Breast cancer rates are increasing in low- and middle-income countries, with high case fatality rates, in part because of delayed diagnosis and treatment. The delays experienced by patients with breast cancer at two rural Rwandan cancer facilities were investigated. Longer delays were associated with more advanced-stage disease. An opportunity exists to reduce breast cancer mortality in Rwanda by addressing barriers in the community and healthcare system to promote earlier detection.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Delays, Africa, Rwanda, Early detection

Abstract

Background.

Breast cancer incidence is increasing in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Mortality/incidence ratios in LMICs are higher than in high-income countries, likely at least in part because of delayed diagnoses leading to advanced-stage presentations. In the present study, we investigated the magnitude, impact of, and risk factors for, patient and system delays in breast cancer diagnosis in Rwanda.

Materials and Methods.

We interviewed patients with breast complaints at two rural Rwandan hospitals providing cancer care and reviewed their medical records to determine the diagnosis, diagnosis date, and breast cancer stage.

Results.

A total of 144 patients were included in our analysis. Median total delay was 15 months, and median patient and system delays were both 5 months. In multivariate analyses, patient and system delays of ≥6 months were significantly associated with more advanced-stage disease. Adjusting for other social, demographic, and clinical characteristics, a low level of education and seeing a traditional healer first were significantly associated with a longer patient delay. Having made ≥5 health facility visits before the diagnosis was significantly associated with a longer system delay. However, being from the same district as one of the two hospitals was associated with a decreased likelihood of system delay.

Conclusion.

Patients with breast cancer in Rwanda experience long patient and system delays before diagnosis; these delays increase the likelihood of more advanced-stage presentations. Educating communities and healthcare providers about breast cancer and facilitating expedited referrals could potentially reduce delays and hence mortality from breast cancer in Rwanda and similar settings.

Implications for Practice:

Breast cancer rates are increasing in low- and middle-income countries, and case fatality rates are high, in part because of delayed diagnosis and treatment. This study examined the delays experienced by patients with breast cancer at two rural Rwandan cancer facilities. Both patient delays (the interval between symptom development and the patient’s first presentation to a healthcare provider) and system delays (the interval between the first presentation and diagnosis) were long. The total delays were the longest reported in published studies. Longer delays were associated with more advanced-stage disease. These findings suggest that an opportunity exists to reduce breast cancer mortality in Rwanda by addressing barriers in the community and healthcare system to promote earlier detection.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide. Breast cancer incidence in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is lower than that in high-income countries but is increasing rapidly [1]. The breast cancer mortality/incidence ratios in LMICs are markedly higher than those in high-income countries [1], likely in part because of the limited human and financial resources for effective treatment and advanced-stage presentations, which limit treatments' benefit [2–5]. Along with increasing access to affordable, effective treatment, promotion of earlier stage presentations in LMICs is urgently needed [4].

Delayed breast cancer diagnoses are likely a major contributor to advanced-stage presentations in LMICs [5]. The research data have generally divided diagnostic delays into “patient delay” (the delay between a patient’s onset of symptoms and first seeking care at a healthcare facility) and “system delay” or “provider delay” (the delay between the first presentation to a healthcare provider and diagnosis [or treatment initiation, depending on the study]) [5]. Studies from high-income countries have suggested that patient delay is linked to advanced-stage presentations and worse survival [6, 7]. Less evidence is available from high-income countries associating system delays with advanced-stage disease [6, 8].

Experts have called for research on breast cancer delays in LMICs to guide early detection interventions tailored to the needs and contexts of the individual countries [4, 9]. Although the body of evidence from LMICs is increasing [7], the data quality has been mixed. Many of the existing studies are limited by unclear definitions of delay and methods for determining lengths of delay [5, 10, 11] or did not control for confounding when examining risk factors for delay or associations between delay and disease stage [10, 12]. Additionally, very few studies have been from countries designated as low income [13] (as opposed to middle income). Because low-income countries could have dramatically different health resources and systems, this is an important gap in the published data. Historically, more studies have examined patient delay [2, 5, 7, 12, 14, 15], and interest is now growing in examining system delay, which is likely to be significant and offer important opportunities for intervention in settings with limited primary care infrastructure [10, 11, 16–19]. To our knowledge, none of the published reports from low-income countries have quantified system delays from first presentation or examined the association between system delays and disease stage.

