Abstract

Background

Total elbow arthroplasty for posttraumatic arthritis or nonunion has been associated with a high rate of complications. Bushing wear is a known complication, although the actual incidence is unknown because stress views of the elbow are not routinely performed. We evaluate incidence of bushing wear in total elbow arthroplasty using stress radiographs.

Methods

Eighteen patients underwent total elbow arthroplasty from 1997-2009 for posttraumatic arthritis or distal humerus nonunion using the third generation Coonrad-Moorey design. Eight patients met inclusion criteria and had an average age of 67 years and mean follow-up of 105 months. Radiographs were analyzed for bushing wear and implant loosening on standard and stress radiographs. Clinical outcome measures included the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire, Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS), overall patient satisfaction, range of motion, and complications.

Results

Rate of bushing wear was high, and stress views were five times more sensitive in detecting bushing wear (63%) compared to non-stress views (12%). Seventy-five percent of patients had a good or excellent MEPS. Range of motion slightly improved from pre- to post-operatively. Minor complications were common, but there were no revisions and no cases with radiographic loosening. There was no correlation between bushing wear and the DASH or MEPS.

Conclusion

Incidence of bushing wear in total elbow arthroplasty is high, and under-diagnosed without stress views. Although minor complications are common, frequent loosening and revision do not occur as previously reported for other implants. Despite bushing wear, mid-term functional outcomes are good.

Level of Evidence

Therapeutic IV.

Introduction

Total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) for the treatment of post-traumatic conditions has historically been considered a salvage procedure due to unfavorable outcomes and frequent complications1,2. Complications have included infection, ulnar neuropathy, triceps insufficiency, implant fracture, periprosthetic fracture, aseptic loosening, and bushing wear1,8.

Bushing wear is a common reported concern for current TEA designs, however the true incidence is difficult to determine due to lack of consistency in the way it is defined and measured. For the Coonrad-Moorey implant, which is designed to have 7 degrees of ulno-humeral laxity, definitions of bushing wear have ranged from qualitative descriptions, such as “asymmetric tilt of the implant,” to specific grades of severity based on quantitative measurements1,2. Wright et al recommended that bushing wear be measured on anteroposterior (AP) stress radiographs, with the elbow stressed from full varus to full valgus; if the entire arc measured 7–10 degrees, then the bushings were considered partially worn and if greater than 10 degrees, then believed to be completely worn10. Unfortunately, most studies do not include stress views of the elbow and therefore the actual incidence of bushing wear is unknown9,11.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the incidence of bushing wear utilizing stress radiographs in patients treated with total elbow arthroplasty for a post-traumatic condition. We also report correlation between bushing wear and clinical outcome.

Materials and Methods

Following institutional review board approval, a retrospective chart and radiographic review was performed for patients who underwent total elbow arthroplasty for post-traumatic arthritis (PTA) or nonunion from 1997–2009 by a single surgeon. Patients who qualified for the study were contacted by phone to return for a clinical and radiographic evaluation. Further effort to locate patients who were not found through the hospital database was done using the website http://www.intelius.com and the Social Security Death index. Inclusion criterion was primary total elbow arthroplasty for PTA or nonunion with stress radiograph follow-up of at least 2 years. Patients who had a prior resection arthroplasty were also included. Exclusion criteria included acute elbow trauma less than 3 months prior to TEA, revision arthroplasty involving only 1 component, inflammatory or primary osteoarthritis, and malignancy about the elbow.

There were a total of 66 patients (75 elbows) who underwent primary or revision total elbow arthroplasty from 1997–2009, of which 18 elbows in 18 patients were for PTA or nonunion. Eight patients met inclusion criteria with an average follow-up of 105 months (range 33–173 months). There were 6 women and 2 men with an average age of 67 years (range, 53–74 years) at the time of the operation. Six patients were older than 65 years. PTA was the primary diagnosis in 2 patients and nonunion in 6 patients. Four patients had undergone previous surgeries for open reduction internal fixation or external fixation while three were primary arthroplasties. One patient had a reimplant after a resection arthroplasty for infection. Hardware placed for fracture fixation was removed in 3 elbows at the time of surgery. The dominant extremity was involved in 38% of the cases.

