Abstract

Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) presents with a variety of clinical phenotypes including motor impairments such as gait dysfunction, rigidity, tremor and bradykinesia as well as cognitive deficits including personality changes and dementia. In recent years, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor gene (CSF1R) has been identified as the primary genetic cause of HDLS. We describe the clinical and neuropathological features in three siblings with HDLS and the CSF1R p.Arg782His (c.2345G > A) pathogenic mutation. Each case had varied motor symptoms and clinical features, but all included slowed movements, poor balance, memory impairment and frontal deficits. Neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging revealed atrophy and increased signal in the deep white matter. Abundant white matter spheroids and CD68-positive macrophages were the predominant pathologies in these cases. Similar to other cases reported in the literature, the three cases described here had varied clinical phenotypes with a pronounced, but heterogeneous distribution of axonal spheroids and distinct microglia morphology. Our findings underscore the critical importance of genetic testing for establishing a clinical and pathological diagnosis of HDLS.

Keywords: Leukoencephalopathy, Microglia, HDLS, CSF1R, Frontotemporal degeneration, Corticobasal syndrome, Dementia with Lewy bodies

Background

Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) is a rare, autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative disease that presents with diverse phenotypes including motor impairments such as gait dysfunction, rigidity, tremor and bradykinesia along with cognitive impairments like personality changes and dementia [1]. The onset of symptoms is usually in the fourth or fifth decade, progressing to dementia and death within 5–10 years. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically shows patchy cerebral white matter abnormalities [2]. A definite diagnosis of HDLS requires pathology demonstrating widespread myelin loss and abundant axonal spheroids. Since the discovery of mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor gene (CSF1R) that are pathogenic for HDLS [3], genetic screening of CSF1R has increased the number of individuals diagnosed with HDLS [4–9]. Here we describe the clinical and neuropathological features of three siblings with a previously published pathogenic CSF1R mutation, p.Arg782His [1].

Genetics

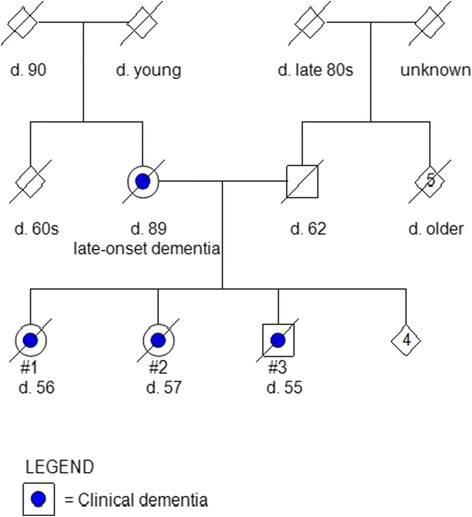

Targeted next-generation sequencing was performed alongside histology, immunohistochemistry and microscopic analyses of the brain tissue [10]. A heterozygous missense mutation c.2345G > A (p.Arg782His, rs282860281) was identified in exon 18 of CSF1R (Fig. 1) in all three symptomatic siblings (Fig. 2). Other neurodegenerative disease-associated gene mutations were excluded and the mutation was confirmed by genotyping using a custom TaqMan allelic discrimination assay (Life Technologies). The family history is notable for late-onset dementia in the mother at the age of 89 (Fig. 2) and a father who died at age 62 of unrelated causes. Of note, a paternal first cousin once removed may have had symptoms similar to Case #1 (not shown in pedigree). The genetic status of four additional living siblings shown in the pedigree is not provided for privacy reasons. Because of the father’s relatively early death and the fact that neither parent’s DNA was available to test, the penetrance of the mutation cannot be fully assessed.

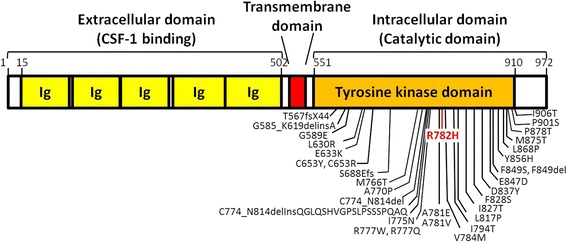

Fig. 1.

