Highlights

-

•

We examine the role of EGCG, a major polyphenol in green tea, in bone metabolism.

-

•

LPS is a pathogen-associated molecule, and induces inflammatory bone resorption.

-

•

EGCG suppresses the LPS-induced PGE production in osteoblasts.

-

•

EGCG suppresses the LPS-induced bone resorption of alveolar bones in vitro.

-

•

In the mouse model of periodontitis, EGCG restores the loss of alveolar bone mass.

Abbreviations: BMN, bone mineral density; COX, cyclo-oxygenase; EGCG, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; mPGES, membrane-bound PGE synthase; OCPC, o-cresolphthalein complexon; OPG, osteoprotegerin; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PSD, polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis; RANKL, receptor activator of NF-kB ligand

Keywords: Epigallocatechin gallate, Lipopolysaccharide, Bone resorption, Periodontitis, Prostaglandin E, Osteoblasts

Abstract

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a major polyphenol in green tea, possesses antioxidant properties and regulates various cell functions. Here, we examined the function of EGCG in inflammatory bone resorption. In calvarial organ cultures, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced bone resorption was clearly suppressed by EGCG. In osteoblasts, EGCG suppressed the LPS-induced expression of COX-2 and mPGES-1 mRNAs, as well as prostaglandin E2 production, and also suppressed RANKL expression, which is essential for osteoclast differentiation. LPS-induced bone resorption of mandibular alveolar bones was attenuated by EGCG in vitro, and the loss of mouse alveolar bone mass was inhibited by the catechin in vivo.

1. Introduction

In bone tissues, bone mass is regulated by bone resorption and bone formation, and bone resorption is elicited by osteoclasts differentiated from the macrophage lineage cells. Previous studies have identified the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL), also known as the osteoprotegerin (OPG) ligand [1–4], as a pivotal factor required for osteoclast differentiation. Osteoblasts express RANKL in response to bone-resorbing factors such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and IL-1, and interact with osteoclast precursors expressing RANK, inducing their differentiation into mature osteoclasts by a mechanism involving the RANK-RANKL interaction [3,4].

PGE2 is a typical mediator associated with inflammation, and is produced by various types of cells. In bone tissue, PGE2 is mainly produced by osteoblasts, and is one of the major inducers of RANK-dependent osteoclast differentiation and osteoclastic bone resorption [5]. Previous studies have shown that cyclo-oxygenases (COX)-2 and membrane-bound PGE synthase (mPGES)-1 are inducible enzymes that initiate PGE biosynthesis in various cells, including osteoblasts, after inflammatory stimuli [6,7]. We have reported that the bone resorption associated with inflammation was attenuated in mPGES-1-deficient mice (mPges1−/−) due to the lack of PGE production by osteoblasts [7]. Therefore, the PGE2 produced by osteoblasts is a critical regulator of bone metabolism.

Previous studies have shown that compounds in fruits and vegetables are beneficial to our health. Among these, polyphenols, including flavonoids, are known to exhibit physiological and pharmacological properties such as anti-oxidative, anti-bacterial and anti-tumor activities [8,9]. Isoflavones have been reported to show beneficial effects on the bone mass in vivo [10]. Catechins are major flavonoids naturally present in certain species of plants, including tea. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a major component of green tea catechins, has been reported to show the strongest effects among the catechins on various cell functions, and exhibits anti-oxidant and anti-tumor activity [8,9]. However, there have been only a few studies of the effects of EGCG on bone metabolism and skeletal health. Catechin is reported to enhance alkaline phosphatase activity in osteoblasts and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells [11,12], and EGCG inhibits osteoclastic differentiation from macrophage [13], but the effects of EGCG on inflammatory bone resorption are not known.

It is known that periodontitis is initiated by a synergistic and dysbiotic microbial community, and the recent pathological concept for reasoning of periodontal diseases is based on the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model [14], Periodontal plaque from the disease site induces inflammatory responses through Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation [15], and the simultaneous infection with P. gingivalis is also required. Our model for inflammatory bone resorption of alveolar bone is focused and mimicked on the periodontal bone resorption which is based on the TLR4-induced osteoclastgenesis in mice [7]. Using our model of the destruction of alveolar bone in vivo, we have reported that PGE2 is closely related to the LPS-induced alveolar bone resorption, since we detected LPS-induced alveolar bone resorption in wild-type mice, but not in mPGES-1-null mice [7]. Therefore, PGE2 production may play a key role in LPS-induced alveolar bone resorption via TLR4 in mice [7].