A single surgeon performed all the surgeries using the third generation Coonrad-Moorey (Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana) semi-constrained linked implant system. The technique included triceps reflection and ulnar nerve transposition, if not previously transposed. Antibiotic-impregnated polymethylmethacrylate was used for fixation. Standard closure along with a subcutaneous drain and posterior slab splint was used. The patient was maintained on intravenous antibiotics for 24 hours post-operatively.

Radiographic evaluation

A musculoskeletal radiologist reviewed radiographs. Pre-operative radiographs were available for review in 4 elbows, while the others had been destroyed. All eight elbows had complete post-operative radiographic evaluations (anteroposterior [AP], lateral, and varus-valgus stress views). The standard AP view was taken with the elbow in maximum extension, and the lateral view with the elbow flexed to 90°. The AP stress views were obtained in maximum extension possible while stabilizing the humerus with 1 hand and applying maximum tolerable valgus or varus force to the forearm with the other hand. All stress radiographs were performed by one of the authors. Bushing wear was measured on both the AP view without applied stress and the AP varus-valgus stress views by a radiologist as previously described by Ramsey et al11. In this method, a line parallel is drawn parallel to the humeral yoke, and another line is drawn parallel to the medial or lateral edge of the ulnar component's articular surface. A joint angle >10° on any single AP view indicates excessive tolerance of the bushings due to wear or plastic deformation, while angle >7–10° suggests mild to moderate wear, and ≤7° is considered normal.

Implant loosening was graded on AP and lateral radiographs according to the classification described by Morrey12. In this classification, radiolucency is graded as Type 0 if a radiolucent line is less than one millimeter wide and involving less than 50% of the interface, Type I if a radiolucent line is at least 1 millimeter wide and involving less than 50% of the interface, Type II if a radiolucent line is more than 1 millimeter wide and involving more than 50% of the interface, Type III if a radiolucent line is more than 2 millimeters wide and around the entire interface, and Type IV if there is gross loosening.

Clinical evaluation and chart review

Outcome measures included the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire, Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS), patient satisfaction questionnaire, range of motion, and complications.

The DASH measures pain and function and is based on a 0 to 100 scale, with 0 indicating the best score. The MEPS has a maximum score of 45 points for pain, 25 points for daily functional activities, 20 points for motion, and 10 points for stability. An excellent outcome is defined as a score ≥90 points, good if between 75 and 89 points, fair if between 60 and 74 points, and poor if <60 points. The MEPS data were only collected postoperatively at the follow up for this study. The patient satisfaction score was based on a one-to-five Likert scale, with 1 indicating most satisfied.

Range of motion was measured using a goniometer. Complications were obtained from chart review and were divided into minor and major.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student's t-test with 2-tailed distribution for clinical and radiographic parameters. Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated to assess correlations between bushing wear and questionnaire scores. Level of significance was set at less than 0.05.