In the present study, we assessed the patient and system delays in breast cancer diagnosis in Rwanda, a small, population-dense country of 10.5 million in East Africa, designated as low income by the World Bank. Rwanda has achieved dramatic improvements in health indicators since its 1994 genocide, including a doubling of life expectancy [20], and the nation is now embarking on an ambitious national plan to address noncommunicable diseases, including cancer [21–23]. Of Rwanda’s population, 81% lives in rural areas and accesses healthcare through community healthcare workers and rural health centers staffed by nurses [20, 22].

Before 2012, cancer care in Rwanda was very limited. Only 2 oncologists were in the country, access to surgeons with oncologic expertise was limited, and no in-country radiotherapy facility was available. Capacity for pathological examination for diagnosis was very limited, and select cancer therapies were available only on a small scale to patients with the means to afford it at Rwanda’s two main teaching hospitals and a semiprivate hospital in Kigali [22]. Chemotherapy was also provided free of charge to a small number of patients at Rwinkwavu Hospital, a rural district hospital in the eastern province, through a partnership between the Ministry of Health (MOH) and the nongovernmental organization Partners in Health (PIH). In July 2012, with financial and technical support from PIH, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and other key partners, the MOH opened a national cancer referral center at another rural district hospital, Butaro Hospital. The Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence has a dedicated cancer clinic, ward, pathology laboratory, staff trained in cancer care, and cancer protocols developed in partnership with U.S. oncologists [23, 24]. Butaro currently serves the largest volume of cancer patients in the country, like Rwinkwavu providing cancer care free of charge to patients from all over Rwanda, including the rural poor [22]. Breast cancer is the most common cancer among adults at Butaro Hospital [23].

The objectives of our project were to quantify the length of both patient and system delays experienced by patients with confirmed breast cancer at Butaro and Rwinkwavu, to assess the sociodemographic and clinical risk factors for delay, and to determine whether longer patient and system delays were related to advanced-stage disease at diagnosis after adjustment for other factors. We hypothesized that system delays would be as long, if not longer, than patient delays and that longer delays would be associated with late-stage disease. Our ultimate goal was to inform a national early detection intervention to promote earlier detection of breast cancer in Rwanda. In addition, we sought to add to the published data concerning patient and system delays in low-income countries and, in particular, to further elucidate the relationship between patient and system delays and breast cancer stage in such settings.

Materials and Methods

Patients

From November 2012 to February 2014, we surveyed women aged ≥21 years who were presenting with a breast complaint and abnormal breast examination findings to the twice-weekly oncology clinics at Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospitals. Women could participate at their first visit or their visit to receive biopsy results, if trained study staff were available. In the present analysis, we included only patients with pathologically confirmed breast cancer. Some patients had been referred to Butaro or Rwinkwavu after a cancer diagnosis at another facility. These patients were only included in the present analysis if their initial stage was documented in our medical records or if their initial stage was unavailable but the initial diagnosis was made no more than 6 months prior to staging at our facilities. Patient recruitment and eligibility for the present analysis are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients included in our analysis.

Data Collection

We adapted an instrument developed by researchers in Haiti [25] to the Rwandan context and objectives. The questionnaire gathered demographic and clinical information and information regarding women’s experiences with their breast problem, including the dates of the initial symptoms and first healthcare facility presentation. We also asked patients which factors, from two lists, were the reasons for the delay. The questionnaire was translated into Kinyarwanda and back-translated into English. It was piloted with clinical staff members and underwent cognitive testing with 5 patients and subsequent revision. The questionnaire was administered verbally in Kinyarwanda by a trained study staff member in a private room. A copy of the instrument is available from the authors. We reviewed medical records to determine the breast cancer diagnosis, diagnosis dates, and American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th edition (AJCC) breast cancer stage [26], determined using clinical and pathologic information.

