Abstract

Background and objective

To ensure that decisions to start and stop dialysis in ESRD are shared, the factors that affect patients and health care professionals in making such decisions must be understood. This systematic review sought to explore how and why different factors mediate the choices about dialysis treatment.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and PsychINFO were searched for qualitative studies of factors that affect patients’ or health care professionals’ decisions to commence or withdraw from dialysis. A thematic synthesis was conducted.

Results

Of 494 articles screened, 12 studies (conducted from 1985 to 2014) were included. These involved 206 patients (most receiving hemodialysis) and 64 health care professionals (age ranges: patients, 26–93 years; professionals, 26–61 years). For commencing dialysis, patients based their choice on "gut instinct," as well as deliberating over the effect of treatment on quality of life and survival. How individuals coped with decision-making was influential: Some tried to take control of the problem of progressive renal failure, whereas others focused on controlling their emotions. Health care professionals weighed biomedical factors and were led by an instinct to prolong life. Both patients and health care professionals described feeling powerless. With regard to dialysis withdrawal, only after prolonged periods on dialysis were the realities of life on dialysis fully appreciated and past choices questioned. By this stage, however, patients were physically dependent on treatment. As was seen with commencing dialysis, individuals coped with treatment withdrawal in a problem- or emotion-controlling way. Families struggled to differentiate between choosing versus allowing death. Health care teams avoided and queried discussions regarding dialysis withdrawal. Patients, however, missed the dialogue they experienced during predialysis education.

Conclusions

Decision-making in ESRD is complex and dynamic and evolves over time and toward death. The factors at work are multifaceted and operate differently for patients and health professionals. More training and research on open communication and shared decision-making are needed.

Keywords: CKD, dialysis, dialysis withholding, end-stage kidney disease, quality of life

Introduction

Dialysis brings high treatment burden to patients and families, considerable costs to health services, and high mortality. Sixty-five percent of patients die within 5 years (1). Over three quarters of those with ESRD are treated with dialysis (2); however, decisions on whether to start, continue, or stop dialysis remain poorly informed by evidence and rely predominantly on observational studies, with all their inherent limitations (3–5).

To help patients, families, and health care professionals make joint decisions about dialysis treatment, clinical practice guidelines were developed by the Renal Physicians Association (RPA) for shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis (6). These support patient preferences while acknowledging the limitations in the evidence. A large number of quantitative studies have looked at physiologic (7–10), social (8,10–14), educational (15–17), and geographic factors (18) that influence the decision to commence and withdraw from dialysis (15–22). These studies have provided insights into influential factors, but their largely survey-based methods do not further our understanding of why and how different factors operate.

Qualitative research provides an in-depth and interpreted understanding of the factors that affect decision-making, with a focus on how and why patients and health care professional make sense of their experiences and perspectives (23). An inductive approach can help determine new hypotheses and theories for subsequent empirical testing (23). Two systematic reviews (24,25) of qualitative studies in this area have examined factors that influence patient decisions, but factors that affect health care professionals and their interactions with patients in the decision-making process are still largely unexplored. Because health care professionals and patients are partners in the shared decision model advocated by the RPA (6) and National Service Framework (2005) (26), this is an important gap in the current evidence-base.

To address this gap, this systematic review aimed to identify and synthesize existing qualitative research in order to explore how and why different factors influence patients and health care professionals in the decision to commence and withdraw dialysis as ESRD progresses. The synthesis of primary qualitative studies creates a cumulative body of evidence that builds and develops theory for practice in ways that individual studies cannot (27). This will therefore further our understanding of how decisions are made in this context and how effective shared decision-making can be facilitated.

Materials and Methods

Selection Criteria

Participants included in the studies were adult patients with CKD who had decided for or against dialysis. Studies that explored health care professionals’ views of caring for such patients during the decision-making process were also included. This group included physicians, dialysis nurses, student nurses, and social workers.

Literature Search

Medical Subject Heading terms and text words for ESRD, dialysis, conservative kidney management and decision-making were combined with validated terms for qualitative studies (Supplemental Material) (28).The search was performed in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and PsychINFO and was last updated in May 2014. Reference lists of relevant papers and contents pages of relevant journals were searched. Two researchers independently assessed titles, abstracts, and full text against the inclusion criteria.

Quality Appraisal

All papers were assessed against Hawker and colleagues' appraisal checklist (29). Inter-rater agreement was assessed on a purposive selection of five studies with a range of scores (κ=0.9).

Synthesis of Findings

The papers were synthesized systematically using thematic synthesis (30), an established and widely used method of analyzing qualitative research. This synthesis was approached from a realist perspective and aimed to provide recommendations for clinical practice. This school of thought considers reality to exist independent of those observing it but recognizes the importance of understanding the participants’ own interpretation of events (31). Because thematic analysis is not restricted theoretically and enables both inductive and deductive analysis, it provides an appropriate method for such a synthesis. The analysis was managed using ATLAS.ti (version 7) and reported in accordance with the Enhancing Transparency in REporting the synthesis of Qualitative research (ENTREQ) guidance (32).

