Abstract

We examined the effects of co-cultivated hepatocytes on the hepatospecific differentiation of murine embryonic stem (ES) cells. Utilizing an established mouse ES cell line expressing high or low levels of E-cadherin, that we have previously shown to be responsive to hepatotrophic growth factor stimulation (Dasgupta et al., 2005. Biotechnol Bioeng 92(3):257–266), we compared co-cultures of cadherin-expressing ES (CE-ES) cells with cultured rat hepatocytes, allowing for either paracrine interactions (indirect co-cultures) or both juxtacrine and paracrine interactions (direct co-cultures, random and patterned). Hepatospecific differentiation of ES cells was evaluated in terms of hepatic-like cuboidal morphology, heightened gene expression of late maturation marker, glucose-6-phosphatase in relation to early marker, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and the intracellular localization of albumin. Hepatocytes co-cultured with growth factor primed CE-ES cells markedly enhanced ES cell differentiation toward the hepatic lineage, an effect that was reversed through E-cadherin blockage and inhibited in control ES cells with reduced cadherin expression. Comparison of single ES cell cultures versus co-cultures show that direct contact co-cultures of hepatocytes and CE-ES cells maximally promoted ES cell commitment towards hepatodifferentiation, suggesting cooperative effects of cadherin-based juxtacrine and paracrine interactions. In contrast, E-cadherin deficient mouse ES (CD-ES) cells co-cultured with hepatocytes failed to show increased G6P expression, confirming the role of E-cadherin expression. To establish whether albumin expression in CE-ES cells was spatially regulated by co-cultured hepatocytes, we co-cultivated CE-ES cells around micropatterned, pre-differentiated rat hepatocytes. Albumin localization was enhanced “globally” within CE-ES cell colonies and was inhibited through E-cadherin antibody blockage in all but an interfacial band of ES cells. Thus, stem cell based cadherin presentation may be an effective tool to induce hepatotrophic differentiation by leveraging both distal/paracrine and contact/juxtacrine interactions with primary cells of the liver.

Keywords: embryonic stem cell, liver, E-cadherin, co-culture, hepatocyte, differentiation

Introduction

Embryonic stem (ES) cells afford a promising source of hepatocytes given their unlimited proliferative and pluripotent differentiative capacity (Fuchs and Segre, 2000; Gonzalez-Reyes 2003; McKay 2000; Orkin, 2000). However, this is a highly inefficient and difficult process to control, and the resulting differentiated cells represent heterogeneous populations. Thus, there is a significant motivation to identify organotypic molecular cues that can rapidly differentiate ES cells into hepatic-like cells with phenotypic markers seen in adult hepatocytes. A major source of differentiating cues that remains to be systematically exploited for ES cellular engineering arises from cell–cell interactions(Ball et al., 2004; Bhatia et al., 1998b, 1999; Brieva and Moghe, 2001; Kii et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2007).

There are several instances of cell–cell contact based signaling providing important cues for the development, morphogenesis, and phenotypic stabilization of immature or embryonic cells (Lamy et al., 2000; Rudy-Reil and Lough, 2004; Soto-Gutierrez et al., 2007; Sui et al., 2003). Fetal liver cells acquire differentiated hepatic characteristics in response to soluble factors in conjunction with signals generated from cell–cell contacts. Pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) seem to require heterotypic signaling due to cell–cell contacts with bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) in order to proliferate (Nakamura et al., 1999). Moreover, direct contact between hepatocytes and BMSCs was shown to promote the proliferation of BMSCs by an order of magnitude (Mizuguchi et al., 2001). The growth of HSCs exposed to BMSCs was suggested to result from direct cell-cell and cell–matrix interactions (Koller et al., 1997) and cytokine-mediated signaling (Prockop, 1997; Weimar et al., 1998). Mitaka et al. (1999) cultured small hepatocytes (Shs) with BMSCs and reported hepatocyte proliferation was not regulated in a paracrine manner, but that direct contact was needed to enhance proliferation and differentiation. This highlights the importance of direct cell–cell contact and cell– matrix interaction required for successful differentiation of ES cells into hepatic-like cells in addition to induction of hepatocyte function in vitro (Kamiya et al., 2002). Cell–cell contacts are critical for the development of ES cells during the morphologic events that accompany embryogenesis in vivo, as well as during culture in vitro. Additionally, cell– cell interactions have been shown to play a critical role in tissue generation in vitro (Albrecht et al., 2006).

For this reason, a high degree of cell–cell interactions is crucial for the ES cell differentiation process. Studies comparing fetal liver-derived hematopoietic ES cells cultured using conditioned media (from adult astrocytes) to ES cells grown in direct co-culture have shown that direct cell–cell contact/interactions were necessary to efficiently drive and induce cell differentiation (Hao et al., 2003). Furthermore, insights have shown that stage-dependent tissue play an important role in the ES cell differentiation process (Yoshimizu et al., 2001). Numerous other studies have revealed that co-cultured ES cells have shown enhanced cell lineage differentiation. Specifically, Buttery et al. (2001) observed enhanced differentiation of ES cells toward the osteoblast lineage through supplementing media with growth factors (ascorbic acid, beta-glycerophosphate, dexamethasone (DEX)/retinoic acid (RA)) or through co-culture with fetal murine osteoblasts (Buttery et al., 2001). In fact, the fetal osteoblasts provided a potent stimulus for osteogenic differentiation inducing a fivefold increase in nodule number relative to ES cells cultured alone (Buttery et al., 2001). Additionally, adrenal medullary chromaffin cells provided a supportive microenvironment for neural progenitor cells. Growth and differentiation of neural progenitor cells were compared to standard neural growth media, neural growth media with FGF-2, or co-cultured with bovine chromaffin cells. Survival was poor in the absence of FGF-2 whereas the chromaffin cell co-culture systems promoted robust neurospheres with enhanced mature phenotype. Consequently, the chromaffin cells provided a conducive environment for the survival and neuronal differentiation of neural progenitor cells; they provide a useful, sustained source of trophic support to improve the outcome of neural stem cell transplantation (Schumm et al., 2002). Furthermore, Schwann cell co-cultures were shown to promote the differentiation of rat embryonic neural stem cells highlighting that importance of the factors secreted by Schwann cells and more importantly, that direct cell contact needed to enhance differentiation (Wan et al., 2003). In hepatic systems, Fair et al. (2003) have shown hepatic differentiation induction in ES cells by co-culture with embryonic cardiac mesoderm (Fair et al., 2003). They suggested that embryonic cardiac mesoderm activated crucial transcription factors (Sox 17alpha, HNF3beta and GATA 4) required for hepatic development and notably critical cell–cell interactions were necessary to enhance hepatic differentiation (Fair et al., 2003).

