Abstract

Background:

In Ayurveda, Vrana (wound) has stated as tissue destruction and discoloration of viable tissue due to various etiology. In Sushruta Samhita, Sushruta described Vrana as a main subject. Most commonly Vrana can be classified into Shuddha and Dushta Vrana (chronic wound/nonhealing ulcers). Among the various drugs mentioned for Dushta Vrana, two of them, Neem (Azadirechta indica A. Juss) oil and Haridra (Curcuma longa Linn.) powder are selected for their wide spectrum action on wound.

Aim:

To compare the effect of Neem oil and Haridra in the treatment of chronic non-healing wounds.

Materials and Methods:

Total 60 patients of wounds with more than 6 weeks duration were enrolled and alternatively allocated to Group I (topical application of Neem oil), Group II (Haridra powder capsules, 1 g 3 times orally) and Group III (both drugs). Duration of treatment was considered until complete healing of the wound, whereas 4th and 8th week were considered for assessment of 50% healing. Wound size was measured and recorded at weekly intervals. Wound biopsy was repeated after 4 weeks for assessment of angiogenesis and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis.

Results:

After 8 weeks of treatment, 50% wound healing was observed in 43.80% patients of Group I, 18.20% patients of Group II, and 70.00% patients of Group III. Microscopic angiogenesis grading system scores and DNA concentration showed highly significant effect of combined use of both drugs when compared before and after results of treatment (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Topical use of Neem oil and oral use of Haridra powder capsule used in combination were found effective for chronic non-healing wounds.

Keywords: Chronic wound, Haridra, microscopic angiogenesis grading system score, Neem oil, wound healing

Introduction

Vrana (wound) and its management has been dealt since the period of the Veda to current era.[1] It has been a major problem since the early stage of medical science. Chronic nonhealing wounds present serious problems for patients, family, and clinicians. Most are associated with a small number of underlying disorders such as diabetes, leprosy, and peripheral vascular diseases.[2] The development of pharmacological agents (antibiotics, vasodilators, antioxidant, and Vitamins) has enhanced the healing of acute as well as chronic wounds. In spite of all these recent advances lacunae still persists. Wound infection has been one of the major impediments in the process of wound healing and after invention of antibiotics; it was thought that this problem would be conquered. Since then, several antibiotics in the form of systemic and local use have been tried, but problems of chronic wound healing remain as such. Research on wound healing drugs is a potential area in biomedical sciences. Ayurveda, the Indian traditional system of medicine, mentions the values of many medicinal plants for wound healing. Scientists who are trying to explore newer drugs from natural resources are looking towards Ayurveda because phyto-medicines are not only affordable, but are comparatively safe also. Several drugs from plant, mineral, and animal origin are described in Ayurveda for their wound healing properties under the term Vranaropaka (wound healing agent). Wound healing activities of some plants have been screened scientifically in different pharmacological models and patients, but the potential of most of them still remains unexplored. Some Ayurvedic plants, namely Vata (Ficus bengalensis Linn.), Durva (Cynodon dactylon Pers.), Lodhra (Symplocos racemosa Roxb.), Manjishtha (Rubia cordifolia Linn.), Chandan (Pterocarpus santalinus Linn. f.), Gular (Ficus racemosa Roxb.), Yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza glabra Linn.), Daruharidra (Berberis aristata DC.), Haridra (Curcuma longa Linn.), Mandukaparni (Centella asiatica (Linn.) Urban), Snuhi (Euphorbia nerifolia Linn.), and Ghrita Kumarai (Aloe vera Tourn. ex Linn.) were found to be effective in experimental models.[3] Among them two drugs Azadirechta indica A. Juss and C. longa were selected here for clinical assessment in chronic non-healing wounds. Most of the chronic non-healing wounds are associated with co-morbid conditions such as diabetes, leprosy and peripheral vascular disease.[2] Various topical agents such as growth factors and angiogenic factors are gaining importance in wound care[4,5] and are used for the treatment of underlying co-morbidities.

Materials and Methods

Sixty patients attending the Wound Clinic at University Hospital, Varanasi were enrolled for this study. This study was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee (Letter No. Dean/2006–07/881, Dated: December 12, 2006).

