Abstract

Topoisomerases and histone deacetylases (HDACs) are considered as important therapeutic targets for a wide range of cancers, due to their association with the initiation, proliferation and survival of cancer cells. Topoisomerases are involved in the cleavage and religation processes of DNA, while HDACs regulate a dynamic epigenetic modification of the lysine amino acid on various proteins. Extensive studies have been undertaken to discover small molecule inhibitor of each protein and thereby, several drugs have been transpired from this effort and successfully approved for clinical use. However, the inherent heterogeneity and multiple genetic abnormalities of cancers challenge the clinical application of these single targeted drugs. In order to overcome the limitations of a single target approach, a novel approach, simultaneously targeting topoisomerases and HDACs with a single molecule has been recently employed and attracted much attention of medicinal chemists in drug discovery. This review highlights the current studies on the discovery of dual inhibitors against topoisomerases and HDACs, provides their pharmacological aspects and advantages, and discusses the challenges and promise of the dual inhibitors.

Keywords: Dual inhibitor, Topoisomerase, Histone deacetylases, Small molecule

INTRODUCTION

Drug design is the inventive process of finding new medications based on the knowledge of a biological target. Conventional drug design embraces the notion of ‘one target, one drug, one disease’ and it has been prevalent paradigm in pharmaceutical industry over the past two decades.1 The main idea of this approach is that discovery of a biologically relevant single protein and subsequently, modulation of its function will provide a therapeutic strategy. In cancer research, this approach has brought about several targeted drugs such as Gleevec (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), Iressa (AstraZeneca, London, UK) and Herceptin (Genetech, South San Francisco, CA, USA). These highly selective drugs seemed to successfully eradicate tumors in more specific ways and reduce unwanted side effects without hitting secondary nontherapeutic targets. Despite their superiority in the therapeutic efficacy and selectivity, the inhibition of a single target often falls short of producing the desired therapeutic effect.2 Cancers are heterogeneous and mostly driven by multiple genetic abnormalities. Accordingly, simultaneous intervention of two or multiple targets is inevitably necessary in the fight against malignant cancers.3,4 Nevertheless, to design drugs capable of inhibiting multiple targets is a great challenge for medicinal chemists.

One way to achieve the simultaneous blockage of two or multiple targets is combination chemotherapy. Combination chemotherapy is a therapeutic intervention to administer two or more drugs to the patients, and often creates synergistic anticancer effects by blocking the key signaling network as well as viable compensatory pathways.5,6 However, two or more separate drugs very likely have different pharmacokinetic profiles such as half-lives, distributions, and metabolic stabilities, and more importantly combination chemotherapy may introduce adverse drug-drug interactions to furnish unwanted side effects.7,8 These complex factors have hampered broad clinical applications of combination chemotherapy for the treatment of cancers. As an alternative strategy to overcome these limitations, drug design to hit multiple targets with a single molecule has attracted the attention of medicinal chemists in drug discovery.4 To this end, a novel approach has been recently employed to discover multi-target drugs, which simultaneously inhibit two or more enzymes. Topoisomerases including topoisomerase I and II are a family of enzymes manipulate DNA topology, such as knots and tangles, remaining on DNA after replication and transcription.9,10 More intriguingly, topoisomerases are expressed at higher levels in growing cells than quiescent cells.11 In contrast, histone deacetylases (HDACs) are a class of epigenetic enzymes that cleave acetyl groups from N-acetyl lysine on proteins including histone, p53, E2F, α-tubulin, and Hsp90.12–16 HDACs regulate the expression and activity of numerous proteins that are involved in the proliferation and survival of cancer cells. Therefore, the potential therapeutic benefits associated to topoisomerases and HDACs emphasize the importance of identifying dual inhibitors of these enzymes. In this review, we will focus on the current studies on small molecule inhibitors simultaneously inhibiting the functions of topoisomerases and HDACs, provide their pharmacological background and advantages, and discuss the challenges and promise of the dual inhibitors.

