Abstract

Men who have sex with men account for a disproportionate burden of HIV incidence in the USA. Although much research has examined the drivers of sexual risk-taking, the emotional contexts in which men make sexual decisions has received little attention. In this three-phase, 10-week longitudinal qualitative study involving 25 gay and bisexual men, we used timeline-based interviews and quantitative web-based diaries about sexual and/or dating partners to examine how emotions influence HIV risk perceptions and sexual decision-making. Participants described love, intimacy, and trust as reducing HIV risk perceptions and facilitating engagement in condomless anal intercourse. Lust was not as linked with risk perceptions, but facilitated non condom-use through an increased willingness to engage in condomless anal intercourse, despite perceptions of risk. Results indicate that gay and bisexual men do not make sexual decisions in an emotional vacuum. Emotions influence perceptions of risk so that they do not necessarily align with biological risk factors. Emotional influences, especially the type and context of emotions, are important to consider to improve HIV prevention efforts among gay and bisexual men.

Keywords: men who have sex with men, HIV, risk, emotions, USA

Introduction

Men who have sex with men accounted for 62% of new HIV infections in 2011 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013). Previous research addressing the drivers of sexual risk-taking, particularly condomless anal intercourse – the primary biological risk for HIV transmission – has examined societal and structural influences (e.g., minority stressors) (Finneran and Stephenson 2014; Meyer 1995, 2003), relationship characteristics (e.g., formal versus casual, monogamous versus non-monogamous) (Blashill et al. 2014; Davidovich, Wit, and Strobbe 2006; Hoff et al. 2012; Mustanski, Newcomb, and Clerkin 2011; Newcomb et al. 2014) and individual cognitive processes (Rogers and Prentice-Dunn 1997; Rosenstock 1974; Weinstein 1988). While some research has focused on emotions in same-sex male relationships, studies have not qualitatively examined the emotional processes that occur when men make sexual decisions, especially decisions between lower and higher risk experiences.

Research on emotional motivations of condomless anal intercourse has mostly examined casual or anonymous partners (Bauermeister et al. 2009; Berg 2009; Carballo-Diéguez and Bauermeister 2004; Carballo-Diéguez et al. 2011). Goodreau et al. (2012) and Sullivan et al. (2009) identified the importance of focusing on main partnerships, indicating that one- to two-thirds of new HIV infections among men who have sex with men are attributable to main partnerships. HIV transmission within main partnerships is shaped by more acts of condomless anal intercourse than occur with casual partners (Sullivan et al. 2009), but studies have not qualitatively examined motivations behind sexual risk-taking in main relationships, where there may be greater emotional connectivity.

A study conducted among lesbian, gay, and bisexual men and women found that compared to lesbian/bisexual women, gay/bisexual men reported higher romantic obsession (defined by obsessive and extreme thoughts, dependence, and other obsessive tendencies) (Bauermeister et al. 2012; Missildine et al. 2005); this was associated with higher reporting of sexual compulsivity, which could be used as measure of sexual risk (Missildine et al. 2005). A cross-sectional study of 24,787 gay and bisexual men found that more than 25% of men experienced feelings of love with their most recent sexual partner and found that sexual activities varied based on feelings of love (e.g., men who were unsure if they loved their partner but believed that their partner loved them were more likely to be the insertive partner during anal intercourse) (Rosenberger et al. 2014). Research has also explored condom use and emotions. Golub et al. (2012) examined men who have sex with men’s condom perceptions based on how condoms interact with risk, pleasure, and intimacy and found that men perceived condoms as an ‘interference’ with intimacy, which influenced sexual decision-making. Other research has identified more nuanced sexual decision-making based on intimacy and romantic relationship factors (Bauermeister et al. 2012; Bauermeister et al. 2011); in a cross-sectional study of 376 young men who have sex with men, Bauermeister et al. (2012) explained that romantic intentions and feelings can simultaneously be protective and risky. This study found that having feelings described as ‘romantic obsession’ were positively associated with a greater number of condomless anal intercourse partners, while experiencing ‘romantic ideation’ (defined as more ‘normative’ romantic thoughts) was associated with fewer condomless anal intercourse partners (Bauermeister et al. 2012).

Some studies have examined the influence of emotions in formal partnerships (Greene et al. 2014; Remien, Carballo-Diéguez, and Wagner 1995; Starks, Gamarel, and Johnson 2014; Theodore et al. 2004). A study of HIV sero-discordant male couples found that among HIV-negative partners, intimacy and sexual satisfaction were negatively associated with sexual risk-taking, while among HIV-positive partners, sexual satisfaction was positively associated with sexual risk-taking (Starks, Gamarel, and Johnson 2014). Greene et al.’s (2014) study of young male couples found that young men who have sex with men were engaging in condomless anal intercourse due to both logistical reasons (e.g., condom access) as well as emotional ones (e.g., trust and a desire to ‘connect’ with a partner), with results varying depending on relationship length.

All of these findings suggest that romantic or intimate emotions are present and important for men who have sex with men and that emotions have complicated and nuanced influences on sexual risk. However, more research is necessary to understand these nuances, especially as they differ across a variety of sexual partnerships. In this prospective qualitative study, we examine a variety of types of sexual and romantic relationships among gay and bisexual men to understand how emotions mediate their perceptions of sexual risk and sexual decision-making. We use a longitudinal qualitative approach that utilises visual timelines to capture the dynamic nature of emotions, relationships, and perceptions of sexual risk. This approach allows us to identify micro-shifts that occur as emotions and perceptions of risk changed over the study period. In addition, this approach provides a clearer understanding of participants’ overall relationship patterns in order to make better comparisons when understanding how risk-taking occurs.

