SYNOPSIS

Clinical practice guidelines endorse the use of palliative care in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Palliative care is no longer seen as “giving up” or “accepting death,” but is now conceptualized as “supportive care” afforded to most patients with chronic, life-limiting illness. However, the optimal content and delivery of palliative care interventions remains unknown and its integration into existing heart failure disease management continues to be a challenge. Therefore, we will comment on the current state of multidisciplinary care for such patients, explore evidence supporting a team-based approach to palliative and end-of-life care for patients with heart failure, and identify high-priority areas for research. Ultimately, patients require a “heart failure medical home”, where various specialties may take a more central role in coordination of patient care at different times in the disease span, sometimes transitioning leadership from primary care to cardiology to palliative care.

Keywords: Palliative care, Hospice care, Heart failure, Interdisciplinary communication, Patient care team, Comprehensive health care

INTRODUCTION

Among an estimated 5.1 million Americans with heart failure, the prevalence of advanced disease is 5 to 10%.1 As such, nearly half a million Americans struggle with significant symptom burden, psychosocial stressors, and difficult decisions imposed by their end-stage heart failure. Disease prevalence is expected to grow 25% by 2030 due primarily to improved survival, while costs are projected to balloon from $32 billion in 2013 to $70 billion in 2030.1 With increased emphasis on patient-centered care,2,3 and in the face of unsustainable health care expenditures, there has been increasing attention placed on palliative and end-of-life care for patients with advanced heart failure.4

The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines support the use of palliative care in patients with end-stage heart failure as level 1B.4 Medicare’s 2014 update to National Coverage Determination for mechanical circulatory support (MCS) even mandates a “multidisciplinary team” that includes a “palliative care specialist.5” However, there is limited evidence to guide the content, implementation, and integration of palliative care interventions into existing heart failure disease management. Therefore, we will explore evidence supporting a team-based approach to palliative and end-of-life care for patients with heart failure, comment on the current state of multidisciplinary care for such patients, identify knowledge gaps, and discuss opportunities for future study.

“Team-Based” Care Implies a Multidisciplinary Approach

Ample evidence exists supporting team-based care for patients with heart failure to decrease rehospitalizations and improve survival through education, structured follow-up, patient self-care, and careplan adherence.6,7 However, few pilot studies have assessed the efficacy of multidisciplinary palliative care in improving outcomes germane to end-stage heart failure (i.e., quality of life, symptom control, decreased healthcare utilization, lower financial and caregiver burden). This is in part due to heterogeneity in defining what palliative care is and how it should be delivered. Table 1 details selected clinical trials and intervention studies that support a multidisciplinary palliative approach by incorporating specialties tailored to patient needs to facilitate the inevitable transitions in chronic heart failure care.

Table 1.

Selected clinical trials and intervention studies of team-based palliative care in heart failure

| Study | Study Type | Setting/Subject | Provider Training | Intervention Domains | Intervention Components |

Intervention Development |

Team Members (Team Liaison in bold) |

Outcomes/ Results |

Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aiken 20068 |

Prospective, Single Center, Randomized Controlled Trial (Blinded Enrollers & Interviewers) |

Home-based COPD or NYHA IIIb/IV HF, prognosis ≤ 2 yrs n = 190 (129 HF) 100 case (67 HF) 90 control (62 HF) |

|

|

PhoenixCare Model

|

– – |

RN Case Manager Medical Director SW Chaplain PCP Family Community Agencies |

Among cases:

|

|

| Bekelman 20149 |

Prospective, Single Center, Mixed-Methods Feasibility Pilot |

Outpatient HF (82% NYHA II/III) n = 17 |

|

|

CASA(Collaborative Care to Alleviate Symptoms & Adjust to Illness)

|

|

PCP RN SW Psychologist Cardiologist PCS |

|

|

| Brannstrom 201410 (Sweden) |

Prospective, Single Center, Randomized Controlled Trial |

Home-based NYHA III/IV HF n = 72 36 case 36 control |

– – |

|

PREFER(Palliative advanced home caRE and heart FailurE caRe)

|

|

PCS HF Cardiologist Cardiologist HF RN PC RN PT/OT |

Among cases:

|

|

| Dionne- Odom11 2014 |

Prospective, Single Center Feasibility Pilot |

Community- based/Rural HF (86% NYHA III/IV) n = 11 dyads (patient/caregiver) |

|

|

ENABLE(Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends):PC-CHF

|

|

AP PC RN Coach Caregiver PCP Internist Cardiologist |

|

|

| Enguidanos 200512 |

Prospective, Controlled Trial |

Home-based HF, COPD, Cancer prognosis ≤ 1 yr n = 298 (82 HF) 159 case (31 HF) 139 control (51 HF) |

|

|

KPPC(Kaiser Permanente Palliative Care)

|

|

Family RN MD SW |

Among cases:

|

|

| Evangelista 201213 |

Prospective, Single Center, Cohort Study |

Outpatient NYHA II/II HF, hospitalized n = 36 |

– – |

|

|

– – | PCS or PC NP |

|

|

| Evangelista 201414 |

Prospective, Single Center, Cohort Study |

Outpatient NYHA II/III HF, hospitalized n = 42 29 ≥ 2 PC visits 13 < 2 PC visits |

– – |

|

|

– – | PCS or PC NP |

|

|

| Schellinger 201115 |

Prospective, Multi-site/ Single System Implementation Study |

Outpatient HF, referred for ACP n = 1894 602 completed ACP 1292 did not |

|

|

“Respecting Choices:” Disease- Specific ACP

|

|

Certified Facilitator Caregiver/Proxy RN SW Referral Coordinator |

|

|

| Schwarz 201216 |

Retrospective, Single Center Descriptive Study |

Inpatient NYHA IV HF, referred for transplant & early PC n = 20 |

– – |

|

|

– – | PCS HF Cardiologist NP SW Psychiatrist Hospital Chaplain |

|

|

| Wong 201317(China) |

Retrospective, Single Center Descriptive Study |

Home-based NYHA III/IV HF n = 44 |

– – |

|

|

|

MD RN Counselor |

|

|

COPD - chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF - heart failure; NYHA - New York Heart Association; PC - palliative care; ACP - advance care planning; EOLC - end of life communication; RN - registered nurse; Psych - psychologist; MD - medical doctor; NP - nurse practitioner; SW - social work; PCP - primary care physician; AP - advanced practice; PCS - palliative care specialist; CAD - coronary artery disease; ESC - European Society of Cardiology; IM - internal medicine; RCT - randomized controlled trial; ED - emergency department; PT - physical therapy; OT - occupational therapy; KCCQ - Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; AD - advance directive; prn – as needed; QoL – quality of life; yr – year