CSF1R protein domain and mutation schematic. Schematic diagram of the protein domain structure of CSF1R with amino acid numbers provided. Mutations previously reported in other studies are shown in black [3–5, 7–9] and the R782H mutation identified in the present study is highlighted in red. Ig: Immunoglobulin domains

Fig. 2.

Family Pedigree. A three-generation pedigree of the family is shown. The symbols for individuals symptomatic with any form of dementia are filled with blue circles. Deceased individuals have a slash mark with age at death (d.) indicated. Diamond shapes are intended to mask gender for privacy protection. A number within a pedigree symbol indicates the number of additional individuals in that generation

Case presentations

All three cases presented with slowed movement, poor balance and cognitive deficits (Table 1). Gait disturbances included retropulsion and postural instability, without tremor, rigidity or cog-wheeling. Early behavioral changes included impulsiveness and disinhibition. MRIs from the three patients were reviewed by several neurologists with expertise in neurodegenerative diseases as well as neuroradiologists. The most consistent finding was increased signal on FLAIR and T2-weighted images in the periventricular and deep white matter; volumetric measurements were not available. Ultimately, the MRI findings were supportive of, but not distinctive for, HDLS, although the MRI pulse sequences were not optimized for the detection of calcifications and other distinctive markers. Case #1, a female in her late 40s, developed depression and difficulty with cognition in addition to motor impairments, and was unable to work after approximately one year. She was noted to be increasingly emotionally labile. Examination at age 52 demonstrated a pseudobulbar affect. Her short-term memory was only mildly impaired, but she exhibited poor emotional regulation, perseveration and a deficit in set-shifting. For example, she was unable to perform the oral version of the Trail Making Test on which she was required to produce an ascending sequence of alternating letters and numbers (e.g., A-1-B-2…). Clinically, she was thought to have frontotemporal degeneration (FTD). Case #2 was a woman in excellent health until age 55. When first evaluated neurologically both mild memory problems and limited use of her left hand were noted. Her personality and behavior were mildly altered in that she was slightly labile emotionally. Examination demonstrated normal cognition except for a moderate impairment in short-term word memory. She had clear but subtle parietal deficits including left visual extinction and a mild left motor neglect manifested as failure to use her left arm unless instructed to do so. There was a mild decrease in left hand dexterity. Her clinical diagnosis was corticobasal syndrome (CBS). Case #3 was a man who presented with symptoms that began in his early 50s. He was found to have poor judgment at work and trouble balancing his checkbook. He became disabled after two years. On examination he exhibited prominent frontal deficits including distractibility, perseveration and mild emotional lability. Memory and visuo-spatial function were poor, with left visual extinction. By MRI, there was thinning of the corpus callosum which was not clearly evident in the other subjects. Clinically, his diagnosis was dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and parkinsonism. In all three instances, cognitive/behavioral and motor deficits worsened slowly and relentlessly over several years; subjects were not examined by the authors in their terminal states.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of individuals with the CSF1R p.Arg782His mutation

| Case | Sex | Origin | Onset age | Age at death | Initial symptoms | Affected family members | Prominent pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | F | USA | late 40’s | 56 | Cognitive decline, depression, slowed movement | 3 siblings | Severe dorsolateral frontal white matter loss, disrupted axons, axonal spheroids |

| 2a | F | USA | 54 | 57 | Poor balance, cognitive and memory decline, slowed movement | 3 siblings | Severe orbital frontal white matter loss, disrupted axons, axonal spheroids |

| 3a | M | USA | early 50’s | 55 | Poor balance, cognitive decline, slowed movement | 3 siblings | Severe orbital frontal and parietal white matter myelin loss, disrupted axons, axonal spheroids |

| 4 | F | Japan | 51 | - | Cognitive decline, aphasia, epileptic seizures | 3 uncles, cousin | Disrupted axons, axonal spheroids (biopsy) |

| 5 | F | USA | 51 | - | Cognitive and memory decline | 3 aunts | Disrupted axons, axonal spheroids (biopsy) |

