Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the behavioral effects of a theory-driven, mobile phone–based intervention that combines automated text messaging and remote nursing, using an automated, interactive text messaging system.

Methods

This was a mixed methods observational cohort study. Study participants were members of the University of Chicago Health Plan (UCHP) who largely reside in a working-class, urban African American community. Surveys were conducted at baseline, 3 months (mid-intervention), and 6 months (postintervention) to test the hypothesis that the intervention would be associated with improvements in self-efficacy, social support, health beliefs, and self-care. In addition, in-depth individual interviews were conducted with 14 participants and then analyzed using the constant comparative method to identify new behavioral constructs affected by the intervention.

Results

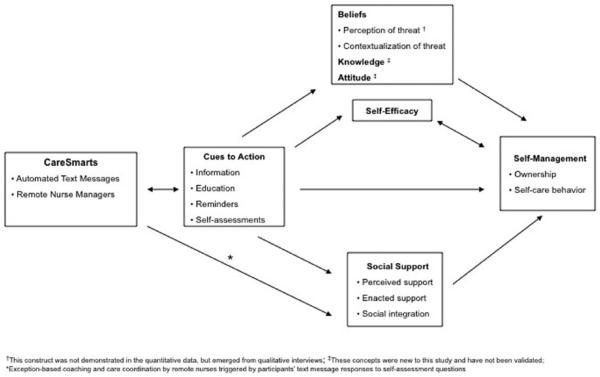

The intervention was associated with improvements in 5 of 6 domains of self-care (medication taking, glucose monitoring, foot care, exercise, and healthy eating) and improvements in 1 or more measures of self-efficacy, social support, and health beliefs (perceived control). Qualitatively, participants reported that knowledge, attitudes, and ownership were also affected by the program. Together these findings were used to construct a new behavioral model.

Conclusions

This study’s findings challenge the prevailing assumption that mobile phones largely affect behavior change through reminders and support the idea that behaviorally driven mobile health interventions can address multiple behavioral pathways associated with sustained behavior change.

Introduction

Despite considerable progress, self-management remains an important barrier to optimal glycemic control in many individuals with diabetes.1,2 While conventional behavioral support interventions can be effective,3-5 they generally do not result in sustained behavior change and require significant resources and patient commitment, limiting accessibility to large populations. Given the growing burden of diabetes worldwide and persistence of preventable morbidity and mortality, readily scalable yet effective behavior change strategies are urgently needed.

Recently, mobile phone technologies, and in particular automated text messaging, have emerged as a promising platform for behavior change,6,7 giving rise to the field of mobile health or mHealth. In addition to being widely available and low cost,8,9 text messages are instantaneously delivered at any time, place, or setting and therefore have the capacity to interact with the individual in real time, with much greater frequency and contextual relevance than conventional behavior change mediums or even computer-based ones.7 Moreover, with 2-way communication, text messaging interventions have the potential to be “just in time”—for example, adapt to an individual’s frequently changing health status and environmental contexts—and therefore be more individually tailored.10

Although improved behaviors and clinical outcomes in diabetes have been demonstrated in a number of mobile health studies,11 including a recent randomized study,12 little is known about how mobile phone–based diabetes interventions actually drive behavior change. A recent review found that few mobile phone disease management interventions were theoretically guided, and of those with a theoretical basis, few formally evaluated any of the behavioral components hypothesized to be affected by the intervention.13 This is not only of academic interest. Studies show that theory-driven behavioral messaging interventions are more effective than those that are not theory based.6,14 Moreover, behavioral theory can inform evaluation and identify which component(s) of an intervention are most effective15,16—evidence that may aid in program design.

The purpose of the current study was to (1) assess the behavioral effects of CareSmarts, a theory-driven diabetes intervention that combines automated text messaging with remote nurse support, and (2) validate the underlying behavioral model for how mobile phone–based interventions affect self-management. The model, which was developed in a prior study,17 hypothesizes that self-management improves as a direct result of reminders (eg, cuing) and informative texts but also indirectly through self-efficacy, social support, and health beliefs. Mixed methods were used to achieve study aims, utilizing survey instruments and qualitative research methods, and hypothesized that the intervention would be associated with pre-post improvements in self-care activities, self-efficacy, social support, and health beliefs.

Methods

Research Design

This is a mixed methods observational cohort study. Qualitative methods (in-depth interviews) and quantitative methods (survey data analyses) were used to evaluate a 6-month mobile phone–based intervention that combines automated text messaging and remote nursing using an automated, interactive text messaging system.

Study Sample and Setting

The study took place at the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM), an academic medical center on Chicago’s South Side. Study participants were all members of University of Chicago Health Plan (UCHP), a health plan serving employees of the University of Chicago and UCM and their dependents, who largely reside in the working-class, urban African American community surrounding the institution. Study participants were adults ages 19 and older with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who received primary care or diabetes specialty care at UCM. Individuals without access to a personal mobile phone were excluded.