What’s in the Name? “Palliative Care” is “Supportive Care”

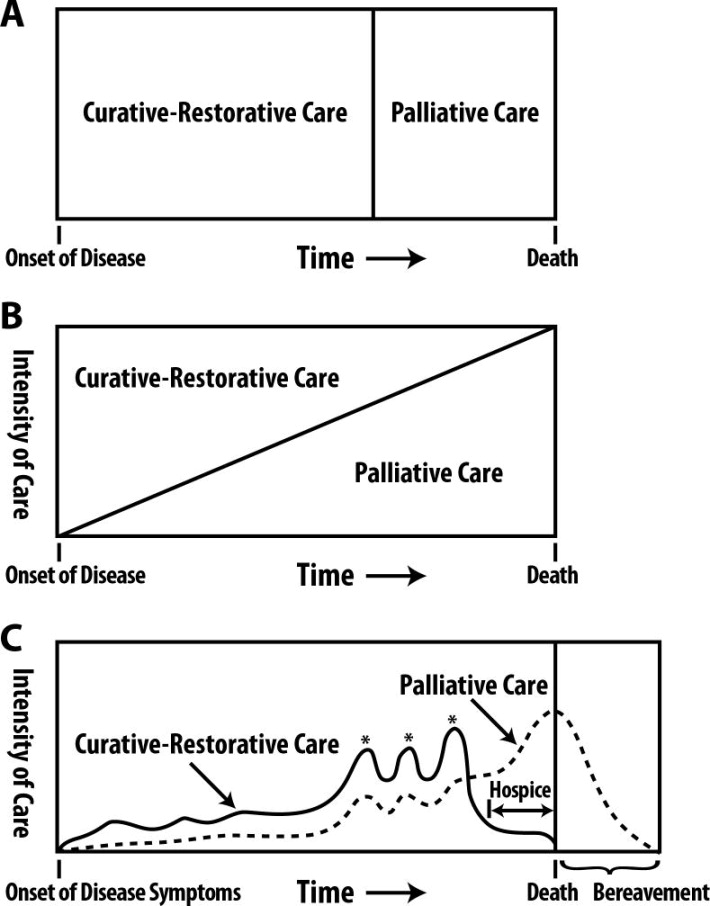

Historically, the term “palliative care” had been conflated with hospice care—a focused approach to dying patients for whom disease-targeted treatment or cure are no longer viable. However, this narrow restriction has given way to a more holistic view of disease management in which “supportive care” is afforded to all patients with chronic or life-threatening illness (Figure 1). Optimal palliative care ideally begins early in the course of the disease and continues in parallel with heart failure-targeted therapy in an integrative, multidisciplinary manner.20–23 Essentially, all healthcare providers should strive to treat the whole patient collaboratively with a team of colleagues. Likewise, heart failure clinicians should maintain concurrent foci on treating disease, extending survival and optimizing quality of life for patients with chronic heart failure at all disease stages.

Figure 1. Evolving models of integrating curative-restorative care with palliative care.

A) Previously, curative-restorative care was seen as an “all or none” phenomenon, and palliative care was only initiated once curative-restorative care options were exhausted. B) Palliative care principles were incorporated concurrently with curative-restorative care models, but as less curative-restorative care options existed palliative care was intensified. C) This model accounts for the fact that care trajectories rarely change at a constant, linear slope; rather, care intensity is augmented by punctuated exacerbations of illness over time.

From Lankan PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Apr 15 2008;177(8):912–927; with permission.

Building on Experience or Diverging Pathways? Palliative Care in Cancer and in Heart Failure

Evidence and education have helped to normalize early, integrated palliative care approaches and improve outcomes for patients with advanced cancer.24,25 Due to a dearth of evidence in cardiology literature, heart failure guidelines and consensus statements have partially relied on cancer care studies to recommend best practices for treating patients at end-of-life.4,23 However, despite similar or worse symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being for patients with advanced heart failure compared to those with advanced cancer,26 heart failure has been associated with less access to palliative care and use of hospice, and higher rates of resource utilization and aggressive treatment.27,28 This disparity highlights a need to better inform providers and patients of options for progressive and end-of-life heart failure.

Some have noted that translating the model of palliative cancer care to heart failure may not be feasible or appropriate, given a less predictable course of disease progression and less well-defined transition stages by which to time interventions.23 Even so, evidence-based cancer care provides a foundation from which integrated palliative heart failure care can expand. For example, the ENABLE CHF-PC trial (Table 1) evolved from a series of successful palliative cancer care trials, and its recently published feasibility pilot results were promising.11

THE LOGISTICS OF TEAM-BASED PALLIATIVE CARE IN HEART FAILURE

Who Makes up the Clinical Palliative Care Team?