Methods

Study population and recruitment

This study was approved by Emory University’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were men who previously participated in other studies at Emory University who were interested in participating in additional studies. Participants were eligible if they identified as a gay or bisexual man, were aged ≥18 years, lived in the Atlanta metropolitan area, and had had condomless anal intercourse in the past three months. We recruited 25 participants, all of whom completed the study. After 20 baseline in-depth interviews were completed and summarised, data were reviewed to assess saturation and variation according to participant demographics to target recruitment for the final five participants. The mean age for participants was 32.2 years, ranging from 19–50. Approximately half the participants identified as African American/Black (44%) and half were Caucasian/White (48%); two participants identified as another race. Almost all participants identified as gay/homosexual (92%), with two identifying as bisexual. Most participants were not in a committed relationship (68%) at the time of enrolment, which we defined as answering no the question: ‘Are you currently in a relationship with a man you feel committed to above all others? Some people might call this a boyfriend, life partner, husband, or significant other.’

Study procedures

During a 10-week study period, participants completed an individual in-depth baseline interview, three personal relationship diaries, and a debrief in-depth interview at closing. In total, 25 baseline interviews, 75 relationship diaries, and 25 debrief interviews were completed.

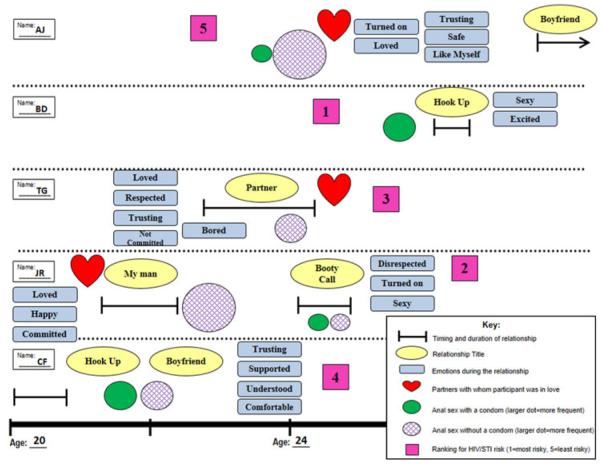

Baseline interviews followed a step-by-step process using a life-history timeline to retrospectively examine dating and sexual histories. Participants placed stickers with predetermined labels on the timeline in response to questions about relationship characteristics (e.g., partner type, commitment, exclusivity), emotions (e.g., love, trust, safety), experiences with anal sex (e.g., frequency, condom use, sexual decision-making), and perceptions of HIV and STI risk with each partner (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example of baseline interview timeline.

During the next phase of the study, participants completed three web-based personal relationship diaries (one every three weeks), answering quantitative questions about current sexual and/or dating partners. For each partner, diaries asked about commitment, how they met, relationship length, number of sexual encounters (oral, penetrative anal, and receptive anal), frequency of condom use, and rankings on a one to five scale (least to most) based on how well they knew the partner, emotional risk, and HIV/STI risk. Participants also chose applicable statements from a list of 26 that demonstrated a variety of emotions/relationship characteristics (e.g., ‘I get jealous when he flirts with other people’, ‘I trust him a lot’).

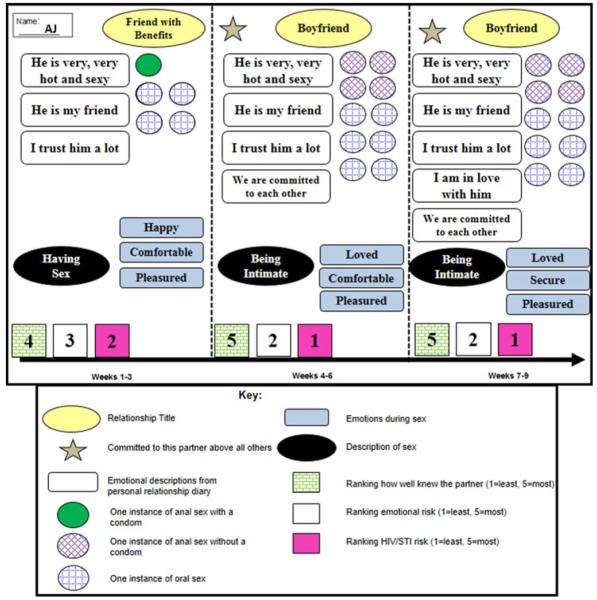

Diary data were unpacked in a timeline-based debrief interview examining emotions and sexual decision-making during the follow-up period. Participants followed a systematic, participatory process in which they were asked to qualitatively describe previously reported diary answers, which were represented on the timelines with stickers (Figure 2). Separate timelines were created for each partner, signifying changes between each relationship diary three-week period; participants were asked to further describe diary answers using predetermined labels that they added onto the timelines. Each debrief interview was tailored to diary responses, with modified interview guides addressing different types of responses (e.g., multiple versus one sexual partner, periods of abstinence).

Figure 2.

Example of debrief interview timeline.

