Significance

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of pneumonia, a leading cause of death globally. Limitations in antibiotic efficacy and vaccines call attention to the need to develop our understanding of host–pathogen interactions to improve mitigation strategies. Here, we show that lung cells exposed to S. pneumoniae are subject to DNA damage caused by hydrogen peroxide, which is secreted by strains of S. pneumoniae that carry the spxB gene. The observation that S. pneumoniae secretes hydrogen peroxide at genotoxic and cytotoxic levels is consistent with a model wherein host DNA damage and repair modulate pneumococcal pathogenicity.

Keywords: DNA damage, Streptococcus pneumoniae, hydrogen peroxide, γH2AX, Ku80

Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a leading cause of pneumonia and one of the most common causes of death globally. The impact of S. pneumoniae on host molecular processes that lead to detrimental pulmonary consequences is not fully understood. Here, we show that S. pneumoniae induces toxic DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in human alveolar epithelial cells, as indicated by ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM)-dependent phosphorylation of histone H2AX and colocalization with p53-binding protein (53BP1). Furthermore, results show that DNA damage occurs in a bacterial contact-independent fashion and that Streptococcus pyruvate oxidase (SpxB), which enables synthesis of H2O2, plays a critical role in inducing DSBs. The extent of DNA damage correlates with the extent of apoptosis, and DNA damage precedes apoptosis, which is consistent with the time required for execution of apoptosis. Furthermore, addition of catalase, which neutralizes H2O2, greatly suppresses S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage and apoptosis. Importantly, S. pneumoniae induces DSBs in the lungs of animals with acute pneumonia, and H2O2 production by S. pneumoniae in vivo contributes to its genotoxicity and virulence. One of the major DSBs repair pathways is nonhomologous end joining for which Ku70/80 is essential for repair. We find that deficiency of Ku80 causes an increase in the levels of DSBs and apoptosis, underscoring the importance of DNA repair in preventing S. pneumoniae-induced genotoxicity. Taken together, this study shows that S. pneumoniae-induced damage to the host cell genome exacerbates its toxicity and pathogenesis, making DNA repair a potentially important susceptibility factor in people who suffer from pneumonia.

One of the most common causes of community-acquired pneumonia is Streptococcus pneumoniae, a commensal organism of upper respiratory tract (1). Pneumonia and other invasive pneumococcal diseases such as bacteremia, meningitis, and sepsis can be caused by S. pneumoniae, resulting in 1–2 million infant deaths every year (2). Secondary pulmonary infection by S. pneumoniae is commonly associated with higher mortality during major influenza pandemics (2). It is known that S. pneumoniae-induced cytotoxicity underlies pulmonary tissue injury during pneumonia and determines the outcome of infection (3). Furthermore, toxicity to alveolar epithelium disintegrates pulmonary architecture as well as weakens the alveolar-blood barrier, facilitating systemic bacterial dissemination. Although we have some understanding of bacterial virulence (4, 5), the underlying molecular processes in mammalian host cells that mediate tissue damage are not fully understood, which limits the development of mitigation strategies.

There are significant data supporting a role for inflammation as a cause for cytotoxicity during infection. S. pneumoniae is known to induce a robust inflammatory response at the site of infection that culminates with infiltration and accumulation of inflammatory cells including neutrophils and macrophages (6–8). To defend against infection, activated inflammatory cells produce high levels of genotoxic reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) including hydroxyl radical, superoxide, peroxide, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite. RONS-induced DNA lesions such as base damage, single-strand breaks, and double-strand breaks (DSBs) can be cytotoxic and thus damaging to host tissue function (9, 10). DSBs are one of the most toxic forms of DNA damage (11, 12). In response to DSBs, the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase pathway is activated, leading to Ser-139 phosphorylation of histone H2AX, forming γH2AX. The presence of γH2AX at DSBs recruits downstream DNA repair proteins, including 53BP1 and the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 (MRN) complex (13, 14). The major DSB repair pathway in nondividing cells is nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) (15). Early in NHEJ, Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer binds the damaged DNA ends. Ku80 plays a vital role in further recruitment and binding of the catalytic DNA-PKcs subunit (16). The DNA strands are then processed by nuclease activity of the MRN complex, and the DNA-PK holoenzyme recruits additional enzymes that complete the repair process (17). Despite the presence of efficient DSB repair, under conditions of excessive RONS, DNA damage can lead to cell death.

Although studies have been done to explore the damaging potential of RONS associated with the host response (18, 19), the possibility that S. pneumoniae might directly induce oxidative damage to DNA had not been explored. Studies focused on respiratory, as well as intestinal pathogens (20, 21), call attention to the importance of microbial-induced DNA damage as an important dimension of pathogenicity. For example, Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been shown to induce oxidative DNA damage in lung cells accompanied by significant tissue injury (22). These findings raise the possibility that S. pneumoniae may also induce DNA damage as a means for triggering host cell cytotoxicity. Although induction of cell death is key to pathogenicity, the underlying mechanisms by which S. pneumoniae induces apoptosis (23–25) and necrosis (26) in host cells is not yet well understood. Although it is known that certain pneumococcal proteins elicit a potentially cytotoxic inflammatory response (4, 27), here we asked whether S. pneumoniae or its secreted factors could directly generate DNA damage responses that could contribute to cell death. One such secreted factor could be hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), produced by action of pyruvate oxidase (encoded by spxB) in S. pneumoniae (28), H2O2 secreted by S. pneumoniae could potentially contribute to pneumococci-induced oxidative stress and elicit DNA damage response during infection. We used in vitro approaches to control H2O2 levels, and we also knocked out the spxB gene to reveal the impact of pneumococcal H2O2 in cells and animals. Specifically, we show that S. pneumoniae indeed has the potential to induce significant levels of DNA damage via secretion of H2O2 in vitro, that the levels of induced DNA damage contribute significantly to S. pneumoniae-induced toxicity, and that the spxB gene contributes to genotoxicity associated with disease severity in an animal model. Furthermore, we found that the key NHEJ repair protein Ku80 plays an important role in suppressing S. pneumoniae-induced genotoxicity and cytotoxicity. Together, the studies described here show that H2O2 secreted by S. pneumoniae is both genotoxic and cytotoxic and call attention to DNA damage and repair as previously unidentified factors in pneumococcal pathogenesis.

Results

S. pneumoniae Induces DNA Damage Responses in Alveolar Epithelial Cells.

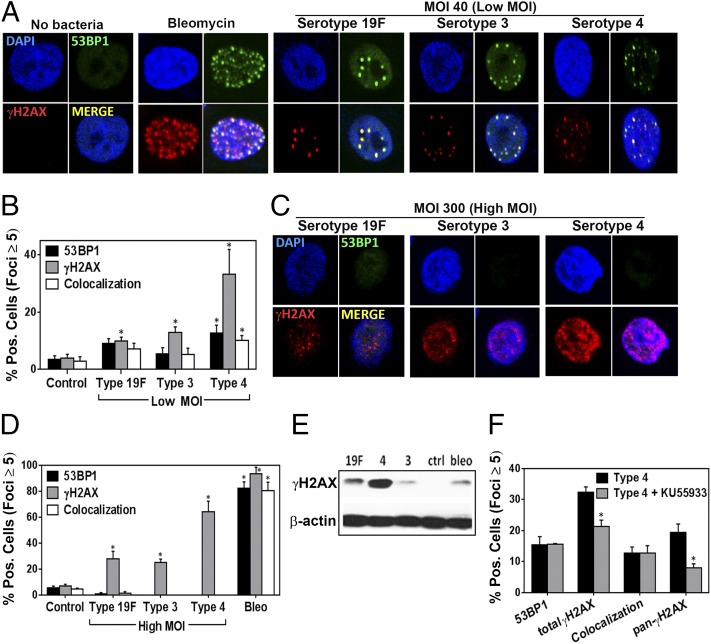

To learn whether S. pneumoniae has the ability to induce DNA damage in host cells, using immunohistochemistry, we measured the frequency of γH2AX foci, which form at sites of DSBs. We also quantified 53BP1 foci, which often colocalize with γH2AX at sites of DSBs. As expected, for untreated human lung epithelial cells, there were very few γH2AX or 53BP1 foci. In contrast, there were abundant foci in the nuclei of cells exposed to bleomycin, a known inducer of DSBs (Fig. 1A) (29). Furthermore, in addition to γH2AX appearing as punctate foci in bleomycin-exposed cells, we also observed nuclei with nearly uniform staining for γH2AX (Fig. S1C), which is consistent with studies showing that exposure to high levels of a DNA-damaging agent can result in nuclear-wide staining of γH2AX (pan-γH2AX) (30).

Fig. 1.

S. pneumoniae induces DNA damage in human alveolar (A549) cells in the form of DSBs. (A) Representative images of alveolar epithelial cells showing DSBs (indicated by γH2AX and 53BP1 foci) after exposure to S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 for 7 h at MOI 40 (Low MOI). Bleomycin (100 μM) serves as a positive control. (B) γH2AX- and 53BP1-positive cells (≥5 foci per nucleus) were quantified for each condition and expressed as percentage positive. (C–E) Alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 at MOI 200–400 (High MOI). (C) Representative images of alveolar epithelial cells after exposure to S. pneumoniae at MOI 300. (D) γH2AX- and 53BP1-positive cells were quantified for each condition. (E) The alveolar epithelial cells were also lysed and analyzed by Western for γH2AX. (F) Alveolar epithelial cells were pretreated with ATM inhibitor KU55933 (20 μM for 2 h) and then exposed to serotype 4 (type 4) at MOI 40 for 7 h. γH2AX-positive cells were quantified for each condition. For B and D, each data point represents mean ± SEM for four experiments. For F, each data point represents mean ± SEM for three experiments. For B, D, and F, *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

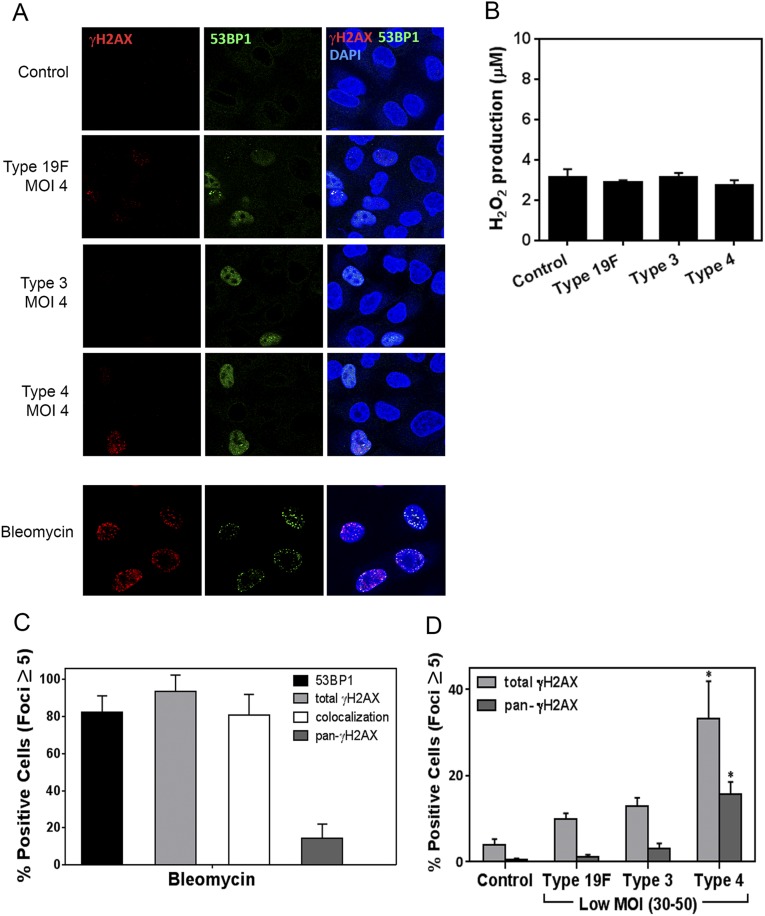

Fig. S1.

