Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this systematic review was to review clinical studies of fixed tooth-supported prostheses, and to assess the quality of evidence with an emphasis on the assessment of the reporting of outcome measurements. Multiple hypotheses were generated to compare the effect of study type on different outcome modifiers and to compare the quality of publications before and after January 2005.

Materials and Methods

An electronic search was conducted using specific databases (MEDLINE via Ovid, EMBASE via Ovid, Cochrane Library) through July 2012. This was complemented by hand searching the past 10 years of issues of the Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, Journal of Prosthodontics, and the International Journal of Prosthodontics. All experimental and observational clinical studies evaluating survival, success, failure, and complications of tooth-supported extracoronal fixed partial dentures, crowns, and onlays were included. No restrictions on age or follow-up time were placed.

Results

The electronic search generated 14,869 papers, of which 206 papers were included for full-text review. Hand-searching added 23 papers. Inclusion criteria were met by 182 papers and were included for the review. The majority were retrospective studies. Only 8 (4.4%) were randomized controlled trials. The majority of the studies measured survival and failure, and few studies recorded data on success; however, more than 60% of the studies failed to define survival, success, and failure. Many studies did not use any standardized criteria for assessment of the quality of the restorations and, when standardized criteria were used, they were modified, thereby not allowing for comparisons with other studies. There was an increase of 21.8% in the number of studies evaluating outcome measurements of all-ceramic restorations in past 8 years.

Conclusions

Prosthodontic literature presents with a reduced percentage of RCTs compared to other disciplines in dentistry. The overall quality of recording prosthodontic outcome measurements has not improved greatly in the past 8 years.

Keywords: Success, survival, treatment failure, complications, standardized criteria, treatment outcome, evidence-based dentistry

Clinicians are confronted daily with treatment dilemmas for their patients. Ideally, informed treatment decisions should be based on sound scientific evidence, combined with patient desires and clinical experience.1 Therefore, it is important that clinicians recognize good-quality evidence and only use such studies in support of their daily practice. Treatment outcome measurements are a key factor in evaluating various treatment modalities. These are often expressed in published studies with various terms such as “survival,” “success,” “failure,” and “complications.” Studies assessing various outcome measurements should be conducted using standardized methods, and all important aspects of the studies should be reported clearly to maintain transparency and reduce the risk of bias.2,3 Therefore, the quality of study design and reporting of results are very important aspects when the literature is used to compare treatment modalities and prioritize treatment options. These factors have been recognized by both medical and dental researchers, and the quality of published studies of various disciplines has been assessed in both fields.4–13

Numerous papers have evaluated fixed prosthodontic treatment outcomes; however, the definitions of success and survival, and the criteria used to evaluate the data differ greatly among different studies. These variations in definitions hinder the interpretation and reliable combination of data over several studies and may preclude any meaningful direct comparisons of fixed prosthodontic treatment outcomes.2,11,14,15 Pjetursson et al16 considered a fixed partial denture (FPD) to be successful if it remained unchanged and free from all complications over the entire observation period. An FPD was considered to have survived if it remained in situ with or without modification over the observation period. The most objective category of failure is the removal of the FPD; however, this definition of failure clearly overstates the success of FPDs, as many are found in situ but in need of replacement.17 A recent systematic review18 of the literature identified such issues in a large number of implant-related studies. Most studies were unclear regarding the nature of the study groups and failed to clearly define “survival” and “success;” the terms were often used interchangeably. Torabinejad et al11 observed that methods for calculating outcomes were not always reported in studies related to FPDs and complications were mostly not described. Lack of reporting quality in systematic reviews and RCTs has also been shown in studies evaluating various dental disciplines.9,10,13 A recent study12 showed a slight improvement in quality of reporting in implant dentistry over the past few years; however, most of the literature was still of low quality. Another study9 assessing the quality of reporting of systematic reviews in orthodontics compared reviews published between 1999 and 2004 and 2004 and 2009 and concluded there was no significant improvement in the quality of reporting.

Recommendations on reporting have been made for studies assessing longevity of restorations in order to standardize the measurement of outcomes.2 Clinical indices such as USPHS/Ryge criteria,19 CDA criteria,20 and Hickel's criteria21 have been developed, in an attempt to standardize the criteria for evaluating restorations. These criteria assess restoration qualities such as anatomic form, marginal integrity, caries, and color. According to the USPHS criteria19 all categories are given five scores: Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, and Oscar to determine if the restoration is in an excellent state or failing. In the CDA criteria20 satisfactory restorations are divided into “excellent” (A) and “acceptable” (B), and nonsatisfactory restorations are divided into “correct/replace” (C) and “replace” (D). Modifications of USPHS and CDA criteria have been used to include more categories for assessment. The proper use of such criteria has a direct effect on the reporting of outcome measurements. Moreover, forms have been developed for all-ceramic restorations to describe and classify details of chipping fractures and bulk fractures to satisfy criteria for comprehensive failure analyses and subsequent treatment planning.22 Nevertheless, some authors argue against using USPHS or CDA criteria because the degree of deviation from the ideal state is recorded on its own without considering other factors, and results may not be applied with validity to different clinical circumstances.3

There is no current comprehensive information available regarding the quality of study design, method of recording, and reporting of outcome measurements in studies evaluating tooth-supported fixed prostheses. The purpose of this systematic review was to review clinical studies of tooth-supported fixed prostheses, and assess study design, as well as the quality of recording and reporting of outcome measurements. Multiple hypotheses were generated to explore associations among various factors related to study design and different outcome modifiers and to compare the quality of the literature published prior to and after January 2005. This cut-off date was chosen arbitrarily, according to a similar article9 looking at the orthodontic literature.

Materials and Methods

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic search

Electronic literature searches of medical databases (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and RCTs [1980 to July 2012], EMBASE [1974 to July 2012], and MEDLINE [1948 to July 2012]), were carried out by one reviewer (DP) using specific search strategies, which included combination of MeSH terms and keywords: ((Crown$.mp. OR exp Crowns/ OR Onlay$.mp. OR Fixed partial denture.mp. OR exp Denture, Partial, Fixed/ Bridge$.mp.) AND (exp Prosthesis Failure/ OR exp Dental Restoration Failure/ OR exp Treatment failure/ OR Postoperative Complications/ OR Complication.mp. OR Success.mp OR Survival/ OR survival.mp. OR Longevity.mp. OR exp. Longevity OR Outcome adj3 Measur$)).

Searching other resources

Hand searching for relevant studies was performed by DP for the past 10 years of issues of the following journals: Journal of Oral Rehabilitation (JOR), Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry (JPD), Journal of Prosthodontics (JP), and International Journal of Prosthodontics (IJP).

Selection of studies

The selection process was conducted in two phases. During the first phase the titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (DP) according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Type of intervention

Clinical studies on humans, evaluating extracoronal tooth-supported restorations, specifically crowns, FPDs, and onlays were included, irrespective of material used. Studies exclusively related to implant-supported restorations, implant/tooth-supported or removable prostheses, post and core restorations, veneers and resin-retained FPDs, as well as studies evaluating intracoronal restorations were excluded.

Types of studies

Both observational studies (prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies, case control studies, and cross sectional studies) and experimental studies (randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials, noncontrolled clinical trials, and case-series) were included for the review. Studies involving questionnaires and interviews, clinical reports, and expert opinion papers were excluded. Only studies published in English were included.

Follow-up time

As the identification of outcome measurements was one of the primary goals of this study, all studies were considered for inclusion irrespective of their follow-up time.

