Abstract

Background

Lung cancer screening with annual chest CT is recommended for current and former smokers with ≥30+ pack-year smoking history. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are at increased risk of developing lung cancer and may benefit from screening at lower pack-year thresholds.

Methods

We used a previously validated simulation model to compare the health benefits of lung cancer screening in current and former smokers ages 55-80 with ≥30 pack-years to hypothetical programs using lower pack-year thresholds for individuals with COPD (≥20, ≥10, and ≥1 pack-years). Calibration targets for COPD prevalence and associated lung cancer risk were derived using the Framingham Offspring Study Limited Dataset. We performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate the stability of results across different rates of adherence to screening, increased competing mortality risk due to COPD, and increased surgical ineligibility in individuals with COPD. The primary outcome was projected life expectancy.

Results

Programs using lower pack-year thresholds for individuals with COPD yielded the highest life expectancy gains for a given number of screens. Highest life expectancy was achieved when lowering the pack-year threshold to ≥1 pack-year for individuals with COPD, which dominated all other screening strategies. These results were stable across different adherence rates to screening and increases in competing mortality risk for COPD and surgical ineligibility.

Conclusion

Current and former smokers with COPD may disproportionately benefit from lung cancer screening. A lower pack-year threshold for screening eligibility may benefit this high-risk patient population.

Keywords: lung neoplasms, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer screening, decision analysis

Introduction

In 2011, the National Cancer Institute published the results of the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), which demonstrated a 20% reduction in lung cancer (LC) mortality in current and former heavy smokers (≥30 pack-years) screened with annual low dose computed tomography (CT) versus standard chest X-ray.1 As a result, the United States Preventive Services Task Force issued recommendations for LC screening in current and former smokers ages 55-80 years with at least a 30 pack-year smoking history.2 However, there are risk factors other than smoking history which may help identify individuals who may benefit from LC screening.3-4 One important risk factor is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cohort studies have indicated that patients with COPD are 2-6 times more likely to develop LC than those without COPD.5-10 This elevation in risk persists after controlling for smoking exposure, which concurs with recent studies identifying factors that may predispose individuals for the development of both COPD and LC.11-13 Patients with COPD, however, experience higher competing mortality risks. In addition, some may not be eligible for surgical resection, the standard treatment for early-stage disease.

Simulation modeling can be used to project the long-term effects of cancer screening and treatment. The Lung Cancer Policy Model (LCPM) is a microsimulation model of LC development created to estimate the effectiveness of LC screening in populations at elevated risk.14-16 The purpose of this project was to use the LCPM to compare the health benefits of LC screening with chest CT using eligibility criteria that target individuals with COPD, compared with programs targeting individuals based on smoking history alone.

Methods

Model overview

The LCPM is an individual-level microsimulation model of LC development, diagnosis, and treatment that was developed to estimate the health benefits and cost-effectiveness of LC screening.15-17 The LCPM simulates the unobservable disease process as well as clinical events such as diagnostic tests, symptomatic presentation, and screening tests. Estimation of model parameters was accomplished via a combination of using published data and calibration, which involves populating the model with individuals with detailed smoking histories and simulating detailed clinical scenarios. Model outputs are calibrated to observed outcomes and tumor registry data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute.18 Additional details of the LCPM and model inputs have been previously described19-20 and are available online14 and summarized in the Appendix (see eAppendix, eTable 1, eFigure 1). In the sections below, we describe the approach used to incorporate spirometry-defined COPD as a risk factor for LC.

Data Source

Input parameters for COPD prevalence and elevated LC risk were calculated using longitudinal, de-identified data from the Framingham Offspring Study Limited Dataset (FOS-LDS) obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The study was reviewed and approved by our Institutional Review Board. Details of the FOS study design, inclusion criteria, and examination procedures have been previously published.21 The FOS study began in 1971 and includes 4,989 men and women ranging in age from 13-62 years at baseline. Of the 4,989 participants, 4,832 had both spirometric and smoking-related data for at least one exam. To prevent confounding of spirometry data due to asthma, we excluded 514 participants with a reported history of asthma, leaving 4,318 participants for analysis. LC data in the FOS were obtained through self-report, hospital records, and data from the National Death Index. LC diagnosis was confirmed based on pathology reports.

