Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in non-cirrhotic livers is an uncommon finding and can present insidiously in patients. Another uncommon finding in HCC, and one of poor prognosis, is the presence of paraneoplastic diseases such as hypercalcemia. We report a case of a 66-year-old previous healthy Filipina woman who after routine laboratory evaluation was discovered to have hypercalcemia as the first sign of an advanced HCC without underlying cirrhosis. Because of the patient's relative lack of symptoms, healthy liver function, lack of classical HCC risk factors, and unexpected hypercalcemia, the diagnosis of a paraneoplastic syndrome caused by a noncirrhotic HCC was unanticipated.

Methods

Case Analysis with Pubmed literature review.

Results

It is unknown how often hypercalcemia is found in association with HCC in a non-cirrhotic liver. However, paraneoplastic manifestations of HCC, particularly hypercalcemia, can be correlated with poor prognosis. For this patient, initial management included attempts to lower calcium levels via zoledronate, which wasn't completely effective. Tumor resection was then attempted however the patient expired due to complications from advanced tumor size.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia of malignancy can be found in association with non-cirrhotic HCC and should be considered on the differential diagnosis during clinical work-up.

Keywords: humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy, non-cirrhotic liver, hepatocellular carcinoma, paraneoplastic syndrome, bisphosphonate

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HHM, hypercalcemia of malignancy; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone related peptide

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is estimated to be the fourth most common cancer globally. In the United States alone, an approximated 33,000 new cases will be diagnosed in 2014 with men outnumbering women by a ratio of two to one.1,2 Nearly 80–90% of cases of HCC are due to underlying cirrhosis caused by well-known risk factors such as chronic hepatitis B or C, alcoholism, alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).2,3 One large prospective case series found cryptogenic cirrhosis to be the second most common background liver disease in a cohort of 105 HCC patients, accounting for 29% of cases studied. Half of these patients had either histologically diagnosed Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatits by prior biopsy or clinical features of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (BMI >30, diabetes mellitus, or hypertriglyceridemia).4 While significantly less common, non-cirrhotic HCC still accounts for an unknown number of total cases. In fact, one large multicenter study in Italy demonstrated out of 3000 cases of HCC merely 52 patients, or <2% of cases, were due to non-cirrhotic HCC.5 Other sources estimate non-cirrhotic HCC to account for 20% of all cases world-wide.6 While the pathogenesis of HCC in patients with cirrhotic disease results from stepwise mutations, the disease progression of non-cirrhotic disease is still somewhat obscure and is possibly due to de novo carcinogenesis.6 Spontaneous neoplastic transformation may also result from exposure to genotoxins (e.g. aspergillus) or other underlying metabolic diseases such as glycogen storage disease.3,6

HCC is occasionally associated with paraneoplastic syndromes, albeit at a low frequency. HCC has reported associations with hypoglycemia,7 demyelination,8 pemphigus vulgaris,9 thrombocytosis,10–14 hypercalcemia,11–14 hypercholesterolemia,11–15 and erythrocytosis.11–14,16 The association between paraneoplastic syndromes and non-cirrhotic HCC is uncertain. We present a case describing humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy (HHM) as the first sign of an underlying HCC in an asymptomatic woman with a non-cirrhotic liver.

Methods

We conducted an internet-based literature search via Pubmed with key words, “hypercalcemia, paraneoplastic syndrome, hepatocellular carcinoma” on 11/21/14. Clinical, pathological, radiologic data and follow up information is reported.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old Filipina woman with no prior medical problems presented to her primary care physician for routine annual physical exam at which time she reported an unintentional ten-pound weight loss. The patient had no history of smoking or alcohol use, and no known family history of cancer. Physical exam was remarkable only for the stigmata of recent weight loss. However, laboratory results revealed elevated calcium 13.2 mg/dL (normal range 8.5–10.2), calcitriol 89 μg/mL (18–72), alkaline phosphatase 194 U/L (33–130), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 57 U/L (10–35). Albumin and bilirubin were within normal limits. The patient denied any excess intake of antacids or vitamins A and D, and was not taking any other prescribed medications.