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged between 19 and 78 years of either sex

Patients with non-healing chronic wounds of more than 6 weeks duration were included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients having malignant wounds, osteomyelitis, and unwillingness to attend the clinic regularly for treatment and assessment were excluded.

Laboratory investigations

Blood investigations were done for hemoglobin%, total leukocyte count differential leukocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, total serum protein, serum albumin, blood sugar, and blood urea.

Grouping and treatment protocols

Among 60 patients only 47 patients were completed the treatment and they were alternately allocated into three groups:

Group I: Wounds were treated with topical use Neem oil only (n = 16)

Group II: Haridra capsule 1 g 3 times a day orally (n = 11)

Group III: Both the drugs were administered, that is, Neem oil for topical application and Haridra capsule 1 g 3 times a day orally (n = 20).

For the present work, the oil is prepared by pressing (cold pressed method) of Neem seed kernel.

Dressings were changed daily in patients of all three groups. Duration of treatment considered till complete healing of wound and 4th and 8th week is only for assessment of 50% healing because study sample was small.

Assessment criteria

Wound area

Size of the wound was recorded by tracing the perimeter of the wound on transparent plastic sheets at every 2 weeks. Wound size (percentage area of wound healed/total area of wound × 100) was assessed.

Microscopic angiogenesis grading system score

Biopsies were performed before initiating the treatment and after 4 weeks of treatment to assess angiogenesis. These were analyzed using the microscopic angiogenesis parameters of endothelial cell regeneration: Vasoproliferation, endothelial cell hyperplasia and endothelial cytology. A numerical grade was given to each variable and a simple equation was used to calculate the overall index of endothelial regeneration – the microscopic angiogenesis grading system (MAGS) score.[6,7]

Formula used to calculate the MAGS score:

MAGS = KaN + KbE + KcX

(N = Number of capillaries per high power field, Ka = 1, E = Number of endothelial cells lining the cross-section of a capillary, Kb = 3, X = Endothelial cell cytology on a scale of 0–5, Kc = 6, Ka, Kb, and Kc are constants with fixed values of 1, 3, and 6, respectively).

Endothelial cell cytology scale:

0 = Normal cell: Thin, flat, well-differentiated nucleus;

1 = Plump, clear nucleus;

2 = Plump, clear nucleus plus prominent nucleolus;

3 = Large hyperchromatic nucleus;

4 = Irregular endothelial cell that cannot be classified as containing mitotic or hyperchromatic nuclei;

5 = Mitotic figure.

Deoxyribonucleic acid analysis

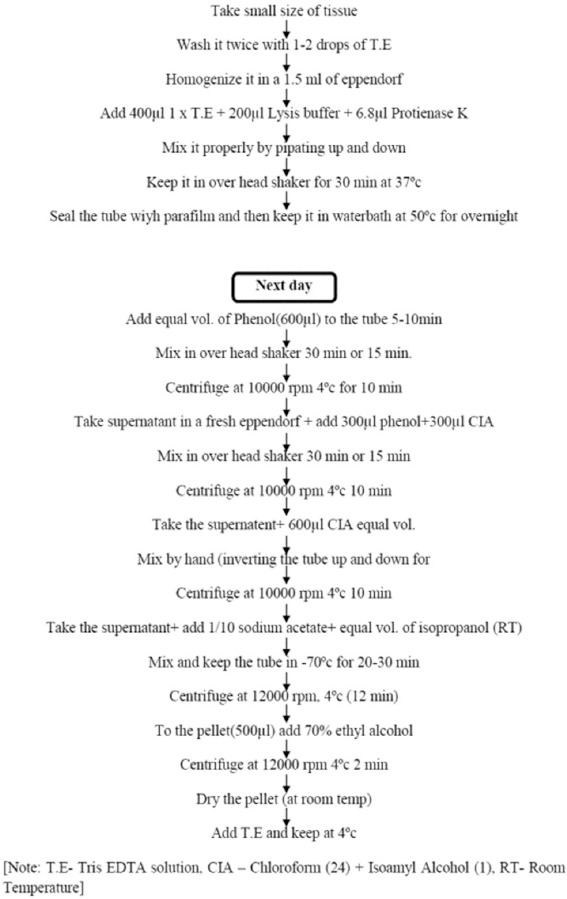

DNA content estimation was done in the sample of wound tissue by phenol-chloroform method [Chart 1]. Tissue was kept in ribonucleic acid later solution at −70°C temperature for DNA assessment.[8] DNA assessment was done twice that is before treatment and after 4 weeks of scheduled treatment.