Data analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Analysis was conducted using MAXQDA, version 10 (Verbi Software, Berlin, Germany). First, we completed a case-based analysis, examining data as individual life-stories. After multiple close readings, we created thick descriptions characterising each participant, summarising his relationships and identifying his relationship style, patterns of condom use, and risk definitions. This was augmented by a thematic analysis, examining patterns across participants within the context of each individual’s experiences.

The thematic analysis entailed the consistent application of a set of codes to all transcripts to examine how themes were discussed across participants and between groups of participants. A preliminary codebook was created based on close readings of several transcripts, incorporating explicit domains from interview guides as well as pervasive, unanticipated themes that were emergent across transcripts. Provisional definitions were given to each code and six analysts applied the codes to a single transcript. The coded transcripts were merged for comparison and code definitions were revised based on an examination of coding disagreement. This process was repeated until consistent agreement was attained among all coders.

Once the codebook was established, codes were applied to all transcripts, with at least two analysts coding each transcript. Focused readings of coded text produced thick descriptions for each theme. These descriptions identified common concepts, patterns, and unique statements that appeared in the transcripts. For the purpose of data retrieval by theme, types of respondents were grouped together based on age, race, relationship status, relationship development, HIV status (if disclosed), and patterns of condom use. Key quotes are presented here, using pseudonyms to protect the privacy of participants.

Results

Participants described a variety of relationships, including long- and short-term; monogamous and open; emotional and unemotional; frequent, occasional, and one-time encounters; and developing, diminishing, and steady relationships. Sexual decision-making and the formation of risk perceptions varied, but for each individual, that decision depended on the partner and relationship characteristics. The most common emotions described by participants were love, intimacy, trust, and lust.

Love

Participants frequently described feelings of ‘love’, ‘being head over heels’, ‘emotional connections’, and ‘emotional attachments’. At times, these terms were used interchangeably, but many participants also described strong emotional connections with partners that they did not define as love. These emotional connections and experiences of love were described as a ‘constellation’ or a ‘bunch of things’ that fit together to create a feeling or experience of love, including: ‘genuinely’ caring about someone, ‘emotionally investing’, feeling excited, having common interests, feeling comfortable, ‘knowing someone’, feeling as though someone will ‘always be there for you’, being willing to ‘do anything and everything I could to support him’, knowing that someone ‘won’t let you down’, ‘sharing your emotions’, taking ‘ownership and responsibility’ for someone’s happiness, feeling like ‘your day wouldn’t be complete without them in your life’, loving unconditionally, attraction, tenderness, intimacy, trust, respect, being ‘unselfish and less guarded with your heart’, and knowing that ‘you want to spend your life’ with someone.

Love was described as one-sided in some relationships and mutual in others. In one-sided experiences of love, this sometimes determined who had ‘control’ in the relationship:

He was more smitten with me than I was smitten with him. So I had more control at the beginning. But over time, falling in love and fear sometimes of losing him … I let go of the reins a little bit. (Zach, White, age 28)

This sense of giving up control and fear of relationship termination also played a role in definitions of ‘emotional risk’, a ranking question in the relationship diaries. Participants provided numerous explanations for emotional risk and stronger emotional attachments commonly meant that emotional risk was either very low or very high; low risk was because a participant had more confidence in the relationship and high risk was due to fear of losing the partner.

Mutual experiences of love were described as something that makes a relationship ‘more serious’ or involves a ‘deeper connection’; one participant described an ‘emotional connection’ as ‘potential … to go somewhere much more serious … potential of building a life together’ (Jordan, White, age 44). This sense of building a life together is where love and commitment overlapped. However, these relationship characteristics were not described as mutually exclusive because commitment existed in relationships that lacked love and vice versa.

Love and risk perceptions

Some participants considered their ‘safest’ partners to be the ones with whom they did not have any emotional attachments because they felt more ‘in control’ of these sexual encounters:

[My least risky partner] was my random act of kindness … it’s no scientific research to that but … That’s normally how I feel. I’m in control of the situation … There’s no emotional attachment afterwards and I feel safe, emotionally and physically and health-wise afterwards. (Victor, Black, age 30)

Participants like Victor, who had more casual relationships, considered partners with whom they shared emotional connections to be riskier because they were more likely to ‘let their guard down’ and ‘let love conquer them’. These partners were considered to have the greatest sexual risk because feelings of love meant a greater likelihood in engaging in condomless anal intercourse:

If I had [anal] sex with [this partner] it would have been [without a condom] too because I was so into him and so ready that it was just gonna be [without a condom]. I could trust him … I believed I could until I saw what I saw … I think the pattern is very common … when [people] feel like they love someone so much they are willing to risk life itself for that person knowing what this person’s status is or knowing their situation … Sometimes people let love conquer them and not their relationship. (Tyson, Black, age 26)

Many other participants (especially those engaging in formal relationships) linked a lack of emotional connection with a higher sexual risk. Cases where emotional connections changed over the study time period made this apparent because risk perceptions coincided with these changes. For example, Simon (White, age 24) described a partner who transitioned from ‘lover’ to ‘hookup’ in the relationship diaries. HIV/STI risk perception increased as this changed, which Simon explained as resulting from the level of emotional connection. Dean (White, age 19) described a similar situation in which his feelings for a partner decreased while his perception of HIV/STI risk increased. In this case, this resulted from a specific event that had occurred:

All these [risk ranking] numbers kind of correspond, like how well I knew him dropped. The emotional risk dropped. But the HIV and STI risk increased. He had just more of a negative connotation after that … I guess probably because I was feeling a certain kind of way about him because of him and my brother fighting, I think that’s probably why he got lower scores. Not because they’re necessarily the most conscious things but just because I was feeling a certain way about him. Because I don’tthink between threeweeks and six weeks he increased drastically inhis HIV and STI risk or anything. Just it’s more of a mental thing. (Dean, White, age 19)

Here, the difference in the perception of risk is described as something ‘mental’ rather than an actual change in HIV/STI risk. However, this mental change can be important when it facilitates sexual decision-making.