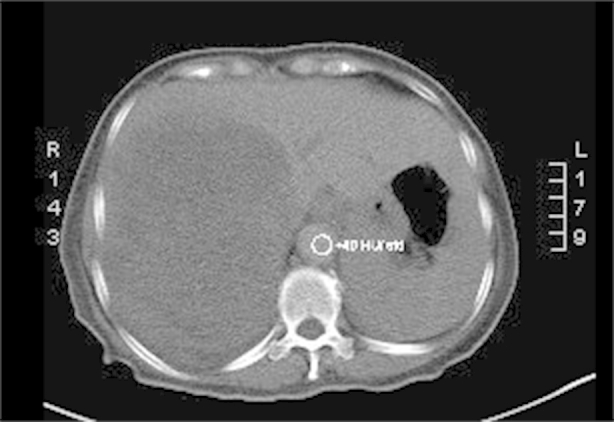

Follow-up renal sonogram to detect a renal origin of the hypercalcemia incidentally revealed a sizeable hepatic mass of 14.4 × 14.9 × 13.9 cm, prompting an abdominal MRI which demonstrated a 14.0 cm × 10.2 cm × 13.5 cm solid mass occupying the right lobe of the liver compressing the inferior vena cava and displacing the right hepatic vein. Follow-up computerized tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) found similar measurements for the primary liver lesion and demonstrated hepatic arterial enhancement with washout in the venous phase consistent with HCC. The follow-up CT scan also identified a small, irregular, spiculated lesion in the upper lobe of her right lung suspicious for a primary lung cancer.

Figure 1.

Baseline CT of patient showing large tumor in the right lobe of her liver.

Additional laboratory testing showed normal level of parathyroid hormone (PTH) 11 pg/dL (10–55) with an elevated level of parathyroid related peptide (PTHrp) 4.6 pg/dL (<2) and calcium of 12 mg/dl. Furthermore, tumor markers including Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) were 18.0 ng/dL (<10), Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) 3.0 ng/mL (<2.5) and Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) 131.1 U/mL (<37) were measured. Viral hepatitis serologies including hepatitis B serologies (surface antigen, surface antibody, and core antibody) and hepatitis C antibody were confirmed to be negative.

