Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

Identifying pancreatic cancer patients at high risk of early mortality following surgical resection for pancreatic cancer is important to make optimal treatment decisions in multidisciplinary setting. The purpose of this study was to identify the factors related to early mortality in patients who underwent pancreatic resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Methods

We reviewed our institution's experience with all consecutive patients who underwent pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma from January 2000 to December 2010. One thousand patients were eligible for our study. Fifty-three patients who did not meet the study criteria were excluded. Based on 12 months after surgery, patients were divided into early mortality group or the remaining group. We performed logistic regression analysis to identify predictors of early mortality.

Results

Among 947 patients who met our study criteria, 302 (31.9%) early mortality (defined as experiencing death within 12 months after surgery) occurred. Multivariate analysis revealed that patient age and surgery time period were statistically significant predictors of early mortality within six months after surgery. Poorly differentiated tumor and adjuvant chemotherapy were statistically significant predictors of early mortality within 12 months after surgery. Total pancreatectomy and lymphovascular invasion were significant (p<0.05) prognostic factors of early mortality within 6 or 12 months after surgery.

Conclusions

We suggest followings to avoid early mortality after pancreatic resection: patients with multiple risk factors related to early mortality after pancreatectomy should be considered for alternative treatment; patient's general condition and surgical technique improvement are important; and adjuvant therapy should be taken into consideration.

Keywords: Pancreas, Pancreatic cancer, Pancreatectomy, Survival, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer remains a lethal disease. It has high mortality rate due to the aggressive nature of the tumor and its asymptomatic disease progression leading to delayed diagnosis. Pancreatic cancer has an estimated 20% resectability at diagnosis and an overall five-year survival of 5%.1,2,3 Surgery remains the only curative treatment. Complete pancreatic resection showed actuarial five-year survival rates of 15-25% following pancreaticoduodenectomy4,5,6 and 8-14% following distal pancreatectomy.7,8 The common causes of treatment failure after pancreatic cancer resection have been locoregional recurrence and/or the development of distant metastases. The persistence or recurrence of locoregional disease has been discovered in as many as 80% of patients who has undergone curative resection.9

Cumulative survival curve after resection for pancreatic cancer shows a rapid decline pattern during the early postoperative period followed by a subtle downward pattern. Such early mortality after pancreatectomy may be attributed to inadequate pre- or intraoperative tumor staging, the very aggressive nature of the disease, surgery-related factors, or unknown causes. Identifying patients at high risk for early mortality is important to make the optimal decision regarding the most appropriate treatment for these patients before surgery.

A few studies described early mortality of patients following pancreatic surgery for pancreatic cancer.10,11,12 However, high-volume study has not been reported. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the characteristics related to early mortality in patients who has undergone pancreatic resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a high-volume population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010 in the Department of Surgery of Asan Medical Center in Seoul, Korea, we performed pancreatic surgery for 1,310 patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Various types of surgery were performed, including distal pancreatectomy, total pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, hepatopancreaticoduodenectomy, median-saving pancreatectomy, uncinate resection, and central pancreatectomy. Among these patients, 1,000 (76.4%) were histologically diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma after their surgery who met our inclusion criteria. Data were retrospectively collected from medical records. All database regarding patient follow-up, survival, and tumor recurrence had been updated until March 2014. According to medical records review, disease recurrence was confirmed by computed tomographic scan and/or magnetic resonance imaging and/or a Positron emission tomography scan. In the study group, 47 patients were lost during follow-up. Data regarding death and other clinical information were obtained by telephone interview with the patient's family.

