Abstract

Dietary nitrate and nitrite are sources of gastric NO, which modulates blood flow, mucus production, and microbial flora. However, the intake and importance of these anions in infants is largely unknown. Nitrate and nitrite levels were measured in breast milk of mothers of preterm and term infants, infant formulas, and parenteral nutrition. Nitrite metabolism in breast milk was measured after freeze-thawing, at different temperatures, varying oxygen tensions, and after inhibition of potential nitrite-metabolizing enzymes. Nitrite concentrations averaged 0.07 ± 0.01 μM in milk of mothers of preterm infants, less than that of term infants (0.13 ± 0.02 μM) (P < .01). Nitrate concentrations averaged 13.6 ± 3.7 μM and 12.7 ± 4.9 μM, respectively. Nitrite and nitrate concentrations in infant formulas varied from undetectable to many-fold more than breast milk. Concentrations in parenteral nutrition were equivalent to or lower than those of breast milk. Freeze-thawing decreased nitrite concentration ∼64%, falling with a half-life of 32 minutes at 37°C. The disappearance of nitrite was oxygen-dependent and prevented by ferricyanide and 3 inhibitors of lactoperoxidase. Nitrite concentrations in breast milk decrease with storage and freeze-thawing, a decline likely mediated by lactoperoxidase. Compared to adults, infants ingest relatively little nitrite and nitrate, which may be of importance in the modulation of blood flow and the bacterial flora of the infant GI tract, especially given the protective effects of swallowed nitrite.

Keywords: human milk, nitric oxide, lactoperoxidase, nitrite oxidation, newborn infants, dietary nitrate, dietary nitrite, parenteral nutrition

Introduction

Since being established as a potent vasodilator, nitric oxide (NO) has been one of the most intensely studied compounds in biology and is now considered to be an essential signaling molecule in a diverse set of pathways. Endogenous NO is produced predominantly through the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline by NO synthase enzymes. Through reactions with metal-containing proteins and oxygen, endogenous NO is rapidly oxidized to nitrite (NO2-) and nitrate (NO3-). Although these anions were once thought to be inert at physiological concentrations, more recent evidence indicates that nitrite plays a significant role in cardiovascular homeostasis1 and protects against hypoxic and ischemic stress in the brain,2,3 heart,4,5 lungs,6 and kidney.7 Thus, there is growing interest in factors that contribute to the concentrations of nitrite in the body.

A large portion of plasma nitrite is derived from the oxidation of NO produced by endothelial NO synthases.8 However, plasma nitrite concentrations are also influenced by the ingestion of nitrite and nitrate, the latter being converted to nitrite in the mouth by commensal bacteria present on the dorsal surface of the tongue.9 The oral conversion of nitrate to nitrite is enhanced by active secretion of nitrate from the blood into the saliva. Once swallowed, the salivary nitrite can contribute to plasma nitrite concentrations,10 or it can be protonated to nitrous acid resulting in a cascade of reactions leading to several bioactive products including nitrotyrosines, nitrosothiols, and nitrated lipids (see review by Rocha et al11). Although the chemistry of nitrite in the acidic gastric milieu is not fully characterized, it likely plays a role in the observed effects of ingested nitrite in the adult rat. These include increased gastric blood flow12,13 and mucus production13 and protection against ulcers.12,14

In the newborn period, breast milk and artificial breast milk substitutes (referred to herein as “infant formulas”) are the sole dietary sources of nitrate and nitrite. The nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway of adults does not similarly function in newborn infants due to diminished bacterial conversion of nitrate to nitrite in the mouth,15 making the diet a particularly important source of nitrite. Indeed, plasma nitrite levels are lower in newborn infants in the NICU than in adults,16 but the contribution of dietary nitrite and nitrate is not known. Concentrations of nitrate and nitrite in human breast milk have previously been reported in milk from mothers of healthy term infants.17,18 However, the effect of preterm birth and of common manipulations such as freeze-thaw cycles and storage on these concentrations have not been reported.

In this study we hypothesized that the freeze-thaw and storage of breast milk results in significant reductions in the dietary intake of nitrate and nitrite of newborns. We further hypothesized that nitrite and nitrate intake would be significantly reduced in infants receiving infant formula or intravenous parenteral nutrition (PN) compared to infants receiving fresh breast milk. We report that the levels of nitrate and nitrite change in the handling and storage of breast milk and describe potential mechanisms by which these levels change, including an examination of the roles of various key milk proteins that may contribute to nitrite metabolism.

Methods

The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Loma Linda University. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified.

Breast Milk and Formula Collection and Processing

Fresh breast milk was collected from 11 mothers of term infants and 13 mothers of preterm infants. The demographics of these mothers and their infants are provided in Table 1. Feeding, breast pumping, and milk collection routines were not changed by participation in the study. After milk had been expressed for the first 2 minutes of pumping, a 3-milliliter sample of newly expressed milk was collected in a polyurethane bottle, then divided into 500 μL aliquots and placed on ice. A portion of these aliquots was then immediately placed in a −20°C freezer, while the remainder was assayed for nitrite and nitrate concentrations within 30 minutes of collection. To measure the effect of freeze-thawing, frozen samples were thawed on ice ∼48 hours after collection and then assayed for nitrite and nitrate.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Term (>36 weeks) | Preterm (<35 weeks) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of women, n | 11 | 13 |

| Maternal age, years | 28.4 ± 2.4 | 28.9 ± 2.0 |

| Parity, n | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.7 |

| Times breast pumped before donation, n | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 0.4 |

| Number of infants, n | 11 | 13 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 39.4 ± 0.3 | 30.8 ± 0.7 |

| Birth weight, grams | 3158 ± 323 | 1390 ± 180 |

| Infant age at time of collection, days | 24.3 ± 8.7 | 18.9 ± 3.9 |

Nitrite concentrations of colostrum (milk expressed days 1-3), transition milk (expressed days 4-7), and mature milk (expressed days >7)18 were measured to follow changes during the first 3 weeks after giving birth. Samples were collected daily from 12 lactating women and immediately stored at −20°C until assay. Nitrite and nitrate concentrations were also analyzed in a number of infant formulas used in the NICU of the Loma Linda University Children's Hospital (LLUCH). These included: Enfamil Premature Lipil (Mead Johnson Nutritionals, Evansville, IN); Enfamil Lacto Free Lipil, Enfamil ProSobee Lipil, Enfamil EnfaCare 22, Enfamil Premium Infant, Similac Special Care (Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH); Similac NeoSure, Similac Advance EarlyShield, Pregestimil Lipil (Mead Johnson Nutritionals); and Nestlé Good Start (Nestlé Infant Nutrition, Florham Park, NJ). Assays were performed in 3 samples from 2 different lots of each formula. The nitrite concentrations were also measured in 5 samples of starter parental nutrition (sPN) and 14 samples of parenteral nutrition (PN) used for infants unable to receive milk or formula feeds.