Lung Function Data

Spirometric methods in the FOS have been previously described.22 Lung volumes were obtained from spirometry testing of participants at exams 1 (1971-75), 2 (1984-87), 5 (1991-95), and 6 (1996-97). Participants performed all maneuvers until three satisfactory measurements were obtained. The largest values for forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were recorded. No bronchodilators were used.

We defined COPD using the lower limit of normal (LLN) criteria recommended by both the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society Task Force.23 By these criteria, an FEV1/FVC ratio below the 5th percentile of a healthy age- and sex-matched reference population is considered indicative of airway obstruction. Because COPD is defined as irreversible airway obstruction, participants who met criteria for COPD on one examination and had normal pulmonary function (FEV1/FVC > LLN) on any subsequent examination were considered not to have COPD.

We fit a generalized linear model (GLM)24 to repeated measures in the FOS-LDS data to calculate the probability of developing COPD in men and (separately) women as a function of age and pack-years using a log-link function and binominal error distribution. Age was categorized in five year intervals and smoking was categorized by pack-years (nonsmoking, <10 pack-years, 11-20 pack-years, 21-30 pack-years, 31-40 pack-years, and >40 pack-years). From these calibration targets, we derived annual incidence rates for COPD for male and female nonsmokers and relative risks (RR) of COPD by pack-year category (eTable 2). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

LC Risk

To calculate the adjusted risk of LC in participants with COPD in the FOS, we fitted a logistic regression model to predict LC diagnosis using forward selection of the following predictors: age at study entry, gender, average cigarettes per day, years smoked, years since quitting (in former smokers), and COPD status. Data from the last recorded exam were used. All variables were treated as continuous variables except for gender and COPD (binary variables). Gender and years of smoking did not meet a significance level of p<0.05 and were excluded from the regression model.

LCPM Extensions

The 95% confidence intervals for COPD prevalence in the FOS-LDS predicted by the GLM were used as calibration targets for COPD prevalence in the simulation model. The probability of developing LC in the LCPM is a set of five logistic functions (one for adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and other) dependent on age, age2, years of cigarette exposure, an interaction between age2 and cigarette exposure, number of cigarettes per day, a proxy for inherited risk in 4.7% of individuals, and years since quitting smoking (in former smokers).14 We added a coefficient to these functions to increase the risk of LC in individuals with versus without COPD, based on the odds ratio (OR) for LC diagnosis in individuals with COPD in the FOS-LDS. After adjustment of LC, we populated the model with 50-year-old male and female U.S. birth cohorts born in 1950 and re-calibrated the model to total LC observed in the SEER registry for the corresponding birth cohorts (eFigure 2).

Screening Strategies

We evaluated the health benefits of LC screening with annual low dose chest CT in 55-80 year old men and women compared with no screening using four different eligibility criteria: 1) ≥30 pack-years (30PY); 2) ≥30 pack-years or COPD and ≥20+ pack-years (30PY/20PY+COPD); 3) ≥30 pack-years or COPD and ≥10 pack-years (30PY/10PY+COPD); 4) ≥30 pack-years or COPD and ≥1 pack-year (30PY/1PY+COPD). Former smokers were eligible for screening if they had quit within the past 15 years. For the base case, we assumed 100% adherence. Only nodules >4mm in diameter at detection were further evaluated.25 We simulated 5 million men and (separately) women born in 1950 until death for each program.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was projected life expectancy (LE) across all individuals in the cohort, defined as time from birth until simulated death. Additional outcomes included the number of screening CTs performed, number of invasive procedures performed for benign nodules (including percutaneous biopsies and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery), and LC mortality reduction attributable to screening, expressed as the cumulative percentage decrease in the total number of LC deaths in the population (including individuals not screened) compared to no screening.