Results

Literature Search and Study Descriptions

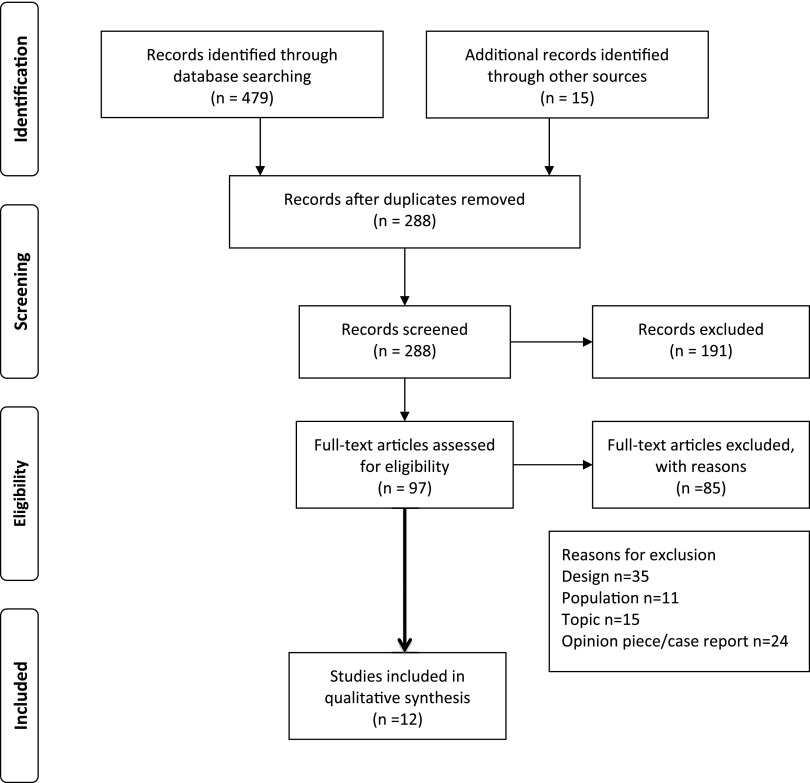

Of the 494 articles screened, 12 studies involving 206 patients and 64 health care professionals were included in the synthesis (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the studies included in the review, and Table 2 illustrates how many codes, items of evidence, and papers contributed to each theme. Most studies were conducted between 1997 and 2014 and in Europe (n=5) (33–37) and the United States (n=5) (38–42). The remainder were performed in Australia (43) and Taiwan (44). Five studies were conducted in single-payer health care systems (33,34,36,37,44), two in two-tier systems (35,43), and five in a country with an insurance mandate (38–42). Researchers, independent of the health care team and patient, conducted all interviews, focus groups, and observations.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the review

| Study | Aim | Population | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aasen et al. (33), 2012 Location: Norway | Explore how elderly patients with ESRD undergoing hemodialysis, perceive patient participation in decision-making Patient view | n=188 patients who had had dialysis for 2 mo; of these, 11 were recruited Patients: Ages: 1 patient was 72 yr, 2 were 75–78 yr, 6 were 80–85 yr, and 2 were 90 yr Sex: 4 women/7 men Ethnicity: Not reported Education level: 2 patients had higher level, 3 had lower level, 6 had no education | Critical discourse analysis Data collection:open-ended qualitative interview Patients recruited from 5 hospitals by nurses | 2 discourses identified: (1) The health care team's power and dominance and (2) the patient’s struggle for shared decision making The elderly patient’s right to participate in dialysis treatment did not seem to be well incorporated into the social practices of the unit |

| Ashby et al. (43), 2005 Location: Australia | To explore the reasons why some patients choose to stop or not start dialysis and the personal and social effects of this decision Patient/carer view | n=52; of these, 41 were ineligible Response number, 11, resulting in 16 interviews Patients and carers: Age: mean, 77 yr (range, 57–89 yr) Sex: 9 women/7 men Ethnicity: 3 from non–English-speaking backgrounds Education level: Not recorded | Grounded theory Data collection: semi-structured interviews Recruited from 2 tertiary center hospitals | Reasons given included: Not to burden others, experience of deteriorating quality of life, prognostic uncertainty, sense of abandonment |

| Breckenridge, 1997 (38) Location: United States | To elicit patient’s perceptions of why, how and by whom their dialysis treatment was chosen Patient view | n=22 Patients: Age: Mean, 53.8 yr (29–69) Sex: 9 women/13 men Ethnicity: 17 black/5 white Education level: Not recorded | Grounded theory Data collection: Semi-structure interviews Recruited from 4 dialysis units | 11 themes identified: Self decision; access-rationing decision; significant other decision; to live decision; physiologically dictated decision; expert decision; to be care for decision; independence versus dependence decision; no patient choice in making decision; patient preference/choice; and switching modalities due to patient preference/choice. |

| Halvorsen et al. (34), 2008 Location: Norway | Explore the priority dilemmas in dialysis treatment and care offered to elderly patients Health professional view | n=9 (5 physicians and 4 nurses) Physicians and nurses: Age: Physician range, 48–61 yr; nurse range, 26–55 yr Sex: 7 women/2 men Ethnicity: Not recorded Experience level: Physicians, 17–30 yr; nurses, 4–30 yr | Hermeneutical analysis Data collection: Semi-structured interviews Recruited from part of a larger multisite study on healthcare for elderly patients | Dilemmas concerning withholding and withdrawing treatment Advanced age is rarely an absolute or sole priority criterion Nurses prioritize specialized dialysis care and not comprehensive nursing care; thus, the complex needs for elderly patients are not always met |

| Kaufman et al.(39), 2006 Location: United States | To describe the sociomedical features of treatment that shape provider understanding of the nature of choice and no choice; to illustrate the effects of treatment patterns and provider practices on patients’ perceptions of their options for treatment and for life extension. Patients with cardiac disease and renal transplantation were also studied. Patients/health professional view | n=18 renal health professionals, 43 dialysis patients Patients and health professionals: Age: 70–93 yr Sex: Not reported Ethnicity: Diverse Education level: Not reported | Ethnography Data collection: Interviews and observation in dialysis clinics Recruited from clinics using snowball sampling; part of a larger study | Neither patients nor the health professionals made choices about the start or continuation of life-extending treatment that were uninformed by the following: routine pathways of treatment; pressures of technological imperative; or growing normalization, ease, and safety of treating older patients |

| Kelly-Powell (40), 1997 Location: United States | To explore the experiences of adults with potentially life-threatening conditions in their decisions regarding treatment options; included cardiac, cancer and renal conditions Patient view | n=18 patients recruited, 9 of whom had renal failure Patients: Age: Range, 26–81 yr Sex: 9 women/9 men Ethnicity: 15 white, 2 black, 1 Native American Education level: Not recorded | Grounded theory Data collection: Interviews Recruited from large urban teaching hospital, outpatient dialysis center, family practice | Patients make decisions about treatments based on a broad set of values and beliefs which may have little to do with effectiveness of a treatment and more to do with perceived impact of treatment on personal lives and their families |

| Lelie et al. (35), 2000 Location: The Netherlands | Identification of the general practical rules, norms, and values underlying therapeutic decisions. Focused on what the physician considered to be good usual care Patient/health professional interaction | n=59 interactions observed between 30 patients and 4 nephrology residents and 1 attending physician Age: Not reported Sex: Not reported Ethnicity: Not reported Education level: Not reported | Methodologic approach not described Data collection: observation physician and patient interaction while discussing dialysis therapy Recruited from outpatient clinic; part of a larger study | Choice of therapy was discussed as a choice and was discussed months in advance; patient perceptions were considered important Moral persuasion was allowed No patients were informed that dialysis is more expensive and poses allocation problems When to start treatment is not discussed in a shared manner There was evidence of differing approaches to the young, elderly, and severely ill and patients with multiple comorbidities |

