Abstract

Background

Obesity is a major health problem that disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic adults. This paper presents the rationale and innovative design of a small change eating and physical activity intervention (SC) combined with a positive affect and self-affirmation (PA/SA) intervention versus the SC intervention alone for weight loss.

Methods

Using a mixed methods translational model (EVOLVE), we designed and tested a SC approach intervention in overweight and/ or obese African American and Hispanic adults. In Phase I, we explored participant’s values and beliefs about the small change approach. In Phase II, we tested and refined the intervention and then, in Phase III we conducted a RCT. Participants were randomized to the SC approach with PA/SA intervention vs. a SC approach alone for 12 months. The primary outcome was clinically significant weight loss at 12 months.

Results

Over 4.5 years a total of 574 participants (67 in Phase I, 102 in Phase II and 405 in Phase III) were enrolled. Phase I findings were used to create a workbook based on real life experiences about weight loss and to refine the small change eating strategies. Phase II results shaped the recruitment and retention strategy for the RCT, as well as the final intervention. The RCT results are currently under analysis.

Conclusion

The present study seeks to determine if a SC approach combined with a PA/SA intervention will result in greater weight loss at 12 months in Black and Hispanic adults compared to a SC approach alone.

Keywords: weight loss, eating behaviors, small changes, physical activity, mixed methods, randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

Among Black and Latino adults, obesity is an epidemic.[1] In New York City, 70% of Blacks and 66% of Latinos are overweight or obese. [2] Obesity undoubtedly contributes to the excess burden of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in minority populations.[3] In spite of this disparity there are still relatively few randomized controlled trials focused solely on achieving weight loss in this high risk group. [4–6] Thus, developing behavioral interventions that target obesity-related behaviors in minority populations remains pivotal in ameliorating the epidemic as a whole.

In December 2008, a Task Force of the American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists and Food Information Council proposed promoting small changes in diet and physical activity as a new strategy for weight loss. [7] The rationale behind this approach is that most adults gradually gain weight due to a small daily discrepancy between their energy intake and energy expenditure. This “energy gap” can be eliminated by small sustained behavioral changes that reduce intake by about 100 –200 kilocalories a day. [7–12]

To date, the small change approach has shown promise in several small scale quasi-experimental studies and randomized controlled trials [13–20] These studies have shown that the small changes approach can result in modest weight loss (− 2.6 to − 5.3 kg), weight loss maintenance at 12 months and be equally effective regardless of mode of delivery (i.e.: phone, in-person, leaflet, group meetings) or interventionist (i.e. clinicians vs. para-professional staff).

The purpose of this paper is to describe the design and rationale of the SCALE study (Small Changes and Lasting Effects). Among Black and Hispanic adults in two low income New York City neighborhoods, SCALE is a five year study aimed at testing a small change (SC) intervention combined with physical activity and induction of positive affect/ self-affirmation versus a SC intervention alone. Positive affect has been shown to help motivate initiation and maintenance of healthful behavior changes in patients with chronic disease. Self-affirmation techniques can enhance self-concept, and when performed prior to delivering threatening health messages, have been shown to assist people in processing self-relevant negative information. [21–24]

The recruitment of participants and delivery of all aspects of the intervention was conducted by community health workers. The primary outcome of SCALE is clinically meaningful weight loss (> 7%) at 12 months. The study goals were set based on the results from the Diabetes Prevention Program. In DPP, Latino men and women, and Black men in the lifestyle intervention group were able to achieve 6–7% weight loss. Black women were less successful at about 4%. [25] Given the high burden of diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the SCALE study populations we felt a clinically meaningful weight loss target was appropriate.

By partnering with community based organizations and ambulatory care networks we hope to gain a deeper understanding into the target population’s knowledge and preferences for the small change approach, explore complex social interactions and influences on eating and physical activity behaviors, and learn practical next steps for wide scale implementation and sustainability.

2. Design and Methods

2.1 Study Aims

The SCALE trial is one of seven Obesity Related Behavioral Intervention Trials (ORBIT) supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute focused on the translation of basic behavioral and social science discoveries into effective behavioral interventions for obesity management.[26]

We used a three-phase, mixed-methods translational approach termed EVOLVE— Explore Values, Operationalize and Learn, and eValuate Efficacy in developing the SCALE intervention. [27] The EVOLVE methodology offers advantages in developing behavioral interventions for use in chronic disease. In particular it addresses the issue of behavioral interventions being less efficacious once placed in real world settings. While cultural adaptations serve to increase the reach of an intervention the lack of fidelity standards for post-hoc intervention modification usually leads to mixed results. EVOLVE represents one strategy that can be used to create more broadly applicable evidence-based interventions from the beginning, thus limiting the need for later adaptations. The three phases of the SCALE project consisted of Phase I a qualitative phase, Phase II a pilot test and Phase II a randomized controlled trial.

Phase I: Qualitative Study to Explore Values

The specific aim of phase I was to gain a better understanding of the cultural, social, and psychological factors that could impact the target population’s day to day use of thirteen research-based small change eating strategies. The strategies as listed in Table 1 were found to have the greatest adherence rates and ease of implementation in a national online healthy eating and weight loss program. [28] The strategies are phrased in an active form and are accompanied by suggestions that briefly explain how the change may result in consuming fewer calories and hence weight loss. [29]

Table 1.

