Abstract

Background: Given the shortage of medical professionals in the Philippines, Barangay Health Workers (BHWs) may play a role in providing postpartum healthcare services. However, as there are no reports regarding BHW activities in postpartum healthcare, we conducted this study to understand postpartum healthcare services and to explore the challenges and motivations of maternal health service providers.

Methods: Focus group interview (FGI) of 13 participants was conducted as qualitative research methodology at Muntinlupa City. The results were analyzed according to the interview guide. The proceedings of the FGI were transcribed verbatim, and researchers read and coded the transcripts. The codes were then used to construct categories.

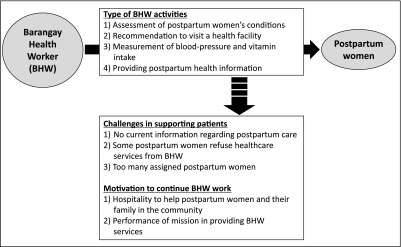

Results: Four important activities were highlighted among 11 analysis codes. These activities were “Assessment of postpartum women’s conditions,” “Recommendation to visit a health facility,” “Measurement of blood-pressure and vitamin intake,” and “Providing postpartum health information.” Among five analysis codes, we identified three challenges that BHWs face, which were “No current information regarding postpartum care,” “Some postpartum women do not want to receive healthcare services from BHW,” and “Too many assigned postpartum women.” Among five analysis codes, we identified two reasons for continuing BHW activities, which were “Hospitality to help postpartum women and their family in the community” and “Performance of mission in providing BHW services.”

Conclusion: This study is the first to evaluate BHW activities in postpartum healthcare services. Our results indicate that BHWs play a potentially important role in evaluating postpartum women’s physical and mental conditions through home-visiting services. However, several difficulties adversely affected their activities, and these must be addressed to maximize the contributions of BHWs to the postpartum healthcare system.

Keywords: Barangay Health Worker (BHW), Health volunteer, Postpartum, Maternal health, Health system, Philippine

Introduction

The maternal mortality rate (MMR), or number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, in the Philippines was 170 in 1990, 120 in 2000, and 99 in 2010. Although this rate has undergone a slow decrease over time, it remains unacceptably high [1–3]. To improve the MMR, efforts in the Philippines have focused on pregnancy and delivery [4–7]. However, maternal death occurs, not exclusively at delivery, but also during the postpartum period [8–10]. Unfortunately, only 13.5% of postpartum women receive their first postpartum check-up in the 3–41 days after delivery, and 9.0% do not receive any check-ups [11, 12]. Interestingly, Singh et al. have demonstrated that the under-utilization of postpartum maternal healthcare services might explain why maternal mortality remains high among adolescent mothers in India [13]. In addition, Romeo et al. suggested that women should consistently obtain care and support from skilled providers in the Philippines, throughout the gestation, birth, and postpartum periods [14]. Therefore, the low level of maternal healthcare services that are provided to postpartum women by health centers may be responsible for the persistently high MMR in the Philippines. Previous studies have reported that the reasons for this reduced level of service includes economic factors, access to service, transportation issues, and permission from the patient’s family [15–19]. In addition, Yamashita et al. have reported that the majority of postpartum women have a poor overall understanding of postpartum health issues, especially profuse bleeding, postpartum depression, and increased blood pressure [20]. Furthermore, they reported that women who gave birth at home utilized postpartum healthcare services less than women who gave birth at medical centers.