| Lin et al. (44), 2005 Location: Taiwan | To describe the experiences of making a decision about hemodialysis among a group of Taiwanese with ESRD Patient view | n=12 Patients: Age: Mean, 38.9 yr; range 28–53 Sex: 6 women/6 men Ethnicity: Taiwanese Education level: Educated to high school level | Colaizzi's phenomenological method Data collection: Semi-structured interviews Recruited from dialysis centers | Three broad categories were identified: 1. Confronting the dialysis treatment: Fear was thought to be caused by false belief, threat to life, impairment of self concept, fear of physical limitations 2. Seeking further information: Patients sought opinions of family, professional confirmation, and explored alternatives 3. Living with dialysis: Patients discussed worsening symptoms, family support, and cultural beliefs about the cause of their illness |

| Noble et al. (36), 2009 Location: United Kingdom | To understand the decision to not embark on dialysis Patient/carer view | n=30 patients and 17 caregivers Patients and caregivers: Age: Not reported Sex: Not reported Ethnicity: Not reported Education level: Not reported | Constant comparative Data collection: Observation of naturally occurring consultations Recruited from clinic; part of a larger study | Seventeen felt they made an autonomous decision Seven had no option but to refuse because it would have been of no benefit and would have ultimately caused their death Two opted for medical management without dialysis and felt both would result in the same outcome Four thought there was no decision to be made |

| Russ et al. (41), 2007 Location: United States | To explore the value of an extended old age made possible by dialysis Patients/health professional view | n= 21 health professionals (4 physicians, 5 nurses, 5 social workers, 2 dieticians, 2 technicians, 3 administrators), 43 patients, 7 family members Patients: Age: >70 yr Sex: 27 women/16 men Ethnicity: 24 white, 13 black, 5 Asian, 1 Latino Education level: Not reported | Grounded theory Data collection: Interviews and observations of consultations Recruited from 2 dialysis units | Most elderly patients did not want or choose dialysis Neither, however, did they want to die Most grudgingly accept treatment until the burdens were considered to outweigh the benefits, when family and health care professionals initiated discontinuation. There was evidence of some patients discussing withdrawal proactively; however, these were the exception. Most patients question life on dialysis but choose to withdraw from treatment later |

| Schell et al. (42), 2012 Location: United States | To describe how nephrologists and older patients discuss and understand the prognosis and course of kidney disease leading to renal replacement therapy Patients/health professional view | n=11 nephrologists and n=29 patients Patients and health professionals: Age: CKD, 68 yr; HD, 72 yr; nephrologist, 50 yr Sex: CKD, 64% male; HD, 50% male; nephrologist, 90% male Ethnicity: CKD, 55% white; HD, 28% white; nephrologist, 73% white Education level: Not reported | Methodologic approach s not described Data collection: Focus groups and interviews Recruited from academic and community nephrology units | Six themes: 1.Patients are shocked by diagnosis 2. Patients are uncertain about how their disease will progress 3. Patients lack preparation for living with dialysis 4. Nephrologists struggle to explain illness complexity 5. Nephrologists manage a disease over which they have little control 6. Nephrologists tend to avoid discussions of the future Discussions about prognosis are rare Patients focused on the future to help them cope with the present Nephrologists were concerned about upsetting patients |

| Tweed and Ceaser (37), 2005 Location: United Kingdom | To assess the decision-making process by predialysis patients Patient view | n=9 Patients: Age: Mean, 54 yr (range, 29–69 yr) Sex: 4 women/5 men Ethnicity: Not reported Education level: Not reported | Interpretative phenomenologicanalysis Data collection:Semi-structured interviews Recruited from predialysis clinic | Four main themes: 1. Maintaining ones integrity and preserving normality was important 2. Patients felt they were forced to adapt to treatment 3. Individuals received support and information through peers 4. Staff provided support. and the experience of illness shaped beliefs about renal disease and treatment options These themes emerged regardless of the treatment chosen |

HD, hemodialysis.

Table 2.

Formation of themes

| Overarching Theme | Theme | No. of Codes Associated with Theme | No. of Items of Evidence Associated with Theme | No. of Papers Associated with Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commencing or withholding | ||||

| Patient factors | Deliberation of factors | 45 | 228 | 11 |

| Gut instinct | 28 | 45 | 10 | |

| Coping mechanisms | 34 | 61 | 9 | |

| Health care team factors | Biomedical criteria | 17 | 62 | 11 |

| Ethical dilemma | 6 | 17 | 2 | |

| Patient and health care team interaction | Power and communication | 71 | 124 | 10 |

| Dialysis withdrawal | ||||

| Life on dialysis | Experiential knowledge | 42 | 30 | 9 |

| Patient factors | Facing withdrawal | 39 | 62 | 8 |

| Family influence | 7 | 29 | 5 | |

| Health care team factors | Avoidance | 49 | 67 | 4 |

| Genuine request | 10 | 15 | 3 | |

| Patient and health care team interaction | Doing trumps talking | 29 | 34 | 7 |

| If not now, when? | 19 | 7 | 5 |

Quality Appraisal

Hawker and colleagues' (29) quality assessment scores ranged from 21 to 33 (Table 3), which indicated fair to good quality of all studies.

Table 3.

Summary of Hawker and colleagues' quality assessment scores for included studies (28)

| Study | Abstract/Titles | Introduction/Aims | Method/Data | Sampling | Data Analysis | Ethics/Bias | Results | Transferability/Generalizability | Usefulness | Total Score Out of 36 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaufman et al. (39), 2006 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 |

| Breckenbridge (38), 1997 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 33 |

| Schell et al. (42), 2012 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 32 |

| Lin et al. (44), 2005 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 32 |

| Kelly-Powell (40),1997 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 30 |

| Aasen et al. (33), 2012 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 28 |

| Russ et al. (41), 2007 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 28 |

| Ashby et al. (43), 2005 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 27 |

| Halvorsen et al. (34), 2008 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 24 |

| Tweed and Ceaser (37), 2005 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 23 |

| Noble et al. (36), 2009 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 22 |

| Lelie et al. (35), 2000 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

Scores for each category are out of 4, with 1=very poor; 2=poor; 3=fair, and 4=good.

Synthesis

The decision-making process evolved as patients progressed along their disease trajectory. The factors and how they influence choice are presented according to the decision whether to start dialysis and withdraw from treatment. These are presented as patient factors, health care professional factors, and their interaction (see Table 4 for exemplars).

Table 4.