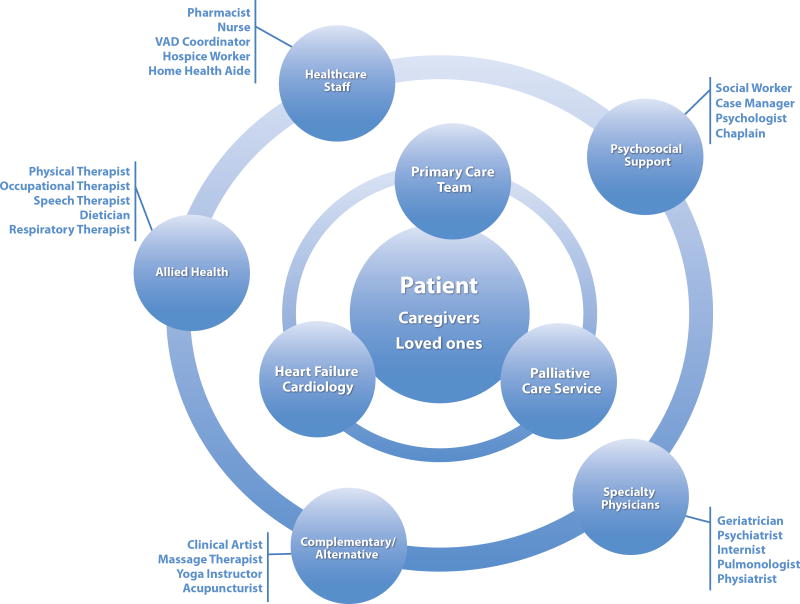

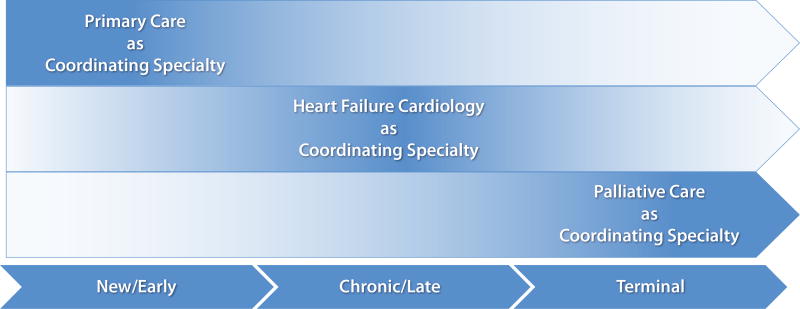

Various healthcare providers from multiple fields comprise the clinical component of a multi-disciplinary palliative care team, along with patients and caregivers (Figure 2). The three main specialties include primary care, cardiology, and palliative care, each represented by various physicians, advanced practitioners, and nurses. A collaborative interface between these specialties leads to improved communication and understanding of patients’ goals, more streamlined referrals to specialists, and better end-of-life experiences.29 Interdisciplinary care increases prescriptions for symptom control medication and decreases hospitalizations, length of stay and cost of care.7 In a sense, these three specialties should constitute the core of the patient’s “heart failure medical home.” Each specialty may take a more central role in coordination of patient care at different times in the disease span (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Layered model of team-based palliative care in heart failure.

This integrated, multidisciplinary model keeps the patient and caregivers central to the plan of care, while supported by layers of clinicians and providers whose support can vary over time. The core clinical team is comprised of primary care, cardiology, and palliative care, with many secondary supportive and consultative services. The included providers are likely partial, and other team members may exist in individual teams to support patients as best as able.

Figure 3. Evolution of central care coordination at different stages of heart failure.

In a team-based approach to advanced heart failure and palliative care, the responsibilty and contribution of each core specialty may grow or decrease as the patient’s disease progresses. This pattern of care coordination would likely differ for all patients, according to their individual trajectory and needs.

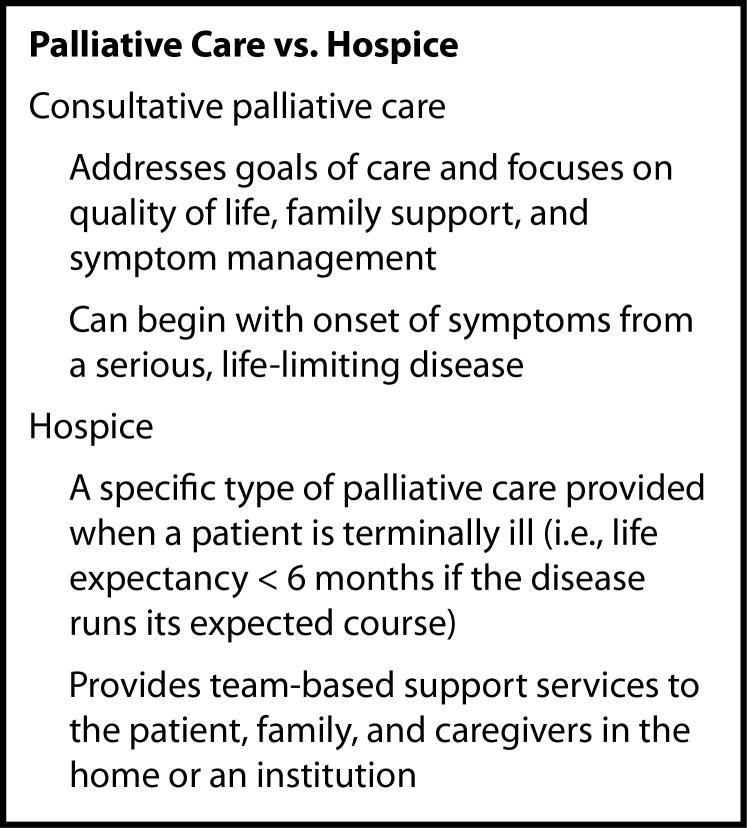

This partnership can be challenging due to prognostic uncertainty, difficulty with optimal timing of consultation, the desire to “save” patients, and the fear of failing them. Such barriers stem from an inaccurate perception of palliative care as synonymous with hospice.30,31 Palliative care should not be seen as “giving up” or “accepting death,” but as one component of a collaborative, supportive approach to patient care (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Palliative care vs. hospice.

Adapted from Swetz KM, Kamal AH. In the clinic. Palliative care. Ann Intern Med. Feb 7 2012;156(3):ITC2-2-ITC2-16; with permission.

However, a national shortage of palliative care specialists exists along with the proliferation of heart failure in older patients with multimorbidity.33 Therefore, a shared-care approach is crucial. By improving clinician skills and allaying fears through interaction with and learning from palliative care specialists, general practitioners and cardiologists can be empowered to provide primary palliative care to their patients with heart failure. Palliative care could then be consulted for more challenging issues, such as complex symptom control or complicated advance care planning.34

Who Takes the Lead?