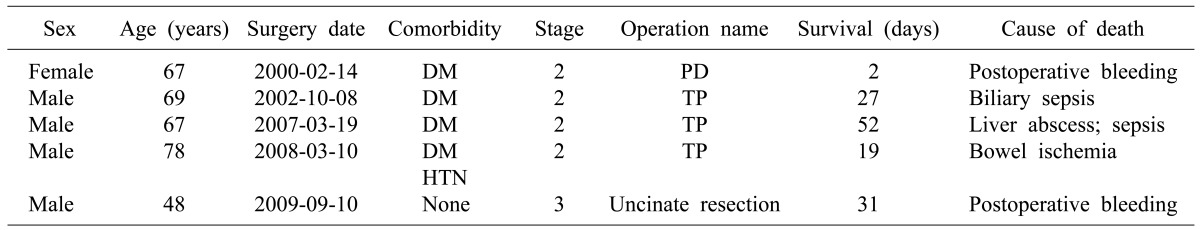

We defined postoperative mortality as in-hospital deaths related to surgery. Five study patients died due to postoperative mortality. Table 1 shows the information and cause of death of patients with surgery-related mortality. In the study group, there were four cases of non-disease-related death, including asphyxia (n=1), pneumonia (n=1), cerebral infarction (n=1), and opioid overuse (n=1). Data from patients who died due to surgery-related cause (n=5) or non-disease-related causes (n=4) were excluded from this study. Stage IV disease patients with distant metastasis at the time of their surgery (n=44) were also excluded. Therefore, a total of 947 patients were included in our analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics and cause of death in surgery-related mortality cases

Tumor staging according to the AJCC 7th edition staging guidelines. PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; TP, total pancreatectomy; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension

There is no clear definition or consensus regarding early mortality after pancreatic surgery for pancreatic cancer. We arbitrarily defined early mortality as death within 12 months after pancreatectomy which has been used in other published studies.9,11

Patient characteristics

Medical records of patients were retrospectively reviewed. Prognostic factors related to early mortality after pancreatic resection for pancreatic cancer were evaluated according to the following variables: clinicopathologic data, preoperative laboratory data, operative data, and postoperative treatment. Analyzed factors were clinical features (patient age, time period during which surgery was performed, type of surgery, postoperative hospital stay, diabetes mellitus, patient smoking history, symptoms including abdominal pain and/or backpain, indigestion, and weight loss), histological features (tumor stage, location, size, and differentiation, lymph-node status, metastasis, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, resection margin), pre-operative laboratory examination data (CA 19-9 and/or CEA, total bilirubin, albumin, hemoglobin), surgical data (portal-vein resection, artery resection including celiac axis, common hepatic artery or superior mesenteric artery), and postoperative treatment (adjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant radiation). Regarding smoking, we included all patients, i.e., current smokers and ex-smokers. Preoperative laboratory values were recorded with the highest values (CA19-9, CEA, total bilirubin) or the lowest values (albumin, hemoglobin). Tumor staging was evaluated according to the pancreatic cancer classification defined by the 7th AJCC.

Statistical analysis of the prognostic factors

Patient survival was defined as the time from resection to death. The actual survival rate was estimated using Kaplan-Meier method. Log-rank test was used to compare survival rate in different patient subgroups. Fisher's exact test was used to compare prognostic factors between the early mortality group and the remaining group. The prognostic factors associated with early mortality (death within 12 months after surgery) were investigated using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. SPSS software (version 18.0) was used for statistical analyses. Statistical significance was considered when p-value was less than 0.05.

RESULT

Survival outcome

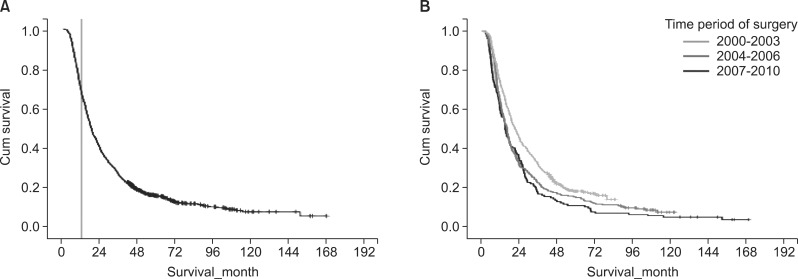

The median follow-up for our study population (n=947) was 19.0 months. The median disease-specific survival was 18.6 months. The cumulative survival curve of the study population is shown in Fig. 1. Median disease-specific survival of the early mortality group and the remaining group was 8.3 months and 28.9 months, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patient survival. (A) Disease-free survival rate of all 947 patients who underwent surgical resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Landmark line showing 12 months; (B) Comparison of the disease-free survival rate stratified according to the time period during which surgery was performed.