We examined the influence of EGCG on the calvarial bone resorption induced by LPS, and on the COX-2- and mPGES-1-dependent PGE synthesis in mouse osteoblasts. EGCG inhibited LPS-induced osteoclastic bone resorption by suppressing the PGE2 production by osteoblasts in vitro, and attenuated the inflammatory bone loss of the mouse mandibular alveolar bone in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and experimental reagents

Mice of ddy strain were obtained from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan), and animal experiments were performed under the institutional guidelines for animal research. LPS was obtained from Sigma Aldrich Co. LLC., MO, USA. EGCG was obtained from Nagara Science Corporation, Japan (Purity: more than 99%) for in vitro study, and from Taiyo Kagaku Co. Ltd. (Sunphenon EGCG-OP; Purity: more than 90%) for in vivo study.

2.2. Culture of primary mouse osteoblastic cells

Primary osteoblastic cells were isolated from newborn mouse calvariae after five routine sequential digestions with 0.1% collagenase (Roche Applied Science) and 0.2% dispase (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), as described previously [7]. Osteoblastic cells collected from fractions two to four were combined and cultured in α-modified MEM (αMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in air. After 24 h in culture, they were treated with LPS with and without EGCG, and further cultured for 24 h for measurement of PGE2.

2.3. Measurement of the PGE2 content

The concentrations of PGE2 in culture samples were calculated using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (GE Healthcare UK Ltd). The cross-reactivity of the antibody in the EIA was calculated as followed: PGE2, 100%; PGE1, 7.0%; 6-keto-PGF1α, 5.4%; PGF2α, 4.3% and PGD2, 1.0%.

2.4. Bone-resorbing activity in organ cultures of mouse calvaria

Calvariae were collected from newborn mice, dissected in half and cultured for 24 h in BGJb containing 1 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin (BSA). After 24 h, the calvaria were transferred to new medium with or without EGCG and with or without LPS, and were cultured for another five days. The concentration of calcium in the conditioned medium was measured by the o-cresolphthalein complexon (OCPC) method. The bone-resorbing activity was expressed as the increase in the medium calcium concentration.

2.5. Quantitative PCR analysis

Mouse osteoblastic cells were cultured for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h in αMEM containing 1% FCS with or without LPS and with or without EGCG, and total RNA and cDNA were prepared as shown in previous papers [5,7], and the quantitative-PCR (q-PCR) was performed. The primer pairs used in the q-PCR for the mouse RANKL, COX-1, COX-2, mPGES-1, mPGES-2 and cPGES genes were as follows: Mouse RANKL: 5′-AGGCTGGGCCAAGATCTCTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCTGTAGGTACGCTTCCCG-3′ (reverse), mouse COX-1: 5′-ACTGGTGGATGCCTTCTCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTCGGGACTCCTTGATGAC-3′ (reverse), mouse COX-2: 5′-GGGAGTCTGGAACATTGTGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGCACATTGTAAGTAGGTGGACT-3′ (reverse), mouse mPGES-1: 5′-GCACACTGCTGGTCATCAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACGTTTCAGCGCATCCTC-3′ (reverse), mouse mPGES-2: 5′-CGTGAGAAGGACTGAGATCAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGGAGTCATTGAGCTGTTGC-3′ (reverse), mouse cPGES: 5′-CGAATTTTGACCGTTTCTCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGAATCATCATCTGCTCCATCT-3′ (reverse). The cDNA of the respective genes was quantified by q-PCR with SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), and the results are shown as the relative expression compared with the control group (without LPS and EGCG) at 3 h.

2.6. Bone-resorbing activity of mouse mandibular alveolar bone in organ cultures

Mouse mandibular alveolar bone were collected from the molar region and three molars were removed under a microscope. The isolated alveolar bone were cultured for 24 h in BGJb containing 1 mg/ml BSA. After 24 h in the organ cultures, the alveolar bone was transferred to new media, with or without LPS and with or without EGCG, and was cultured for another five days. The bone-resorbing activity was determined by the increase in medium calcium compared to control culture [7].

2.7. Inflammatory bone loss of the mouse alveolar bone in vivo

In the model of experimental periodontitis, LPS (25 μg/mouse) was dissolved in 50 μL of PBS and injected into the outside of the lower gingiva of the mice on days 0, 2 and 4. As a control, PBS was injected into the lower gingiva at the same time points. After seven days of the first injection, the mandibular alveolar bones were collected from mouse molar region, and three molars were removed. The bone mineral density (BMD) of the total area of alveolar bone was measured by DEXA [7].