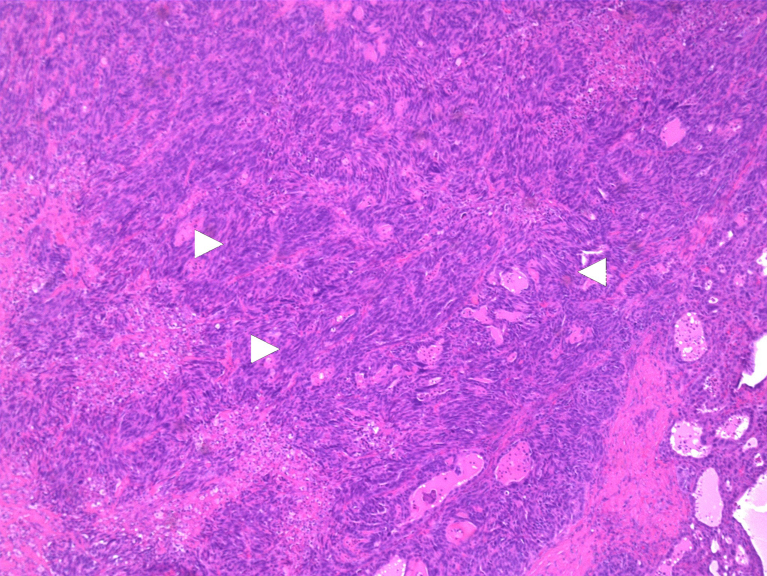

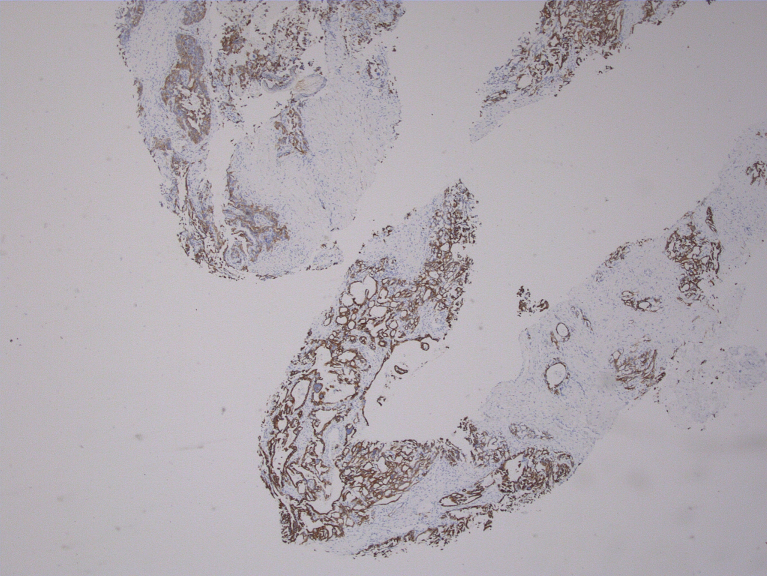

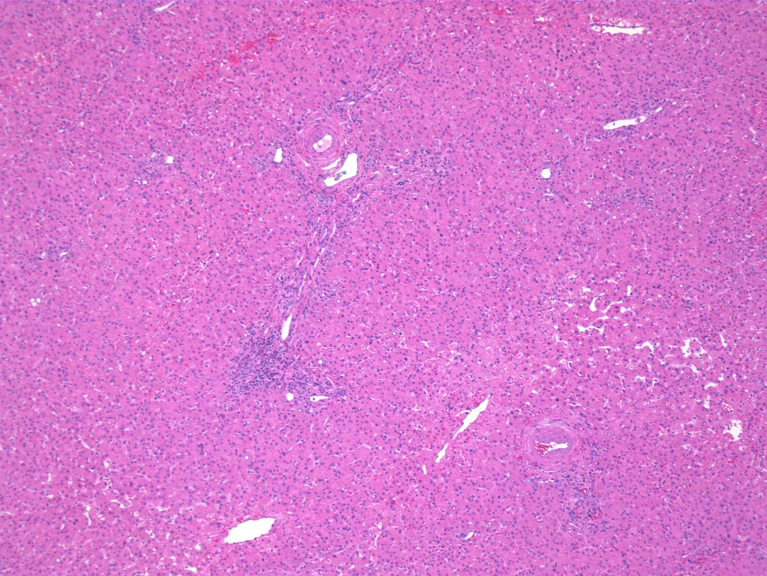

The initial diagnostic suspicion was that this patient had experienced humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy due to a primary lung neoplasm with an additional primary neoplasm of the liver. Subsequent biopsy of the spiculated lung nodule demonstrated a 1.7 cm granuloma, ruling out a lung neoplasm. A CT-guided liver biopsy diagnosed HCC by performing an immunohistochemistry assay which was positive for Hep-par1(liver specific), glypican-3(HCC sensitive and specific) and CK-7(positive in 9–18% HCC). The stains were negative for other markers notably CK20, S100p, TTF-1 and Napsin-A. Analysis of the biopsy performed at 100× magnification and demonstrates poorly differentiated and disorganized morphology with numerous elongated spindled cells (Figure 2). A glypican-3 stain, specific for HCC, is shown at 40× to be positive on the biopsy (Figure 3). These biopsy results suggested that the HHM was a manifestation of HCC. Her physicians began treatment with 4 mg/dL of IV zoledronic acid, a bisphosphonate that is effective in lessening hypercalcemia, in addition to hydration with 1 L of normal saline. One week later, her calcium was at a nadir of 11.3 mg/dL but merely two days after was at 11.9 mg/dL. She was then given 20 mg of furosemide along with another liter of normal saline. Her calcium over a span of two weeks lessened to 11.3 following treatment. Prior to hepatic resection, a CT-guided biopsy of the left lobe of the liver was done to ensure healthy parenchyma without evidence of cirrhosis. This biopsy, taken from the left lobe, and analyzed at 100× magnification shows healthy, normal non-cirrhotic hepatic tissue (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Hemotoxylin and Eosin stain from tumor biopsy demonstrating spindled cells (white arrowheads) and a poorly differentiated disorganized tumor at 100× magnification.