(A and B) S. pneumoniae does not induce DNA damage at MOI 3–5. (A) Representative images of alveolar epithelial cells analyzed for γH2AX and 53BP1 after in vitro infection with S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 for 7 h at MOI 4. Representative image of bleomycin (100 μM) treatment shown is taken on a different day using similar experimental protocol. Images are representative of three independent experiments. (B) H2O2 was also measured in the bacteria-free culture supernatant of these experiments. Results show mean ± SEM for three experiments. (C and D) Presence of pan-γH2AX during DNA damage. (C) Alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to bleomycin (100 μM) for 7 h and analyzed for γH2AX and 53BP1. After staining, γH2AX- and 53BP1-positive (for five or more foci per nucleus) cells were quantified. Results show mean ± SEM for three experiments. (D) Alveolar epithelial cells exposed for 7 h to 10-fold higher MOI for serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 (MOI 30–50) were analyzed for γH2AX. Percentage of positive cells (total γH2AX) from Fig. 1B is represented again here to contrast the subset of pan-γH2AX–stained cells. Serotype 4 shows significant DNA damage at MOI 30–50, whereas no significant damage induction was observed at MOI 3–5 (shown in A).

To determine if S. pneumoniae can induce DNA DSBs, alveolar epithelial cells were cocultured with three virulent serotypes of S. pneumoniae, namely, serotype 19F (clinical isolate), serotype 3 (Xen 10 strain), and serotype 4 (TIGR4). Strikingly, the presence of S. pneumoniae resulted in a significant increase in the frequency of DSBs, indicated by the presence of both γH2AX and 53BP1 foci, most of which colocalized (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, serotype 4 showed the strongest ability to induce DSBs. Quantification of the percentage of cells harboring a significant increase in DSBs [defined as having ≥5 foci of either γH2AX or 53BP1 (31)] revealed that for serotype 4, ∼30% and ∼15% of cells have increased γH2AX and 53BP1 foci, respectively (Fig. 1B). In addition to cells having punctate foci, there were also a significant number of cells pan-stained for γH2AX (∼45% of the total γH2AX-positive cells) (Fig. S1D), similar to what had been observed following exposure to bleomycin. Unlike cells showing clear repair foci, where γH2AX and 53BP1 mostly colocalize, 53BP1 did not stain in γH2AX pan-stained cells, which is consistent with previous observations (30, 32, 33). For serotypes 19F and 3, there was a greater frequency of γH2AX-positive cells compared with uninfected cells, although the ability of these serotypes to induce DSB foci was clearly reduced compared with serotype 4 (Fig. 1B). To determine if observations are specific to the A549 cell type, we performed studies of lung adenoma cells (LA-4). For LA-4 cells, we similarly observed that S. pneumoniae induces DSBs (Fig. S2). These data, as well as analogous results in vivo (see below), indicate that the results of these studies are not specific to one cell line. Finally, we found that induction of DNA damage depends on the multiplicity of infection (MOI). At lower MOI of 3–5, there was no significant increase in γH2AX or 53BP1 foci for any of the strains (Fig. S1A).

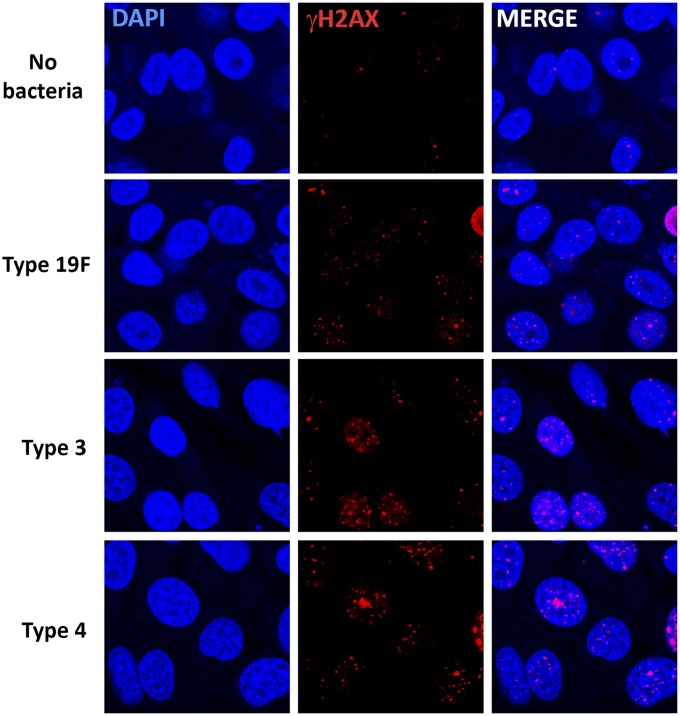

Fig. S2.

S. pneumoniae induces DNA damage in LA-4 mouse respiratory epithelial cells. Representative images of LA-4 cells analyzed for γH2AX after in vitro infection with S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 for 7 h at MOI 30–50. Images are representative from three independent experiments.

To further explore the potential for S. pneumoniae to induce DNA damage, alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to a higher concentration of S. pneumoniae. Given that up to ∼108 CFU/mL of S. pneumoniae have been reported to be present in infected human lungs (34), alveolar epithelial cells are likely to be exposed to high levels of S. pneumoniae during acute infections at focal lung regions. Therefore, we used MOI 200–400 for infection of all three serotypes. We found that all three serotypes induced DNA damage in more than 20% of cells, with serotype 4 inducing DNA damage in over 50% of the cells (Fig. 1D). In contrast to the experiments at MOI of 30–50, most cells that were positive for γH2AX were pan-stained (Fig. 1C), suggesting that, at higher MOI, elevated levels of DNA damage were induced (30). As an alternative approach, we also analyzed the levels of H2AX phosphorylation by Western. Consistent with immunofluorescence analysis, we observed significantly increased γH2AX protein levels in lysates of epithelial cells exposed to all three S. pneumoniae serotypes, with the highest levels being associated with serotype 4 (Fig. 1E). To further explore the possibility that H2AX phosphorylation was induced as a response to DSBs, we targeted the canonical DNA damage response pathway centrally regulated by ATM kinase (35). When cells were pretreated with specific ATM kinase inhibitor (KU55933) and then exposed to serotype 4, the frequency of cells with γH2AX staining (both punctate and pan) decreased significantly with respect to mock-treated cells (Fig. 1F), indicating activation of the ATM pathway in response to S. pneumoniae. Taken together, these results demonstrate that S. pneumoniae is able to induce DSBs in human alveolar epithelial cells, that DNA damage responses depend in part on ATM activity, and that the potency of S. pneumoniae-induced DSBs is serotype-dependent.

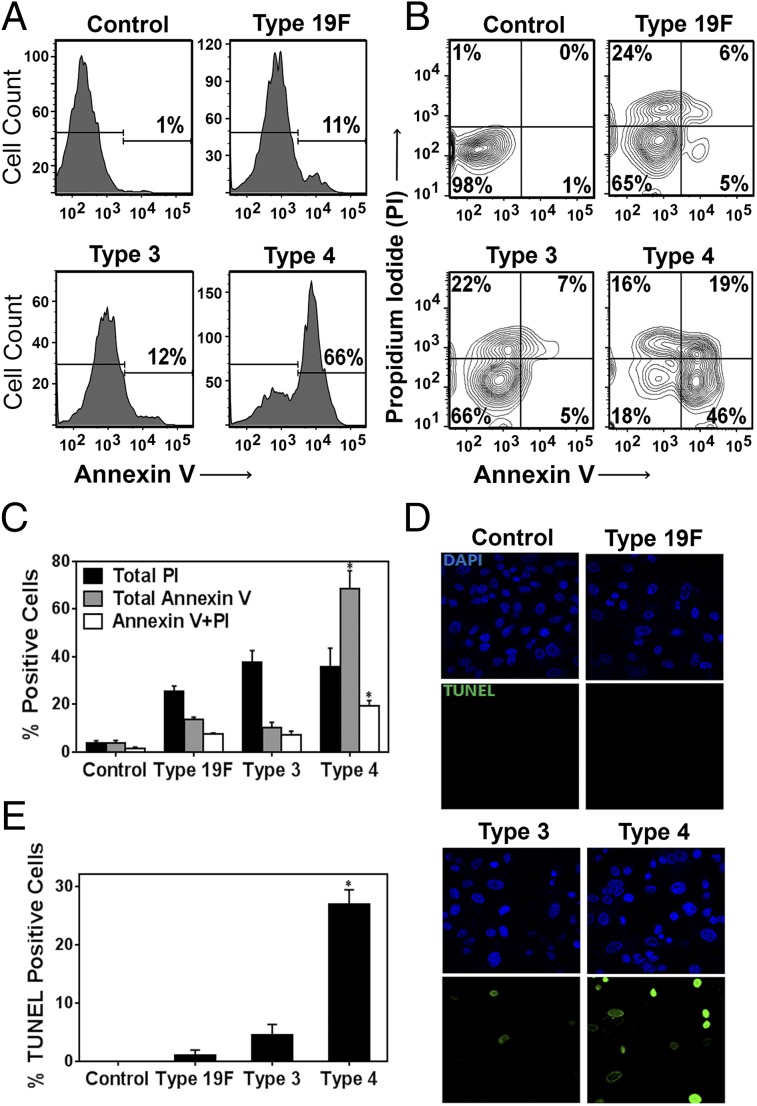

S. pneumoniae-Induced DNA Damage Levels Correlate with Levels of Apoptosis and Necrosis.

Host cell death is a key feature of S. pneumoniae pathogenicity (3, 23–26). To reveal the relative cytotoxicity of the three serotypes of S. pneumoniae, we exposed mammalian alveolar epithelial cells to S. pneumoniae. After the epithelial cells had been exposed to bacteria for 7 h in vitro, we analyzed cells for two key events of apoptosis, namely externalization of phospholipids (an early event detected by Annexin V) and late apoptotic fragmentation of DNA (detected by TUNEL). In addition, we analyzed cells for permeability to propidium iodide (PI), a measure of necrosis. All three serotypes induced apoptosis, as quantified using Annexin V (Fig. 2 A and C), with serotype 4 inducing the highest proportion of Annexin V-positive cells (∼65% apoptotic cells). All three serotypes also caused an increase in the proportion of PI-positive necrotic cells (25–35%) (Fig. 2 B and C). Additionally, serotype 4 had the highest proportion of Annexin V and PI dual-positive cells (late apoptotic or secondary necrotic, ∼20%) (Fig. 2C), as well as TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 2 D and E). The higher proportion of Annexin V-positive cells compared with TUNEL-positive cells is consistent with most cells still being in the early stages of apoptosis at 7 h postinfection (36). The robust ability of serotype 4 to induce apoptosis is also observed at lower MOI (30–50) (Fig. S3). Importantly, the levels of DNA damage correlate with the levels of apoptosis, which is consistent with S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage leading to apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