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test for post hoc analysis. All data are presented as the means ± SEM, and all statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Ver.23 software.

3. Results

3.1. EGCG recovers LPS-induced bone resorption in mouse calvarial organ cultures

Bone resorption is mediated by osteoclasts, and induces the loss of calcified bone tissue. Organ culture of mouse calvaria is a typical ex vivo assay system to define the effects of a test compound on bone resorption and bone loss, and all bone-resorbing factors are known to induce bone-resorbing activity in this type of model. Using ex vivo cultures, we observed that bone-resorbing activity was induced by adding bone resorbing factors, including LPS. Catechins are one of the major flavonoids present in plant materials, including tea. EGCG is a major component of green tea catechins (Fig. 1A), and shows the strongest effects among the known catechins on various cell functions. To examine the effects of EGCG on inflammatory bone resorption, we added EGCG with or without LPS in the mouse calvarial ex vivo cultures. LPS markedly induced bone-resorbing activity, and EGCG recovered the bone resorption in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). EGCG did not show any effects on the bone-resorbing activity in the absence of LPS.

Fig. 1.

The chemical structure of EGCG, and the effects of EGCG on the LPS-induced bone-resorbing activity in organ cultures of mouse calvariae. (A) The chemical structure of EGCG. (B) Mouse calvariae were cultured for 24 h in BGJb containing 1 mg/ml of BSA. After 24 h, the calvariae were transferred to new media, and were cultured for five days with or without 1 μg/ml of LPS and with or without EGCG (30, 60 or 90 μM). The concentration of calcium in the medium was measured to calculate the bone-resorbing activity. The data are expressed as the means ± SEM of four to 10 independent wells. A significant difference between the two groups was indicated by: ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. control, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ##p < 0.001 vs. LPS.

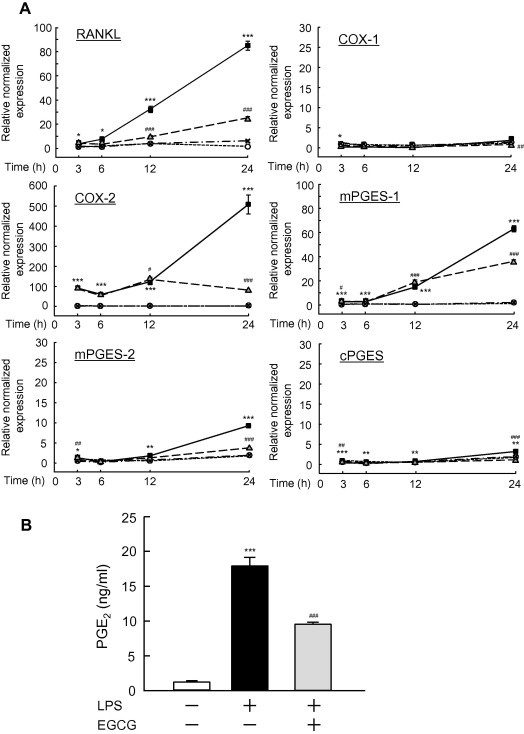

3.2. Effects of EGCG on PGE2 and PGE-related molecules in osteoblasts

We next performed q-PCR to examine the effects of EGCG on the mRNA expression of PGE-related genes such as COX-1, COX-2, mPGES-1, mPGES-2, and cPGES, and osteoclast-related gene RANKL in mouse osteoblasts. LPS markedly induced the mRNA expression of COX-2, mPGES-1 and mPGES-2 in osteoblasts after 12–24 h of exposure to LPS, and adding EGCG with the LPS clearly suppressed the LPS-induced expression of these mRNAs (Fig. 2A). LPS did not induce the expression of COX-1 or cPGES mRNA, and EGCG itself also did not influence the expression of these genes. EGCG suppressed the LPS-induced expression of RANKL mRNA in osteoblasts at 12–24 h, indicating that EGCG suppresses osteoclastic bone resorption by inhibiting the expression of RANKL in osteoblasts. In the cultures of osteoblasts, LPS induced the production of PGE2, and EGCG suppressed this PGE2 production induced by LPS (Fig. 2B). Therefore, EGCG acts on osteoblasts to suppress PGE2 production by negatively regulating COX-2, mPGES-1 and mPGES-2. The suppressive effects of EGCG on bone resorption may be elicited by the down-regulation of PGE biosynthesis in osteoblasts.