Small Change Eating Strategies

| Strategy (description) | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Use Smaller Plates - Use a 10 inch plate for the main meals | Package, serving and dishware size all influence how much people eat. Adults eating on a larger plate or bowl have been shown to consume on average > 30% more than aged matched controls eating on a smaller size plate or bowl [30–32] |

| Half-Plate Rule– when eating the main meal of the day half the plate should be vegetables and/or fruits and the other half protein and starch. | Increases percentage of lower density foods being consumed while still maintain volume and satiety stay high [33] |

| Keep Serving Dishes on the Counter - Leave no bowls of food on the table (except salad). | Moving from the table to fill plate interrupts eating scripts [32] |

| Relocate Snack Food to Inconvenient Location - Put snack food away in an out of sight hard to reach location. | Discourages frequent snacking [34] |

| Do Not Eat When the TV is On -Do not eat your main meals while watching TV. | Encourages more accurate monitoring of what is eaten [35, 36] |

| Eat Breakfast Daily - Make sure you eat breakfast each morning. If possible eat a hot breakfast | Reduces likelihood of snacking and overeating at lunch; increases protein [28] |

| Use the Fruit + Vegetable Rule -At every dinner or lunch eaten at home, place both a fruit and a vegetable on the table. | Increases percentage of fruit and vegetables being consumed [32] |

| Use the Fruit-Before-Snack Rule - Only eat a between-meal snack if you eat a fruit first . | Inconvenience reduces snacking of high calorie dense foods [37] |

| Using the Equal Water Rule-Drink 12 ounces of water for every can or glass of soft drink. | Is believed to reduce volume of soft drinks consumed [33] |

| Limit Fast Food - Limit fast food to emergencies; prepare food whenever possible. | Fast food has high caloric density; limiting fast foods may reduce overeating [33] |

| Don’t Skip Meals - Bring fruits and vegetables along if you can’t sit down to eat | Reduces overeating and snacking due to hunger before meals. [28] |

| Eat at Home - Eat your main meal at home at least 6 days a week. | May reduce the amount of calories consumed at a meal [28] |

| Stop Clean Plate club - Leave some food on the plate | May reduce overeating (32) |

Phase II: Pilot Study to Operationalize and Learn

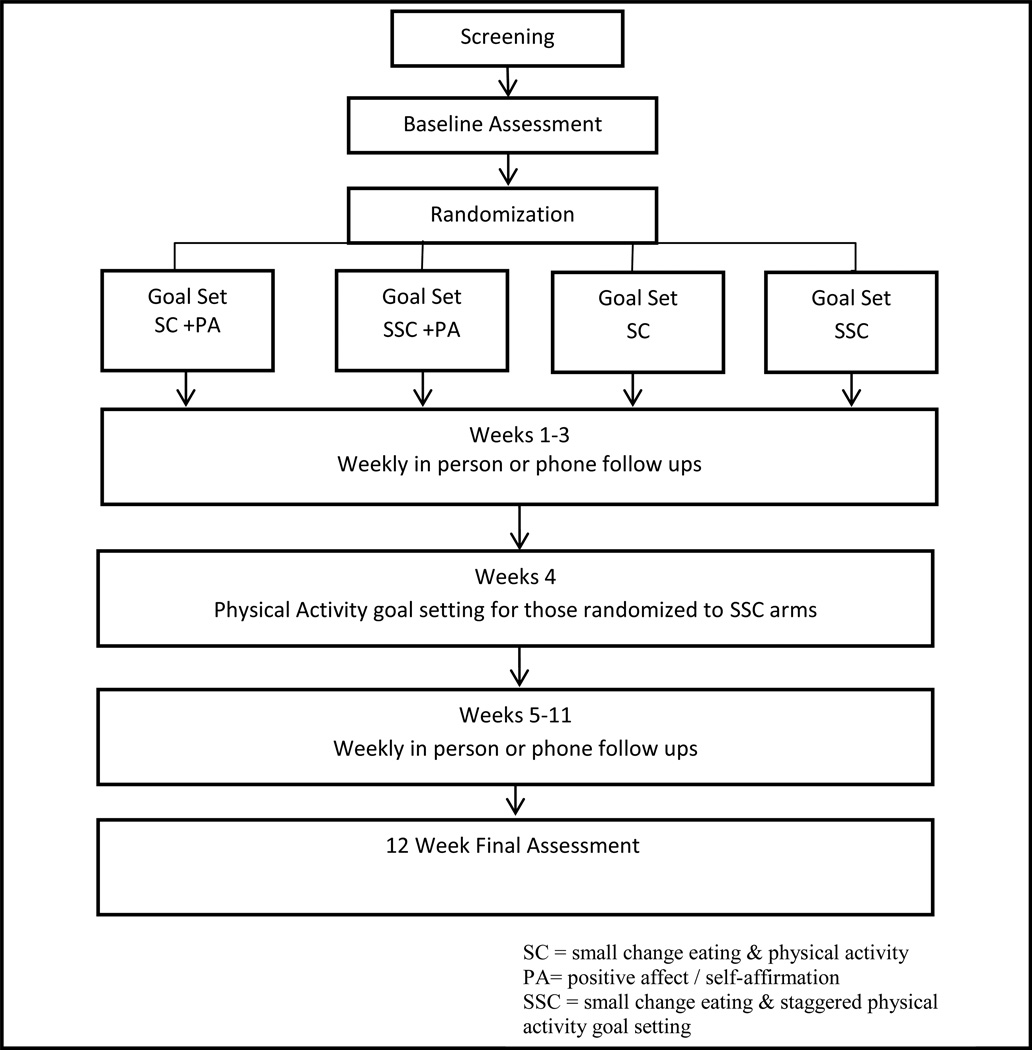

The aim of the pilot phase was two-fold: 1) to evaluate the feasibility of conducting the small change intervention in the target population using community health worker; and 2) to compare differences in adherence at 12 weeks among participants who were randomized to making two small changes at enrollment (eating and lifestyle physical activity) versus a staggered implementation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of pilot study

Phase III. Randomized Control Trial to eValuate Efficacy

The aim of phase III was to evaluate the efficacy of a small change eating/lifestyle activity/positive affect/self-affirmation intervention vs. a small change eating/lifestyle activity intervention in achieving sustained changes in weight. The primary outcome is ≥7% weight loss at 12 months; however, total weight loss and percent weight loss are also being evaluated. The secondary outcomes are the number of eating behavior changes sustained at 12 months, and within-patient change in the Paffenbarger Physical Activity and Exercise Index.[38]

2.2 Participants

Participant recruitment was done in partnership with Renaissance Health Care Network and the Lincoln Center for Community Collaborative Research (LCCCR). Renaissance Health Care Network, a member of the New York City Health & Hospitals Corporation and a member of the Generations+/Northern Manhattan Health Network has over 120,000 visits adult visits per year for basic preventive and primary care services. Overall, 90% of the patients seen are Black or Latino, 70% are women and over half are overweight or obese. The LCCR based at Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center is a network of community based organizations, community residents, and physicians from the South Bronx and Harlem dedicated to reducing and eliminating health disparities in communities of color through outreach, education, and community-driven research. The general medical practice at Lincoln Medical Center has approximately 50,000 annual adult medicine visits. About 70% of the patients are Latino, 25% Black, and 27% overweight or obese. Two of the SCALE investigation team members, Drs. Kanna and Michelin, were in clinical administrative roles at the clinical partnership sites. The details regarding the engagement of the community based organizations have been previously published. [39]During all phases participant recruitment was done via flyers and direct referrals from health care providers and participating community site leaders.