S. pneumoniae induces apoptosis in alveolar epithelial cells and the extent of apoptosis relates to the genotoxicity of each serotype. Alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to S. pneumoniae at high MOI (200–400) for 7 h and then analyzed by anti-Annexin V, PI, and TUNEL staining. (A) Representative histograms for cell count versus Annexin V staining. (B) Representative contour plots showing exposed cell populations analyzed by Annexin V and PI staining. (C) Annexin V, PI, and dual-positive cells were quantified. (D and E) Exposed cells were fixed and analyzed by the TUNEL assay. (D) Representative images of cells at late apoptotic stage (green TUNEL positive). (E) TUNEL-positive cells were quantified. For C and E, results show mean ± SEM for three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

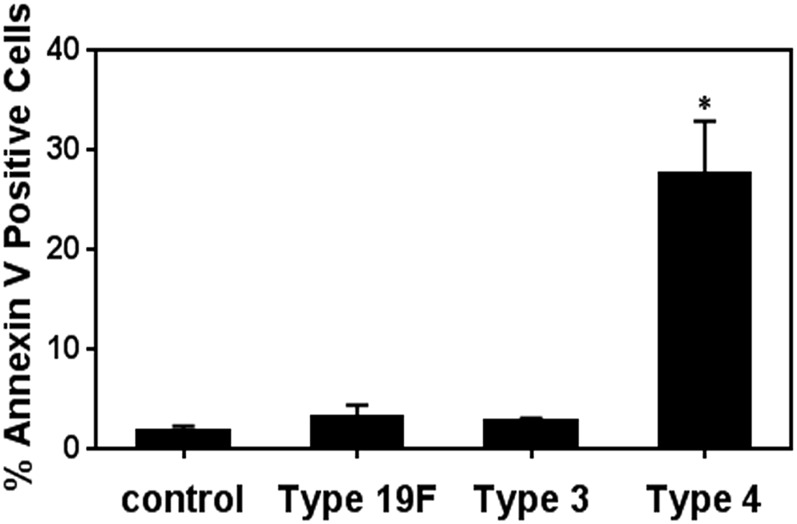

Fig. S3.

S. pneumoniae serotype 4 induces apoptosis at low MOI (30–50). Alveolar epithelial cells were infected with S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 at MOI 30–50. Early apoptosis was detected by staining for Annexin V and quantified by flow cytometry. Each data point represents mean ± SEM for three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

S. pneumoniae-Induced DNA Damage Precedes Apoptosis.

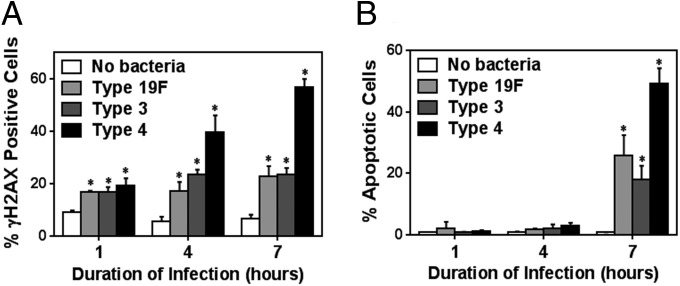

It is well established that DNA DSBs act as a signal to initiate apoptosis, which is then followed by execution of apoptosis, a process that can take many hours (11, 37). In the above experiments, DNA damage levels and apoptosis were evaluated at the same time (7 h after coincubation of alveolar epithelial cells and S. pneumoniae), making it unclear as to whether the observed DSBs could have signaled for apoptosis. To further explore the possibility that S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage induces apoptosis, we analyzed the levels of both DNA damage and apoptosis at 1, 4, and 7 h postinfection. Analysis shows that all three serotypes cause a significant increase in DNA damage as early as 1 h postinfection (Fig. 3A). The damage levels were then sustained or increased at 4 and 7 h postinfection depending on the serotype, with serotype 4 being the most damaging, as indicated by immunostaining and Western (Fig. 3A and Fig. S4). Importantly, we observed that apoptosis was significantly increased only at 7 h after infection (Fig. 3B), which is significantly later than the induction of DNA damage observed at 1 and 4 h postinfection. These results are consistent with delayed execution of apoptosis following induction of DSBs.

Fig. 3.

S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage response occurs before apoptosis. (A) Alveolar epithelial cells exposed to S. pneumoniae at high MOI (200–400) were analyzed and quantified for γH2AX at various times after exposure (1, 4, and 7 h). (B) Exposed cells were also analyzed for Annexin V and quantified by flow cytometry at 1, 4, and 7 h postinfection. For A and B, each data point represents mean ± SEM from three experiments. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

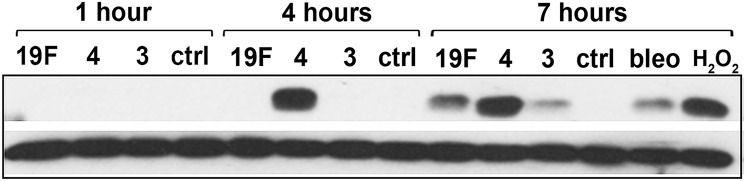

Fig. S4.

S. pneumoniae-induced γH2AX response analyzed by Western. Lysate of alveolar epithelial cells exposed to S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 at high MOI (200–400) were probed with anti-γH2AX antibodies (upper row) at 1, 4, and 7 h postinfection. Bleomycin (100 μM) and H2O2 (1 mM) serve as positive controls. Beta-actin is used as loading control (lower row). Representative blot showing γH2AX response from three independent experiments.

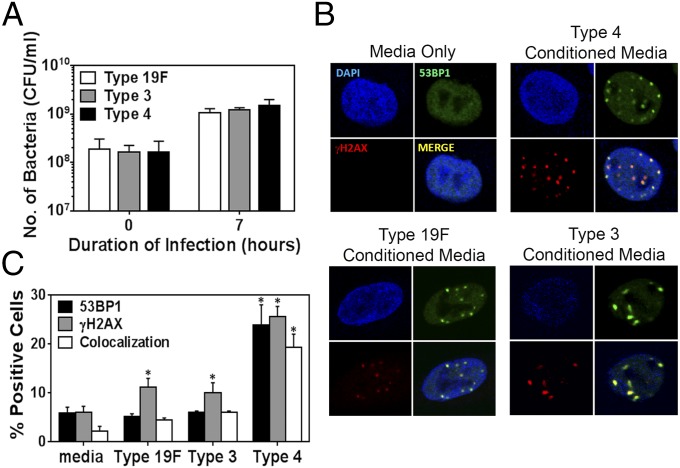

S. pneumoniae Can Induce DNA Damage in a Contact-Independent Fashion.

Recently, it was shown that the intestinal pathogen Helicobacter pylori requires direct contact with host cells to induce DSBs (20). In contrast, the related pathogenic species H. hepaticus is able to induce DNA damage in a contact-independent fashion by secreting a DNase-like factor that penetrates host cells (38). To understand the molecular basis for S. pneumoniae-induced DSBs, we explored the possibility that DNA damage is induced by any pneumococcal secreted factor. As a first step, we determined the efficacy of culturing S. pneumoniae in relevant media. All three serotypes grew well in F12-K media (used for alveolar epithelial cells), doubling approximately three times in 7 h (Fig. 4A). To study the DNA-damaging potential of secreted factors, supernatant was then isolated from log-phase S. pneumoniae cultured in F12-K media. Following filtration, the resultant conditioned media was incubated with alveolar epithelial cells for 7 h. For all three serotypes, we observed a significant induction of γH2AX and 53BP1 foci (Fig. 4 B and C). Interestingly, the damaging effects of conditioned media from serotype 4 are similar to the results for live serotype 4 (Fig. 1 B and D), pointing to secreted factor(s) as being the major cause of DNA damage.

Fig. 4.

S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage is independent from physical contact with host cells. (A) Analysis of culture density (cfu/mL) shows that all three strains of S. pneumoniae grow similarly well in F12-K culture media. (B and C) Alveolar cells were exposed to bacteria-free supernatant (Conditioned Media) from cultures of S. pneumoniae type 4, type 19F, and type 3 grown in F12-K media for 7 h. Exposed epithelial cells were analyzed for γH2AX and 53BP1. (B) Representative images of epithelial cells showing γH2AX and 53BP1 foci. (C) Quantification of γH2AX- and 53BP1-positive cells. Results show mean ± SEM from three experiments. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

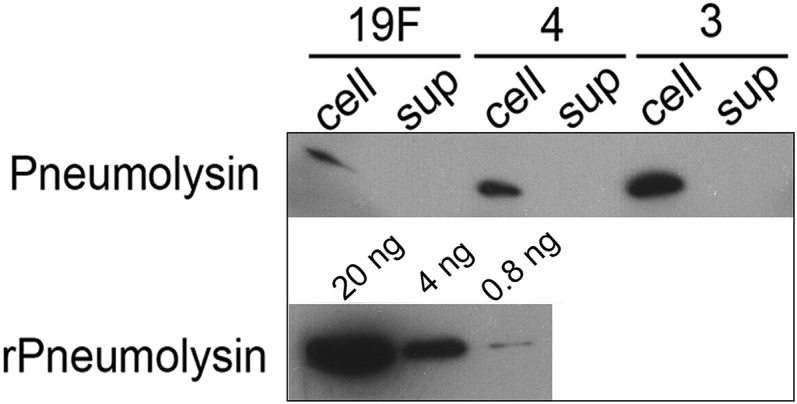

Another possible source of DNA damage is pneumolysin, a pneumococcal toxin that has been shown to cause apoptosis in alveolar cells when present at high concentrations in cell media in vitro (24). Although pneumolysin is cytoplasmic without any secretory signal (39), others have detected pneumolysin in bacterial supernatant (40, 41). To explore the possible importance of pneumolysin in inducing DNA damage and apoptosis, we assayed the cell culture supernatant for the presence of pneumolysin by Western (for all three strains). Consistent with its lack of a secretory signal, we did not detect pneumolysin in the F12-K media supernatant during infection of alveolar cells (Fig. S5). These results (together with results from studies of catalase; see below) indicate that secreted pneumolysin does not play a significant role in inducing DNA damage.

Fig. S5.

Pneumolysin is absent from S. pneumoniae supernatant. Alveolar epithelial cells were infected with S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 at high MOI (200–400) for 7 h. The culture medium was centrifuged and the bacterial pellets were analyzed by Western. Separately, after pelleting the bacteria, the supernatant was filtered through 0.2-μm filters and concentrated using Amicon ultra. Equal volumes (20 μL) of bacterial cell lysate and supernatant (with equal protein concentration) were then probed for pneumolysin by Western using anti-pneumolysin antibody. Recombinant pneumolysin (20 μL) in different concentrations served as a standard. A representative blot from three independent experiments is shown.