| 6 | F | Korea | 37 | 42 | Poor balance, stuttering, dysarthria | sibling, mother, uncle | Frontal and parietal white matter myelin loss, disrupted axons, axonal spheroids |

aCases reported in this study

Neuropathology

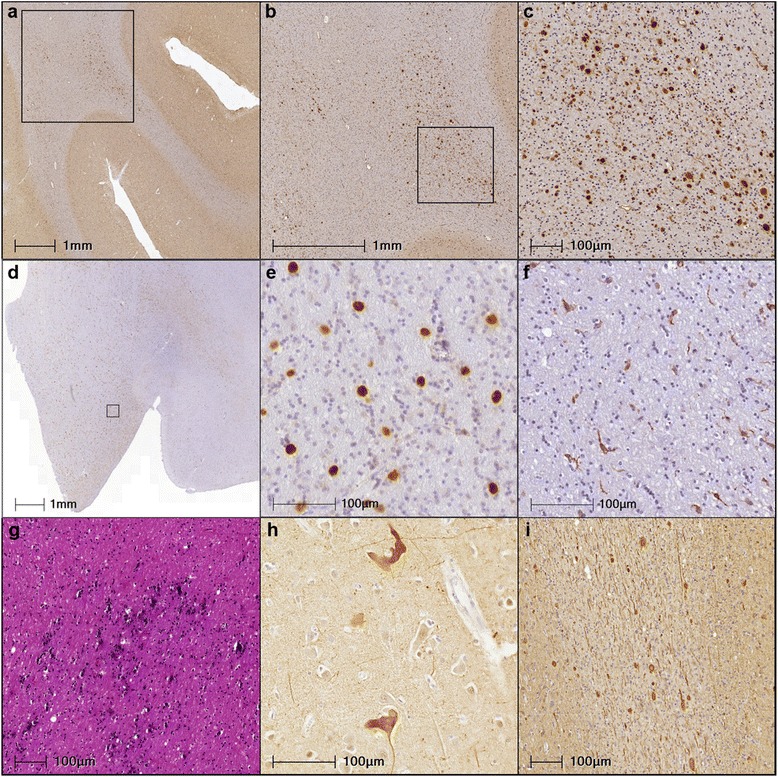

Each case showed abundant white matter Aβ precursor protein (APP) positive spheroids that were heterogeneously distributed in subcortical regions (Figs. 3 and 4a-c). These spheroids were also observed by neurofilament (Fig. 4i), tau and ubiquitin antibodies and H&E (not shown). The spheroids were more numerous in deep white matter with the U-fibers relatively spared (Fig. 4a). Phagocytic cells (macrophages and microglia) were also heterogeneously distributed in the subcortical white matter and these cells showed highly varied and distinctly unusual morphologies. The most distinctive morphology was characteristic of activated phagocytic macrophages (Fig. 4d-e) that were strongly positive for CD68, but not Iba1 positive. Other, Iba1 positive microglia had a more classic microglia shape (Fig. 4f). Prominent spongiosis in neocortical regions was another common feature. Neither TDP-43 nor α-synuclein inclusions were observed.

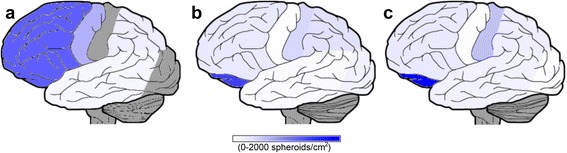

Fig. 3.

Axonal spheroids were heterogeneously distributed throughout the subcortical white matter across all three subjects. Lateral representations display the relative burden of the subcortical white matter spheroid pathology as density measurements for Cases #1-3 that are mapped to different cortical regions (a-c respectively). Densities of the APP positive spheroids were obtained from counts and surface areas generated by white matter regions of interest in NIH’s ImageJ 1.49. Dark grey areas indicate regions where densities were not obtained

Fig. 4.