MAIN SUBJECT

1. Topoisomerase I and II

In human, the entire genome of a single cell needs to be squeezed into 2- to 10-μm diameter of a tiny nucleus.10 To maintain this DNA compaction, enzymes capable of managing superhelical tension and knots are necessarily required. Topoisomerases, including topoisomerase I and II, are ubiquitous enzymes that control DNA supercoiling and entanglements (Fig. 1).9,10 The opening of double-stranded DNA and separation of these two strands during transcription and replication produce positive (left-handed) and negative (right-handed) supercoiling on either side of open DNA segment. Positive supercoiling and consequent tightening of DNA prevent separation of its two strands, and further impair the polymerization of DNA. Therefore, without topoisomerases, excessive positive supercoiling and entanglements of DNA eventually stall transcription and replication. Topoisomerase I relieves the torsional strain on DNA during DNA replication by cleaving one stand of a DNA double helix and passing one strand over the other, while topoisomerase II removes knots and tangles by generating transient double-stranded breaks in the double helix (Fig. 1).17–20 Cleavage of DNA occurs by transesterification reactions, in which an active tyrosine residue of topoisomerases attacks the phosphodiester linkages of DNA to form tyrosyl-DNA covalent bonds at the end of the break (Fig. 1B and 1E). Topoisomerase I breaks DNA by forming a tyrosyl-DNA covalent bond at the 3’ end of the break, whereas topoisomerase II cuts DNA by covalent attachment to the 5’ end of the break. Under normal conditions, topoisomerases process the cleaving and religating reactions very rapidly, in that the religation reactions occur faster than cleavage reactions, thereby the complexes of topoisomerases-DNA are considered transient. A number of topoisomerase inhibitors have been proven to exhibit anticancer effects by stabilizing the complexes of topoisomerases-DNA through specifically binding at the interface of topoisomerases-DNA complexes (Fig. 1C and 1F). Inhibitors of topoisomerase I stabilize topoisomerase I and DNA cleavage complexes, prevent the religation of DNA, and induce lethal DNA strand breaks. Inhibitors of topoisomerase I are commonly used to treat several cancers including ovarian, lung, breast, colon and cervical cancer. In contrast, inhibitors of topoisomerase II trap topoisomerase II and DNA cleavage complexes, and are used for lymphoma, leukemia, testicular, and lung cancer.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of topoisomerase I (TopI, left) and II (TopII, right). (A) Noncovalent binding of TopI and (D) TopII to DNA. Under normal conditions, TopI and TopII cleave and religate DNA and religation is a faster process than cleavage, so cleavage complexes are transient intermediates. The arrow indicates the reversible ligation and cleavage reaction under normal condition (A, B for TopI and D, E for TopII). (C) Trapping the cleavage complexes of DNA-topoisomerases by TopI inhibitors and (F) TopII inhibitors promotes DNA damages.