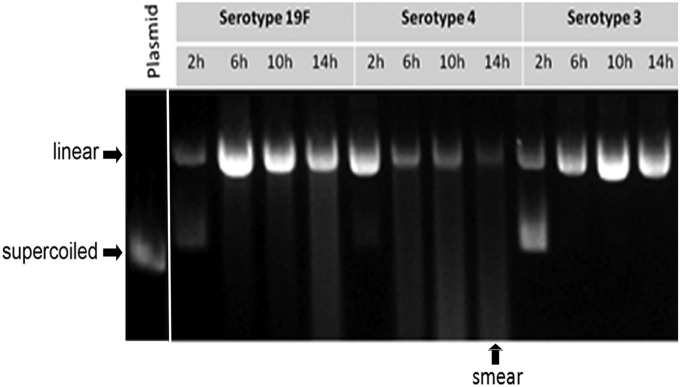

S. pneumoniae Secretes H2O2 at Genotoxic Levels.

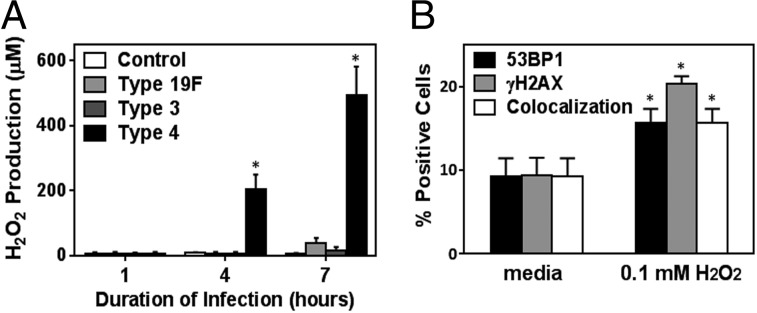

Previous studies show that some strains of S. pneumoniae produce H2O2 during aerobic metabolism. Given the known genotoxic potential of H2O2, we measured the levels of H2O2 in supernatant from all three serotypes of S. pneumoniae. During infection of human alveolar epithelial cells, we found that the ability of S. pneumoniae to produce H2O2 was variable among the three serotypes. For serotype 4, within 4 h postinfection of host cells in vitro, the concentration of H2O2 in the bacteria-free supernatant was more than 100 μM, and gradually the concentration increased up to 500 μM over the course of the following 3 h. In contrast, very little H2O2 was detected in the media of serotypes 19F and 3 (Fig. 5A). The difference in H2O2 production among serotypes was not a reflection of bacterial number (Fig. 4A). Moreover, ex situ, we observed that only the supernatant of serotype 4 was able to directly damage exogenous DNA (shown by assaying damage to supercoiled plasmid DNA) (Fig. S6). These results show that S. pneumoniae secretes H2O2 in a serotype-dependent manner and further demonstrate that H2O2 reaches DNA-damaging levels (upward of 500 μM) under coculture conditions.

Fig. 5.

S. pneumoniae produces genotoxic levels of H2O2. (A) H2O2 production was quantified in the bacteria-free culture supernatant at 1, 4, and 7 h postinfection with S. pneumoniae at high MOI (200–400). (B) Alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to pure 100 μM H2O2 and analyzed for γH2AX and 53BP1. Results show mean ± SEM for three experiments. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

Fig. S6.

Supernatant of S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 induces ex situ plasmid DNA damage. Bacterial supernatant was harvested from cultures of pneumococcal bacteria grown in BHI broth. After various amounts of time following inoculation, supernatant was filtered and incubated with a supercoiled pUC19 plasmid for 30 min. Left lane shows supercoiled plasmid (very little plasmid DNA is linear/nicked). After incubating DNA with filtered culture supernatant, the plasmids were then run in 0.8% agarose gel to test for plasmid damage as indicated by slow-migrating plasmid forms (nicked or linear).

To learn more about the biological significance of the observed levels of secreted H2O2, we analyzed the DNA-damaging potential of pure H2O2 at a concentration similar to what was observed under coculture conditions. When alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to 100 μM H2O2 in media, we observed that there is a significant induction of DNA damage in 15–20% of the exposed cells (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, H2O2 production for serotype 4 infection at 4 and 7 h parallels our previous observations of serotype 4-induced γH2AX [as observed both by immunostaining (Fig. 3A) and Western (Fig. S4)], consistent with H2O2 contributing to the induction of DNA damage. Interestingly, despite the relatively low level of H2O2 detected in the supernatants of serotypes 19F and 3 (Fig. 5A), these serotypes were nevertheless able to induce DNA damage (Figs. 3A and 4C) (discussed below). Taken together, these results show that H2O2 plays a significant role in pneumococci-induced DNA damage.

H2O2 Secreted by S. pneumoniae Causes DNA Damage and Cytotoxicity.

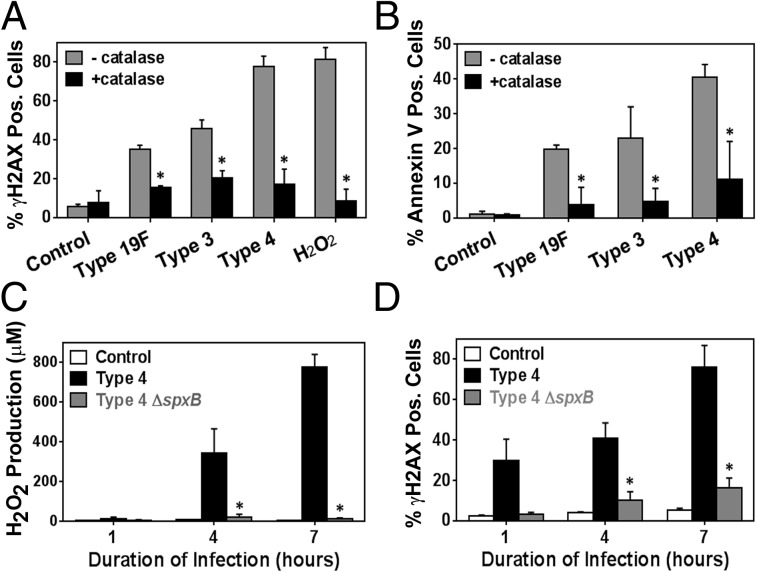

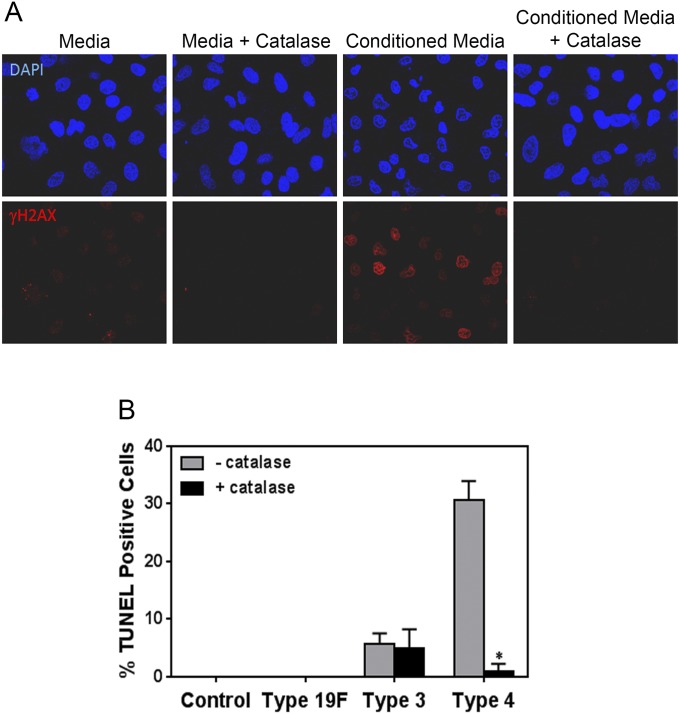

To further explore the biological significance of H2O2, we exploited catalase, an enzyme that neutralizes H2O2 to water. We observed that catalase reduces the frequency of DNA damage-positive cells by 50% or more in cultures of epithelial cells exposed to all three serotypes of S. pneumoniae (Fig. 6A). The impact of catalase on DNA damage was greatest for serotype 4 infection, which is consistent with its high level of H2O2 during infection. We then incubated the bacteria-free supernatant with epithelial cells in the presence or absence of catalase. Consistent with the coculture results, we found that catalase greatly suppresses the DNA-damaging potential of bacteria-free serotype 4 supernatant (Fig. S7A). Importantly, catalase treatment also suppressed the frequency of apoptotic cells as measured by Annexin V assay (Fig. 6B) and TUNEL for serotype 4 (Fig. S7B). Given the specificity of catalase, these results provide definitive evidence that H2O2 secreted by S. pneumoniae induces a significant level of DNA damage and apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

DNA damage induced by S. pneumoniae is mediated by its H2O2 production. (A) Analysis of γH2AX foci in alveolar epithelial cells exposed to S. pneumoniae serotype 4 at high MOI (200–400) with (+) or without (−) catalase (1 mg/mL). Cells are considered positive if there are five or more foci. (B) Using similar conditions, apoptotic cells were quantified via Annexin V staining. (C and D) Alveolar epithelial cells were exposed to serotype 4 wild-type (type 4) and H2O2-deficient ΔspxB mutant (type 4 ΔspxB) at MOI 300 for 7 h. (C) H2O2 in the bacteria-free culture supernatant was quantified at 1, 4, and 7 h postinfection. (D) Infected cells were analyzed for γH2AX foci. For A–D, control indicates absence of bacteria, and results show mean ± SEM for three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

Fig. S7.

Catalase suppresses serotype 4-induced DNA damage. (A) Catalase reduces DNA damage induced by supernatant from cultures of S. pneumoniae serotype 4. Representative images of alveolar epithelial cells analyzed for γH2AX after exposure to bacteria-free supernatant (Conditioned Media) from S. pneumoniae serotype 4, grown in F12-K media with or without catalase (1 mg/mL). Images are representative of three independent experiments. (B) TUNEL analysis of alveolar epithelial cells exposed to S. pneumoniae serotypes 19F, 3, and 4 at high MOI (200–400) with (+) or without (−) catalase. Results show mean ± SEM for three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

In S. pneumoniae, the pyruvate oxidase gene (spxB) produces H2O2 via pyruvate metabolism (28). We constructed an spxB mutant S. pneumoniae serotype 4 by introducing a kanamycin-resistance gene into the spxB gene of bacteria. As expected, H2O2 produced by spxB mutant bacteria was negligible (Fig. 6C). Further, we found that knocking out spxB eliminates the vast majority of the DNA-damaging potential of serotype 4 (Fig. 6D). These results show a direct correlation between S. pneumoniae’s genotoxicity and its ability to produce H2O2.