Love and sexual decision-making

Love was described as beingassociated with ‘lustful feelings’. Different sex acts were described as more associated with loving feelings than others, which translated into sexual decision-making based on emotional connections. In most cases, anal sex was perceived as a more intimate activity, but a few participants described oral sex as ‘more loving’. Some participants described ‘saving’ certain activities for partners with greater emotional connections: ‘There’s something that’s kind of reserved for romantic situations’ (Dean, White, age 19).

According to participants, an emotional connection and an increased sense of comfort can lead to a perception of reduced risk, which facilitates condomless anal intercourse:

I think there’s probably a misconception that the more comfortable you feel with someone the less of a risk that there is. But I know that’s not true, but I think that’s how a lot of people feel … you mentally think that their risk goes down because you feel more comfortable with them. So I think that use of condoms probably decreases as you go along. (James, Multiracial, age 35)

I think I just fell really hard for [him] because I don’t think we used a condom but once or twice. Looking back, stupid just because of where he came from and knowing the life he was living. But in my heart, and I know you shouldn’t base it on what’s in your heart or your feelings, but I just knew that there was no trouble there. (Logan, White, age 32)

Participants also discussed being more willing to engage in condomless anal intercourse if their partner considered them to be a ‘priority in the love department’ (Logan, White, age 32). Some participants also described their partners’ willingness to engage in condomless anal intercourse because of emotional connections: ‘Both of them [were] very deeply emotionally attached to me … I wanted to more than they did. And they did it for me or they allowed me to’ (Brian, Black, age 28). In these cases where condom decision-making was based on mutual emotional connections, perceptions of sexual risk were frequently reduced and condomless anal intercourse was used as a way to increase the connection between partners.

Intimacy

Intimacy was commonly defined by participants in terms of sex, but was also described as completely separate from sex because ‘you can be intimate with somebody and not have sex with them’ (Jared, Black, age 42). Intimacy included physical affection (e.g., cuddling, kissing), participating in activities together (e.g., cooking, going to the movies), sharing intimate details about oneself (e.g., sexual histories, family histories, difficult experiences), and experiences of commitment and exclusivity. Intimacy was also defined in terms of an emotional connection and, for some participants, was closely linked with feelings of love. However, intimacy was also described as a separate domain from love; intimacy was described in terms of actions and romantic, physical, and/or sexual activities in addition to emotions, while love was described more explicitly in terms of feelings.

Intimacy and risk perceptions

Participants described how intimacy leads to a perceived reduced sexual risk because it makes one feel ‘less guarded’. A perception of increased ‘safety’ due to intimacy is not necessarily based on increased risk management, but rather on assumptions from increased comfort:

I knew him more, a little bit more intimately. I can’t say that I know him perfectly well but I know him well enough to know that it’s a safe situation and so I felt more comfortable … I know there’s a 99.99999% chance he’s not carrying any STIs … just because I know him there is a greater level of intimacy there, that’s why, I think I felt more safe. (Seth, White, age 35)

Multiple participants described ‘safety’ based on increased intimacy and, according to some, intimacy was enough reassurance to believe that a partner was not a risk to sexual health.

Intimacy and sexual decision-making

Participants identified using condoms in relationships that lacked intimacy: ‘We had non-intimate conversation. Didn’t really know him, so I used the condom’ (Henry, Black, age 24). In intimate relationships, participants described being more likely to engage in condomless anal intercourse because they were ‘less guarded’:

I would probably connect [HIV/STI risk] to I wanted to feel close and connected to him, comfortable as being intimate … when you feel comfortable with someone, in a way you let your guard down physically. And so you may do things that you don’t ordinarily do just with a random person that you meet … eventually you may have unprotected sex. (Mark, Multiracial, age 24)

Many participants described seeking a level of intimacy that results from non-condom use; in this context, condomless anal intercourse was perceived as a symbol of intimacy and commitment – a sign that the relationship was more formal:

I think there’s always the excuse out there [to not use condoms], that it feels better or whatever. I don’t believe that and the reason I don’t believe that is because once you’re having sex, you’re enjoying it no matter what. I personally think that for us, and I can only speak for us as a couple, that it forms a bond and a level of intimacy that … when you take that condom away, it also takes away the maybe like boyfriend status and it’s like OK, this is committed. So because we’re committed, we’re taking this step. So maybe it’s also an indirect unsaid step from one level to the next and I think that it is a trust level and it is a trust action. (James, Multiracial, age 35)

Trust

Trust was a dynamic concept. Some participants described trust as being built over time while others described it as simply being there (or not). In some cases trust was equated with comfort, but some participants described a greater level of ‘trusting him with my life’. This level of trust was based on the idea that a partner would never intentionally do anything to harm the participant, such as transmitting an STI or HIV. Development of trust was most commonly based on explicit or implicit sexual agreements regarding monogamy or non-monogamy and the likelihood that a partner would keep or break an agreement.