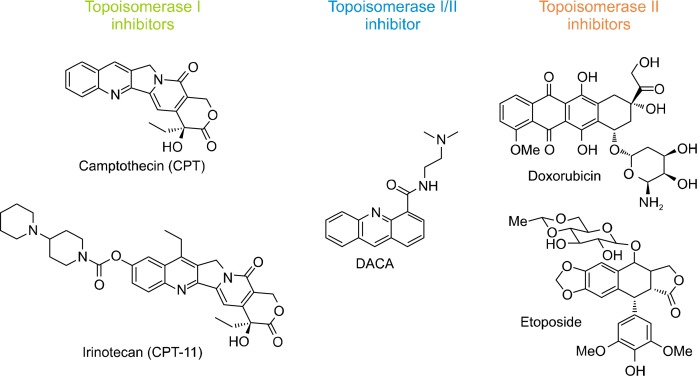

Camptothecin (CPT) was first isolated from the Chinese tree Camptotheca acuminate (Fig. 2).21–23 In 1966, drug screening by National Cancer Institute discovered that CPT displayed a marked anticancer activity.23 However, its clinical development was discontinued in the early 1970s, due to the appearance of unacceptable side effects. In 1985 Hsiang et al.24 identified DNA topoisomerase I as the molecular target of CPT that initiated the development of CPT derivatives to obtain clinically applicable anticancer drugs. The extensive studies and efforts introduced a water-soluble CPT derivative, irinotecan (CPT-11), which was approved for clinical use in 1996, more than thirty years after the first isolation of the natural alkaloid CPT.25,26 The main clinical use of irinotecan is for the treatment of colorectal cancer for both first and second line therapy, and irinotecan has also shown clinical activity against lung, gastric, cervical and ovarian cancers, malignant lymphoma and other malignancies.25,27–29

Figure 2.

Representative structures of topoisomerase I/II inhibitors. DACA, [2-dimethylamino]ethyl]acridine-4-carboxamide.

Inhibitors of topoisomerase II, including doxorubincin and etoposide represent some of the most successful and widely prescribed anticancer drugs worldwide.30,31 Up to date, six of topoisomerase II inhibitors have been approved for clinical use. Doxorubicin is a cytotoxic anthracycline antibiotic isolated from cultures of Streptomyces peucetius var. caesius and its clinical application includes a variety of solid tumors and hematologic cancers.30 Since the introduction of etoposide in 1971, this topoisomerase II inhibitor constitutes an essential and standard part of chemotherapy for a number of cancers, notably in small cell lung cancer (SCLC), ovarian, testicular cancer, lymphoma, and acute myeloid leukemia.32–34 Like doxorubicin, etoposide was clinically developed and approved without knowing that topoisomerase II was its molecular target. Etoposide is now commonly used in combination of other anticancer drugs, and proven to be particularly efficient against germinal-cell cancer and SCLC.31

[2-dimethylamino]ethyl]acridine-4-carboxamide (DACA) is an acridine-4-carboxamide cytotoxic drugs that bind to DNA by intercalation, acts as a dual inhibitor of both topoisomerase I and II, and stimulates DNA cleavage.35 The 4-carboxamide chain of DACA is significantly important to reinforce drug-DNA interaction and to penetrate into cells, furnishing a high DNA damage and cytotoxicity.36

Overall, topoisomerase inhibitors play a critical role in transcription and replication, induce enzyme-mediated DNA damage, and ultimately lead to cancer cell death. Although this class of inhibitors are among the most effective and most commonly used anticancer drugs, the emergence of drug resistance often hampers their clinical efficacy for the treatment of cancers.37–39