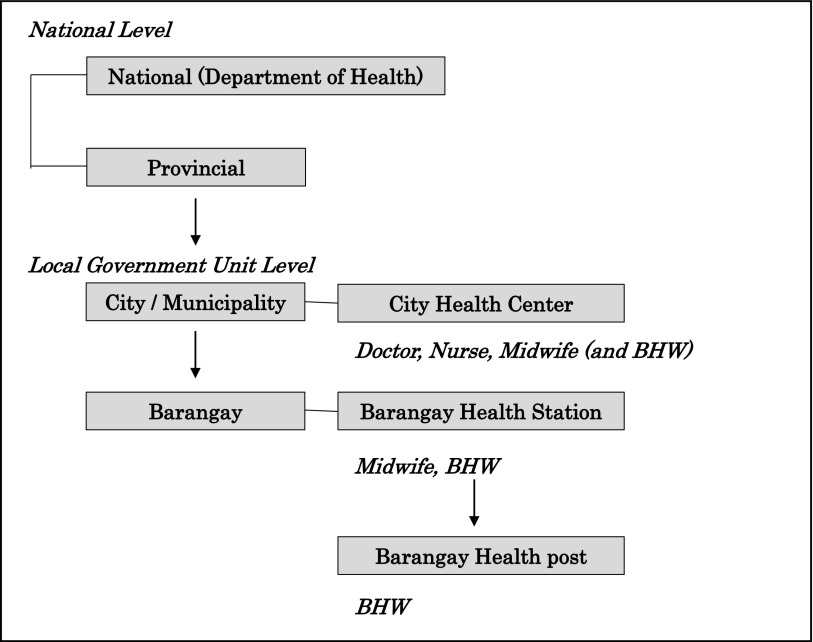

Unfortunately, the Philippines has a shortage of medical professionals who are qualified to evaluate the health of postpartum women in the community. However, there are health volunteers (“Barangay Health Workers”; BHWs) who work as assistants to nurses or midwives in the City Health Center, the Barangay Health Station, and the Barangay Health Post [4]. They are registered with the Local Government Unit, and work at the above facilities as part of the healthcare delivery system (Fig. 1). These workers are defined by the Republic Act (law 7883, approved on 20 February 1995 by the Department of Health) as “A person who voluntarily renders primary healthcare services in the community, in accordance with the guidelines promulgated by the Department of Health in the Philippines” [21–24]. Interestingly, several sources had reported that “BHWs, as key health providers in health service delivery, have been successfully implemented as public health programmers, but their potential contributions to scale up health services have yet to be fully tapped” [25, 26]. Yamashita et al. have also reported that they might be able to play an important role in educating postpartum women regarding the utilization of postpartum healthcare services [20]. It is important for BHWs to fully understand postpartum health care services and to be highly motivated in their activities. However, there are no studies that have examined these activities in the Philippines.

Fig. 1.

The healthcare delivery system in the Philippines and the role of Barangay Health Workers (BHWs).

Thus, we conducted a focus group interview (FGI) of BHWs regarding the postpartum healthcare services that they provided in Muntinlupa City, the Philippines. In this study, we evaluated the specific activities of BHWs, the problems they encountered in conducting these activities, and their reasons for choosing to work as a BHW.

Methods

A qualitative descriptive FGI method was used in this study. The FGI allowed us to obtain comprehensive and diverse data in a short period of time, and allowed us to investigate the BHW’s perceptions and their activities.

Setting

Muntinlupa City is located in the Luzon region of the Republic of the Philippines, neighboring the capital city (Manila). Muntinlupa City is divided into nine districts (barangays), with a total population of 487,376 (2013) [27]. In 2009, the total number of births in the Philippines was 2,245,000, and the fertility rate was 3.1 children per couple [28]. The total number of BHWs in Muntinlupa City is approximately 450.

Participants

The study target was subjects who had worked as a BHW for at least one year. Among the 450 BHWs who we approached in Muntinlupa City, we obtained informed consent from 13 BHWs, who were included in the study.

Interview

1) FGI

The FGI was conducted in a Muntinlupa City Hall conference room for approximately 90 min during January 2013, with the 13 participants and an interviewer (TY). To proceed with FGI, the interviewer firstly asked the participants’ characteristics (sex, age, educational background, BHW experience, child-rearing, number of professional seminars attended, and the motivation for attending the seminar). The interviewer also asked the participants the following questions: “What maternal and child health activities do you provide as a BHW?”, “During your home visits, what difficulties do you face in supporting your patients?”, and “What is the reason you continue to work as a BHW?” according to the interview guide, which is shown in Table 1. A lot of discussion focused on the three topics. The answers were then analyzed according to the interview guide, using a qualitative research method. The records of the FGI were translated from Tagalog to English by a Filipino translator.

Table 1.