Trust and risk perceptions

Trust based on sexual agreements strongly determined perceptions of sexual risk; monogamous partners were especially considered to be more trustworthy and the least risky for HIV/STIs: ‘[He was less risky because] we are committed. I have no reason to distrust him ever. We’re monogamous’ (Leo, White, age 50).

For some participants, non-monogamy simultaneously reduced trust and increased the perception of sexual risk. This was especially the case if expectations and agreements regarding monogamy changed during the course of the relationship:

[Him being on an online hookup site] caused a lot of distrust … because when I would have sexual encounters with him … I would always have this thought in the back of my mind like am I going to contract something? What am I getting into bed with? Whereas before, it purposely wasn’t like that, when there was more exclusivity. (Simon, White, age 24)

This did not apply to all participants. For some participants, trust and risk were not based on monogamy; instead, increased risk perceptions resulted from a lack of honesty about outside partners and the breaking of agreements:

We never had a commitment to be monogamous, even though I was while we were together. He claimed he was going to be but I knew, based on knowing him, that that wasn’t going to be the case. And so I told him, ‘I don’t want that hype but I do want you to be honest with me … if you’re out playing around then I want to know about it. I’m not saying you can’t, I’m just saying you need to be honest with me about what you’re doing’ … I expect honesty and if I’m being lied to then I have a big problem with that. (Jordan, White, age 44)

Most participants also discussed risk perceptions and trust in terms of agreement-breaking. Partners who were perceived as the most trustworthy and the least risky were those who were perceived as least likely cheat. This ‘likelihood to cheat’ was determined based on the perception that a partner ‘would have never done anything to put me at risk or anything like that’ (Seth, White, age 35). Participants also stated that this trust meant that if a partner did cheat, that he would still ensure the participant’s safety in terms of sexual risk:

I trust him, the fact that I don’t think he’s playing around or cheating on me. And I trust that if he did, he would tell me and we would take more appropriate actions even if that meant starting back to use condoms for a while until we made sure. (Jordan, White, age 44)

The perception of a partner’s likelihood to cheat or not cheat was also based on emotional connections, especially if a participant felt that their partner had a strong emotional connection to them:

Interviewer: What does that mean to trust him?

Seth: I knew that he had really strong emotions towards me and I knew that he wasn’t interested in anyone else and that he wasn’t having sex with anyone else. So that’s how I trusted that he wasn’t going to give me any STIs. (White, age 35)

Seth explicitly stated that his risk ranking was related to his perception of his partners’ emotions, ‘whether I know they’re wholly devoted to me or not’ (Seth, White, age 35).

Trust and sexual decision-making

Feelings of trust also influenced sexual decision-making, especially decisions around condom use: ‘That level of trust, it just didn’t need a condom because I trusted him that much that I knew that he would be safe with my body’ (Dean, White, age 19). When participants felt that partners were going to protect their sexual health, they were more likely to engage in condomless anal intercourse. Since trust was also based on sexual agreements, greater condom use occurred among partners who had outside partners or who were likely to cheat:

Because we was no longer exclusive, so I didn’t know who he had been with and I’m protecting myself … I told him you have to use a condom … Before because we was exclusive, [we didn’t use condoms]. But now that we’re not, I don’t know who you with, what you doing, so in order to protect me, that is why I said we’re going to have to use a condom. (Fred, Black, age 44)

For some participants, the point where condomless anal intercourse became more likely was when the partners had an explicit conversation to be monogamous: ‘Once we had the, OK, we’re being monogamous and we’ve had our test then we pretty much just stopped using condoms’ (Jordan, White, age 44). Condomless anal intercourse was more common in monogamous or exclusive relationships because of the level of trust:

At first we started using [condoms] but then … because we’re boyfriends we didn’t use them anymore because we trusted each other … [Trust] is like an assumption, but you feel strongly about the person to where you think they wouldn’t do anything to hurt you or anything. (Mark, Multiracial, age 24)

In some cases, condomless anal intercourse was also used to build trust and demonstrate monogamy: ‘When we first started out, he wanted to use condoms and then we built up that trust and we decided to experiment without the condom and I didn’t want him not to trust me so I did it’ (Nate, Black, age 29). Multiple participants stated that the trust built from condomless anal intercourse was also considered to be a sign of ‘commitment’:

We were in the middle of having sex and I think we both had already disclosed that we both were negative; we hadn’t been with other people … and I said to him, ‘do you want me to put on a condom?’ And he said, ‘it’s up to you’ … and I think that was his way of saying, ‘I trust you but I want you to feel comfortable’ … So I didn’t [use a condom] and … neither of us has since then. So I think that it’s little experiences that develop into trust and go from maybe boyfriend over to partnership because that’s a big commitment. (James, Multiracial, age 35)

Some participants described scenarios where trust was lacking and condomless anal intercourse was considered proof that neither partner would have sex with anybody else: ‘So his thing was if you don’t trust me not to have sex with you without a condom then we don’t need to be together’ (Jared, Black, age 42). This necessity to engage in condomless anal intercourse as proof of fidelity was considered a very negative experience:

With [this partner], we never used a condom because he looked at a condom as I was cheating on him, which scared the hell out of me … When I pulled out a condom, he’s like, ‘What do we need that for? You’re not cheating on me, are you?’ And that’s where the physical unsafe part was. (Victor, Black, age 30)

Lust

Lust was defined as a ‘sexual attraction’ or a ‘physical thing’ that sometimes was present in emotionally intimate relationships, but could exist without any other emotional connections. Love and lust were described as two very different feelings; however, participants recognised that sometimes they could be confused. Participants described lust and experiences of sexual pleasure as mediating decisions about sex. Lust functioned differently than other emotions, as it had only a small impact on risk perceptions, but facilitated a participant’s willingness to engage in condomless anal intercourse despite perceived risks.