Efficiency of Strategies

We identified “efficient” strategies as those that produced the greatest gain in LE per incremental increase in number of CT screens performed. Strategies were ranked in order of increasing number of screens, and strategies that offered fewer benefits as another strategy yet required the same number of screens (i.e., dominated strategies) were eliminated per standard principles.26 Strategies that resulted in a higher incremental increase in screens per gain in LE compared with another strategy with a higher LE were considered eliminated by extended dominance. After elimination of dominated strategies, the remaining strategies were connected on an efficiency frontier. We similarly evaluated the efficiency of strategies by comparing the reduction in LC mortality relative to the number of invasive procedures performed for benign nodules.

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed one-way sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of the results when varying parameter values. Screening adherence was varied to simulate adherence rates of 80%, 60%, 40%, and 20%. We varied the adjusted OR of developing LC in individuals with COPD across the 95% confidence interval observed in the logistic regression analysis (from 1.35-4.03). Because patients with COPD have decreased LE relative to individuals without COPD,27 we performed a sensitivity analysis with adjusted competing mortality risks for individuals with COPD (see eAppendix and eTable3). We also increased the proportion of individuals with COPD who would be ineligible for surgical tumor resection from 7.7% (base case) to 13.3% to account for the approximately 5% of men and women with COPD in the FOS-LDS who would likely not be operative candidates due to severely reduced lung function (<0.45% predicted FEV1).

Results

COPD and LC Risk in the FOS-LDS

Baseline characteristics of FOS participants included in this analysis are described in Table 1. A total of 476 (11.0%) participants demonstrated evidence of COPD on spirometry. Age group and pack-year group were significant predictors of developing COPD in GLMs for both men and women (p<0.0001). COPD prevalence predicted by the LCPM agreed with that observed in the FOS-LDS in men and women (eFigure 3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in Framingham Offspring Study Limited Dataset included in analysis (n=4318).

| Characteristics | No. of Participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at Entry, mean (SD) | 54.2 years (12.7) |

| Male | 2,022 (46.8%) |

| Last Recorded Exama | |

| Exam 1 | 636 (14.7%) |

| Exam 2 | 408 (9.5%) |

| Exam 5 | 353 (8.2%) |

| Exam 6 | 2921 (67.7%) |

| Number of Exams, mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.1) |

| Smoking Statusb,c | |

| Current | 1124 (29.1%) |

| Former | 1555 (40.2%) |

| Never | 1188 (30.7%) |

| Cigarettes per Day, mean (SD) | 12.2 (14.3) |

| Years Smoked, mean (SD) | 17.0 (16.1) |

| Pack-Years, mean (SD) | 17.3 (22.0) |

| COPDd | 476 (11.0%) |

| FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted | 194 (40.8%) |

| FEV1 50-79% predicted | 245 (52%) |

| FEV1 < 50% predicted | 36 (7.6%) |

| Diagnosed with Lung Cancer | 78 (1.81%) |

Exams 3 and 4 did not include spirometry and therefore are not included.

Current and former smokers included smokers who had smoked at least one year; Former smokers were defined as smokers who had quit for at least one year.

Total is less than 4,318 due to missing data (n=451).

COPD was defined as FEV1/FVC below the lower limit of normal (LLN) for age- and sex-matched healthy reference populations

Parameter estimates from the logistic regression analysis of LC risk in the FOS-LDS are summarized in Table 2. LC was significantly associated with COPD (adjusted OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.35-4.03), age at study entry (adjusted OR 1.09, 95%CI 1.06-1.12), and average cigarettes smoked per day (adjusted OR 1.04, 95%CI 1.02-1.06), and inversely associated with years since quitting smoking (adjusted OR 0.90, 95%CI 0.86-0.94).