Types of outcome measurements

Clinical studies evaluating quantitative outcome measurements such as success, survival, failure and/or complications were considered for inclusion. If a study included both relevant and irrelevant data, for example, implant- and tooth-supported restorations, it was included, but only the relevant data was used towards the final review.

Another reviewer (TOB) independently screened the results. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between three reviewers (DP, HP and TOB) and in cases where there was any doubt, the full text of the paper was obtained. The full text of all the papers that passed the first review phase was finally retrieved. Full-text papers generated from hand searching were added after discussion for any disagreement. The second phase of the review included all full-text papers, which were assessed by two reviewers (DP and TOB) for inclusion or exclusion by applying the criteria set previously. A specific data collection form was constructed, and a pilot run was performed. Any disagreements between DP and TOB were resolved via discussion and refereeing by HP. Data collection of all included papers was done by one reviewer (DP). Regarding data collection, inter-reviewer agreement between TOB and DP was calculated by assessing 10% of the papers. DP further reviewed 10% of the papers, again, for intrareviewer agreement calculation to be performed. Inter-reviewer and intra-reviewer agreement were determined using Cohen's kappa (κ) coefficients.23

Data collection and analysis

Once the final number of included studies was agreed upon by three of the authors (DP, HP and TOB), data were collected using the custom data collection form and set guidelines for each of the following four categories: demographic data, clinical data, study design, and outcome measurements recording and reporting.

Statistical analyses of hypotheses

Multiple hypotheses were generated to explore associations among various factors related to study design and different outcome modifiers and to compare the quality of literature published between two time periods: from 1948 to December 2004 (group 1) and from January 2005 to July 2012 (group 2). Once all the data were collected, frequencies and percentages were analyzed and compared by the Pearson's Chi-Square test using statistical software SPSS v 17.0 for windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The level of significance was set at 0.01 rather than the conventional 0.05 to avoid spuriously significant results arising from multiple testing.

Results

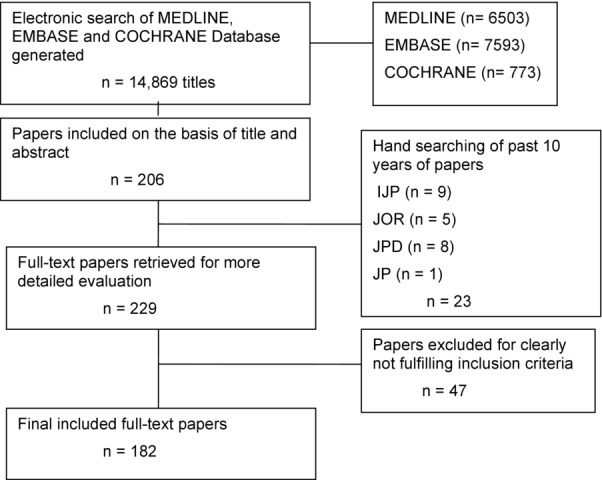

The study selection flow chart is illustrated in Figure 1. The electronic database search generated 14,869 papers. After title and abstract reviewing, 206 papers were included for full-text retrieval. Journal hand searching produced 23 more full-text papers. Phase 2 review of the full texts led to the exclusion of 47 additional studies (reasons for exclusion are depicted in Table 1), resulting in 182 papers included for the final analysis. Included studies are listed in the Appendix. There was good inter-reviewer (inclusion/exclusion κ = 0.91; data extraction κ = 0.82) and intra-reviewer agreement (κ = 0.95) during all selection phases.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of results generated by search strategy and final result after application of inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Number of excluded studies during phase 2, and reasons for exclusion

| Details of excluded studies | |

|---|---|

| Reason for exclusion | Number of studies |

| Same cohort used in different studies | 12 |

| No success, survival, failures, or | 12 |

| complications measured | |

| Resin-retained FPD, intracoronal restorations | 10 |

| Clinical reports | 4 |

| Descriptive study, literature review | 7 |

| In vitro study | 2 |

Demographic data

Results showed that all studies had recorded information on the final number of patients. However, age range and mean age of the patients were not recorded by 31.3% and 40.7% of studies, respectively.

Clinical data

The majority of studies (85.7%) reported some information on tooth descriptors, mostly the position of the tooth in the mouth (76.9%); however, less than half of those studies reported the periodontal (38.5%) or endodontic status (41.8%) of the teeth. Very few studies (8.2%) reported on the amount of remaining tooth structure prior to restoration placement.

The majority of included studies (65.4%) did not provide any information on certain patient characteristics, such as the type of occlusion or the presence of parafunction. The reasons for restoration placement were usually not (85.7%) provided.

The most frequent restorations studied were full-coverage crowns (34.6%) and FPDs (60.9%). In most included studies (72%) the type of luting agent was described, and in almost half (51.6%) the tooth preparation and finish was explained. The most commonly evaluated restoration materials were all-ceramic (58.8%), followed by metal-ceramic (29.7%). Most of the included studies had been conducted in a university setting (57.1%), whereas 27.5% had used private practice settings.

Study design

Most of the included studies were observational (57.7%), and only 4.4% were RCTs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency (percentage) of types of studies included for review

| Type of study | |

|---|---|

| Study type | Frequency (%) |

| Observational study | 105 (57.7%) |

| Retrospective cohort study | 99 (54.4%) |

| Prospective cohort study | 6 (3.3%) |

| Experimental study | 77 (42.3%) |

| RCT | 8 (4.4%) |

| Controlled clinical trial (non-randomized) | 3 (1.6%) |

| Clinical trials (uncontrolled, non-randomized) | 66 (36.3%) |

| Total | 182 (100.0%) |

Outcome measurements recording and reporting

Survival, success, and failure

Survival was measured in 135 studies; however, only 23 defined the term “survival.” Success was measured in 65 studies, but only 26 defined the criteria for “success.” Failure was measured in 152 studies, and only 54 defined the term ‘’failure’’ (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of studies recording data on survival, success, and failure

| Data on survival, success, and failure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Yes frequency (%) | No frequency (%) | Total frequency (%) |

| Survival measured | 135 (74.2%) | 47 (25.8%) | 182 (100%) |

| Survival defined | 23 (17.0%) | 112 (83.0%) | 135 (100%) |

| Success measured | 65 (35.7%) | 117 (64.3%) | 182 (100%) |

| Success defined | 26 (40.0%) | 39 (60.0%) | 65 (100%) |

| Failure measured | 152 (83.5%) | 30 (16.05%) | 182 (100%) |

| Failure defined | 54 (35.5%) | 98 (64.5%) | 152 (100%) |

Various definitions of “survival” were provided, such as:

“Restored tooth remained intact, fixed prosthesis remaining intact, restored tooth remaining free from radiographic and clinical signs and symptoms of pulp deterioration.”24

“The period of time starting at the cementation of the restoration and ending when the crown was shown to have irreparably failed, for example, Porcelain fracture or partial debonding that exposed the tooth structure and impaired aesthetic quality.”25

“Crown not removed.’’26

Similar variation could be found in the definition of “success” among the included studies:

“Those crowns that were present without core fracture, porcelain fracture, caries, sign of periodontal inflammation (specifically bleeding on probing), or endodontic sign and symptoms.”27

“Restorations still in clinical service.” 28

“No framework fracture of zirconia.”29

Various definitions of “failure” were:

Types of methods used for survival, success, and failure analyses

It was disturbing to find that more than a third of included studies (37.7%) had not described the method of statistical analysis of survival data. Among the studies that did report the statistical methods, Kaplan-Meier analysis was the most popular (55.4%).