Lust and risk perceptions

When participants associated lust with risk perceptions, they described lust as increasing risk because it can facilitate increased sexual risk-taking:

Pleasure [most influenced how I ranked him for HIV risk] because now I’m realising that I need to keep my guard up because I’m enjoying it as well … meaning I need to make sure that … am I the bottom, am I the top, because if I’m pleasuring myself, maybe I’m pleasuring myself in different type of sexual activity now … just because I’m feeling good … let me still keep my eyes open because now I’m starting to enjoy this. (Victor, Black, age 30)

Participants recognised that increased feelings of lust and pleasure could lead to different types of sexual activities that could be riskier, therefore increasing the perception of sexual risk.

Lust and sexual decision-making

The experience of being ‘so into him’, describing someone as ‘hot’, and experiencing lust facilitated sexual decisions that participants described as risky and atypical. For example, Brad (White, age 29) described a sexual experience in which he engaged in condomless anal intercourse with a HIV-positive partner:

It was a lot of fun but I just was nervous the whole time. And the problem that I had going against me is that he is very, very hot and sexy and it’s like the struggle I’m having with what my brain is telling me to not do versus like what my eyes want and the hands want to do. (Brad, White, age 29)

Other participants also described this same phenomenon of knowingly engaging in sexual risk-taking behaviours due to attraction: ‘I don’t trust him to not be free of STIs and there’s an element of it being unsafe but … at least felt like during the time that the risk was worth the reward’ (Seth, White, age 35).

In some cases, however, participants described experiences that were ‘fun’ or ‘passionate and intense’ during which they did not engage in condomless anal intercourse. One of the youngest participants (Paul, White, age 22) described an experience where ‘he was pretty fun in bed’ but because condoms were not available, they did not engage in anal intercourse, despite wanting to do so. For a few participants, describing a partner as ‘hot and sexy’ made them even more likely to use condoms because they were under the assumption that being ‘hot’ meant that this partner was likely to have a lot of other partners. Though a few participants perceived increased attraction as a reason to use condoms, participants more commonly expressed experiences where lust alone informed the decision to engage in condomless anal intercourse, even when they perceived that behaviour as risky.

Willingness to take a risk

Although love, intimacy, and trust all mediated sexual decision-making through risk perceptions, lust mediated sexual decision-making by causing one to overlook the possibility of risk. Many participants, especially those who were not in formal relationships, described their ‘willingness’ to take a risk:

I have a certain tolerance for risk. I’m kind of OK with getting a blow job in a sex club. I’m kind of OK with having anal sex with somebody who I don’t really know that well, protected but … I have a relatively high tolerance for risk when it comes to this sort of thing and I’ve had an STD before, so I know that I’m human and can definitely get it. I’ve been very, very, very lucky with respect to the encounters that I’ve had and the things that could have happened to me. So, I’m thankful for that but at the same time I know that if I keep on doing this crap that it’s going to bite me and then I am going to get something that you can’t wash off. (Seth, White, age 35)

Discussion

Results presented here suggest that: perceptions of sexual risk are frequently skewed by emotions, resulting in a perception of risk that is unaligned from the potential biological risk; the type of emotion is important when considering risk perceptions and sexual risk-taking; and the context of the relationship in which these emotions occur impact the way in which emotions influence sexual risk perceptions and risk-taking.

On most participants’ timelines, risk rankings contradicted their actual behaviour. Partners with whom the participant had the most condomless anal intercourse were often considered the least risky in terms of HIV/STIs. In contrast, partners with whom participants had infrequent or one-time experiences of anal intercourse with a condom were often considered to be the riskiest partners. In some cases, this was simply the result of the participant making a decision based on how they perceived the risk of that particular partner; however, for most participants, this discrepancy between a perception of risk and the level of risk of the actual behaviour was fuelled by love, intimacy, and trust. When love, intimacy, or trust were present in a relationship, a partner was not perceived as a high risk, despite the sexual behaviours that occurred in the relationship and the actual risk of exposure.

The specific type of emotion is important to understand when considering how emotions shape perceptions of risk and facilitate sexual decision-making. Most commonly, love, intimacy, and trust reduced perceptions of risk, thus increasing willingness to participate in condomless anal intercourse. While these emotions frequently overlapped, they were all described separately by participants. Love caused participants to ‘take their guard down’, intimacy created an increased comfort and a sense of knowing their partner better, and trust was typically described in terms of the level of devotion or commitment in the relationship and sexual agreements about monogamy or non-monogamy. Lust was unique because it increased a willingness to engage in condomless anal intercourse regardless of the perception of risk. When considering a cost-benefit analysis (Suarez and Kauth 2001; Suarez and Miller 2001) for sexual decision-making, lust influenced decisions so that the benefits of engaging in condomless anal intercourse were such that the potential cost was no longer a factor. However, the concept of lust was more complex than simply explaining condomless anal intercourse as an increased benefit. The experience of attraction and the increase of pleasure was compared to ‘a drug’ that lowers inhibitions and inhibits the ability to control decision-making.

