Abstract

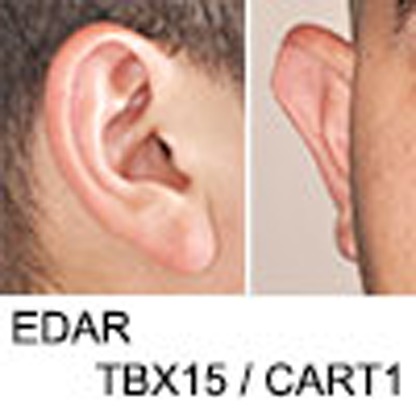

Here we report a genome-wide association study for non-pathological pinna morphology in over 5,000 Latin Americans. We find genome-wide significant association at seven genomic regions affecting: lobe size and attachment, folding of antihelix, helix rolling, ear protrusion and antitragus size (linear regression P values 2 × 10−8 to 3 × 10−14). Four traits are associated with a functional variant in the Ectodysplasin A receptor (EDAR) gene, a key regulator of embryonic skin appendage development. We confirm expression of Edar in the developing mouse ear and that Edar-deficient mice have an abnormally shaped pinna. Two traits are associated with SNPs in a region overlapping the T-Box Protein 15 (TBX15) gene, a major determinant of mouse skeletal development. Strongest association in this region is observed for SNP rs17023457 located in an evolutionarily conserved binding site for the transcription factor Cartilage paired-class homeoprotein 1 (CART1), and we confirm that rs17023457 alters in vitro binding of CART1.

The shape of the pinna varies widely in the general human population but the genetic basis of this variation is unknown. Here Adhikari et al. conduct a genome-wide association study in Latin Americans and discover seven gene regions influencing pinna morphology, including EDAR and TBX15.

The shape of the pinna varies widely in the general human population but the genetic basis of this variation is unknown. Here Adhikari et al. conduct a genome-wide association study in Latin Americans and discover seven gene regions influencing pinna morphology, including EDAR and TBX15.

The human pinna is made up of a piece of cartilage covered with skin and attached to the skull by ligaments, muscles and fibrous tissue. This cartilage does not extend into the ear lobe, which consists mostly of areolar and adipose tissue. A range of disorders affecting human pinna development have been described, occurring in isolation or as part of complex syndromes with multiple affected organs1,2. There is also great non-pathological variation between humans in pinna shape and size, and this variation has been reported to be influenced by age, sex and ethnicity3,4,5. The study of rare, familial microtia cases (a disorder characterized by a small, abnormally shaped pinna) has established that mutations in the HOXA2 gene can severely impact pinna development6. However, no genetic variants influencing normal pinna morphology have yet been reported. Here we aimed at identifying such variants by performing a genome-wide association study (GWAS) in a large sample of Latin American individuals with no pinna abnormalities. We identified seven loci with genome-wide significant association to variation in various pinna features, including several strong candidate genes with known developmental effects. We provide follow-up experimental evidence supporting the pinna morphology associations for two gene regions (which include the Ectodysplasin A receptor (EDAR) and the T-Box Protein 15 (TBX15) genes).

Results

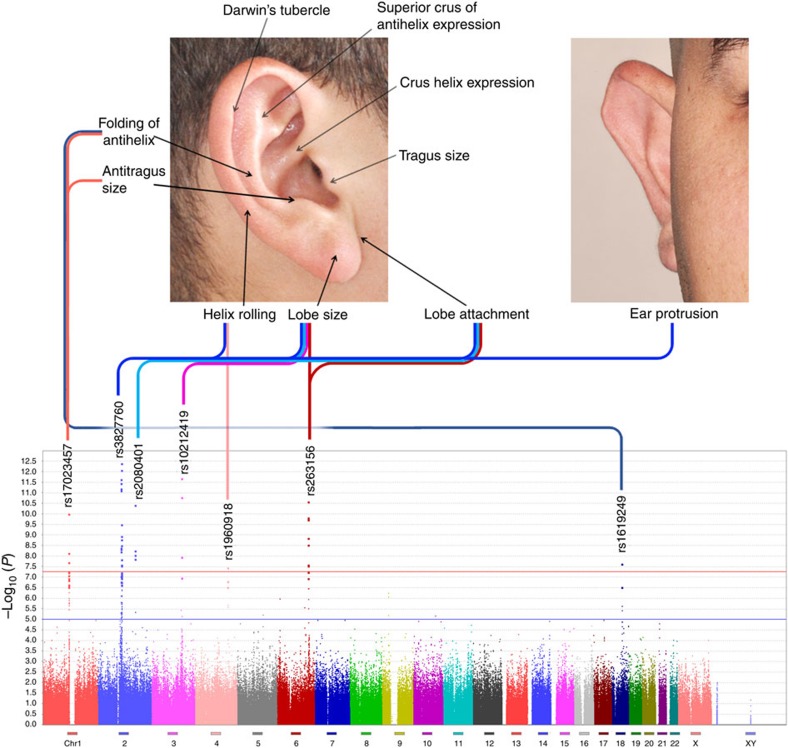

Our study sample is part of the CANDELA (Consortium for the Analysis of the Diversity and Evolution of Latin America; http://www.ucl.ac.uk/silva/candela) cohort collected in five Latin American countries (Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico and Peru) for the study of the genetics of physical appearance7. This sample consists of individuals of both sexes (median age 22 years), with a mixed African, European and Native American genetic background (Supplementary Table 1). Using facial photographs, we performed a qualitative assessment (on a three-point-ordered categorical scale; Fig. 1; Supplementary Figs 1 and 2) of 10 pinna traits in 5,062 individuals: ear protrusion, lobe size, lobe attachment, tragus size, antitragus size, helix rolling, folding of antihelix, crus helix expression, superior crus of antihelix expression and Darwin's tubercle.

Figure 1. Genome-wide associations of pinna traits.

Variation in 10 pinna traits was evaluated in 5,062 individuals. The photographs at the top indicate the location of the traits examined. At the bottom is shown a composite Manhattan plot for the seven traits showing genome-wide significant association with at least one genome region. The rs numbers for the most significantly associated (index) SNP in each region are provided (Table 1). Each of the seven regions on the Manhattan plot is connected with the associated trait on the photos via a line of different colour (composite panels in this and subsequent figures were made using Photoshop49).