Results

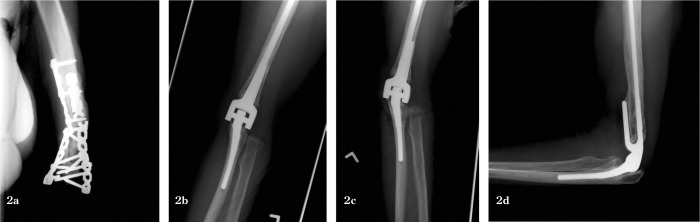

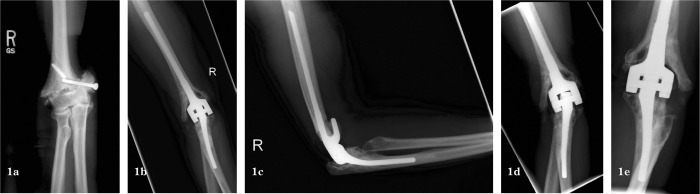

Average joint angle was 5.6° without stress compared to 13.6° of total arc on the stress view (p=0.002) (Table 1). Joint angulation greater than 10° of total arc was noted in 5 out of 8 (63%) elbows, compared to 1 out of 8 (12.5%) elbows on the non-stress AP view (Figures 1, 2). Therefore, absolute bushing wear was detected 5 times more frequently with stress views than without. There was greater joint angulation with valgus (9.9°) versus varus stress (3.8°) (p=0.002). There was no correlation between bushing wear and DASH (R2=0.008, p=0.83) or MEPS (R2=0.04, p=0.63).

Table 1.

Postoperative radiographic evaluation

| Diagnosis | Age/Sex | X-ray follow-up (months) | Bushing angle (degrees) | Radiolucency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | Varus stress | Valgus stress | Varus-valgus arc | |||||

| 1 | Nonunion | 59F | 173 | 6 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 1 |

| 2 | Nonunion | 70F | 78 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 15 | 1 |

| 3 | Nonunion | 66F | 127 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 1 |

| 4 | Nonunion | 70M | 68 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| 5 | Nonunion | 73F | 103 | 12 | 12 | 16 | 28 | 0 |

| 6 | PTA | 53F | 138 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 16 | 1 |

| 7 | PTA | 74M | 124 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 1 |

| 8 | Nonunion | 70F | 33 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 1 |

| Average | 105 | 5.6 | 3.8 | 9.9 | 13.6 | |||

Figure 1. A 59-year-old female with distal humerus nonunion and hardware failure underwent total elbow arthroplasty. There was significant bushing wear and stable type I osteolysis at 14.4 years, a) pre-operative AP, b) AP, c) lateral, d) valgus stress, e) varus stress at 14.4 years.

Figure 2. A 66-year-old female with distal humerus nonunion underwent total elbow arthroplasty. Postoperative radiographs show moderate bushing wear and Type I osteolysis at 10.6 years, a) preoperative AP; b) post-operative AP, c) valgus stress, d) and lateral view at 10.6 years.

Seven elbows had type I, and one elbow had type 0 radiolucency changes (Figures 1, 2). All radiolucency changes were limited to the periarticular region, with none surrounding the stems of the implant (Table 1).

Clinical data

DASH score improved from 70 pre-operatively to 28 post-operatively (p=0.20) (Table 2). The mean MEPS was 85, with 75% having good to excellent results. Mean patient satisfaction score was 2 out of 5.

Table 2.

Pre- and postoperative range of motion and questionnaire results

| Range of Motion* | Questionnaires+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | Extension | Supination | Pronation | DASH | MEPS∧ | |

| Pre-operative | 128±14 | 29±25 | 56±49 | 71±24 | 70±19 | |

| Post-operative | 129±7 | 27±26 | 69±40 | 77±15 | 28±30 | 85±21 |

Values are given as the pre- and postoperative mean and standard deviation, in degrees.

Values are given as the pre- and postoperative mean and standard deviation, except for MEPS.

Post-operative score.

Mean flexion–extension arc of motion was overall unchanged from 99° (range, 50–145°) pre-operatively to 103° (range, 46–120°) postoperatively (p=0.99) (Table 2). Mean pronosupination arc improved from 127° (range, 40–170°) pre-operatively to 146° (50–170°) postoperatively (p=0.22).

Complications

There were 4 minor complications in 3 patients, which included a stitch abscess, recurrent olecranon bursitis, hematoma requiring intravenous antibiotics, and ulnar neuropathy that had worsened from pre-operatively. Two of the 3 patients with complications had had prior surgery. The patient with a stitch abscess was treated with suture removal, and the olecranon bursitis was treated with IV and oral antibiotics and a compressive bandage with resolution at 1-year follow-up. The patient who had an exacerbation of his pre-existing ulnar neuropathy had improved symptoms at his most recent follow-up. There were no major complications and no deep infections. None of the patients had implant revision surgery.