As such, cell–cell interactions have been reported to be important, however the key adhesion mediator, E-cadherin, involved in these interactions has not been systematically examined. Our previous work have highlighted that E-cadherin engineered ES cells exhibited hepatospecific maturation responsiveness to hepatotrophic stimulation (Dasgupta et al., 2005). Furthermore, Brieva and Moghe (2001) have shown that paracrine and juxtacrine signals are important for inducing functional behavior in hepatocytes (Brieva and Moghe, 2001). This current study aims to examine the role of E-cadherins in the differentiation of ES cells using a simple organotypic co-culture model. Our major hypothesis is that primary adult hepatocytes can induce hepatospecific maturation of primed ES cells through two signaling mechanisms related to cadherins: juxtacrine signaling (initiated through cadherin–cadherin contacts between CE-ES and hepatocytes) and paracrine signaling (distally initiated by hepatocytes; mediated by cadherin-growth factor signaling pathways). To identify the optimal co-culture configurations that maximally promote hepatodifferentiation of ES cells, we established co-cultures of rat adult hepatocytes and hepatotrophically stimulated CE-ES cells using two different co-culture configurations: (a) indirect co-culture through insert wells to assess effects of paracrine interactions; (b) direct co-cultures to assess combined paracrine and juxtracrine interactions. Additionally, we employed micropatterned co-cultures to determine whether ES cell differentiation varies with distance from spatially organized hepatocyte cultures.

Materials and Methods

ES Cell Culture Conditions

Mouse embryonic stem cell lines (D3) were utilized (Larue et al., 1996): wild-type homozygous cadherin-expressing embryonic stem (CE-ES) cells, which express high levels of E-cadherin and cadherin-deficient embryonic stem (CD-ES) cells, which are genetically modified by two rounds of homologous recombination to yield null E-cadherin ES cells. A full characterization of the CD-ES and CE-ES cells can be found in our previous publication (Dasgupta et al, 2005). ES cells were cultured on 0.1% (w/v) gelatin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) coated tissue culture polystyrene plates (TCPS). Undifferentiated cells were maintained on knockout Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (KDMEM, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) with high glucose (Invitrogen Corp.), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen Corp.), 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Cambrex BioScience, Walkersville, MD), 2 mM glutamine (Biowhitaker, Walkersville, MD), 1,000 U/mL leukemia inhibiting factor (LIF) ESGRO (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and 2,beta-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen Corp.). Cells were split every 6–7 days with 0.25% Trypsin/0.02% EDTA solution (Sigma) and media were exchanged every other day (Larue et al, 1996).

Initiation of ES Cell Differentiation

The Hanging Drop method was utilized to initiate embryoid body (EB) formation (Hamazaki et al, 2001; Metzger et al, 1994). The EBs were allowed to form over 18 days, which elicited the outgrowth of cells of the hepatocytic lineage from the EB (Dasgupta et al, 2005). Briefly, hang-drop culture media consisted of Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) (Cellgro, Herndon, VA), 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen Corp.), 4 mM l-glutamine (Biowhitaker), and 100 U/mL Penicillin/Streptomycin (Biowhitaker). Cells were diluted to 9.9 × 104 cells/mL; 30 µL drops were placed on the inside of a polystyrene petri dish lid spaced at least 1 cm apart. To ensure gas exchange, 5 mL of basal media was placed on the bottom petri dish lid and the cells were incubated (37°C, 5% CO2, 2 days). On day 2, the EBs were transferred to a new 100 mm petri dish and incubated for two more days. At day 4, single EBs were transferred to TCPS plates and incubated for 7 days. Media were exchanged and cultures incubated for 6 more days. At day 18 (E18), differentiating cells emanating out of the EB were harvested (Hu et al, 2004) by trypsinization and plated onto adsorbed collagen (0.26 mg/mL, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) plates. The sub-population of ES cells were cultured for 1 week either under no cocktail growth medium: basal C+H media or under DOH cocktail growth medium: DEX-OSM-HGF (dexamethasone (DEX): 10−7 M, oncostatin M (OSM): 10 ng/mL, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF): 20 ng/mL) (Sigma) (Kamiya et al., 1999, 2001; Kinoshita and Miyajima, 2002). C + H culture medium is composed of DMEM containing 200 U/mL Penicillin/ Streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen Corp.), 0.5 U/mL insulin, 7 ng/mL glucagon, 7.5 µg/mL hydrocortisone and 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (Sigma). In medium containing DEX, no glucagon was added as they compete for the same receptor. ES cells were grown for 1 week to prime the cells, harvested and replated under co-culture conditions in C+H media (ES cells alone, indirect or direct contact) for an additional week to mimic organotypic environments. Subsequent morphogenesis and hepatogenesis were examined.

Primary Adult Cell Isolation and Culture

Hepatocytes were freshly isolated from Fisher male rats (75–250 g) anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine cocktail. A modified EDTA and collagenase perfusion protocol (Berhiaume et al, 1999; Seglen, 1976) was utilized. Cell suspensions were filtered through nylon meshes with 350 and 62 µm openings (Small Parts, Inc., Miami Lakes, FL). Finally hepatocytes were separated via a Percoll (Sigma) density centrifugation. All animals were maintained and handled in accordance with the Rutgers Institutional Review Board Guidelines for the Use and Care on Animals (Protocol Review Number 97–001). Cell yield and viability (typically 85–92%) were determined via trypan blue exclusion and hemocytometry. Cells were resuspended into DMEM (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen Corp.), epidermal growth factor (EGF, 20 ng/mL: Sigma), insulin (18.5 µg/mL: Sigma), hydrocortisone (7.5 µg/mL: Sigma), glucagon (7 ng/mL: Sigma), 2 mM l-glutamine (Cambrex BioScience), 200 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Cambrex BioScience) and gentamycin (50 µg/mL, Cambrex BioScience); (C + H medium). Isolated hepatocytes were seeded at 2.66 × 104 cells/cm2 onto adsorbed collagen (0.26 mg/mL, BD Biosciences) plates.

Co-Cultures of Cadherin-Engineered ES Cells and Hepatocytes

Co-cultures of primary adult hepatocytes with expanded ES cells were conducted to investigate the effect of indirect (paracrine signaling) and direct (paracrine and juxtacrine signaling) contact driven cues to promote hepatodifferentiation. To conduct indirect co-culture experiments, hepatocytes were seeded on the insert wells (BD Biosciences) with 0.22 µm filters on collagen-coated membranes with the ES cells seeded below on the culture plates, identical in size and surface to the direct co-culture conditions. Hepatocytes were seeded with a volume of 400 µl/well at the same seeding densities (2.66 × 104 cells/cm2) for both indirect and direct co-culture experiments. Hepatocytes were allowed to attach for 10 h and cell medium exchanged, after which the expanded ES cells (subjected to cocktail or no cocktail medium) were harvested and plated down in the co-culture systems at a seeding density of 9.4 × 104 cells/cm2.