Fig. 2.

The effects of EGCG on the LPS-induced expression of COX-1, COX-2, mPGES-1, mPGES-2, cPGES and RANKL mRNA, and on the production of PGE2 in mouse primary osteoblasts. (A) Mouse osteoblasts were treated with 1 ng/ml of LPS with or without 30 μM EGCG for 3, 6, 12 or 24 h, and the total RNA was extracted. The mRNA expression levels of COX-1, COX-2, mPGES-1, mPGES-2, cPGES and RANKL were detected by q-PCR. The relative normalized expression was calculated by the determining the respective data for control cultures without LPS and EGCG at 3 h. The treatment groups were indicated as: control (○), LPS (■), LPS plus EGCG (△) and EGCG (X). The data are expressed as the means ± SEM of three independent wells. A significant difference between the two groups is indicated as: ∗p < 0.05,∗∗p < 0.01,∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. control, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. LPS. (B) Mouse osteoblasts were treated with 10 ng/ml of LPS with or without 30 μM EGCG for 24 h, and the levels of PGE2 were measured using the conditioned media. The data are expressed as the means ± SEM of four independent wells. A significant difference between the two groups is indicated as: ∗∗∗p < 0.001 vs. control, ###p < 0.001 vs. LPS.

3.3. Effects of EGCG on LPS-induced bone resorption in mouse mandibular alveolar bone

Using an organ culture system of mouse mandibular alveolar bone, we examined the effects of EGCG on bone resorption induced by LPS. The alveolar bones were collected from mouse lower mandibles (Fig. 3A), and were cultured with or without LPS. Bone resorbing activity was measured by the increase in medium calcium as shown in the section of Materials and Methods. LPS markedly induced the bone resorbing activity in organ cultures of alveolar bone, and adding EGCG clearly suppressed the resorption of alveolar bone (Fig. 3B). EGCG did not influence the alveolar bone resorption in cultures without LPS.

Fig. 3.

The effects of EGCG on LPS-induced bone resorption in organ cultures of mouse mandibular alveolar bone. (A) Mandibular alveolar bone specimens were collected from the molar region of the lower jaw under a microscope, and three molars were removed. (B) The collected mandibular alveolar bones were cultured for five days with EGCG (30, 60 or 90 μM) with or without LPS (1 μg/ml). The concentration of calcium in the medium was measured, and the increase in medium calcium was calculated as the bone-resorbing activity. The data are expressed as the means ± SEM of four independent wells. Significant differences are indicated by: ∗∗p < 0.01 vs. control. ##p < 0.01, vs. LPS.

3.4. EGCG inhibits LPS-induced alveolar bone loss in mice

To define the effects of EGCG on experimental model of bone loss of alveolar bone, we injected LPS with or without EGCG into the gingiva of the lower mandibles of mice. After seven days of the first injection, alveolar bone was collected from mouse, and the BMD was measured by DEXA. In this model, LPS markedly decreased BMD of the mandibular alveolar bone, while the simultaneous injection of EGCG significantly inhibited the LPS-induced loss of BMD in mice (Fig. 4). The injection of EGCG without LPS did not influence the BMD of the mandibular alveolar bone in mice, and the BMD was similar to that of control (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The administration of EGCG inhibited the LPS-induced loss of mandibular alveolar bone in mice. As a model for experimental periodontitis, LPS (25 μg/mouse) was injected into the mouse lower gingiva on days 0, 2 and 4. As a control, PBS was injected into the lower gingiva at each time point. EGCG (0.5 mg/mouse) was injected into the mouse lower gingiva with or without LPS in some animals. The mandibular alveolar bone was collected seven days after the first injection, and the BMD of the mandibular alveolar bones was measured. The data are expressed as the means ± SEM of 11–12 mice. A significant difference between the two groups is indicated by: ∗∗p < 0.01 vs. control, #P < 0.05, vs. LPS.

4. Discussion

Green tea is one of the most popular beverages in the world. In epidemiological studies, the consumption of green tea has been found to be associated with various benefits, such as a reduced risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease [8,16]. EGCG is a major component of the green tea catechins, and has been reported to show the strongest effects among the different catechins on various cell functions, and to exhibit anti-oxidant and anti-tumor activity [8,9]. However, the roles of EGCG in bone tissues are controversial, and the effects of EGCG on inflammatory bone resorption are not known. In the present study, EGCG suppressed the inflammatory bone resorption induced by LPS in mouse calvarial ex vivo cultures.