Table 2.

Results from logistic regression analysis predicting development of lung cancer in Framingham Offspring Study participants.

| Effect | Estimate | Wald 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age at Study Entry | 1.09 | 1.06-1.12 |

| Cigarettes per Day (CS, FS) | 1.04 | 1.02-1.06 |

| Years since quit (FS) | 0.90 | 0.86-0.94 |

| COPD | 2.33 | 1.35-4.03 |

Variables were treated as continuous variables, except for sex and COPD which were binary. Gender and years smoked did not meet criteria for statistical significance (p<0.05) and therefore were not included in the final regression model. CS = Current smokers, FS = Former smokers.

Effects of Screening

Outcomes for men and women for each screening strategy in the base case are presented in Table 3. In the absence of screening, average LE was 78.582 years in men and 81.784 years in women.

Table 3.

Comparative effectiveness of lung cancer (LC) screening using various eligibility criteria. Screening strategies included annual screening with low-dose chest computed tomography (CT) from ages 55-80. Values for life expectancy (LE) gain and LC mortality reduction are relative to no screening. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PY=pack-years.

|

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Strategy | Number of Screens (per 1,000 people) | LE Gain (days) | LC Mortality Reduction | Number of Screens (per 1,000 people) | LE Gain (days) | LC Mortality Reduction |

|

|

|

|

||||

| 30PY | 3,628 | 11.17 | 10.6% | 2,549 | 8.45 | 8.6% |

| 30PY/20PY+COPD | 3,723 | 11.57 | 11.0% | 2,754 | 9.34 | 9.5% |

| 30PY/10PY+COPD | 3,787 | 11.81 | 11.2% | 2,906 | 9.90 | 10.0% |

| 30PY/1PY+COPD | 3,846 | 12.05 | 11.4% | 2,986 | 10.21 | 10.3% |

|

|

|

|

||||

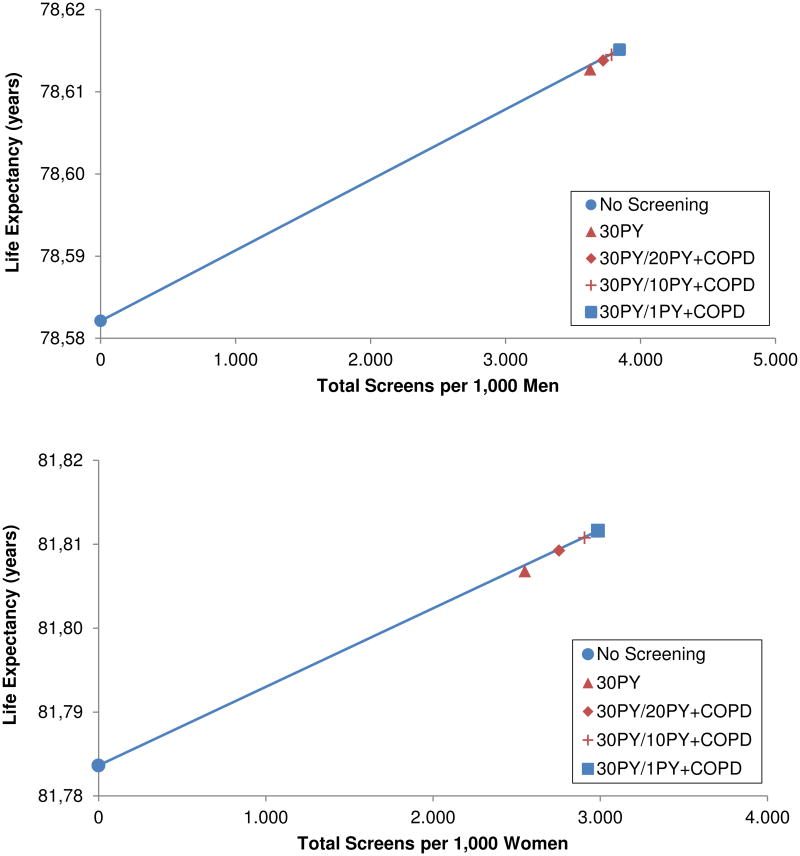

When comparing LE gains relative to the number of CT screens performed in both men and women, 30PY, 30PY/20PY+COPD, and 30PY/10PY+COPD were dominated by 30PY/1PY+COPD (Figure 1). Relative to no screening, 30PY/1PY+COPD increased LE by 0.033 years (12.05 days) in men and 0.028 years (10.21 days) in women.