Common neuropathological features of the 3 cases of HDLS studied here. Spheroids were abundant (a) primarily in the deeper white matter without affecting the short association fibers; b spheroids had a heterogeneous distribution as is evident by comparing the left and right side of the image; c focal very dense clusters of spheroids were seen (Case #3, orbital frontal cortex). d Microglia were not diffusely distributed and were of two distinct populations. Many microglia had morphologies indicative of (e) activated phagocytic macrophages that were CD68 positive and Iba1 negative with unusually ramified morphologies (f) while others were Iba1 positive microglia with more simple morphologies (Case #2, anterior corpus callosum). Occasionally, additional pathologies included (g) patches of calcifications (Case #2, blue-black splotchy areas in the anterior corpus callosum) and (h) irregular neuronal accumulations of pathological tau (Case #3, anterior cingulate). i Spheroids could also be visualized by tau, ubiquitin and α-synuclein antibodies (not shown here as well as by anti-neurofilament antibodies (shown here for Case #1 in the angular gyrus). Antibodies and stains used: (a-c) 22c11, (d-e) CD68, (f) Iba1, (g) H&E, (h) PHF1, (i) RMO24.9

Case #1’s gross examination revealed severe frontal and temporal atrophy with severe ventricular enlargement and a 1092 g brain weight. Microscopically, besides the numerous spheroids (Fig. 3a), additional pathology included obvious neuronal loss and degeneration of long axonal projections, extensive cell loss and gliosis with relative sparing of the granule cells in the hippocampus, rare Aβ plaques and focal cortical amyloid angiopathy (CAA), but no neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). Case #2 had moderate frontal atrophy with mild ventricular enlargement and weighed 1338 g. There were focal areas of dystrophic calcification and mild demyelination in the corpus callosum (Fig. 4g) and entorhinal cortex that were not apparent in the MRI. Rare ballooned neurons were noted in the cingulate, along with tau-positive grains and neurites in limbic areas, occasional tau-positive coiled bodies, mild CAA without Aβ plaques and NFTs in the medial temporal lobe. Case #3 had mild, diffuse atrophy with mild ventricular enlargement and weighed 1278 g. The limbic regions and brainstem were relatively spared, although spheroids were observed in the medulla. Similar to Case #2, irregular, tau-positive ballooned neurons were also noted in the cingulate (Fig. 4h) while no Aβ plaques were seen but some NFTs were present only in the entorhinal cortex.

Conclusions

Abundant white matter spheroids and CD68-positive macrophages were the predominant pathologies in these cases. Cases #2 and #3 had rare ballooned neurons, coiled bodies and tau-positive grains and neurites, which are found in other tauopathies such as corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick’s disease and argyrophilic grain disease [11]. What role pathological tau plays in HDLS has yet to be determined.

The p.Arg782His mutation has been previously reported in three families from Japan (Case #4) [12], USA (Case #5) [13] and Korea (Case #6) [14]. The clinical similarities and differences of our three cases and the additional published cases with the same mutation are highlighted in Table 1. Cognitive difficulties were noted for all cases. Our three patients all presented with slowed movements, as did Case #6 in the Table, but Cases #4 and #5 did not. Postural instability was also common, although this was a late symptom for Case #5. The motor deficits in Cases #4 and #6 were eventually severe, while the others had relatively mild impairments.

CSF1R is a key regulator of myeloid lineage cells and microglia in the adult brain [15] and HDLS-associated CSF1R mutations are all located in the protein’s tyrosine kinase domain. Experimental evidence indicates that these mutations cause loss of function [16, 17]. CSF1R mutations may also result in haploinsufficiency [18] which, in mice, causes a HDLS-like phenotype [19]. CSF1R’s role as a microglial regulator and the functional deficits associated with CSF1R mutations supports the hypothesis that microglia dysfunction may precede the accumulation of axonal spheroids in HDLS. Here we present three familial cases with full neuropathological characterization that demonstrate the range of pathology and clinical phenotypes that can be seen in individuals with the same CSF1R mutation. Since the three siblings studied here were diagnosed clinically with FTD, CBS, and DLB, our findings underscore the critical importance of genetic testing for establishing a clinical and pathological diagnosis of HDLS.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from next of kin in accordance with institutional review board guidelines of the University of Pennsylvania.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) Grant PO1 AG017586 and P30 AG010124. We would like to thank the family of the patients studied here for their meaningful contributions that made this study possible.