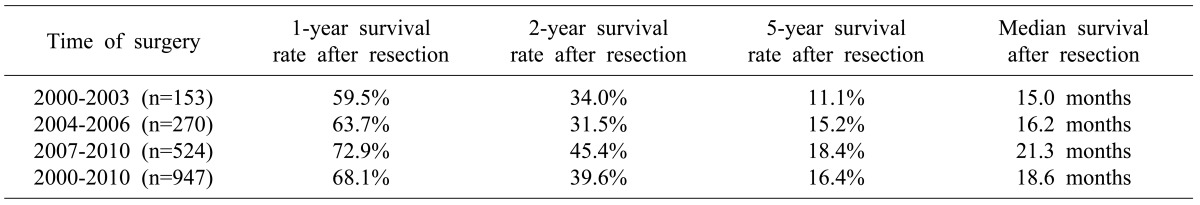

We divided the 947 cases according to three time periods: 2000-2003, 2004-2006, and 2007-2010. There were 153 (16.2%) cases in 2000-2003, 270 (28.5%) cases in 2004-2006, and 524 (55.3%) cases in 2007-2010. The median survival of 2000-2003, 2004-2006, and 2007-2010 time period was 15.0, 16.2, and 21.3 months, respectively. Log-rank test revealed statistically significant (p<0.001) difference in survival among the three groups. The one-, two-, and five-year survival rates were also improved according to the time period of surgery performed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survival analysis according to the time of surgery

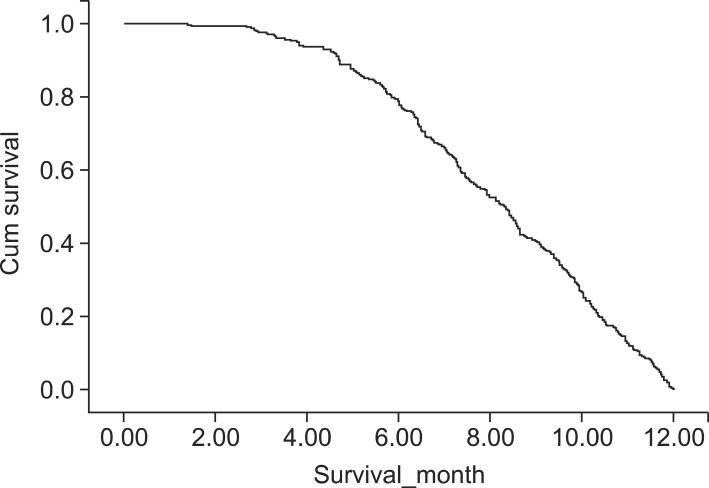

Among the 947 patients, 302 (31.9%) had early-mortality (died within 12 months after the surgery), including 235 (77.8%) who died between 6 and 12 months after surgery, which was at least three times of mortality occurred within 6-month after surgery (n=67: 22.2%, Fig. 2). Therefore, we analyzed the prognostic factors based on two time points, i.e., 6 and 12 months after surgery.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative survival curve of patients who died within 12 months after pancreatic resection (n=302) showing a more rapid downward pattern in the survival curve after 6 months.

Demographic features and univariate analysis of the prognostic factors associated with early mortality

In our study population, there were significantly more males (n=561: 59.2%) than females (n=386: 40.8%). The median patient age was 61 years (range, 22 to 86 years). Pancreaticoduodenectomy and pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in 494 (52.2%) of patients. Distal pancreatectomy and total pancreatectomy were performed in 230 (24.3%) and 219 (23.1%) patients, respectively. A total of 497 (52.5%) patients had pre-operative symptoms, including abdominal pain, backpain, indigestion, and body-weight loss.

Most study population was diagnosed with stage II (n=823: 87%) or Stage III (n=76: 8.0%) pancreatic cancer according to postoperative pathology examination. A total of 573 (60.5%) patients underwent adjuvant chemotherapy. However, 248 (26.2%) patients did not receive any antitumor therapy.