Key Variables

Patient delay was defined as the number of months between breast symptom onset and the patient’s first presentation to a doctor or nurse. System delay was defined as the number of months between the first visit to a doctor or nurse and the date of the first pathology report confirming breast cancer. When patients were unable to provide a date for when their symptoms began or the first provider visit, they were asked to provide a month or month range and year. If they provided a month, the date was estimated as the 15th of that month; if they provided a month range, the estimated date was the midpoint between the 15th of those months. If patients were only able to provide a year, the estimated date was June 30th of that year.

At Butaro and Rwinkwavu Hospitals, breast cancer was staged using both the AJCC staging system and a simplified system of “early,” “locally advanced,” and “metastatic,” corresponding to AJCC stages I and II, stage III, and stage IV, respectively. During the early phases of the cancer program, the simplified staging was the most frequently available; thus, we used the simplified strategy to define stage I/II, stage III, and stage IV patients.

The key independent variables included demographic information and features of the patients’ experiences with a breast problem, such as their knowledge about breast cancer, type of healthcare provider seen first, and number of healthcare facility visits before the diagnosis. Healthcare facility visits were dichotomized as <5 or ≥5 (owing to the phrasing of the survey question, some patients with 5 visits might have been categorized as having <5). HIV status was extracted from the medical record and was determined from the laboratory results at the clinical intake visit. If the results were not available, we relied on patient self-report, because the HIV status was routinely queried during the clinical intake interview. Other comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, hepatitis, heart failure, or “other” health problems, were identified through self-report at the same visit. The categorization of the variables is listed in Table 1.

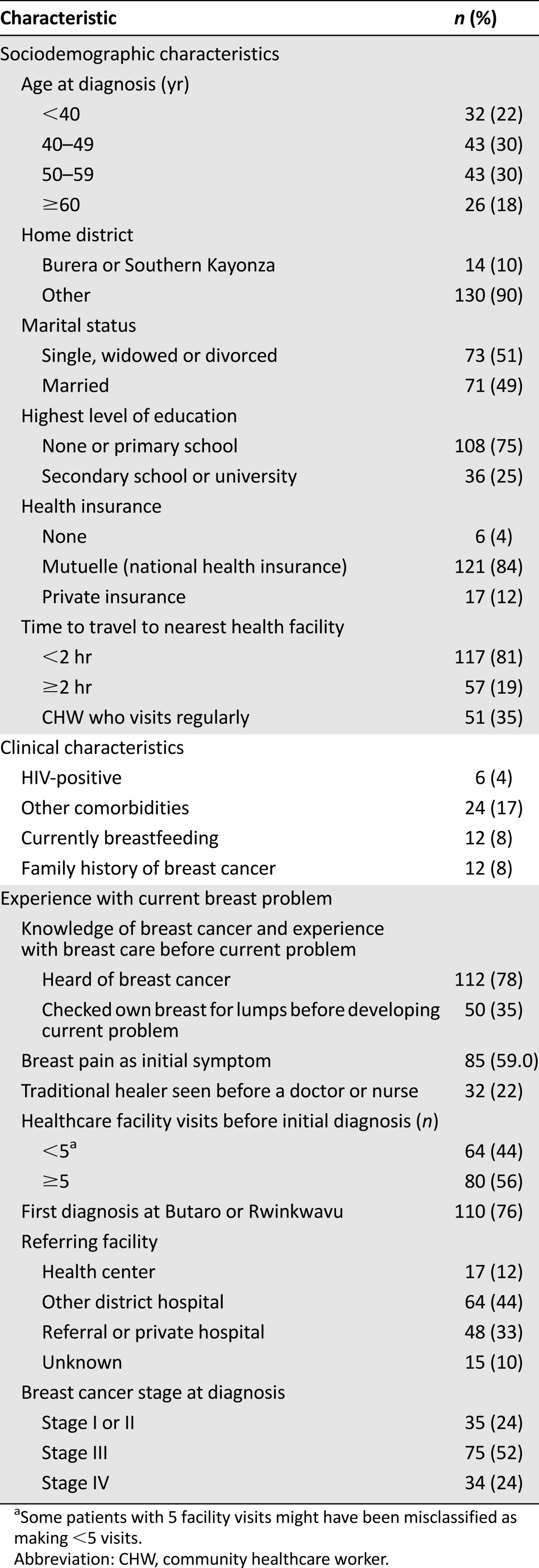

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 144)