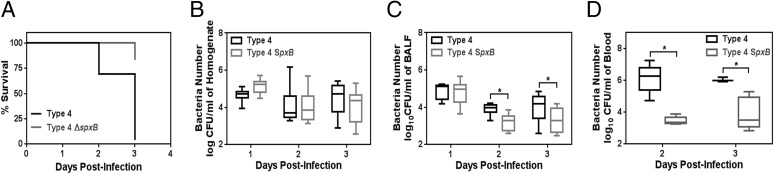

Ability of S. pneumoniae to Secrete H2O2 Is a Significant Virulence Factor.

To determine the relevance of pneumococcal H2O2 in disease progression in vivo, we used an acute pulmonary infection model of S. pneumoniae in mice, and we compared the virulence of S. pneumoniae serotype 4 with the H2O2-deficient spxB mutant strain. Both type 4 WT and type 4 ΔspxB were administered at similar cfu (2–3 × 107 cfu) via the intratracheal route, and the animals were monitored for up to 3 d. Type 4 WT infection induced severe symptoms, including lethargy, ruffled fur, and hunched back. Mice with the most severe symptoms either succumbed to disease or were humanely euthanized when reaching excess weight loss (≥20%). For type 4 WT, almost all of the animals had succumbed to disease after day 2 of infection. In contrast, type 4 ΔspxB was significantly less toxic and induced morbid symptoms in only a few animals by day 3 (3 of 24) (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Pneumococcal H2O2 promotes in vivo virulence and invasion. (A) Kaplan–Meier plot for animals infected with S. pneumoniae serotype 4 (type 4) and H2O2-deficient ΔspxB mutant (type 4 ΔspxB). BALB/c mice were infected with bacteria at ∼2 × 107 cfu per mouse via intratracheal inoculation (n = 23–24), and their mortality was monitored. Animals showing symptoms of severe illness (ruffled fur, hunch back, inactive) and ≥20% weight loss were humanely euthanized and considered as fatal cases. (B–D) In this model, pneumococcal cfu were determined in (B) lung homogenate after lavage (n = 9), (C) BALF (n = 9), and (D) blood of infected animals (n = 5). Data are shown in box and whisker plots with median (horizontal line), inner-quartile range (box), and maximum/minimum range (whisker). *P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney test.

To learn about the extent of infection, we determined the cfu of bacteria in lung homogenate, broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BALF), and blood. At days 2 and 3 postinfection, we found that, overall, spxB mutation did not significantly alter the bacterial cell number in lung homogenate (Fig. 7B). Importantly, however, when we measured cfu in the BALF of infected animals, we found that WT spxB conferred a virulence advantage by enabling invasion into the airways (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, we assessed cfu in the blood and found again that the presence of WT spxB confers an advantage for invasion into the blood circulation (Fig. 7D). Taken together, these in vivo studies show that the ability to secrete H2O2 renders bacteria more highly virulent.

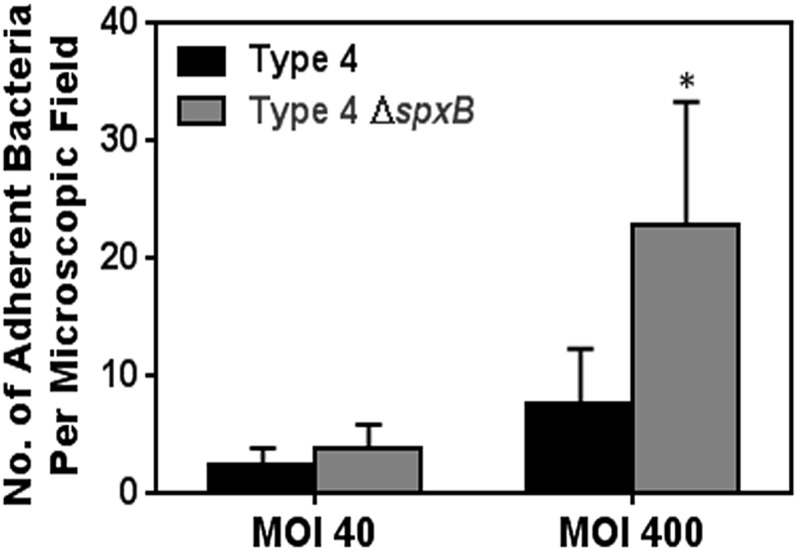

Although results point to the role of WT spxB in producing H2O2 as being critical to its genotoxicity and virulence, there remained the possibility that knockout of spxB impacted another virulence factor: adhesion. Previously, it was reported that spxB inactivation in an acapsular pneumococcal strain reduced bacterial adherence to alveolar cells, thereby reducing virulence (28). To determine whether spxB inactivation could reduce adhesive properties of the capsular type 4 strain used in this study, an adhesion assay was performed (28). It was found that inactivation of spxB did not reduce pneumococcal binding to alveolar cells (Fig. S8). These results show that the loss of virulence for ΔspxB is not due to loss of adhesion.

Fig. S8.

In vitro adhesion of S. pneumoniae serotype 4 is independent of spxB. Log-phase S. pneumoniae serotype 4 wild-type (type 4) and spxB mutant (type 4 ΔspxB) were labeled with FITC (1 mg/mL for 1 h) and incubated with alveolar cells for 1.5 h at 37 °C. The alveolar cells were then washed, and residual FITC-labeled bacteria were counted in a blinded fashion and expressed as the number of adherent bacteria per field. Results show mean ± SEM for five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test.

Pneumococcal H2O2 Mediates Pulmonary DNA Damage.

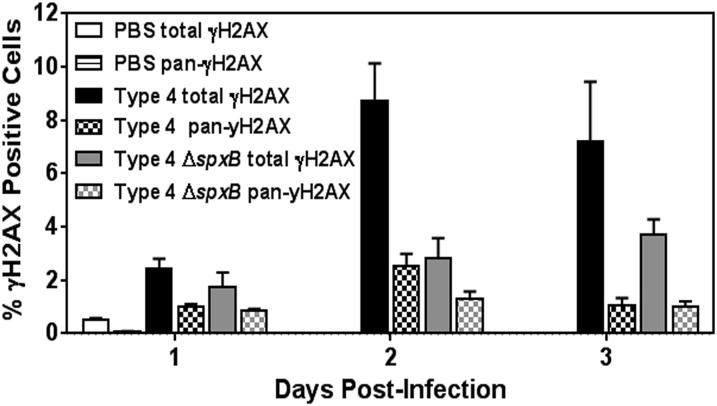

To learn about the impact of pneumococcal H2O2 on the genome of cells in vivo, we quantified the frequency of γH2AX-positive cells in lung sections. Consistent with our in vitro study, images show a higher frequency of γH2AX-positive cells in lungs of animals infected with serotype 4 WT (Fig. 8A). We found that only ∼2% of lung cells were positive for γH2AX on day 1 postinfection for both WT and ΔspxB S. pneumoniae. However, on day 2 postinfection, we observed a significant increase in γH2AX-positive cells (> 8%) in mice lung infected with type 4 WT, which was statistically significantly higher than that of type 4 ΔspxB (Fig. 8 A and B). At day 3 postinfection, results show a similar trend wherein there are more cells harboring DNA damage in mice infected with type 4 WT; however, this result is not statistically significant (Fig. 8 A and B).

Fig. 8.

Pneumococcal H2O2 is a major genotoxic factor during pathogenesis. (A and B) Lung sections of animals infected with type 4 WT and type 4 ΔspxB were analyzed for γH2AX at days 1, 2, and 3 postinfection (n = 9 per group, except for type 4 at day 3 where n = 5). (A) Representative images of lung section at days 1, 2, and 3 postinfection showing DAPI (blue), γH2AX (yellow), and costained nuclei (arrows). (Inset) Representative γH2AX-positive nucleus. (B) Frequency of γH2AX-positive cells (≥5 foci). (C and D) Inflammatory responses were evaluated at days 1, 2, and 3 postinfection. BALF from infected animals was analyzed by flow cytometry for (C) neutrophils and (D) macrophages (n = 9 per group, except for type 4 at day 3 where n = 5). (E) TNF-α concentration was determined in BALF using ELISA. Each data point represents data from one animal, and bars indicate the means. For B–D, results show mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

During pneumococcal pneumonia, there is persistent infiltration of inflammatory immune cells in the lungs that could themselves produce DNA-damaging RONS (6–8). Hence, inflammation-driven collateral damage to pulmonary cell DNA is plausible during S. pneumoniae infection. To determine whether there is a more robust inflammatory response for the mice infected with type 4 WT, the total number of macrophages and neutrophils were quantified. We observed that there was a statistically significantly lower number of neutrophils at days 2 and 3 and fewer macrophages at day 3 for animals infected with type 4 WT compared with type 4 ΔspxB (Fig. 8 C and D). If inflammation were to account for the observed DNA damage, one would expect to see reduced DNA damage for type 4 WT infected animals, whereas we observed the opposite. Therefore, the host inflammatory response does not account for the observed type 4 WT-induced DNA damage. Importantly, the level of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), a key proinflammatory cytokine, does not vary between type 4 WT and type 4 ΔspxB infection (Fig. 8E), suggesting similar overall levels of inflammation. Together with the results above, the reduced genotoxicity of S. pneumoniae type 4 ΔspxB is consistent with a deficiency of H2O2 synthesis, rather than differences in inflammation, thus supporting the significant role of pneumococcal H2O2 in pulmonary genotoxicity and disease severity.

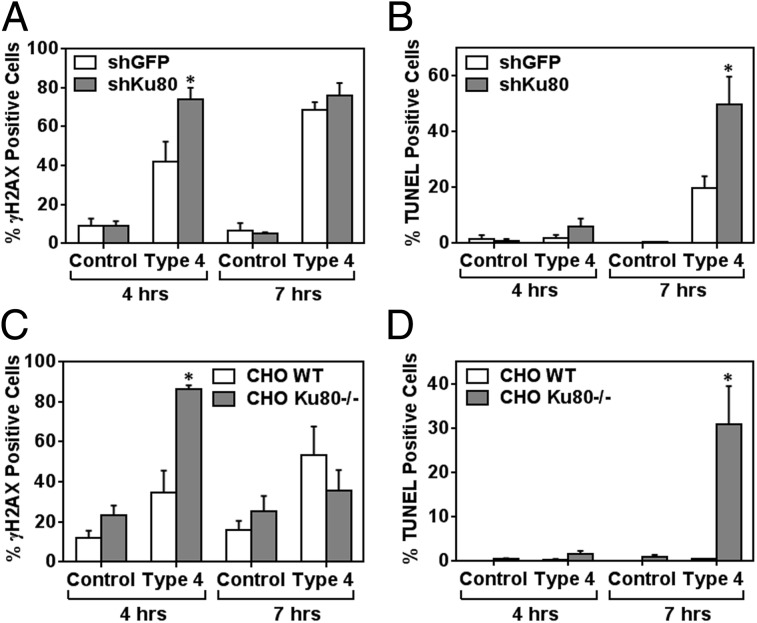

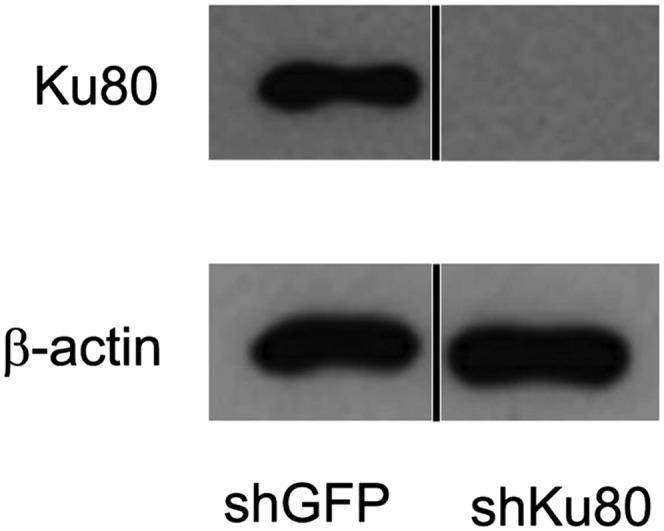

DNA Repair Deficiency in Host Cells Exacerbates S. pneumoniae Infection.