Variation in the pinna traits examined

The trait scores show a weak-to-moderate correlation between them, and with age, sex, body mass index (BMI) and genetic ancestry (Supplementary Table 2). Most noticeably, lobe attachment shows a moderate and significant (permutation P value <0.001) negative correlation with lobe size (r=−0.49). Significant but weaker positive correlations were observed for folding of antihelix with helix rolling (r=0.25) and with superior crus of antihelix expression (r=0.23), as well as between ear protrusion and helix rolling (r=0.16).

Individuals were genotyped on Illumina's Omni Express BeadChip. After quality control, 671,038 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 4,919 individuals were retained for further analyses. Autosomal admixture proportions for the full sample were estimated as: 53% European, 43% Native American and 4% African (Supplementary Fig. 3). On the basis of a kinship matrix derived from the genome-wide SNP data8, we estimated narrow-sense heritability using GCTA9 and found moderate and significant values for all traits, with the highest heritability observed for ear protrusion (61%) and the lowest for tragus size (25%) (Supplementary Table 3). Similar heritabilities have been calculated for a range of facial traits using family data10,11.

Primary association analyses

For the primary genome-wide association tests, we applied multivariate linear regression, as implemented in PLINK12, using an additive genetic model adjusting for: age, sex, height, BMI and the first five principal components (PCs) calculated from SNP data. The resulting statistics showed no evidence of residual population stratification for any of the traits (Supplementary Fig. 4). To account for the possibility of cryptic relatedness between individuals, we also performed genome-wide association tests using random-effects mixed linear regression models (using FastLMM13) and obtained similar results as in the PLINK analyses (Supplementary Table 4). Six of the traits examined showed genome-wide significant association (linear regression P values <5 × 10−8) with SNPs in at least one of the seven genomic regions (Fig. 1; Table 1). A global false discovery rate test across all traits and SNPs identified the same significantly associated regions (Supplementary Table 5). Lobe size is associated with SNPs in four regions (2q12.3, 2q31.1, 3q23 and 6q24.2); three traits show association with two regions: lobe attachment (2q12.3 and 2q31.1), helix rolling (2q12.3 and 4q31.3) and antihelix folding (1p12 and 18q21.2). The remaining two traits show association with a single region: ear protrusion (2q12.3) and antitragus size (1p12). Since the traits examined show some correlation between them, the associations detected are likely not fully independent. Most noticeably, the moderate negative correlation observed between lobe attachment and size is consistent with SNPs at the same two loci (2q12.3 and 2q31.1) showing significant association with both traits. Suggestive association with lobe attachment is also observed for 6q24.2, which is significantly associated with lobe size (Table 1).

Table 1. Chromosomal location and −log10 (P) for index SNPs showing strongest genome-wide association to pinna traits.

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism. Trait acronyms (Fig. 1): AS, antitragus size; CHE, crus helix expression; DT, Darwin's tubercle; EP, ear protrusion; FoA, folding of antihelix; HR, helix rolling; LA, lobe attachment; LS, lobe size; SCoAE, superior crus of antihelix expression; TS, tragus size.

Genome-wide significant values (–log10 (P)>7.3) are highlighted in the darkest shade of red. Below this significance threshold, intensity of colour background is proportional to −log10 (P value). Effect sizes for associated alleles are shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 5. Intragenic SNPs are shown in bold. In 1p12, SNP rs17023457 is in an evolutionary conserved binding site for the CART1 transcription factor. GWAS P values were obtained using an additive multivariate regression model as described in Methods.

Secondary analyses

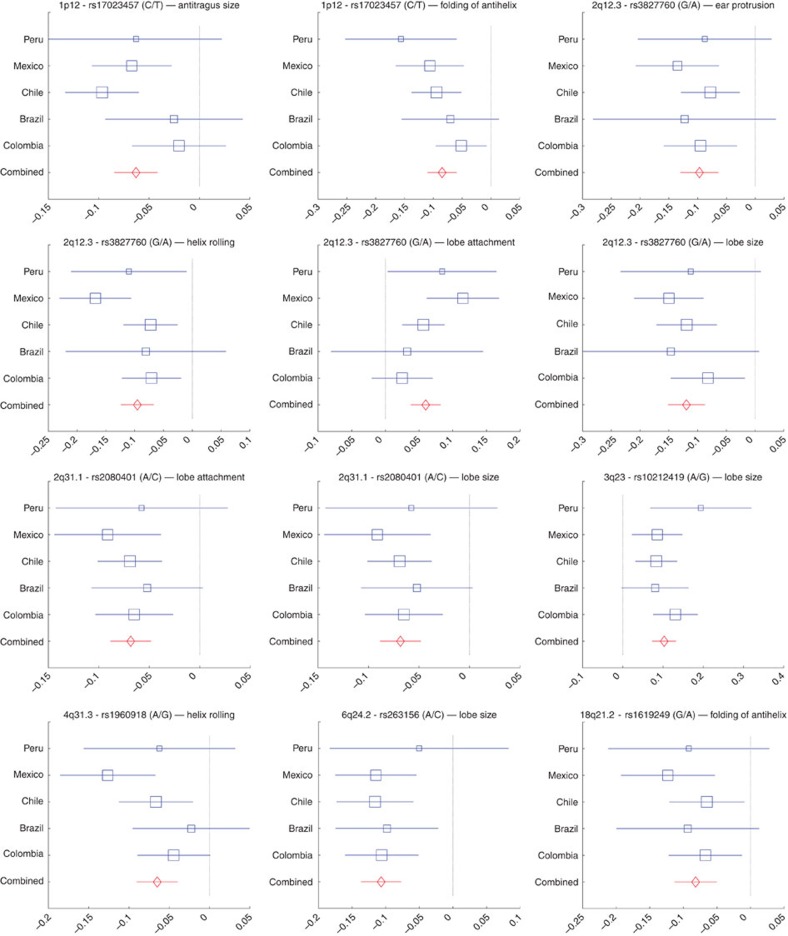

Since correlations between traits could have a shared underlying genetic basis, we performed a multivariate analysis combining all phenotypes in a single regression model (using MULTIPHEN14). This analysis identified the same set of regions as in the independent regression tests, but no additional associated regions (Supplementary Fig. 5). We also examined the association signals for all index SNPs (Table 1) in each country separately and combined results as a meta-analysis using METAL15. For each association, the effects were in the same direction in all countries, the variability of effect size across countries reflecting sample size (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 6; Supplementary Fig. 6a). There was no significant evidence of effect size heterogeneity across countries for any of the associations. A full genome-wide meta-analysis did not reveal additional regions showing significant association with pinna morphology (Supplementary Fig. 6b). The seven index SNPs of Table 1 provide modest phenotypic prediction accuracy (Supplementary Table 7). The fraction of the phenotypic variance explained by these SNPs is small relative to the heritability estimates (Supplementary Tables 3 and 7), suggesting a polygenic architecture for these traits beyond that captured by the genome-wide significance threshold used.