Statistical Analysis

After describing patient characteristics, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare the lengths of patient, system, and total delay among patients with stage I/II, III, or IV disease at diagnosis. We performed multivariate logistic regression analysis to analyze the association of longer patient and system delays with stage, adjusting for clinical and demographic characteristics. Chi-square tests and multivariate logistic regression analysis were performed to assess the factors associated with longer delays. Because of the threshold effect noted in our analyses of the relationship between delay and stage (Fig. 2), we used delays of ≥6 months to define long delays in the subsequent analyses, although we also performed sensitivity analyses categorizing delay into quartiles and categorizing patient delay as <3 or ≥3 months, as was done in other studies [5]. In these logistic regression models, we included all variables plausibly related to a longer patient delay or system delay. We then removed the variables, including insurance type and facility where breast cancer was first diagnosed, that correlated highly with another variable in the model. Two-sided p values <.05 were considered statistically significant. We also performed sensitivity analyses eliminating patients who had provided only a year for the date of symptom onset or first provider visit. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Systems, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, http://www.sas.com).

Figure 2.

Multivariate ordinal logistic regression model examining the relationship of patient and provider delay and more advanced-stage disease (stage I/II vs. III vs. IV), adjusting for demographic and clinical factors.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Ethics

All participants provided informed consent. The Rwanda National Ethics Committee, Rwanda Ministry of Health, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital institutional review board provided ethical approval.

Results

The questionnaire response rate was 99%. Of the 159 patients with breast cancer interviewed, 144 were included in the present analysis (Fig. 1). From a medical record review conducted at Butaro Hospital, we estimated that the cancer patients interviewed represented approximately 80% of new breast cancer patients presenting to the two hospitals during the study period. The cohort characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median patient age was 49 years. Most patients had no or primary education and most had national public insurance at their interview. Of the 144 patients, 76% had their first diagnosis of breast cancer at Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospital and 33% had been referred to Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospital by a private or referral hospital. Also, 52% of the women had stage III disease and 24% had stage IV disease at diagnosis. When asked when their symptoms began, 11% provided the full date, 58% provided the month and year, 5% provided a month range and year, and 26% provided only the year. For the date of the first healthcare visit, 44% provided the full date, 47% provided the month and year, 1% provided a month range and year, and 8% provided only the year.

Delay and Stage at Diagnosis

The delays experienced by patients overall and stratified by stage are presented in Table 2. Overall, the median total delay was 15 months; median delays were 11, 13, and 24 months among patients with stage I/II, III, and IV disease, respectively (p = .001). The median patient delay was 5 months (2, 5, and 9 months for patients with early, locally advanced, and metastatic disease; p = .09). The median system delay was 5 months (range, 4–11 months when stratified by stage; p = .005). In multivariate models adjusting for clinical and demographic characteristics, when compared with delays of <3 months, both patient and system delays of ≥6–12 months and delays of ≥12 months increased the odds of more advanced-stage disease (overall p = .006 for patient delay; p = .01 for provider delay; Fig. 2). When the patients who provided only the year of either symptom onset or first provider visit were excluded, the results were similar.

Table 2.

Patient, system, and total delays by stage at diagnosis

Factors Associated With Patient and System Delays

In the adjusted analyses, low education was the only demographic or socioeconomic factor significantly associated with a patient delay of ≥6 months (odds ratio [OR], 4.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.72–13.88; p = .003; Table 3). Patients who saw a traditional healer before a nurse or doctor were also significantly more likely to have delayed presentations (OR, 4.26; 95% CI, 1.56–11.60; p = .005). These findings were similar when we used a patient delay of ≥3 months as the outcome variable.