Figures 1.

A-B. Efficiency frontiers of lung cancer screening strategies in men (top) and women (bottom) targeting patients based on evidence of COPD and smoking history or based on smoking history alone. Strategies with the highest incremental gain in life expectancy per increase in total number of screens are considered efficient and represented by blue symbols connected by the solid line. Dominated strategies are represented by red symbols.

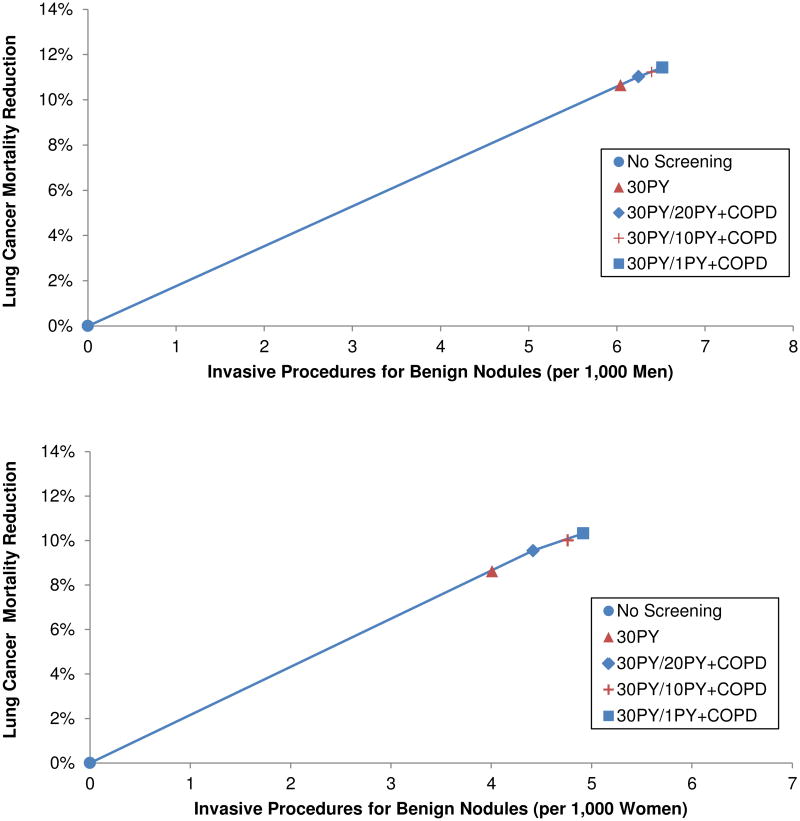

When the reduction in LC mortality was weighed against the number of invasive procedures performed for benign nodules, the efficiency frontiers included 30PY/20PY+COPD and 30PY/1PY+COPD (Figure 2). The 30PY and 30PY/10PY+COPD strategies were again eliminated by extended dominance. Compared with no screening, annual screening with 30PY/20PY+COPD reduced LC mortality in the population by 11.0% in men and 9.5% in women. Maximum mortality reduction was achieved with 30PY/1PY+COPD, which reduced mortality by 11.4% in men and 10.3% in women.

Figures 2.

A-B. Efficiency of screening strategies expressed as the number of invasive procedures performed for benign nodules relative to lung cancer (LC) mortality reduction in men (top) and women (bottom). Strategies with the highest incremental gain in LC mortality reduction relative to the increase in the number of invasive procedures performed for benign nodules are considered efficient and represented by blue symbols connected by the solid line. Dominated strategies are represented by red symbols. PY=Minimum pack-years of smoking.

Sensitivity Analyses

The efficiency of strategies remained stable for both men and women in most sensitivity analyses. The 30PY, 30PY/20PY+COPD, and 30PY/10PY+COPD strategies were dominated by 30PY/1PY+COPD in both men and women when varying screening adherence from 20-80%, increasing the probability of ineligibility for surgery in individuals with COPD, and increasing non-LC competing mortality risks for individuals with COPD. In both men and women, 30PY and 30PY/20PY+COPD appeared on the efficiency frontier when using the lower limit of the 95% CI for the OR of development of LC in individuals with COPD derived from the FOS-LDS (1.35); however, expanding criteria to 30PY/1PY+COPD remained on the efficiency frontier and resulted in an incremental gain of 0.001 LY (0.4 days) in men and 0.002 LY (0.7 days) in women relative to the 30PY/20PY+COPD strategy.

Discussion

The NLST demonstrated that annual screening with chest CT significantly decreased LC mortality in current and former smokers between the ages of 55-74 with at least 30 pack-years.1 We used a disease simulation model to show that expanding LC screening eligibility criteria to include current and former smokers with COPD and ≥1 pack-year yields higher LE gains relative to the number of screens required and is more efficient than screening current and former smokers based only on smoking history. Our results suggest that in future guidelines, lower pack-year thresholds should be considered for individuals with COPD who may not qualify for screening based on a 30 pack-year smoking history alone.

It is important to note that we simulated screening eligibility for individuals with evidence of COPD on pulmonary function testing and not the (likely fewer) individuals with a reported history of diagnosed COPD. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) have shown that almost two-thirds of people with evidence of airway obstruction on spirometry have not been clinically diagnosed with COPD.28 Screening current and former smokers for COPD is not currently advocated as there has been no perceived benefit of early detection of COPD to date, particularly in asymptomatic patients.29 Our results support the notion that early detection of COPD could be valuable for targeting LC screening.30 Individuals with COPD but no or mild symptoms would be a particularly important group to target, since they are likely to benefit most from screening given their better health status.

We are not aware of prior decision analyses of LC screening programs in patients with COPD, although COPD has been established as a risk factor that can identify individuals who may benefit from LC screening.31-32 An analysis of data from the Pittsburg Lung Screening Study demonstrated a 4-5 times higher rate of LC detection in individuals with spirometry-proven COPD screened for LC compared with those with normal lung function.33-34 A recent pilot study by de Torres and colleagues35 of LC screening in patients with mild to moderate COPD [Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 1 or stage 2)] demonstrated a 3.8-fold higher annual LC detection rate compared with that observed in the NLST,35-37 and demonstrated a significant survival benefit in individuals with COPD being screened for LC compared with those not being screened. Of note, both the Pittsburg Lung Screening Study and de Torres and colleagues defined COPD using the GOLD definition, which uses an absolute cutoff ratio of FEV1/FVC < 0.7,38 while we applied the LLN definition to the FOS-LDS cohort. The LLN has been advocated as a more conservative definition of COPD than an absolute cutoff, particularly in older adults since FEV1/FVC typically decreases with age.23, 39 One study suggests that decreased FEV1 is a better predictor of LC than the FEV1/FVC ratio, and that even patients with <90% predicted FEV1 have an increased risk of cancer.10 More longitudinal data are needed to identify pulmonary function characteristics that may be used to identify patients with elevated LC risk who may benefit from screening.

Our estimated LC mortality reduction (8.6% in women and 10.6% in men) from annual screening in current and former smokers with ≥30 pack-years is based on the reduction in LC deaths for the entire population (including individuals who were not screened) rather than the reduction in mortality for only individuals receiving screening. Thus, our projections are more generalizable to population-level metrics than to endpoints from clinical trials and therefore not directly comparable to the observed reduction in the NLST. When we limit the calculation to the subset of individuals who would be eligible for screening in the 30PY strategy, we calculate a mortality reduction (19%) similar to the NLST (20%). Additional information from modeling studies may provide insight into how the NLST results may translate to the general population.40-41

As with all modeling studies, ours has limitations. We made the simplifying assumption that COPD increases the risk of all LC histologies proportionately. However, there is some evidence to suggest that COPD may specifically increase the risk of squamous cell cancer.42-43 In addition, we assumed equal test performance of CT for detection of pulmonary nodules in patients with and without underlying COPD. Our estimate for relative risk of non-LC related death for patients with COPD is lower than has been reported in other observational studies.27 This may be due to milder disease severity in the FOS cohort, as many individuals who demonstrated evidence of COPD on spirometry did not report a diagnosis of COPD or symptoms. The LE benefits of screening may be less for individuals with severe COPD, although our efficiency frontier remained stable even when increasing the competing mortality risks from COPD and the proportion of patients with COPD who are ineligible for surgery. With respect to this limitation, we recognize the importance of considering an individual patient's functional status and their ability to tolerate treatment before recommending screening.

In conclusion, identifying current and former smokers with COPD could be an important tool for tailoring LC screening to patients who are most likely to benefit. Lower pack-year thresholds for LC screening than were used in clinical trials of LC screening may be beneficial for patients with COPD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GSG became a consultant to GE Healthcare in 2010. As of February, 2014, PMM is employed at Exponent, Inc. None of the other authors has any potential conflicts of interest. This research was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society (RSG 2008A060554, to GSG), the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA97337, to GSG and R00 CA126147 and U01CA152956, to PMM), Radiological Society of North America (Medical Student Grant, to KPL) and the Harvard Medical School Scholars in Medicine Office (KPL). There was partial support from NIH grant R01DA036497 for Dr. Kong and Mr. Johanson. The MGH Lung Cancer Policy Model is one of the National Cancer Institute Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) lung group models. This Manuscript was prepared using Framingham Offspring – Limited Data Set obtained from the NHLBI and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Framingham Heart Study or the NHLBI.

References

- 1.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer VA. Screening for Lung Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013 doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tammemagi MC, Katki HA, Hocking WG, et al. Selection criteria for lung-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:728–736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raji OY, Duffy SW, Agbaje OF, et al. Predictive accuracy of the Liverpool Lung Project risk model for stratifying patients for computed tomography screening for lung cancer: a case-control and cohort validation study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:242–250. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skillrud DM, Offord KP, Miller RD. Higher risk of lung cancer in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A prospective, matched, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:503–507. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-4-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasswa-Kintu S, Gan WQ, Man SF, Pare PD, Sin DD. Relationship between reduced forced expiratory volume in one second and the risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2005;60:570–575. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.037135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannino DM, Aguayo SM, Petty TL, Redd SC. Low lung function and incident lung cancer in the United States: data From the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1475–1480. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Christmas T, Black PN, Metcalf P, Gamble GD. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:380–386. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00144208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koshiol J, Rotunno M, Consonni D, et al. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Altered Risk of Lung Cancer in a Population-Based Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabro E, Randi G, La Vecchia C, et al. Lung function predicts lung cancer risk in smokers: a tool for targeting screening programs. Eur Respir J. 2009 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00049909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petty TL. Are COPD and lung cancer two manifestations of the same disease? Chest. 2005;128:1895–1897. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Whittington CF, Hay BA, Epton MJ, Gamble GD. Individual and cumulative effects of GWAS susceptibility loci in lung cancer: associations after sub-phenotyping for COPD. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houghton AM. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrc3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon PM, Kong CY, Gazelle GS. Model profiler of the MGH-ITA Lung Cancer Policy Model. Available from URL: www.cisnet.cancer.gov/profiles.