Complications

The majority (94.5%) of included studies reported data encompassing a wide range of biological, mechanical, and esthetic prosthesis complications (Table 4). Other types of complications including sensitivity, mobility, overcontoured crown, temporomandibular dysfunction, dislodgement of the post, etc. were recorded by 44.8% of the studies.

Table 4.

Frequency of studies recording data on various types of complications

| Complication type | Frequency (%) | Complication type | Frequency (%) | Complication type | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | 157 (91.3%) | Mechanical | 168 (97.7%) | Esthetic | 108 (62.8%) | Other complications |

| Pain | 28 (16.3%) | Porcelain fracture | 153 (89.0%) | Poor esthetics | 106 (61.6%) | 77 (44.8%) |

| Caries | 136 (79.1%) | Fractured tooth/root | 98 (57.0%) | Recession | 12 (7.0%) | |

| Periapical pathology | 115 (66.9%) | Fractured prostheses | 149 (86.6%) | |||

| Periodontal disease | 100 (58.1%) | Loss of retention | 97 (56.4%) | |||

| Effect on opposing tooth | 11 (6.4%) | Defective margins | 105 (61.0%) |

Standardized criteria

More than half of the studies did not use any standardized criteria for prosthesis evaluation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of criteria used to assess the quality of restorations

| Standardized criteria | |

|---|---|

| Criteria used | Frequency (%) |

| CDA Criteria | 31 (17%) |

| Modified CDA Criteria | 12 (6.6%) |

| USPHS Criteria | 6 (3.3%) |

| Modified USPHS Criteria | 31 (17%) |

| Other | 6 (3.3%) |

| None | 96 (52.8%) |

| Total | 182 (100.0%) |

Results of the hypotheses testing

Detailed results from hypotheses testing are provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of null hypotheses testing

| Results of null hypotheses testing (significance level p < 0.01) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Null hypotheses | p Value | Observational study (n/total) | Experimental study (n/total) |

| Study design is not associated with the fact that success, survival, and failures were well defined | 0.956 (Survival) | 13/77 | 10/58 |

| 0.415 (Success) | 16/36 | 10/29 | |

| 0.006 (Failure) | 40/90 | 14/62 | |

| Study design is not associated with the lack of use of analytical methods for assessment of survival, success, and failure | 0.583 | 36/105 | 29/77 |

| Study design is not associated with the type of setting used (private practice vs university) | 0.213 | 34 (Private) & 64 (University) /98 | 16 (Private) & 47 (University) /63 |

| Study design is not associated with the patient descriptors | 0.003 | 78/105 | 41/77 |

| Study design is not associated with the tooth descriptor | <0.001 | 23/105 | 3/77 |

| Study design is not associated with the description of tooth preparation included in the paper | <0.001 | 28/105 | 61/77 |

| Study design is not associated with the type of material used | <0.001 (all-ceramic) | 42/105 | 65/77 |

| <0.001(PFM) | 44/105 | 10/77 | |

| Study design is not associated with the use of the standardized criteria to assess restoration | <0.001 | 32 /105 | 54 /77 |

| Group 1(n)/ Total | Group 2(n)/ Total | ||

| The proportions of recording definitions for fixed prosthodontic outcomes (i.e., survival, success, and failure) is the same for groups 1* and 2** | 0.267 (Survival) | 6/48 | 15/74 |

| 0.156 (Success) | 10/32 | 16/33 | |

| 0.339 (Failure) | 24/76 | 30/77 | |

| The proportions of reporting of methods used to analyze outcomes is the same for groups 1 and 2 | <0.001 | 44/83 | 21/91 |

| The proportions of type of setting used is the same for groups 1 and 2 (private practice vs. university) | 0.020 | 49/81 | 62/80 |

| The proportions of reporting patient descriptors is the same for groups 1 and 2 | 0.326 | 62 /90 | 57 /92 |

| The proportions of reporting tooth descriptors is the same for groups 1 and 2 | 0.002 | 20/90 | 6/92 |

| The proportions of reporting detailed tooth preparation is the same for groups 1 and 2 | 0.005 | 37/90 | 57/92 |

| The proportions of using different types of restorative materials is the same for groups 1 and 2 | 0.003 (all-ceramic) | 43/90 | 64/92 |

| 0.923 (PFM) | 27/90 | 27/92 | |

| The proportions of reporting the use of standardized criteria is the same for groups 1 and 2 | 0.453 | 40/90 | 46/92 |

| The proportions of experimental studies and observational studies measuring fixed prosthodontics outcomes is the same for groups 1 and 2 | 0.128 | 33 (experimental) & 57 (observational)/90 | 44 (experimental) & 48 (observational) /92 |

Group 1 (Literature published up to the end of December 2004).

Group 2 (Literature published from January 2005 until July 2012).

Relation between study design and important factors related to outcome measurements

There was a significant effect (p < 0.01) of study design, that is, observational or experimental, on type of material used, use of standardized criteria to evaluate restorations, description of tooth preparation and lack of information on patients and tooth descriptors. Observational studies evaluated more metal-ceramic restorations than all-ceramic restorations. This category also used standardized criteria less frequently, and there was a lack of detailed record of tooth preparation and patient and tooth descriptors, whereas experimental studies performed significantly better in those areas. Observational studies recorded definition of failure significantly more frequently than experimental studies; however, there was no statistically significant effect (p > 0.01) of study design and frequency of recording data on the definition of survival and success or on the type of settings used.

Comparison between studies published until December 2004 (group 1) and from January 2005 till July 2012 (group 2)

Group 1 consisted of 90 papers, and group 2 consisted of 92 papers. Generally papers included in group 2 recorded relevant information more frequently than papers included in group 1; however, the difference was not statistically significant in most categories.

Statistically significant (p < 0.01) differences were found for the following issues (Table 6)

In group 1, 22.2% of the papers did not record any type of tooth descriptor, but an improvement was seen in group 2 studies where only 6.5% failed to record any type of tooth descriptor. More studies in group 2 described type of tooth preparation undertaken and luting cement used than in group 1. Group 2 recorded detailed tooth preparations significantly more frequently than group 1. An increase of more than 20% in the papers evaluating all-ceramic crowns was noted in group 2 studies. In group 2, 10.9% of the studies failed to record the type of setting used, whereas only 4.4% of the studies failed to record this information in group 1. Group 1 described the method of analysis used to assess survival, success, and failure significantly less frequently then group 2.

Discussion

There is a lack of data available on the quality of recording and reporting outcome measurements in tooth-supported fixed prostheses. Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence showing any improvements in reporting outcome measurements of fixed prostheses in recent years. The purpose of this systematic review was to review clinical studies of tooth-supported fixed prostheses, and assess study design as well as the quality of recording and reporting of outcome measurements. A broad literature search was conducted to avoid missing any important papers. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were clearly defined and peer-reviewed to help generate the required papers for assessment.

The results of this systematic review showed that some baseline information, such as the reason for restoration of the tooth, and patient descriptors including bruxism, was not always recorded accurately. This finding is in agreement with a previous study13 that looked at the quality of reporting of RCTs in prosthodontics, a study2 published on direct restorations, and a recent review18 of outcome measures in implant literature. Bruxism has been associated with porcelain chipping and increased frequency of complications;33 therefore, the lack of reporting of this and other prognostic factors or patient characteristics as confounding variables may significantly affect the results.