Table 3.

Factors associated with patient and system delays

In the adjusted analyses assessing system delays, patients who visited other healthcare facilities ≥5 times before diagnosis were more likely to experience system delays of ≥6 months (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.24–5.84; p = .01; Table 3). Patients residing in Butaro’s or Rwinkwavu’s district were less likely to experience long system delays (OR, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.004–0.55; p = .02).

Barriers to Seeking and Obtaining Care

When patients were asked why they did not go to a healthcare facility sooner, the two most common reasons were not being bothered initially by the problem and thinking it would go away (Table 4). The two most common reasons for a delayed presentation to Butaro or Rwinkwavu for diagnosis were delayed referral and not knowing about the cancer center. The inclusion of these variables in the regression models assessing longer delays did not demonstrate any associations between the reasons and the length of delays nor did it change the associations described in the previous section. In sensitivity analyses excluding patients who provided only the year for the date of the first facility visit or first provider seen, all results were similar (data not presented).

Table 4.

Reasons for delay

Discussion

Breast cancer patients presenting to two rural cancer referral hospitals in Rwanda experienced very long delays between the onset of breast symptoms and definitive diagnosis. Patient and system delays were equally long, and both were significantly associated with more advanced-stage cancer in adjusted analyses. The present study is one of only a few to demonstrate an association between longer system delays and advanced-stage disease in LMICs, and the first of which we are aware to do so in a low-income country. To our knowledge, the total delays reported by our patients are the longest reported, with the potential exception of an Ethiopian study, which reported a mean patient delay of 18 months but did not report the median delay [5, 27]. Our findings are consistent with a small medical record review study at one of Rwanda’s teaching hospitals, which relied on information reported in 33 medical records to suggest that 85% of patients waited longer than 3 months before seeking care [28], and a recent population-based survey assessing untreated surgical disease in Rwanda and Sierra Leone. Of 79 Rwandan women with a self-reported breast mass, 89% had had the mass for more than 12 months; reportedly, most women had not yet sought medical evaluation [29]. Our findings suggest that as low-income countries’ capacity to treat cancer expands, efforts to promote earlier detection of symptomatic disease could have a substantial impact on disease stage and curability. These efforts should target communities and healthcare providers and systems to address patient and system delays.

Our study suggests some reasons for both patient and system delays in our study population. We found that a low educational level was significantly associated with patient delay, consistent with some other studies performed in LMICs [7, 12]. Supporting the role of limited breast cancer knowledge, not being bothered by a breast problem or thinking that it would go away were the most commonly cited reasons that patients did not seek care sooner. These perceptions are risk factors for delay worldwide [7]. Although all patients in Rwanda have access to a community healthcare worker (CHW) and Rwandan CHWs play a vital role in healthcare delivery and outcomes [30], no patients in our study reported discussing breast symptoms with a CHW. This suggests an opportunity to involve CHWs in raising breast cancer awareness and encouraging women to present earlier with breast symptoms [31]. Just as in several middle-income countries, seeking care from traditional practitioners was associated with an increased likelihood of a delayed presentation [10, 18, 19, 32]; thus, involving traditional healers in educational activities should be considered. In contrast to some studies [8, 12, 29, 33, 34], a lack of pain, patient age, a positive family history, the distance from a patient's home to a healthcare facility, and marital status were not significantly associated with patient delays in our study.