Chart 1.

Phenol chloroform method for deoxyribonucleic acid estimation in tissue

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using the ANOVA test to compare MAGS score in all groups. The distribution of DNA variable did not follow the normal distribution; therefore, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to find out the significant difference at mean level in various study groups.

Observations

All three groups were considered in terms of patients characteristics (means characters related to wound like site of the wound, type of wound, duration of wound, etc.). Wound duration ranged from 1.5 to 3 months in 12 patients, 3 to 6 months in 9 patients, 6 to 12 months in 10 patients, 12 to 36 months in 10 patients, 36 months and above in 6 patients. Mean duration in Group I was 61.56 ± 189.05 (range 6–77) weeks, 14.82 ± 19.18 (range 6–72) weeks Group II, 29.85 ± 79.32 (range 6–36) weeks in Group III.

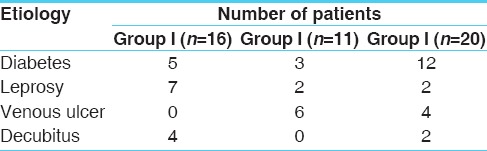

The ulcer was on lower limb in 93.61% of patients. When the data for the lower limb was analyzed for the exact location of the wound, it was found that the plantar aspects of feet were the most common sites. The plantar aspect of the foot accounted for 29.9% of ulcers among 47 cases. Diabetes (42.55%) was the most common underlying cause of the nonhealing ulcers, followed by leprotic (24.4%), venous ulcer (21.28%), and pressure ulcer (12.77%) [Table 1]. The patients had previously used other topical preparations, including antibiotic ointments and antiseptic creams for varying lengths of time. Those with leprosy had received antileprotic treatment, which resulted in minimal improvement in healing.

Table 1.

Etiology of non-healing wounds

Results

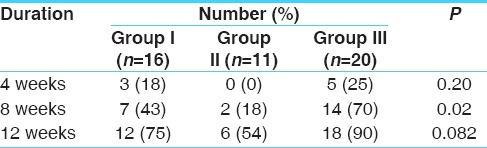

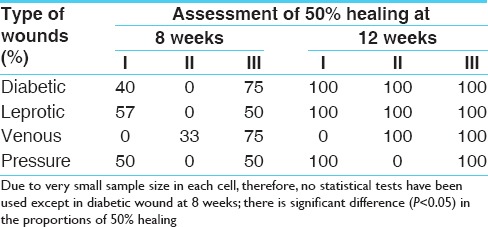

More than 50% healing at 12 weeks was observed in 75% of cases in Group I, 54% in Group II and 90% in Group III with P = 0.082, which shows statistical insignificance of healing in Group III. Beneficial effects of therapy were obvious from 4th week onwards. Among these patients pus and discharge decreased and granulation tissue began to appear by 2nd week, only one patient of Group III showed hypergranulation tissue formation [Table 2].

Table 2.

Evidence of >50% wound healing during treatment in three groups

Those wounds that achieved 50% healing at the end of 8 weeks were, 43% in Group I, 18% in Group II, and 70% in Group III.