Discussion

The Coonrad-Moorey total elbow arthroplasty is a semi-constrained, linked implant with a hinged design that is claimed to reduce force at the prosthesis-bone interface. The implant has an important role in reconstruction for elbow conditions characterized by deformity, bone loss, and instability, with good patient satisfaction and functional scores6,14,15. Bushing wear, however, is a known complication at mid-term to long-term follow-up, particularly in patients with post-traumatic arthritis1,2. Incidence of bushing wear is variable, and may be underdiagnosed in the absence of stress views.

Our study demonstrates that stress views are much more sensitive for detecting bushing wear compared to a standard AP view. This suggests that bushing wear may be under-reported in the literature, as most total elbow arthroplasty studies do not evaluate stress radiographs. Of note, we specifically limited our study to include only patients treated for a posttraumatic condition. Despite the high rate of bushing wear, none of the patients in our study required a bushing exchange or revision surgery. There was also no correlation with clinical or functional outcome. This finding appears to be consistent with what is reported in the literature

Throckmorton et al reported a 34% rate of bushing wear at 9-year follow-up of 69 patients with PTA2. This was a radiographic finding in 41% of the cases and was treated conservatively. Bushing wear rate in another study by Cil et al was 37%, with one of 32 elbows requiring isolated bushing exchange1. Lee et al at reported a 1.3% bushing exchange rate in 919 primary total elbow replacements at an average of 7.9 years. Indications for surgery were pain, crepitus, or squeaking but with a well-fixed implant by radiographic assessment9. They did not state what percentage of patients had asymptomatic bushing wear, but did acknowledge that the absence of stress radiographs was a weakness of their study. At surgery for bushing exchange, no extensive osteolysis was found and all implants were well fixed. They concluded that when there was radiographic evidence of bushing wear but no symptoms, the patient should be offered surgery only if pain or mechanical squeaking develops9.

On the other hand, Wright et al reviewed 10 patients who underwent bushing exchange and found that all patients had obvious osteolysis and metallic synovitis. They stated that particulate polyethylene and metal debris generated from bushing wear was common, and recommended early bushing exchange and synovectomy for patients with synovitis, bushing wear, or osteolysis10. Findings from a retrieval study of 16 Coonrad-Moorey implants revised for pain, crepitus, implant fracture, or a grossly loose prosthesis, suggest that polyethylene deformation or wear could lead to metal-on-metal contact between the humeral and ulnar components resulting in osteolysis18. So, although our study and several others suggest that asymptomatic bushing wear can be treated conservatively, there is evidence to support more aggressive intervention. Stress radiographs in this situation may assist the surgeon in making a decision on whether bushing exchange would be helpful.

We do acknowledge that obtaining stress views can be challenging, especially in patients with a flexion contracture. We only applied maximum tolerated varus and valgus stress with the elbow in as much extension as possible to minimize patient discomfort. We suspect that the degree of flexion contracture may affect the ulnohumeral angle measurement.

Clinical outcomes in our small cohort were also consistent with what is reported in the literature, with an average MEPS of 85 at our 8-year follow-up. Average MEPS for a group of patients treated for non-union at 6.5 years was 811. Throckmorton et al reported average MEPS of 75 at 9-year follow-up of patients with PTA2.

Our overall 38% complication rate was higher than in many previous studies, however all complications were minor. Two of three patients with complications had previous surgery, which is a known risk factor1. One patient had worsening of his ulnar neuropathy. Ulnar neuropathy has been reported to be as high as 26%, with permanent injury ranging from 0 to 10%3. Wound and soft tissue problems have reported to range up to 13%1,2. There were no deep infections in our cohort, although in the literature, rates range from 0 to 10%3,4,12,15,16.