The results of this study also showed there has been no significant increase in the percentage of RCTs in published studies pertaining to tooth-supported fixed restorations through the years. This is in contrast to literature that has evaluated the percentage of published RCTs in implant18 and dental7 literature.

The primary outcomes evaluated in this review were survival, success, failures, and complications. To maintain transparency and comparability, it is crucial to record the details of measured outcomes with criteria against which they were assessed. Generally survival of restorations relates to the restorations being in situ irrespective of their condition, whereas usually criteria measuring success are stricter. Hence, it is impossible to compare studies measuring success with studies measuring survival. It is also not feasible to compare two studies measuring success of the same type of restorations if the definition of success is different. A variety of definitions of similar outcomes, that is, survival, success, or failure, were used, and not all authors adhered to the same strict criteria in the included studies. This finding has been reported by other studies as well.14,18 Reduced numbers of definitions confirms the lack of standardization of the measurements and design between studies.11 Use of standardized definitions of survival, success, and failure is also recommended.

While calculating the survival time of a particular restoration, some difficulty may occur due to patients being lost to follow-up or due to the study terminating prior to the patients experiencing the outcome event. This phenomenon is known as censoring. If censoring is not taken into account, then survival data may underestimate the true time to event analysis, and hence special methods are needed to evaluate survival, and standard methods of data exploration may not be useful.34 The results of this study showed that 38.9% of the studies did not record the type of method used to evaluate the survival data. This finding is in agreement with another recent study35 and has also been reported in a review18 of implant literature.

Understanding relevant complications related to fixed prosthodontics can improve the clinician's ability to perform accurate diagnosis, construct an appropriate treatment plan, set realistic expectations for the patients, and plan postoperative care. Using set criteria for evaluating the quality of restorations can produce more consistent and comparable results for particular outcome measurements. The results of this study showed that the evaluation process of quality of restorations still a lacks standardization, since half the studies did not use any standardized indices to evaluate the quality of restorations. Some studies assessed occlusion and the level of interference along with other factors using USPHS criteria.36 One study assessed only marginal quality, contour, surface texture, and color match,37 whereas another assessed postoperative sensitivity, recurrent caries, marginal adaptation, proximal contact, anatomic form, and surface texture.38 Both of these studies used USPHS criteria but modified them differently. Many studies used modified USPHS criteria; however, there was lack of standardization among assessment procedures, which is in agreement with other studies.2,3

Multiple hypotheses were generated to assess the relationship between study design and different factors, such as methods of reporting, definitions, and assessment criteria. Fundamentally, observational studies, especially retrospective cohort studies, are different than experimental studies and limited by the type of data recorded at the time of initial examination, at the time of treatment, and on the last examination in order to assess the restoration. This review identified most of the studies as retrospective, and various criteria had possibly not been defined at the time of the intervention. The analysis of the results of this study showed that the type of study had no significant influence on the frequency that the definition of survival and success was recorded, and no influence on the type of method used for outcome analysis; however, experimental studies generally recorded more information and were more standardized than observational studies. This result further emphasizes the need for and reflects the robustness of well-designed experimental studies.

In the past two decades evidence-based dentistry has become more popular, and various tools have been generated to assess the quality of reporting and, ultimately, to improve the quality of future studies.39,40 In this study, an attempt was made to compare various factors between studies published before (group 1) and after (group 2) the end of 2004. Evaluation of studies published between groups 1 and 2 showed an improvement in reporting of methods of analysis used; however, there was no significant improvement in defining success, survival, and failure or use of standardized criteria. This result meant that even in prospective trials, the quality of recording this information has not improved. Hence, better constructed prospective clinical trials are recommended for future research. The importance of blinded randomized controlled trials or adequately conducted prospective trials has been stressed in recent years to improve the quality of the studies.41 However, the results of this study showed no statistical difference between the proportions of experimental and observational studies published in recent years. This may suggest various limitations in conducting intervention studies for tooth-supported fixed restorations due to various reasons (e.g., ethical approval). This finding is not comparable to any other study. This systematic review was in agreement with other studies9,10,18 published in various other disciplines of dentistry, showing no significant improvement in the quality of published literature and overall quality of recording outcome measurements in recent years.

This study has limitations, such as the exclusion of non-English and grey literature, the fact that citations and references of included papers were not searched to find more articles, and that only 10% of the total papers were reevaluated at the data-collection stage; however, sensitive electronic and manual searches, coupled with the large number of final papers included, probably outweighed the above limitations. This was reflected by the satisfactory inter-reviewer and intra-reviewer agreement during the reevaluation phase after article search and collection.

Research papers on outcome measurements are very important for clinical day-to-day practice as they may provide clinicians with better understanding for making appropriate treatment decisions. They also provide appropriate and more accurate information in order to gain valid consent from the patients. The combination of the results of multiple research papers, such as in the form of meta-analyses, can provide very robust conclusions. The results of this systematic review showed a lack of standardization between studies evaluating similar outcomes, thus hindering the combination of data. Of particular concern is the lack of standardization regarding definitions of outcomes such as survival, success, and failure. The prosthodontic community should organize a consensus statement with precise definitions for the aforementioned terms which can be used by future studies. The same holds true regarding the standardizations of restoration evaluation criteria as has been previously suggested.2 The adherence of researchers to available guidelines such as CONSORT guidelines for RCTs42 and STROBE for observational studies43 will further enhance the quality and standardization of future published papers.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study the following conclusions could be drawn:

There has been no increase in published RCTs in prosthodontics during past decade compared to previous years.

A large proportion of the studies had problems with the definition, standardization, or with the reporting of methods used to calculate survival, success, and failure.

More than half of the studies did not use any standardized criteria for quality evaluation of the restorations.

The overall quality of recording prosthodontic outcome measurements has not improved greatly in past 8 years.