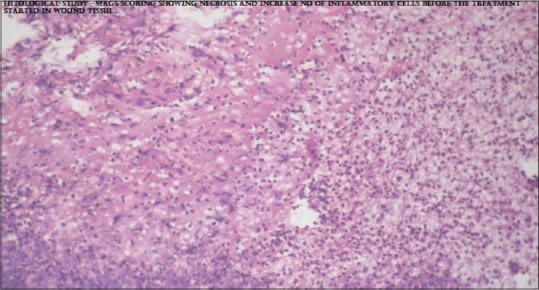

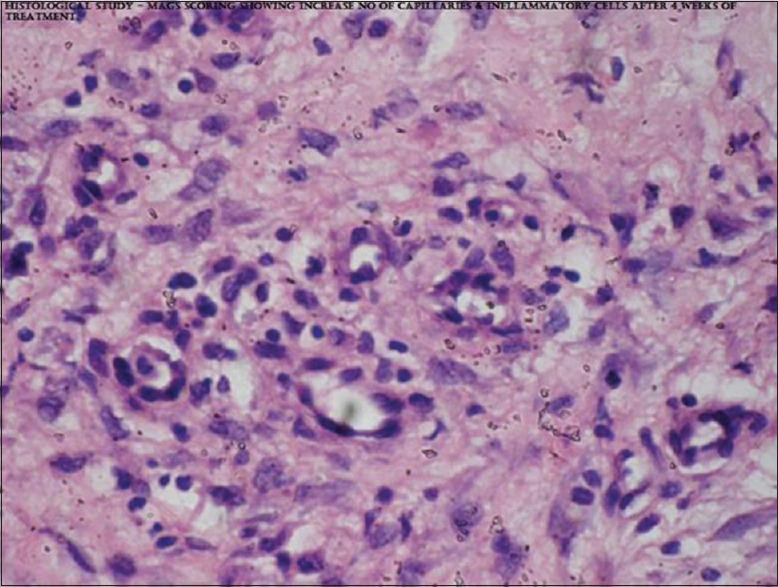

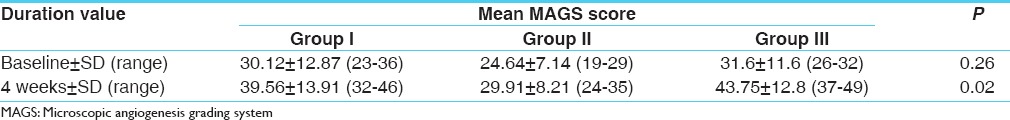

Increased angiogenesis was evident after four weeks in all groups when histopathological assessment was undertaken to identify MAGS scores [Figures 1 and 2]. Statistically significant difference was observed in MAGS scores among all groups and P = 0.02 after treatment [Table 3].

Figure 1.

Microscopic angiogenesis grading system score in wound tissue before treatment

Figure 2.

Microscopic angiogenesis grading system score in wound tissue after 4 week of treatment

Table 3.