We found that EGCG acts on osteoblasts to suppress the LPS-induced PGE2 production by inhibiting the expression of COX-2, mPGES-1 and mPGES-2. EGCG also suppressed the expression of RANKL in osteoblasts. The RANKL expressed on the cell surface of osteoblasts is a key molecule required for osteoclast differentiation, and the factors that suppress RANKL, such as OPG and antibodies against RANKL, clearly suppressed osteoclastic bone resorption. Therefore, EGCG may act on the osteoblasts in bone tissues and suppress the bone resorption associated with inflammation via mechanisms involving both PGE synthesis and RANKL expression in osteoblasts.

Bone marrow macrophages are known to express RANK, and osteoclasts are differentiated from the monocyte–macrophage lineage by the RANK-RANKL interaction. In addition to osteoblasts, macrophages may also be target cells for EGCG. Lin et al. [13] reported that EGCG acts on RAW264.7 macrophages and inhibits their differentiation into osteoclasts. We also detected suppressive effects of EGCG on the soluble RANKL-dependent differentiation of mouse bone marrow macrophages into osteoclastic cells (data not shown). Therefore, the action of EGCG on macrophages may partially contribute to the suppressive effects of EGCG on bone resorption.

It is well known that Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play key roles in innate immunity, and several TLRs, TLR1-TLR13, were identified [17]. The ligands for respective TLR stimulate signal transduction in the target cells and regulate the host defense system against pathogens [17]. LPS is an outer membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria, and acts as a ligand for TLR4 expressed on cell surface of target cells. We previously reported that mouse osteoblasts express TLR4 and LPS-TLR4 signaling induces severe bone resorption associated with inflammation [7]. We also reported that mPGES-1-deficient mice are resistant to both LPS-induced osteoclast formation and LPS-induced PGE2 production in osteoblasts [7]. Therefore, PGE biosynthesis is essential for the effects of LPS on bone tissues. In the present study, EGCG suppressed the LPS-induced expression of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in osteoblasts. It may therefore be possible that EGCG interferes with the signal transduction of TLR4 in osteoblasts. The mechanism of action of EGCG in LPS-induced and TLR4-mediated PGE biosynthesis in osteoblasts is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

In periodontal diseases, the accumulation of bacterial plaque is commonly found in the periodontal pocket with the tooth surface located in the junction between gingiva and tooth. Periodontitis is a disease associated with bone destruction, and the bacterial LPS is thought to be pathogenic in the periodontal tissues. To examine the LPS-induced alveolar bone loss in periodontitis, we established a mouse organ culture system using mouse mandibular alveolar bone, and an in vivo model of alveolar bone loss by detecting the BMD of alveolar bone in mice [7,18]. Using the model, we reported that polymethoxy flavonoids, nobiletin and tangeretin, prevented LPS-induced inflammatory bone loss [19]. In the present study, we showed that EGCG suppressed the alveolar bone resorption induced by LPS in vitro, and inhibited the alveolar bone loss induced by LPS in vivo. Effective dosage of EGCG in vitro and in vivo shown in Figs. 3 and 4 were similar to those of polymethoxy flavonoids such as nobiletin [19]. A recent study suggested a possible role of green tea catechins in preventing periodontal infection [20,21]. When rats were orally treated with EGCG, the ligature-induced periodontitis was suppressed by EGCG, measured by loss of attachment, alveolar bone resorption and inflammatory cytokine expression [20], suggesting systemic administration of EGCG may have a therapeutic effects of damaged periodontal tissue. Yoshinaga et al. reported that the topical application of green tea extract with LPS suppressed LPS-induced periodontitis detected by loss of attachment with alveolar bone and inflammatory cell infiltration in rats [21], but it is not known which catechin is effective in the local periodontal tissues. In the present study, we directly showed the anti-resorption effects of EGCG on mouse alveolar bone, and suggested that EGCG is effective for preventing periodontitis by local treatment in periodontal tissues, but further studies are needed to define the role of EGCG in the pathogenesis of human periodontitis. Since EGCG is a major polyphenol in green tea, one of the most popular beverages consumed worldwide, it might be useful to perform a human study examining the intake of green tea on periodontal disease in order to further understand the possible roles of green tea catechins for the prevention and/or treatment of periodontitis.