Factors affecting decision-making themes and exemplars

| Factor | Exemplar |

|---|---|

| Commencing and withholding dialysis: patient factors | |

| Deliberation of factors | Past personal experience: “I’ve gone through heart surgery without any problem…I figured that I could stand it (dialysis) no matter what without any trouble.” [Kelly-Powell, 1997 (40)] |

| Illness experience: “I vomited all night; tea, medicine, everything I ate. It was painful. I stayed up all night… I told my husband I couldn’t take it anymore.” (Woman) [Lin et al., 2005 (44)] | |

| Peer experience: “You think you’re the only one in the world and I found there were lots of other people and people that were younger than me. I know it sounds awful but it helps me....” (Woman) [Tweed and Ceaser, 2005 (37)] | |

| “My brother… he was doing that for five years and I realise how hard it was for him to do it.” (Man) [Tweed and Ceaser, 2005 (37)] | |

| Being a burden: “Well I couldn’t see that it was really going to achieve anything apart from disrupting everybody’s life … I wouldn’t consider it under any circumstances.” (Woman, age 82 yr) [Ashby et al., 2005 (43)] | |

| Burden of treatment: “I made my decision … I couldn’t see meself going back and forth three times a week, waiting for a taxi to get home and there and waiting for a taxi to get back. No it’s not for me.” (Man, age 78 yr) [Ashby et al., 2005 (43)] | |

| Financial burden: “I think I’ll become a burden to my family and cause financial problems … You’ll ruin the family.” (Man, Taiwan) [Lin et al., 2005 (44)] | |

| “Dialysis treatment will be helpful, besides the health insurance pays for it” (Taiwan) [Lin et al., 2005 (44)] | |

| “I would pay anything for any helpful remedies.” (Taiwan) [Lin et al., 2005 (40)] | |

| Ethics- justice: “We are living longer and we are becoming quite a problem. In general we older people are presenting quite a problem. And it is a problem for us to know what to do.” (Woman, age 85 yr) [Ashby et al. 2005 (43)] | |

| Maintaining normal social roles: “If you can’t have some semblance of a normal life, then why would you want to live?” [Tweed and Ceaser, 2005 (37)] | |

| Family: “I became very ill. My mother was worried … She consulted those who had taken dialysis treatment. She was told it was all right and the patients were all in good condition. Finally, she urged me to receive it.” [Lin et al., 2005 (44] | |

| “My husband disagrees with the treatment. He was too busy to take me to the hospital. Besides, the kids need me.” [Lin et al., 2005 (44)] | |

| Culture and religion: “In the environment that we grew up in and how the families thought and … you pick a lot of that up and carry it through life… And I guess that’s one reason I could make that kind of decision.” [Kelly-Powell, 1997 (40)] | |

| “Physicians of western medicine tell you that dialysis treatment is the only solution. Chinese herb doctors are different. They’ll do their best to cure the illness.” [Lin et al., 2005 (44)] | |

| Spirituality: “a decision of the heart…” [Kelly-Powell, 1997 (40)] | |

| Quality of life before longevity: “If you are supposed to really follow that regime, I would rather cut a couple of years off my lifespan …There is almost nothing you can eat … I am not able to do this.” [Aasen et al., 2012 (33)] | |

| “At any rate… it defies explanation who finds the treatment bearable and who does not, this is the mystery of quality of life on dialysis.” (Health professionals) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| Gut instinct | Opt for life-prolonging treatment: “And they give you a choice…you can die now or you can die later. I chose later.” (Man, age 82 yr) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] |

| “I had no choice … I wanted to live.” [Kaufman et al., 2006 (39)] | |

| Accept dying as a natural course: “The idea of it that eventually it’s going to kill me it never phased me at all because I am at the downhill side of my life anyhow ... When my time comes I’ll just choof off and that’s it.” (Woman, age 82 yr) [Ashby et al., 2005 (43)] | |

| “So if I’m going to be fixed and all right, fine. If not, then I lived what I lived and I enjoyed what I had.”(Man, age 26 yr) [Kelly-Powell, 1997 (40)] | |

| Lesser of two evils: “I told my husband I couldn’t take it (symptoms) anymore. I would rather die. My husband took me to the hospital. I cried bitterly when I signed the agreement.” [Lin et al., 2005 (44)] | |

| “I suppose in the back of your mind you think, ‘I don’t want this’, cos you don’t want any of it really.” (Woman) [Tweed and Ceaser, 2005 (37)] | |

| Coping mechanism | Problem-controlling: “More you get use to it, the more you think about it and you think, ‘well, it’s not going to be a problem is it?’ You know, soon get round that” [Tweed and Caesar, 2005 (37)] |

| “It’s the difference between us and animals … we have the knowledge and free will; we can choose and act on that choice.” [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| Emotion-controlling: “I don’t know about anyone else, but the topic is really scary. I’d rather not hear the answer and whatever the answer is, I hope to outlive it.” [Breckenridge, 1997 (38)] | |

| “A big part of me says I’m going to stay stable and won’t have to do it (commence dialysis) … I’ll deal with it when it comes.” [Schell et al., 2012 (42)] | |

| Commencing and withholding dialysis: health care team factors | |

| Biomedical criteria | Medical criteria: “The decisive factor should be biological age and not chronological age.” [Halvorsen et al., 2008 (34)] |

| “If a patient had dementia or other severe malign diseases, the physicians were more restrictive about starting treatment.” [Halvorsen et al., 2008 (34)] | |

| Ethical dilemma | Unethical to prolong life: “It is not like I stand in a situation where I have to choose this patient and not that patient … rather … the situation is more about whether or not it is ethically right to prolong life at any price.”(Physician) [Halvorsen et al., 2008 (34)] |

| Patients continue to be offered treatment: “When I say no to treatment, it seems very decisive. It is difficult to make these decisions. It is a question of life and death.” (Physician) [Halvorsen et al., 2008 (34)] | |

| “My experience is that it is a lot easier to say yes than to say no, and that we start treatment on too many patients.” [Halvorsen et al., 2008 (34)] | |

| Commencing and withholding dialysis: patient and health care team interaction | |

| Power and communication | Power and dominance of the health care team: “These doctors always think they ought to decide and that I should listen to them. And maybe they are right because if I don’t then it may not end up so well…” [Aasen et al., 2012 (33)] |

| Health care professionals felt powerless: “You can do the best you can and know you are going to minimize (disease progression)… beyond that whatever is going to happen happens” [Schell et al., 2012 (42)] | |

| Patients felt uninformed: “People just don’t know what you got on your brain. You smiling (and) they think you’re not worried” [Schell et al., 2012 (42)] | |

| “I haven’t been told what the futures like except you go on dialysis every other day … You have to do it or you die.” [Schell et al., 2012 (42)] | |

| Presentation of risk: “In the clinics we observed, physicians and other staff framed the need for dialysis in terms of ‘when you will need to start dialysis’ and not ‘if.’” [Kaufman et al., 2006 (39)] | |