Nitrite Metabolism in Breast Milk

The metabolism of nitrite in breast milk was assessed in a series of experiments in which nitrite was added to freezethawed samples of breast milk to initial concentrations of ∼12 μM. The milk was then incubated at 37°C (unless otherwise stated) and changes in nitrite concentrations were measured over a 5-hour time course.

To determine the effect of temperature on the metabolism of nitrite in breast milk, samples were incubated at 0°, 10°, 25°, and 37°C. In a separate study, aliquots of milk were boiled for 5 minutes to denature proteins prior to incubation at 37°C.

To test whether nitrite was being oxidized to nitrate, nitrite was added to 6 samples of milk and both nitrite and nitrate concentrations were measured over a 5-hour time course. In a separate experiment, additional nitrite was added to breast milk samples for final concentrations ranging from 10 μM to 160 μM and the increase in nitrate was measured after 5 hours. The increase in the nitrate concentration in a control sample of milk was subtracted from the rise in nitrate measured in the nitrite supplemented samples and plotted versus the initial nitrite concentration.

To assess the role of lipids in the stability of nitrite in breast milk, lipids were removed from 10 samples of milk by either chemical or centrifugation methods. The chemical method utilized an adaptation of a method for the delipidation of plasma,19 while the centrifugation method involved centrifuging the milk twice at 13,400 rpm for 90 seconds. The lipid content was measured before and after the delipification procedures using a Calais Human Milk Analyzer, a midrange infrared spectrophotometer (Metron Instruments, Inc, Solon, OH).

To measure whether nitrite is reduced to NO in breast milk, nitrite was added to breast milk and then 100 μl of sample was immediately injected into buffered saline solution (pH = 7.4) in a purge vessel being continuously sparged with argon in line with a chemiluminescence NO detector. The presence of NO formation was detected over a period of 20 minutes (model 280i NO analyzer, Sievers Instruments, Boulder, CO). The lower limit of NO detection by this method was 20 nM. The possibility of a flux of nitrite reduction to NO that could subsequently be oxidized back into nitrite was examined by incubating milk samples with the NO scavenger 2-4-carboxyphenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (cPTIO) (final concentration 200 μM). Additionally, to address the possibility that nitrite was being reduced to NO and then combining with thiols to produce s-nitrosothiols, nitrosothiol concentrations were measured in 6 samples of breast milk over a 3-hour period following the addition of nitrite using a method described previously.20 The possible role of thiols was also assessed by measuring the effect of addition of 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM)21 on the rate of nitrite metabolism. To assess whether nitrite metabolism was dependent on enzymes with oxidizable transition metals, experiments were performed after addition of 10 mM ferricyanide (FeCN).

To determine the role of dissolved oxygen in nitrite metabolism in breast milk, 6 samples of milk were equilibrated with gas phases of various mixtures of nitrogen and oxygen. The oxygen tension of the samples were adjusted to approximately <5, 7, 37, 73, or >600 mmHg by measuring the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) in the sample (Radiometer, model ABL5, Copenhagen, Denmark). The rate of nitrite metabolism was determined by measuring the magnitude of decrease in nitrite concentrations after incubation for 60 minutes at 37°C.

To test the possibility that xanthine oxidase was involved in the metabolism of nitrite, experiments were conducted following the addition of 100 μM of the selective antagonist allopurinol. A possible role for the enzyme lactoperoxidase (LPO) was studied by adding 1 of 3 selective inhibitors of LPO to samples of breast milk. First, to inactivate the heme center of LPO, 10 μM of 2-mercaptio-1-methylimidazole (2-MMI) was added to breast milk. As a second test, 4 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT), a compound that inhibits LPO by covalent binding to the polypeptide chain of LPO rather than the heme,22 was added to a separate set of samples. In a third set of samples, the LPO inhibitor dapsone was added to a concentration of 0.6 mmol/L. Optimal concentrations for each inhibitor were chosen in accordance with those used in the literature.22-25 To assess whether addition of exogenous LPO would accelerate the loss of nitrite, 10 μL of 1.33 mM LPO from bovine milk was added to 5 mL of breast milk for a final LPO concentration of 500 nM. Nitrite was added to the sample immediately before 1 mM hydrogen peroxide was added to initiate the reaction. Control samples lacked hydrogen peroxide. The samples were incubated at 37°C and the nitrite concentrations were measured after 10 seconds and 1, 2, 3, 30, and 60 minutes.

Nitrite and Nitrate Assays

Nitrite concentrations were measured by triiodide chemiluminescence as described by Pelletier et al,26 enabling quantification above 10 nM with a precision of ±5 nM. Nitrate concentrations were measured by triiodide chemiluminescence after reduction to nitrite with a nitrate reducing enzyme as previously described.15

Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error. Differences between study groups were detected using a t-test when the tested hypothesis involved only 2 sample groups and a 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis when 3 or more sample groups were involved. One-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used to detect significant changes from baseline measurements in time-course experiments. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis was used to detect significant differences between groups in time-course experiments. The overall rate of nitrite metabolism in breast milk was determined by fitting nitrite disappearance curves to a monoexponential equation. Where indicated, the initial rate of nitrite metabolism was determined as the amount of nitrite consumed during the first 60 minutes following addition of nitrite. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5 for Mac OS X (Graphpad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Nitrite and Nitrate Concentrations in Breast Milk and Formula