2. Histone deacetylases

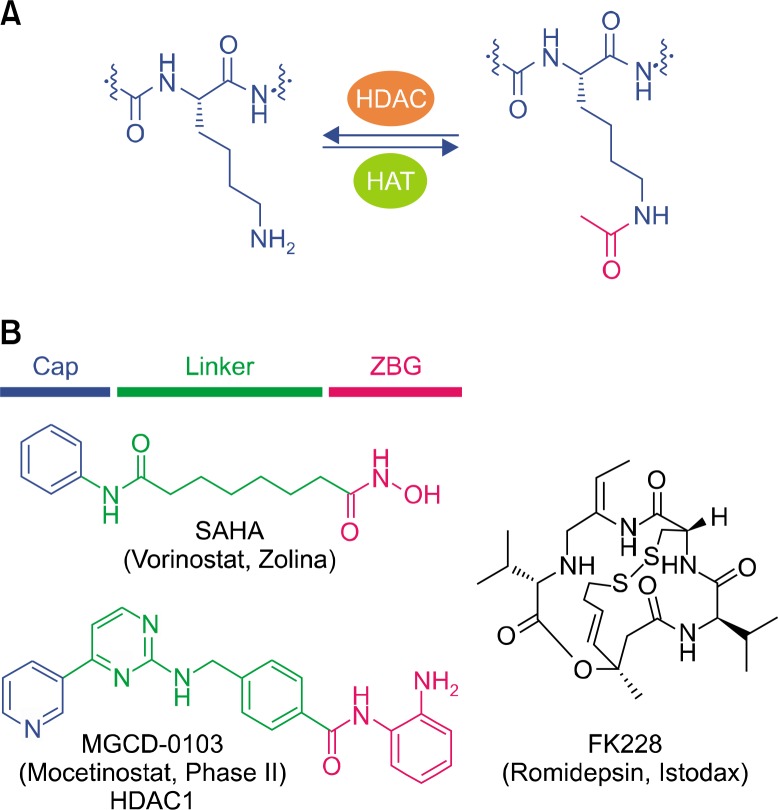

HDACs are a class of epigenetic enzymes which remove acetyl groups from N-acetyl lysine amino acids on histones, allowing histones to wrap DNA tightly (Fig. 3A).40–43 There are eleven zinc-dependent HDAC isoforms which can be classified into three classes depending on their sequence homology. Class I comprises HDAC 1, 2, 3, and 8, localized to the nucleus and class II a/b consists of HDAC 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10 found in the nucleus and cytoplasm. HDAC11 is a sole member of class IV and shares sequence similarity to classes I and II. Additionally, zinc-independent seven isoforms, Sirt1-7 are referred to as class III, which utilize NAD+ as a cofactor as opposed to zinc. HDACs along with histone acetyltransferases (HATs) are important classes of enzymes which regulate a dynamic post-translational modification of the lysine by acetylating and de-acetylating ε-amino group of the residue on proteins including histones. HDACs function was originally discovered to remove acetyl groups from histone proteins, leading to a condensed structure and transcriptional suppression, while histone acetylation by HATs results in a relaxed chromatin structure that is associated with the transcriptional upregulation. Interestingly, recent evidence has illustrated that HDACs are involved in the deacetylation of important non-histone regulatory proteins such as p53, E2F, α-tubulin, and Hsp90.12–16 Collectively, inhibition of HDACs enzymatic activity can induce growth arrest and apoptosis in tumor cells. Therefore, HDACs have emerged as novel therapeutic targets for cancer treatment, and thereby two broad spectrum HDAC inhibitors, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) and FK228 have been approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.44–46

Figure 3.

Post-translational modification of the lysine ε-amino group and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. (A) Acetylation and de-acetylation of the lysine ε-amino group are mediated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and HDACs, respectively. (B) Pharmacophore model of HDAC inhibitors and their representative structures. SAHA, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid; ZBG, zinc binding group.

HDAC inhibitors have stimulated much enthusiasm in oncology research and numerous distinct classes of HDAC inhibitors have been evaluated in clinical trials.43,47 Intriguingly, most of the zinc-dependent HDAC inhibitors share common pharmacophore model, which consist of three domains, capping group, linker, and zinc binding group (ZBG) shown in Figure 3B. Capping group is a surface recognition unit and usually contains a hydrophobic and aromatic moiety to interact with the rim of the binding pocket. Linker domain is designed to connect the cap group to ZBG as a saturated or unsaturated structure. ZBG coordinates to Zn2+ ion at the bottom of the active site, which includes the hydroxamic acid, carboxylic acid, and o-aminoanilide moiety.