Real-Time Reverse-Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis

Total RNA was extracted by using an RNEasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized from 5 µL total RNA by using Superscript II first-strand synthesis with oligo dT (Promega) (48°C, 45 min, first strand synthesis; 94°C, 2 min, RT inactivation/denaturation). PCR was performed using SYBR green PCR master mix (Qiagen). Primers were synthesized for the following mouse genes as per (Hamazaki et al., 2001). The forward and reverse primers were located at different exons to discriminate the product from the targeted mRNA or its genomic DNA. Mouse oligonucleotide sequences are given in brackets in the order of antisense, sense primers followed by annealing temperature, cycles used for PCR and length of amplified fragment: (i) α-fetoprotein (AFP) (5′TCGTATTCCAACAGGAGG, 5′ AGG-CTTTTGCTTCACCAG; 55°C, 25 cycles, 173 bp); (ii) glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P) (5′ CAGGACTGGTTCA-TCCTT, 5′ GTTGCTGTAGTAGTCGGT, 55°C, 30 cycles, 206 bp); (iii) Endogenous housekeeping gene, β-actin (5′ TTCCTTCTTGGGTATGGAAT, 5′ GAGCAATCATC-TTGATCTTC, 55°C, 20 cycles, 200 bp). The gene expression of the intermediate differentiation marker, albumin, was not included in the analysis as, similar to our previous studies, it was not consistently detectable during the onset of hepatospecific differentiation (Dasgupta et al., 2005). The localization of the gene protein product, albumin, however, does vary more consistently and was quantified (described later). Statistical analysis was completed by single variable ANOVA followed by multiple comparison testing.

E-Cadherin Antibody Blocking

Since CD-ES cells are inherently different from CE-ES cells even prior to co-culture, alternative control conditions were employed based on antibody blockage to determine the extent of E-cadherin mediated hepatic differentiation. Expanded CE-ES cells were pretreated with antibodies against E-cadherin prior to introduction with adult hepatocytes in co-culture to confirm that E-cadherins mediate the functional enhancement seen in direct co-culture. Primed CE-ES cells were trypsinized after 1 week of DOH treatment post EB development and exposed to rat anti-E-Cadherin (mouse) ECCD-1 IgG2b monoclonal antibody (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA). A rat IgG2b isotype control antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was used to confirm functionality of antibody blockage. Both antibodies were prepared without preservatives and used at a concentration of 200 µg/mL. The ECCD-1 E-cadherin antibody was chosen because it recognizes E-cadherin on the surface of mouse ES cells to inhibit E-cadherin-dependent cell–cell contacts. CE-ES cell populations were incubated with the E-cadherin or control antibodies for 1 h at 4°C. The cells were washed to remove excess antibody and reconstituted in C + H media. The antibody blocked CE-ES cells were subsequently plated with freshly isolated hepatocytes in identical concentrations to the direct co-culture, as described above. Additionally, a non-antibody treated direct co-culture was included for direct comparison. Media was changed on day 3 and re-supplemented with antibodies to functionally block proliferating mouse ES cells. At 1 week in random co-culture, cells were prepared for RT-PCR, as described above. Statistical analysis was completed by ANOVA with Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD method.

Micropatterned Co-Cultures of ES Cells and Hepatocytes

The fabrication of silicon wafers was carried out as per Folch et al. (2000). Elastomeric PDMS solution (vacuum treated to remove air bubbles) was placed on the silicon wafer and cured overnight at 56°C. The following day, the cured PDMS was carefully peeled off creating elastomeric stamp to pattern cells. The resulting elastomeric stamp provides a robust and reproducible method to micropattern freshly isolated hepatocytes. This novel application uses an elastomeric stamp to preserve cells within the channel microenvironment to pattern hepatocytes. The ability to physically entrap the cells within the feature channel (110 µm height) microenvironment allows for the cells to remain healthy and confined for subsequent cell seeding. Briefly, the stamp is soaked in ethanol for 30 min and allowed to dry, then soaked in bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 10 min to reduce cellular attachment. Hepatocytes were incubated (1 h, 37°C) with 1 µM Cell Tracker Red (Invitrogen Corp.) and washed twice with C + H media to later visibly distinguish the ES cells from hepatocytes in co-culture. Hepatocytes in media (1 mL) were seeded (4.5 × 106 cells/mL) onto a collagen adsorbed (0.26 mg/mL) glass bottom chamber (area = 4 cm2). The elastomeric stamp was quickly placed atop the hepatocytes and weighed with a 50 g metal cylinder. The system was incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48 h. The weight and stencil were carefully removed without disturbing the patterned cells. Wells were washed three times with sterile PBS to remove unattached cells. (The metabolic activity of patterned hepatocytes was independently verified. Stamp-overlaid hepatocytes exhibited slightly elevated albumin secretion rate (0.6 pg/cell/d) in relation to unpatterned hepatocytes (0.4 pg/cell/d), and normal urea secretion rates (7 pg/cell/d) in relation to unpatterned hepatocytes (4.5 pg/cell/d).) The mouse ES cells, primed and isolated post-DOH treatment, were then directly seeded into the chambers to allow for complementary cell attachment. ES cells were subsequently seeded at 9.4 × 104 cells/cm2 around the attached hepatocytes in C + H media. Similar to the direct random co-culture, functional E-cadherin antibody blocking was conducted on the micropatterned co-cultures. Media was exchanged every day and cells were co-cultured for 1 week.

Visualization of Intracellular Albumin

ES cells were stained for the presence of intracellular protein, albumin (hepatic specific marker) to visually confirm that the cells were in fact hepatic-like. For the indirect co-culture conditions, the hepatocyte-containing insert wells were removed immediately prior to analysis. ES cells and hepatocyte co-cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in DPBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were then rapidly washed three times with DPBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Saponin (SAP, Sigma) for 5 min at room temperature. After washing once with DPBS, cells were blocked with 3% (w/v) bovine albumin serum (BSA) and 1% (v/v) normal goat serum (NGS) for 30 min at room temperature to reduce nonspecific antibody binding (Maguire et al, 2006). Subsequently, albumin staining was attained by using FITC-conjugated mouse anti-albumin antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) in SAP buffer (0.5% Saponin, 1% BSA, 0.1% Sodium Azide) for 1 h, rocking at room temperature, at a dilution of 1:50. Finally, the cells were washed four times in DPBS and visualized using the Leica TCS.SP2 confocal microscope system (Leica Microscope, Exton, PA) at 10 × (zoom 2) for random direct and indirect co-cultures and 10 × for micropatterned co-cultures. Albumin staining was quantified by image process analysis (ImagePro 5.0) to quantify the mean green intensity, minus background fluorescence, for an area of interest representing only mouse ES cells, devoid of hepatocytes.

Results

Co-Culture Treatment Altered ES Cell Morphology

The effect of media priming and co-cultivation with hepatocyes on ES cell morphogenesis was evaluated. As shown in Figure 1, beyond day 8 (post EB development and 1 week following ES cell priming), ES cells were basally cultured in C + H growth media or primed in DOH media for a week (day 15). DOH priming was investigated based on our previous work that optimized the growth factor cocktail to induce hepatocyte-like differentiation of mouse ES cells (Dasgupta et al, 2005). CE-ES cells appear cuboidal and cobblestone in appearance, taking on early hepatic cell morphology (Fig. 1A). In contrast, CD-ES cells exhibit very different phenotypic responses. They were elongated, well spread and displayed a fibrotic appearance (Fig. 1E). Priming the CE-ES cells resulted in significantly more cuboidal and cobblestone-like appearance under DOH treatment (Fig. 1B–D). In the presence of direct co-cultures, there is an enhanced degree of cobblestone appearance in CE-ES cells (Fig. 1D). Compact polyhedral cells with round nuclei are visible with well-demarcated cell–cell borders. With indirect co-cultures, the level of cobblestone appearance was not as enhanced compared to direct co-cultures (Fig. 1C). In contrast, as shown in Figure 1F–H, priming ES cells with DOH growth medium did not alter CD-ES cell morphology. This may suggest that priming CE-ES cells affects their morphology either with or without direct contact cues. However, heterotypic cell-cell contacts seem to be important in mediating cellular response, which may be further facilitated through the presence of E-cadherins.

Figure 1.

Morphology of differential cadherin variant ES cells in basal and DOH supplemented media: effect of co-culture configuration. ES cells are cultured alone and within co-culture environments (indirect and direct) with primary adult hepatocytes at day 15. A–D:CE-ES cells, (E–H) CD-ES cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. Magnification 10× (zoom 2), that is, 2× magnification of the original image. CE-ES cells appear distinctly cuboidal, cobblestone phenotypically, whereas CD-ES cells exhibit elongated, fibrotic appearances even under co-culture conditions. CE-ES cells exhibit a greater degree of cobblestone appearance under DOH priming. CD-ES cells continue to exhibit elongated and fibrotic phenotypes.

Elevated Presence of Hepatic Maturation Marker Through Direct Contact Co-Cultures

Expression of hepatic specific markers in the varying ES cell treatments was assessed to reveal the level of hepatic maturation. Specifically, mRNA expression of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP; early hepatic marker), glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P; late hepatic marker) and beta-actin (house-keeping gene) was examined by RT-PCR; each condition was normalized to the level of beta-actin mRNA expression. Hepatocyteonly conditions were also examined to ensure there is no cross-reactivity between rat and mouse genes (data not shown). As shown in Figure 2, normalized AFP was observed in all conditions indicating the presence of immature fetal liver cells, although these levels are not statistically significant when compared to the ES cells alone. The effect of indirect and direct co-culture in CE-ES cells was significant (P < 0.05) for the expression of the late hepatic marker, G6P, compared to CE-ES cells cultured alone in C + H medium (no cocktail) (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, when CE-ES cells were primed in DOH medium (cocktail medium), the effect of indirect co-culture treatment appeared to be insignificant compared to CE-ES cultured alone in DOH medium. This implies that DOH priming can reach gene expression levels similar to those from hepatocyte-conditioned media from insert wells in conjunction with results from Figure 1 showing the enhanced degree of cobblestone appearance associated with DOH priming. Further, there was enhanced expression of G6P in the direct co-culture compared to the other conditions in CE-ES cells. In contrast, there was no significant effect observable for CD-ES cells, either cultured singly or within a co-culture (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Expression of hepatospecific differentiation markers in ES cells: effect of cadherin expression and culture configuration. Effect of co-culture (indirect and direct) condition on CE-ES and CD-ES cells at day 15 (post-EB development plus 1 week ES priming plus 1 week in co-culture C + H media). All cell conditions express some level of AFP indicating the presence of immature fetal liver cells. The effect of indirect and direct co-culture is significant (P < 0.05) for G6P expression (late hepatic marker) compared to the control of CE-ES cells alone in C + H medium (no cocktail). Greater levels of G6P are present in the direct co-culture compared to the other conditions in CE-ES cells. In CD-ES cells, there seems to be no significant effect with or without the presence of co-culture. NOTE: the asterisk denotes significance (P < 0.05) compared to no co-culture (C + H), while # denote significance (P < 0.05) compared to no co-culture DOH condition.

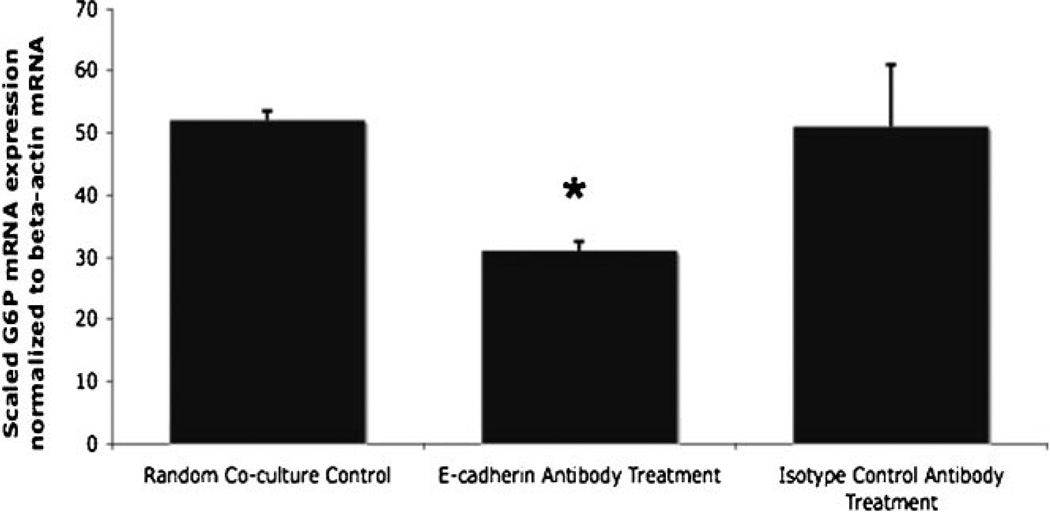

E-Cadherin Blocking Inhibits G6P Based Hepatic Maturation in Direct Co-Culture

CE-ES cells were subjected to E-cadherin antibody blocking to determine the effect of E-cadherin mediated hepatic differentiation in random co-cultures. Results from Figure 2A showed a marked increase in G6P when CE-ES cells were co-cultured with adult hepatocytes. In order to determine if E-cadherin mediated contacts were the cause of this hepatic maturation, we probed for G6P levels in E-cadherin blocked cultures. Real time RT-PCR results (Fig. 3) from the blocking experiments showed that G6P, a late hepatic marker, had statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) when comparing the untreated, direct co-culture to the ECCD-1 E-cadherin antibody blocked co-culture. This data confirms that in random co-cultures, G6P based hepatic maturation is mediated through E-cadherin pathways. The isotype control antibody showed no statistical significance when compared to the direct random co-culture.

Figure 3.

Glucose-6-phosphatase (G6P) expression following antibody blockage of E-cadherin. Effect of E-cadherin blocking in direct co-culture on CE-ES cells at day 15 (post-EB development plus 1 week DOH priming plus 1 week C + H treatment with hepatocytes). The effect of ECCD-1 E-cadherin antibody blocking is significant (P < 0.05) for G6P expression (late hepatic marker) compared to the control untreated direct co-culture. The isotype control antibody blocking is not statistically significant when compared to the random direct co-culture. Asterisk denotes significance (P < 0.05) compared to random co-culture.

Co-Cultured Hepatocytes Promoted ES Cell Morphology and Albumin Expression

To further characterize the hepatic maturation of DOH primed cultures, CD-ES and CE-ES cells were stained at day 15 (post EB 18, plus 1 week ES cell priming by DOH, plus 1 week in co-culture treatment) for intracellular albumin (liver-specific marker) to evaluate whether they were exhibiting hepatic-like behavior. The mouse intracellular albumin antibody has cross-reactivity to rat hepatocytes in our hepatocyte only controls, which is why we chose to prestain the hepatocytes with cell-tracker red to allow the ES cells to be distinguished from hepatocytes in all co-culture experiments. Because of this antibody cross-reactivity issue, we did not seek to detect global albumin secretion levels but instead, we used immunolocalization to evaluate the relative levels of albumin protein in areas devoid of hepatocytes. In Figure 4C and F co-localization of intracellular albumin with cell tracker red in hepatocytes was observed. CD-ES cells showed a slight increase in intracellular albumin staining (Fig. 4A – C) when introducing paracrine signaling (indirect co-culture) and the combination of paracrine and juxtacrine (direct co-culture) signaling. As shown in Figure 4D–F, intracellular albumin staining was observed in CE-ES cells alone and in indirect and direct treatments for randomly seeded hepatocyte co-cultures involving CE-ES cells. CE-ES cells alone exhibited detectable, but not prominent albumin staining. Albumin staining became more pronounced within co-cultures with more prominent and clearly visible staining in direct co-cultures. Results show that combined juxtacrine and paracrine signaling in direct co-cultures, mediated through E-cadherin engagement, significantly increases hepatospecific differentiation.

Figure 4.

Intracellular albumin staining in cadherin-variant ES cells in single ES cultures or random co-cultures with hepatocytes. Intracellular albumin staining in cadherin-variant ES cells at day 15 (post-EB development with 1 week DOH priming plus 1 week in co-culture C + H media) revealed that the degree of albumin staining increased under co-culture conditions (B,C and E,F) compared to ES cells grown alone (A and D). Furthermore, the intensity of albumin staining was most prominent under direct co-culture treatment (F) suggesting that the heterotypic interface is important in mediating cell signaling. Yellow cells in images (C and F) indicate hepatocytes pre-stained with cell tracker red, co-localized with albumin staining. Images were acquired under 20×, scale bar indicates 75 µm. [Color figure can be seen in the online version of this article, available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

The randomly mixed co-cultures of ES cells and hepatocytes do not allow controlled examination of albumin localization across the heterotypic interface between the two cell types. Therefore, cadherin-variant ES cells were separately seeded onto and co-cultured with primary adult hepatocytes, which were first micropatterned. Cell patterning was successfully established through utilization of elastomeric stamps (Fig. 5A and B) with red cell-tracked hepatocytes initially seeded onto the surface. The following day, the stamp was peeled off, carefully leaving patterned hepatocytes (Fig. 5C), and washed to remove unattached cells. Subsequently, cadherin-variant ES cells were seeded in co-culture. At day 2 of co-culture, hepatocytes spread out readily while ES cells proliferated. As shown in Figure 5G–I, there was an increased level of albumin staining (quantified on a confocal microscope using densitometry after subtracting background; mean green intensity = 87.62) in the cultures directly supporting E-cadherin engagement. In contrast, the cadherin deficient co-cultures show lack of albumin staining (mean green intensity = 5.81) in the ES cells (Fig. 5D – F). These results are similar to the cadherin-expressing co-cultures supplemented with an antibody used to functionally block E-cadherin engagement (mean green intensity = 8.99) (Fig. 5J – L). The images provide a direct comparison of the levels of albumin associated with cadherin-variant ES cells in micropatterned co-cultures compared to the ES cells cultured alone or random co-culture (mean green intensity = 60.15). The micropatterning showed observable levels of albumin present in cultures with CE-ES cells and lacking in cultures with CD-ES cells. It is also worth noting that while we did not detect appreciable spatial variations in albumin expression in the CE-ES cultures away from the hepatocyte interface, the cadherin blockage elicited a heterogeneous albumin expression (44.2 intensity units in the nearly 50 µm region near the interface vs. 8.99 units distal to the interface).

Figure 5.

Micropatterned co-cultures of ES cells with primary hepatocytes. Micropatterned co-cultures were established using elastomeric stamps, where ES cells (indicated with arrows) are stained with FITC-conjugated intracellular albumin and hepatocytes were pre-stained with Cell Tracker Red. A and B: Transmitted and SEM images of elastomeric stamp. C: Image of micropatterned hepatocytes. D–L: Images of intracellular albumin staining overlayed with cell tracker red hepatocytes at day 2 of co-culture in C + H media (post-EB development with 1 week DOH priming). Yellow color in merged images indicates hepatocytes, while green alone indicates mouse ES-specific albumin staining. Numbers on the images indicate mean, background-subtracted green intensity corresponding to albumin expression. Intracellular albumin staining is prominent in the co-cultures of CE-ES cells and primary rat hepatocytes (G–I). In contrast, the CD-ES cells (D–F) uniformly lack intracellular albumin staining while the E-cadherin blocked CE-ES cells (J–L) lack intracellular albumin in all regions except those near the hepatocyte interface.

Results from RT-PCR and intracellular albumin staining for the key culture conditions (except micropatterned co-cultures) are summarized in tabular format in Table I. Briefly, growth factor stimulation (DOH) alone is not adequate to promote significant hepatic differentiation in ES cells cultured singly, but does induce morphological differences in terms of a cobblestone appearance. Therefore, DOH treatment was utilized in all subsequent cultures to prime the ES cells. Paracrine stimulation via indirect co-culture supports hepatic differentiation in co-cultures expressing E-cadherins, whereas cadherin-deficient co-cultures do not or minimally increases differentiation, confirmed by albumin protein expression. Direct co-cultures, capturing juxtacrine and paracrine signaling, moderately increase differentiation through albumin protein expression in cadherin-deficient cultures and significantly increase differentiation measured in terms of G6P gene expression and albumin protein expression in E-cadherin-expressing environments. Combined, these results show that E-cadherin engagement is sufficient to promote hepatic differentiation when ES cells are optimally primed and co-cultured with differentiated hepatocytes.