The role of an appointed clinical team leader, or liaison, is important in coordination of multidisciplinary care.23 The team cannot function effectively without a clear understanding of organizational and leadership structure. Early in disease progression, lead input is more likely to fall to a general practitioner or cardiology service, with palliative care consultation as needed. In end-stage disease, palliative care specialists might take more central ownership of the patient’s care. In a number of studies and palliative care programs, authors described great success in appointing a heart failure or case management nurse to communicate with patients and delegate responsibility for different aspects of care.8,12,35–37 A single team member who acts as the liaison in coordinating primary and referral services thereby offers continuity of care, a reliably recognizable team contact, and a source of trust and comfort for patients. The clinical team leader can assure that medical decision-making is tailored to patients’ values, goals, and preferences.38

Referrals among patients with advanced heart failure are most commonly for allied health services and psychosocial support. Figure 2 includes all team members mentioned previously in controlled trials, pilots or reviews of multi-disciplinary heart failure palliative care programs. Data from two descriptive studies on the frequency of referral types in a single palliative heart failure service is presented in Table 2. The needs of patients with advanced heart failure can be universal, but may also have patient, site, and regional variation. Meeting such patient needs may also challenge financial and staffing sustainability. Fortunately, while the multidisciplinary palliative care team should adopt a holistic, patient-centered perspective, not all patients require all services.

Table 2.

Services accessed in two team-based palliative heart failure programs

| Bekelman 201139 |

Evangelista 201414 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Number of patients | 50 | 36 |

|

| ||

| Study Type | Case Series | Descriptive Study |

|

| ||

| Study Location | Aurora, CO | Irvine, CA |

|

| ||

| Rate of Services Used | ||

|

| ||

| Chaplain | – – | 45% |

|

| ||

| Home Health | – – | 83% |

|

| ||

| Hospice | 16% | 7% |

|

| ||

| Neurology | 4% | – – |

|

| ||

| Other | 10% | |

| Alternative Medicine | 2% | |

| Pain Clinic | 2% | – – |

| Pulmonary Clinic | 2% | |

| Speech Therapy | 2% | |

| Weight Loss Clinic | 2% | |

|

| ||

| Palliative Care Specialist | 100% | 100% |

| Nurse Practitioner | – – | 83% |

| Physician | 27% | |

|

| ||

| Pharmacist | – – | 100%* |

|

| ||

| Physical & Occupational Therapy/Rehabilitation | 20% | 66% |

|

| ||

| Psychiatry | 8% | 55% |

|

| ||

| Psychology/Counseling | 4% | – – |

|

| ||

| Social Work | 26% | 69% |

|

| ||

| Support Groups | – – | 31% |

Mandatory referral

Data from Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Allen LA, Shakar S, Kutner JS, Matlock DD. Outpatient palliative care for chronic heart failure: a case series. J Palliat Med. Jul 2011;14(7):815–821; and Evangelista LS, Liao S, Motie M, De Michelis N, Lombardo D. On-going palliative care enhances perceived control and patient activation and reduces symptom distress in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a pilot study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. Apr 2014;13(2):116–123.

When & Where Should Team-Based Palliative Care Occur?

There is no clear consensus on the optimal timing and location of supportive care for patients with heart failure, except that early and iterative intervention is preferred. This stems from the concept that “difficult discussions now simplify difficult decisions later.”40 Nearly 20 years ago, the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) trial investigators identified substantial inadequacies in end-of-life care, but were unable to improve outcomes via a nurse-led, in-hospital, palliative care intervention.41 The authors suggested that repeated exposure throughout the disease span might be needed to affect positive change, in addition to a more developed healthcare infrastructure to support interventions. Indeed, subsequent literature solidified the importance of constantly readdressing goals and expectations for care with heart failure patients.42 The need for repetition stems from the unpredictable nature of heart failure progression,43 the ensuing difficulty with accurate risk assignation and prognosis,40 and the evolution of individual patient preferences over time.44 Ultimately, these difficulties might be attenuated by earlier integration of supportive care that fosters improved patients’ understanding and acceptance of their disease and mortality.45 Early and iterative supportive care integration might be more easily accomplished by a team of physicians, nurses, psychologists, and chaplains with skills different from but complementary to those of heart failure clinicians.

Early discussions regarding advance care decisions are preferable, primarily because they allow more time for coping and planning by patients and caregivers, alike.46,47 In a controlled trial of early outpatient palliative care for patients with various chronic diseases, 69% would have preferred the intervention regarding future plans to have occurred earlier.48 Provisional planning can help patients avoid struggling with unpredictable deteriorations in health status and mitigate the isolation and dependency that can accompany these declines, in part by identifying resources and support in advance.49 Early palliative heart failure interventions have been studied prospectively in outpatient9,15 and post-admission settings13,14,50 as well as among admitted patients undergoing their first heart transplant evaluation,16 with varying results (Table 1).

Unfortunately, late referrals to palliative care are common. One single-center retrospective chart review of 132 advanced heart failure patients receiving inpatient palliative care consults over 5 years reported an actual median time from consultation to death of only 21 days.45 Late hospice referrals were associated with worse family satisfaction with hospice, unmet needs, poor awareness about expectations for when death would occur, low confidence in being part of care, and perceived lack of care coordination.51

A number of locations for palliative heart failure interventions have been studied. Home-based palliative care was explored in multiple studies with mixed results regarding symptom burden, quality of life, healthcare utilization, and cost (Table 1), though rate of death at home was higher in each of these studies.8,10,12,17 This reflects the priorities of patients with end-stage heart failure, who prefer to be at home during the terminal stage of the disease, if possible.52 The challenges of community-based rural palliative care have been reviewed53 and tested in a feasibility pilot.11 When rural patients with heart failure face geographic barriers to access, the importance of a team leader or liaison, telephone communication support, and definitive, concrete, end-of-life plans are vital to success.53 Finally, although it seems intuitive that patients would prefer to face difficult decisions about their future in the outpatient setting, as opposed to during the stress of a hospitalization for acute decompensation, this concept has not been thoroughly explored.