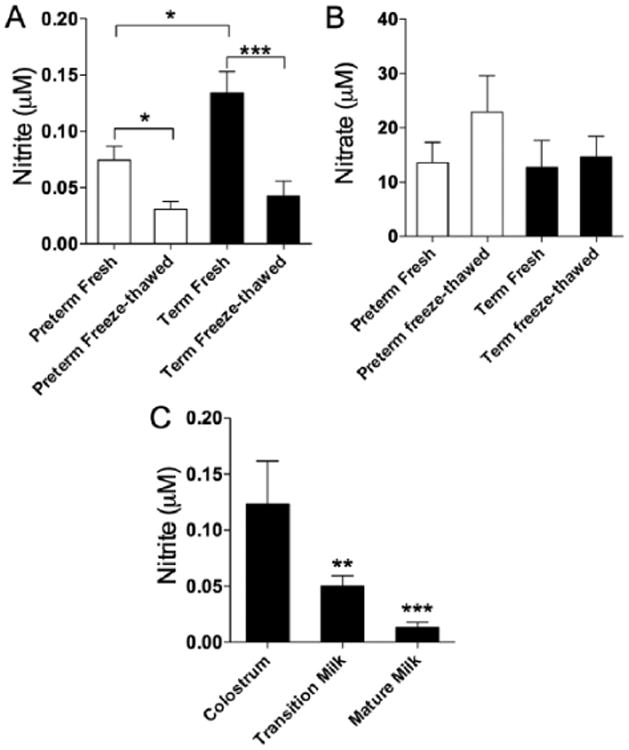

The nitrite concentrations of fresh and freeze-thawed breast milk from mothers of term and preterm infants are shown in Figure 1A. Nitrite concentrations in the milk of the mothers of preterm infants were significantly less than in milk from the mothers of term infants (0.07 ± 0.01 μM vs 0.13 ± 0.02 μM, respectively, P < .01). After freeze-thawing, nitrite concentrations were significantly decreased in the milk of mothers of both preterm and term infants (0.03 ± 0.01 μM and 0.04 ± 0.01 μM, respectively, P < .05 compared to fresh milk).

Figure 1.

Comparison of (A) nitrite and (B) nitrate concentrations in breast milk of mothers of term and preterm infants and after freeze-thawing. (C) Nitrite concentrations are higher in colostrum than transition (**P < .01) or mature milk (***P < .001).

Nitrate concentrations averaged about 100-fold higher than the nitrite levels in breast milk, as shown in Figure 1B. Nitrate in the milk of the mothers of preterm infants (13.6 ± 3.7 μM) did not differ significantly from nitrate concentrations in the milk from mothers of term infants (12.7 ± 4.9 μM). Nitrate concentrations tended to increase following freeze-thawing, but this change did not reach statistical significance.

To examine changes in nitrite concentrations in milk in the days following birth, samples were collected from 12 lactating mothers during the first 21 days postpartum (Figure 1C). In the first 3 days after birth, the nitrite concentration averaged 0.12 ± 0.03 μM. Nitrite concentrations decreased significantly over time following parturition, falling to 0.05 ± 0.01 μM in days 4 through 7 (1-way ANOVA, P < .01) and 0.01 ± 0.005 μM in days 8 through 21 (P < .001).

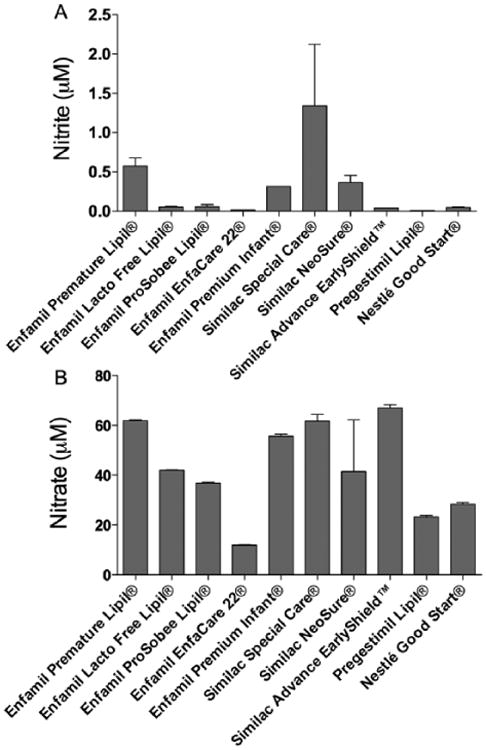

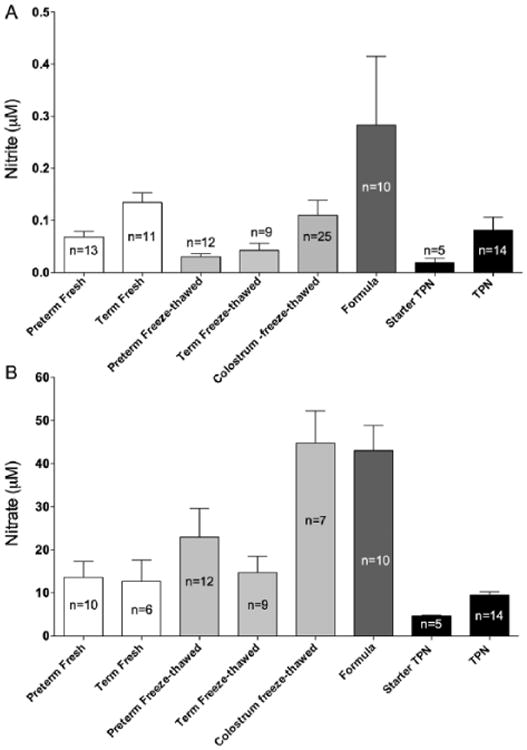

In a convenience sample of commercially available infant formulas used commonly in the LLUCH NICU, nitrite and nitrate concentrations averaged 0.28 ± 0.1 μM and 43 ± 5.8 μM, respectively (Figures 2A, 2B). The nitrite concentrations were also measured in sPN and PN. Nitrite concentrations averaged 0.02 ± 0.008 μM in sPN and 0.08 ± 0.03 μM in PN. Nitrate concentrations averaged 4.6 ± 0.2 μM in sPN and 9.5 ± 0.8 μM in PN. Figures 3A, 3B include the nitrite and nitrate concentrations of the PN samples alongside the mean concentrations in breast milk, colostrum, and formula.

Figure 2.

(A) Nitrite concentrations and (B) nitrate concentrations in a variety of formulas used in neonatal intensive care units. Nitrite levels vary widely, ranging from barely detectable to more than 13-fold higher than breast milk.

Figure 3.

Summary (A) nitrite and (B) nitrate concentrations in all forms of nutrition provided to newborns in an intensive care setting. The nitrite and nitrate concentrations in starter PN and PN samples are similar to those found in breast milk.