To learn about the potential importance of DNA repair during S. pneumoniae infection, we knocked down Ku80, which is indispensable for the NHEJ pathway [knockdown (KD) was performed using a lentiviral expression system for a short hairpin (shRNA) specific to Ku80 mRNA] (Fig. S9). The Ku80 knocked-down (Ku80 KD) cells were then infected with S. pneumoniae, and the proportion of DNA-damaged cells and apoptotic cells was quantified in vitro. At 4 h postinfection, there was a significantly higher frequency of γH2AX-positive Ku80 KD cells compared with negative control epithelial cells (with KD for GFP) (Fig. 9A). At the same time point (4 h postinfection), there were very few apoptotic cells (identified as being TUNEL-positive) (Fig. 9B). However, at 7 h, there was a significantly greater increase in the frequency of TUNEL-positive Ku80 KD cells compared with GFP KD cells, indicating that a deficiency in Ku80 leads to increases in the susceptibility of mammalian cells to S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage and subsequently to cell death by apoptosis. To further explore the potential role of Ku80 in response to S. pneumoniae, we exploited CHO cells that are null for Ku80. Similar to the results for knocked-down cells, we found that the Ku80-deficient CHO cells (CHO XRS6) were significantly more sensitive to S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage at 4 h (Fig. 9C) and to apoptosis at 7 h (Fig. 9D). These results definitively show that S. pneumoniae-induced cytotoxicity is due to DNA damage and call attention to the potential role for DNA repair in protecting mammalian cells against S. pneumoniae-induced genotoxicity.

Fig. S9.

Western analysis showing knockdown of Ku80 in alveolar cells. Alveolar epithelial cells knocked down for Ku80 (using shKu80) were lysed and probed using anti-Ku80 antibody. shGFP transfected cell lysate was used as a negative control and β-actin serves as a loading control. Black line separates lanes that were run on the same gel.

Fig. 9.

Deficiency in DNA repair exacerbates S. pneumoniae-induced cytotoxicity. (A) γH2AX was evaluated for alveolar epithelial cells with knocked-down Ku80 (shKu80) exposed to S. pneumoniae serotype 4 at MOI 100. (B) In parallel, apoptotic cells were quantified for TUNEL staining. Negative control samples show data for shRNA against GFP (shGFP). (C and D) CHO cells deficient in Ku80 were infected with S. pneumoniae serotype 4 at MOI 40 for 7 h. (C) Percentage of γH2AX-positive cells. (D) In parallel, apoptotic cells were quantified by TUNEL staining. For A–D, controls indicate absence of bacteria, and results show mean ± SEM for three to five independent experiments. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

Discussion

An understudied aspect of S. pneumoniae infection is its direct impact on host cells and in particular its potential to induce cytotoxic DNA damage. Here, we investigated DNA damage and repair in the context of human alveolar epithelial cells exposed to three major virulent serotypes of S. pneumoniae (clinical isolate serotype 19F, serotype 3 Xen 10, and serotype 4 TIGR4) that commonly infect young children (42). Among these serotypes, we found that serotype 4 is the most genotoxic and can induce pulmonary DNA damage during acute bacteremic pneumonia. Results show that S. pneumoniae elicits DNA damage responses in host cells and that serotype 4 is able to secrete high levels of H2O2, giving it the capacity to induce DNA damage and cell death. Moreover, pneumococcal H2O2 alone is able to induce discrete DSBs without bacterial contact. Consistent with a model wherein S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage triggers apoptosis, we observed that cells deficient in DSB repair have increased levels of apoptosis. Finally, results show that S. pneumoniae-secreted H2O2 plays a significant role in mediating pulmonary genotoxicity and systemic virulence in an animal model of acute pneumonia. This study underscores the genotoxic potential of pneumococcal H2O2 as well as the potential importance of DNA repair as a defense against S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage and apoptosis.

S. pneumoniae is the most common pathogen underlying community-acquired pneumonia. Pneumonia is the major cause of death in children less than 5 y old, accounting for around 19% of childhood deaths worldwide (WHO report), and it also poses a serious threat to the elderly population (43). Moreover, pneumonia from S. pneumoniae infection is frequently the cause of fatal secondary infections during influenza pandemics, such as the 1918 influenza pandemic and the recent 2009 pandemic (44, 45). Additionally, S. pneumoniae plays a major role in worsening morbidity associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (46). S. pneumoniae resistance to mainline therapeutics, such as penicillin and macrolides, has increased strikingly to more than 25% in recent years (47). Given the heavy disease burden and prevailing drug resistance associated with S. pneumoniae, alternative approaches are needed for streptococcal disease mitigation.

The plight of the host genome during infection-induced pathogenesis had been largely overlooked. Recently, however, certain pathogenic bacteria have been shown to cause damage to host DNA. For example, Chlamydia trachomatis (33) and H. pylori (20) have been proposed to elicit dysregulated cell proliferation and mutagenic DNA damage, which in turn are thought to promote bacterial-induced carcinogenesis (33). Interestingly, H. hepaticus and Camplyobacter jejuni have been shown to produce cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), a carcinogenic tripartite protein that shows DNase activity in host nuclei (48–50). Given these examples of pathogens that have evolved mechanisms to induce DNA damage in mammalian cells, it seemed plausible that the host genome might be an intended target of S. pneumoniae. Indeed, in the case of S. pneumoniae, although it was known that the spxB gene worsens infection (51, 52), our work points specifically to the ability of the spxB gene to induce DNA damage as the underlying driver of spxB-associated virulence. Furthermore, to date, the link between pathogen-induced DNA damage and disease has been focused primarily on cancer, whereas here we show an example of a pathogen-secreted DNA-damaging factor that has a direct association with pathogen-induced morbidity and mortality during infection.

Severe DNA damage can lead to apoptosis and necrosis (11, 53), which in turn lead to disintegration of lung architecture, promoting pulmonary failure. Here, we observed that S. pneumoniae could cause greater permeability of the cell membrane of host cells (observed as PI uptake), indicative of necrosis. H2O2 may contribute to necrosis, as well as exposure to the pneumococcal cell wall, which has previously been reported to be a necrosis-inducing factor (24, 26). With regard to apoptosis, we show that H2O2 secreted by S. pneumoniae leads to DNA damage in a contact-independent fashion and that the levels of H2O2 are sufficiently high to induce significant apoptosis (Annexin V and TUNEL-positive cells). These observations are consistent with previous in vitro studies showing that secreted H2O2 can contribute to S. pneumoniae-induced cytotoxicity (25).

H2O2-induced DNA damage and resultant cell death is anticipated to enable invasion of S. pneumoniae into the blood circulation. Indeed, consistent with a previous report (51), we observed reduced bacterial titers in blood following infection by type 4 spxB mutant bacteria compared with type 4 WT, underscoring the role of spxB and its H2O2 production in development of effective sepsis in our animal model. Previously, Regev-Yochay et al. demonstrated the competitive advantage of having spxB in a nasopharyngeal colonization model (52). It has been reported that spxB inactivation in acapsular pneumococcal serotype 2 strain reduces its adherence to alveolar epithelial cells (28). As this could play a role in virulence, we assayed bacterial adherence (28) and found that inactivation of spxB did not reduce the adherence of the capsular serotype 4 strain (Fig. S8), indicating that a reduction in adherence does not explain the observed reduction in virulence. It is likely that the reported role of spxB in adhesion is specific to acapsular strains (54, 55).

We also report an important and previously unidentified role of the DNA repair protein Ku80 in suppressing S. pneumoniae-induced genotoxicity. This observation is consistent with the known role of Ku80 in protecting alveolar epithelial cells (and other cell types) from gamma-irradiation–induced DSBs (56, 57). Overall, our data suggest a genotoxic model of pneumococcal pathogenesis whereby pneumococcal spxB-derived H2O2 induces host DNA damage that overwhelms the Ku80-dependent NHEJ repair pathway, leading to cell death. Ultimately, via increased DNA damage, the resultant cell death and tissue damage could enable pneumococci to become more virulent and invasive.

In previous studies of pathogen-induced DNA damage, DSBs have been visualized by immunofluorescence detection of γH2AX (20–22, 33, 58). In our analysis of γH2AX foci, we found that a relatively high MOI produces sufficient H2O2 in the media to reach genotoxic levels. At a significantly lower MOI of 3–5, S. pneumoniae was not able to secrete significant amounts of H2O2 (Fig. S1B) and hence did not induce any significant increase in DNA damage. However, during pulmonary infection in vivo, S. pneumoniae is known to cause focal pneumonia (59). Consequently, it is anticipated that there could be a significant DNA-damaging effect from S. pneumoniae in vivo at sites of locally high MOI.

Interestingly, during S. pneumoniae infection of alveolar epithelial cells, we observed two patterns of γH2AX staining depending on the MOI used. Low MOI (30–50) yielded foci of γH2AX with 53BP1 in almost half of the total γH2AX-positive population, whereas the other half portrayed pan-γH2AX phosphorylation without any 53BP1 staining. At higher MOI (200–400), only pan-γH2AX staining without 53BP1 was observed. During infection of animals, we observed that pan-γH2AX constituted about 30% of the total γH2AX analyzed in the lung sections (Fig. S10). The pan-γH2AX staining has been reported to occur in human fibroblast cells subjected to Adeno-associated virus (58, 60), Chlamydia (33), and UV and ionizing radiation (30, 61, 62). Recently, such nuclear-wide γH2AX has been shown to occur in highly DNA-damaged cells and is mediated by ATM kinase (30). Here, we found that most of the pan-γH2AX phosphorylation was dependent on ATM kinase and hence constituted part of the DNA damage response cascade induced by S. pneumoniae.

Fig. S10.

Analysis of total and pan-staining for γH2AX in lung sections from infected animals. Lung sections of mice infected with type 4 WT and type 4 ΔspxB were analyzed for γH2AX on days 1, 2, and 3 postinfection (n = 9 per group, except for type 4 at day 3 where n = 5). Percentage of positive cells (total γH2AX) from Fig. 8B is represented again here to contrast the subset of pan-γH2AX stained cells.