All participants were screened in person by community health workers (CHWs). Inclusion criteria were age ≥21 years of age, measured BMI 25–50 kg/m2, and self-identification as Black and/or Hispanic. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, or planning to become pregnant within the year, participating in another weight loss program or trial, intention to undergo weight loss surgery within the year, untreated mental illness, untreated thyroid disease, active cancer, active eating disorder (anorexia or bulimia), advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease on dialysis or the inability to control meal content (for example living in an institutional setting). Recruitment of participants for each phase was mutually exclusive. Enrolled participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Rights in Research at the Weill Cornell Medical College and Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center of the Health and Hospital Corporations of New York City. An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviewed the protocol prior to the initiation of each phase as well as reviewed adverse events throughout the study.

2.3 Procedures

2.3.1 Phase I: Qualitative Study to Explore Values

Six focus groups comprised of about 20 participants each were conducted from September 2009 to May 2010. All groups were conducted using a standardized script by two trained moderators, of whom one was bilingual. At each group session the thirteen small change eating strategies were presented, participants were asked to vote via ballot for the top six strategies that they felt could be easily adopted by themselves, their family and/or social network. Thereafter the top six strategies were discussed in detail. Each group session lasted approximately 2 hours. This methodology was implemented to ensure that in depth discussions could be conducted about the most preferred strategies in a reasonable time frame versus a limited discussion of all thirteen. Upon completion participants completed a brief survey that included questions on basic demographics, general health,and eating behaviors. Participants were given a $20 gift card as compensation for their time.

2.3.2 Phase II: Pilot Study to Operationalize and Learn

Two months prior to the implementation of the pilot phase community health workers were hired and trained by our community partner, Northern Manhattan Perinatal Partnership (NMPP). NMPP has a long history of running CHW programs in the Harlem Community and is a member of the CHW Network of NYC. All candidates were also interviewed by the investigators to determine suitability for the project. CHW’s were required to be bilingual, reside or have worked in the target communities, and have had experience in the health field. Four CHW’s were initially hired and underwent an extensive (140 hours) training by an established CHW program and the investigation team. The training program topics included health promotion & education, health advocacy, care coordination, communication skills, interpersonal skills, ethics & professionalism, crisis intervention, health care systems, and community resource building. The investigational component of the training was based on an 81 page manual developed for SCALE that covered topics on the ethics of conducting human research, chronic illness and prevention, and all study training materials. Satisfactory completion of the training was assessed by the investigators and peer evaluations of video recorded role playing exercises. All CHW activities were dually supervised by the NMPP program and SCALE study coordinators. The pilot phase was conducted between August 2010 thru July 2011.

After screening, eligible participants were consented and completed a baseline assessment comprised of a written survey and anthropomorphic measures of height (Stadiometer SECA model 214), weight (SECA SACEL 812 High Capacity Digital Floor Scale) and waist circumference (standard tape measure) using a standardized protocol. Participants were then randomized to one of four treatment arms (Figure 1). The primary outcome of the pilot was adherence at 12 weeks to the small change eating and physical activity goals. Adherence was defined as the proportion of days in which the participant was successful in completing their set goal and expressed as a percentage. In the pilot, we were also particularly interested in evaluating differences in adherence rates at 12 weeks between those participants making two behavioral changes (SC) at the same time versus a staggered implementation (SSC). Participants in the staggered small change group set their eating strategy goal at initiation and then 4 weeks later set their physical activity goal. While multi-behavior interventions have the potential to offer greater health benefits they may also overwhelm and result in poor adherence. Sequencing change goals is one strategy that may facilitate greater adherence and overall change. [40] The positive affect and self-affirmation intervention were included in the pilot phase in order to familiarize the CHW’s with the methodology of teaching participants how to use the script as well as performing weekly intervention checks on its use.

SC Intervention

A goal setting interview was conducted among all participants upon completion of the baseline assessment. Participants unable to complete both on the same day were given the option to schedule a follow up in person session within 7 days to complete the goal setting interview. Each of the four randomization groups received the small change eating intervention, with half of the group assigned to a staggered small change implementation (SSC) with and without the positive affect/self-affirmation intervention (PA).

Using a standardized protocol, CHWs coached participants on the selection of one of the six small change eating strategies and a self-selected physical activity goal. The six small change strategies (bolded in Table 1) represent those strategies with the highest cumulative scores from the six phase I focus groups. CHW’s then probed participants about factors that could enable or prevent them from using each strategy on a daily basis. Participants were then asked to select one strategy for which they had a confidence level of 8 or higher in their ability to use the eating strategy most days of the week (5 or more days). Participants signed a behavioral contract that described the eating strategy selected (i.e.: make half of main meal vegetables), when they would do it (i.e.: at dinner) and for how long (i.e.: 5 days a week for 12 weeks). Next participants physical activity level was assessed using the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Index.[38]. Using this CHW’s worked with participants to set a physical activity goal that increased the increment of time or intensity of their current activities. A behavioral contract was similarly established for the physical activity goal.

Small Change Follow Up Sessions

At each weekly individual follow up the assigned CHW reviewed participants adherence to their small change behavioral goal, discussed facilitators and barriers to goal completion, and assisted participants in overcoming barriers to their goals using a five step problem solving model. [41] At the conclusion of the problem solving session the option to modify the goal or continue it as long as their confidence level remained above 8 was provided. At 4 weeks, among participants who successfully met their target goal weekly, CHW’s coached on the addition of a new small change eating strategy and/or another incremental increase in the time or intensity of the current physical activity goal. The final follow-up was conducted in person at 12 weeks. The primary outcome of the pilot phase was the number of eating and physical activity behaviors that were adopted and sustained at 12 weeks. Change in body weight was a secondary endpoint. In addition, at the closing interview brief open ended questions were asked to build a better understanding of participant’s barriers and facilitators to successful behavior change and their experiences with each strategy.