Mean MAGS scores achieved following treatment within three groups

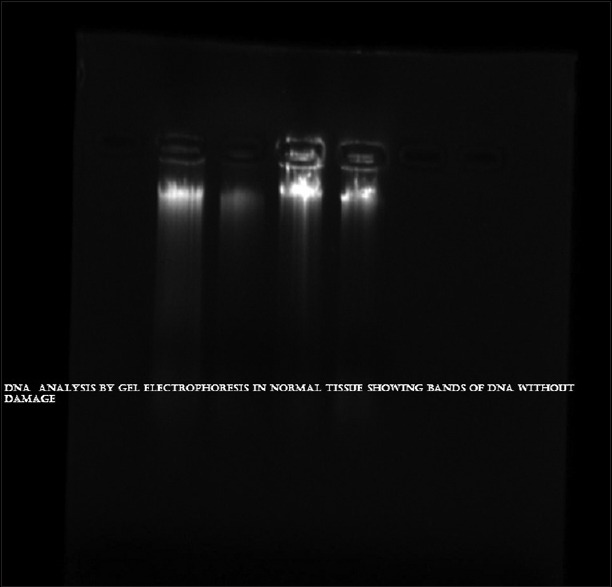

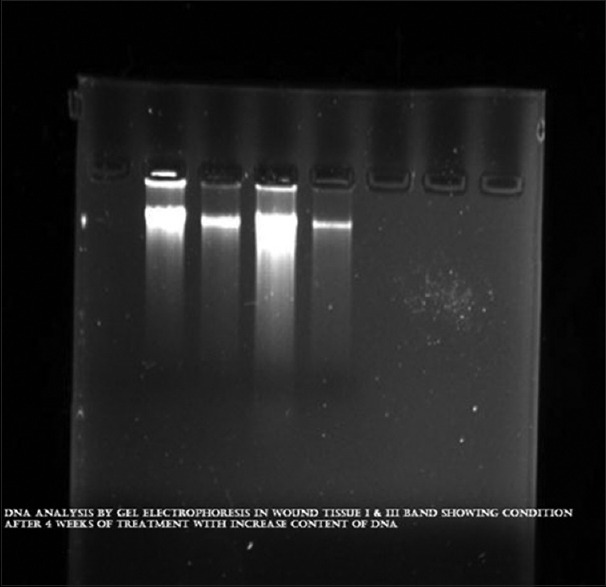

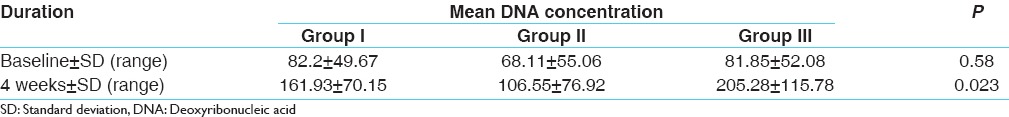

Deoxyribonucleic acid concentration (ng/μl) in wound tissue at the interval of four weeks showed statistically significant difference in all three groups [Figures 3 and 4]. The significant difference among the mean DNA was observed after treatment (P = 0.023). Thereafter, Mann–Whitney U-test was used to find the pair wise difference in mean [Table 4]. Figure 5 shows effect of therapy before and after treatment in some of the patients.

Figure 3.

Deoxyribonucleic acid concentration in wound tissue before treatment

Figure 4.

Deoxyribonucleic acid concentration in wound tissue after 4 week of treatment

Table 4.

DNA concentration achieved within three groups

Figure 5.

Wound healing at different stages

Results of ≥50% healing among different types of wounds

There is very small number of patients in each cell; therefore, no statistical tests have been used except in diabetic wound at eight weeks. There is a significant difference (P < 0.05) in the proportions of more than 50% healing. In diabetic wound up to eight weeks 40% healing seen in Group I, 0% in Group II and 75% in Group III, in leprotic wound up to eight weeks percentage healing was 57%, 0% and 50% in Group I, II, and III, respectively. In Venous ulcer 50% healing at eight week shows 0%, 33% and 75% in Group I, II, and III [Table 5].

Table 5.

Results of more than 50% healing in wounds among different types of wounds in the study

Histopathological examination and DNA assessment of 47 cases showed that combined use of both drugs showed a significant effect in Group III.

Discussion

In spite of brilliant progress in surgery, wound management still remains a subject of speculation and the early manifestation of unsatisfactory healing pose serious complication leading to prolonged healing and even death in surgical practice.[9]

It was already said that non-healing and chronic wounds are mostly concerned with a diabetic condition.[10] In the case of diabetic ulcer the effect of Neem oil (A. indica) and Haridra (C. longa), there is a synergetic effect of both drugs, while when they are used alone is not very significant. However, it is observed that use of Neem oil alone is comparatively better than the single use of Haridra capsule.

This study showed that combined use of Neem oil and Haridra can be a better option for chronic non healing wounds. MAGS scores revealed that it promoted vascular proliferation and DNA concentration in the regenerated tissues. Nimbidin, the principal component of Neem oil, is highly bitter and contains sulfur[11] and sulfur has antifungal, antibacterial and keratolytic properties.[12]

Rhizome of Haridra is brownish, yellow in color and powder of Haridra is used systemically for wound healing. It possess antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory activities.[13] It is useful in inflammations, ulcers, wounds, leprosy, skin diseases and allergic conditions.[14] Rhizomes of it contain curumin (diferuloylmethane), turmeric oil or turmerol and 1,7-bis, 6-hepta-diene-3, 5-dione, proteins, fat, Vitamin A, B, and C. Curcumin has potent anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities.[15] The anti-inflammatory property and the presence of Vitamin A and proteins in turmeric result in the early synthesis of collagen fibers by mimicking fibroblastic activity.[16]

