. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1616–24. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Radi D, Argento C, Baraldi E, Artenisio AC, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technology (ART) Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(2):113–30. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Marca A, Grisendi V, Giulini S, Argento C, Tirelli A, Dondi G, et al. Individualization of the FSH starting dose in IVF/ICSI cycles using the antral follicle count. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.La Marca A, Dondi G, Sighinolfi G, Giulini S, Papaleo E, Cagnacci A, et al. The ovarian response to controlled stimulation in IVF cycles may be predictive of the age at menopause. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(11):2530–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia JE, Jones GS, Acosta AA, Wright G. HMG/hCGfollicularmaturation for oocytes aspiration: phase II, 1981. Fertil Steril. 1983;39:174–9. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46815-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raga F, Bonilla-Musoles F, Casan EM, Bonilla F. Recombinant follicle stimulating hormone stimulation in poor responders with normal basal concentrations of follicle stimulating hormone and oestradiol: improved reproductive outcome. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1431–4. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.6.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faber BM, Mayer J, Cox B, Jones D, Toner JP, Oehninger S, et al. Cessation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy combined with high-dose gonadotropin stimulation yields favorable pregnancy results in low responders. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:826–30. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaker A, Yates R, Flemming R, Coutts J, Jamieson M. Absence of effect of adjuvant growth hormone therapy on follicular responses to exogenous gonadotrophins in women: normal and poor responders. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:919–23. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manzi D, Thorton K, Scott L, Nulsen J. The value of increasing the dose of HMG in women who initially demonstrate a poor response. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:251–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56874-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarmolinskaya M, Land J, Dumoulin J, Evers J. High-dose human menopausal gonadotropin stimulation in poor responders does not improve in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:961–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bancsi LF, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Habbema JD, te Velde ER. Impact of repeated antral follicle counts on the prediction of POR in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazout A, Bouchard P, Seifer DB, Aussage P, Junca AM, Cohen-Bacrie P. Serum antimullerian hormone/mullerian- inhibiting substance appears to be a more discriminatory marker of assisted reproductive technology outcome than follicle-stimulating hormone, inhibin B, or estradiol. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebner T, Sommergruber M, Moser M, Shebl O, Schreier-Lechner E, Tews G. Basal level of anti-Mu¨llerian hormone is associated with oocyte quality in stimulated cycles. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2022–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lekamge DN, Barry M, Kolo M, Lane M, Gilchrist RB, Tremellen KP. Anti-Müllerian hormone as a predictor of IVF outcome. Reprod BioMed Online. 2007;14:602–10. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61053-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahu B, Oztutrk O, Serhal P, Jayaprakasan K. Do ORTs predict miscarriage in women undergoing assisted reproduction treatment? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153(2):181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Younis JS, Jadaon J, Izhaki I, Haddad S, Radin O, Bar-Ami S, et al. A simple multivariate score could predict ovarian reserve, as well as pregnancy rate, in infertile women. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karande V, Gleicher N. A rational approach to the management of low responders in IVF. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1744–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.7.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galey-Fontaine J, Cedrin-Durnerin I, Chaibi R, Massin N, Hugues JN. Age andovarian reserve are distinct predictive factors of cycle outcome in low responders. Reprod BioMed Online. 2005;10:94–9. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhen XM, Qiao J, Li R, Wang LN, Liu P. The clinical analysis of POR in in-vitro-fertilization embryo-transfer among Chinese couples. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25:17–22. doi: 10.1007/s10815-007-9187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Giulini S, Traglia M, Argento C, Sala C, et al. Normal serum concentrations of anti-Müllerian hormone in women with regular menstrual cycles. Reprod BioMed Online. 2010;21(4):463–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Timeva T, Milachich T, Antonova I, Arabaji T, Shterev A, Omar HA. Correlation between number of retrieved oocytes and pregnancy rate after in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm infection. Sci World J. 2006;6:686–90. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Gaast MH, Eijkemans MJ, van der Net JB, de Boer EJ, Burger CW, van Leeuwen FE, et al. Optimum number of oocytes for a successful first IVF treatment cycle. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;13:476–80. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendriks DJ, te Velde ER, Looman CW, Bancsi LF, Broekmans FJ. Expected poorovarian response in predicting cumulative pregnancy rates: a powerful tool. Reprod BioMed Online. 2008;17:727–36. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oudendijk JF, Yarde F, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, Broer SL. The poor responder in IVF: is the prognosis always poor?: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broekmans FJ, Knauff EA, Valkenburg O, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC. PCOS according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria: change in prevalence among WHO-II anovulation and association with metabolic factors. BJOG. 2006;113:1210–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papathanasiou A. Implementing the ESHRE ‘poor responder’ criteria in research studies: methodological implications. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(9):1835–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venetis CA. The Bologna criteria for POR: the good, the bad and the way forward. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(9):1839–41. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domar A, Gordon K, Garcia-Velasco J, La Marca A, Barriere P, Beligotti F. Understanding the perceptions of and emotional barriers to infertility treatment: a survey in four European countries. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(4):1073–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polyzos NP, Nwoye M, Corona R, Blockeel C, Stoop D, Haentjens P, et al. Live birth rates in Bologna poor responders treated with ovarian stimulation for IVF/ICSI. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;28(4):469–74. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarlatzis BC, Zepiridis L, Grimbizis G, Bontis J. Clinical management of low ovarian response to stimulation for IVF: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:61–76. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klinkert ER, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Te Velde ER. A poor response in the first in vitro fertilization cycle is not necessarily related to a poor prognosis in subsequent cycles. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(5):1247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moolenaar LM, Mohiuddin S, Munro Davie M, Merrilees MA, Broekmans FJ, Mol BW, et al. High live birth rate in the subsequent IVF cycle after first-cyclepoor response among women with mean age 35 and normal FSH. Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;27:362–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broer SL, Mol BW, Hendriks D, Broekmans FJ. The role of antimullerian hormone in prediction of outcome after IVF: comparison with the antral follicle count. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(3):705–14. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.La Marca A, Nelson SM, Sighinolfi G, Manno M, Baraldi E, Roli L, et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone-based prediction model for a live birth in assisted reproduction. Reprod BioMed Online. 2011;22(4):341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holte J, Brodin T, Berglund L, Hadziosmanovic N, Olovsson M, Bergh T. Antral follicle counts are strongly associated with live-birth rates after assisted reproduction, with superior treatment outcome in women with polycystic varies. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:594–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iliodromiti S, Kelsey TW, Wu O, Anderson RA, Nelson SM. The predictive accuracy of anti-Müllerian hormone for live birth after assisted conception: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(4):560–70. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arce JC, Klein BM, La Marca A. The rate of high ovarian response in women identified at risk by a high serum AMH level is influenced by the type of gonadotropin. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(6):444–50. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.892066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lukaszuk K, Kunicki M, Liss J, Lukaszuk M, Jakiel G. Use of ovarian reserve parameters for predicting live births in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;168:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodin T, Hadziosmanovic N, Berglund L, Olovsson M, Holte J. Antimüllerian hormone levels are strongly associated with live-birth rates after assisted reproduction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1107–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khader A, Lloyd SM, McConnachie A, Fleming R, Grisendi V, La Marca A, et al. External validation of anti-Müllerian hormone based prediction of live birth in assisted conception. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merhi Z, Zapantis A, Berger DS, Jindal SK. Determining an anti-Mullerian hormone cutoff level to predict clinical pregnancy following in vitro fertilization in women with severely diminished ovarian reserve. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(10):1361–5. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0077-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elter K, Kavak ZN, Gokaslan H, Pekin T. Antral follicle assessment after down-regulation may be a useful tool for predicting pregnancy loss in in vitro fertilization pregnancies. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005;21:33–7. doi: 10.1080/09513590500099313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH. Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) defines, independent of age, low versus good live-birth chances in women with severelydiminished ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2824–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]