Nitrite Metabolism in Breast Milk

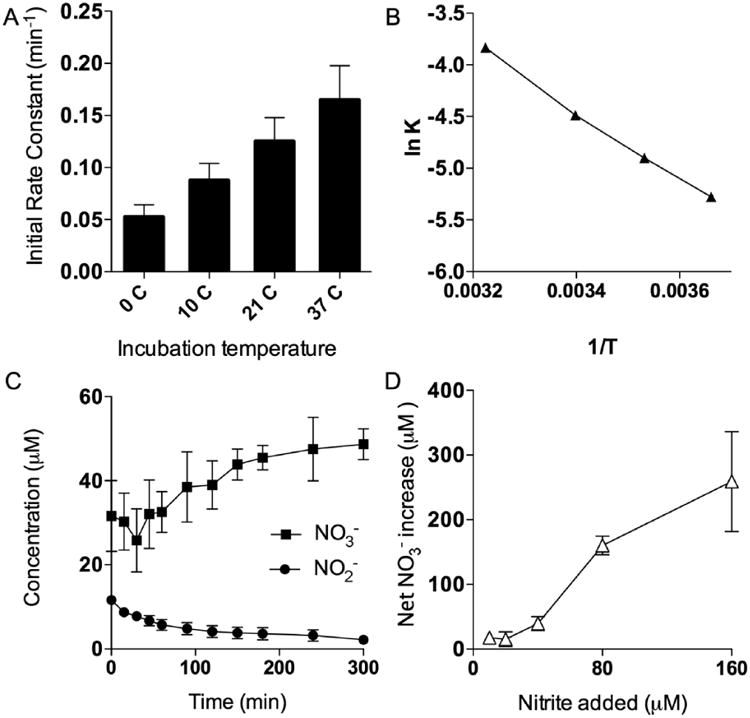

The lower concentrations in the freeze-thawed milk compared to fresh samples indicated a time-dependent metabolism of nitrite. This was confirmed by measuring the disappearance of 12 μM nitrite added to freeze-thawed milk and incubated at 37°C. Under these conditions, nitrite concentrations decreased in a manner approximating first-order kinetics, with a rate constant of 0.020 ± 0.003 min−1 and an effective half-life of 32 minutes. The initial rates of nitrite metabolism of breast milk incubated at the different temperatures are shown in Figure 4A. An Arrhenius plot of the nitrite concentrations and temperature, shown in Figure 4B, revealed an activation energy of 6551 cal mol−1 and a Q10 of 1.5. As shown in supplemental Figure S1, this rate of disappearance was temperature dependent, with rate constants of 0.010 ± 0.001 min−1, 0.007 ± 0.001 min−1, and 0.005 ± 0.002 min−1 at 21°, 10°, and 0°C. When the milk was boiled for 5 minutes to denature proteins, the nitrite concentrations remained stable when incubated at 37°C (data not shown).

Figure 4.

(A) Nitrite metabolism rates under various temperature conditions. (B) Arrhenius plot of nitrite metabolism and temperature. (C) Nitrate and nitrite concentrations in 6 samples of breast milk incubated over 5 hours. (D) Relationship between initial nitrite concentration and nitrate production.

To examine the possibility that nitrite was being oxidized to nitrate, we made measurements of nitrite and nitrate concentrations following addition of nitrite to an initial concentration of 12.5 μM in breast milk. We observed an increase in nitrate concentrations that was comparable in magnitude to the decrease in nitrite concentrations (Figure 4C), consistent with a pathway of oxidation of nitrite to nitrate. To confirm these results, additional nitrite was added to a second set of breast milk samples for final concentrations ranging from 10 to 160 μM. The increase in the nitrate concentration in a control sample of milk was subtracted from the rise in nitrate in the nitrite supplemented samples and plotted vs the initial nitrite concentration (Figure 4D).

We next examined a number of different possible mechanisms for the disappearance of nitrite including its reaction with lipids, oxidation/reduction, and enzymatic catalysis by key milk proteins.

The role of lipids was assessed by measuring nitrite metabolism before and after delipidation of breast milk samples from mothers of term infants. Fat content in these samples averaged 2.6 ± 0.1 g/dl and decreased to 1.1 ± 0.2 g/dl after delipification for samples that were delipified via the chemical process. The extent of delipification was similar for the centrifugation method, with the starting fat content averaging 3.2 ± 0.4 g/dl and the ending amount averaging 0.8 ± 0.1 g/dl after delipification (P = .31). However, lipid removal, by either a combination of chemical delipification and centrifugation or centrifugation only, had no effect on the rate of metabolism of nitrite, as shown in Figure 5A, and thus the role of lipids could be discounted.

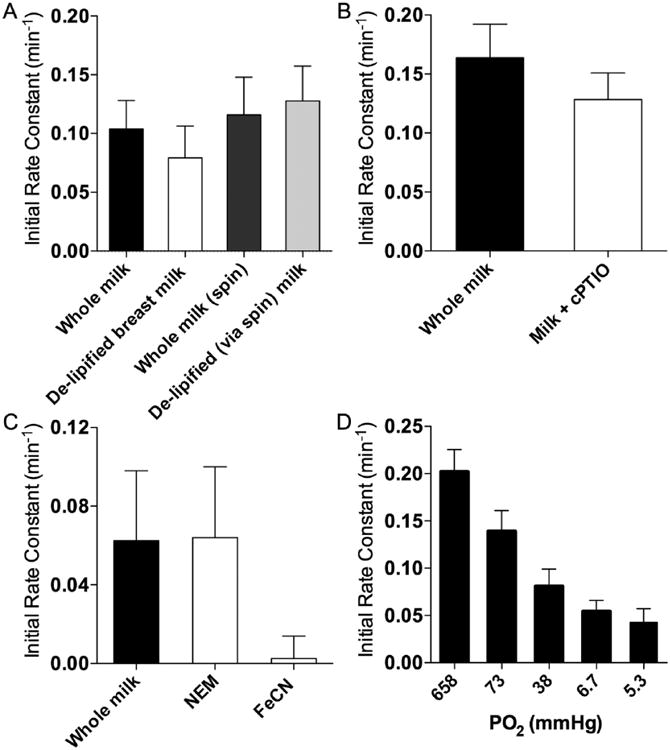

Figure 5.

(A) Initial rates of nitrite metabolism in breast milk after removal of lipids, (B) treatment with the NO scavenger, 2-4-carboxyphenyl-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide, (C) incubation with N-ethylmaleimide or ferricyanide, or (D) at different partial pressures of oxygen.

