Abstract

Objective

To understand if narratives can be effective tools for diabetes empowerment, from the perspective of African-American participants in a program that improved diabetes self-efficacy and self-management.

Methods

In-depth interviews and focus groups were conducted with program graduates. Participants were asked to comment on the program's film, storytelling, and role-play, and whether those narratives had contributed to their diabetes behavior change. An iterative process of coding, analyzing, and summarizing transcripts was completed using the framework approach.

Results

African-American adults (n = 36) with diabetes reported that narratives positively influenced the diabetes behavior change they had experienced by improving their attitudes/beliefs while increasing their knowledge/skills. The social proliferation of narrative – discussing stories, rehearsing their messages with role-play, and building social support through storytelling – was reported as especially influential.

Conclusion

Utilizing narratives in group settings may facilitate health behavior change, particularly in minority communities with traditions of storytelling. Theoretical models explaining narrative's effect on behavior change should consider the social context of narratives.

Practice implications

Narratives may be promising tools to promote diabetes empowerment. Interventions using narratives may be more effective if they include group time to discuss and rehearse the stories presented, and if they foster an environment conducive to social support among participants.

Keywords: Narrative, Behavioral change, Diabetes, Minority health, Culture

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Diabetes affects 25.8 million people in the United States. Racial/ ethnic minorities are disproportionately burdened by the disease: they experience higher prevalence and worse control of diabetes and its comorbid conditions (e.g. hypertension, hyperlipidemia) and higher rates of diabetes-related complications (e.g. kidney disease, blindness) [1–3]. Diabetes patient empowerment has been conceptualized as the patient confidence (i.e. self-efficacy) and skills to engage in self-care activities (e.g. healthy nutrition, physical activity, foot care) as well as shared decision-making (SDM), where patients collaborate with providers to set their diabetes priorities and treatment plans [4,5]. Diabetes self-care activities [1,2,6] and SDM [7,8] are associated with behavior change, diabetes control, and self-reported health. However, racial/ ethnic minorities disproportionately face barriers to diabetes self-care and SDM, including limited access to healthy food and/or exercise facilities, patient/provider communication barriers, and difficulty navigating the healthcare system [9,10]. Identifying effective strategies to empower patients is a national priority, particularly to improve minority health and reduce racial/ethnic diabetes disparities [11].

One effective empowerment strategy in minority populations is storytelling, or narrative [12]. Narrative facilitates processing of new information among those with lower health literacy and/or numeracy [13]. Through storytelling, people discover new self-perceptions or strengths [14], while building trust and connections with peers [15]. Storytelling helps to sustain behavior changes by creating meaning for past events and building an identity to motivate future action [16]. Narrative may be particularly effective in promoting health behavior change among racial/ethnic groups with a strong tradition of storytelling, and those with a history of medical mistrust [12,17,18]. Studies have effectively used narrative with African-Americans [19], Latinos [20,21], and Native Americans [22], to encourage behavior change in hypertension [17,23] tobacco use [24], cancer [25,26], and HIV prevention [27]. The modes of narrative studied vary and include theater performances, testimonials for a live audience, informal group storytelling, television or radio drama, films, and written stories.

Thus, narrative shows promise as a potential method to empower minority patients with diabetes, by promoting self-care and facilitating SDM. Narrative may help diabetes patients learn new information, explore and practice behavior change, build a support network of peers, and communicate effectively with their healthcare team. Indeed, narratives in the form of novellas have been successfully used in diabetes interventions tailored to Hispanic populations [28,29]. For African-Americans with diabetes, being able to tell one's story and “be heard” has been described as a significant component of SDM [30]. To date, the use of narrative has not been explored in urban African-Americans with diabetes, a population widely impacted by racial/ethnic diabetes disparities [1–3].

We investigated how narrative may influence diabetes empowerment in urban African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Our team leads The Diabetes Empowerment Program (DEP), a culturally-tailored patient empowerment intervention associated with improved self-efficacy, diabetes self-management (e.g. healthy eating) and health outcomes (e.g. diabetes and lipid control) [4]. In addition, the DEP has had excellent retention rates: 78% of participants came to 70% of classes, and 38% attended 100% of classes [31]. Anecdotally, patients noted that the narrative components of DEP contributed to their success in making diabetes-related behavior changes. Therefore, we conducted a qualitative study to better understand how former DEP participants perceived the role of narrative in promoting patient empowerment (i.e. self-efficacy, self-care and SDM) [4].