Appendix: Bibliography of Included studies

References

- 1.Arnelund CF, Johansson A, Ericson M, et al. Five-year evaluation of two resin-retained ceramic systems: a retrospective study in a general practice setting. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:302–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandlish LK, Mariatos G. Long-term survivals of ‘direct-wax’ cast gold onlays: a retrospective study in a general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2009;207:111–115. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes D, Gingell JC, George D, et al. Clinical evaluation of an all-ceramic restorative system: a 36-month clinical evaluation. Am J Dent. 2010;23:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bart I, Dobler B, Schmidlin K, et al. Complication and failure rates of tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses after 7 to 19 years in function. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:360–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beier US, Kapferer I, Dumfahrt H. Clinical long-term evaluation and failure characteristics of 1,335 all-ceramic restorations. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:70–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beier US, Kapferer I, Burtscher D, et al. Clinical performance of all-ceramic inlay and onlay restorations in posterior teeth. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentley C, Drake CW. Longevity of restorations in a dental school clinic. J Dent Educ. 1986;50:594–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg E, Nesse H, Skavland RJ, et al. Three-year split-mouth randomized clinical comparison between crowns fabricated in a titanium-zirconium and a gold-palladium alloy. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:312–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernhart J, Brauning A, Altenburger MJ, et al. Cerec3D endocrowns—two-year clinical examination of CAD/CAM crowns for restoring endodontically treated molars. Int J Comput Dent. 2010;13:141–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beuer F, Stimmelmayr M, Gernet W, et al. Prospective study of zirconia-based restorations: 3-year clinical results. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:631–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bindl A, Mormann WH. An up to 5-year clinical evaluation of posterior in-ceram CAD/CAM core crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15:451–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bindl A, Mormann WH. Survival rate of mono-ceramic and ceramic-core CAD/CAM-generated anterior crowns over 2-5 years. Eur J Oral Sci. 2004;112:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bindl A, Richter B, Mormann WH. Survival of ceramic computer-aided design/manufacturing crowns bonded to preparations with reduced macroretention geometry. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black SM, Charlton G. Survival of crowns and bridges related to luting cements. Rest Dent. 1990;6:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boeckler AF, Lee H, Stadler A, et al. Prospective observation of CAD/CAM titanium ceramic single crowns: a three-year follow up. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;102:290–297. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohlsen F, Kern M. Clinical outcome of glass-fiber-reinforced crowns and fixed partial dentures: a three-year retrospective study. Quintessence Int. 2003;34:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bragger U, Aeschlimann S, Burgin W, et al. Biological and technical complications and failures with fixed partial dentures (FPD) on implants and teeth after four to five years of function. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2001;12:26–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2001.012001026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bragger U, Hirt-Steiner S, Schnell N, et al. Complication and failure rates of fixed dental prostheses in patients treated for periodontal disease. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2011;22:70–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budtz-Jørgensen E, Isidor F. A 5-year longitudinal study of cantilevered fixed partial dentures compared with removable partial dentures in a geriatric population. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;64:42–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(90)90151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke FJT. Four year performance of dentine-bonded all-ceramic crowns. Br Dent J. 2007;202:269–273. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke FJT, Lucarotti PS. Ten-year outcome of crowns placed within the General Dental Services in England and Wales. J Dent. 2009;37:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke FJT, Qualtrough AJ, Wilson NH. A retrospective evaluation of a series of dentin-bonded ceramic crowns. Quintessence Int. 1998;29:103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson BR, Yontchev E. Long-term observations of extensive fixed partial dentures on mandibular canine teeth. J Oral Rehabil. 1996;23:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1996.tb01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cehreli MC, Kokat AM, Ozpay C, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of feldspathic versus glass-infiltrated alumina all-ceramic crowns: a 3-year follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2011;24:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chai J, Chu FC, Newsome PR, et al. Retrospective survival analysis of 3-unit fixed-fixed and 2-unit cantilevered fixed partial dentures. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:759–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung GSP, Dimmer A, Mellor R, et al. A clinical evaluation of conventional bridgework. J Oral Rehabil. 1990;17:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1990.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen RP, Ploeger BJ. A clinical comparison of zirconia, metal and alumina fixed-prosthesis frameworks veneered with layered or pressed ceramic: a three-year report. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:1317–1329. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coelho Santos MJM, Mondelli RF, Lauris JR, et al. Clinical evaluation of ceramic inlays and onlays fabricated with two systems: two-year clinical follow up. Oper Dent. 2004;29:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Backer H, Van Maele G, De Moor N, et al. Survival of complete crowns and periodontal health: 18-year retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:151–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Backer H, Van Maele G, De Moor N, et al. The influence of gender and age on fixed prosthetic restoration longevity: an up to 18- to 20-year follow-up in an undergraduate clinic. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Backer H, Van Maele G, De Moor N, et al. An up to 20-year retrospective study of 4-unit fixed dental prostheses for the replacement of 2 missing adjacent teeth. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:259–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Backer H, Van Maele G, De Moor N, et al. An 18-year retrospective survival study of full crowns with or without posts. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Backer H, Van Maele G, De Moor N, et al. A 20-year retrospective survival study of fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:143–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Backer H, VanMaele G, De Moor N, et al. Long-term results of short-span versus long-span fixed dental prostheses: an up to 20-year retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:75–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decock V, De Nayer K, De Boever JA, et al. 18-year longitudinal study of cantilevered fixed restorations. Int J Prosthodont. 1996;9:331–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eliasson A, Arnelund CF, Johansson A. A clinical evaluation of cobalt-chromium metal-ceramic fixed partial dentures and crowns: A three- to seven-year retrospective study. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98:6–16. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Encke BS, Heydecke G, Wolkewitz M, et al. Results of a prospective randomized controlled trial of posterior ZrSiO(4)-ceramic crowns. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:226–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esquivel-Upshaw JF, Anusavice KJ, Young H, et al. Clinical performance of a lithia disilicate-based core ceramic for three-unit posterior FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:469–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esquivel-Upshaw JF, Young H, Jones J, et al. Four-year clinical performance of a lithia disilicate-based core ceramic for posterior fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etemadi S, Smales RJ. Survival of resin-bonded porcelain veneer crowns placed with and without metal reinforcement. J Dent. 2006;34:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etman MK, Woolford MJ. Three-year clinical evaluation of two ceramic crown systems: a preliminary study. J Prosthet Dent. 2010;103:80–90. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fayyad MA, Al Rafee MA. Failure of dental bridges. II. Prevalence of failure and its relation to place of construction. J Oral Rehabil. 1996;23:438–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1996.tb00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Federlin M, Wagner J, Manner T, et al. Three-year clinical performance of cast gold vs ceramic partial crowns. Clin Oral Invest. 2007;11:345–352. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felden A, Schmalz G, Hiller KA. Retrospective clinical study and survival analysis on partial ceramic crowns: results up to 7 years. Clin Oral Invest. 2000;4:199–205. doi: 10.1007/s007840000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felden A, Schmalz G, Federlin M, et al. Retrospective clinical investigation and survival analysis on ceramic inlays and partial ceramic crowns: results up to 7 years. Clin Oral Invest. 1998;2:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s007840050064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fradeani M, Aquilano A. Clinical experience with Empress crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 1997;10:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fradeani M, Aquilano A, Corrado M. Clinical experience with In-Ceram Spinell crowns: 5-year follow-up. Int J Periodont Rest Dent. 2002;22:525–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fradeani M, Redemagni M. An 11-year clinical evaluation of leucite-reinforced glass-ceramic crowns: a retrospective study. Quintessence Int. 2002;33:503–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fradeani M, D'Amelio M, Redemagni M, et al. Five-year follow-up with Procera all-ceramic crowns. Quintessence Int. 2005;36:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frankenberger R, Petschelt A, Kramer N. Leucite-reinforced glass ceramic inlays and onlays after six years: clinical behavior. Oper Dent. 2000;25:459–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freilich MA, Meiers JC, Duncan JP, et al. Clinical evaluation of fiber-reinforced fixed bridges. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1524–34. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galindo ML, Sendi P, Marinello CP. Estimating long-term survival of densely sintered alumina crowns: a cohort study over 10 years. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;106:23–28. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(11)60089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gemalmaz D, Ergin S. Clinical evaluation of all-ceramic crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:189–196. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.120653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glantz PO, Nilner K. Patient age and long term survival of fixed prosthodontics. Gerodontology. 1993;10:33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1993.tb00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glantz PO, Nilner K, Jendresen MD. Quality of fixed prosthodontics after twenty-two years. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60:213–218. doi: 10.1080/000163502760147972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groten M, Huttig F. The performance of zirconium dioxide crowns: a clinical follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:429–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gungor MA, Artunc C, Dundar M. Seven-year clinical follow-up study of Probond ceramic crowns. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:e456–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gustavsen F, Silness J. Clinical and radiographic observations after 6 years on bridge abutment teeth carrying pinledge retainers. J Oral Rehabil. 1986;13:295–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1986.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hammerle CH, Ungerer MC, Fantoni PC, et al. Long-term analysis of biologic and technical aspects of fixed partial dentures with cantilevers. Int J Prosthodont. 2000;13:409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haselton DR, Diaz-Arnold AM, Hillis SL. Clinical assessment of high-strength all-ceramic crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:396–401. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)70033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hochman N, Ginio I, Ehrlich J. The cantilever fixed partial denture: a 10-year follow-up. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;58:542–545. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(87)90381-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hochman N, Mitelman L, Hadani PE, et al. A clinical and radiographic evaluation of fixed partial dentures (FPDs) prepared by dental school students: a retrospective study. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:165–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hochman N, Yaffe A, Ehrlich J. Splinting: a retrospective 17-year follow-up study. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:600–602. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holm C, Tidehag P, Tillberg A, et al. Longevity and quality of FPDs: a retrospective study of restorations 30, 20, and 10 years after insertion. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janus CE, Unger JW, Best AM. Survival analysis of complete veneer crowns vs. multisurface restorations: a dental school patient population. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1098–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jokstad A. A split-mouth randomized clinical trial of single crowns retained with resin-modified glass-ionomer and zinc phosphate luting cements. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jokstad A, Mjor IA. Ten years’ clinical evaluation of three luting cements. J Dent. 1996;24:309–315. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(95)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jones JC. The success rate of anterior crowns. Br Dent J. 1972;132:399–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4802852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kantorowicz GF. Bridges: an analysis of failures. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1968;18:176–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karlsson S. A clinical evaluation of fixed bridges, 10 years following insertion. J Oral Rehabil. 1986;13:423–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1986.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katsoulis J, Nikitovic SG, Spreng S, et al. Prosthetic rehabilitation and treatment outcome of partially edentulous patients with severe tooth wear: 3-years results. J Dent. 2011;39:662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kelsey WP, Cavel T, Blankenau RJ, et al. 4-year clinical study of castable ceramic crowns. Am J Dent. 1995;8:259–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kern M, Sasse M, Wolfart S. Ten-year outcome of three-unit fixed dental prostheses made from monolithic lithium disilicate ceramic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:234–240. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kokubo Y, Sakurai S, Tsumita M, et al. Clinical evaluation of Procera All Ceram crowns in Japanese patients: results after 5 years. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:786–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kokubo Y, Tsumita M, Sakurai S, et al. Five-year clinical evaluation of In-Ceram crowns fabricated using GN-I (CAD/CAM) system. J Oral Rehabil. 2011;38:601–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kramer N, Frankenberger R. Clinical performance of bonded leucite-reinforced glass ceramic inlays and onlays after eight years. Dent Mater. 2005;21:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kramer N, Frankenberger R, Pelka M, et al. IPS Empress inlays and onlays after four years—a clinical study. J Dent. 1999;27:325–331. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(98)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kramer N, Taschner M, Lohbauer U, et al. Totally bonded ceramic inlays and onlays after eight years. J Adhes Dent. 2008;10:307–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krieger O, Matuliene G, Husler J, et al. Failures and complications in patients with birth defects restored with fixed dental prostheses and single crowns on teeth and/or implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:809–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laurell L, Lundgren D, Falk H, et al. Long-term prognosis of extensive polyunit cantilevered fixed partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;66:545–552. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90521-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Leempoel PJB, Kayser AF, Van Rossum GM, et al. The survival rate of bridges. A study of 1674 bridges in 40 Dutch general practices. J Oral Rehabil. 1995;22:327–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1995.tb00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lehmann F, Spiegl K, Eickemeyer G, et al. Adhesively luted, metal-free composite crowns after five years. J Adhes Dent. 2009;11:493–498. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.a18144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leirskar J, Nordbo H, Thoresen NR, et al. A four to six years follow-up of indirect resin composite inlays/onlays. Erratum appears in Acta Odontol Scand. Acta Odontol Scand. 2003;61(2003):247–251. doi: 10.1080/00016350310004557. Oct; 61:319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Libby G, Arcuri MR, LaVelle WE, et al. Longevity of fixed partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;78:127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(97)70115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lindquist E, Karlsson S. Success rate and failures for fixed partial dentures after 20 years of service: Part I. Int J Prosthodont. 1998;11:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lops D, Mosca D, Casentini P, et al. Prognosis of zirconia ceramic fixed partial dentures: a 7-year prospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Makarouna M, Ullmann K, Lazarek K, et al. Six-year clinical performance of lithium disilicate fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2011;24:204–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Malament KA, Socransky SS. Survival of Dicor glass-ceramic dental restorations over 14 years: Part I. Survival of Dicor complete coverage restorations and effect of internal surface acid etching, tooth position, gender, and age. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;81:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)70231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Malament KA, Socransky SS. Survival of Dicor glass-ceramic dental restorations over 20 years: Part IV. The effects of combinations of variables. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:134–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mansour YF, Al Omiri MK, Khader YS, et al. Clinical performance of IPS-Empress 2 ceramic crowns inserted by general dental practitioners. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marklund S, Bergman B, Hedlund SO, et al. An intra individual clinical comparison of two metal-ceramic systems: a 5-year prospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:70–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marquardt P, Strub JR. Survival rates of IPS empress 2 all-ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures: results of a 5-year prospective clinical study. Quintessence Int. 2006;37:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martin JA, Bader JD. Five-year treatment outcomes for teeth with large amalgams and crowns. Oper Dent. 1997;22:72–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McLaren EA, White SN. Survival of In-Ceram crowns in a private practice: a prospective clinical trial. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:216–222. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)80015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Milleding P, Haag P, Neroth B, et al. Two years of clinical experience with Procera titanium crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 1998;11:224–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miyamoto T, Morgano SM, Kumagai T, et al. Treatment history of teeth in relation to the longevity of the teeth and their restorations: outcomes of teeth treated and maintained for 15 years. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;97:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Molin MK, Karlsson SL. Five-year clinical prospective evaluation of zirconia-based Denzir 3-unit FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Naeselius K, Arnelund CF, Molin MK. Clinical evaluation of all-ceramic onlays: a 4-year retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Napankangas R, Raustia A. Twenty-year follow-up of metal-ceramic single crowns: a retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Napankangas R, Raustia A. An 18-year retrospective analysis of treatment outcomes with metal-ceramic fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2011;24:314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Napankangas R, Salonen-Kemppi MA, Raustia AM. Longevity of fixed metal ceramic bridge prostheses: a clinical follow-up study. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:140–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nevalainen M, Ruokolainen T, Rantanen T, et al. Comparison of partial and full crowns as retainers in the same bridge. J Oral Rehabil. 1995;22:673–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1995.tb01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oden A, Andersson M, Krystek-Ondracek I, et al. Five-year clinical evaluation of Procera AllCeram crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;80:450–456. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(98)70010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Odman P, Andersson B. Procera AllCeram crowns followed for 5 to 10.5 years: a prospective clinical study. Int J Prosthodont. 2001;14:504–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Oginni AO. Failures related to crowns and fixed partial dentures fabricated in a Nigerian dental school. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:136–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Olsson KG, Furst B, Andersson B, et al. A long-term retrospective and clinical follow-up study of In-Ceram Alumina FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:150–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ortorp A, Kihl ML, Carlsson GE. A 3-year retrospective and clinical follow-up study of zirconia single crowns performed in a private practice. J Dent. 2009;37:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Otto T, De Nisco S. Computer-aided direct ceramic restorations: a 10-year prospective clinical study of Cerec CAD/CAM inlays and onlays. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15:122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Otto T, Schneider D. Long-term clinical results of chairside Cerec CAD/CAM inlays and onlays: a case series. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Owall BE, Almfeldt I, Helbo M. Twenty-year experience with 12-unit fixed partial dentures supported by two abutments. Int J Prosthodont. 1991;4:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Palmqvist S, Swartz B. Artificial crowns and fixed partial dentures 18 to 23 years after placement. Int J Prosthodont. 1993;6:279–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pelaez J, Cogolludo PG, Serrano B, et al. A prospective evaluation of zirconia posterior fixed dental prostheses: Three-year clinical results. J Prosthet Dent. 2012;107:373–379. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(12)60094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Petersson K, Pamenius M, Eliasson A, et al. 20-year follow-up of patients receiving high-cost dental care within the Swedish Dental Insurance System: 1977-1978 to 1998-2000. Swed Dent J. 2006;30:77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Philipp A, Fischer J, Hammerle CH, et al. Novel ceria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia/alumina nanocomposite as framework material for posterior fixed dental prostheses: preliminary results of a prospective case series at 1 year of function. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:313–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Poggio CE, Dosoli R, Ercoli C. A retrospective analysis of 102 zirconia single crowns with knife-edge margins. J Prosthet Dent. 2012;107:316–321. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(12)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Posselt A, Kerschbaum T. Longevity of 2328 chairside Cerec inlays and onlays. Int J Comput Dent. 2003;6:231–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Probster L. Survival rate of In-Ceram restorations. Int J Prosthodont. 1993;6:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Probster L. Four year clinical study of glass-infiltrated, sintered alumina crowns. J Oral Rehabil. 1996;23:147–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1996.tb01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Quinn F, Gratton DR, McConnell RJ. The performance of conventional, fixed bridgework, retained by partial coverage crowns. J Ir Dent Assoc. 1995;41:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Raigrodski AJ, Chiche GJ, Potiket N, et al. The efficacy of posterior three-unit zirconium-oxide-based ceramic fixed partial dental prostheses: a prospective clinical pilot study. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;96:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Randow K, Glantz PO, Zoger B. Technical failures and some related clinical complications in extensive fixed prosthodontics. An epidemiological study of long-term clinical quality. Acta Odontol Scand. 1986;44:241–255. doi: 10.3109/00016358608997726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reich S, Fischer S, Sobotta B, et al. A preliminary study on the short-term efficacy of chairside computer-aided design/computer-assisted manufacturing- generated posterior lithium disilicate crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:214–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Reiss B, Walther W. Clinical long-term results and 10-year Kaplan-Meier analysis of Cerec restorations. Int J Comput Dent. 2000;3:9–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Reitemeier B, Hansel K, Kastner C, et al. Metal-ceramic failure in noble metal crowns: 7-year results of a prospective clinical trial in private practices. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:397–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Reuter JE, Brose MO. Failures in full crown retained dental bridges. Br Dent J. 1984;157:61–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rinke S, Schafer S, Roediger M. Complication rate of molar crowns: a practice-based clinical evaluation. Int J Comput Dent. 2011;14:203–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rinke S, Tsigaras A, Huels A, et al. An 18-year retrospective evaluation of glass-infiltrated alumina crowns. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:625–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Roberts DH. The failure of retainers in bridge prostheses. An analysis of 2,000 retainers. Br Dent J. 1970;128:117–124. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4802433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Roediger M, Gersdorff N, Huels A, et al. Prospective evaluation of zirconia posterior fixed partial dentures: four-year clinical results. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sagirkaya E, Arikan S, Sadik B, et al. A randomized, prospective, open-ended clinical trial of zirconia fixed partial dentures on teeth and implants: interim results. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:221–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sailer I, Feher A, Filser F, et al. Five-year clinical results of zirconia frameworks for posterior fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sailer I, Gottnerb J, Kanelb S, et al. Randomized controlled clinical trial of zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic posterior fixed dental prostheses: a 3-year follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Salido MP, Martinez-Rus F, Del Rio F, et al. Prospective clinical study of zirconia-based posterior four-unit fixed dental prostheses: four-year follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Santos MJ, Mondelli RF, Francischone CE, et al. Clinical evaluation of ceramic inlays and onlays made with two systems: a one-year follow-up. J Adhes Dent. 2004;6:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schmidlin K, Schnell N, Steiner S, et al. Complication and failure rates in patients treated for chronic periodontitis and restored with single crowns on teeth and/or implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:550–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Schmitt J, Holst S, Wichmann M, et al. Zirconia posterior fixed partial dentures: a prospective clinical 3-year follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Schmitt J, Wichmann M, Holst S, et al. Restoring severely compromised anterior teeth with zirconia crowns and feather-edged margin preparations: a 3-year follow-up of a prospective clinical trial. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:107–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Schmitter M, Mussotter K, Rammelsberg P, et al. Clinical performance of long-span zirconia frameworks for fixed dental prostheses: 5-year results. J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:552–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2012.02311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Schulte AG, Vockler A, Reinhardt R. Longevity of ceramic inlays and onlays luted with a solely light-curing composite resin. J Dent. 2005;33:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Scotti R, Catapano S, D'Elia A. A clinical evaluation of In-Ceram crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 1995;8:320–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Segal BS. Retrospective assessment of 546 all-ceramic anterior and posterior crowns in a general practice. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;85:544–550. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2001.115180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Signore A, Benedicenti S, Covani U, et al. A 4- to 6-year retrospective clinical study of cracked teeth restored with bonded indirect resin composite onlays. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Sjögren G, Lantto R, Granberg A, et al. Clinical examination of leucite-reinforced glass-ceramic crowns (Empress) in general practice: a retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 1999;12:122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Sjögren G, Lantto R, Tillberg A. Clinical evaluation of all-ceramic crowns (Dicor) in general practice. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;81:277–284. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)70269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Smales RJ, Etemadi S. Survival of ceramic onlays placed with and without metal reinforcement. J Prosthet Dent. 2004;91:548–553. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Smales RJ, Hawthorne WS. Long-term survival of repaired amalgams, recemented crowns and gold castings. Oper Dent. 2004;29:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Smedberg JI, Ekenback J, Lothigius E, et al. Two-year follow-up study of Procera-ceramic fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 1998;11:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sorensen JA, Choi C, Fanuscu MI, et al. IPS Empress crown system: three-year clinical trial results. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1998;26:130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sorensen JA, Cruz M, Mito WT, et al. A clinical investigation on three-unit fixed partial dentures fabricated with a lithium disilicate glass-ceramic. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1999;11:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Sorensen JA, Kang SK, Torres TJ, et al. In-Ceram fixed partial dentures: three-year clinical trial results. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1998;26:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Steeger B. Survival analysis and clinical follow-up examination of all-ceramic single crowns. Int J Comput Dent. 2010;13:101–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Stoll R, Cappel I, Jablonski-Momeni A, et al. Survival of inlays and partial crowns made of IPS empress after a 10-year observation period and in relation to various treatment parameters. Oper Dent. 2007;32:556–563. doi: 10.2341/07-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Stoll R, Sieweke M, Pieper K, et al. Longevity of cast gold inlays and partial crowns—a retrospective study at a dental school clinic. Clin Oral Invest. 1999;3:100–104. doi: 10.1007/s007840050086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Studer S, Lehner C, Brodbeck U, et al. Short-term results of IPS-Empress inlays and onlays. J Prosthodont. 