Although H2O2 clearly plays a significant role in the induction of DNA damage and downstream responses to S. pneumoniae, we also found evidence for H2O2-independent induction of DSBs. During bacterial incubation with alveolar epithelial cells, we observed ∼60% γH2AX-positive cells. Interestingly, only 30% of cells showed significant DNA damage when incubated with supernatant alone. It is possible that mammalian cell contact with S. pneumoniae causes DNA damage in host cells, independent of bacterial H2O2. One possibility is that direct contact of mammalian cells with S. pneumoniae could activate surface proteins in alveolar epithelial cells and produce signals that impact oxidative status and DNA damage response pathways. Indeed, S. pneumoniae is shown to activate the cJun-NH2-terminal kinase (25) pathway, which has the potential to phosphorylate H2AX (63). Direct contact-induced DNA damage is further supported by the observation that deletion of spxB (which is necessary for secretion of H2O2) in bacteria does not completely eliminate its ability to induce DNA damage. Thus, although it is clear that pneumococcal H2O2 plays an important role in inducing DNA damage, there remain alternative mechanisms by which S. pneumoniae can contribute to DNA damage.

To learn more about possible alternative mechanisms for S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage, we studied the common pneumococcal toxin, pneumolysin. At high levels (e.g., ∼20 μg/mL), pneumolysin has been shown to induce apoptosis in alveolar cells in vitro (24). Although pneumolysin is an intracellular protein without any signal peptide for secretion (39), it is known to be released during bacterial lysis (64), and there are reports of pneumolysin in culture supernatant of certain strains, even without bacterial lysis (40, 41). We therefore tested for the presence of extracellular pneumolysin in culture supernatants. We were unable to detect extracellular pneumolysin, which is consistent with its lack of a signal peptide for secretion. Thus, in the studies presented here, it is unlikely that alveolar cells experience pneumolysin at levels that are sufficient to induce DNA damage. Whether pneumolysin can induce DNA damage when the bacteria undergo lysis, either via autolysis or via action of bactericidal antibiotics, is an interesting question for future studies.

Given the low levels of H2O2 produced by serotypes 19F and 3, the observation that catalase could suppress the ability of these strains to induce DNA damage was unexpected. However, it is important to consider the approach that was used to estimate H2O2 secretion, namely to sample the media. For strains that have low-level production of H2O2, it may be that H2O2 is rapidly diluted in the media. However, if S. pneumoniae settle to form a layer above the human cells, the local concentration of H2O2 is anticipated to be far greater. Catalase would be anticipated to counteract genotoxicity of H2O2 under these conditions. Moreover, the fact that serotypes 19F and 3 are not as cytotoxic as serotype 4 is consistent with H2O2 being a dominant mechanism for the induction of DNA damage and apoptosis.

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria calls attention to the need for alternative strategies for mitigating disease. Furthermore, although the capsular polysaccharide-based vaccines have been able to reduce the prevalence of vaccine-targeted invasive serotypes in the past 2 decades (65), the serotypes not covered by these vaccines are still prevalent and invasive especially in patients with cardiopulmonary comorbidities or compromised immunity (66). Developing our understanding of the molecular processes that modulate the progression of pneumococcal disease is therefore an important step in advancing alternative treatment approaches for S. pneumoniae infection. Although immune-cell–induced RONS play a role in fighting infections, these inflammatory chemicals can also lead to collateral tissue damage. Furthermore, bacterially secreted H2O2 may exacerbate tissue damage caused by inflammation-induced RONS. Importantly, S. pneumoniae strains that secrete H2O2 clearly must have mechanisms to tolerate H2O2, and these mechanisms may render them resistant to H2O2 produced by immune cells. Thus, the use of H2O2-neutralizing antioxidants, in concert with antibiotic regime, may be appropriate during severe pneumococcal pneumonia. Indeed, antioxidants have been shown to confer positive outcome during pneumococcal meningitis in a rat model (67). Constant secretion of such oxidants by serotypes colonizing the upper respiratory tract (URT) can potentially damage the URT epithelia, destabilizing its normal barrier function [e.g., ciliary velocity and mucus production (68)] and facilitating carriage of S. pneumoniae to become more invasive. Given that certain strains of S. pneumoniae are resistant to H2O2 (69), and that H2O2 increases disease pathogenicity, our data suggest that determining the status of the spxB gene in pneumococcal isolates could prove helpful in guiding the use of antioxidants in disease treatment.

In this study, we have shown that S. pneumoniae creates high levels of H2O2 and that the levels of H2O2 are sufficiently high to induce DNA damage and apoptosis. We have shown that suppressing the levels of pneumococcal H2O2 either by treatment with catalase or by knocking out the gene necessary for H2O2 biosynthesis suppresses S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage and apoptosis. Furthermore, H2O2 secreted by S. pneumoniae plays a key role in pathogenesis, as shown by an acute pneumonia animal model. Importantly, human alveolar epithelial cells knocked down for an essential component of the dominant DSB repair pathway are more sensitive to S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage and apoptosis, highlighting DNA repair as a potentially important susceptibility factor. In conclusion, the results of this study point to a role for S. pneumoniae-induced DNA damage in disease pathology and open doors to new avenues for developing therapeutic strategies that either suppress DNA damage or enhance DNA repair during infection.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strains and Model.

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the National Advisory Committee for Laboratory Animal Research guidelines (Guidelines on the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes) in facilities licensed by the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore, the regulatory body of the Singapore Animals and Birds Act. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), National University of Singapore (permit nos. IACUC 117/10 and 54/11). Female BALB/c mice (7–8 wk) were purchased from InVivos Pte Ltd. and housed in an animal vivarium at the National University of Singapore. Mice were inoculated via intratracheal dosing of S. pneumoniae at 2–3 × 107 cfu in 50 μL sterile PBS. BALF was drawn from the right lung using 800 μL sterile PBS, and blood was collected via cardiac puncture before harvesting the lung tissues. BALF and blood was plated onto blood agar on the same day, with appropriate dilution. The left lung was fixed in paraformaldehyde and later embedded in paraffin. The right lung was frozen in liquid nitrogen and later homogenized in 2 mL PBS and plated for cfu count.

Cell Culture and Bacterial Strains.

S. pneumoniae serotypes and strains were serotype 3 (Xen 10 A66.1), serotype 4 (TIGR4), and serotype 19F (clinical isolate). Bacteria were cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Sigma #53286), supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated horse serum at 37 °C. The human lung alveolar carcinoma (type II pneumocyte) A549 cell line was maintained in F12-K medium (Gibco) with 15% (vol/vol) FBS at 37 °C with 5% CO2. For experiments, pneumococci were at midlog phase (OD600 of 0.3–0.35), and A549 cells were at 70–80% confluency. The spxB gene was cloned into pGEMT, and the kanR gene was introduced at the HindIII site of the spxB gene (70). To create type 4 ΔspxB, plasmid was transformed into bacteria in the presence of 200 ng CSP-1 peptide.

Construction of Ku80 KD A549.

Escherichia coli bacterial glycerol stock harboring Ku80 shRNA lentiviral constructs was purchased from Sigma (SHCLNG-NM_021141,TRCN 0000295856). Lentiviral constructs were packaged via cotransfection with pMD2.G and psPAX2 into 293T cells using X-tremeGENE9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche) to produce lentiviral particles. A549 cells were transduced with viral particles in the presence of 10 μg/mL Polybrene (Sigma) and were selected in 2 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma) 2 d after transduction. A549 cells were analyzed for Ku80 knockdown by Western analysis of cell lysates with an anti-Ku80 antibody (Santa Cruz).

Infection of Cells and Treatments.

Stocks of S. pneumoniae were thawed and grown in BHI medium supplemented with horse serum. Log-phase bacteria were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in F12-K medium before incubation with MOI 200–400 (high MOI), MOI 30–50 (low MOI), and MOI 3–5 for up to 7 h at 37 °C. Bacterial colonies were counted after plating onto soy blood agar and incubating at 37 °C for ∼24 h. Catalase (Sigma #C9322) treatment was done at 1 mg/mL in F12-K medium for 7 h.

Flow Cytometry.

For flow cytometry of BALF cells, neutrophils were gated at Gr-1+ CD11b+ population, whereas macrophages were gated at F4/80+ CD11b+ population. For apoptosis and necrosis assays, cultured cells were incubated with Annexin V- PeCy7 (eBioscience #88–8103-74) and then with PI (2 μg/mL). Formaldehyde-fixed cells were stored in PBS.

Immunofluorescence.

After incubation with bacteria, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, blocked with 3% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS for 40 min, and washed once with PBS. Primary antibodies against γH2AX (Ser-139) (Millipore #05–636) and 53BP1 (Santa Cruz #sc-22760) were used at 1:100 dilutions in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with coverslip. For TUNEL staining, the labeling enzyme (Roche #1 1684795 910) was incubated similarly for 1 h at 37 °C. Secondary antibody (Invitrogen) labeled with either Alexa 488 or 564 were used for γH2AX and 53BP1. SlowFade (Invitrogen) mounted slides were stored at −20 °C. For staining of 5-μm lung sections, antigen was retrieved using Dako retrieval buffer, the sections were blocked and incubated with anti-γH2AX antibody overnight and next day was stained with secondary antibody and mounted. All of the stained slides were examined under confocal microscope, and at least 9 images (at 3 × 3 sites) were taken of each well under 60× magnification for cell culture slides, and 20 random images of each lung section was taken under 40× magnification.

DNA Damage Quantification.

Olympus FV10 2.0 viewer was used for imaging and counting in the dark room. At least 200 cells were counted. Cells were categorized as those with (i) more than five distinct foci of γH2AX or 53BP1 per nucleus regardless of colocalization, (ii) nuclei with colocalized foci of γH2AX and 53BP1 counted as “overlap,” and (iii) pan-staining of γH2AX. Cells that showed colocalization of FITC and DAPI were counted as TUNEL-positive cells. For images from lung sections, DAPI was machine-counted using IMARIS software, and Zeiss Zen software was used to examine and count γH2AX-positive cells. All counting was done in a blinded fashion, and nuclei were selected by DAPI alone and subsequently analyzed for γH2AX.

Supernatant Assay.

To prepare bacterial supernatant, log-phase bacteria were grown in F12-K medium. After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered (0.2 μm) and immediately incubated with A549 cells.

H2O2 Assay.

To measure H2O2 levels, conditioned media was centrifuged, filtered (0.2 μm), and stored at −80 °C for analysis using a hydrogen peroxide assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biovision #K265-200).

Western Analysis.