Relationship contexts were also important in shaping risks. For example, one participant described a casual relationship in which he experienced intimacy. He chose to engage in condomless anal intercourse with this partner and felt comfortable in doing so because of the level of intimacy; however, he perceived this action as very risky because the relationship was casual and non-monogamous. On the contrary, when intimacy was experienced in more formal and monogamous relationships, participants engaged in similar behaviours, but did not perceive them as risky. These findings support previous literature about sexual agreements and relationship characteristics that suggest that greater relationship commitment and trust are associated with increased condomless anal intercourse because of explicitly stated sexual agreements that determine rules about monogamy and concurrency (Hoff et al. 2012; Mitchell et al. 2012; Mustanski, Newcomb, and Clerkin 2011). These agreements may lead to a practice of ‘negotiated safety’, in which condomless anal intercourse occurs only after agreements are made about HIV testing and outside partners (Davidovich, Wit, and Strobbe 2006). Micro-shifts in the development of relationships also influenced emotions, which simultaneously impacted perceptions of risk and sexual decision-making. Many participants described specific events in which the development of a relationship changed; these specific moments were key in capturing descriptions of how love, intimacy, and trust can alter perceptions of risk. Some of these micro-shifts occurred during pivotal moments of sexual decision-making, as seen in James (Multiracial, age 35), who described his first act of non-condom use with a partner as a sign of deepening commitment and trust.

Messaging for HIV prevention and condom use may be more useful if it targets intimate aspects of relationships among men who have sex with men. The emotional components of same-sex male relationships should not be ignored, but they also should not be perceived as simply a risk factor. As seen in the literature, these emotions can be complex; for example, Bauermeister et al. (2012) found that healthy ‘romantic ideation’ may reduce the number of partners with condomless anal intercourse. Messaging should encourage risk-reducing behaviours in loving relationships, indicating that love is not necessarily a protective factor for sexual risk. Simultaneously, this messaging should be careful to not discourage the existence of loving same-sex male relationships (Mustanski and Parsons 2014). Instead, these messages can promote HIV interventions such as increased condom use, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and HIV testing by recognising that decisions about HIV risk occur within an emotional context. This means that interventions could also include the establishment of explicit sexual agreements (Mitchell et al. 2012) and couple-based interventions (Purcell et al. 2014), such as couples HIV counselling and testing (Mitchell 2014; Stephenson et al. 2011; Sullivan et al. 2014; Wagenaar et al. 2012).

There are some limitations to this research. Participants were limited to discussing five previous partners in the baseline interview and three partners in each relationship diary. All relationships observed during follow-up were limited to a 10-week window of relationship development. Due to the qualitative nature of the data, results are not transferable beyond the urban population of gay and bisexual men in Atlanta. All participants identified as gay or bisexual, limiting the ability to understand the experiences men who have sex with men in general. Despite these limitations, this study incorporated an innovative longitudinal approach to understand the complexities of the impact of emotions on sexual risk-taking.

These data elucidate the importance of understanding emotional contexts in sexual decision-making. For gay and bisexual men, the negotiation of condom use does not typically occur in a space void of emotion, but rather within the larger emotional context of a relationship. These contexts shape motivations and self-efficacy for condom use (or nonuse) and are important to recognise when considering HIV prevention. These emotional contexts create additional layers of condom negotiation that go beyond education and knowledge of HIV transmission – participants identified engaging in risky behaviour despite being knowledgeable about HIV/STIs. In some cases, education encouraged risk-reducing activities; however, participants also knowingly engaged in risky behaviours despite knowledge of safer sex strategies. In order to be more successful, HIV prevention efforts need to go beyond providing education and consider all of the emotional contexts that occur when men engage in sexual risk-taking behaviours despite ‘knowing better’.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was funded by the University Research Committee at Emory University and the Center for AIDS Research at Emory University [grant number P30AI050409].