Recruitment

After study approval from the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board, consent was obtained from individual physicians to approach their patients for study recruitment. Patients were recruited between May and August 2012 for a 6-month intervention. All eligible adults received a culturally tailored mailing and up to 2 recruitment calls; individuals with poorly controlled diabetes (A1C ≥8%) were prioritized for recruitment and received up to 10 phone calls. A $25 cash incentive was provided upon completion.

Data Collection

Survey data were collected by telephone at baseline, 3-month follow-up (mid-intervention), and 6-month follow-up (end of intervention). In addition, a subset of participants was invited to participate in individual, in-depth interviews with a member of the research team (PH) for approximately 1 hour. A range of participants of varying ages, engagement levels, and satisfaction with the program were recruited until theme saturation. Topic guides were used to provide structure for the interview; these included open-ended questions with follow-up probes. Each interview was audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Intervention

CareSmarts is a theoretically guided, mobile phone–based intervention for diabetes behavioral support. It has been described previously and has been shown to improve diabetes control and reduce health care costs among program participants.18,19 Briefly, the central component of CareSmarts is an automated, interactive text messaging system. Through the web-based software, patients receive educational messages and reminders about medications, glucose monitoring, exercise, nutrition, and foot care (eg, “Time to check your blood sugar”) and text back responses to questions (eg, “On how many of the past 7 days did you take all of your diabetes medications?”). Patients’ individual text message programming is tailored during the enrollment process based on their medication and blood glucose monitoring regimens, baseline self-management behaviors, and message timing preferences. It is then “dynamically tailored” every 2 weeks based on participants’ preferences and responses to self-assessments. For example, individuals who report low medication adherence or request more frequent reminders will receive more medication reminders than those with high adherence preferring fewer reminders. The system draws from a message bank of over 800 messages that reflect the underlying behavioral model, including education messages (“Did you know that experts recommend moderate physical activity for at least 30 minutes 4 times per week?”), encouragement (“We know managing diabetes can be hard, but you can do it!”), cues (“Time to take your diabetes medication”), assessments (“On how many of the last 7 days did you take all of your diabetes medications?”), and feedback (“7 for 7, perfect!”).

Participants are enrolled in CareSmarts over the phone by trained nurses, who then periodically contact them if their responses to self-assessments are outside of predefined parameters. For example, if a participant texts yes to “Do you need refills on any of your medications,” he or she will receive a phone call from a nurse to assist with refilling medications. Similarly, a participant who reports low medication adherence will be called and provided tailored education and encouragement. The enrollment process and subsequent outreach calls are designed to build and establish a personal rapport with participants and reinforce the human element behind the CareSmarts program.

Measures

Diabetes Self-care Measures

The Toobert et al Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure (SDSCA) assesses 5 areas of self-care practice on a 1-week scale (with response options ranging from 0 to 7 days): healthy eating, high fruits/vegetables and low fat intake, exercise, blood sugar testing, and foot care. It is a brief, valid, and reliable measure of self-reported self-management that correlates with other measures of dietary patterns (eg, 3- and 4-day food records) and physical activity (eg, enrollment in an exercise class).20

Medication Adherence

Two self-report measures of medication adherence were used: (1) a 1-item question from the SDSCA of weekly medication adherence (response options 0-7 days) and (2) the Morisky 4-Item Self-report Measure of Medication-Taking Behavior (composite scale 0-4).21,22 Although both measures correlate with objective measures of medication adherence (eg, claims data), rates of discordance are high,23 and so both measures were utilized.

Diabetes Self-efficacy

Diabetes self-efficacy was measured using the 8-item Diabetes Self-efficacy Scale (DES) (with 4-point Likert-type responses from 1 = not at all sure to 4 = very sure) that assesses confidence and ability to manage one’s diabetes. The DES has been found to correlate with self-management across a range of race/ethnicity and literacy levels.24,25

Health Beliefs

Subscales of the Risk-Perception Survey for Diabetes (RPS-DM)26,27 and Diabetes-Related Health Problems (DRHP)28 were chosen to match behavioral constructs observed in our prior qualitative study.17 The RPS-DM was designed to measure comparative risk perceptions and has been shown to improve in individuals who receive targeted education related to complications of diabetes.29 From RPS-DM, a 5-item measure of risk knowledge (with 3-point responses “increases the risk of getting diabetes complications,” “has no effect on the risk,” and “decrease the risk of getting diabetes complications”) and a 4-item measure of perceived personal control (with 4-point Likert-type responses from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree) were measured. From DRHP, 2 measures of participants’ perceptions of the likelihood of specific long-term complications, which have been found to correlate with other validated measures of health beliefs,28 were assessed: (1) a 4-item measure of complications to someone else with diabetes and (2) 4-item measure of complications to themselves (each with 5-point responses: not at all likely, not too likely, fifty-fifty, pretty likely, and very likely).