One of the best models for an early, iterative, and efficacious supportive care intervention in patients with chronic disease was pioneered by medical ethicist Bernard (Bud) Hammes at Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin. His program, “Respecting Choices,” entails in-depth discussions about advance directives, facilitated by trained providers. Discussions are encouraged with all adults whenever they interact with healthcare professionals, whether inpatient or outpatient, primary care or specialty, physicians or other providers. Although the intervention only addresses one domain of supportive care, it has been associated with very high rates of advance directive completion, higher patient satisfaction and lower rates of healthcare utilization and costs in the last year of life.54,55

What Should Team-Based Heart Failure Palliative Care Include, and How Should Providers be Trained to Administer It?

A number of different supportive care stages have been put forth in expert reviews to delineate how the role of the multi-disciplinary palliative heart failure team changes with disease progression.22,23,56,57 From these and other studies, we have consolidated supportive care of the patient with heart failure into 6 domains and identified team members associated with service provision in each domain (Table 3). The expectation should be that different team members provide varying amounts of support at different times in the progression of disease, with the medical home (cardiology or primary care) and an appointed team liaison involved in coordination and continuity of care throughout.

Table 3.

Domains of supportive care and team members involved in early & late phases of heart failure progression

| DOMAINS | EARLY PHASE | LATE PHASE | TEAM MEMBERS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Well-being | Life-prolonging Heart Failure Therapies (Medications, Interventional Procedures) | Physician, Advanced Practice Provider (APP)*, Pharmacist | |

| Symptom Management (Pain, Dyspnea, Fatigue, Insomnia, Anorexia, Pruritus, Side Effects of Treatments/Interventions) | Physician, APP, Pain Specialist, Palliative Care Specialist (PCS), Pulmonologist, Respiratory Therapist, Pharmacist, Physical & Occupational Therapy (PT/OT) | ||

| Complementary & Alternative Medicine (as desired by the patient) | Acupuncturist, Clinical Art Therapist, Message Therapist, Yoga Instructor | ||

| Exercise/Weight Control/Nutrition | Rehabilitation/Strengthening | Physiatrist, PT/OT, Nutritionist | |

| Psychosocial Support | Quality of Life | ALL Team Members | |

| Community Resources (Insurance, Financial Aid, Support Groups) | Community Resources (Transportation, Home Care, Hospice) | Social Work, Case Management (SW/CM), Home Health, Support Group Facilitator, Hospice Team | |

| Spirituality | Chaplain | ||

| Depression, Anxiety | Physician, APP, Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Pharmacist, Chaplain, PCS, Support Group | ||

| Emotional Support, Coping | Loss of Control, Autonomy, Legacy Building | ||

| Communication | Appoint Team Liaison | Maintain Open, Trusting Relationship (“Meet patients where they are”) | Physician, APP, Caregiver, Team Liaison, PCS, Psychologist, Psychiatrist |

| Continuity of Care | |||

| Shared-decision Making, Assess Goals of Care | |||

| Disease Understanding | Prognostic Understanding (As patient wishes to know) | ||

| Addressing Fears & Concerns | |||

| Advance Care Planning | Legal (Advance directives—including living wills, appointment of alternate decision maker [health care power of attorney]) | Legal (Reassess Preferences and Goals of Care Frequently) | Physician, APP, SW/CM, PCS, Caregiver |

| Difficult Issues (Choosing a Place of Death; Avoiding Prolonged Suffering; Code status, Considering Hospice; De-escalation of Care; Preferences for Rehospitalization, Device Deactivation | Physician, APP, PCS, Caregiver, Hospice | ||

| Education | Self-management/Self-care (Adherence to Medication, Diet; Exercise) | Physician, APP, Pharmacist, Dietician, Physiatrist, PT/OT | |

| Understanding heart failure and the implications of the diagnosis | Understanding Unpredictable Course | Physician, APP | |

| Knowledge of Potentially Life-limiting Nature of Illness | |||

| Caregiver Focus | Preserve/Foster Relationships, Caregiver Agreement with/Acceptance of Patient Preferences | Caregiver | |

| Prevention of Caregiver Fatigue and Burnout | SW/CM, Support Group, Psychologist, Psychiatrist | ||

| Avoid Leaving Financial Burdens | Caregiver, SW/CM | ||

| Bereavement Support | Caregiver, Psychologist, Psychiatrist, SW/CM, Chaplain | ||

“Advanced Practice Provider” refers to nurse practitioners or physician assistants

Much work is needed to identify which supportive care interventions are most effective at different time points in heart failure progression. In one review, multidisciplinary interventions improved continuity of care, but there was little direct evidence supporting improved outcomes.58 For example, depression is common and associated with worse outcomes in advanced disease.59 However, anti-depressants had disappointing results when used in this setting.60 Therefore, depression in the setting of heart failure is likely to be most responsive to multi-modality interventions, including pharmacotherapy for cardiac dysfunction and other comorbidities, as well as exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy.61 Likewise, dyspnea is a common symptom that affects quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure. An often-quoted but small pilot study described improved shortness of breath in patients treated with opioids,62 while a number of studies have shown dyspnea improvement through exercise and respiratory muscle training.56 Even more promising is the Breathlessness Support Service, a UK-based intervention for patients with advanced diseases, including heart failure. In a randomized controlled trial, the intervention used behavioral therapy, fans/cooling techniques, and pulmonary therapists, in addition to common treatments, to improve outcomes.63