Factors significantly associated with longer system delays included 5 or more visits to healthcare facilities before arriving at Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospital, an experience shared by 56% of the patients. Most Rwandan patients go first to health centers (rural facilities staffed by nurses with secondary school education); to receive public insurance coverage for care provided at a district hospital, referral from a health center is needed. For patients from outside Butaro’s and Rwinkwavu’s districts, formal referral from their district hospital or a higher level healthcare facility is necessary to receive coverage for cancer care at Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospital. Many patients described the need for a referral as a reason for delay. This could have been because of the need for the additional visit or because the providers initially seen did not recognize the warning signs of cancer or did not know where to refer the patient and thus did not provide the referral promptly. Living within Butaro’s and Rwinkwavu’s districts was associated with a shorter delay between the initial presentation and the diagnosis. This has several potential explanations. First, patients from those two districts can go directly from a health center to Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospital, without the need to visit another hospital, although they do need a referral from the outpatient (noncancer) department at Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospital. Additionally, it is likely that health center nurses in those districts were more familiar with the cancer diagnostic and treatment resources available at their district hospital and might have made referrals to the hospitals more promptly. The shorter distance to the hospital could also have contributed to less system delay, although only 2 patients in our study reported travel distance as a reason for a longer time to presentation at the two hospitals. However, because geographic proximity to a referral center has been associated with cancer stage in other settings [34], additional analysis of the effect of geography on delays could be useful in guiding the expansion of cancer services in Rwanda.

Our study had several limitations. First, delays were reported by patients, who might have underreported patient delay because of social desirability concerns [35]. Second, many patients could not precisely specify a date when their symptoms began. Although patients whose symptoms began longer ago might have been less able to provide precise information, we would not expect our estimation strategy to bias our results in a particular direction. Additionally, sensitivity analyses confirmed that our findings remained consistent when we excluded those patients who provided only the year for symptom onset or first facility visit. Third, it is likely that we did not assess all the important contributors to delay. Because we relied on patient interviews and hospital medical records and did not obtain details regarding patients’ pathways through the healthcare system, our assessment of healthcare system-related factors, including events at healthcare centers and other referral facilities, was particularly incomplete. In addition, we had limited power to detect small differences in patient or system factors that might have been associated with delays.

Finally, patients with breast cancer presenting to Butaro and Rwinkwavu Hospital might not be representative of all patients with breast cancer in Rwanda. Rwanda does not yet have a national cancer registry, and the existing estimates of cancer and breast cancer incidence are based on very limited regional data [36]. The number of cancer patients presenting to other Rwandan hospitals is unknown. However, Butaro Hospital (where 94% of our patients received care) appears to serve the highest volume of breast cancer patients nationally. For example, 190 breast cancer patients were seen from July 1, 2012 to June 30, 2013 at Butaro [23]. A medical record review of all three of Rwanda’s national referral hospitals from 2007 to 2011 revealed only 145 patients for that entire period [28]. There do appear to be some differences between our study population and the population of Rwanda as a whole. For example, our study population had lower levels of education but higher rates of private insurance [37]. The hospitals’ own rural districts were overrepresented in our study population; however, Kigali city was also overrepresented (19% of our study population vs. 11% of the country’s population in 2012) [38]. Some breast cancer patients who seek care at private or other referral facilities or outside of Rwanda might never present to Butaro or Rwinkwavu Hospital, and one might hypothesize that these patients might have better access to care and thus experience shorter delays than those in our study. However, 33% of our patients were referred to Butaro or Rwinkwavu by private or referral facilities. Also, although one half of those patients had diagnoses made at the referral facility, they appeared to have experienced equally long system delays in the adjusted analyses. Finally, patients with breast cancer who never reach a medical facility for a formal diagnosis were not represented in the present study. Overall, however, in particular, because Butaro’s and Rwinkwavu’s services are available through the public system and to the rural poor, we believe that our study results offer insight into the experiences of many of the patients seeking care at the start of Rwanda’s cancer initiatives.