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of significant genome-wide associations.

Effect sizes (in each country sample and in a combined meta-analysis) for the index SNPs and their associated traits (Table 1). Regression coefficients (x axis) estimated in each country are shown as blue boxes (box size indicating sample size). Red diamonds indicate effect sizes estimated in the meta-analysis. Horizontal bars indicate s.e. Results for all the SNPs and traits shown in Table 1 are provided in Supplementary Fig. 6A. The two alleles at each SNP are shown in brackets with effect size referring to the allele in the numerator.

Features of associated regions

The genomic regions showing genome-wide significant association have features with independent evidence suggestive of an involvement in pinna development. This evidence is particularly strong for the regions in 2q12.3 and 1p12, and we followed-up these two regions with additional experiments.

2q12.3

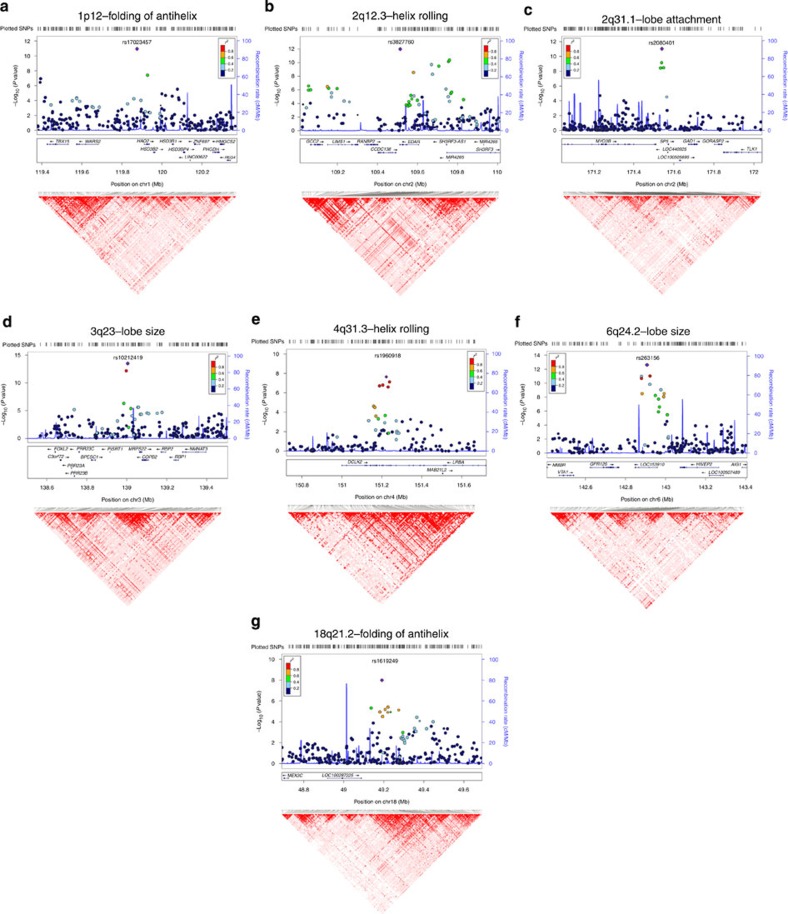

Includes SNPs associated with four traits (lobe size, lobe attachment, helix rolling and ear protrusion; Table 1). These SNPs extend over ∼500 kb and show substantial linkage disequilibrium (LD; Fig. 3b). Strongest association with all four traits was found for SNP rs3827760 (Table 1), and conditioning on this SNP abolishes the signal of association at other SNPs in the region (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Marker rs3827760 leads to a functional p.Val370Ala substitution in the intracellular death domain of EDAR. This residue affects the interaction with the EDAR-binding death domain adapter protein EDARADD16; the derived EDAR allele encodes a protein with higher activity than the ancestral one17,18. EDAR signalling acts during prenatal development to specify the location, size and shape of ectodermal appendages, such as hair follicles, teeth and glands19. The p.Val370Ala variant has been associated with characteristic tooth morphologies, hair type and sweat gland density in East Asians20,21,22,23,24,25, where this allele is present at high frequency while being nearly absent in European or African populations (Supplementary Table 8). Consistent with these effects in humans, mice expressing EDAR370A, or with increased EDAR function, show thickened and straightened hair fibres17,20,24,25.

Figure 3. LocusZoom and linkage disequilibrium plots of significantly associated genetic regions.

Plots of the seven genomic regions showing genome-wide significant association to pinna traits (Table 1). For regions showing association with several pinna traits, we present here only results for the trait with strongest association (plots for the other associated traits are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7). Association results from a multivariate linear regression model (on a −log10 P scale; left y axis) are shown for SNPs ∼500 kb on either side of the index SNP (that is, the SNP with the smallest P value, purple diamond; Table 1) with the marker (dot) colour indicating the strength of LD (r2) between the index SNP and that SNP in the 1000 Genomes AMR data set. Local recombination rate in the AMR data is shown as a continuous blue line (scale on the right y axis). Genes in each region, their intron–exon structure, direction of transcription and genomic coordinates (in Mb, using the NCBI human genome sequence, Build 37, as reference) are shown at the bottom. Plots were produced with LocusZoom56. Below each region we also show an LD heatmap (using D′, ranging from red indicating D′=1 to white indicating D′=0) produced using Haploview57. Note that the location of SNPs on the LD heatmap can be shifted relative to the regional display on top of it.