| “Well, we didn’t make it [decision], that’s what he said, she couldn’t have it. Basically, she could not be put on dialysis because of her heart. So I thought, you must know best.” [Noble et al., 2009 (36)] | |

| Communicating uncertainty: “… it was a guessing game sort of thing.” (Man, age 77 yr) [Ashby et al., 2005 (43)] | |

| “They can’t tell you, you know, how long you have to go … With all the modern stuff and all that, they still don’t know.” (Man, age 78 yr) [Ashby et al., 2005 (43)]. | |

| Who provided the information was important: “I just thought, ‘what the heck’ he should know what he’s doing.” [Kelly-Powell, 1997 (40)] | |

| Health care professionals influenced patient choice: “Don’t you want to continue living for your grandson? Don’t you want to see his children-don’t you want that for him? If you want to see his kids, you have to get a fistula this summer…”(Physician to patient) [Kaufman et al., 2006 (39)42] | |

| Dialysis withdrawal: patient factors | |

| Life on dialysis | “[I]t started with an emergency situation ... It’s presented as short-term treatment. It doesn’t click, wait a minute, this is full-on life support. And it was probably three years before she even started saying or admitting it was life support.” (Son) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] |

| “When they begin to see themselves as completely dependent on systems to keep them alive, that’s when you start hearing them talk about death and dying and they just don’t see themselves ‘going on this way’…”(Social worker) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| Facing withdrawal | Problem-controlling: “I have this tremendous control … one that people with cancer don’t have … Doctor said I’d probably live three to thirteen days without dialysis, and that it could be made very comfortable for me.” (Man, age 76 yr) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] |

| “It’s the only thing that makes it bearable … I don’t know if I will quit voluntarily, but I like to know I can.” [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| Emotion-controlling: “Most patients … are evasive in their answers, they say they ‘have to think about it’, they push it aside. They’re not willing to admit they want to give up.” (Nurse) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| “It’s rare someone actively discontinues … patients self-discontinue through passive-aggressive behaviour. Patients who pull out their catheter, or it just keeps coming out. ‘Cause they can’t directly say, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore. Take out my catheter. Make me comfortable.’” (Social worker) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| Family influence | Families found it difficult to make the decision to withdraw treatment: “The family won’t hear of it, so patients don’t feel they’re allowed to stop treatment.” (Social worker) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] |

| “Up till the end, she’d (patient) say ‘This is no way to live. You need to stop this.’ And we’re (family) going ‘We need to stop what? We’re not doing anything’… I’m not asking her to give up what she wants; I’m asking her to postpone it...” (Son) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| Dialysis withdrawal: health care team | |

| Avoidance | Health professionals’ difficulties in discussing withdrawal: “It’s hard to quantify how much someone will tolerate, what they will tolerate … or how they want to die.” [Nephrologist] [Schell et al., 2012 (42)] |

| “… [U]nhelpful to beat them over the head with mortality statistics.” [Nephrologist] [Schell et al., 2012 (42)] | |

| Caring relationship: “A patient who recalled being ‘nagged’ by nurses to come into dialysis agreed; she registered their entreaties as a ‘sign of caring.’” [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| “…[S]he doesn’t believe she has any quality of life. Yet … never once has she said, I think it’s time to stop. So I don’t say that either. Ever. You want your caregiver to get on the phone and say ‘get in here.’” (Dialysis nurse) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| Genuine request | Difficult to determine whether it is a genuine request for treatment withdrawal: “She’s miserable and feels dialysis is the culprit. But she doesn’t want to withdraw from dialysis; she wants to withdraw from the symptoms. It’s confusing because the signs of depression … get confused with the symptoms of dialysis.” [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] |

| Dialysis withdrawal: patient and health care team interaction | |

| Doing trumps talking | Patients missed dialogue: “One would think that it had to be in their interest to know what we think and maybe we could get some indications about how they think…it is much one-way communication … I haven’t experienced being asked about what we feel...” (Male) [Aasen et al., 2012 (33)] |

| “I want more information … Nurses do not tell me anything, other than blood percentages…” [Aasen et al., 2012 (33)] | |

| “They probably have got tired of me after so many years. Probably, they aren’t that interested anymore. It’s like I’ve become a piece of furniture.” [Aasen et al., 2012 (33)] | |

| Voting with their feet: “What is important on dialysis … is what you do, you keep showing up … Look, he keeps coming. Not regularly, but he’s here today. Sometimes a patient will say, maybe I won’t come in tomorrow … But then they’ll come in the next day or two, which always interests me-because that means they’re not really ready to stop.” [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| If not now, when? | Limit of frailty remains in the future: “The problem…(is that) no one wants to take responsibility for saying ‘no.’” (Nurse) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] |

| “Patients thus choose to be choosers … and they choose to choose later.” [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| “…most get so sick, they wind up in the hospital and it (withdrawal) just happens.” (Nurse) [Russ et al., 2007 (41)] | |

| “When you see that the patient coming in is not doing well, and is supposed to have dialysis no matter what … There is something about being allowed to die ... Sometimes I think we should have withdrawn the treatment a little earlier.” (Nurse) [Halvorsen et al., 2008 (34)] |

Commencing or Withholding Dialysis: Patient-Level Factors.

