Abstract

Although Methotrexate (MTX) is an effective drug for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the toxicity remains a significant problem. In this prospective study, fifty-four patients with ALL were enrolled. 3 g or 5 g MTX/m2 was administered over 24 hours. Serum MTX concentrations were determined in 24, 48, and 96 hours after MTX infusion. Serum creatinine concentrations and creatinine clearance rate (CCR) were determined before and 24 and 48 hours after MTX infusion. A total of 173 courses of MTX infusion were administered. The serum creatinine concentrations did not change much after MTX infusion while the CCR was gradually decreased. MTX clearance status was independently related to CCR decrease, with the risk of 8.07 to develop renal impairment in patients with delayed MTX elimination. Serum creatinine concentration, serum creatinine ratio, CCR, and CCR ratio at 24 hours were all related to MTX elimination delay. Patients with serum creatinine level >35.0 μmol/L, creatinine ratio >1.129, or CCR <100.0 mL/min were more likely to undergo MTX elimination delay. In conclusion, MTX could induce transient renal impairment and compromised renal function will delay MTX clearance. The serum creatinine concentration and the ratio and CCR are useful tools for evaluating MTX elimination status.

1. Introduction

Methotrexate (MTX) is one of the essential agents for the extramedullary leukemia prophylaxis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and osteosarcoma protocols, which has led to significant improvements in the long-term survival of these patients [1–5]. Genetic polymorphisms relating to MTX metabolism significantly affect long-term survival of patients with ALL [6, 7]. Different from other antineoplastic drugs, the cytotoxic effects of MTX can be partially antagonized by folic acid (leucovorin), which allows us to use the high-dose intravenous MTX up to 33.6 g/m2 [3, 8]. However, MTX related toxicity remains an important issue even by now, which includes nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal mucositis, bone marrow suppression, and neurotoxicity [9–11]. The toxicity is even severer in patients with elimination delay of MTX [12].

In order to predict severe adverse events during high-dose MTX (HD-MTX) chemotherapy, many pharmacokinetic models of HD-MTX infusion have been developed [13–15]; however, these models are complicated and not very helpful in clinical practice. On the one hand, besides MTX itself, the patient's pharmacogenomics, organ function, and the coadministrated anticancer agents may influence the normal elimination of MTX. On the other hand, these models were not informative enough for patients with delayed MTX elimination. Therefore, serum MTX concentration monitoring is still a standard approach for identifying patients at high risk of developing toxicity. However, there are still many oncological institutions that cannot carry out serum MTX concentration measurement in China, so it is of great importance to find a simple and convenient way to screen out patients at high risk of developing toxicity.

It is well known that renal clearance is the principal pathway of MTX elimination, and its elimination appears to be related to renal function [16, 17]. On the other hand, nephrotoxicity is one of the most frequently reported side effects of HD-MTX infusion, especially in patients with delayed MTX elimination. Thus, it is important to illustrate the association between renal function and MTX elimination, which could guide the clinical decision making to prevent severe adverse events.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the change of renal function after administration of HD-MTX by parameters such as serum creatinine and creatinine clearance rate (CCR) and to find out helpful parameters that can be used to predict delayed MTX elimination and to prevent renal impairment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Fifty-four patients with newly diagnosed ALL from April 2014 to February 2015 were enrolled in this study after informed consent was obtained. All of these patients were treated with modified National Protocol of Childhood Leukemia in China 2006 (NPCLC-ALL2006) [18]. Of the 54 patients, 33 were boys and 21 were girls, with a median age of 5.4 years (range from 2.2 years to 15.0 years). According to risk stratification, 12 patients were from high risk group, 9 from intermediate risk group, and 33 from low risk group. The diagnostic and the risk grouping criteria were as previously described [18]. A total of 173 courses of MTX were administered.

2.2. MTX Administration and Serum MTX Concentration Determination

The total MTX dose was 3 g/m2 for low risk group and 5 g/m2 for intermediate and high risk groups. For each course, 1/6 of the total MTX dose (maximum to 0.5 g) was given intravenously in the first hour and the rest was administered evenly during the subsequent 23 hours. Intravenous hydration and urinary alkalinization were performed one day before HD-MTX administration at doses of 2000–3000 mL/m2/d for low risk patients and 3000–4000 mL/m2/d for intermediate and high risk patients with 5% of sodium bicarbonate at a dosage of 5 mL/kg/d. Intravenous hydration and urinary alkalinization were continued during and after MTX infusion until the MTX serum concentration was <0.1 μmol/L.

