We read Green, de la Haye, Tucker & Golinelli’s paper, ‘Shared risk: who engages in substance use with American homeless youth?’ (hereafter RAND) [1], with great interest and appreciation, both for its rigor and potential impact. We would like to open a friendly dialogue about the implementation of network-based prevention for homeless youth. We believe that these results and the results of others suggest that popular opinion leader interventions are not an advisable network-based strategy.

There is a great desire both among academics [2-11] and our community-based collaborators to utilize network-based prevention programs to reduce risk taking among homeless youth. This interest is driven by the relatively low cost of these programs, coupled with an understanding that such programs might engage homeless youth who are transient, hidden and distrustful of adults. This represents an exciting convergence around the desirability and probable acceptability of network based prevention. What remains unclear is how and with whom to implement these programs.

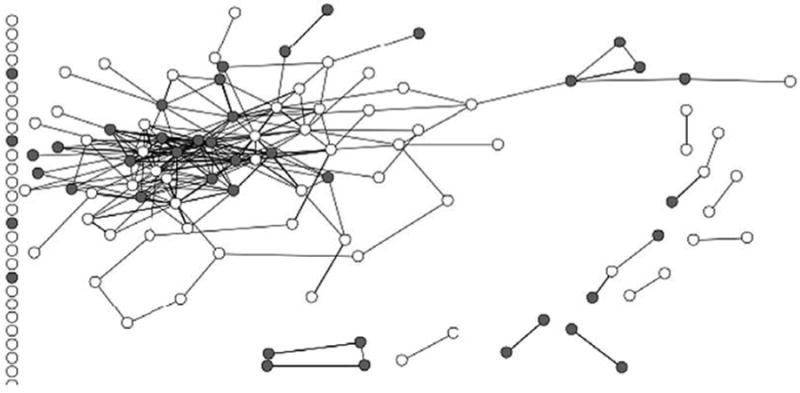

RAND present fascinating results indicating that opinion leaders and popular peers are among those with whom youth are most likely to drink and use drugs. RAND recognize the complexity of recruiting substance using opinion leaders for interventions to reduce substance use, but suggest that these peers may still be appropriate people to train as peer leaders. We respectfully question this interpretation. It is entirely possible that these popular and respected peers are popular and respected because of their participation in risky behaviors. Being popular and respected often requires adhering to the norms and values of a network—in this case a network for whom risk-taking is normative. Thus, it is possible that asking youth to curb or abandon risk behaviors could compromise the popularity and respect they hold. As an illustrative example, Fig. 1 shows that substance-using youth are not only popular within egocentric networks of youth (as RAND have shown), but also occupy central positions within sociometric networks of homeless youth, lending further evidence to the hypothesis that risky behavior might be an important component of popularity for homeless youth. Given the often tenuous nature of social standing among homeless youth, we are wary of the practical efficacy of attempting to change norms that may confer status among this population.

Figure 1.

Sociometric data on life-time methamphetamine use (in grey) among homeless youth, Holllywood, CA, 2008 (n = 136)

RAND also suggests that targeting ‘risky dyads’ could be important for maintaining successful behavior change. This is probably true; however, we believe that their results suggest another type of relationship where dyadic-level interventions could be even more successful. They indicate that dyads where use is less likely are family ties and relationships not formed on the streets. These findings are consistent with the results regarding positive influences of family-based and home-based relationships seen in other data sets (e.g. [7,12]). We suggest that these home- and family-based dyads are the most appropriate targets of intervention efforts for homeless youth. Naturally, these relationships tend to be discouraging of use. An intervention model targeting family and home-based dyads does not yet exist, but the work of RAND, as well as others in this area, would suggest that this approach may be most efficacious.

The creation and/or implementation of network based prevention for homeless youth should be a high priority. Models which rely too heavily on popular opinion leaders and high popularity peers seem to us to be a poor choice. A new set of models that expand upon the influences of positive adults, family and positive home-based peers seems to be the most appropriate focus of intervention efforts. We truly appreciate the RAND efforts and the opportunity with which their work has provided us to begin to have this dialogue about peer-based prevention in a public forum.

Acknowledgments

The data in Fig. 1 are drawn from research funded by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH R01093336.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

None.

References

- 1.Green H, de la Haye K, Tucker J, Golinelli D. Shared risk: who engages in substance use with American homeless youth? Addiction. 2013;108:1618–24. doi: 10.1111/add.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold EM, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Comparisons of prevention programs for homeless youth. Prev Sci. 2009;10:76–86. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0119-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mallett S, Rosenthal D. The effects of peer-group network properties on drug use among homeless youth. Am Behav Sci. 2005;48:1102–23. doi: 10.1177/0002764204274194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Pro-social and problematic peer influences on HIV/AIDS risk behaviors among newly homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS Care. 2007;19:697–704. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice E, Stein JA, Milburn N. Countervailing social network influences on problem behaviors among homeless youth. J Adolesc. 2008;39:625–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice E. The positive role of social networks and social networking technology in the condom using behaviors of homeless youth. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:588–95. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice E, Milburn NG, Monro W. Social networking technology, social network composition, and reductions in substance use among homeless adolescents. Prev Sci. 2011;12:80–8. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice E, Barman-Adhikari A, Milburn NG, Monro W. Position-specific HIV risk in a large network of homeless youth. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:141–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker JS, Hu J, Golinelli D, Kennedy DP, Green HD, Jr, Wenzel SL. Social network and individual correlates of sexual risk behavior among homeless young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:386–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy DP, Tucker JS, Green HD, Jr, Golinelli D, Ewing B. Unprotected sex of homeless youth: results from a multilevel dyadic analysis of individual, social network, and relationship factors. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2015–32. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Golinelli D, Green HD, Zhou A. Personal network correlates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among homeless youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyler KA. Social network characteristics and risky sexual and drug related behaviors among homeless young adults. Soc Sci Res. 2008;37:673–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]