Figure 3.

Positive Glypican-3 stain shown at 40×.

Figure 4.

Hemotoxylin and Eosin stain from biopsy of uninvolved left lobe of the liver showing normal, non-cirrhotic healthy liver tissue at 100× magnification.

The tumor was locally advanced and encased the infrahepatic inferior vena cava. An attempt was made at surgical resection by resection of the right liver with en bloc resection of the vena cava and reconstruction. Although the tumor was successfully resected, the patient expired intraoperatively from complications related to bleeding and hypotension shortly after. Subsequent histopathologic analysis was performed on the sample and was consistent with the core biopsy diagnosis of HCC.

Discussion

Non-cirrhotic HCC can present with symptoms such as malaise, anorexia, and fatigue but not necessarily.4 In fact, due to the relative lack of symptoms patients with non-cirrhotic HCC have an insidious progression of disease, resulting in delayed detection. This delay in diagnosis is often why such patients have larger tumor burdens at initial presentation with an average of 12 cm compared to cirrhotic HCC with variable but often smaller sizes.5

Current clinical evidence suggests that the first step of management for patients who have preserved hepatic function (Childs-Pugh score A) and a solitary mass is resection.17 Despite preserved liver function, patients with non-cirrhotic HCC do not have significantly higher rates of survival than do patients with cirrhotic HCC. While there is decreased risk of liver decompensation following a hepatectomy in a non-cirrhotic HCC the mortality rates are relatively comparable to cirrhotic patients due to advanced tumor burden at presentation.18–20 While the post resection five-year survival rates for a non-cirrhotic liver (44–58%) remain higher than survival post resection for a cirrhotic liver (23–48%), the prognosis remains dismal.5 Despite this patient's Childs-Pugh score of A, she died due to surgical complications caused by the extensive size of the tumor.

Both the finding of non-cirrhotic HCC and HHM are unusual in this case. Most patients with HHM tend to display profound and obvious symptoms; most commonly neurological.21 In our case, the patient had no clear signs or symptoms of hypercalcemia, possibly suggesting a slow onset of her disease.

Studies have investigated both the prevalence and prognosis of different paraneoplastic diseases found in HCC (Table 1). As demonstrated in Table 1, hypercalcemia can be found in 4–8% of HCC tumors. When HCC causes paraneoplastic manifestations, it tends to indicate a poor prognosis.11–13 A study by Luo et al evaluating 903 patients found that 179 patients had paraneoplastic syndromes with HCC. After controlling for age, sex, and tumor volume a second group of 179 patients without paraneoplastic disease was selected. Survival at 9 months was 28% in patients without paraneoplastic diseases compared to 10% in those with paraneoplastic diseases suggesting a negative prognosis.14 In addition, Chang et al studied 457 patients and demonstrated the presence of hypercalcemia had a hazard ratio of 1.76 (P = 0.012) on univariate analysis making it a significant negative prognostic factor.11 Interestingly, none of these studies delineate which patients had cirrhotic versus non-cirrhotic HCC making the association between HHM in non-cirrhotic HCC unknown.

Table 1.

Literature review of prevalence and prognosis of paraneoplastic diseases in HCC.

| Author/Year | Total number of patients (n) | Paraneoplastic syndrome (Percentage of cohort; Median survival) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypercalcemia | Erthrocytosis | Hypercholestrolemia | Hypoglycemia | Median PNS; Non PNS Overall survival | ||

| Luo, 2002 | n = 903 | 4.5%; 15 days | 2.3%; 300 days | 12.7%; 28 days | 5.6%; 55 days | 118 days; NRa |

| Luo, 1999 | n = 1197 | 4.1%; NRa | 3.1%; NRa | 12.7%; NRa | 5.3%; NRa | 152 days; 634 days |

| Chang, 2013 | n = 457 | 5.3%; 8.4 weeks | 3.9%; 18 weeks | 24%; 12.9 weeks | NR; NRa | 12.4 weeks; 18.4 weeks |

| Qu, 2014 | n = 175 | 8%; 1.762 HRb | 8.1%; NRa | 23.2%; 1.32 HR | 13.1%; NRa | 15 months; 55 months |

NR: not reported.