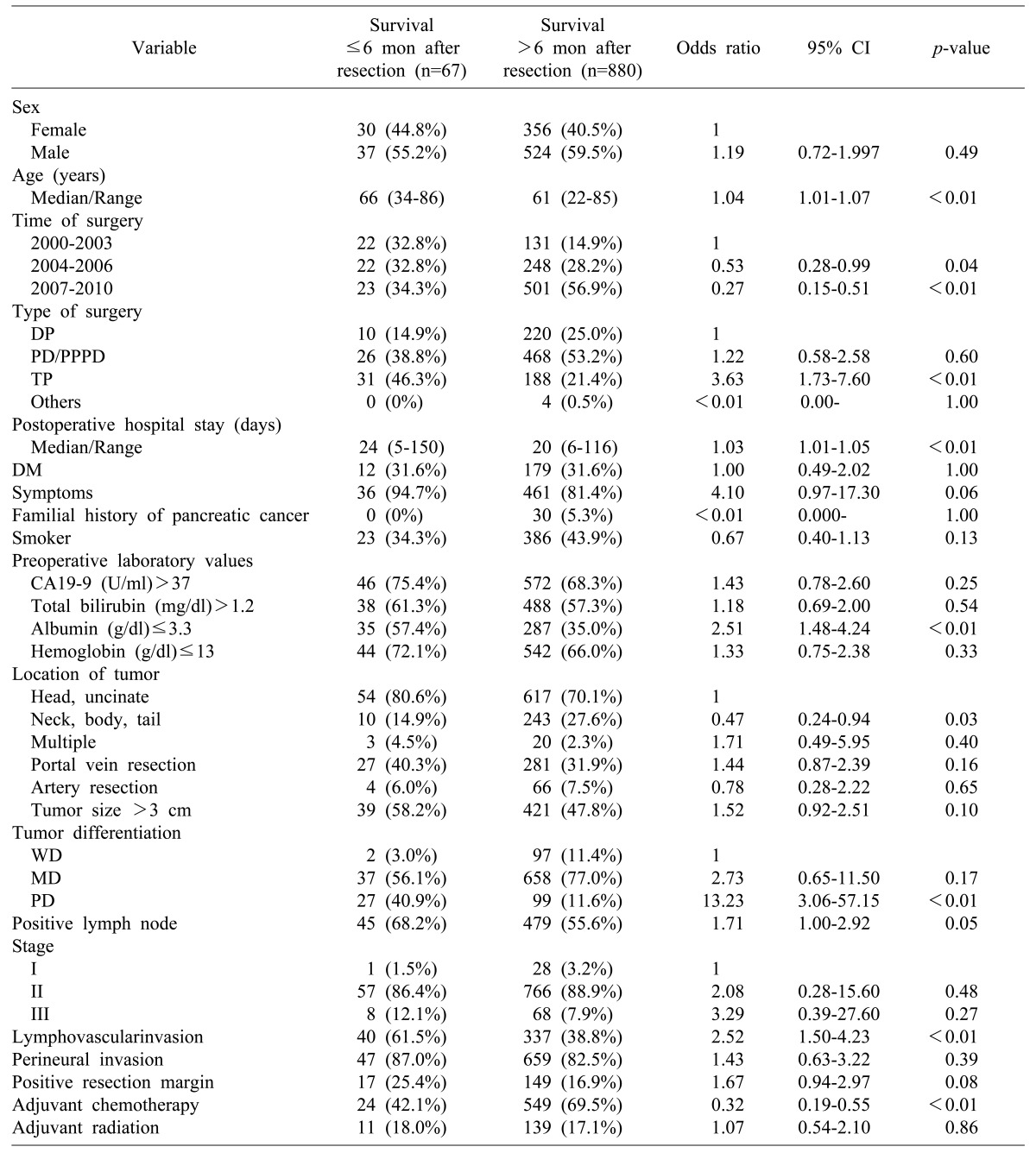

The pre-and postoperative characteristics and their association with early mortality within 6 months following surgery are summarized in Table 3. When the 6-month period was compared to 12 months after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the following was found to be associated with early mortality within 6 months after surgery: age, preoperative albumin≤3.3 g/dl, total pancreatectomy, the postoperative hospital stay, poorly differentiated tumor, and lymphovascular invasion. In addition to symptoms, the followings were also risk factors associated with early mortality during the first 12 months after surgery: preoperative CA19-9 >37 U/ml, preoperative hemoglobin ≤13 g/dl, portal vein resection, tumor size >3 cm, positive lymph node, stage III disease, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and positive resection margin.