One of the challenges in provision of staged supportive care throughout the disease span is a lack of provider training to facilitate holistic care of the patient. In qualitative studies, providers avoided broaching palliative care issues with patients for a number of reasons, such as lack of time and resources, discomfort or self-perceived skill deficit in discussing sensitive issues, unpredictable disease course and uncertainty with timing of conversations, fear of negative effects on the patient, and perception of palliative care as synonymous with terminal care.64 However, patients mostly preferred hearing the truth, as long as they were asked permission to broach such topics, and such conversations did not take away their hope.40,65 Strong communication skills are of utmost importance in creating open, trusting patient-provider relationships, and palliative care communication training has been shown to be effective.66,67 A number of the heart failure-specific pilots and trials listed in Table 1 relied on at least some level of training for facilitators of palliative interventions.8,9,11,15 One pre/post-test design study even validated an interdisciplinary instructional seminar for non-physician heart failure providers on heart failure treatment guidelines and effective communication techniques.68 As with other skill sets, providers need to develop comfort with communication of difficult content. Given the shortage of palliative care providers in the US, structured educational interventions need to be tested to ensure that all team members are both able and willing to perform their duties, so that non-palliative care specialists can be empowered to excel in providing primary palliative care.34

Device-Related, Team-Based Palliative Care

Evaluation for potential long-term MCS represents a decision point at which a formal palliative care consultation should be considered, if circumstances allow. In fact, guidelines recommend palliative care consultation as part of a multidisciplinary approach5 to all patients being considered for MCS or cardiac transplantation at an experienced center.4 While MCS can offer extra years of life to a patient with terminal heart failure, it also creates new self-care69 and financial burdens,70 necessitates a strong infrastructure of provider and caregiver support, and imparts high risk for adverse events such as stroke, recurrent gastrointestinal bleed, chronic infection and pump failure, all of which can seriously affect quality of life.71 A number of reviews have helped to establish a consensus opinion regarding the importance of team-based care of the MCS patient before, during, and after device implantation.72,73

During the index admission for MCS, experts have advocated for a much more comprehensive advance care planning intervention. This has been referred to as “preparedness planning,” and takes into account multiple MCS-specific factors that are not addressed in traditional advanced directives (Table 4). Preparedness planning also requires open communication to establish realistic expectations and address difficult topics such as triggers for device withdrawal.75 In one single-center study, using a multidisciplinary approach, length of stay was decreased, and costs and 30-day readmissions were reduced,76 but larger controlled trials are needed to establish efficacy and patient satisfaction.

Table 4.

Common differences between traditional advance directives and preparedness plans in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy

| Measure to be considered | Advance Directive | Preparedness Plan |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics. long term role | + | ++ |

| Artificial nutrition | + | ++ |

| Blood transfusions | + | ++ |

| Goals and expectations | − | ++ |

| Hemodialysis | + | ++ |

| Hydration | + | ++ |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | − | ++ |

| LVAD failure | − | ++ |

| LVAD infection | − | ++ |

| Organ donation | ++ | ++ |

| Mechanical ventilation | ++ | ++ |

| Post-operative plans for rehabilitation | − | ++ |

| Power of Attorney appointed | ++ | ++ |

| Psychosocial assessment | − | ++ |

| Review of perioperative morbidity and mortality | − | ++ |

| Social dynamics reviewed | − | ++ |

| Spiritual and/or religious preferences | ++ | ++ |

| Stroke | − | ++ |

Notation: “−” not generally found in document; “+” may be found in document, “++” often found in document.

Data from Swetz KM, Freeman MR, AbouEzzeddine OF, et al. Palliative medicine consultation for preparedness planning in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. Jun 2011;86(6):493–500.

The complexities of living with MCS necessitate continued team-based care after discharge. Adjusting to new limitations, fear of device malfunction, and conflicting feelings of hope and uncertainty for the future all created great psychosocial stress for patients,77 and were associated with post-traumatic stress disorder in caregivers.78 Successful models of outpatient, community-based care of MCS patients rely on significant contributions from multiple team members, as well as dedication to adherence from patients and caregivers.79 Finally, device deactivation at end-of-life for patients with MCS is often necessary to allow death. Navigating this ethically complex and challenging issue with patients calls for assistance and support from palliative care specialists.80

GAPS IN KNOWLEDGE; FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although a fair amount of expert opinion and consensus has been published regarding the importance of a team-based approach to palliative care in heart failure, prospective studies are lacking. Important gaps include the feasibility and effectiveness of utilizing non-palliative care specialists as purveyors of primary palliative care, optimal components of comprehensive palliative interventions, and long-term outcomes associated with early and iterative advance care planning. The greatest challenge is less tangible: we must change the culture such that all providers of healthcare services embrace palliative care, not as terminal or comfort care of the dying patient, but as supportive, holistic care of all patients. Those who treat patients with heart failure must take up the cause of treating not just the disease, but the person with the disease.

To that end, the same team-based approach that we believe can optimize outcomes for patients with heart failure should be applied to optimizing delivery of palliative heart failure care. In line with the concept of a medical home that provides and coordinates continuous care throughout the disease span for patients with heart failure, many successful trials, pilots, and single-center programs used inter-disciplinary conferences that met regularly to discuss their patient cohort.8–10,81 This team-based conference model allows for: 1) a healthy exchange of ideas and reciprocal learning among professionals, 2) prioritization of competing treatment preferences based on that which most benefits patients, 3) coordination of services to minimize redundancy, 4) mutability of individualized treatment plans as the disease progresses, and 5) streamlined communication between patients and the team to maximize understanding and trust.

Continuity of care in a heart failure medical home would not just be a temporal concept across the patient’s lifespan, but also an interdisciplinary one across various specialty providers of holistic healthcare. The hierarchy of the heart failure medical home would have both stability, in that appointed team liaisons would consistently provide a reliable interface between team and patient, and fluidity, in that central/primary and peripheral/consultative patient care roles might vary by individual patient and change over time. We would contend that the concept of an annual heart failure review, put forth previously in a statement from the AHA on decision-making in heart failure,40 might offer the ideal setting for periodic re-assessment of patients’ goals, values and preferences as they change, whether it occurs in the office of a primary care doctor, heart failure cardiologist, or palliative care specialist.