HR: hazard ratio.

The management of HHM is also important. A review by Stewart reports that for patient with moderate HHM (12–13.9 mg/dL) the first line treatment is a bisphosphonate which should bring the level into the normal range within 4–7 days.21 Interestingly within 7 days her calcium did lower to 11.2 mg/dL however it was still elevated and rose within two days to 11.9. Stewart emphasizes that zoledronate is highly effective and should it not work then other regimens aimed at lowering calcium such as furosemide should be pursued.21 Whether her bisphosphonate resistant hypercalcemia speaks to the high tumor burden or specific tumor biology is uncertain. Either way aggressive monitoring for neurologic or cardiovascular symptoms is crucial.

Conclusion

This patient's atypical presentation of HCC did not bring her case to early clinical attention and made the diagnosis difficult for her clinicians. The patient's high level of calcium without accompanying symptoms demonstrates the potentially surreptitious nature of HHM. Although unusual, non-cirrhotic HCC can present late in disease progression with isolated hypercalcemia and therefore HCC should receive appropriate consideration on the differential diagnosis in a hypercalcemic patient.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2014. Cancer Facts and Figures 2014. Accessed 11.11.14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag H.B. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trevisani F., Frigerio M., Santi V., Grignas-chi A., Bernardi M. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: a reappraisal. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrero J.A., Fontana R.J., Su G.L., Conjeevaram H.S., Emick D.M., Lok A.S. NAFLD may be a common underlying liver disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:1349–1354. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giannini E.G., Marenco S., Bruzzone L. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients without cirrhosis in Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaddikeri S., McNeeley M.F., Wang C.L. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the noncirrhotic liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:34–47. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorlini M., Benini F., Cravarezza P., Romanelli G. Hypoglycemia, an atypical early sign of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2010;41:209–211. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walcher J., Witter T., Rupprecht H.D. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with paraneoplastic demyelinating polyneuropathy and PR3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:364–365. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200210000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinterhuber G., Drach J., Riedl E. Paraneoplastic pemphigus in association with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:538–540. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang S.J., Luo J.C., Li C.P. Thrombocytosis: a paraneoplastic syndrome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2472–2477. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang P.E., Ong W.C., Lui H.F., Tan C.K. Epidemiology and prognosis of paraneoplastic syndromes in hepatocellular carcinoma. ISRN Oncol. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2013/684026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/684026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qu Q., Wang S., Chen S., Zhou L., Rui J.A. Prognostic role and significance of paraneoplastic syndromes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am Surg. 2014;80:191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo J.C., Hwang S.J., Wu J.C. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with paraneoplastic syndromes. Hepato-gastroenterol. 2002;49:1315–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo J.C., Hwang S.J., Wu J.C. Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer. 1999;86:799–804. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990901)86:5<799::aid-cncr15>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tso S.C., Hua A.S.P. Erythrocytosis in hepatocellular carcinoma: a compensatory phenomenon. Br J Haematol. 1974;28:497–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1974.tb06668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inomata E., Sohda T., Nakane H. A case of hepatocellular carcinoma with paraneoplastic hypercholesterolemia, thrombocytosis and hypoglycemia. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;104:1231–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cillo U., Vitale A., Grigoletto F. Prospective validation of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system. J Hepatol. 2006;44:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nzeako U.C., Goodman Z.D., Ishak K.G. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic livers. A clinico-histopathologic study of 804 North American patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:65–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/105.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuart K.E., Anand A.J., Jenkin R.L. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Prognostic features, treatment outcome, and survival. Cancer. 1996;77:2217–2222. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2217::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroffolini T., Andreone P., Andriulli A. Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy. J Hepatol. 1998;29:944–952. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart A.F. Hypercalcemia associated with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:373–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]