Interview Guide

| Topics | |

|---|---|

| 1. | What maternal and child health activities do you provide as a BHW? |

| 2. | During your home visits, what challenges do you face in supporting your patients? |

| 3. | What is the reason you continue to work as a BHW? |

BHW: Barangay Health Worker

2) Data analyses

The proceedings of the FGI were transcribed verbatim, and constant comparative analyses were used to analyze the data [29, 30]. For these analyses, three researchers (TY, SAS, and HM) independently read and coded the focus group transcripts, based on the similarities and differences in the responses. The codes were then used to construct a primary coding framework and categories, and the reliability of this framework and categories was assessed. The trustworthiness of the data was confirmed by examining the data that has been reported in a wide range of literature [31, 32]. The researchers confirmed the reliability of the FGI analysis by re-checking the codes and categories.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Kobe University Graduate School of Health Sciences, as well as the Human Research Ethics Committee of Philippine General Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The participants’ characteristics are summarized in Table 2. All participants were women, with a mean age of 49.8 ± 5.9 years (mean ± SD). The participants’ educational background was classified into four categories: bachelor degree (38.5%), some college (30.8%), high school graduate (23.1%), and other (7.7%). The mean period of experience as a BHW was 7.2 ± 4.0 years, and all participants had experience in child rearing. The mean number of participants who had attended professional development seminars was 2.5 ± 2.0. Most participants reported being motivated to attend a seminar on postpartum care.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| ID | Age (years) | Education | BHW experience (years) | Seminars attended as a BHW (n) | Motivated to attend a seminar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | High school | 17 | 5 | + |

| 2 | 52 | High school | 4 | 5 | + |

| 3 | 43 | Bachelor | 4.5 | 1 | + |

| 4 | 49 | Bachelor | 15 | 0 | + |

| 5 | 58 | Bachelor | 6.5 | 5 | + |

| 6 | 56 | College | 5 | 2 | + |

| 7 | 40 | College | 6 | 1 | + |

| 8 | 44 | College | 4 | 2 | + |

| 9 | 44 | — | 4 | 0 | + |

| 10 | 57 | Bachelor | 6 | 3 | + |

| 11 | 45 | High school | 7 | 0 | − |

| 12 | 52 | Bachelor | 5 | 4 | + |

| 13 | 50 | College | 9 | 5 | + |

| Mean ± SD | 49.8 ± 5.9 | 7.2 ± 4.0 | 2.5 ± 2.0 | ||

ID: Participant identification number, SD: Standard deviation, BHW: Barangay Health Worker

Postpartum healthcare services

Following the interview guide, we evaluated the participants’ activities in providing postpartum healthcare services, the challenges that they encountered while providing home-visit services, and their motivation to continue their work (Table 3). These results are summarized in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Postpartum healthcare services provided by Barangay Health Workers (BHWs)

| Code | Category | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview Guide 1. Type of BHW activities | |||

| 1-1) | Ask about their vaginal bleeding | Assessment of postpartum women’s conditions | |

| 1-2) | Ask how they are | ||

| 1-3) | Ask about their well-being | ||

| 1-4) | Recommend that they visit a health center when they have pain or infection in the breast | Recommendation to visit a health facility | |

| 1-5) | Recommend that they visit a health center when they have bleeding or infection | ||

| 1-6) | Recommend that they visit a doctor when they feel pain in the breast during when breastfeeding | ||

| 1-7) | Recommend that they visit a health center when they have a wound or fever in the breast | ||

| 1-8) | Provide vitamin A | Measurement of blood-pressure and vitamin intake | |

| 1-9) | Measure blood pressure | ||

| 1-10) | Counseling regarding vaccination | Providing postpartum health information | |

| 1-11) | Provide health information | ||

| Interview Guide 2. Challenges in supporting patients | |||

| 2-1) | Our knowledge regarding postpartum care is not updated | No current information regarding postpartum care | |

| 2-2) | Our knowledge of postpartum care is insufficient, due to minimal training | ||

| 2-3) | We have a limited ability to acquire knowledge regarding postpartum care during work | ||

| 2-4) | Patients are stubborn and refuse healthcare services from BHWs | Some postpartum women do not want to receive health care services from a BHW | |

| 2-5) | BHWs have many patients, and there are few BHWs | Too many assigned postpartum women | |

| Interview Guide 3. Motivation to continue BHW work | |||

| 3-1) | We enjoy helping patients, especially poor patients | Hospitality to help postpartum women and their family in the community | |

| 3-2) | We want to help patients and their families | ||

| 3-3) | We want to promote postpartum healthcare services through our own activities | ||

| 3-4) | We enjoy our activities | Performance of mission in providing BHW services | |

| 3-5) | We love the BHW’s role | ||

Fig. 2.