In this paper, we briefly summarize theoretical models explaining narrative's effect, and, as background, illustrate how DEP incorporated narrative into the empowerment intervention. We then describe our qualitative study, the focus of this paper, which aimed to understand how DEP participants perceived the role of narrative in potential behavior change and empowerment. Finally, we return to the theory surrounding narrative's influence and outline the impact our results have on existing models.

1.2. How narrative promotes behavior change

Kreuter defines narrative as “a representation of connected events and characters that has an identifiable structure, is bounded in space and time, and contains implicit or explicit messages about the topic being addressed.” Nonnarrative, in contrast, “includes expository and didactic styles of communication that present propositions in the form of reasons and evidence supporting a claim” [13] (emphasis added).

Predominant models of narrative's influence have historically focused on how individuals personally interact with a narrative [32–35]. In contrast, a recent model proposed by Larkey and Hecht moves beyond the personal level at which one interacts with narrative to also consider the sociocultural level [36]. This approach suggests that health narratives shared by members of a group may help to create more culturally representative health programs [36]. Because culturally-tailored interventions are essential to reducing disparities among minority patients [37], we utilized this model to explore how narrative worked among African-Americans with diabetes.

At the individual level, the Larkey and Hecht model states that when recipients are engaged in a narrative, they are less likely to resist its messages, and the story can impact their attitudes and beliefs [35]. At the sociocultural level, the model adds cultural embeddedness as another persuasive characteristic of narrative. Cultural embeddedness is the extent to which characters, events, and language are similar to participants' experiences, thereby evoking empathy and liking of the characters and events.

According to Larkey and Hecht, engagement and cultural embeddedness impact behavior change via three mediators: (1) transportation; (2) identification; and (3) social proliferation. Transportation is when a recipient is “swept away,” immersed in the story, and it makes recipients more likely to agree with the story's messages [38]. Identification is when recipients are involved with characters, e.g. they may see themselves in the characters, like them, or imagine relationships with them [13,39], and it makes recipients more ready to learn and adopt behaviors modeled by those characters [12].

The addition of social proliferation, Larkey and Hecht's third mediator, reflects the sociocultural level at which they propose narrative influences behavior. Social proliferation is the discussion of stories, the reinforcement of their messages, and the reciprocal support that emerges from sharing them. When recipients share stories, they diffuse the information to new people, “rehearse” the messages by modeling the promoted behavior for each other, and nurture social support for the behavior that encourages its implementation.

It is unclear whether some of these mediators (transportation, identification, and social proliferation) are more influential in different populations. Understanding the different roles these mediators play, and how they vary by patient population, is an important question for designing and implementing narrative interventions that can empower patients and reduce health disparities.

1.3. Narrative in the Diabetes Empowerment Program

Our team, a multi-disciplinary group (with expertise in diabetes, health services research, health disparities, behavioral change, implementation science, diabetes education and social psychology) at the University of Chicago, in partnership with six clinics, leads a multifaceted intervention to improve diabetes on the South Side of Chicago [40], a largely working class, African-American community with significant diabetes disparities. One component of the intervention, the Diabetes Empowerment Program (DEP), is a series of weekly small group classes at participating clinics, which lasts for 10 weeks and is followed by monthly support group meetings. The DEP has been described in detail elsewhere [4]; it combines culturally-tailored diabetes education with training in shared decision-making (SDM). The DEP emphasizes that patients can become empowered to manage their diabetes [41], as they have expertise in their life with diabetes, are problem solvers and caregivers, and can make informed choices. The DEP incorporated 3 types of narrative – film, personal storytelling, and role-play – designed to empower patients by promoting diabetes self-care, SDM, and self-efficacy.

1.3.1. The film

An eleven-minute film is shown to patients twice during the DEP, and features our physician investigator, an African-American woman, explaining SDM and describing her family's story about diabetes treatment decisions. The film also presents two vignettes about diabetes-related SDM. The film is culturally tailored, drawing upon the research team's prior research with African-Americans regarding diabetes and SDM [30,42–45]. It utilizes African-American actors, illustrates cultural food practices, and enacts some of the SDM barriers and facilitators previously identified [42]. The script for the film was created by the DEP principal investigator and iteratively revised using a multi-disciplinary team that included patients, film producers and professionals with expertise in diabetes research, social psychology, diabetes education, nursing, and communication science. After the film, discussion was facilitated using “teachable moments” from the video to discuss shared decision-making.