Deliberation of Factors

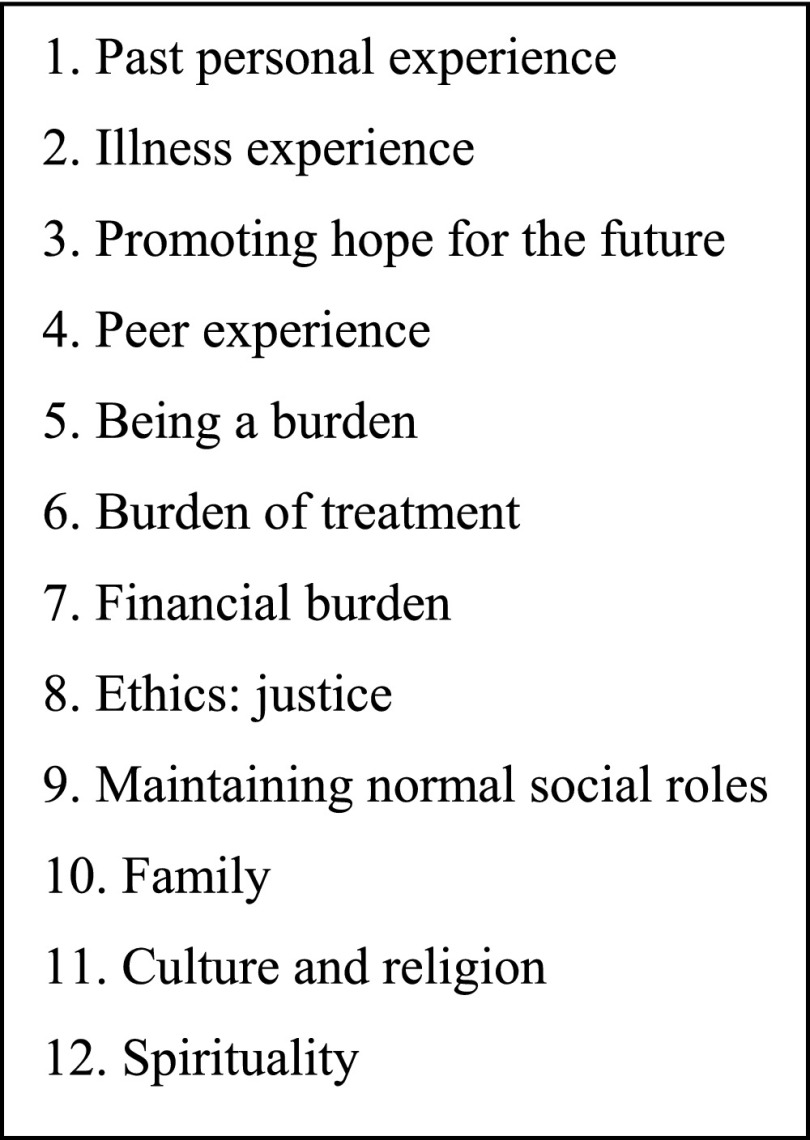

Patients considered a variety of factors when deciding whether to start dialysis, and these were different for each individual. Figure 2 illustrates the categories that contributed to this theme. Patients deliberated about the influence of the treatment choice on their quality of life (QoL) (33,34,36,37,40,41,43,44), which was then weighed against the survival benefits (33,34,36,37,41,43,44). Whether the effect on QoL outweighed survival advantage, or vice versa, was a personal judgment, and not something health care professionals and family members could predict (41). For many patients, the effect of treatment on QoL was more important than medical effectiveness (40), and maintaining a good QoL outweighed having a "long life" (33).

Figure 2.

Categories that contribute to the theme "deliberation of factors."

Gut Instinct

Patients also based the decision to start dialysis on their intuition on whether to opt for the life-prolonging treatment, regardless of the personal cost, or accept dying as a natural course, given the "loss of self-identity … source of great hardship and suffering, and a fragmentation of lifestyle" (44) associated with dialysis.

Some individuals did not have a strong instinct for either of these, and they described the choice as one between "two evils" (37,42,44). These patients considered dialysis to be the "lesser of two evils" (37), given their significant predialysis symptom burden and the inevitability of death without treatment. Nonetheless, it was not a decision these individuals wanted to make but one they were forced to make as their renal function deteriorated (37).

Coping Mechanisms

How individuals coped with the decision-making process was important. Two types of coping responses were evident (33,36,37,39–41,44): (1) control the problem and (2) control emotions. Problem-controlling patients aimed to gain command of the situation and sought information, advice, and opinions (37,39–41). Emotion-controllers instead focused on how to handle the negative emotions associated with the situation (38). These emotions ranged from "shock" (42,44), to "anger" (36), "fear" (42,44), and "torture" (44). They used a variety of methods to minimize emotions, including false hope (42), avoidance (38,42), dependence on others to make decisions, and passive acceptance of treatment (33).

Commencing or Withholding Dialysis: Health Care Professional Factors.

Biomedical Criteria

The health care professionals’ decision on whether to start dialysis was predominantly influenced by medical criteria and clinical experience (34) rather than patient preference. Patients perceived that maintenance of "physiologic balance" was the health care professional’s aim (33). The medical criteria weighed by physicians were primarily age, comorbidities, physical function, prognosis, and cognitive impairment (34,35). Because of the unpredictable and asymptomatic nature of disease progression, blood tests were often relied upon to predict and educate patients about when dialysis may be required (42); however, patients often "lacked understanding of the blood test value’s meaning relative to their own experience" (42).

Ethical Dilemma

Physicians also recognized when it was unethical to prolong life, particularly with frail patients and those with a terminal illness (34). They acknowledged that dialysis could prolong "the suffering and the process of dying, rather than adding quality days to the patient’s life" (34). Nonetheless, even when health care professionals did not think someone would benefit from dialysis, they continued to offer the treatment because to withhold treatment was difficult (34) and they were led by their instinct to "err on the side of life" (34).

Commencing or Withholding Dialysis: Patient and Health Care Team Interaction.

Power and Communication

An important barrier to shared decision-making was the perceived power and dominance of the health care team. Health care professionals were considered to own the knowledge "and decided what the patient needed to know" (33,42); the patient relied on the team to share any knowledge (33). Health care professionals, however, also described their own "sense of powerlessness" (42) when faced with patients with ESRD, given the inevitability of disease progression.

Lelie found that physicians had typical "ideal" ways to provide information to patients of different age groups (35), with younger patients less likely to be informed of the option of conservative kidney management. Some patients were satisfied with the information they received (33) and thought they had made an informed independent decision (36,37). Others felt uninformed, did not feel they could ask questions, or did not know what to ask (33,42). Moreover, some misunderstood the information (36) and in particular its potential effect on their lives (42).

Acutely unwell patients often had little time to make a decision, could not always remember what had happened (33), or were unable to "deliberate" about treatment (39). The information provided was not consistent and was considered as "accidental" in its delivery (33). These patients often did not consider the decision to be their own (39).

The way information, and, in particular, risk, was presented influenced patient’s decisions (36,40,43). Some patients, after discussion with health care professionals, did not think a decision needed to be made (36). When health care professionals did communicate the uncertainty around the choice of treatment, this resulted in fear (40); however, more information about the future was still considered better than none by patients (42).

In addition, the person who provided the information and whether they were trusted by the patient was important (33,36,40,43). The majority felt that "if you wanna live" (40), you had to trust the physician to offer treatments that provided future hope (40). The decision was unique and complex, and so "who else you gonna trust" (40) was expressed to justify a dependence on professional judgement, which commonly nudged patients toward the choice considered to be medically optimal (39).

Dialysis Withdrawal: Patient-Level Factors.

Life on Dialysis

Participants remained convinced of their choice to have dialysis while they continued to experience the symptomatic benefits of treatment (40). At this stage dialysis had made them feel better, and this furthered their trust in the health care team (33). However, once their condition was no longer improving, past choice was questioned (40,42). This was typically after a prolonged period (e.g., years) on dialysis, when the "arduous" realities of life on dialysis were more fully appreciated (36,40–44). For many, particularly emotion-controlled patients, "their passive acceptance later generates profound questions about the meaning and worth" (39) of life on dialysis. This resulted once again in a feeling of powerlessness about one’s own life and a weariness (41), described as "sick of coming here," "had enough," and "just don’t want to do this anymore" (41).