A summary of Barangay Health Workers’ activities, challenges and motivations for providing postpartum healthcare services.

1) BHW’s postpartum healthcare activities

Four categories were highlighted from among eleven analysis codes: “Assessment of postpartum women’s conditions,” “Recommendation to visit a health facility,” “Measurement of blood-pressure and vitamin intake,” and “Providing postpartum health information.” The “Assessment of postpartum women’s conditions” category assessed the BHW’s evaluation of postpartum women’s health during home-visits, and consisted of code 1-1 (Ask about their vaginal bleeding), code 1-2 (Ask how they are), and code 1-3 (Ask about their well-being). The “Recommendation to visit a health facility” category evaluated the BHW’s recommendations to postpartum women with complicated illness, and consisted of code 1-4 (Recommend that they visit a health center when they have pain or infection in the breast), code 1-5 (Recommend that they visit a health center when they have bleeding or infection), code 1-6 (Recommend that they visit a doctor when they feel pain in the breast during breastfeeding), and code 1-7 (Recommend that they visit a health center when they have bleeding or fever in the breast). The “Measurement of blood-pressure and vitamin intake” category evaluated the BHWs’ ability to examine postpartum women, and consisted of code 1-8 (Provide vitamin A) and code 1-9 (Measure blood pressure). The “Providing postpartum health information” category evaluated the BHWs’ ability to manage postpartum physical and mental conditions, and consisted of code 1-10 (Counseling regarding vaccination) and code 1-11 (Providing information regarding health).

2) Difficulties encountered while providing home-visit services

Three categories were highlighted from among five analysis codes: “No current information regarding postpartum care,” “Some postpartum women do not want to receive healthcare services from a BHW,” and “Too many assigned postpartum women.” The “No current information regarding postpartum care” category consisted of code 2-1 (Our knowledge of postpartum care is not updated), code 2-2 (Our knowledge of postpartum care is insufficient, due to minimal training), and code 2-3 (Limited ability to acquire additional knowledge regarding postpartum care during their work). This category indicates that BHWs do not have the latest information, knowledge or skills regarding postpartum healthcare services. The “Some postpartum women do not want to receive healthcare services from a BHW” category consisted of code 2-4 (Patients are stubborn and refuse healthcare services from BHWs), and indicated that some patients do not respond well to BHWs. The “Too many assigned postpartum women” category consisted of code 2-5 (BHWs have many patients, and there are few BHWs), and indicated that BHWs have too many clients to care for.

3) Motivation to continue working as a BHW

Two categories were highlighted from among five analysis codes, which were defined as “Hospitality to help postpartum women and their families in the community” and “Performance of mission in providing BHW services.” The “Hospitality to help postpartum women and their families in the community” category consisted of code 3-1 (We enjoy helping patients, especially poor patients), code 3-2 (We want to help patients and their families), and code 3-3 (We want to promote postpartum healthcare services through our own activities). That category indicated that BHWs would like to support postpartum women and their families in the community. The “Performance of mission in providing BHW services” category consisted of code 3-4 (We enjoy our activities) and code 3-5 (We love the BHW’s role); this category indicates that BHWs enjoy their activities.

Discussion

This study, the first to evaluate BHWs’ activities in postpartum healthcare, indicated that BHWs play an important role in evaluating the physical and mental conditions of postpartum patients through home-visits. However, three major challenges affected their activities (“No current information regarding postpartum care,” “Some postpartum women do not want to receive healthcare services from BHW,” and “Too many assigned postpartum women”). Several sources also reported that “BHWs, as key health providers in health service delivery, have been successfully implemented as public health programmers, but their potential contributions to scale up health services have yet to be fully tapped” [25, 26]. Therefore, although BHWs can help improve postpartum maternal healthcare services in the Philippines, the above challenges must be resolved in order to fully maximize the BHWs’ contributions.