3. Dual inhibitors targeting topoisomerases and histone deacetylases

Numerous studies have suggested that dual inhibition of HDACs and topoisomerases induces synergistic effect on impairing cell proliferation and triggering apoptotic cell death. Moreover, HDAC inhibitors are recognized as ‘sensitizing drugs’ that manifest synergistic efficacy with other anticancer drugs, and more interestingly their nature of chemical flexibility, readily embedding other drugs to the structure of HDAC inhibitors facilitates medicinal chemists to embark the journey toward the dual inhibitor discovery.48–53 While single targeted drugs against either HDACs or topoisomerases still remain a popular design endpoint, there has been a recent surge of interest toward dual inhibitor design against HDACs and topoisomerases. Importantly, both HDACs and topoisomerases are mostly localized to the nucleus, thereby the opportunity for dual inhibition of both enzymes by a single drug is substantially high. Fueled by significant synergistic effects and pharmacokinetic advantages, a number of studies have been reported to discover dual inhibitors simultaneously targeting HDACs and topoisomerases.54–58

In 2012, Guerrant et al.54 for the first time introduced dual inhibitors targeting HDACs and topoisomerase II. In this study, they covalently combined HDAC inhibitor, SAHA with topoisomerase II inhibitor, daunorubicin to furnish a novel dual acting agent, 1 in Figure 4.54 Compound 1 potently inhibited the proliferation of cancer cells, including DU-145, SK-MES-1, and MCF-7. Interestingly, compound 1 displayed substantially high anti-proliferative activity (IC50 = 0.13 μM) against DU-145, prostate carcinoma cell line. As expected, the study of molecular mechanism illustrated that compound 1 presented both HDAC and topoisomerase II inhibition signatures under cell-free condition and in vitro cell cultures.

Figure 4.

Pharmacophoric features of dual inhibitors against histone deacetylases and topoisomerases and their chemical structures. ZBG, zinc binding group.

In 2013, the same research group reported another dual acting inhibitor 2 as a follow-up to their previous study.55 In contrast to the previous study, they designed HDAC-topoisomerase I inhibitor by covalently merging SAHA-like HDAC inhibitor to the comptothecin framework. Compound 2 efficiently impaired the growth of HeLa (IC50 = 0.12 nM) along with DU-145 cell line (IC50 = 2.05 μM), and furnished very potent inhibitory activity against HDAC1 (IC50 = 129 nM) and HDAC6 (IC50 = 42 nM). Nonetheless, Guerrant et al.54,55 had performed a pioneering work on the discovery of dual HDAC-topoisomerases inhibitors, and compound 1 and 2 provided promise as potent anticancer drugs with the potential to broadly arrest tumor growth by inhibiting two essential enzymes.

In 2013, Zhang et al.56 reported a novel podophyllotoxin derivative, 3 as a dual inhibitor against HDAC and topoisomerase II. In their study, they systematically varied aromatic capping group connection, linker length, and zinc-binding group to clarify structure-activity relationships. Among a series of hybrid inhibitors they synthesized, compound 3 displayed the best HDAC inhibitory activity against HDAC1 (IC50 = 11 nM), HDAC3 (IC50 = 9.6 nM) and HDAC6 (IC50 = 5.6 nM), which was 10 to 20 fold more potent than Food and Drug Administration-approved panHDAC inhibitor, SAHA. Compound 3 also demonstrated significant anti-proliferative activity towards the HCT116 cell line at micromolar concentration (IC50 = 3.33 μM). Interestingly, the introduction of anilides as ZBG resulted in increased anti-proliferative activity against HCT116 and A549 cells to indicate that the ZBG played a critical role in the efficacy of the compound.

In 2014, Yu et al.57 introduced a small molecule hybrid 4 (WJ35435) by connecting HDAC inhibitor SAHA to topoisomerase inhibitor DACA. Compound 4 displayed a better activity than SAHA and DACA against human hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancers (HRMPCs) cell lines PC-3 (IC50 = 0.31 μM) and DU-145 (IC50 = 0.16 μM), and importantly compound 4 exhibited good selectivity for malignant over benign prostate cancers. In vitro enzyme assay and cell-based assay showed that compound 4 was a potent HDAC inhibitor, more specifically against HDAC1 (IC50 = 16.6 nM) and HDAC6 (IC50 = 2.2 nM) in nanomolar potency. As designed, compound 4 induced anti-HDAC and anti-topoisomerase I activities, caused profound DNA damage, and arrested cell cycle at G1 and G2 phases. Consequently, compound 4 resulted in the inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in HRMPCs