SUMMARY

Palliative care in heart failure should no longer be thought of as comfort administered to dying patients; it should instead refer to team-based, holistic, supportive care of patients across the span of heart failure progression, beginning early in the disease process, intensifying at patients’ end-of-life, and extending into the bereavement phase for their caregivers. It must iteratively address patients’ values, goals, and preferences regarding treatment, quality of life, and survival. As such, the team will change and grow in a manner reflective of changes and growth in patients during the span of the disease. A broad range of providers must be trained in communication techniques and intra-disciplinary collaboration skills to ensure their confidence and ability in approaching the whole patient. How best to deliver such care will require further research to establish cost-effective, feasible, and sustainable models of multi-disciplinary heart failure care.

KEY POINTS.

Palliative care is one component of holistic, supportive care of the patient throughout the course of disease, intensified at end-of-life and extending into the bereavement phase for their caregivers.

Team-based palliative care for heart failure implies a multidisciplinary approach, including primary care, cardiology, and palliative care, each represented by various providers (e.g. physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, case managers, and pharmacists).

Patients require a “heart failure medical home”, where various specialties may take a more central role in coordination of patient care at different times in the disease span, sometimes with consultation by palliative care and sometimes transitioning focus to palliative care at the end of life.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no relevant disclosures.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Fendler is supported by a T32 grant from the NHLBI (T32HL110837).

Otherwise, all other coauthors have no relevant disclosures or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Timothy J. Fendler, Email: swetz.keith@mayo.edu.

Larry A. Allen, Email: larry.allen@ucdenver.edu.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013 Jan 1;127(1):e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America IoM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, Wagner EH. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004 Aug;13(4):299–305. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Oct 15;128(16):e240–327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013 Feb;32(2):157–187. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gohler A, Januzzi JL, Worrell SS, et al. A systematic meta-analysis of the efficacy and heterogeneity of disease management programs in congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006 Sep;12(7):554–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grady KL, Dracup K, Kennedy G, et al. Team management of patients with heart failure: A statement for healthcare professionals from The Cardiovascular Nursing Council of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000 Nov 7;102(19):2443–2456. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med. 2006 Feb;9(1):111–126. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekelman DB, Hooker S, Nowels CT, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a collaborative care intervention to improve symptoms and quality of life in chronic heart failure: mixed methods pilot trial. J Palliat Med. 2014 Feb;17(2):145–151. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brannstrom M, Boman K. Effects of person-centred and integrated chronic heart failure and palliative home care. PREFER: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014 Oct;16(10):1142–1151. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dionne-Odom JN, Kono A, Frost J, et al. Translating and testing the ENABLE: CHF-PC concurrent palliative care model for older adults with heart failure and their family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2014 Sep;17(9):995–1004. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enguidanos SM, Cherin D, Brumley R. Home-based palliative care study: site of death, and costs of medical care for patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005;1(3):37–56. doi: 10.1300/J457v01n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evangelista LS, Motie M, Lombardo D, Ballard-Hernandez J, Malik S, Liao S. Does preparedness planning improve attitudes and completion of advance directives in patients with symptomatic heart failure? J Palliat Med. 2012 Dec;15(12):1316–1320. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evangelista LS, Liao S, Motie M, De Michelis N, Lombardo D. On-going palliative care enhances perceived control and patient activation and reduces symptom distress in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a pilot study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014 Apr;13(2):116–123. doi: 10.1177/1474515114520766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schellinger S, Sidebottom A, Briggs L. Disease specific advance care planning for heart failure patients: implementation in a large health system. J Palliat Med. 2011 Nov;14(11):1224–1230. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarz ER, Baraghoush A, Morrissey RP, et al. Pilot study of palliative care consultation in patients with advanced heart failure referred for cardiac transplantation. J Palliat Med. 2012 Jan;15(1):12–15. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong RC, Tan PT, Seow YH, et al. Home-based advance care programme is effective in reducing hospitalisations of advanced heart failure patients: a clinical and healthcare cost study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013 Sep;42(9):466–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lankan PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Apr 15;177(8):912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1990;804:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler ED, Goldfinger JZ, Kalman J, Park ME, Meier DE. Palliative care in the treatment of advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2009 Dec 22;120(25):2597–2606. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.869123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, et al. Consensus statement: Palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004 Jun;10(3):200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauptman PJ, Havranek EP. Integrating palliative care into heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Feb 28;165(4):374–378. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009 May;11(5):433–443. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rangachari D, Smith TJ. Integrating palliative care in oncology: the oncologist as a primary palliative care provider. Cancer J. 2013 Sep-Oct;19(5):373–378. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3182a76b9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Mar 10;30(8):880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, et al. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: a comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 May;24(5):592–598. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0931-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Stedman M, Flavell CM, Levin R, Stevenson LW. Hospice, opiates, and acute care service use among the elderly before death from heart failure or cancer. Am Heart J. 2010 Jul;160(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanvetyanon T, Leighton JC. Life-sustaining treatments in patients who died of chronic congestive heart failure compared with metastatic cancer. Crit Care Med. 2003 Jan;31(1):60–64. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaarsma T, Brons M, Kraai I, Luttik ML, Stromberg A. Components of heart failure management in home care; a literature review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013 Jun;12(3):230–241. doi: 10.1177/1474515112449539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunlay SM, Foxen JL, Cole T, et al. A survey of clinician attitudes and self-reported practices regarding end-of-life care in heart failure. Palliat Med. 2014 Dec 8; doi: 10.1177/0269216314556565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, et al. “Not the ‘grim reaper service’”: an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Amer Heart Assoc. 2014;3(1):e000544. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swetz KM, Kamal AH. In the clinic. Palliative care. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Feb 7;156(3):ITC2-2–ITC2-16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-01002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lupu D. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010 Dec;40(6):899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013 Mar 28;368(13):1173–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daley A, Matthews C, Williams A. Heart failure and palliative care services working in partnership: report of a new model of care. Palliat Med. 2006 Sep;20(6):593–601. doi: 10.1177/0269216306071060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, De Geest S, et al. Heart failure management programmes in Europe. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006 Sep;5(3):197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segal DI, O’Hanlon D, Rahman N, McCarthy DJ, Gibbs JS. Incorporating palliative care into heart failure management: a new model of care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005 Mar;11(3):135–136. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.3.18033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyd KJ, Worth A, Kendall M, et al. Making sure services deliver for people with advanced heart failure: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients, family carers, and health professionals. Palliat Med. 2009 Dec;23(8):767–776. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Allen LA, Shakar S, Kutner JS, Matlock DD. Outpatient palliative care for chronic heart failure: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2011 Jul;14(7):815–821. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012 Apr 17;125(15):1928–1952. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. J Am Med Assoc. 1995 Nov 22–29;274(20):1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins LG, Parks SM, Winter L. The state of advance care planning: one decade after SUPPORT. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006 Oct-Nov;23(5):378–384. doi: 10.1177/1049909106292171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 1;362(13):1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevenson LW, Hellkamp AS, Leier CV, et al. Changing preferences for survival after hospitalization with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Nov 18;52(21):1702–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakitas M, Macmartin M, Trzepkowski K, et al. Palliative care consultations for heart failure patients: how many, when, and why? J Card Fail. 2013 Mar;19(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barclay S, Momen N, Case-Upton S, Kuhn I, Smith E. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 Jan;61(582):e49–62. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X549018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Retrum JH, et al. Giving voice to patients’ and family caregivers’ needs in chronic heart failure: implications for palliative care programs. J Palliat Med. 2011 Dec;14(12):1317–1324. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rabow MW, Petersen J, Schanche K, Dibble SL, McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: a description of a controlled trial of care at the beginning of the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2003 Jun;6(3):489–499. doi: 10.1089/109662103322144862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson JS, et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med. 2007 Jun;21(4):313–322. doi: 10.1177/0269216307077711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evangelista LS, Lombardo D, Malik S, Ballard-Hernandez J, Motie M, Liao S. Examining the effects of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012 Dec;18(12):894–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teno JM, Shu JE, Casarett D, Spence C, Rhodes R, Connor S. Timing of referral to hospice and quality of care: length of stay and bereaved family members’ perceptions of the timing of hospice referral. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007 Aug;34(2):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Formiga F, Chivite D, Ortega C, Casas S, Ramon JM, Pujol R. End-of-life preferences in elderly patients admitted for heart failure. QJM. 2004 Dec;97(12):803–808. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernando J, Percy J, Davidson L, Allan S. The challenge of providing palliative care to a rural population with cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2014 Mar;8(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Dartmouth Atlas Working Group. [Accessed December, 2014];The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. http://wwwdartmouthatlas.org/