We were unable to detect any free NO in breast milk following addition of nitrite, indicating no reduction of nitrite to NO. We also considered the possibility of a rapid flux of nitrite reduction to NO with subsequent oxidation of the NO back into nitrite. If so, the removal of NO being produced would be anticipated to speed the metabolic loss of nitrite by mass action. However, addition of the NO scavenger, cPTIO, did not change the rate of nitrite metabolism (Figure 5B and supplemental Figure S2). Alternatively, any NO produced might have immediately reacted with cysteine residues to produce nitroso compounds, including s-nitrosothiols (SNO). However, we did not detect measurable amounts of SNO production in any of the milk samples. The combination of these results speaks against a reductive process that might have converted nitrite to NO.

We also investigated the potential roles of catalytic proteins in the metabolism of nitrite. The prevention of nitrite metabolism after boiling milk is consistent with an enzyme-mediated metabolism of nitrite. The metabolic loss of nitrite was halted by the addition of 10 mM ferricyanide, suggesting the involvement of a protein containing an oxidizable transition metal (Figure 5C and supplemental Figure S3). Other experiments tested the possible binding of nitrite or its metabolic byproducts to thiol groups. Again, the rate of nitrite disappearance was not affected by the presence of 2 mM NEM used to block available thiol groups (Figure 5C).

The role of oxygen in nitrite metabolism was tested by measuring rates of nitrite disappearance in breast milk samples after equilibration with various concentrations of oxygen. We found the initial rate of nitrite disappearance to be directly related to oxygen tensions (Figure 5D). These results are consistent with an oxygen-dependent oxidation of nitrite to nitrate. In further support of this mechanism, nitrate production was observed to increase in approximate proportion to the magnitude of nitrite disappearance, as shown in Figures 4C, 4D.

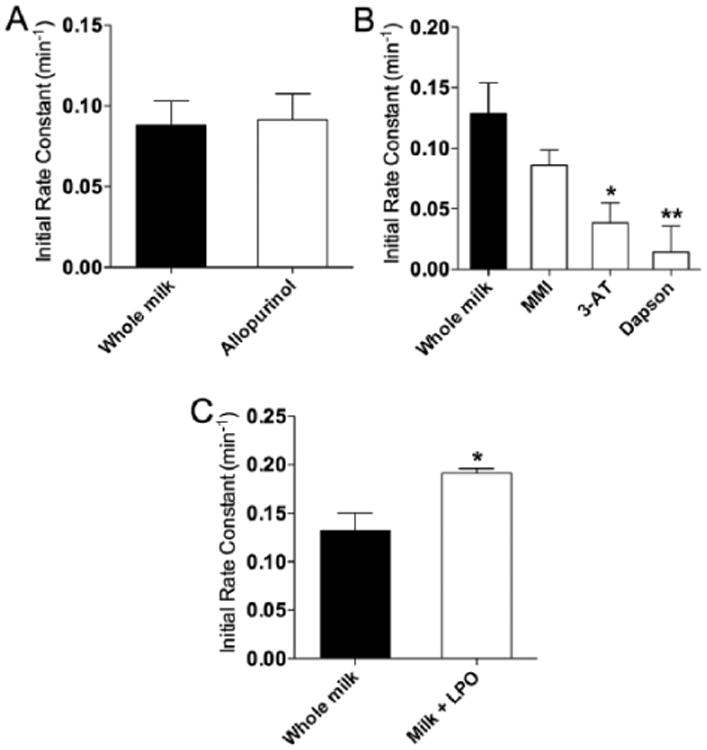

The blockade of xanthine oxidase, an enzyme previously reported to metabolize nitrite to NO in breast milk,27 by addition of allopurinol had no effect on the rate of nitrite disappearance (Figure 6A and supplemental Figure S4). Lactoperoxidase, an enzyme previously reported to be present in breast milk,28 has been shown to contribute to oxidative mechanisms in milk,29 in addition to catalyzing the oxidation of nitrite in vitro.30 Inhibition of LPO's iodide-binding site with 2-mercaptio-1-methylimidazole resulted in the blockade of nitrite metabolism. Similarly, inhibiting the polypeptide chain of LPO with 3-AT resulted in the complete inactivation of enzymatic activity, corresponding with a lack of nitrite metabolism (Figure 6B). Treating milk samples with excess dapsone, a potent inhibitor of LPO activity, also effectively prevented the loss of nitrite over time. The nitrite metabolism curves for milk treated with the LPO inhibitors are shown in supplemental Figure S5. The addition of exogenous LPO (final concentration, 500 nM) also accelerated the loss of nitrite, shortening the half-life from ∼30 to ∼16 min (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

(A) Initial rates of nitrite metabolism in breast milk after treatment with the xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol; (B) inhibition of lactoperoxidase by 2-mercaptio-1-methylimidazole, 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole, or Dapson; (C) or addition of purified lactoperoxidase enzyme.

Discussion

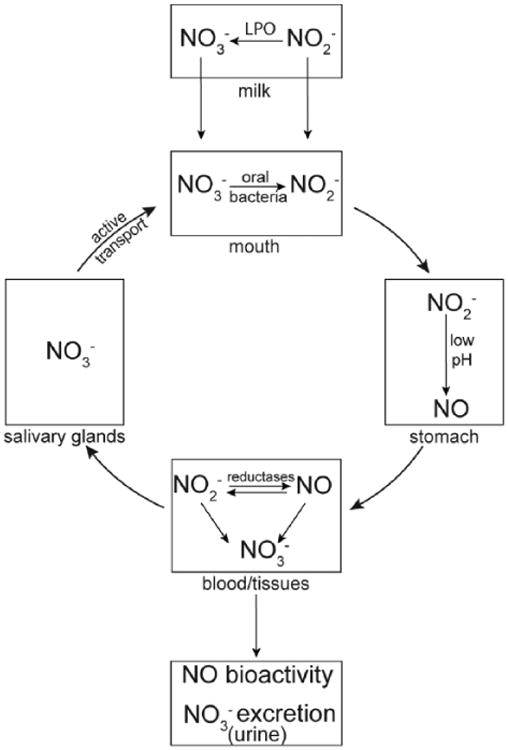

The current study sought to determine whether the dietary intake of nitrite and nitrate is limited for term and preterm infants in the NICU compared to normal infants. We find that the dietary intake of nitrate and nitrite is significantly lower in infants receiving freeze-thawed breast milk or breast milk from mothers of preterm infants or in infants receiving PN. In addition, the intake of nitrate and nitrite of infants receiving infant formulas range from less than to more than that of infants receiving fresh breast milk, depending on the brand of formula. Finally, the findings of the current experiments also add a novel breast milk component to the nitrate-nitrite-NO system, with nitrite being oxidized to nitrate by LPO, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schema showing the pathways and interconversions of nitrate, nitrite, and nitric oxide.