Theoretical framework for Small Change Intervention

SCALE’s small change intervention is informed by the Social Cognitive Theory.[42] The theory illustrates the relationship between the behavior (small changes in daily lifestyle patterns), the person (self -efficacy, positive and negative affect, social norms, and stress), and the environment (social support and social network). In this model self-efficacy is a key mediator of behavior change. People with high self-efficacy keep trying when they hit obstacles to change, while those with low self-efficacy are more likely to give up. Achieving small lifestyle changes could enhance self-efficacy and thus stimulate people to maintain the current behaviors while adding new ones. Recent results from our completed randomized trials, demonstrated that the constructs of positive affect and self-affirmation increased behavior specific self-efficacy in the trials.[22, 24, 43] These two constructs helped patients in those trials overcome the adverse behavioral impact of negative psychosocial changes such as increased stress or decreased support on their goals. [22] The SCALE project evaluates the impact of these two constructs positive affect/self-affirmation (PA/SA) on adherence to the small change intervention (SC) compared to adherence to the SC intervention alone.

Positive Affect and Self-Affirmation Intervention

Positive affect refers to a mild happy feeling state which has an important impact on people’s thinking, motivation, [44] behavior and ability to cope with stressful events. [45] Self-affirmation, a strategy to increase self-efficacy in threatening situations, may enhance people’s ability to overcome any negative expectations of their own ability to stay resolved to practice positive health behaviors. [46] These two constructs were formulated into a simple teachable self-motivating script.[23] Participants in the positive affect/self-affirmation intervention group were asked to identify small things that make them feel good and were told that, “Thinking about these small things that make you feel good may help you to overcome challenges and improve your health”. They were asked to think about these things when they first wake up in the morning and throughout their day. For example, some participants induced their own positive affect every day by taking a moment to enjoy beautiful things, such as the sun rising. For the self-affirmation component of the intervention, participants were asked to think of a particular proud moment in their life and were told that thinking about this moment could help them overcome challenges in carrying out their new health behavior. For example, participants used self-affirmation to overcome obstacles by remembering how they had achieved another goal in the past. At each follow-up, participant’s daily use of the positive affect and self-affirmation intervention was assessed via a recall of number of days used during the past week.