1.3.2. Personal storytelling

The DEP also incorporates personal storytelling, which reflects the African-American oral tradition of “testifying,” where individuals testify or “witness” to their community, often a church congregation, sharing a personal experience and explaining how that experience affected their life [46]. Other health interventions have drawn on this tradition of testifying to increase health behaviors [46,47]. In the DEP, for example, patients are asked to describe their feelings and experiences when initially diagnosed with diabetes, share how they negotiate food-related interactions with family and friends, and respond to each other's stories with questions, comments, or their own stories.

1.3.3. Role-play

Role-play is used extensively throughout the DEP to promote self-care and SDM skills. For example, patients role-play selecting a healthy meal with local restaurant menus and asking their doctors for more information about treatment options. During role-play, teachers pause to ask the group for suggestions, or to guide the patient participating. Discussion is facilitated afterwards about what went well and what could be improved in the patient's approach.

1.4. Evaluating the use of narrative among African-Americans with diabetes

The DEP's use of narrative is unique in two ways. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use narrative among urban African-American adults with diabetes, and it uses three types of narrative within the same intervention: film, personal storytelling, and role-play.

Given that DEP had enhanced diabetes-related behavior changes in its participants [4], we conducted a qualitative study with former DEP participants to understand: (1) If patients perceived that the narratives contributed to their empowerment and behavior change, and (2) If transportation, identification, and social proliferation were reported mediators of narrative's perceived effect.

2. Methods

We conducted in-depth, in-person, semi-structured interviews and focus groups with former DEP participants at two federally-qualified health centers and one academic medical center. Individual interviews lasted approximately 60 min; focus groups lasted approximately 90 min.

2.1. Patient recruitment

After receiving approval from our institution's research ethics committee (the Institutional Review Board), all DEP graduates were invited to participate in focus groups led by trained moderators not affiliated with the program. Each DEP participant was contacted up to three times by phone and once in writing. Patients received a $20 gift card to a local grocery store as an incentive. Patients interested in participating but unable to attend one of the scheduled focus groups were invited to an individual inperson interview; seven interviews and four focus groups (n = 29) were conducted, at which point theme saturation was met.

2.2. Study instruments

A topic guide was developed by the research team (APG, KER, MEP) in which open-ended questions were accompanied by follow-up probes. Participants were asked to reflect on their time in the DEP and the narratives utilized in class. For example, we asked about general contributors to DEP retention (e.g. “What made the diabetes classes something you were willing to regularly attend?”), transportation and identification (e.g. “What thoughts or emotions did you have while watching this film?” and “Have you ever had any similar experiences?”), and social proliferation (e.g. “How does it make you feel to tell your story?” and “What did you think of the role-playing?”). Focus groups and interviews were conducted until theme saturation was met.

2.3. Analysis

We used the framework approach to guide our analysis. Similar to grounded theory, this analysis is “grounded” in the original accounts of the participants. However, analysis is deductive, originating from predetermined objectives. Thus, the results are clearly defined themes that are grounded in the information provided by participants [48–50].

All interviews and focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three coders independently reviewed and coded the first transcript, then met to discuss the coding and create uniform coding guidelines. Subsequently, each transcript was coded by two of the researchers and results were discussed to consensus. A codebook was iteratively developed, and all coded transcripts were uploaded into Atlas.ti 6 software for theme analysis. The transcripts were divided among the three researchers for in-depth review and thematic analysis. Summaries of final themes in each transcript were drafted by one researcher (APG) and discussed to consensus by the group. In an effort to triangulate the data, we compared codes and themes from the in-person interviews and the focus groups to assess for data consistency. As a validity check, two study participants were asked to review the study results and provide feedback and/or revisions.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Of the 51 Diabetes Empowerment Program participants (at the time of the study), 36 participated in the focus groups or individual interviews (69% participation rate). There were no statistical differences in sociodemographics of DEP participants who enrolled (vs. not) in this qualitative study (Table 1). The mean age of participants was 58 years and 83% were female. Fifty percent of participants had a high school degree or less education, and 60% had annual household incomes under $15,000. Sixty-six percent of participants were insured by Medicare or Medicaid. The mean number of years with diabetes was eight, and, on average, participants had one diabetes complication.

Table 1.