Treated cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 10 min with 200 μL of 1× lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.8, 25 mM dithiothrietol, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol]. The lysate was centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was denatured at 100 °C for 10 min and stored at −20 °C. For culture supernatants, after filtration, supernatants were concentrated 10× using Amicon ultrafilter units (0.5 mL, 3 K) and denatured by heating. Protein concentration was quantified using the BioRad DC protein assay kit, and lysates were electrophoresed in 15% SDS/PAGE. Analysis was done using anti-γH2AX (Millipore #05–636) antibody or with anti-pneumolysin antibody and with secondary antibody conjugated with HRP (Dako) and later developed by adding Amersham ECL prime reagent (GE Life Science).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Andrew Camilli (Tufts University) for the gift of the TIGR4 strain and Dr. Yamada Yoshiyuki and Dr. Orsolya Kiraly for their valuable insights. This publication is made possible by the Singapore National Research Foundation and is administered by Singapore-Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Alliance for Research and Technology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. H.Y. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1424144112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(3):571–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Poll T, Opal SM. Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia. Lancet. 2009;374(9700):1543–1556. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazzaz JA, et al. Differential patterns of apoptosis in resolving and nonresolving bacterial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(6):2043–2050. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9806158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srivastava A, et al. The apoptotic response to pneumolysin is Toll-like receptor 4 dependent and protects against pneumococcal disease. Infect Immun. 2005;73(10):6479–6487. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6479-6487.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.del Mar García-Suárez M, et al. The role of pneumolysin in mediating lung damage in a lethal pneumococcal pneumonia murine model. Respir Res. 2007;8(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dallaire F, et al. Microbiological and inflammatory factors associated with the development of pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2001;184(3):292–300. doi: 10.1086/322021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu F, et al. Modulation of the inflammatory response to Streptococcus pneumoniae in a model of acute lung tissue infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39(5):522–529. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0328OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balamayooran G, Batra S, Fessler MB, Happel KI, Jeyaseelan S. Mechanisms of neutrophil accumulation in the lungs against bacteria. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43(1):5–16. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0047TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knaapen AM, Güngör N, Schins RPF, Borm PJA, Van Schooten FJ. Neutrophils and respiratory tract DNA damage and mutagenesis: A review. Mutagenesis. 2006;21(4):225–236. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. Oxidative DNA damage: Mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 2003;17(10):1195–1214. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0752rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaina B. DNA damage-triggered apoptosis: Critical role of DNA repair, double-strand breaks, cell proliferation and signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(8):1547–1554. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00510-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vamvakas S, Vock EH, Lutz WK. On the role of DNA double-strand breaks in toxicity and carcinogenesis. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1997;27(2):155–174. doi: 10.3109/10408449709021617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward IM, Minn K, Jorda KG, Chen J. Accumulation of checkpoint protein 53BP1 at DNA breaks involves its binding to phosphorylated histone H2AX. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(22):19579–19582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura AJ, Rao VA, Pommier Y, Bonner WM. The complexity of phosphorylated H2AX foci formation and DNA repair assembly at DNA double-strand breaks. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(2):389–397. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.2.10475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helleday T, Lo J, van Gent DC, Engelward BP. DNA double-strand break repair: From mechanistic understanding to cancer treatment. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6(7):923–935. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falck J, Coates J, Jackson SP. Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nature. 2005;434(7033):605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature03442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cromie GA, Connelly JC, Leach DRF. Recombination at double-strand breaks and DNA ends: Conserved mechanisms from phage to humans. Mol Cell. 2001;8(6):1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominis-Kramarić M, et al. Comparison of pulmonary inflammatory and antioxidant responses to intranasal live and heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae in mice. Inflammation. 2011;34(5):471–486. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Högen T, et al. Adjunctive N-acetyl-L-cysteine in treatment of murine pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(10):4825–4830. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00148-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toller IM, et al. Carcinogenic bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori triggers DNA double-strand breaks and a DNA damage response in its host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(36):14944–14949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun G, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection induces reactive oxygen species and DNA damage in A549 human lung carcinoma cells. Infect Immun. 2008;76(10):4405–4413. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00575-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu M, et al. Host DNA repair proteins in response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in lung epithelial cells and in mice. Infect Immun. 2011;79(1):75–87. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00815-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali F, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated human macrophage apoptosis after bacterial internalization via complement and Fcgamma receptors correlates with intracellular bacterial load. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(8):1119–1131. doi: 10.1086/378675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmeck B, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced caspase 6-dependent apoptosis in lung epithelium. Infect Immun. 2004;72(9):4940–4947. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.4940-4947.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.N’Guessan PD, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae R6x induced p38 MAPK and JNK-mediated caspase-dependent apoptosis in human endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94(2):295–303. doi: 10.1160/TH04-12-0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zysk G, Bejo L, Schneider-Wald BK, Nau R, Heinz H. Induction of necrosis and apoptosis of neutrophil granulocytes by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122(1):61–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colino J, Snapper CM. Two distinct mechanisms for induction of dendritic cell apoptosis in response to intact Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Immunol. 2003;171(5):2354–2365. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spellerberg B, et al. Pyruvate oxidase, as a determinant of virulence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19(4):803–813. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.425954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Ghorai MK, Kenney G, Stubbe J. Mechanistic studies on bleomycin-mediated DNA damage: Multiple binding modes can result in double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(11):3781–3790. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer B, et al. Clustered DNA damage induces pan-nuclear H2AX phosphorylation mediated by ATM and DNA-PK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(12):6109–6118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma GG, et al. MOF and histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16 are critical for DNA damage response and double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(14):3582–3595. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01476-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Feraudy S, Revet I, Bezrookove V, Feeney L, Cleaver JE. A minority of foci or pan-nuclear apoptotic staining of gammaH2AX in the S phase after UV damage contain DNA double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(15):6870–6875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002175107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chumduri C, Gurumurthy RK, Zadora PK, Mi Y, Meyer TF. Chlamydia infection promotes host DNA damage and proliferation but impairs the DNA damage response. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13(6):746–758. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piroth L, et al. Development of a new experimental model of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia and amoxicillin treatment by reproducing human pharmacokinetics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(10):2484–2492. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burma S, Chen BP, Murphy M, Kurimasa A, Chen DJ. ATM phosphorylates histone H2AX in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(45):42462–42467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan A, Reiter R, Wiese S, Fertig G, Gold R. Plasma membrane phospholipid asymmetry precedes DNA fragmentation in different apoptotic cell models. Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;110(6):553–558. doi: 10.1007/s004180050317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang XP, Liu F, Wang W. Two-phase dynamics of p53 in the DNA damage response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(22):8990–8995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100600108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liyanage NP, et al. Helicobacter hepaticus cytolethal distending toxin causes cell death in intestinal epithelial cells via mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Helicobacter. 2010;15(2):98–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker JA, Allen RL, Falmagne P, Johnson MK, Boulnois GJ. Molecular cloning, characterization, and complete nucleotide sequence of the gene for pneumolysin, the sulfhydryl-activated toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1987;55(5):1184–1189. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.5.1184-1189.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benton KA, Paton JC, Briles DE. Differences in virulence for mice among Streptococcus pneumoniae strains of capsular types 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are not attributable to differences in pneumolysin production. Infect Immun. 1997;65(4):1237–1244. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1237-1244.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balachandran P, Hollingshead SK, Paton JC, Briles DE. The autolytic enzyme LytA of Streptococcus pneumoniae is not responsible for releasing pneumolysin. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(10):3108–3116. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.10.3108-3116.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jefferies JM, Macdonald E, Faust SN, Clarke SC. 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(10):1012–1018. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.10.16794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weycker D, Strutton D, Edelsberg J, Sato R, Jackson LA. Clinical and economic burden of pneumococcal disease in older US adults. Vaccine. 2010;28(31):4955–4960. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fleming-Dutra KE, et al. Effect of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic on invasive pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(7):1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: Implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(7):962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Domenech A, et al. Serotypes and genotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing pneumonia and acute exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(3):487–493. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Appelbaum PC. Resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae: Implications for drug selection. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(12):1613–1620. doi: 10.1086/340400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fahrer J, et al. Cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) is a radiomimetic agent and induces persistent levels of DNA double-strand breaks in human fibroblasts. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014;18:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young VB, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of Helicobacter hepaticus cytolethal distending toxin mutants. Infect Immun. 2004;72(5):2521–2527. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2521-2527.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fox JG, et al. Gastroenteritis in NF-kappaB-deficient mice is produced with wild-type Camplyobacter jejuni but not with C. jejuni lacking cytolethal distending toxin despite persistent colonization with both strains. Infect Immun. 2004;72(2):1116–1125. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.1116-1125.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orihuela CJ, Gao G, Francis KP, Yu J, Tuomanen EI. Tissue-specific contributions of pneumococcal virulence factors to pathogenesis. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(9):1661–1669. doi: 10.1086/424596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Regev-Yochay G, Trzcinski K, Thompson CM, Lipsitch M, Malley R. SpxB is a suicide gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae and confers a selective advantage in an in vivo competitive colonization model. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(18):6532–6539. doi: 10.1128/JB.00813-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hegedus C, et al. Protein kinase C protects from DNA damage-induced necrotic cell death by inhibiting poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(12):1672–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Talbot UM, Paton AW, Paton JC. Uptake of Streptococcus pneumoniae by respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64(9):3772–3777. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3772-3777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanchez CJ, et al. Changes in capsular serotype alter the surface exposure of pneumococcal adhesins and impact virulence. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nussenzweig A, Sokol K, Burgman P, Li L, Li GC. Hypersensitivity of Ku80-deficient cell lines and mice to DNA damage: The effects of ionizing radiation on growth, survival, and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(25):13588–13593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang QS, et al. ShRNA-mediated Ku80 gene silencing inhibits cell proliferation and sensitizes to gamma-radiation and mitomycin C-induced apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma lines. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2008;49(4):399–407. doi: 10.1269/jrr.07096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwartz RA, Carson CT, Schuberth C, Weitzman MD. Adeno-associated virus replication induces a DNA damage response coordinated by DNA-dependent protein kinase. J Virol. 2009;83(12):6269–6278. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00318-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gray BM, Converse GM, III, Dillon HC., Jr Epidemiologic studies of Streptococcus pneumoniae in infants: Acquisition, carriage, and infection during the first 24 months of life. J Infect Dis. 1980;142(6):923–933. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fragkos M, Breuleux M, Clément N, Beard P. Recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors are deficient in provoking a DNA damage response. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7379–7387. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00358-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marti TM, Hefner E, Feeney L, Natale V, Cleaver JE. H2AX phosphorylation within the G1 phase after UV irradiation depends on nucleotide excision repair and not DNA double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(26):9891–9896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603779103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stiff T, et al. ATR-dependent phosphorylation and activation of ATM in response to UV treatment or replication fork stalling. EMBO J. 2006;25(24):5775–5782. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu C, et al. Cell apoptosis: Requirement of H2AX in DNA ladder formation, but not for the activation of caspase-3. Mol Cell. 2006;23(1):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paton JC, Andrew PW, Boulnois GJ, Mitchell TJ. Molecular analysis of the pathogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae: The role of pneumococcal proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:89–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richter SS, et al. Pneumococcal serotypes before and after introduction of conjugate vaccines, United States, 1999–2011(1.) Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(7):1074–1083. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.121830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luján M, et al. Effects of immunocompromise and comorbidities on pneumococcal serotypes causing invasive respiratory infection in adults: Implications for vaccine strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(12):1722–1730. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Auer M, Pfister LA, Leppert D, Täuber MG, Leib SL. Effects of clinically used antioxidants in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(1):347–350. doi: 10.1086/315658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wright DT, et al. Interactions of oxygen radicals with airway epithelium. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 10):85–90. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]