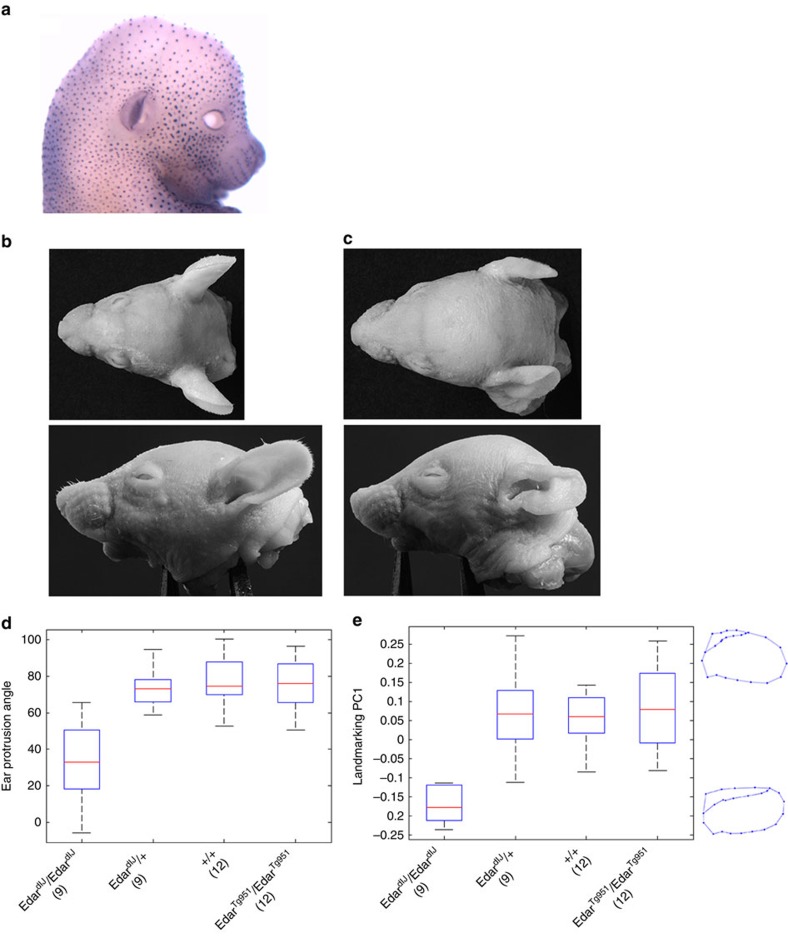

We examined Edar expression in the developing mouse embryo (Fig. 4a). The structure of the pinna is defined prenatally in both mouse and human, in mouse primarily between gestation days 13 and 16 (ref. 2). Using whole-mount in situ hybridization, we confirmed Edar expression along the distal margin of the developing pinna (Fig. 4a), in addition to the well-characterized expression in the developing hair follicles16. Edar expression at the distal margin of the embryonic pinna may aid in determining its growth and expansion, thus influencing the ultimate form adopted by the ear. To assess the functional significance of this Edar expression during pinna development, we examined postnatal pinna morphology in Edar mouse mutants. The EdardlJ (ref. 26) and EdarTg951 (ref. 16) mouse lines have a loss and a gain of Edar function, respectively (see Methods). At 2 weeks of age, the pinna of homozygous EdardlJ mice have a characteristic shape, including a marked dorsal/anterior folding (Fig. 4c). Quantitative assessment of mouse pinna protrusion (assessed by measuring protrusion angle) and shape (assessed by PC analysis of two-dimensional landmark coordinates) revealed significant differences (linear regression P value <0.0007; Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Figs 9 and 10) between the homozygous EdardlJ/dlJ mutant and heterozygous EdardlJ/+ littermates, wild-type mice and EdarTg951 mice. Landmark coordinate PC1, capturing 69% of the variation in shape, reflects mainly a change in the extent of helix rolling of the mouse pinna (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Fig. 10d), consistent with one of the effects we observed of EDAR variants on human pinna shape. The Edar high copy-number transgenic (EdarTg951) does not display a detectable change in helix rolling likely due to the fact that the wild-type mouse pinna does not have a prominent helix roll, thus hampering the detection of any further pinna flattening that might be caused by increased Edar function.

Figure 4. Effect of Edar genetic variation on mouse pinna shape.

(a) Whole-mount in situ hybridization detecting Edar expression in the developing mouse embryo at 15 days' gestation. (b–e) Impact of Edar genotype on mutant mouse ear shape. (b,c) Photographs of wild-type (b) and homozygous EdardlJ (c) mutant mice from top and side views (respectively, on the upper and lower panels). (d,e) Boxplots, respectively, of ear protrusion angle and of landmark coordinate PC1 (y axis) for different mouse genotypes (x axis) (Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Fig. 10 shows additional analyses for ear protrusion). Boxplot whiskers extend to data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range on both sides. In d,e numbers in parenthesis below genotypic categories refer to the number of mice examined for each. On the right of e are shown average PC1 wireframes for EdardlJ homozygous mice (bottom) or for mice with other genotypes (top).

1p12

SNPs in this region show genome-wide association with antihelix folding and antitragus size. This region extends over ∼800 kb and overlaps the gene encoding transcription factor TBX15 (Fig. 3a), a key regulator of cartilaginous and skeletal development in the mouse27. A spontaneous Tbx15 mouse mutant (called ‘droopy ears'), is characterized by altered positioning, projection and shape of the pinnae28,29. In humans, mutations of TBX15 result in Cousin syndrome, a disorder characterized by craniofacial dysmorphism, including a dysplastic pinna30. Strongest association in this region was observed for intergenic SNP rs17023457 (P value 2 × 10−8 for antitragus size and 1 × 10−11 for antihelix folding Table 1) and conditioning on this SNP abolishes the signal of association at other markers (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Interestingly, rs17023457 is located in a highly conserved binding site for transcription factor CART1 (cartilage paired-class homeoprotein 1) (Supplementary Fig. 11a), mutations of which have been shown to result in a range of craniofacial and cartilage abnormalities in the mouse31. The location of rs17023457 in a CART1-binding site strongly suggests that this SNP could directly influence the expression of neighbouring genes involved in cartilaginous development, such as TBX15.

To assess the potential for rs17023457 to alter DNA–protein interactions involving the CART1-binding site, electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed using nuclear extracts from a CART1-expressing cell line (Huh7). Double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the rs17023457 T allele demonstrated binding of a nuclear protein, this binding being undetectable for oligonucleotides carrying the derived C allele (Supplementary Fig. 11b). Binding was eliminated upon prior incubation with excess unlabelled CART1 consensus sequence DNA, confirming the specificity of the assay and supporting the ability of the sequence containing the T allele to bind CART1 in vitro. Reporter constructs containing either the rs17023457 T or C alleles driving the expression of the luciferase gene, showed a decreased expression of 36 and 22% in constructs with the C allele when the genomic sequence was positioned in the forward and reverse orientation, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 11b). These data indicate that CART1, or other nuclear DNA-binding proteins with the same sequence specificity, is able to bind to an enhancer that includes rs17023457, with variation at this SNP determining whether binding and full transactivation occurs or not. The implications of these observations for the in vivo regulation of TBX15 expression remain to be established.

Other regions

For the other regions showing genome-wide association, there is currently less compelling information suggestive of a mechanism explaining their effect on pinna morphology, and we did not attempt their experimental follow-up. SNPs in 3q23 are associated with lobe size, with strongest association being seen for intergenic SNP rs10212419 (P value 3 × 10−14), in a region with substantial LD over ∼500 kb (Fig. 3d). Intriguingly, considering that the ear lobe is made up mainly of loose connective tissue, intergenic SNPs in this region have been strongly associated with keloid formation32, an exaggerated skin wound-healing reaction characterized by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix and collagen fibres. Some highly penetrant mutations across this genomic region have also been found to result in alterations of craniofacial development involving pinna morphology. The gene nearest to SNP rs10212419 (∼59 kb away) encodes mitochondrial ribosomal protein S22 (MRPS22), mutations of which can lead to combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 5 (COXPD5), a disorder whose phenotype can include low-set, posteriorly rotated ears (OMIM #611719). A report of a patient with a similar ear phenotype found a non-synonymous substitution at an evolutionary conserved site within MRPS22 (ref. 33). Another interesting candidate gene in the vicinity is that encoding the forkhead box L2 transcription factor (FOXL2). Coding and regulatory mutations of this gene cause BPES (blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus syndrome)34,35, a disorder characterized by a range of craniofacial abnormalities, including alterations in ear lobe morphology36.

The 2q31.1 region shows considerable LD over ∼100 kb and is associated with lobe attachment and size, with strongest association seen for intergenic SNP rs2080401 (P values of 9 × 10−12 and 1 × 10−10 for these two phenotypes, respectively; Fig. 3c). This SNP is located ∼31 kb upstream of the gene encoding Specificity Protein 5 (SP5), a Sp1-related transcription factor that mediates responses to Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Of potential interest, there is evidence of an involvement of this pathway in musculo-skeletal development37,38. The region in 6q24.2, associated with lobe size, shows substantial LD over ∼500 kb overlapping the hypothetical protein-coding gene LOC153910. Strongest association was seen for intronic rs263156 (P value 2 × 10−13; Fig. 3f). Potentially of relevance to ear development, about 100 kb from rs263156 is GPR126 (G protein-coupled receptor 126), a gene strongly associated with human height39,40,41. Borderline genome-wide significance was found for rs1960918 in 4q31.3 (P value 2 × 10−8 for helix rolling; Fig. 3e) and rs1619249 in 18q21.2 (P value 1 × 10−8 for antihelix folding; Fig. 3g). Intronic marker rs1960918 is in an LD region of ∼400 kb overlapping the LRBA gene, whose product (LPS-responsive vesicle trafficking, beach and anchor containing) is known to be involved in coupling signal transduction, vesicle trafficking and immunodeficiency, with no obvious functional connection to pinna development. Intergenic SNP rs1619249 is in an LD region of about 300 kb, the closest candidate being LOC100287225 (about 100 kb from rs1619249), a hypothetical gene of unknown function.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have identified the first genetic variants influencing normal variation in human pinna morphology. It will be important to evaluate further the role of these regions in ear development and its disorders. Since pinna morphology in mammals shows extensive evidence of evolutionary adaptation, particularly in relation to thermoregulation, acoustic perception and sound localization42,43,44,45, it will be interesting to examine whether variation in these genomic regions relates to adaptive changes in the pinna across species. Finally, there is increasing interest in the use of pinna variation in forensics45,46, and development of such applications may benefit from a refined knowledge of the genetic determinants of pinna morphology.

Methods

Study subjects

In total, 5,062 volunteers from 5 Latin American countries (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru), part of the CANDELA consortium sample (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/silva/candela)7, were included in this study. Ethics approval was obtained from: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (Mexico), Universidad de Antioquia (Colombia), Universidad Perúana Cayetano Heredia (Peru), Universidad de Tarapacá (Chile), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) and University College London (UK). All participants provided written informed consent. Blood samples were collected by a certified phlebotomist and DNA extracted following standard laboratory procedures. Five digital photographs of the face: left side (−90°), left angle (−45°), frontal (0°), right angle (45°) and right side (90°) were taken from ∼1.5 m at eye level using a Nikon D90 camera fitted with a Nikkor 50 mm fixed focal length lens. Other phenotypes including height, weight, BMI, age and sex were also recorded for each participant7.

Pinna phenotyping

Right side, right angle and frontal photographs were used to score 10 pinna traits. These were (Fig. 1): ear protrusion, lobe size, lobe attachment, tragus size, antitragus size, helix rolling, folding of antihelix, crus helix expression, superior crus of antihelix expression and Darwin's tubercle. Each trait was scored as an ordered categorical variable, with 0 being the lowest level of expression of the trait and 2 the highest (Supplementary Fig. 1). Software to assist scoring of photographs was developed in MATLAB47. Intraclass correlation coefficients48 calculated by double-scoring photographs of 100 subjects indicate a moderate-to-high intra- and inter-rater reliability of the trait scores (Supplementary Table 9). Photographs for all the volunteers were scored by the same rater (G.R.).

DNA genotyping and quality control

DNA samples from participants were genotyped on the Illumina HumanOmniExpress chip including 730,525 SNPs. PLINK12 was used to exclude SNPs and individuals with >5% missing data, markers with minor allele frequency <1% and related individuals. After applying these filters, 680,634 SNPs were retained for further analysis. Owing to the admixed nature of the study sample (Supplementary Fig. 3), there is an inflation in Hardy–Weinberg P values. We therefore did not exclude markers based on the Hardy–Weinberg deviation.