Demographics of DEP participants enrolled vs. not enrolled in narrative study*.

| DEP participants enrolled in narrative study (n = 36) % (absolute number) | DEP participants not enrolled in narrative study (n = 15) % (absolute number) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.43 | ||

| <50 | 25 (9) | 21 (3) | |

| 50–64 | 53 (19) | 71 (10) | |

| >65 | 22 (8) | 7.2 (1) | |

| Female gender | 83 (30) | 60 (9) | 0.07 |

| Marital status | 0.57 | ||

| Single | 47(17) | 33 (5) | |

| Married/living as married | 17 (6) | 27 (4) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 36 (13) | 40 (6) | |

| Education | 1.0 | ||

| Some high school or less | 31 (11) | 33 (5) | |

| High school graduate | 25 (9) | 27 (4) | |

| Some college | 31 (11) | 27 (4) | |

| College graduate or higher | 8.3 (3) | 6.7 (1) | |

| Other | 5.6 (2) | 6.7 (1) | |

| Income (US $) | 0.14 | ||

| <15,000 | 58 (21) | 53(8) | |

| 15,000–24,999 | 19 (7) | 47 (7) | |

| 25,000–49,999 | 11 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| >50,000 | 11 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Insurance | 0.03 | ||

| Private | 26 (9) | 0 | |

| Medicare | 46 (16) | 33 (5) | |

| Medicaid | 23 (8) | 53 (8) | |

| Uninsured | 5.7 (2) | 13 (2) | |

| DM complications | 92 (33) | 100 (15) | 0.55 |

| Co-morbid illness | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 25 (9) | 33 (5) | 0.54 |

| Hypertension | 83 (30) | 93 (14) | 0.66 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 53 (19) | 47 (7) | 0.69 |

| Years with DM | 9.3 | 8.9 | 0.68 |

| Attendance | |||

| ≥7 sessions | 97 (35) | 40.0 (6) | <0.001 |

Missing 1 datapoint for age in group not enrolled in study and 1 datapoint for insurance status in group enrolled in study.

3.2. The three narratives in DEP

Study participants reported that all three narratives influenced their empowerment (e.g. self-efficacy, diabetes self-care behaviors and shared decision-making). We describe their responses below with illustrative quotes in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient perceptions of narrative's characteristics, mediators and outcomes.

| Narrative characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Engaging characters and stories | “I can see myself talking to the doctor that way…I enjoyed it a lot.” [Film] |

| “I was a little shy but…I opened up more by listening to someone else telling their part and then me telling mines.” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “We had fun with that and I wouldn't mind if we did have another week that occurred again because I enjoyed myself.” [Role play] | |

| Cultural embeddedness | “The foods you eat, vegetables, chicken. That is our culture. The food.” [Film] |

| “It's a lot of us that we don't [go to the doctor]. My mother will be 95 come August 28th and I went to see her in May and I could not get her to go to the doctor…that's our culture. We do that.” [Film] | |

| “They tell me what they experienced and how they take their [medication] … My teammates were telling me a lot of stuff like that I said I didn't know.” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “You learn more with a group than you do just being on a one-on-one basis because in a group everybody experiences something different or similar.” [Role play] | |

| Mediators of narrative's effect Transportation | “It reminded me of my younger days …it is like a flash from the past.” [Film] |

| “It had really brought me back.” [Film] | |

| “If I see it, then I know what's happening…So I would say that would motivate me, to see it, [more] than just talking about it. … it would be more on me if I seen it than just to hear it because if I see it, it's going to stick here” [Film] | |

| Identification | “When I was watching the video, I thought about myself and how when I go into the doctor's office, I don't always tell her exactly what's going on with me and how I feel.” [Film] |

| “I listened at the things that the other people went through… I had been in that same position that the other people were saying that they were in and then I'm just really thinking… and I'm saying, well maybe I should have did that.” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| Social proliferation | Discussion/diffusion |

| “When you hear the other patients talking about things that they didn't do or things that they did do, you can learn from that too… By you sitting there talking with the other one then you can learn.” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “Somebody might say…‘when I started doing this eating properly…my [sugars] went down’…Okay, I wonder if I did that will mine go down” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| Rehearsal/reinforcement of behaviors | |

| “When we role-played with Dr. Peek, it kind of broke down my shell. I didn't feel intimidated. She was teaching us step-by-step.” [Role Play] | |

| “We discuss a lot of things in class and we did a lot of little games…I kind of took heed of a lot of little things…and they kind of build me up.” [Personal Storytelling and Role play] | |

| Social support | |

| “Instead of me shunning and pushing away from [the education]…it's an inspiration because you hear what others go through, and we get a chance to share what we're going through” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “We were all friends. We would tell about different experiences and how some of them had really stuck to what they were supposed to do and lost weight. And you know that gave me the incentive… I look forward to every three-month [follow-up meeting] because you be running back to your friends.” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “It makes me feel good because I can let some of the things out that I didn't [even] know about myself …” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| Narrative outcomes/responses Attitudes/beliefs | “It makes you feel stronger because by you looking at that video and you listen at the doctors talking and then you looking at the patient … it makes me make better decisions for myself.” [Film] |