We find widely variant concentrations of nitrite and nitrate in the diets of newborn infants in the NICU. The lowest levels of nitrite and nitrate measured were those in sPN at nearly undetectable concentrations, whereas standard PN had concentrations comparable to those of breast milk. Infant formulas, however, were found to have levels ranging from undetectable to nearly 100 times those of breast milk. This suggests that the manufacturers of commonly used infant formulas do not tightly control for nitrite and nitrate concentrations, especially as levels were found to vary significantly across different lots of the same formula.

With regard to breast milk, our results show that nitrite intake is limited for preterm infants in the NICU compared to term infants. The milk of the mothers of preterm infants has significantly less nitrite than the milk of the mothers of term infants, a finding in line with studies that have shown that the breast milk of mothers of term and preterm infants differ with respect to a number of analytes.31-34 Consistent with reports that the composition of milk changes in the days postpartum,18,34 we find that nitrite concentrations decrease from relatively high levels in colostrum to lower levels in the days and weeks after birth. The physiological importance of this progression is not known, but it is worth noting that it is not matched in the care of newborns in the NICU where initial feeds may be delayed and concentrations in sPN are well below those of breast milk.

Nitrite Metabolism in Breast Milk

In all samples of breast milk analyzed, nitrite concentrations fell after freeze-thawing. Our experiments indicate that the mechanism for this fall involves the metabolism of nitrite by LPO. In support of this idea, we demonstrate that nitrite metabolism is oxygen-dependent, blocked by the presence of FeCN to oxidize the heme moiety of LPO, and is blocked by 3 different selective antagonists of LPO activity. We also demonstrate that the metabolism of nitrite in breast milk is accelerated by the addition of exogenous LPO. This idea is consistent with previous reports that LPO is known to contribute to oxidative mechanisms in milk29 and to metabolize nitrite in vitro.30

In contrast to previous reports that nitrite is reduced to NO by xanthine oxidase in breast milk,35 we observed no change in the rate of nitrite metabolism following addition of allopurinol to block xanthine oxidase activity. Likewise, addition of the NO scavenger cPTIO also had no effect. Finally, the rate of nitrite metabolism was observed to be directly proportional to oxygen concentrations, in contrast to the inverse relationship that would be expected from the reduction of nitrite by xanthine oxidase.36

The observation that FeCN prevented nitrite metabolism, together with evidence of the involvement of oxygen, suggested the involvement of an oxidative process involving a hemecontaining protein. Lactoperoxidase falls into this category and is known both to contribute to oxidative mechanisms in milk38 and to metabolize nitrite in vitro.30 Our finding that each of the 3 LPO antagonists studied abolished nitrite disappearance strongly indicates a role for LPO in the metabolism of nitrite in breast milk. Further supporting the role of LPO in the metabolism of nitrite, we found that adding purified LPO enhanced the conversion of nitrite to nitrate by approximately 2-fold.

Neonatal Nitrite and Nitrate Ingestion

Based on the values reported in this study, we have estimated the daily intake of nitrate in newborns in the NICU and compared this to adults. Assuming a representative milk intake of 150 ml•kg−1•day−1 and based on the nitrite and nitrate concentrations measured in our study, infants consuming fresh breast milk would ingest 0.0007 mg•kg−1•day−1 of nitrite and 0.12 mg•kg−1•day−1 of nitrate. This may be compared to adult ingestion of nitrite of ∼0.109 mg•kg−1•day−1 and ∼2.65 mg•kg−1•day−1 of nitrate, based on an average of 7 studies summarized by Pennington.39 Thus, on a per kg body weight basis, neonatal intake of nitrite and nitrate are only ∼0.6% and ∼5% of the adult, respectively. In addition, nitrite intake would decrease another 50%-75% if the milk is freeze-thawed prior to ingestion and by another 50% if the milk came from the mother of a preterm infant. For infants who are fed infant formula instead of breast milk, nitrite and nitrate intake may range from markedly lower to several-fold above that of breast milk–fed infants, and all formulas provide less nitrite and nitrate than the average adult diet. The amount of nitrite and nitrate being administered to infants receiving PN is 50%-80% less than that ingested by term infants receiving fresh breast milk. To date, we are unaware of any adult studies examining the effects of chronically low intake of nitrate and nitrite similar to that of infants. Consequently, the physiological effects of this deficiency in newborns cannot be compared to similar deficiencies in adults.

Relation to plasma nitrite levels

We have recently shown that plasma levels of nitrite in infants in the NICU average only 35%-55% of the levels of adults.16 One potential explanation is the current finding that infants ingest far lower amounts of nitrite and nitrate relative to adults. Demonstrating this effect, 2 recent studies showed a nearly 50% reduction in plasma nitrite and nitrate concentrations in rats given diets low in nitrite and nitrate.40,41 However, it remains to be determined whether reduced plasma nitrite levels in newborn infants is beneficial or detrimental and thus optimal levels of nitrate and nitrite in the diet of infants are as yet unknown.

It is important to consider that until recently, these anions were solely considered to be toxic by-products of NO metabolism because of their potential ability to form carcinogenic N-nitrosamines and methemoglobin (MetHb).42 Cases of methemoglobinemia have contributed to the idea that nitrate and nitrite ingestion must be carefully regulated for infants under 3 months of age. However, even the high nitrate and nitrite levels we measured in infant formulas are well below concentrations known to cause methemoglobinemia, so we can assume that there is a wide range of safe nitrite and nitrate concentrations in the nutrition sources of newborn infants used today. Moreover, infants exposed to nitrate intakes as high as 700 mg/day maintained nontoxic MetHb levels43 and even when MetHb levels are artificially inflated in newborn cord blood, there is sufficient MetHb reductase activity such that the halflife of MetHb is only ∼3.5 hours.44

Clinical Implications

The current findings inform speculation on the relationship between ingested nitrate and nitrite and the occurrence of newborn necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a disease that is characterized by a combination of decreased gastrointestinal blood flow, breakdown of the mucus barrier lining the lumen of the gut, and invasion by pathogenic bacteria.45 Nitric oxide, which can be derived from swallowed nitrite, has been shown to counteract all 3 of these factors in adult animal models.13,14,46,47 It is clear that the dietary intake of nitrite and nitrate is significantly lower in the infant compared to the adult, whether the infant is receiving fresh breast milk, freeze-thawed breast milk, infant formula, or PN. We have demonstrated previously that the endogenous reduction of nitrate to nitrite is markedly diminished in the newborn infant due to a lack of oral nitrate-reducing bacteria and significantly reduced saliva production.15 As a result, the impact of adding nitrate to the diet may be limited. Alternatively, addition of nitrite may provide an important source of NO to support the integrity of the gut lining by promoting enteric blood flow and mucus production. Notably however, our results do not support the recent postulate that formula-fed infants are predisposed to NEC because of deficient nitrate or nitrite intake,48 as we measure concentrations in most formulas for preterm infants to be well above those of breast milk.