The serum MTX concentration was determined by fluorescent polarization immunoassay at 24, 48, and 96 hours after MTX administration and was further detected until the concentration was below 0.1 μmol/L. Patients with serum MTX concentrations ≥1.0 μmol/L at 48 hours or ≥0.1 μmol/L at 96 hours were considered as elimination delay [12]. Leucovorin was administered on the time of 42 hours after MTX administration as an intravenous bolus every 6 hours for 3 to 8 doses or until the serum MTX concentration was <0.1 μmol/L.

2.3. Assessment of Renal Function

Creatinine clearance using 24-hour urine collection had been measured in all patients before and 24 and 48 hours after the initiation of HD-MTX treatment. A portion of the collection was used to measure the urinary creatinine concentration, and a venous blood sample was drawn for the measurement of serum creatinine level in the last hour of urine sample collection. The following formula was used to calculate the CCR: CCR = [urine creatinine (mg/dL) × 24 hour urine volume (mL) × 1.73 m2]/[body surface area (m2) × serum creatinine (mg/dL) × 1440]. Serum creatinine ratio was calculated using the following formula: serum creatinine ratio = serum creatinine (mg/dL) at 48 hours or 96 hours/serum creatinine (mg/dL) before MTX infusion and CCR ratio = CCR at 48 hours or 96 hours/CCR before MTX infusion.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The comparisons of patients' demographic features and creatinine metabolism parameters between normal and delayed MTX elimination groups were performed by Mann-Whitney U test. Increase of serum creatinine level and decrease of CCR in every group were compared by Wilcoxon signed rank test. The selection of parameters related to renal impairment (CCR decrease >50%) was performed using binary logistic regression model. The correlations between creatinine metabolism parameters and serum MTX concentrations were determined by Spearman's rank correlation analysis. The predictive power of creatinine level, ratio, and CCR for MTX elimination were evaluated by receiver's operating characteristic (ROC) curve; the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated by χ 2 test. All analyses were performed on SPSS12.0 software. A P value < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to be of statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Patients' Characteristics

A total of 173 courses of MTX infusion were observed in this study. As for dosages, 113 courses were 3 g/m2 and 60 courses were 5 g/m2. Forty-eight episodes of elimination delay were observed, accounting for 27.7% of total courses. The rate of elimination delay showed no difference between 3 g/m2 group (31.9%, 36/113) and 5 g/m2 group (20.0%, 12/60) (P = 0.097). Gastrointestinal adverse reaction such as nausea and vomiting, oral mucositis, and bone marrow depression were the most common toxic effects. Thirty-two episodes of febrile neutropenia occurred. Hepatic impairment was found in 63 infusions. No fatal adverse event occurred in this cohort. We compared the demographic features and some potential characteristics that may be correlated with MTX elimination, including age, height, weight, body surface area (BSA), serum creatinine level, serum creatinine ratio, urine output (adjusted to BSA), and CCR. As shown in Table 1, patient demographic characteristics, including gender, age, weight, and BSA, were comparable between the delayed elimination group and the normal elimination group as well. However, patients with MTX clearance delay showed higher serum creatinine concentrations, higher serum creatinine ratios, and severer CCR decrease at 24 hours and 48 hours.

Table 1.

Comparison of patients' characteristics and serum MTX concentrations between patients with and without MTX elimination delay.

| Characteristics | Whole cohort | Number ratio | Normal elimination | Delayed elimination | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | 110 | 123 versus 50 | 110.0 | 108.5 | 0.629 |

| Weight (kg) | 19.0 | 123 versus 50 | 20.0 | 19.0 | 0.493 |

| Age (year) | 5.2 | 123 versus 50 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 0.461 |

| BSA (m2) | 0.85 | 123 versus 50 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.615 |

| S-creatinine 0 h (μmol/L) | 31.7 | 110 versus 41 | 32.8 | 30.9 | 0.083 |

| S-creatinine 24 h (μmol/L) | 33.5 | 120 versus 48 | 31.6 | 42.5 | <0.001 |

| S-creatinine 48 h (μmol/L) | 33.8 | 122 versus 50 | 30.5 | 47.4 | <0.001 |

| S-creatinine ratio 24 h | 1.02 | 110 versus 41 | 0.98 | 1.26 | <0.001 |

| S-creatinine ratio 48 h | 1.01 | 110 versus 41 | 0.95 | 1.39 | <0.001 |

| CCR_0 h (mL/min) | 131.3 | 111 versus 41 | 130.1 | 139.5 | 0.424 |

| CCR_24 h (mL/min) | 111.3 | 118 versus 48 | 120.2 | 85.1 | <0.001 |

| CCR_48 h (mL/min) | 102.7 | 120 versus 49 | 114.1 | 81.7 | <0.001 |

| CCR_96 h (mL/min) | 97.7 | 12 versus 17 | 113.8 | 86.4 | 0.008 |

| C MTX_24 h (μmol/L) | 59.8 | 123 versus 50 | 54.5 | 70.5 | <0.001 |

| C MTX_48 h (μmol/L) | 0.43 | 123 versus 50 | 0.32 | 2.81 | <0.001 |

| C MTX_96 h (μmol/L) | 0.04 | 115 versus 49 | 0.02 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

S-creatinine 0 h: serum creatinine level before MTX infusion; S-creatinine 24 h: serum creatinine level in 24 hours after MTX infusion; S-creatinine 48 h: serum creatinine level in 48 hours after MTX infusion; S-creatinine ratio 24 h: the ratio of serum creatinine level in 24 hours to creatinine level before MTX infusion; S-creatinine ratio 48 h: the ratio of serum creatinine level in 48 hours to creatinine level before MTX infusion; CCR_0 h: creatinine clearance rate before MTX infusion; CCR_24 h: creatinine clearance rate in 24 hours after MTX infusion; CCR_48 h: creatinine clearance rate in 48 hours after MTX infusion; CCR_96 h: creatinine clearance rate in 96 hours after MTX infusion; C MTX_24 h: serum MTX concentration in 24 hours after MTX infusion; C MTX_48 h: serum MTX concentration in 48 hours after MTX infusion; C MTX_96 h: serum MTX concentration in 96 hours after MTX infusion.

3.2. Renal Impairment in HD-MTX Chemotherapy

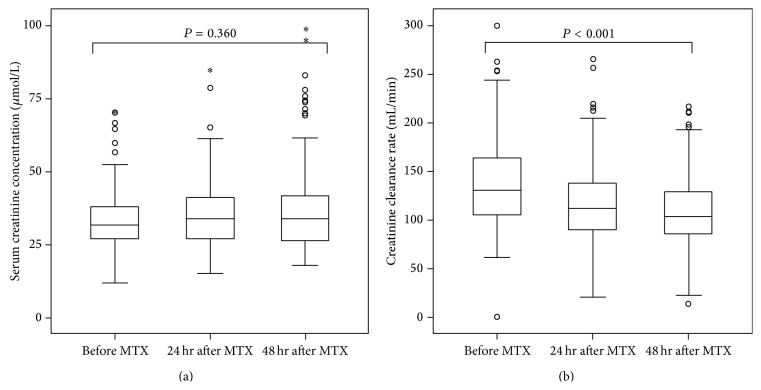

We first assessed renal function change after HD-MTX infusion by serum creatinine and CCR. As shown in Figure 1, the serum creatinine concentrations did not change much in 24 hours and 48 hours after HD-MTX infusion when compared with that before chemotherapy (median concentrations, 0 hours versus 24 hours versus 48 hours: 31.7 μmol/L versus 33.5 μmol/L versus 33.8 μmol/L, P = 0.360). However, the CCR level was gradually decreased after HD-MTX infusion (median concentrations, 0 hours versus 24 hours versus 48 hours: 131.2 mL/min versus 112.3 mL/min versus 102.7 mL/min, P < 0.001), indicating the renal function impairment after HD-MTX chemotherapy. It also revealed that CCR was a more sensitive marker to assess renal function in this situation.

Figure 1.

Serum creatinine (a) and creatinine clearance rate (CCR) change (b) after MTX infusion.

3.3. Delayed MTX Elimination Was Significantly Related to Renal Impairment

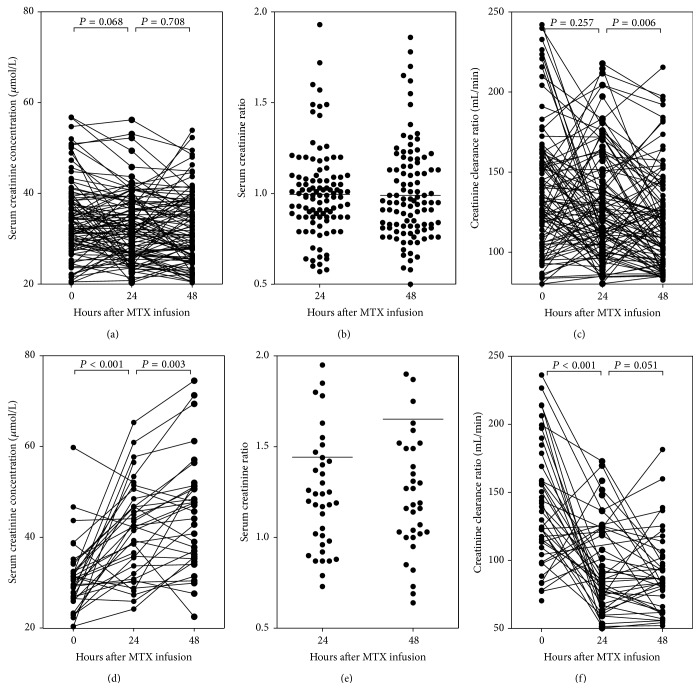

As CCR was a good marker for renal function, we then defined CCR decrease more than 50% in 48 hours compared with that before HD-MTX infusion as renal impairment. Parameters probably related to renal impairment were collected in Table 2, including age, body surface area, MTX dose, creatinine level before MTX infusion, MTX concentration in 24 hours, and MTX clearance status in 48 hours. Only MTX clearance status was independently related to CCR decrease, with the risk of 8.07 (95% CI, 2.57–25.32) to develop renal impairment in patients with delayed MTX elimination. We further investigated the serum creatinine, serum creatinine ratio, and CCR change during HD-MTX infusion in normal MTX elimination group and delayed MTX elimination group, respectively (Figure 2), and found that both serum creatinine and serum creatinine ratio were significantly increased while CCR was markedly decreased in delayed MTX elimination group. However, only CCR was slightly decreased between 24 hours and 48 hours after MTX infusion in normal MTX elimination group.

Table 2.

Possible parameters related to CCR decrease > 50%.

| Parameters | Standard | Number ratio | Relative risk | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥10 years | <10 years | 41 versus 132 | 0.81 | 0.09–7.30 | 0.852 |

| Body surface area ≥1.0 m2 | <1.0 m2 | 51 versus 122 | 1.77 | 0.24–12.96 | 0.573 |

| MTX dosage (≥5 g/m2) | <5 g/m2 | 60 versus 113 | 0.98 | 0.24–4.10 | 0.979 |

| S-creatinine 0 h ≥35 μmol/L | <35 μmol/L | 58 versus 115 | 0.31 | 0.07–1.44 | 0.134 |

| C MTX_24 h ≥65 μmol/L | <65 μmol/L | 74 versus 99 | 0.83 | 0.26–2.65 | 0.758 |

| Delayed MTX elimination | Normal elimination | 53 versus 120 | 8.07 | 2.57–25.32 | <0.001 |

S-creatinine 0 h: serum creatinine level before MTX infusion; C MTX_24 h: serum MTX concentration in 24 hours after MTX infusion.

Figure 2.

Comparison of renal function in normal and delayed MTX elimination. In normal MTX elimination patients, serum creatinine concentration (a) and creatinine ratio (b) were comparable while the CCR was slightly decreased 24 hours after MTX infusion (c). In delayed MTX elimination patients, serum creatinine concentration (d) and creatinine ratio (e) were gradually increased while CCR was decreased (f).

3.4. Biomarkers to Predict Delayed MTX Elimination

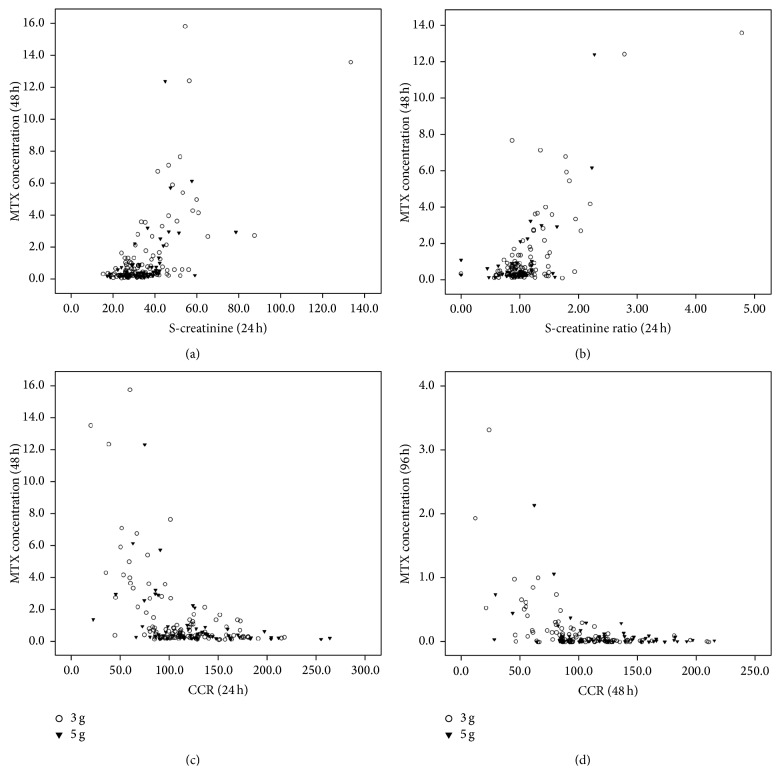

As MTX elimination delay was significantly related to renal impairment, if the physician could predict MTX elimination delay in an early time and give proper intervention, the renal toxicity and other complications related to MTX elimination delay might be alleviated. In order to screen out parameters that can be used to predict MTX clearance delay, the correlations between the serum metabolism and MTX concentrations at 48 hours and 96 hours were analyzed. As shown in Figure 3, serum creatinine concentration at 24 hours was positively related to the MTX concentrations at 48 hours (r = 0.525, P < 0.001) and 96 hours (r = 0.577, P < 0.001). Moreover, serum creatinine ratio at 24 hours seemed more closely related to the MTX concentrations at 48 hours (r = 0.749, P < 0.001) and 96 hours (r = 0.764, P < 0.001), respectively. CCR at 24 hours was inversely related to the MTX concentration at 48 hours (r = −0.398, P < 0.001) and 96 hours (r = −0.331, P < 0.001), and CCR ratio at 24 hours was only slightly related to the MTX concentration at 48 hours (r = −0.356, P < 0.001) and 96 hours (r = −0.289, P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

The correlations between serum creatinine concentration (μmol/L), the ratio of serum creatinine level in 24 hours to creatinine level before MTX infusion (S-creatinine ratio), creatinine clearance rate (CCR, mL/min), and serum MTX concentration (μmol/L) in 3 g/m2 (unfilled circle) and 5 g/m2 groups (filled inverted triangle).

As all the four parameters were related to MTX elimination delay, we then further assessed their function in predicting MTX elimination delay. As shown in Table 3, serum creatinine 24 hours after MTX infusion, serum creatinine ratio (24 hours), CCR (24 hours), and CCR ratio (24 hours) all predict MTX elimination delay by ROC analysis, with the accuracy around 75%. We found that patients with serum creatinine level >35.0 μmol/L, serum creatinine ratio >1.129, CCR level <100.0 mL/min, and CCR ratio <0.824 more likely experienced MTX elimination delay. Serum creatinine ratio seemed to be the best marker for the prediction. When serum creatinine concentration was >46.0 μmol/L, serum creatinine ratio was >1.5, CCR level was <80.0 mL/min, or/and CCR ratio was <0.59, the probability for elimination delay was more than 95%.

Table 3.

The predictive value of S-creatinine, S-creatinine ratio, and CCR for delayed MTX elimination.

| Parameters | AUC | P value | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-creatinine 24 h | 0.756 (0.672–0.840) | <0.001 | >35.0 | 68.6% | 70.1% |

| S-creatinine ratio 24 h | 0.759 (0.668–0.850) | <0.001 | >1.129 | 69.8% | 80.0% |

| CCR_24 h | 0.771 (0.688–0.854) | <0.001 | <100.0 | 68.6% | 74.1% |

| CCR ratio 24 h | 0.728 (0.626–0.829) | <0.001 | <0.824 | 67.4% | 73.1% |

| S-creatinine 0 h | 0.422 (0.324–0.519) | 0.130 | |||

| CCR_0 h | 0.509 (0.409–0.608) | 0.859 |

S-creatinine 24 h: serum creatinine level in 24 hours after MTX infusion; S-creatinine ratio 24 h: the ratio of serum creatinine level in 24 hours to creatinine level before MTX infusion; CCR_24 h: creatinine clearance rate in 24 hours after MTX infusion; CCR ratio 24 h: the ratio of CCR in 24 hours to CCR before MTX infusion; S-creatinine 0 h: serum creatinine level before MTX infusion; CCR_0 h: creatinine clearance rate before MTX infusion.

4. Discussion

The present study shows that HD-MTX administration induces temporal CCR decrease, and the elevated creatinine level, the high creatinine ratio, and the decrease of CCR are closely related to delayed MTX elimination. These findings indicate that HD-MTX can induce transient kidney impairment and compromised kidney function will delay MTX clearance. However, none of the parameters for renal function measured before the start of HD-MTX infusion was found to be correlated with MTX elimination.

Renal clearance is the main pathway for MTX elimination. About 70%~90% of the dose is excreted unchanged in the urine [19]. It has been reported that increased serum creatinine level during HD-MTX infusion is often associated with delayed MTX elimination [16], which is consistent with the present study. Nevertheless, this study also found that patients experienced a short time decrease of CCR after MTX infusion, which confirmed that HD-MTX administration can induce transient renal function impairment [20, 21]. However, CCR is a more sensitive parameter for predicting kidney impairment when compared with serum creatinine level, especially for patients with normal MTX elimination. Of the “normal” patients, although minimal impairment of renal function occurred according to CCR, the creatinine showed no elevation, which was similar to Skärby et al.'s and Ylinen et al.'s results [16, 22]. This may be attributed to the compensation of kidney to maintain serum creatinine concentrations stable.

The relationship between serum MTX concentration and creatinine clearance was controversial. Studies from Evans, Relling, and Joannon all reported that there was no correlation between serum MTX concentration and creatinine clearance [2, 11, 23]. In these studies, the MTX dosages were 1 g, 0.9~3.7 g, and 1~2 g, respectively, which were lower than the dosage in the present study. The MTX concentrations in 24 and 48 hours were much lower as well, which implied that patients in these studies might undergo a lesser degree of renal function impairment according to Hempel et al. [21]. As kidney has powerful compensatory capacity [24], slight impairment has minimal influence on its clearance of MTX. Thus the dose-responses effect of CCR variation on MTX elimination may not be obvious to a certain extent in these patients. This was similar to normal elimination group in this study.

This study illustrated the relationship between renal function and MTX elimination. According to the creatinine change and CCR level, physicians could evaluate the MTX elimination status 24 hours before MTX concentration report and adjust alkalization and hydration as early as possible, so that the toxicity of MTX could be reduced. In some institutions where MTX concentration detection cannot be performed, creatinine and CCR investigation can be a useful tool to find out patients with high risk of delayed MTX elimination. For patients with normal renal function, regular alkalization, hydration, and leucovorin can be used. However, for patients with high creatinine level/ratio or low CCR level, they are likely to undergo delayed MTX elimination, so the remedies to improve renal function and increase MTX clearance should be applied accordingly.

Abbreviations

- MTX:

Methotrexate

- ALL:

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- CCR:

Creatinine clearance rate.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Shi-Long Yang and Fen-Ying Zhao contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Mantadakis E., Cole P. D., Kamen B. A. High-dose methotrexate in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: where is the evidence for its continued use? Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(5):748–755. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.5.748.63584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans W. E., Crom W. R., Stewart C. F., et al. Methotrexate systemic clearance influences probability of relapse in children with standard-risk acute lymphocytic leukaemia. The Lancet. 1984;1(8373):359–362. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans W. E., Crom W. R., Abromowitch M., et al. Clinical pharmacodynamics of high-dose methotrexate in acute lymphocytic leukemia. Identification of a relation between concentration and effect. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314(8):471–477. doi: 10.1056/nejm198602203140803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choeyprasert W., Pakakasama S., Sirachainan N., et al. Comparative outcome of Thai pediatric osteosarcoma treated with two protocols: the role of high-dose methotrexate (HDMTX) in a single institute experience. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2014;15(22):9823–9829. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.22.9823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., Xu Y., Lin N., Jiang S., Wang Y., Ye Z. High-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) used as an adjunct with other chemotherapeutics for the treatment of osteosarcoma. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2015;71(2):1097–1104. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gómez-Gómez Y., Organista-Nava J., Rangel-Rodriguez C., et al. Effect of folylpolyglutamate synthase A22G polymorphism on the risk and survival of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncology Letters. 2014;8:731–735. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gómez-Gómez Y., Organista-Nava J., Saavedra-Herrera M. V., et al. Survival and risk of relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a Mexican population is affected by dihydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2012;3(4):665–672. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen I. J. Defining the appropriate dosage of folinic acid after high-dose methotrexate for childhood acute lymphatic leukemia that will prevent neurotoxicity without rescuing malignant cells in the central nervous system. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2004;26(3):156–163. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Štěrba J., Valík D., Bajčiová V., Kadlecová V., Gregorová V., Mendelová D. High-dose methotrexate and/or leucovorin rescue for the treatment of children with lymphoblastic malignancies: do we really know why, when and how? Neoplasma. 2005;52(6):456–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmiegelow K. Advances in individual prediction of methotrexate toxicity: a review. British Journal of Haematology. 2009;146(5):489–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Relling M. V., Fairclough D., Ayers D., et al. Patient characteristics associated with high-risk methotrexate concentrations and toxicity. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1994;12(8):1667–1672. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu W., Tang Y., Song H., Shi S., Yang S. Retrospective study on elimination delay of methotrexate in high-dose therapy of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in China. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2007;29(10):688–693. doi: 10.1097/mph.0b013e31814d6777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piard C., Bressolle F., Fakhoury M., et al. A limited sampling strategy to estimate individual pharmacokinetic parameters of methotrexate in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2007;60(4):609–620. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min Y., Qiang F., Peng L., Zhu Z. High dose methotrexate population pharmacokinetics and bayesian estimation in patients with lymphoid malignancy. Biopharmaceutics and Drug Disposition. 2009;30(8):437–447. doi: 10.1002/bdd.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aumente D., Buelga D. S., Lukas J. C., Gomez P., Torres A., García M. J. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2006;45(12):1227–1238. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645120-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skärby T., Jönsson P., Hjorth L., et al. High-dose methotrexate: on the relationship of methotrexate elimination time vs renal function and serum methotrexate levels in 1164 courses in 264 Swedish children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2003;51(4):311–320. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0552-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuhara K., Ikawa K., Morikawa N., Kumagai K. Population pharmacokinetics of high-dose methotrexate in Japanese adult patients with malignancies: a concurrent analysis of the serum and urine concentration data. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2008;33(6):677–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Y., Xu X., Song H., Yang S., Shi S., Wei J. Long-term outcome of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated in China. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2008;51(3):380–386. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adamson P. C., Balis F. M., Berg W., Blaney S. M. General principles of chemotherapy. In: Pizzo P. A., Poplack D. G., editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 5th. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 290–365. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abelson H. T., Fosburg M. T., Beardsley G. P., et al. Methotrexate-induced renal impairment: clinical studies and rescue from systemic toxicity with high-dose leucovorin and thymidine. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1983;1(3):208–216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.3.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hempel L., Misselwitz J., Fleck C., et al. Influence of high-dose methotrexate therapy (HD-MTX) on glomerular and tubular kidney function. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 2003;40(6):348–354. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ylinen E., Jahnukainen K., Saarinen-Pihkala U. M., Jahnukainen T. Assessment of renal function during high-dose methotrexate treatment in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2014;61(12):2199–2202. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joannon P., Oviedo I., Campbell M., Tordecilla J. High-dose methotrexate therapy of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: lack of relation between serum methotrexate concentration and creatinine clearance. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2004;43(1):17–22. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borsi J. D., Moe P. J. Systemic clearance of methotrexate in the prognosis of acute lymphoblastic leukmia in children. Cancer. 1987;60(12):3020–3024. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871215)60:12<3020::AID-CNCR2820601227>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]