The main causes of maternal death in the Philippines are bleeding (17.9%), sepsis (8.0%), complications that occur at partum and in the postpartum period (41.0%), and pregnancy-induced hypertension (32.1%) [2]. However, maternal deaths can be prevented by the early detection of abnormalities, provision of health information, and recommendation to visit a health center. Our results indicate that the BHWs’ activities were “Assessment of postpartum women’s conditions,” “Recommendation to visit a health facility,” “Measurement of blood-pressure and vitamin intake,” and “Providing postpartum health information.” Therefore, it is possible that these activities may have helped reduce the MMR in the Philippines, although their effectiveness must be explored further. However, our results also indicate that the primary postpartum healthcare services that are provided by BHWs are important for enhancing the health of postpartum women and their families.

Unfortunately, we also detected three critical challenges that affect the postpartum healthcare services provided by BHWs. The first challenge was that some postpartum women did not want to receive healthcare services from a BHW, which may be caused by a lack of understanding regarding the BHW’s roles. Therefore, postpartum women and their families should be informed about the BHW’s roles and the related benefits. The second challenge was that BHWs support too many postpartum women and their families. Therefore, it might be useful to adjust the priority of BHWs’ home-visit services, based on the health of the postpartum women (e.g., from normal to high risk). Alternatively, the total number of BHWs might be increased to reduce each individual’s burden. The third challenge was that BHWs did not have the opportunity to acquire knowledge and skills regarding postpartum healthcare. However, we observed that BHWs are motivated to undergo further postpartum training. Therefore, various educational opportunities and programs should be prepared for BHWs by healthcare professionals.

Our study had three major limitations: the small sample size, the limited geographical area, and the lack of statistical analysis. However, this study was the first survey to identify current BHW activities, and the challenges that they face in providing postpartum healthcare services. Therefore, additional research is needed to confirm our results regarding the BHWs’ activities and their role in postpartum healthcare services in the Philippines.

In conclusion, we described the current activities and challenges that are encountered by BHWs while providing postpartum healthcare services in the Philippines. Through home-visit services, BHWs may play an important role in evaluating the physical and mental conditions of postpartum women. However, BHWs face several challenges regarding their knowledge, skills and ability to deliver health services. To address these challenges, patients must be informed regarding the BHWs’ role in the community, and educational initiatives for BHWs must be developed by healthcare professionals.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Muntinlupa City Health Center staff, Ms. Lorena Drapeza Rolando, Ms. Maria Paula Logdat, Ms. Mhadz Geronimo, Ms. Gwen Gagan-Denolan, Ms. Giecela Mae Hernando Taburnal (of the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program, the Philippines), and Ms. Kyoko Shimazawa (of the Kobe City College of Nursing, Japan). This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 24792581.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: TY, SAS, CL, MTRT, YT, and HM. Performed the experiments: TY, SAS, CL, YT, and HM. Data analysis: TY, SAS, and HM. Contributed materials and analytical tools: TY, SAS, CL, MTRT, YT, and HM. Drafted the manuscript: TY, SAS, CL, MTRT, YT, and HM.

References

- 1.WHO and Department of Health, Philippines. Health Service Delivery Profile, Philippines. 2012. Available: http://www.wpro.who.int/health_services/service_delivery_profile_philippines.pdf

- 2.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group . Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006; 368: 1189–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abou-Zahr CL. Antenatal care in developing countries: promise, achievements and missed opportunity. An analysis of trends, levels and differentials, 1990–2001. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. The Philippines Health System Review. 2011. Available: http://www.wpro.who.int/philippines/areas/health_systems/financing/philippines_health_system_review.pdf [accessed 10 September 2014]

- 5.Countdown Coverage Writing Group, Countdown to 2015 Core Group, Bryce J, et al. Countdown to 2015 for maternal, newborn, and child survival: the 2008 report on tracking coverage of interventions. Lancet 2008; 371: 1247–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda. Statistics and indicators for the post-2015 development agenda. 2013. Available: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/untaskteam_undf/UNTT_MonitoringReport.shtml [accessed 2 August 2014]