2.3.3 Phase III Randomized Control Trial to eValuate Efficacy

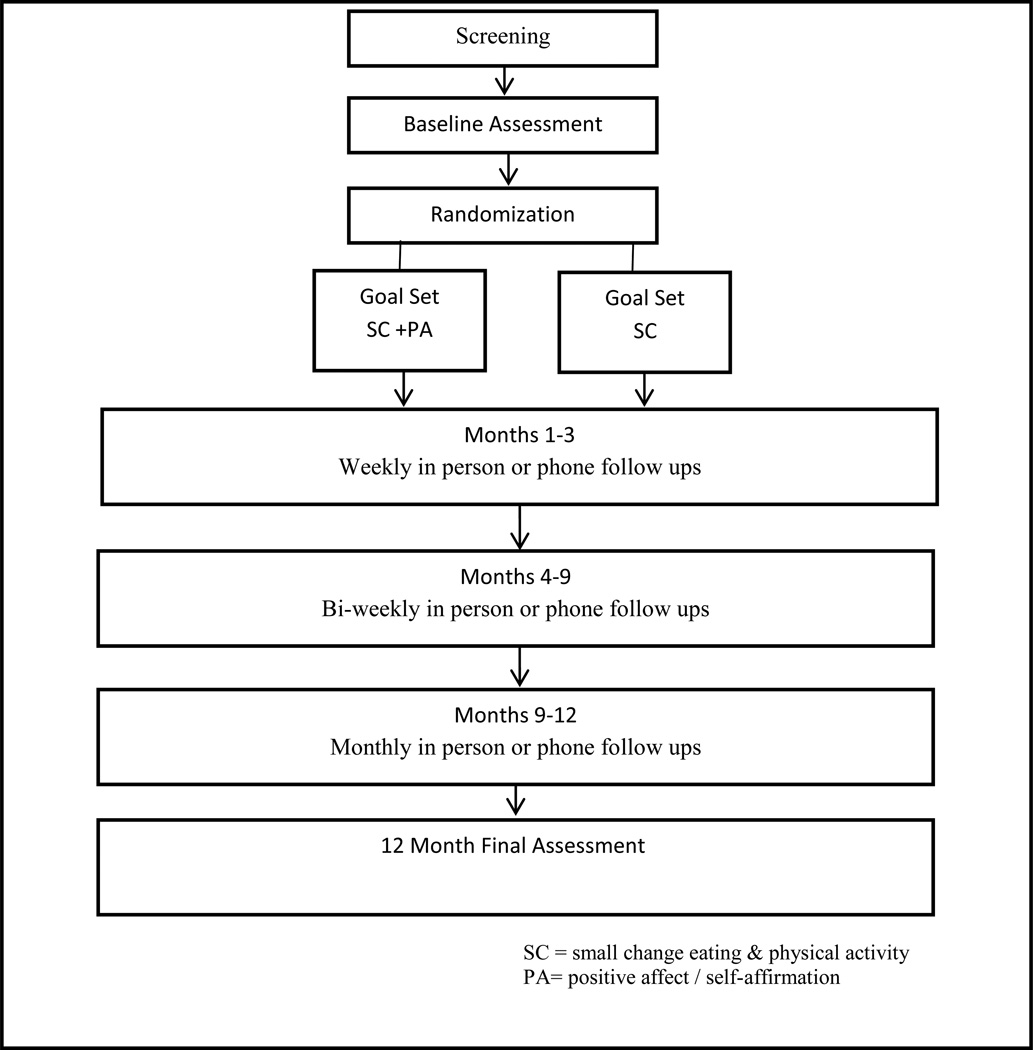

Participants were stratified into three groups. Group I represented individuals recruited to participate in the study by themselves but asked to recommend the name of a social network member who might be interested in participating in the study as well. Group II participants had one additional eligibility criteria in that there needed to be at least one family member (age 13 or older) residing in the home with them. Group III represented individuals recruited at a participating community based organization where members of the entire organization were invited to enroll. At enrollment participant’s height, weight and waist circumference were measured. After completion of the baseline assessment participants were randomized to one of two treatment arms. If a social network member was recruited they were placed in the same intervention arm that the index participant was randomized to in order to prevent contamination. The same rationale applied to community sites, the site was the unit of randomization. These three recruitment groupings were designed to assess whether involvement of different forms of the social network would enhance the efficacy of the intervention. A detailed description of the flow of participants from screening to completion at 12 month follow up is shown in Figure 2. The baseline assessment and goal setting interview were conducted in one session. Follow up sessions were conducted on the phone or in person, based on the participants preferences weekly during months 1–3, biweekly during months 4 to 9 and monthly during months 10–12. At each follow-up CHW’s assessed for adherence to the eating and physical activity strategies as number of days in the past week that a participant was able to do each one. For those randomized to the PA/SA CHW’s also assessed how many days in the past week the participant used each component. At month 3 all participants were given an individualized scale for self- monitoring of their weight. They were asked to check their weight at least monthly and report the weight to their CHW during the regular follow-up. The final assessment was done in person. Table 3 depicts the measures obtained at each follow up during the RCT.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of randomized control trial design

Table 3.

Pilot Findings Applied to Phase III: Randomized Control Trial

| Revisions Made to Methods | |

|---|---|

| Recruitment and Retention |

|

| Intervention |

|

2.3.4 Data Analysis Plan

Phase I - Analysis of qualitative data from the focus group transcripts was aided by the use of the Ethnograph® qualitative software by three investigators (coders) and systematically analyzed line by line to identify specific concepts. Concepts were assessed during an iterative process to discern specific categories based on similarities and differences to each other or relationships to certain phenomenon. Categories were then grouped according to over-arching themes. Three additional investigators (corroborators) independently reviewed all transcripts. Each coder-corroborator pair met to compare and discuss their independently determined categories. The three coder-corroborator pairs then met and through consensus arrived at the final set of categories and themes. Phase II - Descriptive statistics were used to calculate means and proportions. We assessed the daily adherence to the eating strategies, and physical activity goals using a binomial regression model. Weight loss will be analyzed as >7% loss and the actual % of weight loss using logistic and linear regression. We will identify factors (i.e., stress, family and work stress, social support, depressive symptoms) that may reduce or enhance intervention effectiveness across participants using regression methodologies. Phase III - Power analysis was conducted for phase III using an adaptive sampling design. For Phase III we proposed to deliver the (small changes +PA/SA) intervention to twice as many participants versus the small change intervention alone. We initially planned to recruit six different community sites but in February 2012 an adjustment to recruitment numbers was made based on the overwhelming interest of participants from one of the community sites. Thus the number of community sites was reduced to five. Based on testing the Time X Group interaction in a MANOVA, allowing for heterogeneous variances and serial correlations, 5% level tests, and lost to follow-ups during the trial a total of 318 participants would need to be enrolled in order to have a power of 80%. Given that participants were stratified into three recruitment groups we determined that in groups 1 and 2, 56 subjects for each group would need to be enrolled in the intervention arm with 28 subjects each in the control arm. A total of 150 subjects would need to be enrolled across the five community sites. Power analyses were conducted using the R statistical language. [44]

3.1 Results

3.1.1 Phase I: Qualitative Study to Explore Values

Participant Characteristics

A total of 67 participants were enrolled. More than half of participants (60%) self-identified as Hispanic. The mean age of participants was 54 years; 72% were women. Overall, 42% were married, and 46% had one or more children residing in their household; 74% had a high school education or more, and 30% were currently employed. The groups mean measured BMI was 34 kg/m.2. 74% of participants reported they weighed too much and 73% had been advised by a health care provider to lose weight. Only 27% of participants reported eating five or more servings of fruits and vegetables daily. More than half (53%) described their health as fair or poor.

Application of Qualitative Findings

Using their previous experiences as a point of reference participants discussed the barriers and facilitators to utilizing the thirteen small change eating strategies. Six strategies were selected as the most viable strategies for future implementation. These findings were used to enhance two key aspects of the small change intervention: 1) Creation of a culturally-relevant information workbook based on real life experiences about weight loss and its challenges that was given to all participants at the goal setting session of Phase II and Phase III. The workbook chapters were focused on addressing the concept of small behavior changes that may be better suited for weight loss long term, the barriers and facilitators to implementing each strategy, creating a personal behavioral contract, initiating lifestyle-physical activity and learning how to use your social network for support. Participants randomized to the positive affect/ self-affirmation component of the intervention had an additional chapter on “Staying Positive.” 2) To refine the small change eating strategies. The six strategies with the highest cumulative scores across the six focus groups were modified based on the focus group discussions and implemented in the pilot phase.

3.1.2 Phase II: Pilot Study to Operationalize and Learn

Participant Characteristics

Community health workers screened a total of 275 people of which 214 were eligible for study participation. 102 participants consented and were enrolled. Nine participants were lost prior to the goal setting interview. A total of 93 participants completed goal setting and were randomized. Twelve week follow ups were completed on 64 participants. The overall mean age of participants was 50 (SD ± 12.6). The majority of participants were women (75%), 56% Hispanic, 48% black, 42% had never been married, and 22% of participants did not finish high school. Approximately a third of participants had hypertension (33%) and 20% had diabetes. More than half (78%) had been told by a doctor or family member (74%) to lose weight. A vast majority of participants (88 %) had made a previous attempt at losing weight. The mean weight on enrollment was 207 lbs. (SD ±41) with a mean BMI of 34.5 (SD ± 6).

Applying Pilot Findings

As a result of the pilot phase we made changes with regards to our recruitment and retention methodology, as well as the small change intervention (Table 5).