Social Support

Two 1-item measures of social support by Tang et al30 associated with diabetes-specific quality of life and self-management behaviors measured (1) the amount of social support received (5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = no support to 5 = a great deal of support) and (2) satisfaction with social support (5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = not at all satisfied to 5 = extremely satisfied). In addition, 4 additional 1-item instruments similar to the Tang et al measures were developed to capture additional elements of social support observed in the pilot study: (1) amount of daily social support received (5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = no support to 5 = a great deal of support), (2) satisfaction with daily social support (5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = not at all satisfied to 5 = extremely satisfied), (3) satisfaction with monitoring (5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = not at all satisfied to 5 = extremely satisfied), and (4) satisfaction with encouragement and feedback (5-point Likert-type scale from 1 = not at all satisfied to 5 = extremely satisfied).

Topic Guides

Topic guides were created for the in-depth interviews with the goal of exploring participants’ experiences with the CareSmarts program including both the text messaging and remote nursing components and perceptions of the impact of the program on diabetes self-management. The guide consisted of a list of neutrally worded, open-ended questions and follow-up probes. Queries began with, “How was the program different from what you expected or wanted going into it?” and followed with probes such as “Can you describe in more detail what you mean by that?” Later in the interview guide, questions were specifically asked about changes to self-efficacy, social support, and health beliefs (eg, “Some patients also told us that the program changed the way they thought about their diabetes while others said it had no effect. Thinking back, have your attitudes or beliefs about diabetes changed in any way and if so, how?”) and suggestions for improving the intervention (eg, “How could we make the CareSmarts program better?”).

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses of participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were conducted with the use of means and standard deviations. Patient survey data were collected at baseline, 3 months, and program completion at 6 months to assess diabetes self-care activities, self-efficacy, health beliefs, and social support. Pairwise t tests were used to access changes from baseline to each follow-up time point. A generalized linear mixed effect model was also used to evaluate the intervention effect on each outcome measure over time. The model included Poisson mixed regression for the self-care activities and social support measures and Gaussian mixed regression model for self-efficacy, health beliefs, and 4-item Morisky scale. All analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 12.1. The significance level was P < .05.

Individual interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, and imported into Atlas.ti 6.1 software. All deidentified, anonymous transcripts were coded by a team of 5 investigators with experience in medicine, diabetes education, and public health. An initial codebook was developed based on themes that emerged in the previous pilot study including cuing, health beliefs, social support, and self-efficacy. Five coders all independently coded the first transcript and then met as a team to discuss the transcript and codes and create uniform coding guidelines. Subsequently, each transcript was independently coded by 2 randomly assigned reviewers, who then met to resolve coding discordance. Outstanding issues were resolved by the group. New concepts and themes were discussed in an iterative fashion until a final codebook was created and all themes had emerged.

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Of the 372 adult members of UCHP with diabetes eligible for this study, 74 were successfully enrolled and 67 completed the entire 6-month intervention and follow-up (Table 1). Reasons for discontinuing included not finding the program helpful (n = 3), loss to follow-up (n = 3), and termination of health plan membership (n = 1). Participants were all under age 70, and the average age was 54 years. Over half identified themselves as African American (54%), and the median individual had at least some college or an associate’s degree. About one-third of participants had well-controlled diabetes A1C ≤7%, one-third moderately controlled diabetes A1C 7% to 8%, and one-third poorly controlled diabetes A1C ≥8%.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Treatment Group (N = 74)

| Characteristic | Na (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean [SD] | 54.1 [9.3] | |

| Gender, N (%) | Female | 40 (54.0) |

| Race, N (%) | African American | 39 (54.2) |

| White | 24 (33.3) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (1.4) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 6 (8.3) | |

| Other | 2 (2.8) | |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | Non-Hispanic | 65 (91.5) |

| Hispanic | 6 (8.5) | |

| Job status, N (%) | Employed | 60 (84.5) |

| Not working/retired | 11 (15.4) | |

| Marital status, N (%) | Married | 45 (61.6) |

| Single | 18 (24.7) | |

| Divorced or separated | 7 (9.6) | |

| Widowed | 3 (4.1) | |

| Education, N (%) | No high school | 0 (0) |

| High school graduate | 9 (12.7) | |

| Some college or associate’s | 31 (43.7) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 21 (29.6) | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 10 (14.1) | |

| Diabetes diagnosis, N (%) | Type 2 | 71 (95.9) |

| