Vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) can cause vision loss and preclude panretinal photocoagulation (PRP).1 The DRCR.net investigated whether intravitreal ranibizumab compared with intravitreal saline had a beneficial effect on the vitrectomy rates of eyes with vitreous hemorrhage from PDR precluding complete PRP. Eyes were randomly assigned to 0.5mg ranibizumab (N=125) or saline (N=136), which were injected into the vitreous, at baseline, 4 and 8 weeks.2 The primary endpoint was assessed at 16 weeks, for safety purposes participants were followed for 52-weeks. It should be noted, after 16-weeks, participant’s management was at investigator’s discretion.

As previously reported, by the 16-week endpoint the cumulative probability of vitrectomy was 12% for eyes assigned to ranibizumab compared with 17% for saline (difference 4%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −4% to +13%),2 suggesting little likelihood of a clinically important difference. The study did not address whether ranibizumab or saline injections were superior to observation alone. Previously reported secondary outcomes suggested a short-term positive biologic effect of ranibizumab compared with saline: (1) the ability to complete PRP without vitrectomy by 16 weeks was 44% with ranibizumab versus 31% with saline group (P=0.05), (2) mean visual acuity improvement from baseline to 12 weeks was 22±23 letters with ranibizumab versus 16±31 letters with saline (P=0.04), and (3) recurrent vitreous hemorrhage within 16 weeks occurred in 6% of eyes with ranibizumab compared with 17% with saline (P=0.01). No short-term safety concerns were noted. The objective of this report is to present the one-year follow-up results to the original study.

Results

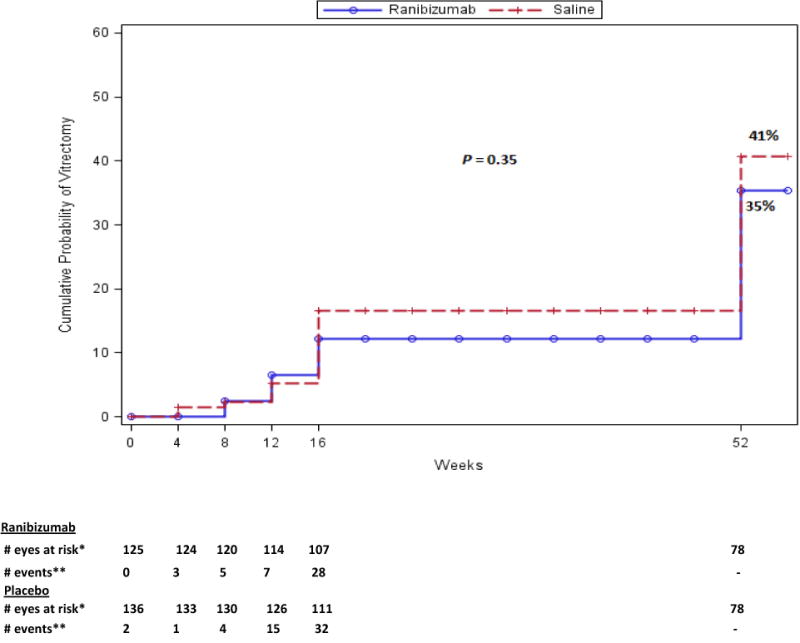

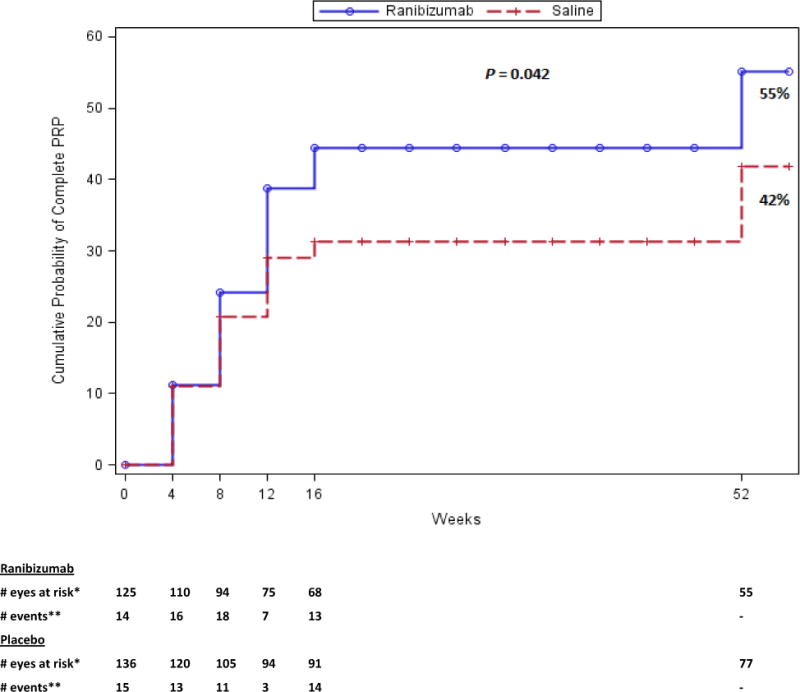

Overall, 82% of the participants completed a 52 week visit, 2% died, and 16% were lost to follow-up. The one-year cumulative probability of vitrectomy was 35% for the ranibizumab group versus 41% for the saline group (difference 5%, 95% CI: −7% to 17%; [P=0.35]), Figure 1). The combined one-year cumulative probability of vitrectomy in both groups was 38% (CI: 32% to 44%). The cumulative probability of complete PRP by the 52-week visit was 55% for ranibizumab versus 42% for the saline group (P=0.042) (Figure 2). The mean visual acuity (± SD) letter score (approximate Snellen equivalent) at 52 weeks was 65±22 (20/50 ± 4.4 lines) in the ranibizumab group versus 64±26 (20/50 ± 5.2 lines) in the saline group (P=0.83). Between 16 and 52 weeks of follow-up, 17 eyes in the ranibizumab group received 34 anti-VEGF injections, 31 eyes in the saline group received 46 anti-VEGF injections. Following the 16-week endpoint, investigator-reported recurrent vitreous hemorrhage appeared similar between treatment groups; 13 of 102 eyes in the ranibizumab group and 15 of 113 eyes in the saline group. Post 16 weeks, traction and/or rhegmatogenous retinal detachments on clinical exam or ultrasound were seen in 7 eyes in the ranibizumab group compared with 11 eyes in the saline group. Three (2%) participants in the ranibizumab group and 8 participants (6%) in the saline group had an Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration defined systemic adverse event (P=0.22).

Figure 1. Cumulative Probability of Vitrectomy Surgery by 52 Weeks of Study Follow-up.

Categorization of events and censoring into intervals was defined by visit date if the visit occurred, otherwise using the target date of the visit.

* Number of eyes with follow up data at the start of the interval, and no vitrectomy prior to the start of the interval.

** Number of eyes with vitrectomy during the subsequent 4-week period.

† Not to scale.

No follow-up contact was performed between 16 and 52 weeks.

Figure 2. Cumulative Probability of Complete PRP by 16 Weeks of Study Follow-up.

Categorization of events and censoring into intervals was defined by visit date if the visit occurred, otherwise using the target date of the visit.

Eyes with vitrectomy were censored in the interval the surgery occurred.

*Number of eyes with follow up data at the start of the interval, and with no complete PRP prior to the start of the interval.

** Number of eyes with complete PRP during the subsequent 4-week period.

†Not to scale.

No follow-up contact was performed between 16 and 52 weeks.

Conclusions

Over one-third of eyes enrolled in the study underwent vitrectomy in both groups by one year. The ability to perform panretinal photocoagulation occurred more frequently in the ranibizumab group; however the greater improvement in mean visual acuity observed at 12 weeks was not present at 52-weeks. By the 52-week visit, there were no apparent differences on safety outcomes between the two interventions.

The evaluation of intravitreal saline versus ranibizumab given at baseline, 4 and 8 weeks after randomization in eyes with vitreous hemorrhage, showed no difference in safety between the two treatment groups at 52-weeks. The absence of any clinically relevant differences in rates of vitrectomy noted through the primary endpoint at 16 weeks persisted through the 52-week safety follow-up.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Neil M. Bressler, MD of Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, made substantial contributions to this manuscript including conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critical revision for important intellectual content.

Adam R. Glassman, Corresponding author, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis as well as the decision to submit for publication.

Financial Support: Supported through a cooperative agreement from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services EY014231, EY018817, EY023207. Genentech provided the ranibizumab study drug for this trial and funds to the DRCR.net to defray the study’s clinical site costs.

The funding organization (National Institutes of Health) participated in oversight of the conduct of the study and review of the manuscript but not directly in the design or conduct of the study, nor in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Financial Disclosures: Complete lists of all DRCR.net investigator and writing committee financial disclosures are available at www.drcr.net.

References

- 1.Kempen JH, O’Colmain BJ, Leske MC, et al. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 Apr;122(4):552–563. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diabetic Retinopathy Clincical Research Network. Randomized clinical trial evaluating intravitreal ranibizumab or saline for vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Mar;131(3):283–293. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]