Recruitment and retention

First starting with our recruitment/ retention methodology we learned that it was best to do the goal setting and randomize participants at the same time. In the pilot study allowing participants to separate the goal setting interview from the baseline assessment resulted in the loss of nine participants after completion of the baseline assessment. In order to reduce the duration of the face to face enrollment process an online enrollment survey was developed. Completion of the baseline survey online reduced the face –to-face time for the goal setting and randomization interview by approximately 30 minutes. We also experienced a 31% lost to follow up rate over the 12 week period which is comparable to most weight loss trials. Since there was no significant difference in drop-out rates across sites we incorporated a previously developed motivational interviewing technique used to improve retention in behavioral weight loss trials at the community sites. [69] On the individual level we revised the informed consent process to include information on the importance of study completion for developing weight loss strategies that work for minority populations. Lastly we adjusted the CHW’s work schedules to permit for more flexibility in following up participants during evening and weekend hours. Follow-ups were conducted via the telephone or in person at a location named by the participant (i.e.: home visit, church, participant work site). Metro cards were made available for participants who expressed financial barriers to completing follow up visits or the final close out.

Intervention refinement

In this phase, all participants made initial contracts for eating behavior change, and half were randomized to either immediate contracting for a lifestyle physical activity change or lifestyle physical activity change after four weeks. We found no difference in adherence or weight loss between the immediate or staggered physical activity groups thus for the RCT participants set goals for both at the same time. While in the pilot participants were only presented with six of the small change eating strategies this was revised and ten total strategies were presented for the RCT. The four strategies added to the RCT had the next highest cumulative ranked scores from the focus groups. The rationale for expanding the strategy options was secondary to the pilot finding that the most important factor to adherence and weight loss was participant’s high self-efficacy for the selected strategy. The key elements in strategy selection were 1) Participants needed to understand the strategy and 2) The strategy needed to be a strategy that they were not already doing and were confident they could maintain. This led to the development of a strategy selection matrix (see Table 4) for which CHW’s guided participants in the selection of at least three strategies that might best address their current eating challenges. For example for participants for whom snacking in between meals is a challenge the strategy of not purchasing snacks or moving snacks to an inconvenient location would be recommended as the best strategy to initiate as long as the participant expressed a self-efficacy of 8 or greater. Next, participants were encouraged to select one strategy at a time. CHW’s coached them on the benefit of building their self-efficacy thus they were told “when you’ve got this down, you can add another strategy.” Thus in the trial participants had to demonstrate adherence to a strategy for at least four consecutive weeks before a CHW would introduce the idea of adding on an additional strategy. There was no cap set on the number of strategies that a participant could utilize over the 12 month period. Coaching scripts were developed for the CHW’s to address common barriers that evolved during the pilot phase such as teaching participants how to enlist the support of household members when the participant was not the primary food shopper or preparer and found that the foods being brought in the home were making it difficult to adhere to their selected eating strategy. Lastly the investigators developed a checklist to monitor the fidelity of the intervention at different stages (i.e. enrollment, follow up and study closure.)

Table 4.

Small Change Eating Strategy Matrix

| Eating Challenge | Small Change Solution | Do You Currently do Any of These 6 Days of the Week? |

|---|---|---|

|

□ Prepare Main Meal at Home | Yes_____ N/A_____ No_____ |

|

□ Take Time for Meals |

Yes_____ N/A______ No_____ |

|

□ Drink water in place of sweetened beverages | Yes_____ N/A_____ No_____ |

|

□ Eat a Fruit or Vegetable Before Snacking |

Yes_____ N/A_____ No_____ |

|

□ Eat breakfast | Yes_____ N/A_____ No _____ |

|

□ Turn off the TV during meals |

Yes_____ N/A_____ No _____ |

|

□ Don’t buy snack food | Yes_____ N/A_____ No _____ |

|

□ Hide snacks in an inconvenient place | Yes_____ N/A_____ No _____ |

|

□ Eat all main meals on a 10-inch plate | Yes_____ N/A_____ No _____ |

|

□ Half of what you eat for the main meal should be vegetables |

Yes_____ N/A_____ No _____ |

4. Phase III Randomized trials to eValuate Efficacy

The recruitment for Phase III began in August 2011 and ended in April 2013. We screened 644 participants of which 12% were ineligible. The most common reasons for ineligibility was not meeting the BMI criteria, severe medical conditions such as heart disease and not having independent control over meal content. Among the 560 eligible participants 405 were enrolled and randomized. At the time of this publication the analysis of the randomized controlled trials is ongoing and will be presented in future publications.

5. Discussion

The SCALE study was designed to test a small change weight loss behavioral intervention in a minority population in two low income neighborhoods of New York City. SCALE is unique in several ways. First the project used a three-phase, mixed-methods approach termed EVOLVE—Explore Values, Operationalize and Learn, and eValuate Efficacy in refining and developing the final intervention. Our investigation team felt that this approach was particularly critical to implementing the intervention in our target population. Ethnic minorities are overrepresented among the overweight and obese population. Most weight-loss interventions designed for the general population have been less successful among ethnic minorities and thus the pressing need to develop more effective interventions for this group. Studies have demonstrated the importance of taking into account culturally mediated factors in the design and implementation of treatment interventions.[6, 70, 71] In the first phase of SCALE we gained insight into the current weight loss practices of members of the target community. We then used those participants as content experts in the discussion of the thirteen small change strategies. One example of how culturally mediated factors influenced strategy selection among the groups was the discussion of the “Stop the Clean Plate Club” strategy among the Hispanic focus groups. One participant summarized it this way “As a Hispanic my mother didn’t allow that…and I would imagine this goes for most of you here in your homes your mother, your grandmother would not allow you to leave anything on your plate. You eat what you are given. You have to eat all of it.” The end result of the focus groups was that six small change eating strategies with the highest cumulative votes were selected as the strategies for implementation and testing in the pilot phase. Given the short duration of the pilot the primary outcome was not weight loss but rather adherence to the small change strategies.

Second, SCALE was designed to offer all participants the small change intervention. Thus the control arm is not the typical cohort that receives educational handouts or “standard of care”. By the intervention being personalized, follow ups being participant centered in timing and location, and delivered by community health workers all participants equally had a better chance at achieving their goals.

Third, we are testing the intervention among three participant groups in order to assess the role of social ties on weight loss. To our knowledge there have not been any behavioral weight loss studies that have used such an approach. Social network factors, although generally embedded in both individual and environmental factors, are less often directly integrated and studied within weight loss intervention trials. This may be secondary to uncertainty regarding how to target and leverage the impact of social networks on eating and activity patterns in order to promote weight loss. Thus more contextual data is needed on the function of social networks on the weight loss efforts of overweight and obese adults in order to identify the characteristics of network members associated with weight loss success, particularly among Black and Hispanic adults.