| “When I opened up, oh man, I felt like a brick was removed from off of my head because I was able to share what I was feeling…. They didn't interrupt me or nothing. They just sat there and listened and then when I sat down they gave me their opinions and how they felt about this and how they felt about that and that made me feel good.” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “I like the excitement on people's faces when they hear, ‘oh you have overcome that…’it just encourages me.” [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “When we did the role-playing, Dr. Peek told me I was a little bit too aggressive…if I talk to my doctor like that I don't think I would get anywhere with her. I don't want to be mad and mean and coming down on her like that but I will talk to her now. I don't want to be antagonistic.” [Role Play] | |

| Knowledge/skills | “It changed how I interact with the doctor… by me seeing the video, I did have the presence of mind to at least ask, ‘ What is this [medication] for? How often should I take it?”’ [Film] |

| “Some of the things that another person went through … you're going through the same thing and you listen to what they say and it gives you an option to‘either/or.’…So, you can say, ‘Okay, this is what I learned from what you had said and I feel great about it and myself.”’ [Personal Storytelling] | |

| “They kind of built me up… we'd be like we're at a doctor's session… and then she would say things that she know is not right either, but then she wants to know are we going to catch on to it and just let it go or will we just speak up?…sometimes you don't be wanting to question your doctor and it be kind of hard, especially if you really like them and stuff. So, she was just like building us up so that you've got to be able whether you like the doctor or not.” [Role play] |

3.2.1. The film

Almost all participants identified with the characters and events in the film. Everyone found the characters likeable and the story believable. The experience of watching the film, of seeing stories played out, seemed important to making participants feel that these situations had “actually” happened. Most participants felt the film culturally resonated with them.

Participants noted that watching the film prompted emotions and reflections on their own experiences. The film reportedly motivated participants and inspired them to work toward the relationships modeled. In some cases, the film provided a sense of social support.

3.2.2. Personal storytelling

Most participants liked sharing their personal stories. Several reported feeling initially unwilling to share, but becoming more expressive throughout the DEP. Participants felt that sharing and hearing personal stories enabled learning in an experiential way; as one participant said, “You can put yourself in that position.” In sharing stories, practical knowledge was transferred, and common issues were worked through collectively. Some participants reported that hearing from each other was more helpful than learning from the teachers.

Participants reported that storytelling promoted social support, decreased participants' sense of isolation, and relieved stress. Participants also noted that it boosted their self-confidence and motivated behavior change. Additionally, the desire to engage in personal storytelling reflected a sense of personal responsibility to help each other.

3.2.3. Role-play

Similar to personal storytelling, there was heterogeneity among participants' reported initial response to role-playing (from shy reluctance to enthusiastic participation), although the majority were receptive. Over time, with experience and continued exposure, all group members were able to participate in the role-play exercises and reported finding them valuable.

Participants noted that the role-play enabled group learning and discussion, helping to transfer knowledge and aiding in retention of information. To participants, the role-play felt realistic and increased their skill and confidence at handling common situations. It provided an opportunity to practice skills and share feedback, thus promoting tangible behavior change.

3.3. Mediators of narrative

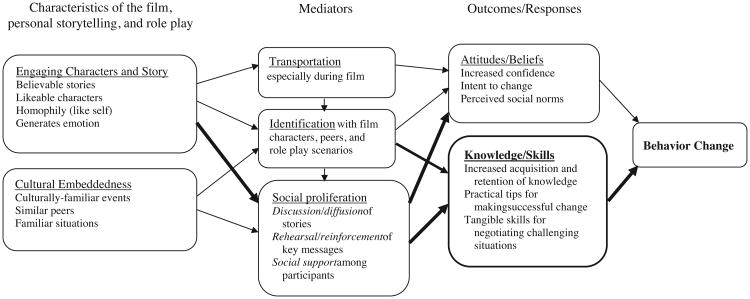

We found that all three mediators in Larkey and Hecht's model – transportation, identification, and social proliferation – were reflected in participants' responses, but that social proliferation was primarily emphasized (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Qualitative conceptual model of narrative's effect on African Americans with diabetes. Based on Larkey and Hecht's model of narrative as culture-centric health promotion [30], with our additions in bold.

3.3.1. Transportation

Participants reported being transported by the use of narrative in the DEP, particularly in regards to the film. Being transported into the stories portrayed in the film and by their classmates created an enjoyable experience and made the messages believable. This effect was particularly strong given the visual medium of the film; for our participants, seeing was believing.