Abbreviations

- HDLS

Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CSF1R

Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor gene

- FTD

Frontotemporal degeneration

- CBS

Corticobasal syndrome

- DLB

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- CAA

Cortical amyloid angiopathy

- NFTs

Neurofibrillary tangles

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JR drafted the manuscript. KR performed the immunohistochemistry and quantification. ES performed the genetic analysis. EW obtained the family history. EL and JT were the neuropathologists. HC was the clinician and helped draft the manuscript. VL participated in the study’s design. VV conceived of the study and helped draft the manuscript. All were involved in critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Sundal C, Lash J, Aasly J, et al. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS): a misdiagnosed disease entity. J Neurol Sci. 2012;314:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bender B, Klose U, Lindig T, et al. Imaging features in conventional MRI, spectroscopy and diffusion weighted images of hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS) J Neurol. 2014;261:2351–9. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rademakers R, Baker M, Nicholson AM, et al. Mutations in the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) gene cause hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Nat Genet. 2012;44:200–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battisti C, Di Donato I, Bianchi S, et al. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids: three patients with stroke-like presentation carrying new mutations in the CSF1R gene. J Neurol. 2014;261:768–72. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerreiro R, Kara E, Le Ber I, et al. Genetic analysis of inherited leukodystrophies: genotype-phenotype correlations in the CSF1R gene. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:875–82. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karle KN, Biskup S, Schüle R, et al. De novo mutations in hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS) Neurology. 2013;81:2039–44. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436945.01023.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed R, Guerreiro R, Rohrer JD, et al. A novel A781V mutation in the CSF1R gene causes hereditary diffuse leucoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:141–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Piana R, Webber A, Guiot M-C, et al. A novel mutation in the CSF1R gene causes a variable leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Neurogenetics. 2014;15:289–94. doi: 10.1007/s10048-014-0413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsui J, Matsukawa T, Ishiura H, et al. CSF1R mutations identified in three families with autosomal dominantly inherited leukoencephalopathy. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet Off Publ Int Soc Psychiatr Genet. 2012;159B:951–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toledo JB, Van Deerlin VM, Lee EB, et al. (2013) A platform for discovery: The University of Pennsylvania Integrated Neurodegenerative Disease Biobank. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dickson DW, Kouri N, Murray ME, Josephs KA. Neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration-tau (FTLD-tau) J Mol Neurosci MN. 2011;45:384–9. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9589-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinoshita M, Yoshida K, Oyanagi K, et al. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids caused by R782H mutation in CSF1R: case report. J Neurol Sci. 2012;318:115–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholson AM, Baker MC, Finch NA, et al. CSF1R mutations link POLD and HDLS as a single disease entity. Neurology. 2013;80:1033–40. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim E-J, Shin J-H, Lee JH, et al. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia linked CSF1R mutation: Report of four Korean cases. J Neurol Sci. 2015;349:232–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elmore MRP, Najafi AR, Koike MA, et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor signaling is necessary for microglia viability, unmasking a microglia progenitor cell in the adult brain. Neuron. 2014;82:380–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiyoshi M, Hashimoto M, Yukihara M, et al. M-CSF receptor mutations in hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids impair not only kinase activity but also surface expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;440:589–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pridans C, Sauter KA, Baer K, et al. (2013) CSF1R mutations in hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids are loss of function. Sci Rep. doi: 10.1038/srep03013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Konno T, Tada M, Tada M, et al. Haploinsufficiency of CSF-1R and clinicopathologic characterization in patients with HDLS. Neurology. 2014;82:139–48. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chitu V, Gokhan S, Gulinello M, et al. Phenotypic characterization of a Csf1r haploinsufficient mouse model of adult-onset leukodystrophy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) Neurobiol Dis. 2014;74C:219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]