Fourth, the SCALE study seeks to understand and work within real world conditions, community and primary care based settings where the fight against obesity is happening every day. Context plays a central role in obesity research. Developing more in depth understanding of how external factors (e.g. social, cultural, and built environment) influence individual eating and physical activity patterns are critical to developing an intervention that works in the real world. Furthermore the outcome variables of acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, and sustainability are all equally important outcomes in SCALE.

Our study is not without limitations. Phase II provided our first introduction into the issues of attrition felt by many in behavioral weight loss interventions. Our early 31% lost to follow up rate at 12 weeks and the closing of some participants at 21 weeks rather than the desired 12 weeks provided a basis for developing alternative strategies for decreasing lost to follow up rates in the trial. In addition while the results from our study may not be applicable to other populations as our study focuses solely on an urban minority population, the mixed methods approach (EVOLVE) is one that lends itself to the development of more effective health related behavioral interventions in any population.

Table 2.

SCALE Schedule of Measures

| Measurement | Months Administered |

Method of Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Measures | ||

| Age | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Gender | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Race | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Ethnicity | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Address | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Marital Status | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Employment Status | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Type of Occupation/Work Hrs | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Household members | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Medical Insurance | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Medical History | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Medication List | 0 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Weight History | 0,12 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Food Insecurity | 0, 12 | Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals |

| Marin Acculturation Scale | (CSFII)[47] | |

| Clinical Measures | ||

| Weight | 0, 4–12 | On site assessment |

| Height | 0, 12 | On site assessment |

| BMI | 0, 12 | On site assessment |

| Waist Circumference | 0, 12 | On site assessment |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0 | Charlson Comorbidity Index Questionnaire[48] |

| Medication Lists | All | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Behavioral Measures | ||

| BRFSS (Fruits & Vegetables) | 0, 12 | BRFSS Questionnaire[49] |

| Food Choice Coping Strategies | 0, 12 | Food Choice Coping Strategy Questionnaire[50] |

| Eating Challenges | 0, 12 | Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire [51–53] |

| Home Eating Environment | 0, 12 | Internally developed questionnaire |

| Paffenbarger Physical Activity | All | Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire[54, 55] |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 0, 12 | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Questionnaire[56] |

| Goal Setting | All (if needed) | Internally developed guide |

| Problem Solving | All (if needed) | Problem Solving Therapy[57] |

| Goal Adherence | All | Number of Days goal(s) met |

| Psychosocial Measures | ||

| Perceived Stress | All | Perceived Stress Scale Questionnaire[58] |

| Wheaton Chronic Stress | 0 | Job Content Questionnaire[59] |

| Time Scarcity | 0, 12 | Time Scarcity Indicators [60] |

| Mastery | 0, 12 | The Mastery Scale [61] |

| SRRS | 0, 12 | Social Readjustment Rating Scale [62] |

| Trait Affect | 0, 12 | PANAS SCALE[63] |

| PHQ-9 | 0, 12 | PHQ-9 Questionnaire[64] |

| MOS Social Support | 0, 12 | MOS Social Support Survey[65] |

| Social Network Assessment | 0, 12 | Convoy Model [66][67] |

| Social Network Weight Perception | 0, 12 | Stukard Scale[68] and Internally developed |

| Personal Weight Perception | 0, 12 | quesntionnaire |

| Positive Affect / Self-Affirmation | All | Stunkard Scale and Internally developed questionnaire |