None of the patients in our cohort required a revision or explant. This may in part reflect an improved implant design introduced in 1981 that was used in our patients17. In 1994, Kraay et al reported results of a linked semi-constrained arthroplasty for patients with non-union or PTA, and found a survival rate of 73% at 3 years and 53% at 5 years, which was worse than the rates found for their patients with inflammatory arthritis (92% and 90%, respectively)4. Cil et al reported results of TEA for nonunion, and at average 6.5 years, 23 of 92 elbows underwent revision or removal, resulting in a prosthetic survival of 82% at five years and 65% at 10 and 15 years1. Complications included aseptic loosening, fractured components, and periprosthetic fractures, and occurred while using an implant design that had a pre-coated ulnar component and a c-ring locking mechanism. Ensuing design changes included a plasma-sprayed ulnar component and snap-fit articulation. Risk factors for implant failure were patient age less than 65 years, 2 or more prior surgical procedures, and a history of infection. Throckmorton et al reported 19% failure rate in 84 patients after linked semi-constrained TEA for posttraumatic conditions2. Their incidence of loosening was 19%, with 25% of those cases being grossly loose. Survival rate was 92% at 5 years, 78% at 10 years, and 70% at 15 years. They also noted that 75% of the failures were in patients less than 60 years old at the time of index TEA2. The majority of patients in our study were older than 65 years, which may have contributed to our better results.

The major weakness of our paper was the small cohort size. However, this is the first study to compare non-stress versus stress radiographs of total elbow arthroplasty, with clinically important findings.

In summary, stress views of the elbow are more sensitive in diagnosing radiographic bushing wear compared to non-stress views. Despite the high incidence of bushing wear, we did not detect any clinical correlation nor have complications related to bushing wear at 8-year follow-up in patients treated with a post-traumatic condition. Stress radiographs are relatively cheap and non-invasive and should be considered in evaluating bushing wear.

References

- 1.Cil A, Veillette CJ, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey BF. Linked elbow replacement: a salvage procedure for distal humeral nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Sep 2008;90(9):1939–1950. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Throckmorton T, Zarkadas P, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey B. Failure patterns after linked semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for posttraumatic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jun 2010;92(6):1432–1441. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hildebrand KA, Patterson SD, Regan WD, MacDermid JC, King GJ. Functional outcome of semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Oct 2000;82-A(10):1379–1386. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraay MJ, Figgie MP, Inglis AE, Wolfe SW, Ranawat CS. Primary semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. Survival analysis of 113 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Jul 1994;76(4):636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Results after 562 total elbow replacements: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. May–Jun 2009;18(3):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrey BF, Schneeberger AG. Total elbow arthroplasty for posttraumatic arthrosis. Instructional course lectures. 2009;58:495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inglis AE, Pellicci PM. Total elbow replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Dec 1980;62(8):1252–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneeberger AG, Adams R, Morrey BF. Semiconstrained total elbow replacement for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Aug 1997;79(8):1211–1222. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199708000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee BP, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Polyethylene wear after total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. May 2005;87(5):1080–1087. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright TW, Hastings H. Total elbow arthroplasty failure due to overuse, C-ring failure, and/or bushing wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. Jan–Feb 2005;14(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey ML, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Instability of the elbow treated with semiconstrained total elbow arttvcorAasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jan 1999;81(1):38–47. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrey BF, Bryan RS, Dobyns JH, Iinscheid RL. Total elbow arthroplasty. A five-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Sep 1981;63(7):1050–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moro JK, King GJ. Total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of posttraumatic conditions of the elbow. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. Jan 2000;(370):102–114. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200001000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Driscoll SW, An KN, Korinek S, Morrey BF. Kinematics of semi-constrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bowe Joint Surg Br. Mar 1992;74(2):297–299. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B2.1544973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrey BF, Adams RA. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Jan 1995;77(1):67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aldridge 3rd JM, Iightdale NR, Mallon WJ, Coonrad RW. Total elbow arthroplasty with the Coonrad/Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis. A 10- to 31-year survival analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Apr 2006;88(4):509–514. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.17095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrey BF, Adams RA, Bryan RS. Total replacement for post-traumatic arthritis of the elhow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Jul 1991;73(4):607–612. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg SH, Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, King GJ, O'Driscoll SW, Cohen MS. Modes of wear after semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Mar 2008;90(3):609–619. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]