Table 3.

Demographic features and univariate analysis of the prognostic factors associated with six-month early mortality after resection

Others include Hepatopancreato-duodenectomy, Median-saving pancreatectomy, Uncinate resection, Central pancreatectomy; Tumor staging according to the AJCC 7th edition staging guidelines. DP, distal pancreatectomy; PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; PPPD, pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy; TP, total pancreatectomy; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CI, confidence interval; DM, diabetes mellitus; WD, well-differentiated; MD, moderately differentiated; PD, poorly differentiated

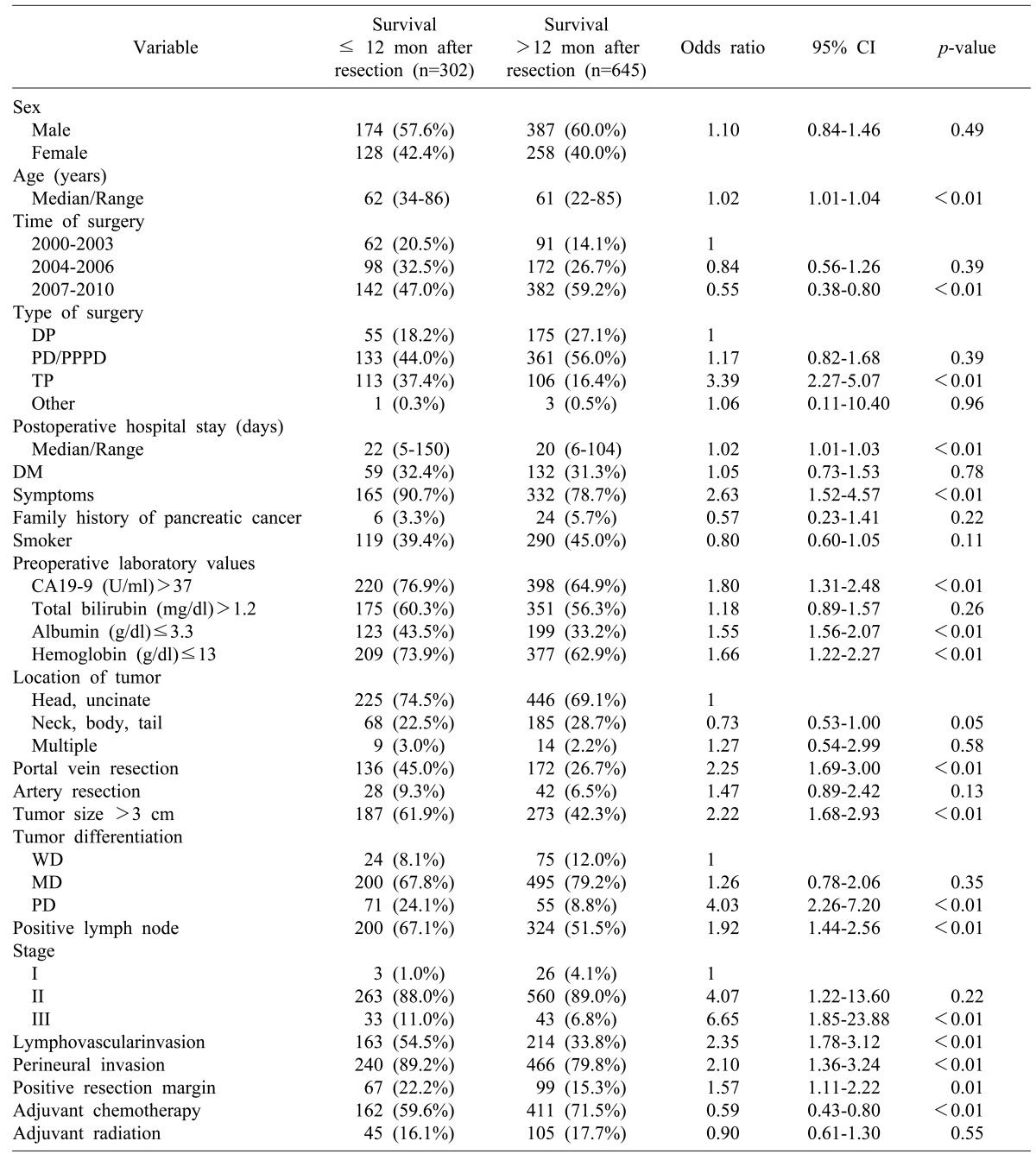

The time period of 2007-2010 during which surgery was performed and administration of adjuvant chemotherapy were both inversely associated with early mortality within 6 and 12 months after surgery. However, the time period of 2004-2006 and tumor located in the neck, body or tail were not related to early mortality within 12 months after surgery (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographic features and univariate analysis of the prognostic factors associated with 12 month, early mortality after resection