Facing Withdrawal

Over time, participants reported that dialysis came to be seen as a "death sentence" in itself (44). Unfortunately, by this stage patients were dependent on treatment and withdrawal would result in imminent death, often within days (45). Therefore, the anxiety around such a decision was heightened, especially for those who had avoided the decision to commence dialysis in order to control their emotions (34,44) and were now faced with the same difficult choice between life on dialysis or death, but with more acute consequences if they chose the latter (34).

As with the decision to withhold treatment, individuals coped with dialysis withdrawal in a problem-controlling or emotion-controlling way. For some problem-focused patients, it was important to know they could stop treatment because this gave them back control (41). In contrast, the emotion controllers did not want to face such a decision and so focused on the present to avoid thoughts about future uncertainties (42).

Family Influence

From the family’s perspective the decision to withdraw treatment was equally difficult. Families found it difficult to differentiate between "allowing death and choosing it" (41), and so "guilt" (41) was closely associated with such decisions.

Dialysis Withdrawal: Health Care Professional Factors.

Avoidance

Despite the worries expressed by patients on dialysis, health care professionals acknowledged their own concerns about initiating discussions about treatment withdrawal (34,39,42). This was because they did not want to upset patients by being "too explicit" (41), the uncertainty of disease progression (42), and the moral and ethical burdens associated with such decisions (43). There was also evidence that over an extended period a close relationship develops between patients and the renal team (41). This made it difficult for health care professionals to separate their own instinct from the patient’s choice (41).

Genuine Request

Health care professionals also found it difficult to distinguish between a genuine request for withdrawal, from an attempt to simply discuss the goals of therapy and complain given the demanding nature of dialysis (39,41). This resulted in cautious interpretation of patient cues to discuss withdrawal, with depression and other treatable causes considered at first (41). Whether patients fully understood the implications of treatment withdrawal was also a concern (41).

Dialysis Withdrawal: Patient and Health Care Team Interaction.

Doing Trumps Talking

Patients "missed engaging in the dialogue" (33), which was once easily accessible, "rote" (41), and "procedural" (41) during predialysis education. The task-orientated conduct of the dialysis team made patients feel "controlled and incapacitated" (33). Health care professionals, however, considered patients as "voting with their feet," with "doing" considered to "trump talking" (41). These individuals attended dialysis week after week, and the team interpreted this as evidence of ongoing consent to treatment. Lack of acknowledgment that under the "veneer of straightforward participation in the treatment, are doubt and ambivalence" (41) was thought to result from the team’s presumption that patients must want to choose life and therefore continued to attend dialysis (34,41).

If Not Now, When?

Even when health care professionals judged that treatment was futile and patients continued to deteriorate despite dialysis, withholding treatment was frequently delayed until it became physiologically necessary (34,40). From both the patient’s and health care professional’s perspective, the point of withdrawal remained in the future, once all alternatives had been exhausted (41).

Discussion

Decision-making in ESRD is complex and dynamic and evolves over time and toward death. The factors at work operate differently for patients and health care professionals. Our findings resonate with results from previous quantitative and qualitative studies, but this synthesis expands on these and provides a deeper understanding of how and why different factors influence decisions about dialysis.

To facilitate informed shared decision-making, it is important to incorporate decision-making theory into tools designed to make such processes explicit to stakeholders, such as the RPA clinical practice guidance on shared decision-making (6). We found that patients made their choice through careful deliberation of multiple factors, as well as their gut instinct. This is consistent with dual processing theory, which proposes there are two modes of thinking: system 1, which is intuitive (i.e., based on gut instinct), and system 2, which is analytical (i.e., involving the deliberation of factors) (46–48). System 2 requires high cognitive effort and is often used when decision accuracy is pertinent (49), such as in ESRD. System 1 requires less cognitive effort (49); therefore, patients with cognitive impairment secondary to uremia or comorbidities may rely on this. Health care professionals also used system 1 and 2 processing. They relied predominantly on the deliberation of biomedical and ethical factors but were also driven by an instinct to "err on the side of life" (34). Making such cognitive processes transparent to patients, family members, and health care professionals, through the shared decision-making process advocated by the RPA guidance (6), is necessary to ensure decisions are informed and consistent with the patient’s preference.

How patients coped with emotions was also important. The effect of emotions on choice is well described, and it is suggested that an emotional reaction to a stimulus is the most important factor to guide decisions (50). Two coping mechanisms, problem controlling and emotion controlling, were evident. These are consistent with Folkman and Lazarus’s (51) theory of problem- and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused individuals deal with unpleasant emotions and situations by attempting to solve the underlying problem, whereas emotion-focused individuals cope by minimizing thoughts and feelings about the problem (51). Health care professionals also found decision-making a challenge, as patients gradually progressed along an unpredictable trajectory toward death. Current guidance on shared decision-making does not address support for health care professionals (6). Acknowledgment and regular assessment and support for the emotional effect of decision-making in this context are therefore required; how to provide and implement this requires further research.

The synthesis also highlighted how factors that affect choice for patients and health care professionals evolve over time, and in particular how predialysis education did not prepare patients sufficiently for their personal experience of life on dialysis. In view of this and the difficulties in initiating discussions about treatment withdrawal, one recommendation is to extend the role of predialysis nurses to continue throughout the disease trajectory. This will provide continuity in discussions about treatment with a designated individual, who has already invested time to understand the patient’s priorities, and will therefore enable the RPA guidance to be applied in a sensitive and timely manner.

Most studies in this review were from Western, developed countries (n=11) and did not commonly report patients' ethnicity, level of education, or the socioeconomic class. Few studies provided information on those who chose conservative management. Patients with cognitive impairment were not included in the original studies. In addition, the experiences of those waiting for renal transplants were not within the scope of this review. These areas require further research.