Aside from NEC, premature infants are also at significant risk of suffering from hypoxic/ischemic injury due to dysregulation of cerebral blood flow (eg, intraventricular hemorrhage and periventricular leukomalacia) and episodes of inadequate systemic oxygenation. One possible consequence of low plasma nitrite concentrations would be a diminished capacity of this anion to function as a reservoir of NO bioactivity, a pathway thought to be important in protecting tissues against ischemic stress2-7 (also see recent review by Weitzberg and Lundberg50). Animal studies from multiple laboratories, species, and disease models now support the idea that increasing plasma nitrite levels, in some cases by as little as 2- to 3-fold, may protect against hypoxic/ischemic stress (see review by Dezfulian et al49). Interestingly, plasma nitrite concentrations of healthy term newborns are ∼30% lower than those of adults and increase by ∼2-fold with no known adverse effects during administration of inhaled NO (20 ppm) to infants with pulmonary hypertension.16 However, there are not yet any clinical reports on the therapeutic effects or safety of exogenous nitrite to treat ischemia/reperfusion injury, and although it may have therapeutic possibilities, there are also inherent risks to consider. For example, in adults, ingestion of nitrate results in a significant decrease in arterial blood pressure,10 which would be undesirable in the care of most premature infants. In addition, MetHb production is of particular concern in neonates as they possess low levels of MetHb reductase activity,44 and compared to adults, fetal hemoglobin is more rapidly oxidized to methemoglobin by reaction with nitrite.50 Thus, the possibility of methemoglobinemia cannot be ignored.

In summary, infants in neonatal intensive care units ingest markedly lower levels of nitrate and nitrite than adults on a per kg basis, possibly contributing to lower circulating concentrations in the plasma. The naturally occurring enzyme lactoperoxidase is likely a primary factor in the oxidation of nitrite to nitrate during the handling and storage of breast milk and is likely responsible for the ∼65% fall in nitrite concentrations that occurs through freeze-thawing, potentially exacerbating the effects of the little dietary nitrite made available to infants. Whether this limited ingestion puts the newborn infant population at risk for gastrointestinal and cardiovascular diseases or whether supplementation of these anions in the diet would be beneficial on one hand or safe on the other calls for future study.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Relevancy Statement.

The work in this manuscript extends the knowledge we currently have about the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in adults to the newborn infant population and takes a first step in exploring the dietary ingestion of nitrite and nitrate in infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) by measuring the levels found in the nutrition sources they receive. These studies indicate that infants in the NICU ingest significantly less nitrite and nitrate than adults due to the low concentrations measured in breast milk, infant formula, and parenteral nutrition. A deficiency of nitric oxide bioactivity may predispose infants to diseases of the GI tract and cardiovascular system.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the critical reading and helpful suggestions of Andre Dejam, MD, and Nathan Jones, BA; the expert technical assistance of Averil Austin; as well as the following Loma Linda University (LLU) lactation specialists for assistance with breast milk collection: Tonya Oswalt, RN; Dianne Wooldridge, RN; Pam Ruiz, RN; Jennifer Zirow, RN; and Mary Beth Maury-Holmes, RN.

Financial disclosure: This research paid for by intramural funding from the John Mace Pediatric Research Grant Fund of the Loma Linda University School of Medicine Department of Pediatrics and NIH HL095973 (ABB).