3.3.2. Identification

Participants identified with the characters and events in the film, and also with each other's stories. This identification reportedly established trust and a sense of pragmatism, as self-management barriers and solutions were shared.

3.3.3. Social proliferation

While transportation and identification were present, participants overwhelmingly reported that the social proliferation of the narratives in the DEP – watching and discussing the film in a group, sharing personal stories with each other, and role-playing as a group – had an impact on their behavior change. Participants stated that social proliferation affected their attitudes and beliefs about behavior change by increasing their confidence and affecting their intent to change. They also perceived that social proliferation increased their relevant knowledge and taught them skills to undertake behavior change.

The social proliferation of these narratives was reportedly facilitated in three ways: discussion, rehearsal and social support. First, discussing these stories in a social setting generated teachable moments, which made the material more relevant and memorable for participants, facilitating knowledge acquisition and retention, and changing attitudes/beliefs about the stories' messages. Second, rehearsing the behaviors, through role-play or through discussion of stories in which behaviors are modeled, reportedly increased self-efficacy, disseminated practical strategies, and facilitated skills training in the self-management techniques introduced in the class. Third, social support was generated among participants while sharing and rehearsing these narratives (in often light hearted ways, e.g. pretending to be at a restaurant, with the teacher dressed as a chef). This social support reportedly changed participants' attitudes/beliefs, including their perceived social norms about health behaviors and patient/provider communication.

Of note, the themes from the individual interviews and focus groups were consistent. The two study participants who reviewed these results as part of a validity check corroborated the team's findings.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Our qualitative study explored whether patients who had completed the Diabetes Empowerment Program (DEP) perceived the narratives employed by program as contributing to the observed behavior changes (previously reported) [4]. Participants reported that all three narratives – the film, personal storytelling and role-play – promoted behavior change (e.g. foot care, glucose monitoring) and made them feel empowered (e.g. increased self-efficacy). The opportunity to process these narratives in a group setting, and the resulting social proliferation of narratives, was particularly important to participants. Discussing the stories, rehearsing them as a group, and building social support around them reportedly prompted new attitudes and beliefs, and generated new knowledge and skills about diabetes and shared decision-making. It is important to note that we define social support based on Barrera's model, which includes the domains of perceived support (subjective judgment that others will offer help), enacted support (supportive actions offered by others during times of need) and social integration (the extent to which a recipient is connected within a social network) [51]. We had designed the diabetes education classes with the goal of implementing all three of these aspects of social support [52].

4.2. Utilizing narratives to affect change

All three forms of narrative (i.e. film, storytelling and role-play) were reported to impact behavior change, and can be mapped onto a conceptual model of how they affected participants (Fig. 1, based on Larkey and Hecht's model with additions bolded). That is, the film, role-play, and storytelling all included characteristics that were engaging and culturally embedded, and mediated by transportation, identification, and social proliferation. All three narrative types were reported to impact both the attitudes/beliefs as well as the knowledge/skills of participants. Changes in attitudes/beliefs included a sense of being in control of diabetes, having a more positive health outlook, and increased confidence [4]. Increased knowledge/skills included better understanding of good nutrition, an enhanced ability to enact healthy lifestyle choices, and improved confidence in discussing treatment plans with their physicians. These changes were reported in the interviews and reflected in the prior work documenting increased measures of self-efficacy and self-care activities (e.g. healthy eating, glucose monitoring, and physical activity) [4].

The three forms of narratives map onto components of the model to different degrees. For example, the film was described as prompting transportation more than personal storytelling and role-play. Additionally, personal storytelling and role-play were well described as impacting both attitudes/beliefs and knowledge/ skills, while participants infrequently discussed how the film impacted their knowledge/skills.

4.3. Implications for theoretical models

Participants reported that our use of narrative impacted their behavior change through transportation, identification, and social proliferation. They described that these mediators impacted attitudes/beliefs and knowledge/skills, and ultimately promoted behavior change (Fig. 1). Our conceptual model of narrative's effect among these patients thus expands Larkey and Hecht's model in two key ways (bolded in Fig. 1).

First, Larkey and Hecht have only attitudes/beliefs listed as an outcome accompanying behavior change. However, our participants reported that the narratives transferred concrete knowledge and tangible skills. Specifically, narrative was reported to increase their acquisition and retention of new information (e.g. by making messages more memorable), facilitate sharing of practical strategies for making change (e.g. discussing how participants handled common management issues), and build tangible skills (e.g. through role-play of challenging situations). Second, our results indicate that the social proliferation of narrative may be even more influential than Larkey and Hecht propose. While participants corroborated Larkey and Hecht's description of how social proliferation can affect behavior change, they also reported that social proliferation impacted their attitudes/beliefs, by increasing their confidence and intent to change and affecting their perceived social norms. Thus, in our model, we interpret social proliferation as potentially linked to the outcomes promoted by narrative.