| Internally Developed Questionnaire[23] | ||

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of Project SCALE (Small Changes and Lasting Effects) and is collaboration between Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University, Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center, Renaissance Health Care Network, Abysinnian Baptist Church, First Baptist Church, Metropolitan Methodist Community Church, Congrecion De Iglesia, and St. Luke’s Roman Catholic Church. This study was supported by a grant from the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI UO1 HL097843). In addition Drs. Charlson and Phillips-Caesar are investigators also supported by the Center for Excellence in Health Disparities Research and Community Engagement NIMHD P60 MD003421-02.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kumanyika SK. Special issues regarding obesity in minority populations. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:650–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts M, Kerker B, Mostashari F, Van Wye E, Thorpe LE. Obesity and Health; Risks and Behaviors. New York City Vital Signs. 2005;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523–1529. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumanyika S. Ethnic minorities and weight control research priorities: where are we now and where do we need to be? Prev Med. 2008;47:583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumanyika S, Grier S. Targeting interventions for ethnic minority and low-income populations. Future Child. 2006;16:187–207. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumanyika SK, Whitt-Glover MC, Gary TL, Prewitt TE, Odoms-Young AM, Banks-Wallace J, et al. Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4:A112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill JO. Can a small-changes approach help address the obesity epidemic? A report of the Joint Task Force of the American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:477–484. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill JO, Peters JC, Wyatt HR. Using the energy gap to address obesity: a commentary. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1848–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill JO, Peters JC, Catenacci VA, Wyatt HR. International strategies to address obesity. Obes Rev. 2008;(9 Suppl 1):41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill JO. Understanding and addressing the epidemic of obesity: an energy balance perspective. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:750–761. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadden TA, Crerand CE, Brock J. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28:151, 70, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Wilson C. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2226–2238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutes LD, Winett RA, Barger SD, Wojcik JR, Herbert WG, Nickols-Richardson SM, et al. Small changes in nutrition and physical activity promote weight loss and maintenance: 3-month evidence from the ASPIRE randomized trial. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:351–357. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damschroder LJ, Lutes LD, Goodrich DE, Gillon L, Lowery JC. A small-change approach delivered via telephone promotes weight loss in veterans: results from the ASPIRE-VA pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:262–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutes LD, Daiss SR, Barger SD, Read M, Steinbaugh E, Winett RA. Small changes approach promotes initial and continued weight loss with a phone-based follow-up: nine-month outcomes from ASPIRES II. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26:235–238. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090706-QUAN-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutes LD, Dinatale E, Goodrich DE, Ronis DL, Gillon L, Kirsh S, et al. A randomized trial of a small changes approach for weight loss in veterans: design, rationale, and baseline characteristics of the ASPIRE-VA trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinn C, Schofield GM, Hopkins WG. A “small-changes” workplace weight loss and maintenance program: examination of weight and health outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54:1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182480591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zinn C, Schofield GM, Hopkins WG. Efficacy of a “small-changes” workplace weight loss initiative on weight and productivity outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54:1224–1229. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182440ac2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damschroder LJ, Lutes LD, Kirsh S, Kim HM, Gillon L, Holleman RG, et al. Small-changes obesity treatment among veterans: 12-month outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings DM, Lutes LD, Littlewood, Kerry, DiNatale, Emily, Hambidge, Bertha, Schulman, Kathleen EMPOWER: A randomized trial using community health workers to deliver a lifestyle intervention program in African American women with Type 2 diabetes: Design, rationale, and baseline characteristics. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;36:147. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boutin-Foster C, Scott E, Rodriguez A, Ramos R, Kanna B, Michelen W, et al. The Trial Using Motivational Interviewing and Positive Affect and Self-Affirmation in African-Americans with Hypertension (TRIUMPH): from theory to clinical trial implementation. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Wells MT, Peterson JC, Boutin-Foster C, Ogedegbe GO, Mancuso CA, et al. Mediators and moderators of behavior change in patients with chronic cardiopulmonary disease: the impact of positive affect and self-affirmation. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4:7–17. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0241-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Boutin-Foster C, Mancuso CA, Peterson JC, Ogedegbe G, Briggs WM, et al. Randomized controlled trials of positive affect and self-affirmation to facilitate healthy behaviors in patients with cardiopulmonary diseases: rationale, trial design, and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, Allegrante JP, Isen AM, Jobe JB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:322–326. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West DS, Elaine Prewitt T, Bursac Z, Felix HC. Weight loss of black, white, and Hispanic men and women in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anonymous NIH Launches Program to Develop Innovative Approaches to Combat Obesity [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson JC, Czajkowski S, Charlson ME, Link AR, Wells MT, Isen AM, et al. Translating basic behavioral and social science research to clinical application: the EVOLVE mixed methods approach. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:217–230. doi: 10.1037/a0029909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wansink Brian, David RJust, Collin RPayne. Mindless Eating and Healthy Heuristics for the Irrational. American Economic Review. 2009;99:165–169. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wansink B. Mindless Eating-Why We Eat More Than We Think. New York: Bantam-Dell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Kleef E, Shimizu M, Wansink B. Serving Bowl Selection Biases the Amount of Food Served. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wansink B, Wansink CS. The largest Last Supper: depictions of food portions and plate size increased over the millennium. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:943–944. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sobal J, Wansink B. Kitchenscapes, Tablescapes, Platescapes, and Foodscapes. Environment and Behavior. 2007;39:124–142. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wansink B. From mindless eating to mindlessly eating better. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Painter JE, Wansink B, Hieggelke JB. How visibility and convenience influence candy consumption. Appetite. 2002;38:237–238. doi: 10.1006/appe.2002.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu M, Wansink B. Watching food-related television increases caloric intake in restrained eaters. Appetite. 2011;57:661–664. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Painter JE, Wansink B, Hieggelke JB. How visibility and convenience influence candy consumption. Appetite. 2002;38:237–238. doi: 10.1006/appe.2002.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wansink B, Payne CR, Shimizu M. “Is this a meal or snack?” Situational cues that drive perceptions. Appetite. 2010;54:214–216. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:161–175. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hippolyte JM, Phillips-Caesar EG, Winston GJ, Charlson ME, Peterson JC. Recruitment and retention techniques for developing faith-based research partnerships, New York city, 2009–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10 doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prochaska JJ, Spring B, Nigg CR. Multiple health behavior change research: an introduction and overview. Prev Med. 2008;46:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Hoffman Z, Wells MT, Wong SC, Hollenberg JP, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect induction to promote physical activity after percutaneous coronary intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:329–336. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aspinwall LG, Tedeschi RG. The value of positive psychology for health psychology: progress and pitfalls in examining the relation of positive phenomena to health. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39:4–15. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Lynch M. Self-image resilience and dissonance: the role of affirmational resources. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64:885–896. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Townsend MS, Peerson J, Love B, Achterberg C, Murphy SP. Food insecurity is positively related to overweight in women. J Nutr. 2001;131:1738–1745. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Charlson ME. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:378. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.NHANES [Google Scholar]

- 50.Devine CM, Jastran M, Jabs J, Wethington E, Farell TJ, Bisogni CA. “A lot of sacrifices:” work-family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage employed parents. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Strien T, Frijters JER, Bergers GPA, Defares PB. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Strien T, Frijters JE, Roosen RG, Knuiman-Hijl WJ, Defares PB. Eating behavior, personality traits and body mass in women. Addict Behav. 1985;10:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(85)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blair AJ, Lewis VJ, Booth DA. Does emotional eating interfere with success in attempts at weight control? Appetite. 1990;15:151–157. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(90)90047-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Jr., Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albanes D, Conway JM, Taylor PR, Moe PW, Judd J. Validation and comparison of eight physical activity questionnaires. Epidemiology. 1990;1:65–71. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, Kamarck TW, Owens J, Lee L, et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Arean P. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3:322–355. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zukewich N. Work, parenthood and the experience of time scarcity. 2003 no. 89-584-MIE. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. Social networks in adult life and a preliminary examination of the convoy model. J Gerontol. 1987;42:519–527. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, Birditt KS. The convoy model: explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. Gerontologist. 2014;54:82–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stunkard AJ, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F. Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of obesity and thinness. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;60:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goldberg JH, Kiernan M. Innovative techniques to address retention in a behavioral weight-loss trial. Health Educ Res. 2005;20:439–447. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.James DC. Factors influencing food choices, dietary intake, and nutrition-related attitudes among African Americans: application of a culturally sensitive model. Ethn Health. 2004;9:349–367. doi: 10.1080/1355785042000285375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hovell MF, Mulvihill MM, Buono MJ, Liles S, Schade DH, Washington TA, et al. Culturally tailored aerobic exercise intervention for low-income Latinas. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22:155–163. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]