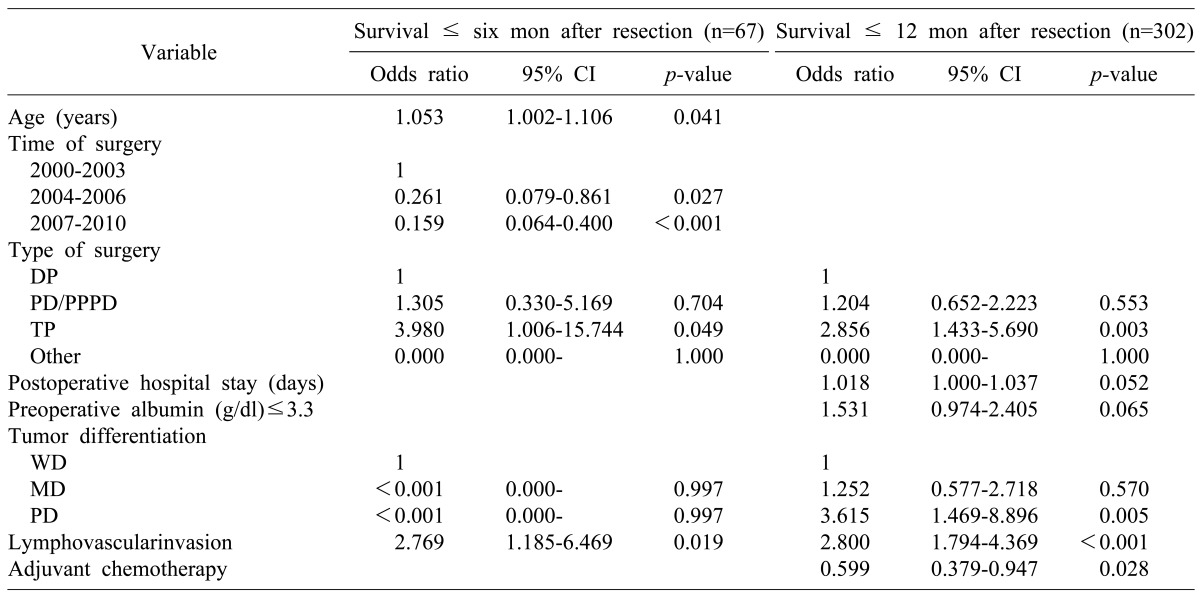

Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors associated with early mortality

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with significant predictors of survival in the univariate analysis. The multivariate analysis results showed a different pattern of risk factors associated mortality between the 6-month and 12-month periods after surgery. During the 6-month period, patient age and time of surgery were statistically significant (p<0.05) risk factors related to early mortality. On the contrary, poorly differentiated tumor and adjuvant chemotherapy were statistically significant (p<0.05) risk factors related to early mortality during the 12-month period. Total pancreatectomy and lymphovascular invasion were significant (p<0.05) prognostic factors of early mortality during both time periods (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors associated with six- and 12-month early mortality

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic cancer, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma, remains a lethal disease. Surgical resection is the only curative treatment for locally advanced disease. In general, the survival curve of malignant diseases with poor prognosis shows a rapid downward pattern during the early postoperative period, which is also the case in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Despite numerous studies and efforts over the last several decades, we did not note a dramatic improvement in pancreatic cancer survival rate.