- 55.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL. Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012 May;60(5):946–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodlin SJ. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Jul 28;54(5):386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morrison RS, Meier DE. Clinical practice. Palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jun 17;350(25):2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp035232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):147–159. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Oct 17;48(8):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glassman AH, O’Connor CM, Califf RM, et al. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. J Am Med Assoc. 2002 Aug 14;288(6):701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rustad JK, Stern TA, Hebert KA, Musselman DL. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in patients with congestive heart failure: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4) doi: 10.4088/PCC.13r01511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson MJ, McDonagh TA, Harkness A, McKay SE, Dargie HJ. Morphine for the relief of breathlessness in patients with chronic heart failure--a pilot study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002 Dec;4(6):753–756. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Higginson IJ, Bausewein C, Reilly CC, et al. An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2600(14):70226–70227. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, Gordon HS. “There’s no cure for this condition”: how physicians discuss advance care planning in heart failure. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 May;91(2):200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007 Sep;21(6):507–517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gelfman LP, Lindenberger E, Fernandez H, et al. The effectiveness of the Geritalk communication skills course: a real-time assessment of skill acquisition and deliberate practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014 Oct;48(4):738–744. e731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schell JO, Green JA, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. Communication skills training for dialysis decision-making and end-of-life care in nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 Apr;8(4):675–680. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05220512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zapka JG, Hennessy W, Lin Y, Johnson L, Kennedy D, Goodlin SJ. An interdisciplinary workshop to improve palliative care: advanced heart failure--clinical guidelines and healing words. Palliat Support Care. 2006 Mar;4(1):37–46. doi: 10.1017/s1478951506060056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Casida J, Peters R, Magnan M. Self-care demands of persons living with an implantable left-ventricular assist device. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2009;23(4):279–293. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.23.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bieniarz MC, Delgado R. The financial burden of destination left ventricular assist device therapy: who and when? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2007 May;9(3):194–199. doi: 10.1007/BF02938350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: a 10,000-patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014 Jun;33(6):555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goldstein NE, May CW, Meier DE. Comprehensive care for mechanical circulatory support: a new frontier for synergy with palliative care. Circ Heart Fail. 2011 Jul;4(4):519–527. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.957241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Swetz KM, Ottenberg AL, Freeman MR, Mueller PS. Palliative care and end-of-life issues in patients treated with left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2011 Sep;8(3):212–218. doi: 10.1007/s11897-011-0060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swetz KM, Freeman MR, AbouEzzeddine OF, et al. Palliative medicine consultation for preparedness planning in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Jun;86(6):493–500. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mueller PS, Swetz KM, Freeman MR, et al. Ethical analysis of withdrawing ventricular assist device support. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Sep;85(9):791–797. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murray MA, Osaki S, Edwards NM, et al. Multidisciplinary approach decreases length of stay and reduces cost for ventricular assist device therapy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009 Jan;8(1):84–88. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.187377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.MacIver J, Ross HJ. Withdrawal of ventricular assist device support. J Palliat Care. 2005 Autumn;21(3):151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heilmann C, Kuijpers N, Beyersdorf F, et al. Supportive psychotherapy for patients with heart transplantation or ventricular assist devices. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011 Apr;39(4):e44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilson SR, Givertz MM, Stewart GC, Mudge GH., Jr Ventricular assist devices the challenges of outpatient management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Oct 27;54(18):1647–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brush S, Budge D, Alharethi R, et al. End-of-life decision making and implementation in recipients of a destination left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010 Dec;29(12):1337–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mitchell G, Zhang J, Burridge L, et al. Case conferences between general practitioners and specialist teams to plan end of life care of people with end stage heart failure and lung disease: an exploratory pilot study. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]