Acknowledgments

TT, CM and MI conceived and designed the project, TT, CM, KW and MH acquired the data, all authors analyzed the data, TT, FG, CM and MI wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Anderson D.M., Maraskovsky E., Billingsley W.L., Dougall W.C., Tometsko M.E., Roux E.R., Teepe M.C., DuBose R.F., Cosman D., Galibert L. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature. 1997;390:175–179. doi: 10.1038/36593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasuda H., Shima N., Nakagawa N., Yamaguchi K., Kinosaki M., Mochizuki S., Tomoyasu A., Yano K., Goto M., Murakami A., Tsuda E., Morinaga T., Higashio K., Udagawa N., Takahashi N., Suda T. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacey D.L., Timms E., Tan H.L., Kelley M.J., Dunstan C.R., Burgess T., Elliott R., Colombero A., Elliott G., Scully S., Hsu H., Sullivan J., Hawkins N., Davy E., Capparelli C., Eli A., Qian Y.X., Kaufman S., Sarosi I., Shalhoub V., Senaldi G., Guo J., Delaney J., Boyle W.J. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suda T., Takahashi N., Udagawa N., Jimi E., Gillespie M.T., Martin T.J. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocr. Rev. 1999;20:345–357. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyaura C., Inada M., Suzawa T., Sugimoto Y., Ushikubi F., Ichikawa A., Narumiya S., Suda T. Impaired bone resorption to prostaglandin E2 in prostaglandin E receptor EP4-knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19819–19823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murakami M., Naraba H., Tanioka T., Semmyo N., Nakatani Y., Kojima F., Ikeda T., Fueki M., Ueno A., Oh S., Kudo I. Regulation of prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis by inducible membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase that acts in concert with cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32783–32792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inada M., Matsumoto C., Uematsu S., Akira S., Miyaura C. Membrane-bound prostaglandin E synthase-1-mediated prostaglandin E2 production by osteoblast plays a critical role in lipopolysaccharide-induced bone loss associated with inflammation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:1879–1885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang C.S., Maliakal P., Meng X. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by tea. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:25–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082101.154309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bors W., Saran M. Radical scavenging by flavonoid antioxidants. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1987;2:289–294. doi: 10.3109/10715768709065294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castelo-Branco C., Soveral I. Phytoestrogens and bone health at different reproductive stages. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2013;29:735–743. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2013.801441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vali B., Rao L.G., El-Sohemy A. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate increases the formation of mineralized bone nodules by human osteoblast-like cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2007;18:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin P., Wu H., Xu G., Zheng L., Zhao J. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) as a pro-osteogenic agent to enhance osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow: an in vitro study. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;356:381–390. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1797-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin R.W., Chen C.H., Wang Y.H., Ho M.L., Hung S.H., Chen I.S., Wang G.J. (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate inhibition of osteoclastic differentiation via NF-kappaB. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;379:1033–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajishengallis G., Lamont R.J. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshioka H., Yoshimura A., Kaneko T., Golenbock D.T., Hara Y. Analysis of the activity to induce toll-like receptor (TLR)2- and TLR4-mediated stimulation of supragingival plaque. J. Periodontol. 2008;79:920–938. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islam M.A. Cardiovascular effects of green tea catechins: progress and promise. Recent Pat. Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2012;7:88–99. doi: 10.2174/157489012801227292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawai T., Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto C., Oda T., Yokoyama S., Tominari T., Hirata M., Miyaura C., Inada M. Toll-like receptor 2 heterodimers, TLR2/6 and TLR2/1 induce prostaglandin E production by osteoblasts, osteoclast formation and inflammatory periodontitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;428:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tominari T., Hirata M., Matsumoto C., Inada M., Miyaura C. Polymethoxy flavonoids, nobiletin and tangeretin, prevent lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory bone loss in an experimental model for periodontitis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;119:390–394. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11188sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho A.R., Kim J.H., Lee D.E., Lee J.S., Jung U.W., Bak E.J., Yoo Y.J., Chung W.G., Choi S.H. The effect of orally administered epigallocatechin-3-gallate on ligature-induced periodontitis in rats. J. Periodontal. Res. 2013;48:781–789. doi: 10.1111/jre.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshinaga Y., Ukai T., Nakatsu S., Kuramoto A., Nagano F., Yoshinaga M., Montenegro J.L., Shiraishi C., Hara Y. Green tea extract inhibits the onset of periodontal destruction in rat experimental periodontitis. J. Periodontal. Res. 2014;49:652–659. doi: 10.1111/jre.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]