Many pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients died during the early postoperative period despite curative resection. In our study, 67 (7.1%) and 302 (31.9%) patients died within 6 and 12 months following pancreatic resection, respectively. Other studies have shown similar outcomes, with up to 30% of patients died within 12 months after resection.12,13 If we can identify the risk factors related to early mortality after resection, we may be able to consider alternative treatment rather than up-front surgery in patients predicted to have a very high postoperative mortality rate. If we can correct the risk factors related to early mortality, we may be able to improve patient survival outcome related to early mortality and/or overall survival. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify the risk factors related to early mortality in patients undergoing pancreatic resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

In our study, 302 (31.9%) patients died within 12 months following their pancreatic surgery. Based on multivariate logistic regression analysis, patient age, time of surgery, total pancreatectomy, poorly differentiated tumor, lymphovascular invasion, and adjuvant chemotherapy were independent prognostic factors associated with early mortality within 6 and/or 12 months following their surgery. Multivariate analysis results showed a different pattern of risk factors associated with mortality between 6 and 12-month periods after surgery. During the six-month period, factors related to patient condition and the surgical technique (i.e., age and time of surgery) affected patient survival rate. On the other hand, within the 12-month period, factors related to the tumor biology (e.g. poorly differentiated tumor and adjuvant chemotherapy) affected early mortality.

Total pancreatectomy and lymphovascular invasion were significant prognostic factors of early mortality in both the 6- and 12-month periods after surgery. It is noteworthy that TNM staging, including positive lymph nodes and tumor size, were not associated with early mortality. In the 6- month period after resection, patient age was associated with increased risk of early mortality, suggesting that patient's general health condition and performance status may affect the mortality rate during the early postoperative period. On univariate analysis, a low preoperative albumin level (≤3.3 g/dl) was a risk factor related to possible 6- and 12-month early mortality (p<0.01), indicating that a patient's poor nutritional status might increase the early mortality rate following resection. In our study, C-reactive protein serum level was not examined. In several studies, the Glasgow prognostic score was proven to be a prognostic factor for pancreatic cancer.14,15,16 It will be useful to apply the Glasgow prognostic score system in future research regarding early mortality. According to time of surgery, the patient survival rate increased in 1, 2, 5 years and during the early postoperative period. This could be due to improvement in surgical techniques and perioperative management from accumulated surgical experience. Compared to other types of surgery, total pancreatectomy had a relatively high risk of early mortality within 6-month (OR, 3.980) and 12-month (OR, 2.856) following surgery. Many patients who underwent total pancreatectomy had much more difficulty controlling their blood sugar level, which could worsen their condition or performance. Therefore, early mortality in patients who underwent total pancreatectomy may be associated their poor general condition in addition to their disease severity. Poorly differentiated and undifferentiated carcinomas are known to be associated with poor outcome due to the high risk of hepatic metastases.17 In most patients, tumor differentiations were possible based on surgical specimens. Information regarding tumor differentiation obtained preoperatively can help determine the optimal treatment in a multidisciplinary setting, as routine sampling for resectable pancreatic cancer patients is debatable.18

In a study regarding early mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy or total pancreatectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, patient age, poorly differentiated tumor, and adjuvant chemoradiation therapy were statistically significant prognostic factors associated with early mortality defined as nine months after surgery.10 The duration of symptoms prior to surgery were shown to predict early mortality as determined in another study. However, such information was not available in our study.11

Recent reports have suggested that accurate patient selection based on reproducible prognostic factors and adjuvant chemoradiation therapies may have favorable impact on long-term patient survival.19,20 In the early mortality group after pancreatic resection, patient risk factor identification may increase the survival rate for the same reasons. To avoid early patient mortality following pancreatic resection, patients with multiple risk factors related to early mortality after pancreatectomy should be considered for alternative treatment. In particular, total pancreatectomy should be very carefully selected due to surgical risk and undetermined potential benefit. In addition, patient's general condition and surgical technique improvement are important. If necessary, more aggressive nutritional and general condition correction should be performed before surgery. Strategies to suppress tumor growth such as chemotherapy are also needed.

There are several limitations of this study. First, this was a retrospective analysis which had missing data and possible selection bias. The patient performance status and reasons for withholding adjuvant chemotherapy were difficult to be exactly determined based on medical records review. Second, it was difficult to accurately evaluate the cause of death if a patient died in a local hospital or at home.