The nephrology community has made substantial advances to address the issue of advance care planning in ESRD. To ensure such decisions are shared and informed, system 1 and 2 information processing, as well as how individuals cope with the decision-making process, must be further understood and incorporated into decision-making tools. Furthermore, continuity of patient-centered communication throughout the disease trajectory may facilitate timelier joint decision making with regard to dialysis withdrawal.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was undertaken as part of a Masters by thesis funded through an National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Fellowship. The authors are grateful to Professor Karl Atkin and Dr. Peter Knapp for their advice and comments as members of the Thesis Advisory Panel and Dr. Matthew Nielson for screening studies.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11091114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, Arnold RM, Bridgman JC, Ward SE: Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2815–2823, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fresenius Medical Care: ESRD Patients in 2011: A Global Perspective, Bad Homburg, Germany, Fresenius Medical Care, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L: Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med 27: 829–839, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1608–1614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renal Physicians Association Working Group: Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis: Clinical practice guideline. Renal Physicians Association. 2010. Available at: http://www.renalmd.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=2710 Accessed January 2015

- 7.Ahmed S, Addicott C, Qureshi M, Pendleton N, Clague JE, Horan MA: Opinions of elderly people on treatment for end-stage renal disease. Gerontology 45: 156–159, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajwa K, Szabo E, Kjellstrand CM: A prospective study of risk factors and decision making in discontinuation of dialysis. Arch Intern Med 156: 2571–2577, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davison SN, Jhangri GS: The impact of chronic pain on depression, sleep, and the desire to withdraw from dialysis in hemodialysis patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 30: 465–473, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tse DMW: Experience of a renal palliative care program in a Hong Kong center: Characteristics of patients who prefer palliative care to dialysis. Hong Kong J Nephrol 11: 50–58, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bapat U, Nayak SG, Kedleya PG, Gokulnath : Demographics and social factors associated with acceptance of treatment in patients with chronic kidney disease. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 19: 132–136, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, Nguyen AT, Touam M, Grünfeld JP, Jungers P: Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: Cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1012–1021, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navaneethan SD, Kandula P, Jeevanantham V, Nally JV, Jr, Liebman SE: Referral patterns of primary care physicians for chronic kidney disease in general population and geriatric patients. Clin Nephrol 73: 260–267, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekkarie MA, Moss AH: Withholding and withdrawing dialysis: The role of physician specialty and education and patient functional status. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 464–472, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen LM, Germain M, Woods A, Gilman ED, McCue JD: Patient attitudes and psychological considerations in dialysis discontinuation. Psychosomatics 34: 395–401, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hines SC, Badzek L, Moss AH: Informed consent among chronically ill elderly: Assessing its (in)adequacy and predictors. J Appl Commun Res 25: 151–169, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morton RL, Howard K, Webster AC, Snelling P: Patient INformation about Options for Treatment (PINOT): A prospective national study of information given to incident CKD stage 5 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1266–1274, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenzie JK, Moss AH, Feest TG, Stocking CB, Siegler M: Dialysis decision making in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 12–18, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch DJ: Death from dialysis termination. Nephrol Dial Transplant 4: 41–44, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leggat JE, Jr, Bloembergen WE, Levine G, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Port FK: An analysis of risk factors for withdrawal from dialysis before death. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1755–1763, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orsino A, Cameron JI, Seidl M, Mendelssohn D, Stewart DE: Medical decision-making and information needs in end-stage renal disease patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 25: 324–331, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parry RG, Crowe A, Stevens JM, Mason JC, Roderick P: Referral of elderly patients with severe renal failure: Questionnaire survey of physicians. BMJ 313: 466, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powers BA: Generating evidence through qualitative research. In: Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Health Care, edited by Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC: The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 340: c112, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray MA, Brunier G, Chung JO, Craig LA, Mills C, Thomas A, Stacey D: A systematic review of factors influencing decision-making in adults living with chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ Couns 76: 149–158, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Health: The National Service Framework for Renal Services. Part Two: Chronic Kidney Disease, Acute Renal Failure and End of Life Care. 2005. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/199002/National_Service_Framework_for_Renal_Services_Part_Two_-_Chronic_Kidney_Disease__Acute_Renal_Failure_and_End_of_Life_Care.pdf. Accessed January 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flemming K: The synthesis of qualitative research and evidence-based nursing. Evid Based Nurs 10: 68–71, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flemming K, Briggs M: Electronic searching to locate qualitative research: Evaluation of three strategies. J Adv Nurs 57: 95–100, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J: Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 12: 1284–1299, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3: 77–101, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robson C: Real World Research, 2nd Ed., Oxford, United Kingdom, Blackwell, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J: Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 12: 181, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aasen EM, Kvangarsnes M, Heggen K: Perceptions of patient participation amongst elderly patients with end-stage renal disease in a dialysis unit. Scand J Caring Sci 26: 61–69, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halvorsen K, Slettebø A, Nortvedt P, Pedersen R, Kirkevold M, Nordhaug M, Brinchmann BS: Priority dilemmas in dialysis: The impact of old age. J Med Ethics 34: 585–589, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lelie A: Decision-making in nephrology: Shared decision making? Patient Educ Couns 39: 81–89, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noble H, Meyer J, Bridges J, Kelly D,Johnson B: Reasons renal patients give for deciding not to dialyze: A prospective qualitative interview study. Dial Transplant 38: 82–89, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tweed AE, Ceaser K: Renal replacement therapy choices for pre-dialysis renal patients. Br J Nurs 14: 659–664, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breckenridge DM: Patients’ perceptions of why, how, and by whom dialysis treatment modality was chosen. ANNA J 24: 313–319, discussion 320–321, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaufman SR, Shim JK, Russ AJ: Old age, life extension, and the character of medical choice. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 61: S175–S184, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly-Powell ML: Personalizing choices: Patients’ experiences with making treatment decisions. Res Nurs Health 20: 219–227, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russ AJ, Shim JK, Kaufman SR: The value of “life at any cost”: Talk about stopping kidney dialysis. Soc Sci Med 64: 2236–2247, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA: Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: A qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 495–503, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashby M, op’t Hoog C, Kellehear A, Kerr PG, Brooks D, Nicholls K, Forrest M: Renal dialysis abatement: Lessons from a social study. Palliat Med 19: 389–396, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin CC, Lee BO, Hicks FD: The phenomenology of deciding about hemodialysis among Taiwanese. West J Nurs Res 27: 915–929, discussion 930–934, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murtagh F, Cohen LM, Germain MJ: Dialysis discontinuation: Quo vadis? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 379–401, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahneman D, Frederick S: Representativeness revisited: attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In: Heurisitics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement, edited by Gilovich T, Griffin D, Kahneman D, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp 49–81 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sloman SA: The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychol Bull 119: 3–22, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stanovich KE, West RF: Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? In: Heurisitics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement, edited by Gilovich T, Griffin DW, Kahneman D, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp 421–440 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kahneman D: A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality. Am Psychol 58: 697–720, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zajonc RB: Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. Am Psychol 35: 151–175, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Folkman S, Lazarus RS: Coping as a mediator of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol 54: 466–475, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.