- 15.McMahon PM, Kong CY, Johnson BE, et al. Estimating long-term effectiveness of lung cancer screening in the Mayo CT screening study. Radiology. 2008;248:278–287. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMahon PM, Kong CY, Bouzan C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of computed tomography screening for lung cancer in the United States. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1841–1848. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822e59b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon PM, Kong CY, Weinstein MC, et al. Adopting helical CT screening for lung cancer: potential health consequences during a 15-year period. Cancer. 2008;113:3440–3449. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seer*Stat software version 7.0.9, database: Incidence – SEER 18 Regs Research, Nov 2011 Submission, Vintage 2009 Pops (2000-2009) Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; [Accessed June 27, 2012]. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. www.seercancer.gov. released April 2012 based on November 2011 submission. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meza R, ten Haaf K, Kong CY, et al. Comparative analysis of 5 lung cancer natural history and screening models that reproduce outcomes of the NLST and PLCO trials. Cancer. 2014;120:1713–1724. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong CY, McMahon PM, Gazelle GS. Calibration of disease simulation model using an engineering approach. Value Health. 2009;12:521–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. The Framingham Offspring Study. Design and preliminary data. Prev Med. 1975;4:518–525. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(75)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Givelber RJ, Couropmitree NN, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Segregation analysis of pulmonary function among families in the Framingham Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1445–1451. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9704021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:948–968. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipsitz SR, Fitzmaurice GM, Orav EJ, Laird NM. Performance of generalized estimating equations in practical situations. Biometrics. 1994;50:270–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, et al. The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology. 2011;258:243–253. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold M, Siegel J, Russell L, Weinstein M. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shavelle RM, Paculdo DR, Kush SJ, Mannino DM, Strauss DJ. Life expectancy and years of life lost in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Findings from the NHANES III Follow-up Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:137–148. doi: 10.2147/copd.s5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1683–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin K, Watkins B, Johnson T, Rodriguez JA, Barton MB. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using spirometry: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:535–543. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young RP, Hopkins RJ. A clinical practice guideline update on the diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:68–69. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00021. author reply 69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood DE, Eapen GA, Ettinger DS, et al. Lung cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:240–265. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young RP, Hopkins RJ. Diagnosing COPD and targeted lung cancer screening. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1063–1064. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00070012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Balkan A, et al. Association of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:738–744. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-435OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de-Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, et al. Exploring the impact of screening with low-dose CT on lung cancer mortality in mild to moderate COPD patients: a pilot study. Respir Med. 2013;107:702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young RP, Hopkins RJ. CT screening in COPD: impact on lung cancer mortality: de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM et al. Exploring the impact of screening with low-dose CT on lung cancer mortality in mild to moderate COPD patients: a pilot study. Respir med 2013; 107: 702-707. Respir Med. 2014;108:813–814. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de-Torres JP, Zulueta JJ. Response to “Exploring the impact of screening with low-dose CT on lung cancer mortality in mild to moderate COPD patients”. Respir Med. 2014;108:815. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Revised 2014 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Available from URL: http://www.goldcopd.org/

- 39.Shirtcliffe P, Weatherall M, Marsh S, et al. COPD prevalence in a random population survey: a matter of definition. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:232–239. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00157906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meza R, Ten Haaf K, Kong CY, et al. Comparative analysis of 5 lung cancer natural history and screening models that reproduce outcomes of the NLST and PLCO trials. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, et al. Benefits and Harms of Computed Tomography Lung Cancer Screening Strategies: A Comparative Modeling Study for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013 doi: 10.7326/M13-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papi A, Casoni G, Caramori G, et al. COPD increases the risk of squamous histological subtype in smokers who develop non-small cell lung carcinoma. Thorax. 2004;59:679–681. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.018291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Purdue MP, Gold L, Jarvholm B, Alavanja MC, Ward MH, Vermeulen R. Impaired lung function and lung cancer incidence in a cohort of Swedish construction workers. Thorax. 2007;62:51–56. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.