There are only a few research studies describing early mortality after pancreatic resection for pancreatic cancer.10,11,12 To our knowledge, this study is the largest series regarding early mortality after pancreatic resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Further prospective studies will be needed in the future. Recently, laparoscopic pancreatectomy including robot-assisted pancreatectomy has been increasingly performed for pancreas cancer patients. In order to determine whether minimally invasive surgeries can decrease early mortality after pancreatectomy, more studies are needed.

In summary, pancreatic cancer including pancreatic adenocarcinoma remains a lethal disease, with a high early mortality rate after surgery up to 30% within 12 months following surgery. Early mortality after pancreatic resection is associated with factors other than TNM staging. To overcome early mortality after pancreatic resection, patients with multiple risk factors related to early mortality after pancreatectomy should be considered for alternative treatment. In particular, total pancreatectomy should be very carefully selected for patients with regard to the surgical risks and benefits. A patient's general condition and potential surgical technique improvement are important. If necessary, more aggressive nutritional and general condition correction should be performed before surgery. In addition, strategies to suppress the tumor such as chemotherapy are also necessary.

References

- 1.Kern S, Hruban R, Hollingsworth MA, Brand R, Adrian TE, Jaffee E, et al. A white paper: the product of a pancreas cancer think tank. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4923–4932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Ritchey J, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, et al. Validation of the 6th edition AJCC pancreatic cancer staging system: report from the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2007;110:738–744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumel H, Huguier M, Manderscheid JC, Fabre JM, Houry S, Fagot H. Results of resection for cancer of the exocrine pancreas: a study from the French Association of Surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81:102–107. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Koniaris L, Kaushal S, Abrams RA, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:567–579. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter A, Niedergethmann M, Sturm JW, Lorenz D, Post S, Trede M. Long-term results of partial pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head: 25-year experience. World J Surg. 2003;27:324–329. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6659-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton RR, Sarr MG, van Heerden JA, Colby TV. Carcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas: is curative resection justified? Surgery. 1992;111:489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan MF, Moccia RD, Klimstra D. Management of adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1996;223:506–511. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199605000-00006. discussion 511-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magistrelli P, Antinori A, Crucitti A, La Greca A, Masetti R, Coppola R, et al. Prognostic factors after surgical resection for pancreatic carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2000;74:36–40. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200005)74:1<36::aid-jso9>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu CC, Wolfgang CL, Laheru DA, Pawlik TM, Swartz MJ, Winter JM, et al. Early mortality risk score: identification of poor outcomes following upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:753–761. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1811-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barugola G, Partelli S, Marcucci S, Sartori N, Capelli P, Bassi C, et al. Resectable pancreatic cancer: who really benefits from resection? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3316–3322. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takamori H, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, Tsuji T, Hamada C, Baba H. Identification of prognostic factors associated with early mortality after surgical resection for pancreatic cancer: under-analysis of cumulative survival curve. World J Surg. 2006;30:213–218. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy EP, Yeo CJ. The case for routine use of adjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:597–603. doi: 10.1002/jso.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polterauer S, Grimm C, Seebacher V, Rahhal J, Tempfer C, Reinthaller A, et al. The inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score predicts survival in patients with cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:1052–1057. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181e64bb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimoda M, Katoh M, Kita J, Sawada T, Kubota K. The Glasgow prognostic score is a good predictor of treatment outcome in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Chemotherapy. 2010;56:501–506. doi: 10.1159/000321014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin HL, Ohara K, Kiberu A, Van Hagen T, Davidson A, Khattak MA. Prognostic value of systemic inflammation-based markers in advanced pancreatic cancer. Intern Med J. 2014;44:676–682. doi: 10.1111/imj.12453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibata K, Matsumoto T, Yada K, Sasaki A, Ohta M, Kitano S. Factors predicting recurrence after resection of pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Pancreas. 2005;31:69–73. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000166998.04266.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callery MP, Chang KJ, Fishman EK, Talamonti MS, William Traverso L, Linehan DC. Pretreatment assessment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1727–1733. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitz FR, Abbruzzese JL, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Lowy AM, Fenoglio CJ, et al. Preoperative and postoperative chemoradiation strategies in patients treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:928–937. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller AR, Robinson EK, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Chiao PJ, Lenzi RL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1998;7:183–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]