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article is available on the Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition website at http://jpen.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1.Tota B, Quintieri AM, Angelone T. The emerging role of nitrite as an endogenous modulator and therapeutic agent of cardiovascular function. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(18):1915–1925. doi: 10.2174/092986710791163948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung KH, Chu K, Ko SY, et al. Early intravenous infusion of sodium nitrite protects brain against in vivo ischemia-reperfusion injury. Stroke. 2006;37(11):2744–2750. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000245116.40163.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung KH, Chu K, Ko SY, et al. Effects of long term nitrite therapy on functional recovery in experimental ischemia model. Biochem and Biophys Res Comm. 2010;403:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duranski MR, Greer JJ, Dejam A, et al. Cytoprotective effects of nitrite during in vivo ischemia-reperfusion of the heart and liver. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1232–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb A, Bond R, McLean P, Uppal R, Benjamin N, Ahluwalia A. Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide during ischemia protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(37):13683–13688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402927101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickerodt PA, Emery MJ, Zarndt R, et al. Sodium nitrite mitigates ventilator-induced lung injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2012;117(3):592–601. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182655f80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tripatara P, Patel NS, Webb A, et al. Nitrite-derived nitric oxide protects the rat kidney against ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo: role for xanthine oxidoreductase. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(2):570–580. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Lauer T, et al. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35(7):790–796. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duncan C, Dougall H, Johnston P, et al. Chemical generation of nitric oxide in the mouth from the enterosalivary circulation of dietary nitrate. Nat Med. 1995;1(6):546–551. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webb AJ, Patel N, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Acute blood pressure lowering, vasoprotective, and antiplatelet properties of dietary nitrate via bioconversion to nitrite. Hypertension. 2008;51(3):784–790. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocha BS, Gago B, Barbosa RM, Lundberg JO, Radi R, Laranjinha J. Intragastric nitration by dietary nitrite: implications for modulation of protein and lipid signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(3):693–698. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin L, Qin L, Xia D, et al. Active secretion and protective effect of salivary nitrate against stress in human volunteers and rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;57:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersson J, Phillipson M, Jansson EA, Patzak A, Lundberg JO, Holm L. Dietary nitrate increases gastric mucosal blood flow and mucosal defense. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292(3):G718–724. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00435.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansson EA, Petersson J, Reinders C, et al. Protection from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced gastric ulcers by dietary nitrate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42(4):510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanady JA, Aruni AW, Ninnis JR, et al. Nitrate reductase activity of bacteria in saliva of term and preterm infants. Nitric Oxide. 2012;27(4):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim YI, Ninnis JR, Hopper AO, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide therapy increases blood nitrite, nitrate, and s-nitrosohemoglobin concentrations in infants with pulmonary hypertension. J Pediatr. 2012;160(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohta N, Tsukahara H, Ohshima Y, et al. Nitric oxide metabolites and adrenomedullin in human breast milk. Early Hum Dev. 2004;78(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hord NG, Ghannam JS, Garg HK, Berens PD, Bryan NS. Nitrate and nitrite content of human, formula, bovine, and soy milks: implications for dietary nitrite and nitrate recommendations. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(6):393–399. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cham BE, Knowles BR. A solvent system for delipidation of plasma or serum without protein precipitation. J Lipid Res. 1976;17(2):176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conahey GR, Power GG, Hopper AO, Terry MH, Kirby LS, Blood AB. Effect of inhaled nitric oxide on cerebrospinal fluid and blood nitrite concentrations in newborn lambs. Pediatr Res. 2008;64(4):375–380. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318180f08b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadowitz PD, Hubbard BA, Dabrowiak JC, et al. Kinetics of cisplatin binding to cellular DNA and modulations by thiol-blocking agents and thiol drugs. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(2):183–190. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doerge DR, Niemczura WP. Suicide inactivation of lactoperoxidase by 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole. Chem Res Toxicol. 1989;2(2):100–103. doi: 10.1021/tx00008a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandyopadhyay U, Bhattacharyya DK, Chatterjee R, Banerjee RK. Irreversible inactivation of lactoperoxidase by mercaptomethylimidazole through generation of a thiyl radical: its use as a probe to study the active site. Biochem J. 1995;306(Pt 3):751–757. doi: 10.1042/bj3060751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michot JL, Nunez J, Johnson ML, Irace G, Edelhoch H. Iodide binding and regulation of lactoperoxidase activity toward thyroid goitrogens. J Biol Chem. 1979;254(7):2205–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin K, Tomita M, Lonnerdal B. Identification of lactoperoxidase in mature human milk. J Nutr Biochem. 2000;11(2):94–102. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(99)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelletier MM, Kleinbongard P, Ringwood L, et al. The measurement of blood and plasma nitrite by chemiluminescence: pitfalls and solutions. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41(4):541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens CR, Millar TM, Clinch JG, Kanczler JM, Bodamyali T, Blake DR. Antibacterial properties of xanthine oxidase in human milk. Lancet. 2000;356(9232):829–830. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02660-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gothefors L, Marklund S. Lactoperoxidase activity in human milk and in saliva of newborn infants. Infect Immun. 1975;11(6):1210–1215. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.6.1210-1215.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostdal H, Bjerrum MJ, Pedersen JA, Andersen HJ. Lactoperoxidaseinduced protein oxidation in milk. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48(9):3939–3944. doi: 10.1021/jf991378n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Vliet A, Eiserich JP, Halliwell B, Cross CE. Formation of reactive nitrogen species during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of nitrite. A potential additional mechanism of nitric oxide-dependent toxicity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(12):7617–7625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ustundag B, Yilmaz E, Dogan Y, et al. Levels of cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-alpha) and trace elements (Zn, Cu) in breast milk from mothers of preterm and term infants. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005(6):331–336. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molinari CE, Casadio YS, Hartmann BT, Arthur PG, Hartmann PE. Longitudinal analysis of protein glycosylation and beta-casein phosphorylation in term and preterm human milk during the first 2 months of lactation. Br J Nutr. 2012:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512004588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wight NE. Donor human milk for preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2001;21(4):249–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulski JK, Hartmann PE. Changes in human milk composition during the initiation of lactation. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1981;59(1):101–114. doi: 10.1038/icb.1981.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hancock JT, Salisbury V, Ovejero-Boglione MC, et al. Antimicrobial properties of milk: dependence on presence of xanthine oxidase and nitrite. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(10):3308–3310. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.10.3308-3310.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Cui H, Kundu TK, Alzawahra W, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide production from nitrite occurs primarily in tissues not in the blood: critical role of xanthine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):17855–17863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801785200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silanikove N, Shapiro F, Shamay A, Leitner G. Role of xanthine oxidase, lactoperoxidase, and NO in the innate immune system of mammary secretion during active involution in dairy cows: Manipulation with casein hydrolyzates. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pennington JAT. Dietary exposure models for nitrates and nitrites. Food Control. 1998;9(6):385–395. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryan NS, Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Lefer DJ. Dietary nitrite restores NO homeostasis and is cardioprotective in endothelial nitric oxide synthasedeficient mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(4):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raat NJ, Noguchi AC, Liu VB, et al. Dietary nitrate and nitrite modulate blood and organ nitrite and the cellular ischemic stress response. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(5):510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milkowski A, Garg HK, Coughlin JR, Bryan NS. Nutritional epidemiology in the context of nitric oxide biology: a risk-benefit evaluation for dietary nitrite and nitrate. Nitric Oxide. 2010;22(2):110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hord NG, Tang Y, Bryan NS. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):1–10. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Power GG, Bragg SL, Oshiro BT, Dejam A, Hunter CJ, Blood AB. A novel method of measuring reduction of nitrite-induced methemoglobin applied to fetal and adult blood of humans and sheep. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103(4):1359–1365. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00443.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(3):255–264. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bjorne HH, Petersson J, Phillipson M, Weitzberg E, Holm L, Lundberg JO. Nitrite in saliva increases gastric mucosal blood flow and mucus thickness. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(1):106–114. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dykhuizen RS, Frazer R, Duncan C, et al. Antimicrobial effect of acidified nitrite on gut pathogens: importance of dietary nitrate in host defense. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40(6):1422–1425. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yazji I, Sodhi CP, Lee EK, et al. Endothelial TLR4 activation impairs intestinal microcirculatory perfusion in necrotizing enterocolitis via eNOS-NO-nitrite signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9451–9456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219997110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO. Novel aspects of dietary nitrate and human health. Annu Rev Nutr. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161159. published online April 29, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dezfulian C, Raat N, Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Role of the anion nitrite in ischemia-reperfusion cytoprotection and therapeutics. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(2):327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blood AB, Tiso M, Verma ST, et al. Increased nitrite reductase activity of fetal versus adult ovine hemoglobin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296(2):H237–246. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00601.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.