4.4. Conclusions

There has been a call for interventions to facilitate an increased “consciousness and articulation” of personal experience and perspectives, like our patients described, to facilitate participants' understanding of how behavior change may work in their everyday life [52]. Our study suggests that narrative shows promise as a tool to promote behavior change and empowerment among African-Americans with diabetes. Most existing models of narrative's effect focus on the individual level of processing, citing mediators such as transportation and identification. However, for some patient populations, including urban African-Americans with diabetes, we should consider the social context in which that processing occurs. The social proliferation of narrative – the discussion of stories, rehearsal of their messages, and resulting social support – was perceived to be particularly influential in our patient population and may be similarly important to other communities.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a qualitative study of urban African-Americans with diabetes, the majority of whom were women. It is possible that narrative is more influential in women; prior work on storytelling in African-American populations has also focused on women [52–54]. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to other populations. However, existing literature suggests that our findings may be relevant to other communities with strong traditions of storytelling. Second, our intervention used three narratives (film, personal storytelling, and role-play) simultaneously; to isolate the effects of any one, future empirical or quantitative studies could compare interventions delivering the same content via different narrative formats.

Our study also has several strengths. Using three narratives, and asking about them with open-ended questions, allowed participants to comment on each to the degree they felt was important. Our study is one of the first to use narrative in African-American adults with diabetes, a population with significant disparities in healthcare and outcomes.

5. Practice implications

Interventions aiming to improve diabetes self-management among African-American patients may find narratives, such as films, role-play, and storytelling, to be effective tools for behavior change. In general, health behavior change interventions utilizing narrative may be more effective if they include time to discuss and rehearse the stories presented, and foster an environment conducive to social support among participants. This emphasis on socially processing stories may be particularly important for promoting behavior change in minority communities, where information is often distributed through personal sources and strong traditions of storytelling are present. It may be particularly relevant for patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes, where the use of narrative may encourage active problem-solving of common issues in self-care and help facilitate shared decision-making between patients and healthcare providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Wanda Purdy-Johnson and Yue Gao for their assistance preparing the data.

Funding: This research is supported by the Merck Company Foundation and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) through an R18 (DK083946-01A1), the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK20595), and the Diabetes Research and Training Center (DRTC) (P60 DK20595).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest with this work.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [accessed April 17, 2013];National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States. 2011 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf.

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2020—diabetes. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [accessed April 17, 2013]. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/over-view.aspx?topicid=8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: a systematic review of healthcare interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64:101S–56S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peek ME, Harmon SA, Roberson TS, Hui Tang MS, Chin MH. Culturally tailoring patient education and communication skills training to empower African-Americans with diabetes. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2:296–308. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0125-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parchman ML, Zeber JE, Palmer RF. Participatory decision-making, patient activation, medication adherence, and intermediate clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a STARNet study. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:410–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivarius NF, Beck-Nielsen H, Anreasen AH, Horder M, Pedersen PA. Randomized controlled trial of structured personal care of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Brit Med J. 2001;323:946–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7319.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, Haas LB, Hosey GM, Jensen B, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S89–96. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazmararian JA, Ziemer DC, Barnes C. Perception of barriers to self-care management among diabetic patients. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:778–88. doi: 10.1177/0145721709338527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [accessed April 17, 2013];Diabetes disparities among racial and ethnic minorities: fact sheet. 2011 Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/fact-sheets/diabetes/index.html.