Statistical analyses

P values for Pearson correlation coefficients were obtained by permutation. All regressions were performed using an additive multivariate linear or logistic model, providing P values that are obtained from the standard t-statistic derived from their regression coefficients. Narrow-sense heritability (defined as the phenotypic variance explained by a genetic relatedness matrix, GRM, computed from the SNP data) for the pinna traits examined was estimated using GCTA9 by fitting an additive linear model with a random-effect term whose variance is given by the GRM, with age, sex, height and BMI as covariates. The GRM was obtained using the LDAK approach8, which accounts for LD between SNPs. An LD-pruned set of 93,328 autosomal SNPs was used to estimate continental ancestry using ADMIXTURE49 (Supplementary Fig. 3). PLINK12 was used to perform the primary genome-wide association tests for each phenotype using multiple linear regression with an additive genetic model incorporating age, sex, height, BMI and 5 (or 10) genetic PCs as covariates. These genetic PCs were obtained (using MATLAB47) from an LD-pruned set of 93,328 SNPs. Inspection of the scree plot (Supplementary Fig. 4), and the PC scatterplots (not shown), indicates that only the first 5 PCs show evidence of substructure. Consistent with this, PLINK results with 5 or 10 PCs were nearly identical. The Q–Q plots for all PLINK analyses showed no sign of inflation, the genomic control factor lambda being <1.03 in all cases. To account for multiple testing, we also applied (using MATLAB47) a global FDR50 test across all traits and SNPs (Supplementary Table 5). To account for the possibility that cryptic relatedness among the individuals studied could affect the linear regression results, we also performed a GWAS using mixed-effects regression models, as implemented in FastLMM13. In this approach, the GRM again specifies the variance of a random effect (other aspects of the regression being as for the simpler model used by PLINK). Results from these random-effect regressions were similar to those obtained in the primary PLINK analyses (Supplementary Table 4). To consider the correlation between pinna traits, we performed a GWAS combining all traits in a single analysis using a multivariate regression model as implemented in MULTIPHEN14 on an LD-pruned data set (Supplementary Fig. 5). In this approach, a SNP genotype is taken as the dependent variable and all phenotypes are jointly taken as covariates. Due to this increased complexity the runtime per SNP is considerably longer, so an LD-pruned subset of 189,707 SNPs was used for this analysis (ensuring that all genome-wide or suggestive SNPs from the primary analyses are included). A meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 6; Supplementary Fig. 6) was carried out for each of the traits by performing a GWAS separately in each country sample (using PLINK as above) and combining the results in METAL15. Forest plots were produced with MATLAB combining all regression coefficients and s.e. Cochran's Q-statistic was computed for each trait to test for effect size heterogeneity across country samples. Prediction of trait phenotypes from genotypes at the seven index SNPs identified in the primary GWAS analysis (Table 1) was performed in MATLAB47 using linear regression and nonlinear neural network models51 (Supplementary Table 7).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization of mouse embryos

Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C overnight, dehydrated to methanol, rehydrated, treated with proteinase K, refixed and hybridized to a digoxigenin-labelled cRNA covering the entire Edar transcript (AF160502). Hybridization was performed in 50% formamide, 750 mM NaCl, 75 mM Na3C6H5O7, 1% SDS containing 50 μg ml−1 yeast RNA and 50 μg ml−1 heparin at 65 °C overnight. After washing and blocking of embryos in 10% sheep serum, the signal was detected using 1/2,000 sheep anti-digoxigenin conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (sheep anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase antibody: 11093274910, Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) followed by NBT (nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride) and BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate p-toluidine) staining in 100 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% Tween 20.

Animals and sample collection

Animal studies were reviewed and approved by The Roslin Institute Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body. The humane care and use of mice (Mus musculus) in this study was carried out under the authority of the appropriate UK Home Office Project License. Forty-two mouse head samples, 18 male and 24 female, were included in the analysis aggregating over four genotype categories. All mice were on the FVB/N strain background. The loss-of-function EdardlJ line carries the downlessJackson allele, encoding Edar p. E379K. The gain-of-function EdarTg951 line carries ∼16 copies of the entire Edar locus on a 200-kb yeast artificial chromosome (thus, homozygous transgenic animals carry about 34 copies of the gene in total)17. Homozygous transgenic animals were used in this study. Fourteen- and 15-day-old animals were weighed and culled by intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbitone. After measurement of body length, heads were depilated using Veet cream (Reckitt Benckiser, Slough, UK), rinsed with water and stored in 2% formaldehyde in PBS.

The variation in age and sex helped to collect animals of more diverse weights and sizes, so that we could control more readily for effects of size and weight on pinna shape. Photographs of superior and lateral views of the head were taken and were blinded prior to landmarking for analysis. A scale was included in the photographs for calibration. Landmark homology across specimens was achieved by controlling the head orientation in all photos (for example, by placing the sagittal plane of the head orthogonal to the anterior–posterior axis of the camera lens). This fixed orientation avoids rolling, heading and pitching rotations and guarantees the coplanarity of landmarks placed on the pinnae (see below).

Mouse pinna phenotyping

Overall, pinna shape variation was examined using geometric morphometric techniques52. Twenty-seven landmarks and semilandmarks (depicted in Supplementary Fig. 8) were digitized, scaled and processed using TPSDig and TPSUtil (http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/). Semilandmarks were placed along the contour of the pinna and other contours of interest, and the TPSRelW (http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/) routine was used to allow semilandmarks to slide so as to minimize bending energy. Reliability of pinna landmarking was evaluated by scoring the same landmarks by a second rater and examining the variation (Supplementary Table 10). Generalized procrustes analysis was used to remove the effects of translation, rotation and scaling52. After superimposition of the generalized procrustes analysis-adjusted landmark coordinates, only the shape component remained in the aligned specimens. The superimposed coordinates were exported to the software MorphoJ53 to obtain PCs of shape. Ear protrusion was defined in two ways: angle between the two protruding pinnae, and distance between the two pinnae tips as a proportion of head width (Supplementary Fig. 9). The effect of Edar genotype on pinna shape and protrusion was tested using multivariate regression analysis in R54, adjusting for age, sex, body length, body weight, head length and head width. Two regression models were tested using two different genotype encodings (Supplementary Note 1): one with four distinct genotype categories and one considering genotypes as a binary variable, based on the notion that the Edar loss-of-function homozygous genotype (EdardlJ/EdardlJ) is recessive.

Human tissue culture for the CART1-binding assay

The human hepatoma Huh7 (ECACC, UK) cell line was grown in high-glucose DMEM (PAA) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Nuclear extracts were obtained from Huh7 cells using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents Kit (Pierce, USA) as described in the manual, with the addition of Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche, UK) to buffers CER I and NER I.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Probe sequences:

rs17023457 T>C

rs17023457 T forward 5′-ACTAACTAATCAACATTCCTTTGCGAATACA-3′

rs17023457 T reverse 5′-TGTATTCGCAAAGGAATGTTGATTAGTTAGT-3′

rs17023457 C forward 5′-ACTAACTAATCAACACTCCTTTGCGAATACA-3′

rs17023457 C reverse 5′-TGTATTCGCAAAGGAGTGTTGATTAGTTAGT-3′

CART1 consensus F 5′-CCACATAATTACATTATCTTG-3′

CART1 consensus R 5′-CAAGATAATGTAATTATGTGG-3′.

Probes were labelled using the Biotin 3′-End DNA Labelling Kit (Pierce) as described in the manufacturer's manual. Binding reactions consisted of 2 μl 10 × binding buffer (100 mM Tris, 500 mM KCl; pH 7.5), 1 μg p[dI-dC], 200 fmol biotin-labelled DNA, made to a total of 20 μl with H2O and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min, followed by the addition of 5 × loading buffer. Competition reactions were performed with 30-min incubation on ice, prior to addition of labelled probes, using 100 × CART1 cold-competitor oligonucleotides. Samples were run on 6% polyacrylamide gel, electrophoresed for 150 min at 120 V.

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter vectors were based on the pGL3 Promoter vector (Promega), with a 872-bp genomic sequence surrounding rs17023457 (Supplementary Fig. 11c) inserted upstream of the SV40 promoter in both orientations using the following primers designed for the InFusion PCR Cloning kit (Clontech):

Forward

Ear1FF: 5′-TCTATCGATAGGTACCCATCTACGGGTCTGGAGGAG-3′

Ear1FR: 5′-GATCGCAGATCTCGAGAGCTCATCCAAGGTCCCAAA-3′

Reverse

Ear2RF: 5′-GATCGCAGATCTCGAGCATCTACGGGTCTGGAGGAG-3′

Ear2RR: 5′-TCTATCGATAGGTACCAGCTCATCCAAGGTCCCAAA-3′.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuickChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) as detailed in the manual, using the following oligonucleotide sequences (designed for reverse strands):

Primer name; primer sequence (5′–3′)

SDMFFC 5′-GTATTCGCAAAGGAGTGTTGATTAGTTAGTGGTCGGTATCAT-3′

SDMFRC 5′-ATGATACCGACCACTAACTAATCAACACTCCTTTGCGAATAC-3′

Primer name; primer sequence (5′–3′)

SDMRFG 5′-GACCACTAACTAATCAACACTCCTTTGCGAATACAGCTTCAG-3′

SDMRRG 5′-CTGAAGCTGTATTCGCAAAGGAGTGTTGATTAGTTAGTGGTC-3′

All constructs were verified by direct sequencing.

Huh7 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 per well, in a 96-well plate and grown to confluence overnight in the appropriate media (described above). Cells were transfected with 250 ng pGL3 reporter construct, with 10 ng pRLTK as a transfection control. Transfection was carried out in Opti-Mem serum-free media (Sigma, UK) using Lipofecamine 3000 (Invitrogen) as described in the manual. Media was replaced 24 h following transfection, with serum-containing media described above, and the cells left for 2 days before harvesting. Cells were lysed using Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) and luciferase expression was determined using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega), and measured in the Tropix TR717 Microplate Luminometer (PE Applied Biosystems, UK). For each construct used, the transfection assay was performed using 12 wells of a 96-well plate and the mean luciferase reading reported. The experiment was repeated in triplicate using fresh vector preparations. Analysis of variance was performed to compare the effect of the T and C alleles on the luciferase readings, taking into account the variability across replicates and wells.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Adhikari, K. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies multiple loci for variation in human ear morphology. Nat. Commun. 6:7500 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8500 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-11, Supplementary Tables 1-10, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank the volunteers for their enthusiastic support. We also thank Alvaro Alvarado, Mónica Ballesteros Romero, Mari-Wyn Burley, Ricardo Cebrecos, Debajyoti Choudhury, Miguel Ángel Contreras Sieck, Francisco de Ávila Becerril, Joyce De la Piedra, María Teresa Del Solar, Paola Everardo Martínez, William Flores, Martha Granados Riveros, Wendy Hart, Ilich Jafet Moreno, Jodie Lampert, Mowmita Basak Mow, Paola León-Mimila, Javier Mendoza, Francisco Quispealaya, Diana Rogel Diaz, Ruth Rojas, Norman Russell, Vanessa Sarabia and Fabienne Tessiot for assistance with volunteer recruitment, sample processing and data entry. We are very grateful to the institutions that kindly provided facilities for the assessment of volunteers, including: Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (Mexico); Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Universidad de Lima and Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Peru). This work was funded by grants from the Leverhulme Trust (F/07 134/DF to A.R.-L.), BBSRC (BB/I021213/1 to A.R.-L. and Institute Strategic Programme grant to The Roslin Institute), Universidad de Antioquia (GENMOL sostenibilidad 2015–2016 and MASO 2013–2014). S.E.H. holds a British Heart Foundation Chair and acknowledges funding from grant RG008/08 and is also supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. A.J.P.S. is funded by a BHF Fellowship (FS/13/6/29977).

Footnotes

Author contributions K.A., A.J.P.S., M.Q.-S., J.R., M.C., M.F.B., R.G.-J., D.H., D.B. and A.R.-L. conceived and designed the study. K.A., V.A.-A., C.J., W.A., M.F., M.P., G.M.P., R.B.L., J.G.-V., H.V.-R., T.H., V.R., C.C.S.d.C., V.G., M.H., V.V. and D.H. contributed reagents/material. G.R., A.J.P.S., E.K., J.P., M.Q.-S., M.C., D.H., K.A., V.A.-A., C.J., W.A., M.F., M.P., G.M.P., R.B.L., J.G.-V., H.V.-R., T.H., V.R., C.C.S.d.C., V.G., M.H. and V.V. performed experiments. K.A., A.J.P.S., M.Q.-S., M.C., D.H. and A.R.-L. analysed data. V.A.-A., J.G.-V., C.G., G.P., L.S.-F., F.M.S., M.-C.B., S.C.-Q., F.R., G.B., R.C., J.R., M.C., K.A., S.E.H., R.G.-J., D.H., D.B. and A.R.-L. supervised research/PI. K.A. and A.R.-L. wrote the manuscript. A.J.P.S., C.G., G.P., S.C.-Q., J.R., M.C., M.F.B., R.G.-J., D.H. and D.B. critically revised the manuscript.