1996;5:277–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1996.tb00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Studer SP, Wettstein F, Lehner C, et al. Long-term survival estimates of cast gold inlays and onlays with their analysis of failures. J Oral Rehabil. 2000;27:461–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2000.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Suarez MJ, Lozano JF, Paz SM, et al. Three-year clinical evaluation of In-Ceram Zirconia posterior FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Sundh B, Odman P. A study of fixed prosthodontics performed at a university clinic 18 years after insertion. Int J Prosthodont. 1997;10:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Tagtekin DA, Ozyoney G, Yanikoglu F. Two-year clinical evaluation of IPS Empress II ceramic onlays/inlays. Oper Dent. 2009;34:369–378. doi: 10.2341/08-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Tan K, Chan ES, Sim CP, et al. A 5-year retrospective study of fixed partial dentures: success, survival, and incidence of biological and technical complications. Singapore Dent J. 2006;28:40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Tara MA, Eschbach S, Bohlsen F, et al. Clinical outcome of metal-ceramic crowns fabricated with laser-sintering technology. Int J Prosthodont. 2011;24:46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Tartaglia GM, Sidoti E, Sforza C. A 3-year follow-up study of all-ceramic single and multiple crowns performed in a private practice: a prospective case series. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:2063–2070. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011001200011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Taskonak B, Sertgoz A. Two-year clinical evaluation of lithia-disilicate-based all-ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures. Dent Mater. 2006;22:1008–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Toksavul S, Toman M. A short-term clinical evaluation of IPS Empress 2 crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:168–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Valderhaug J. A 15-year clinical evaluation of fixed prosthodontics. Acta Odontol Scand. 1991;49:35–40. doi: 10.3109/00016359109041138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Valderhaug J, Jokstad A, Ambjornsen E, et al. Assessment of the periapical and clinical status of crowned teeth over 25 years. J Dent. 1997;25:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(96)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Valenti M, Valenti A. Retrospective survival analysis of 261 lithium disilicate crowns in a private general practice. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:573–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Vanoorbeek S, Vandamme K, Lijnen I, et al. Computer-aided designed/computer-assisted manufactured composite resin versus ceramic single-tooth restorations: a 3-year clinical study. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Vult von Steyern P, J¨onsson O, Nilner K. Five-year evaluation of posterior all-ceramic three-unit (In-Ceram) FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2001;14:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Vult von Steyern P, Carlson P, Nilner K. All-ceramic fixed partial dentures designed according to the DC-Zirkon technique. A 2-year clinical study. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Wagner J, Hiller KA, Schmalz G. Long-term clinical performance and longevity of gold alloy vs ceramic partial crowns. Clin Oral Invest. 2003;7:80–85. doi: 10.1007/s00784-003-0205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Walter M, Reppel PD, Boning K, et al. Six-year follow-up of titanium and high-gold porcelain-fused-to-metal fixed partial dentures. J Oral Rehabil. 1999;26:91–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1999.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Walter MH, Wolf BH, Wolf AE, et al. Six-year clinical performance of all-ceramic crowns with alumina cores. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:162–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Walton JN, Gardner FM, Agar JR. A survey of crown and fixed partial denture failures: length of service and reasons for replacement. J Prosthet Dent. 1986;56:416–421. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(86)90379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Walton TR. A ten-year longitudinal study of fixed prosthodontics: 1. Protocol and patient profile. Int J Prosthodont. 1997;10:325–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Walton TR. A 10-year longitudinal study of fixed prosthodontics: clinical characteristics and outcome of single-unit metal-ceramic crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 1999;12:519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Walton TR. An up to 15-year longitudinal study of 515 metal-ceramic FPDs: Part 1. Outcome. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15:439–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Walton TR. Changes in the outcome of metal-ceramic tooth-supported single crowns and FDPs following the introduction of osseointegrated implant dentistry into a prosthodontic practice. [Erratum appears in Int J Prosthodont. 2009 Jul-Aug; 22(4):353] Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:260–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Wolfart S, Bohlsen F, Wegner SM, et al. A preliminary prospective evaluation of all-ceramic crown-retained and inlay-retained fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18:497–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Wolfart S, Harder S, Eschbach S, et al. Four-year clinical results of fixed dental prostheses with zirconia substructures (Cercon): end abutments vs. cantilever design. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:741–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Wolleb K, Sailer I, Thoma A, et al. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of patients receiving both tooth- and implant-supported prosthodontic treatment after 5 years of function. Int J Prosthodont. 2012;25:252–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Zarone F, Sorrentino R, Vaccaro F, et al. Retrospective clinical evaluation of 86 Procera AllCeram anterior single crowns on natural and implant-supported abutments. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2005.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Zitzmann NU, Galindo ML, Hagmann E, et al. Clinical evaluation of Procera AllCeram crowns in the anterior and posterior regions. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:239–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Ballini A, Capodiferro S, Toia M, et al. Evidence-based dentistry: what's new? Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:174–178. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chadwick B, Treasure E, Dummer P, et al. Challenges with studies investigating longevity of dental restorations—a critique of a systematic review. J Dent. 2001;29:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(01)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jokstad A, Bayne S, Blunck U, et al. Quality of dental restorations. FDI Commission Project 2–95. Int Dent J. 2001;51:117–158. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vervölgyi E, Kromp M, Skipka G, et al. Reporting of loss to follow-up information in randomised controlled trials with time-to-event outcomes: a literature survey. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Gourgou-Bourgade S, Bonnetain F, et al. Survival end point reporting in randomized cancer clinical trials: a review of major journals. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3721–3726. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Schulz KF. Randomized controlled trials in cancer: improving the quality of their reports will also facilitate better conduct. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:483–487. doi: 10.1023/a:1008294904298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cioffi I, Farella M. Quality of randomised controlled trials in dentistry. Int Den J. 2011;61:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, et al. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature—part 1. Effects of study characteristics on probability of success. Int Endod J. 2007;40:921–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papageorgiou SN, Papadopoulos MA, Athanasiou AE. Evaluation of methodology and quality characteristics of systematic reviews in orthodontics. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2011;14:116–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2011.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Namankany AA, Ashley P, Moles DR, et al. Assessment of the quality of reporting of randomized clinical trials in paediatric dentistry journals. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torabinejad M, Anderson P, Bader J, et al. Outcomes of root canal treatment and restoration, implant-supported single crowns, fixed partial dentures, and extraction without replacement: a systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98:285–311. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meijer HJ, Raghoebar GM. Quality of reporting of descriptive studies in implant dentistry. Critical aspects in design, outcome assessment and clinical relevance. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(Suppl 12):108–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jokstad A, Esposito M, Coulthard P, et al. The reporting of randomized controlled trials in prosthodontics. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15:230–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan K, Pjetursson BE, Lang NP, et al. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of fixed partial dentures (FPDs) after an observation period of at least 5 years. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:654–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong C, Ivanovski S, Needleman I, et al. Implant survival and success in patients treated for periodontitis—a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:438–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pjetursson BE, Bragger U, Lang NP, et al. Comparison of survival and complication rates of tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) and implant-supported FDPs and single crowns (SCs) Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18(Suppl 3):97–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scurria MS, Bader JD, Shugars DA. Meta-analysis of fixed partial denture survival: prostheses and abutments. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;79:459–464. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(98)70162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Needleman I, Chin S, O'Brien T, et al. Systematic review of outcome measurements and reference group(s) to evaluate and compare implant success and failure. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(Suppl 12):122–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cvar JF, Ryge G. Reprint of criteria for the clinical evaluation of dental restorative materials. 1971. Clin Oral Investig. 2005;9:215–232. doi: 10.1007/s00784-005-0018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.California Dental Association: Guidelines for the Assessment of Clinical Quality and Professional Performance (ed 3) Sacramento: California Dental Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]