- 12.Murphy ST, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Narrative versus nonnarrative: the role of identification, transportation, and emotion in reducing health disparities. J Commun. 2013;63:116–37. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, Slater MD, Wise ME, Storey D, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:221–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epston D, White M. Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: Norton and Company; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams L, Labonte R, O'Brien M. Empowering social action through narratives of identity and culture. Health Promot Int. 2003;18:33–40. doi: 10.1093/heapro/18.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rappaport J. Empowerment meets narative: listening to stories and creating settings. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:795–807. doi: 10.1007/BF02506992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houston TK, Allison JJ, Sussman M, Horn W, Holt CL, Trobaugh J, et al. Culturally appropriate storytelling to improve blood pressure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinyard LJ, Kreuter MW. Using narrative communication as a tool for health behavior change: a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34:777–92. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, Kalesan B, Rath S, Richert M, et al. Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African-American women. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:S6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toussaint DW, Villagrana M, Mora-Torres H, de Leon M, Haughey MH. Personal stories: voices of Latino youth health advocates in a diabetes prevention initiative. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5:313–6. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkin HA, Ball-Rokeach SJ. Reaching at risk groups: the importance of health storytelling in Los Angeles Latino media. Journalism. 2006;7:299–320. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markus SF. Photovoice for healthy relationships: community-based participatory HIV prevention in a rural American Indian community. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2012;19:102–23. doi: 10.5820/aian.1901.2012.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers KR, Green MJ. Storytelling: a novel intervention for hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:129–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green MC, Clark JL. Transportation into narrative worlds: implications for entertainment media influences on tobacco use. Addiction. 2013;108:477–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreuter MW, Buskirk TD, Holmes K, Clark EM, Robinson L, Si X, et al. What makes cancer survivor stories work? An empirical study among African-American women. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larkey LK, Gonzalez J. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer prevention and early detection among Latinos. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glik D, Nowak G, Valente T, Sapsis K, Martin C. Youth performing arts entertainment-education for HIV/AIDS prevention and health promotion: practice and research. J Health Commun. 2002;7:39–57. doi: 10.1080/10810730252801183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ockene IS, Tellez TL, Rosal MC, Reed GW, Mordes J, Merriman PA, et al. Outcomes of a Latino Community-based intervention for the prevention of diabetes: the Lawrence Latino Diabetes Prevention Project. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:336–42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millan-Ferro A, Caballero AE. Cultural approaches to diabetes self-management programs for the Latino community. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2007;7:391–7. doi: 10.1007/s11892-007-0064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peek ME, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Odoms-Young A, Wilson SC, Chin MH. How is shared decision-making defined among African-Americans with diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:450–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raffel K, Goddu AP, Peek ME. “I Kept Coming for the Love:” enhancing the retention of Urban African Americans in Diabetes Education. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40:351–60. doi: 10.1177/0145721714522861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. New York, NY: Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slater MD, Rouner D. Entertainment–education and elaboration likelihood: understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun Theory. 2002;12:173–91. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larkey LK, Hecht M. A model of effects of narrative as culture-centric health promotion. J Health Commun. 2010;15:114–35. doi: 10.1080/10810730903528017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, Casey AA, Goddu AP, Keesecker NM, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:992–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green MC, Brock TC. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:701–2. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moyer-Gusé E. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment-education messages. Commun Theory. 2008;18:407–25. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peek ME, Wilkes AE, Roberson TS, Goddu AP, Nocon RS, Tang H, et al. Early lessons from an initiative on Chicago's South Side to reduce disparities in diabetes care and outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:177–86. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Funnell MM, Anderson RM, Arnold MS, Barr PA, Donnelly M, Johnson PD, et al. Empowerment an idea whose time has come in diabetes education. Diabetes Educ. 1991;17:37–41. doi: 10.1177/014572179101700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peek ME, Wilson SC, Gorawara-Bhat R, Quinn MT, Odoms-Young A, Chin MH. Barriers and facilitators to shared Decision-Making among African Americans with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1135–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson SC, Chin MH. Race and shared decision-making. Perspectives of African-American patients with diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson SC, Chin MH. Racism in healthcare: its relationship to shared decision-making and health disparities: a response to Bradby. Soc Sci Med. 2010;7:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peek ME, Tang H, Cargill A, Chin MH. Are there radical differences in patients' shared decision-making preferences and behaviors among patients with diabetes? Med Decis Making. 2011;31:422–31. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10384739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyd SA, Wilmoth MC. An innovative community-based intervention for African-American women with Breast Cancer. Health Soc Sci Work. 2006;31:77–80. doi: 10.1093/hsw/31.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erwin DO. Development of an African-American role model intervention to increase breast self-examination and mammography. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7:311–9. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.QSR International. Dorcester, VIC: QSR International; 2012. NVivo 10. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. Br Med J. 2000;320:114–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analysing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1993. pp. 173–94. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bandura A. Self-efficacy The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman & Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peek ME, Ferguson MJ, Robertson TS, Chin MH. Putting theory into practice: a case study of diabetes-related behaviorial change interventions on Chicago's South Side. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(2 Suppl):40S–50S. doi: 10.1177/1524839914532292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Banks-Wallace J. Womanist ways of knowing: theoretical considerations for research with African-American women. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2000;22:33–45. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams-Brown S, Baldwin DM, Bakos A. Storytelling as a method to teach African-American women breast health information. J Cancer Educ. 2002;17:227–30. doi: 10.1080/08858190209528843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]