Conclusion

Patients with breast cancer presenting to two rural cancer referral facilities in Rwanda described diagnostic delays that are the longest reported in published studies. Both patient and system delays were associated with advanced-stage presentations. Our findings suggest potential opportunities to improve outcomes from breast cancer in Rwanda as it pursues its broad national strategy to combat noncommunicable diseases. Along with continued efforts to build nationwide capacity for cancer care, awareness campaigns teaching communities, CHWs, and traditional healers about breast cancer’s signs, symptoms, and potential curability when detected early could reduce patient delay. In addition, educating primary healthcare providers about breast cancer, the importance of timely referrals, and where to refer patients for diagnostic services could reduce system delay. Streamlining referrals to a cancer center could be explored for patients in whom cancer is suspected. As Rwanda implements a national cancer control strategy, additional research should examine the effect of early detection programs and expanding cancer resources and capacity on diagnostic delay and cancer stage.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Pace's work was supported by the Global Women’s Health Fellowship, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Keating is supported by K24CA181510 from the National Cancer Institute.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Lydia Pace, Tharcisse Mpunga, Vedaste Hategekimana, Jean Bosco Bigirimana, Cadet Mutumbira, Cheryl Amoroso, Lawrence N. Shulman, Nancy Keating

Provision of study material or patients: Tharcisse Mpunga, Jean Bosco Bigirimana, Cadet Mutumbira, Egide Mpanumusingo

Collection and/or assembly of data: Lydia Pace, Tharcisse Mpunga, Vedaste Hategekimana, Jean-Marie V. Dusengimana, Hamissy Habineza, Jean Bosco Bigirimana, Jean-Paul Ngiruwera, Cheryl Amoroso

Data analysis and interpretation: Lydia Pace, Tharcisse Mpunga, Vedaste Hategekimana, Jean-Marie V. Dusengimana, Jean Bosco Bigirimana, Jean-Paul Ngiruwera, Neo Tapela, Cheryl Amoroso, Lawrence N. Shulman, Nancy Keating

Manuscript writing: Lydia Pace, Tharcisse Mpunga, Vedaste Hategekimana, Jean-Marie V. Dusengimana, Hamissy Habineza, Jean Bosco Bigirimana, Cadet Mutumbira, Egide Mpanumusingo, Neo Tapela, Cheryl Amoroso, Lawrence N. Shulman, Nancy Keating

Final approval of manuscript: Tharcisse Mpunga, Vedaste Hategekimana, Jean-Marie V. Dusengimana, Hamissy Habineza, Jean Bosco Bigirimana, Cadet Mutumbira, Egide Mpanumusingo, Jean-Paul Ngiruwera, Neo Tapela, Cheryl Amoroso, Lawrence N. Shulman, Nancy Keating

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM, et al. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;378:1461–1484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim NA, Oludara MA. Socio-demographic factors and reasons associated with delay in breast cancer presentation: A study in Nigerian women. Breast. 2012;21:416–418. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gakwaya A, Kigula-Mugambe JB, Kavuma A, et al. Cancer of the breast: 5-Year survival in a tertiary hospital in Uganda. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:63–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yip CH, Smith RA, Anderson BO, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: Early detection resource allocation. Cancer. 2008;113(suppl):2244–2256. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unger-Saldaña K. Challenges to the early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in developing countries. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:465–477. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, et al. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unger-Saldaña K, Infante-Castañeda C. Delay of medical care for symptomatic breast cancer: A literature review. Salud Publica Mex. 2009;51(suppl 2):s270–s285. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342009000800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez AJ, Westcombe AM, Burgess CC, et al. Factors predicting delayed presentation of symptomatic breast cancer: A systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353:1127–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson BO, Cazap E, El Saghir NS, et al. Optimisation of breast cancer management in low-resource and middle-resource countries: Executive summary of the Breast Health Global Initiative Consensus, 2010. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:387–398. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezeome ER. Delays in presentation and treatment of breast cancer in Enugu, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2010;13:311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jassem J, Ozmen V, Bacanu F, et al. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: A multinational analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:761–767. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma K, Costas A, Shulman LN, Meara JG. A systematic review of barriers to breast cancer care in developing countries resulting in delayed patient presentation. J Oncol 2012;2012:121873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.World Bank. Country and Lending Groups. 2014. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups. Accessed December 3, 2014.