References

- Gleeson M. J. & Clarke R. C. Scott-Brown's Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery CRC Press (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Cox T. C., Camci E. D., Vora S., Luquetti D. V. & Turner E. E. The genetics of auricular development and malformation: new findings in model systems driving future directions for microtia research. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 57, 394–401 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azaria R., Adler N., Silfen R., Regev D. & Hauben D. J. Morphometry of the adult human earlobe: a study of 547 subjects and clinical application. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 111, 2398–2402 discussion 2403–2404 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sforza C. et al. Age- and sex-related changes in the normal human ear. Forensic Sci. Int. 187, 110 e1–110 e7 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K. S., Stott D. J., Sivakumar B. & Kang N. A morphometric study of the human ear. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 64, 41–47 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoux M. et al. Mouse Hoxa2 mutations provide a model for microtia and auricle duplication. Development 140, 4386–4397 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Linares A. et al. Admixture in latin america: geographic structure, phenotypic diversity and self-perception of ancestry based on 7,342 individuals. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004572 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed D., Hemani G., Johnson M. R. & Balding D. J. Improved heritability estimation from genome-wide SNPs. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 1011–1021 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Lee S. H., Goddard M. E. & Visscher P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson E. A. Maximum likelihood estimation of human craniometric heritabilities. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 131, 169–180 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Abadias N. et al. Heritability of human cranial dimensions: comparing the evolvability of different cranial regions. J. Anat. 214, 19–35 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippert C. et al. FaST linear mixed models for genome-wide association studies. Nat. Methods 8, 833–835 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly P. F. et al. MultiPhen: joint model of multiple phenotypes can increase discovery in GWAS. PLoS ONE 7, e34861 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer C. J., Li Y. & Abecasis G. R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26, 2190–2191 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headon D. J. et al. Gene defect in ectodermal dysplasia implicates a death domain adapter in development. Nature 414, 913–916 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou C. et al. Enhanced ectodysplasin-A receptor (EDAR) signaling alters multiple fiber characteristics to produce the East Asian hair form. Hum. Mutat. 29, 1405–1411 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk J. et al. Positive selection in East Asians for an EDAR allele that enhances NF-kappaB activation. PloS ONE. 3, e2209 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola M. L. Molecular aspects of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 149 A, 2031–2036 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto A. et al. A scan for genetic determinants of human hair morphology: EDAR is associated with Asian hair thickness. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 835–843 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto A. et al. A replication study confirmed the EDAR gene to be a major contributor to population differentiation regarding head hair thickness in Asia. Hum. Genet. 124, 179–185 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura R. et al. A common variation in EDAR is a genetic determinant of shovel-shaped incisors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85, 528–535 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. H. et al. Effects of an Asian-specific nonsynonymous EDAR variant on multiple dental traits. J. Hum. Genet. 57, 508–514 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. et al. The adaptive variant EDARV370A is associated with straight hair in East Asians. Hum. Genet. 132, 1187–1191 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamberov Y. G. et al. Modeling recent human evolution in mice by expression of a selected EDAR variant. Cell 152, 691–702 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monreal A. W. et al. Mutations in the human homologue of mouse dl cause autosomal recessive and dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Nat. Genet. 22, 366–369 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M. K. et al. The T-box transcription factor Tbx15 is required for skeletal development. Mech. Dev. 122, 131–144 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry G. A. Genetical and development studies on droopy-eared mice. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 7, 39–65 (1959). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candille S. I. et al. Dorsoventral patterning of the mouse coat by Tbx15. PLoS Biol. 2, E3 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lausch E. et al. TBX15 mutations cause craniofacial dysmorphism, hypoplasia of scapula and pelvis, and short stature in Cousin syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 83, 649–655 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu S., Tucker S. C., Zhao Q., deCrombrugghe B. & Wisdom R. Physical and genetic interactions between Alx4 and Cart1. Development 126, 359–369 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima M. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies four susceptibility loci for keloid in the Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 42, 768–771 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits P. et al. Mutation in mitochondrial ribosomal protein MRPS22 leads to Cornelia de Lange-like phenotype, brain abnormalities and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 394–399 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beysen D. et al. Deletions involving long-range conserved nongenic sequences upstream and downstream of FOXL2 as a novel disease-causing mechanism in blepharophimosis syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77, 205–218 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haene B. et al. Disease-causing 7.4 kb cis-regulatory deletion disrupting conserved non-coding sequences and their interaction with the FOXL2 promotor: implications for mutation screening. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000522 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimoin D. L. & Emery A. E. H. Emery and Rimoin's Principles and Practice of Medical Genetics 5th edn Churchill Livingstone (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Weidinger G., Thorpe C. J., Wuennenberg-Stapleton K., Ngai J. & Moon R. T. The Sp1-related transcription factors sp5 and sp5-like act downstream of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesoderm and neuroectoderm patterning. Curr. Biol. 15, 489–500 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunty W. C. Jr., Kennedy M. W., Chalamalasetty R. B., Campbell K. & Yamaguchi T. P. Transcriptional profiling of Wnt3a mutants identifies Sp transcription factors as essential effectors of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in neuromesodermal stem cells. PLoS ONE 9, e87018 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettre G. et al. Identification of ten loci associated with height highlights new biological pathways in human growth. Nat. Genet. 40, 584–591 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson D. F. et al. Many sequence variants affecting diversity of adult human height. Nat. Genet. 40, 609–615 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soranzo N. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide scans for human adult stature identifies novel Loci and associations with measures of skeletal frame size. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000445 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. N. & Ross C. F. Primate auditory diversity and its influence on hearing performance. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol 281, 1123–1137 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. N. & Colbert M. W. Correlations between auditory structures and hearing sensitivity in non-human primates. J. Morphol. 271, 511–532 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D. The Evolution of the Human Head Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Abaza A., Ross A., Herbert C., Harrison M. A. F. & Nixon M. S. A survey on ear biometrics. ACM Comput. Surv. 45, 1–35 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Junod S., Pasquier J. & Champod C. The development of an automatic recognition system for earmark and earprint comparisons. Forensic Sci. Int. 222, 170–178 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The MathWorks,. Inc. MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox Release 2013b The MathWorks, Inc. (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Shrout P. E. & Fleiss J. L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 86, 420–428 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D. H., Novembre J. & Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudoit S. & Laan M. J. V.D. Multiple Testing Procedures with Applications to Genomics Springer (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T., Tibshirani R. & Friedman J. H. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction 2nd edn Springer (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zelditch M. L., Swiderski D. L., Sheets H. D. & Fink W. L. Geometric Morphometric for Biologists Elsevier (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg C. P. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11, 353–357 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Adobe Photoshop CS6 Adobe Systems Incorporated (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pruim R. J. et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics 26, 2336–2337 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. C., Fry B., Maller J. & Daly M. J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21, 263–265 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-11, Supplementary Tables 1-10, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References