Antimicrobial effects of Neem extract have been demonstrated against Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus faecalis.[17] Similarly, curcumin is an important constituent of turmeric powder, has shown faster wound closure of punch wounds by re-epithelialization of the epidermis and increased migration of various cells including myofibroblasts, fibroblasts, and macrophages in the wound bed. Multiple areas within the dermis showed extensive neo-vascularization as well.[18]

Conclusion

In this study, the topical use of Neem (A. indica) oil and systemic use of Haridra (C. longa) in both groups were found effective in healing the chronic wound. Both drugs have proven value in the management of non-healing wounds. They have also angiogenic property and potency to increase DNA content as well. The combination of Neem and Haridra is best to treat diabetic chronic wounds in a better way, both drugs showed a remarkable effect in leprotic, venous, and decubitus ulcer as well. In view of no any adverse effects and affordable economically by all, it can be recommend in combination for the treatment of chronic non healing wound.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Global Lower Extremity Amputation Study Group. Epidemiology of lower extremity amputation in centres in Europe, North America and East Asia. The Global Lower Extremity Amputation Study Group. Br J Surg. 2000;87:328–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shukla VK, Rasheed MA, Kumar M, Gupta SK, Pandey SS. A trial to determine the role of placental extract in the treatment of chronic non-healing wounds. J Wound Care. 2004;13:177–9. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2004.13.5.26668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas TK, Mukherjee B. Plant medicines of Indian origin for wound healing activity: A review. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2003;2:25–39. doi: 10.1177/1534734603002001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shun A, Ramsey-Stewart G. Human amnion in the treatment of chronic ulceration of the legs. Med J Aust. 1983;2:279–83. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1983.tb122464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheon SS, Nadesan P, Poon R, Alman BA. Growth factors regulate beta-catenin-mediated TCF-dependent transcriptional activation in fibroblasts during the proliferative phase of wound healing. Exp Cell Res. 2004;15(293):267–74. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar M, Tandon V, Singh PB, Mitra S, Vyas N. Angiogenesis and histologic scoring in prostatic carcinoma: A valuable cost effective prognostic indicator. Uro Oncol. 2004;4:139. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brem S, Cotran R, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: A quantitative method for histologic grading. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972;48:347–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; pp. 604–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boateng JS, Matthews KH, Stevens HN, Eccleston GM. Wound healing dressings and drug delivery systems: A review. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:2892–923. doi: 10.1002/jps.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chronic wound. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. [Last modified on 2014 May 02; Last accessed on 2014 Jun 17]. Available from: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chronic_wound .

- 11.Sharma PC, Yelne MB, Dennis TJ. I. New Delhi: CCRAS (Dept of AYUSH, Min. of Health and F. W., Govt of India); 2007. Database on Medicinal Plants Used in Ayurveda and Siddha; p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauder DN, Miller R, Gratton D, Danby W, Griffiths C, Phillips SB. The treatment of rosacea: The safety and efficacy of sodium sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% lotion (Novacet) is demonstrated in a double-blind study. Dermatolog Treat. 1997;8:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chopra RN, Chopra IC, Nayar SL. New Delhi: Publications and Information Directorate, CSIR; 1956. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma PC, Yelne MB, Dennis TJ. I. New Delhi: CCRAS (Dept. of Ayush, Min. of Health and F. W., Govt of India); 2007. Database on Medicinal Plants Used in Ayurveda and Siddha; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohli KR, Ali J, Ansari MJ, Raheman Z. Curcumin: A natural anti-inflammatory agent. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005;37:141. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Sharma VK, Singh HP, Prakash P, Singh SP. Efficacy of some indigenous drugs in tissue repair in buffaloes. Indian Vet J. 1993;70:42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nayaka A, Nayak RN, Saumya BG, Bhat K, Kudalkar M. Evaluation of antibacterial and anticandidial efficacy of aqueous and alcoholic extract of Neem an in-vitro study. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2011;2:230. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sidhu GS, Singh AK, Thaloor D, Banaudha KK, Patnaik GK, Srimal RC, et al. Enhancement of wound healing by curcumin in animals. Wound Repair Regen. 1998;6:167–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1998.60211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]