- 7.Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384: 980–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. 2012. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75411/1/9789241548502_eng.pdf?ua=1 [accessed 2 August 2014]

- 9.Zupan J. Perinatal mortality in developing countries. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2047–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li XF, Fortney JA, Kotelchuck M, et al. The postpartum period: the key to maternal mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1996; 54: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Statistics Office Manila, Philippines. Philippines 2008 national demographic and health survey. Available: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR224/FR224.pdf [accessed 25 May 2014]

- 12.Langlois EV, Miszkurka M, Ziegler D, et al. Protocol for a systematic review on inequalities in postnatal care services utilization in low- and middle-income countries. Syst Rev 2013; 2: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, Kumar A, Pranjali P. Utilization of maternal healthcare among adolescent mothers in urban India: evidence from DLHS-3. Peer J 2014; 2: e593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee RD, Abellera M, Triunfante C, et al. Utilization of maternal health care services among low-income Filipino women, with special reference to Bicol Region. Asia Pacific E-Journal of Health Social Science 2012; 1: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Titaley CR, Dibley MJ, Roberts CL. Factors associated with non-utilisation of postnatal care services in Indonesia. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009; 63: 827–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Titaley CR, Hunter CL, Heywood P, et al. Why don’t some women attend antenatal and postnatal care services? A qualitative study of community members’ perspectives in Garut, Sukabumi and Ciamis districts of West Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010; 10: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onah HE, Ikeako LC, Iloabachie GC. Factors associated with the use of maternity services in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63: 1870–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simkhada B, Teijlingen ER, Porter M, et al. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 2008; 61: 244–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakraborty N, Islam MA, Chowdhury RI, et al. Utilisation of postnatal care in Bangladesh: evidence from a longitudinal study. Health Soc Care Community 2002; 10: 492–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamashita T, Suplido SA, Ladines-Llave C, et al. A Cross-Sectional Analytic Study of Postpartum Health Care Service Utilization in the Philippines. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e85627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act 7883 - Brgy. Health Workers Benefits & Incentives Acts of 1995. Available: http://excell.csc.gov.ph/ELIGSPECIAL/ra7883.pdf [accessed 20 July 2014]

- 22.Maternal and Child Health Service Department of Health Philippines. Barangay Health Workers Training Manual. Available: http://library.doh.gov.ph/doh_publication/doh005/BARANGAY%20HEALTH%20WORKERS%20TRAINING%20MANUAL.pdf [accessed 12 June 2014].

- 23.Human Resources for Health: maternal, neonatal and reproductive health at community level. A profile of the Philippines. The University of New South Wales Human Resources For Health Knowledge Hub. Available: https://sphcm.med.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/sphcm/Centres_and_Units/MNRH_Philippines_Summary.pdf [accessed 10 September 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health, Philippines. Implementing Health Reforms Toward Rapid Reduction in Maternal and Neonatal Mortality. Manual of Operations. 2009. Available: http://www.doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/maternalneonatal.pdf [accessed 10 September 2014]

- 25.Lacuesta MC, Sarangani ST, Amoyen ND. A diagnostic study of the DOH health volunteer workers program. Philipp Popul J 1993; 9: 26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voluntary Service Overseas International. National volunteering health research report. Available: http://www.vsointernational.org/Images/Local_Volunteering_Responses_to_Healthcare_Challenges_tcm76-21052.pdf [accessed 30 January 2015]

- 27.Muntinlupa City’s Official Website. Available: http://www.muntinlupacity.gov.ph/index.php?target=about¶ms=request_._resord# [accessed 5 August 2014]

- 28.The National Statistical Coordination Board of the City of Muntinlupa. Available: http://www.nscb.gov.ph/activestats/psgc/municipality.asp?muncode=137603000®code=13&provcode=76 [accessed 20 July 2014]

- 29.Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C, Bryon E, et al. QUAGOL: a guide for qualitative data analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2012; 49: 360–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hewitt-Taylor J. Use of constant comparative analysis in qualitative research. Nurs Stand 2001; 15: 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lennie J. Increasing the rigour and trustworthiness of participatory evaluations: learnings from the field. Evaluation Journal of Australasia 2006; 6: 27–35. [Google Scholar]