Table I.

Summary of hepatotrophic stimulation of ES cell differentiation.

| Growth factor stimulation |

Indirect co-culture |

Direct co-culture |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD-ES | CE-ES | CD-ES | CE-ES | CD-ES | CE-ES | |

| Hepatospecific morphology | − | + | − | ++ | − | +++ |

| G6P gene expression | − | + | + | ++ | − | +++ |

| Albumin protein expression | − | − | + | ++ | ++ | +++ |

The table shows a graded level of differentiation based on significance for the morphology, RT-PCR results and qualitative levels of albumin expression for immunocytochemistry. Results show that growth factor stimulation is sufficient to produce detectible levels of differentiation in cadherin expressing (CE-ES) cells. Indirect co-culture through paracrine signaling generates intermediate levels of differentiation with G6P expression and albumin protein expression in co-cultures with cadherin-expressing cells and low levels of albumin protein expression in cadherin-deficient (CD-ES) cells. The most significant levels of hepatospecific markers is seen with CE-ES cells in direct co-culture with primary hepatocytes.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine whether hepatocytes can promote hepatospecific differentiation in ES cells and identify the regulatory factors underlying these interactions (ES cell cadherin expression; mode of hepatotrophic interactions in terms of indirect vs. contact stimulation). Our results indicate that enhanced hepatic differentiation of ES cells requires (a) elevated E-cadherin expression, and (b) co-cultures that enable a combination of intimate hepatocyte-ES cell contacts and stimulation from metabolically active hepatocytes.

In culturing the ES cells, a modified hang-drop protocol (Dang et al., 2002; Hamazaki et al., 2001) was utilized to recapitulate embryogenesis and expand cell growth (Dasgupta et al., 2005). After sub-culture at day 18 post-EB (E18), ES cells were grown for 1 week under growth factor cocktail treatment (DEX/OSM/HGF) to help prime the cells for organotypic co-culture or in the absence of the cocktail treatment (just C + H medium). After 1 week of DOH treatment, ES cells were harvested and re-plated in co-culture environments and monitored for a subsequent week (2 weeks E18). CE-ES cell morphology maintained a cuboidal, cobblestone appearance which was indicative of fetal hepatic phenotype (He et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2003; Kuai et al., 2003); however, in the presence of co-culture systems, the degree of hepatic morphology was enhanced: cobblestone, compact polyhedral cells with round nuclei, well demarcated cell–cell borders and the appearance of bile canalicular networks (Bhatia et al., 1999). The effect of priming the cells with DOH and C + H media did not significantly affect cell morphology in CE-ES cells. In CD-ES cells, cell morphology was also not affected by different media treatment or by co-culture presence. CD-ES cells maintained a spread, elongated fibrotic appearance, which persisted throughout conditioning (cocktail/no cocktail) and co-culture condition (indirect/direct).

In probing subsequent genetic expression of ES cells, the effect of no-co-culture versus co-culture (indirect and direct) was compared between both CE-ES and CD-ES cells. Interestingly, priming CE-ES cells with DEX/OSM/HGF (DOH) was able to compensate for the effect arising from indirect co-culture treatment. There was no significant difference in gene expression (AFP/G6P) between these two conditions; however, expression of the late hepatic marker (G6P) was significantly (P < 0.05) different when comparing indirect co-culture to the no priming condition (C + H media that primary hepatocytes are normally cultured in). Possibly the lack of priming makes the CE-ES cells less responsive, while priming ES cells compensates, to some extent, for the cues that hepatocytes secrete. Furthermore, CE-ES cells in direct co-cultures exhibited elevated expression of G6P (P < 0.05) compared to ES cells alone (no-co-cultures). This phenomenon was further proved with the addition of E-cadherin blocking antibodies in random co-culture conditions. To confirm that E-cadherin specifically enhanced ES cells in direct co-culture with hepatocytes, we examined the effects of blocking E-cadherin antibody on ES function through RT-PCR. The addition of a monoclonal antibody against ECCD-1 functionally blocked E-cadherin based adhesion between ES cells and hepatocytes, resulting in diminished levels of G6P when compared to untreated random co-culture. The addition of an isotype control antibody did not have any effect on the functional enhancement. Hence, there seems to be some contact driven cues at the heterotypic interface level that enhances hepatic differentiation/maturation. However, CD-ES cells showed no significant effect from growth factor priming or in co-culture conditions. Previous studies have all highlighted the importance of direct cell–cell contact in driving differentiated phenotype and functional cell abilities (Abouelfetouh et al., 2004; Ball et al., 2004; Bhatia et al., 1998a, 1997; Brieva and Moghe, 2001; Kamei et al., 2004).

In particular, Bhatia et al. (1998a) observed through spatially patterned co-cultures of hepatocyte and fibroblasts that (a) the heterotypic interface between hepatocyte and mesenchymal cells correlates with high levels of differentiation; and (b) for equivalent extent of heterotypic interfaces, differentiation increases with the number of fibroblasts, suggesting that fibroblast homotypic signaling may have a feedback on the hepatocyte environment. Furthermore, with the presence of heterotypic cell–cell contacts being established through E-cadherin engagement, other functional junction contacts may be ameliorated and/or stabilized. Studies have shown that E-cadherin is not only necessary for adherens junction formation but its adhesive activity is also critical for the assembly of other junctional complexes such as desmosomes, gap junctions and tight junctions (Gumbiner, 1996; Watabe et al., 1994). In particular, tight junction (Loreal et al., 1993; Tunggal et al., 2005) and gap junction (Mesnil et al., 1987) interactions may be augmented through the successful cell–cell E-cadherin engagement and stabilization. Tight junction (ZO-1) and gap junction (connexins) assembly ensues with the correct establishment of cell polarity and with proper enrichment of several protein complexes at these cell junctions essential for polarity. This indicates there is an intimate relationship between junction formation and polarity (Nelson, 2003; Tunggal et al., 2005) that can effectively occur through suitable cell–cell engagement, which is mediated through E-cadherins.

The intracellular albumin localization trends of micro-patterned hepatocytes and ES cells may shed some light into how the heterotypic interface may be essential in transmitting important cellular cues. The heterotypic contact may potentially be up-regulating intracellular albumin localization with CE-ES cells in direct contact with hepatocytes. Random co-cultures with hepatocytes showed moderate albumin staining, but the microstamped hepatocytes in particular increased intracellular albumin localization in CE-ES cells. Further, random co-cultures of hepatocytes with cadherin-expressing ES cells resulted in higher hepatic differentiation of ES cells compared to indirect co-cultures through paracrine-conditioned media, pointing to the role of direct cell–cell contacts between ES cells and hepatocytes.

Most of our ES cell co-cultures micropatterned with hepatocytes showed no perceptible variations in albumin localization as a function of spatial distance from the hepatocyte-ES cell interface. This indicates a more global, paracrine regulation of ES cells by hepatocytes. The microstamp-overlaid hepatocytes in our micropatterned co-cultures are metabolically somewhat more functional than monolayer cultured hepatocytes such as those we utilized in our random co-cultures (e.g., urea secretion rates; see Materials and Methods Section) (Berthiaume et al., 1996; Dunn et al., 1989). We believe this factor (increased paracrine and juxtacrine stimulation) may explain why the ES cells in our micropatterned co-cultures expressed greater levels of albumin (86.72 intensity units) than in random co-cultures (60.15 intensity units). It is likely that the combined paracrine and juxtacrine ES cell stimulation by such metabolically active hepatocytes may be masking the role of contact-regulation and reinforcing the global regulation of ES cell differentiation. Indeed in one condition where cadherin antibodies were incorporated into the micro-patterned co-cultures, we observed the first instance of spatial heterogeneity of differentiation responsiveness. Following cadherin blockage, albumin localization in ES cells distal to the hepatocyte interface was inhibited significantly but not that in ES cells immediately adjacent to the hepatocytes, reminiscent of heterotypic spatial variation within co-cultures (Bhatia et al., 1999). This points to the role of cadherin blockage on the inhibition of primarily the homotypic juxtacrine signaling among the mouse ES cells, and secondarily, cadherin-mediated juxtacrine heterotypic contacts between hepatocytes and ES cells. The antibody blockage experiments do not directly block cadherin-triggered paracrine signaling from the rat hepatocytes (as well as cadherin-mediated homotypic signaling in hepatocytes). The unblocked co-culture controls allows for E-cadherin-mediated heterotypic interactions and paracrine signaling emanating from the hepatocytes coupled with the homotypic E-cadherin-mediated interaction between mouse ES cells.

In conclusion, we report that hepatocyte co-cultures with murine embryonic stem cells promote the hepatospecific differentiation of stem cells. Three key factors promote this effect: hepatotrophic priming of stem cells; cadherin expression on stem cells; and microscale contact/proximity to hepatocytes. Identification of the molecular nature of hepatocyte-derived priming of ES cells remains a subject for future investigation. Insights from this study could be relevant to design improved hepatotrophic culture models to differentiate ES cells and yield strategies for integration of transplanted ES cells within the liver milieu for in situ stem cell based tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

PVM gratefully acknowledges support from New Jersey Commission on Science and Technology, NIH EB001046; NSF CAREER Award; NSF DGE 03333196; Rutgers University Academic Excellence Fund and LL is grateful for support to Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (Equipe labellise´e). We would also like to thank Dr. Maria Pia Rossi for the SEM assistance. This study was supported as a collaborative project of the NIH P41 BioMEMS Resource Center at Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School. Rebecca Moore was partially funded by a NSF IGERT Training Program on Integratively Engineered Biointerfaces, while Anouska Dasgupta was supported on a Rutgers/UMDNJ NIH Biotechnology Training Program.

References

- Abouelfetouh A, Kondoh T, Ehara K, Kohmura E. Morphological differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells into neuron-like cells after co-culture with hippocampal slice. Brain Res. 2004;1029(1):114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht DR, Underhill GH, Wassermann TB, Sah RL, Bhatia SN. Probing the role of multicellular organization in three-dimensional microenvironments. Nat Methods. 2006;3(5):369–375. doi: 10.1038/nmeth873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SG, Shuttleworth AC, Kielty CM. Direct cell contact influences bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell fate. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(4):714–727. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhiaume F, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML, editors. Tissue engineering methods and protocols. Totowa: Humana Press; 1999. pp. 447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Berthiaume F, Moghe PV, Toner M, Yarmush ML. Effect of extracellular matrix topology on cell structure, function, and physiological responsiveness: Hepatocytes cultured in a sandwich configuration. FASEB J. 1996;10(13):1471–1484. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.13.8940293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SN, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Controlling cell interactions by micropatterning in co-cultures: Hepatocytes and 3T3 fibroblasts. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;34(2):189–199. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199702)34:2<189::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SN, Balis UJ, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Microfabrication of hepatocyte/fibroblast co-cultures: Role of homotypic cell interactions. Biotechnol Prog. 1998a;14(3):378–387. doi: 10.1021/bp980036j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SN, Balis UJ, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Probing heterotypic cell interactions: Hepatocyte function in microfabricated co-cultures. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1998b;9(11):1137–1160. doi: 10.1163/156856298x00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SN, Balis UJ, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Effect of cell-cell interactions in preservation of cellular phenotype: Cocultivation of hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells. FASEB J. 1999;13(14):1883–1900. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brieva T, Moghe P. Functional engineering of hepatocytes via heterotypic presentation of a homoadhesive molecule, E-cadherin. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;76:295. doi: 10.1002/bit.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttery LD, Bourne S, Xynos JD, Wood H, Hughes FJ, Hughes SP, Episkopou V, Polak JM. Differentiation of osteoblasts and in vitro bone formation from murine embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(1):89–899. doi: 10.1089/107632700300003323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang SM, Kyba M, Perlingeiro R, Daley GQ, Zandstra PW. Efficiency of embryoid body formation and hematopoietic development from embryonic stem cells in different culture systems. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;78(4):442–453. doi: 10.1002/bit.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta A, Hughey R, Lancin P, Larue L, Moghe PV. E-cadherin synergistically induces hepatospecific phenotype and maturation of embryonic stem cells in conjunction with hepatotrophic factors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92(3):257–266. doi: 10.1002/bit.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JC, Yarmush ML, Koebe HG, Tompkins RG. Hepatocyte function and extracellular matrix geometry: Long-term culture in a sandwich configuration [published erratum appears in FASEB J 1989 May; 3(7) 1873] FASEB J. 1989;3(2):174–177. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.2.2914628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair JH, Cairns BA, Lapaglia M, Wang J, Meyer AA, Kim H, Hatada S, Smithies O, Pevny L. Induction of hepatic differentiation in embryonic stem cells by co-culture with embryonic cardiac mesoderm. Surgery. 2003;134(2):189–196. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch A, Jo BH, Hurtado O, Beebe DJ, Toner M. Microfabricated elastomeric stencils for micropatterning cell cultures. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52(2):346–353. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2<346::aid-jbm14>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Segre JA. Stem cells: A new lease on life. Cell. 2000;100(1):143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Reyes A. Stem Cells, niches and cadherins: A view from Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:949–954. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: The molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84(3):345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki T, Iiboshi Y, Oka M, Papst PJ, Meacham AM, Zon LI, Terada N. Hepatic maturation in differentiating embryonic stem cells in vitro. FEBS Lett. 2001;497(1):15–19. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao H, Zhao J, Thomas RL, Parker GC, Lyman WD. Fetal human hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate sequentially into neural stem cells and then astrocytes in vitro. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2003;12(1):23–32. doi: 10.1089/152581603321210109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ZP, Tan WQ, Tang YF, Feng MF. Differentiation of putative hepatic stem cells derived from adult rats into mature hepatocytes in the presence of epidermal growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor. Differentiation. 2003;71(4–5):281–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.7104505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu A, Cai J, Zheng Q, He X, Pan Y, Li L. Hepatic differentiation from embryonic stem cells in vitro. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116(12):1893–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu AB, Cai JY, Zheng QC, He XQ, Shan Y, Pan YL, Zeng GC, Hong A, Dai Y, Li LS. High-ratio differentiation of embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes in vitro. Liver Int. 2004;24(3):237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei N, Oishi Y, Tanaka N, Ishida O, Fujiwara Y, Ochi M. Neural progenitor cells promote corticospinal axon growth in organotypic co-cultures. Neuroreport. 2004;15(17):2579–2583. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200412030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Kinoshita T, Ito Y, Matsui T, Morikawa Y, Senba E, Nakashima K, Taga T, Yoshida K, Kishimoto T, et al. Fetal liver development requires a paracrine action of oncostatin M through the gp130 signal transducer. EMBO J. 1999;18(8):2127–2136. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Kinoshita T, Miyajima A. Oncostatin M and hepatocyte growth factor induce hepatic maturation via distinct signaling pathways. FEBS Lett. 2001;492(1–2):90–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Kojima N, Kinoshita T, Sakai Y, Miyaijma A. Maturation of fetal hepatocytes in vitro by extracellular matrices and oncostatin M: Induction of tryptophan oxygenase. Hepatology. 2002;35(6):1351–1359. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kii I, Amizuka N, Shimomura J, Saga Y, Kudo A. Cell-cell interaction mediated by cadherin-11 directly regulates the differentiation of mesenchymal cells into the cells of the osteo-lineage and the chon-dro-lineage. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(11):1840–1849. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Miyajima A. Cytokine regulation of liver development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1592(3):303–312. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller MR, Manchel I, Palsson BO. Importance of parenchymal:-stromal cell ratio for the ex vivo reconstitution of human hematopoiesis. Stem Cells. 1997;15(4):305–313. doi: 10.1002/stem.150305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuai XL, Cong XQ, Li XL, Xiao SD. Generation of hepatocytes from cultured mouse embryonic stem cells. Liver Transpl. 2003;9(10):1094–1099. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamy I, Corlu A, Guguen-Guillouzo C. Differentiation of hepatic and hematopoietic stem cells: Study of liver regulation protein (LRP) Ann Pharm Fr. 2000;58(4):260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larue L, Antos C, Butz S, Huber O, Delmas V, Dominis M, Kemler R. A role for cadherins in tissue formation. Development. 1996;122(10):3185–3194. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Lu M, Tian X, Han Z. Molecular mechanisms involved in self-renewal and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211(2):279–286. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreal O, Levavasseur F, Fromaget C, Gros D, Guillouzo A, Clement B. Cooperation of Ito cells and hepatocytes in the deposition of an extracellular matrix in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1993;143(2):538–544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire T, Novik E, Schloss R, Yarmush M. Alginate-PLL microencapsulation: Effect on the differentiation of embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;93(3):581–591. doi: 10.1002/bit.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay R. Stem cells—Hype and Hope. Nature. 2000;406:361–364. doi: 10.1038/35019186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnil M, Fraslin JM, Piccoli C, Yamasaki H, Guguen-Guillouzo C. Cell contact but not junctional communication (dye coupling) with biliary epithelial cells is required for hepatocytes to maintain differentiated functions. Exp Cell Res. 1987;173(2):524–533. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger JM, Lin WI, Samuelson LC. Transition in cardiac contractile sensitivity to calcium during the in vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;126(3):701–711. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.3.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitaka T, Sato F, Mizuguchi T, Yokono T, Mochizuki Y. Reconstruction of hepatic organoid by rat small hepatocytes and hepatic nonparenchymal cells. Hepatology. 1999;29(1):111–125. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi T, Hui T, Palm K, Sugiyama N, Mitaka T, Demetriou AA, Rozga J. Enhanced proliferation and differentiation of rat hepatocytes cultured with bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189(1):106–119. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Ando K, Chargui J, Kawada H, Sato T, Tsuji T, Hotta T, Kato S. Ex vivo generation of CD34(+) cells from CD34(−) hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1999;94(12):4053–4059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WJ. Adaptation of core mechanisms to generate cell polarity. Nature. 2003;422(6933):766–774. doi: 10.1038/nature01602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin SH. Stem cell alchemy. Nat Med. 2000;6(11):1212–1213. doi: 10.1038/81303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276(5309):71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy-Reil D, Lough J. Avian precardiac endoderm/mesoderm induces cardiac myocyte differentiation in murine embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2004;94(12):107–116. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134852.12783.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm MA, Castellanos DA, Frydel BR, Sagen J. Enhanced viability and neuronal differentiation of neural progenitors by chromaffin cell co-culture. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;137(2):115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seglen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1976;13:29–83. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Gutierrez A, Navarro-Alvarez N, Zhao D, Rivas-Carrillo JD, Lebkowski J, Tanaka N, Fox IJ, Kobayashi N. Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells to hepatocyte-like cells by co-culture with human liver nonparenchymal cell lines. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(2):347–356. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui Y, Clarke T, Khillan JS. Limb bud progenitor cells induce differentiation of pluripotent embryonic stem cells into chondrogenic lineage. Differentiation. 2003;71(9–10):578–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2003.07109001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunggal J, Helfrich I, Schmitz A, Schwarz H, Gunzel D, Fromm M, Kemle R, Krieg T, Niessen CM. E-cadherin is essential for in vivo epidermal barrier function by regulating tight junctions. EMBO J. 2005;24(6):1146–1156. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H, An YH, Sun MZ, Zhang YZ, Wang ZC. Schwann cells transplantation promoted and the repair of brain stem injury in rats. Biomed Environ Sci. 2003;16(3):212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe M, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Takeichi M. Induction of polarized cell-cell association and retardation of growth by activation of the E-cadherin-catenin adhesion system in a dispersed carcinoma line. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(1):247–256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimar IS, Voermans C, Bourhis JH, Miranda N, van den Berk PC, Nakamura T, de Gast GC, Gerritsen WR. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) affects proliferation and migration of myeloid leukemic cells. Leukemia. 1998;12(8):1195–1203. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimizu T, Obinata M, Matsui Y. Stage-specific tissue and cell interactions play key roles in mouse germ cell specification. Development. 2001;128(4):481–490. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]