References

- Bauermeister JA, Carballo-Diéguez A, Ventuneac A, Dolezal C. Assessing Motivations to Engage in Intentional Condomless Anal Intercourse in HIV Risk Contexts (“Bareback Sex”) among Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(2):156–168. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Leslie-Santana M, Johns MM, Pingel E, Eisenberg A. Mr. Right and Mr. Right Now: Romantic and Casual Partner-seeking Online among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(2):261–272. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9834-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Ventuneac A, Pingel E, Parsons JT. Spectrums of Love: Examining the Relationship between Romantic Motivations and Sexual Risk among Young Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS & Behavior. 2012;16(6):1549–1559. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0123-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC. Barebacking: A Review of the Literature. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(5):754–764. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill A, Wilson J, O’Cleirigh C, Mayer K, Safren S. Examining the Correspondence between Relationship Identity and Actual Sexual Risk Behavior among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):129–137. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0209-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Bauermeister J. ‘Barebacking’ Intentional Condomless Anal Sex in HIV-risk Contexts. Reasons for and against it. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47(1):1–16. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Ventuneac A, Dowsett GW, Balan I, Bauermeister J, Remien RH, Dolezal C, Giguere R, Mabragaña M. Sexual Pleasure and Intimacy among Men Who Engage in “Bareback Sex”. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(1):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9900-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Surveillance Report, 2011. 2013;Vol 23 Accessed http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/ [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich U, Wit J, Strobbe W. Relationship Characteristics and Risk of HIV Infection: Rusbult’s Investment Model and Sexual Risk Behavior of Gay Men in Steady Relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2006;36(1):22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Finneran C, Stephenson R. Intimate Partner Violence, Minority Stress, and Sexual Risk-taking among U.S. Men Who Have Sex with Men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2014;61(2):288–306. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.839911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, Starks TJ, Payton G, Parsons JT. The Critical Role of Intimacy in the Sexual Risk Behaviors of Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS & Behavior. 2012;16(3):626–632. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9972-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, Lama JR, Sanchez J, Grinsztejn B, Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Buchbinder SP, Sullivan PS, Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, Lama JR, Sanchez J, Grinsztejn B, Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Buchbinder SP. What Drives the US and Peruvian HIV Epidemics in Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM)? PloS ONE. 2012;7(11):e50522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GJ, Andrews R, Kuper L, Mustanski B. Intimacy, Monogamy, and Condom Problems Drive Unprotected Sex among Young Men in Serious Relationships with Other Men: A Mixed Methods Dyadic Study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):73–87. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0210-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff CC, Chakravarty D, Beougher SC, Neilands TB, Darbes LA. Relationship Characteristics Associated with Sexual Risk Behavior among MSM in Committed Relationships. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26(12):738–745. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missildine W, Feldstein G, Punzalan JC, Parsons JT. S/he Loves Me, S/he Loves Me Not: Questioning Heterosexist Assumptions of Gender Differences for Romantic and Sexually Motivated Behaviors. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2005;12(1):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. Gay Male Couples’ Attitudes toward Using Couples-based Voluntary HIV Counseling and Testing. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):161–171. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JW, Harvey SM, Champeau D, Moskowitz DA, Seal DW. Relationship Factors Associated with Gay Male Couples’ Concordance on Aspects of their Sexual Agreements: Establishment, Type, and Adherence. AIDS & Behavior. 2012;16(6):1560–1569. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0064-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Newcomb ME, Clerkin EM. Relationship Characteristics and Sexual Risk-taking in Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. Health Psychology. 2011;30(5):597–605. doi: 10.1037/a0023858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Parsons JT. Introduction to the Special Section on Sexual Health in Gay and Bisexual Male Couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):17–19. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M, Ryan D, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. The Effects of Sexual Partnership and Relationship Characteristics on Three Sexual Risk Variables in Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):61–72. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell D, Mizuno Y, Smith D, Grabbe K, Courtenay-Quirk C, Tomlinson H, Mermin J. Incorporating Couples-based Approaches into HIV Prevention for Gay and Bisexual Men: Opportunities and Challenges. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):35–46. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remien RH, Carballo-Diéguez A, Wagner G. Intimacy and Sexual Risk Behaviour in Serodiscordant Male Couples. AIDS Care. 1995;7(4):429–438. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RW, Prentice-Dunn S. Protection Motivation Theory. In: Gochman DS, editor. Handbook of Health Behavior Research I: Personal and Social Determinants. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1997. pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger J, Herbenick D, Novak D, Reece M. What’s Love Got to Do with it? Examinations of Emotional Perceptions and Sexual Behaviors Among Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):119–128. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Education & Behavior. 1974;2(4):354–386. [Google Scholar]

- Starks TJ, Gamarel KE, Johnson MO. Relationship Characteristics and HIV Transmission Risk in Same-sex Male Couples in HIV Serodiscordant Relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(1):139–147. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Sullivan PS, Salazar LF, Gratzer B, Allen S, Seelbach E. Attitudes Towards Couples-based HIV Testing Among MSM in Three US Cities. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(S1):80–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9893-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez T, Kauth MR. Assessing Basic HIV Transmission Risks and the Contextual Factors Associated with HIV Risk Behavior in Men Who Have Sex with Men. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57(5):655–669. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez T, Miller J. Negotiating Risks in Context: A Perspective on Unprotected Anal Intercourse and Barebacking among Men Who Have Sex with Men—Where Do We Go From Here? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2001;30(3):287–300. doi: 10.1023/a:1002700130455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, Sanchez TH. Estimating the Proportion of HIV Transmissions from Main Sex Partners among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Five US Cities. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1153–1162. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, White D, Rosenberg ES, Barnes J, Jones J, Dasgupta S, O’Hara B, et al. Safety and Acceptability of Couples HIV Testing and Counseling for US Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Randomized Prevention Study. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC) 2014;13(2):135–144. doi: 10.1177/2325957413500534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodore PS, Durán REF, Antoni MH, Fernandez MI. Intimacy and Sexual Behavior among HIV-Positive Men-Who-Have-Sex-with-Men in Primary Relationships. AIDS & Behavior. 2004;8(3):321–331. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000044079.37158.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar BH, Christiansen-Lindquist L, Khosropour C, Salazar LF, Benbow N, Prachand N, Sineath RC, Stephenson R, Sullivan PS, Niccolai LM, Wagenaar BH, Christiansen-Lindquist L, Khosropour C, Salazar LF, Benbow N, Prachand N, Sineath RC, Stephenson R, Sullivan PS. Willingness of US Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) to Participate in Couples HIV Voluntary Counseling and Testing (CVCT) PloS ONE. 2012;7(8):e42953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND. The Precaution Adoption Process. Health Psychology. 1988;7(4):355–386. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]