- 14.Otieno ES, Micheni JN, Kimende SK, et al. Delayed presentation of breast cancer patients. East Afr Med J. 2010;87:147–150. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v87i4.62410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harirchi I, Ghaemmaghami F, Karbakhsh M, et al. Patient delay in women presenting with advanced breast cancer: An Iranian study. Public Health. 2005;119:885–891. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mousa SM, Seifeldin IA, Hablas A, et al. Patterns of seeking medical care among Egyptian breast cancer patients: Relationship to late-stage presentation. Breast. 2011;20:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thongsuksai P, Chongsuvivatwong V, Sriplung H. Delay in breast cancer care: A study in Thai women. Med Care. 2000;38:108–114. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ermiah E, Abdalla F, Buhmeida A, et al. Diagnosis delay in Libyan female breast cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:452. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ukwenya AY, Yusufu LM, Nmadu PT, et al. Delayed treatment of symptomatic breast cancer: The experience from Kaduna, Nigeria. S Afr J Surg. 2008;46:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farmer PE, Nutt CT, Wagner CM, et al. Reduced premature mortality in Rwanda: Lessons from success. BMJ. 2013;346:f65. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binagwaho A, Muhimpundu MA, Bukhman G. 80 under 40 by 2020: An equity agenda for NCDs and injuries. Lancet. 2014;383:3–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62423-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stulac S, Binagwaho A, Tapela N, et al. Building capacity for oncology programs in sub-Saharan Africa: The Rwanda experience. Lancet Oncol. 2014;11:251–259. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shulman LN, Mpunga T, Tapela N, et al. Bringing cancer care to the poor: Experiences from Rwanda. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:815–821. doi: 10.1038/nrc3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mpunga T, Tapela N, Hedt-Gauthier BL, et al. Diagnosis of cancer in rural Rwanda: Early outcomes of a phased approach to implement anatomic pathology services in resource-limited settings. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142:541–545. doi: 10.1309/AJCPYPDES6Z8ELEY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma K, Costas A, Damuse R et al. The Haiti Breast Cancer Initiative: Initial findings and analysis of barriers-to-care delaying patient presentation. J Oncol 2013;2013:206367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dye TD, Bogale S, Hobden C et al. Experience of initial symptoms of breast cancer and triggers for action in Ethiopia. Int J Breast Cancer 2012;2012:908547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Mody GN, Nduaguba A, Ntirenganya F, et al. Characteristics and presentation of patients with breast cancer in Rwanda. Am J Surg. 2013;205:409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ntirenganya F, Petroze RT, Kamara TB, et al. Prevalence of breast masses and barriers to care: Results from a population-based survey in Rwanda and Sierra Leone. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:903–906. doi: 10.1002/jso.23726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mugeni C, Levine AC, Munyaneza RM, et al. Nationwide implementation of integrated community case management of childhood illness in Rwanda. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2:328–341. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keating NL, Kouri EM, Ornelas HA, et al. Evaluation of breast cancer knowledge among health promoters in Mexico before and after focused training. The Oncologist. 2014;19:1091–1099. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malik IA, Gopalan S. Use of CAM results in delay in seeking medical advice for breast cancer. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:817–822. doi: 10.1023/a:1025343720564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohene-Yeboah M. Breast pain in Ghanaian women: Clinical, ultrasonographic, mammographic and histological findings in 1612 consecutive patients. West Afr J Med. 2008;27:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dickens C, Joffe M, Jacobson J, et al. Stage at breast cancer diagnosis and distance from diagnostic hospital in a periurban setting: A South African public hospital case series of over 1,000 women. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2173–2182. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson TP, O’Rourke DP, Burris JE, et al. An investigation of the effects of social desirability on the validity of self-reports of cancer screening behaviors. Med Care. 2005;43:565–573. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163648.26493.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx. Accessed February 10, 2015.

- 37.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) [Rwanda], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Rwanda], ICF International Rwanda: Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Calverton, MD: NISR, MOH, and ICF International, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MINECOFIN). Fourth Rwanda Population and Housing Census Rwanda: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), 2012. [Google Scholar]