He et al.58 recently reported a first in class triple HDAC/TopI/TopII inhibitor, 5. They rationally designed a series of novel hybrids on the basis of 3-amino-10-hydroxyevodiamine and SAHA. Using a molecular hybridization strategy, they attached HDAC inhibitor, SAHA to topoisomerase I and II inhibitor, 3-amino-10-hydroxyevodiamine to furnish compound 5. Compound 5 exhibited excellent anti-proliferative activities against MDA-MB (IC50 = 2.3 μM), HCT116 (IC50 = 0.41 μM), and HLF (IC50 = 1.3 μM) cell lines, and provided good anti-HDAC inhibitory activities against HDAC1 (IC50 = 24 nM), HDAC6 (IC50 = 13 nM), and HDAC8 (IC50 = 2.5 μM). Notably, studies on the mechanism of action proved that compound 5 simultaneously inhibited topoisomerase I, II and HDACs. Taken together, the study provided a proof of concept study for the discovery of triple HDAC/TopI/TopII inhibitors.

CONCLUSION

Topoisomerases are ubiquitous enzymes that process the cleavage and religation reactions to manage DNA supercoiling and entanglements. Since topoisomerases play an important role in transcription and DNA replication, intervention of the enzyme ultimately leads to cancer cell death. Likewise, HDACs are an important class of enzymes that are also considered as promising therapeutic targets for the treatment of cancer. HDACs regulate a dynamic epigenetic modification of the lysine on various proteins including histones, p53, E2F, α-tubulin, and Hsp90. Inhibition of HDACs can impair the growth of cancer cell and induce the apoptotic cell death of cancer. Therefore, extensive studies on introducing HDACs or topoisomerases inhibitors have been undertaken in the last two decades. By taking advantage of their substantial synergistic effects, a number of inhibitors targeting both enzymes have been recently reported and presented great promise as novel anticancer drugs. Despite their great promise in the clinical application, any potential risk of side effects should not be neglected. The dual inhibitors are often characterized by high molecular weight that might reduce the chances of their druggabilities. Therefore, the safety profiles as well as pharmacokinetic properties need to be thoroughly considered in the design of dual inhibitors. In this review, we overviewed current studies on dual inhibitors specifically targeting topoisomerases and HDACs, provided pharmacological insights and advantages, and discussed their therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0023605).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal S. Targeted cancer therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:427–8. doi: 10.1038/nrd3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown D, Superti-Furga G. Rediscovering the sweet spot in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:1067–77. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02902-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boran AD, Iyengar R. Systems approaches to polypharmacology and drug discovery. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2010;13:297–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrelli A, Giordano S. From single- to multi-target drugs in cancer therapy: when aspecificity becomes an advantage. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:422–32. doi: 10.2174/092986708783503212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bevins RL, Zimmer SG. It’s about time: scheduling alters effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors on camptothecin-treated cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6957–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MS, Blake M, Baek JH, Kohlhagen G, Pommier Y, Carrier F. Inhibition of histone deacetylase increases cytotoxicity to anticancer drugs targeting DNA. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morphy R, Kay C, Rankovic Z. From magic bullets to designed multiple ligands. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:641–51. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morphy R, Rankovic Z. Designed multiple ligands. An emerging drug discovery paradigm. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6523–43. doi: 10.1021/jm058225d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pommier Y. Drugging topoisomerases: lessons and challenges. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:82–95. doi: 10.1021/cb300648v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pommier Y, Leo E, Zhang H, Marchand C. DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial drugs. Chem Biol. 2010;17:421–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsiang YH, Wu HY, Liu LF. Topoisomerases: novel therapeutic targets in cancer chemotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:1801–2. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu W, Roeder RG. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell. 1997;90:595–606. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, et al. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature. 2002;417:455–8. doi: 10.1038/417455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovacs JJ, Murphy PJ, Gaillard S, Zhao X, Wu JT, Nicchitta CV, et al. HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell. 2005;18:601–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez-Balbás MA, Bauer UM, Nielsen SJ, Brehm A, Kouzarides T. Regulation of E2F1 activity by acetylation. EMBO J. 2000;19:662–71. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marzio G, Wagener C, Gutierrez MI, Cartwright P, Helin K, Giacca M. E2F family members are differentially regulated by reversible acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10887–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deweese JE, Osheroff N. The DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase II: wolf in sheep’s clothing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:738–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nitiss JL. DNA topoisomerase II and its growing repertoire of biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:327–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Champoux JJ. DNA topoisomerase I-mediated nicking of circular duplex DNA. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;95:81–7. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-057-8:81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JC. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:665–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.003313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wall ME. Camptothecin and taxol: discovery to clinic. Med Res Rev. 1998;18:299–314. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(199809)18:5<299::AID-MED2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wall ME, Wani MC. Camptothecin and taxol: discovery to clinic--thirteenth Bruce F. Cain memorial award lecture. Cancer Res. 1995;55:753–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wall ME, Wani MC, Cook CE, Palmer KH, McPhail AT, Sim GA. Plant antitumor agents. I. The isolation and structure of camptothecin, a novel alkaloidal leukemia and tumor inhibitor from Camptotheca acuminata. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:3888–90. doi: 10.1021/ja00968a057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsiang YH, Hertzberg R, Hecht S, Liu LF. Camptothecin induces protein-linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14873–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FDA approves irinotecan as first-line therapy for colorectal cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000;14:652, 654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potmesil M. Camptothecins: from bench research to hospital wards. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1431–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohno R, Okada K, Masaoka T, Kuramoto A, Arima T, Yoshida Y, et al. An early phase II study of CPT-11: a new derivative of camptothecin, for the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1907–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.11.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuoka M, Niitani H, Suzuki A, Motomiya M, Hasegawa K, Nishiwaki Y, et al. A phase II study of CPT-11, a new derivative of camptothecin, for previously untreated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:16–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada Y, Yoshino M, Wakui A, Nakao I, Futatsuki K, Sakata Y, et al. Phase II study of CPT-11, a new camptothecin derivative, in metastatic colorectal cancer. CPT-11 Gastrointestinal Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:909–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailly C. Contemporary challenges in the design of topoisomerase II inhibitors for cancer chemotherapy. Chem Rev. 2012;112:3611–40. doi: 10.1021/cr200325f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meresse P, Dechaux E, Monneret C, Bertounesque E. Etoposide: discovery and medicinal chemistry. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2443–66. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Dwyer PJ, Leyland-Jones B, Alonso MT, Marsoni S, Wittes RE. Etoposide (VP-16-213). Current status of an active anticancer drug. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:692–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198503143121106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henwood JM, Brogden RN. Etoposide. A review of its pharmaco-dynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in combination chemotherapy of cancer. Drugs. 1990;39:438–90. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199039030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belani CP, Doyle LA, Aisner J. Etoposide: current status and future perspectives in the management of malignant neoplasms. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1994;34(Suppl):S118–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00684875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atwell GJ, Rewcastle GW, Baguley BC, Denny WA. Potential anti-tumor agents. 50. In vivo solid-tumor activity of derivatives of N-[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]acridine-4-carboxamide. J Med Chem. 1987;30:664–9. doi: 10.1021/jm00387a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailly C, Denny WA, Mellor LE, Wakelin LP, Waring MJ. Sequence specificity of the binding of 9-aminoacridine- and amsacrine-4-carboxamides to DNA studied by DNase I footprinting. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3514–24. doi: 10.1021/bi00128a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen AY, Liu LF. Mechanisms of resistance to topoisomerase inhibitors. Cancer Treat Res. 1994;73:263–81. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2632-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alagoz M, Gilbert DC, El-Khamisy S, Chalmers AJ. DNA repair and resistance to topoisomerase I inhibitors: mechanisms, biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:3874–85. doi: 10.2174/092986712802002590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilati P, Nitti D, Mocellin S. Cancer resistance to type II topoisomerase inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:3900–6. doi: 10.2174/092986712802002473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marks P, Rifkind RA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Miller T, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylases and cancer: causes and therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:194–202. doi: 10.1038/35106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marks PA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Rifkind RA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors as new cancer drugs. Curr Opin Oncol. 2001;13:477–83. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meinke PT, Liberator P. Histone deacetylase: a target for anti-proliferative and antiprotozoal agents. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:211–35. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly WK, O’Connor OA, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: from target to clinical trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11:1695–713. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.12.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mann BS, Johnson JR, Cohen MH, Justice R, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: vorinostat for treatment of advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:1247–52. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-10-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant C, Rahman F, Piekarz R, Peer C, Frye R, Robey RW, et al. Romidepsin: a new therapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and a potential therapy for solid tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2010;10:997–1008. doi: 10.1586/era.10.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mwakwari SC, Patil V, Guerrant W, Oyelere AK. Macrocyclic histone deacetylase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:1423–40. doi: 10.2174/156802610792232079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller TA, Witter DJ, Belvedere S. Histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:5097–116. doi: 10.1021/jm0303094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamblin M, Dabbas B, Spingarn R, Mendoza-Sanchez R, Wang TT, An BS, et al. Vitamin D receptor agonist/histone deacetylase inhibitor molecular hybrids. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:4119–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saijo K, Katoh T, Shimodaira H, Oda A, Takahashi O, Ishioka C. Romidepsin (FK228) and its analogs directly inhibit phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity and potently induce apoptosis as histone deacetylase/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dual inhibitors. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1994–2001. doi: 10.1111/cas.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gryder BE, Akbashev MJ, Rood MK, Raftery ED, Meyers WM, Dillard P, et al. Selectively targeting prostate cancer with anti-androgen equipped histone deacetylase inhibitors. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:2550–60. doi: 10.1021/cb400542w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gryder BE, Rood MK, Johnson KA, Patil V, Raftery ED, Yao LP, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors equipped with estrogen receptor modulation activity. J Med Chem. 2013;56:5782–96. doi: 10.1021/jm400467w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ko KS, Steffey ME, Brandvold KR, Soellner MB. Development of a chimeric c-Src kinase and HDAC inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:779–83. doi: 10.1021/ml400175d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griffith D, Morgan MP, Marmion CJ. A novel anti-cancer bifunctional platinum drug candidate with dual DNA binding and histone deacetylase inhibitory activity. Chem Commun (Camb) 2009;44:6735–7. doi: 10.1039/b916715c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guerrant W, Patil V, Canzoneri JC, Oyelere AK. Dual targeting of histone deacetylase and topoisomerase II with novel bifunctional inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1465–77. doi: 10.1021/jm200799p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guerrant W, Patil V, Canzoneri JC, Yao LP, Hood R, Oyelere AK. Dual-acting histone deacetylase-topoisomerase I inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:3283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X, Bao B, Yu X, Tong L, Luo Y, Huang Q, et al. The discovery and optimization of novel dual inhibitors of topoisomerase II and histone deacetylase. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:6981–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu CC, Pan SL, Chao SW, Liu SP, Hsu JL, Yang YC, et al. A novel small molecule hybrid of vorinostat and DACA displays anticancer activity against human hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer through dual inhibition of histone deacetylase and topoisomerase I. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;90:320–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He S, Dong G, Wang Z, Chen W, Huang Y, Li Z, et al. Discovery of novel multiacting topoisomerase I/II and histone deacetylase inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:239–43. doi: 10.1021/ml500327q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]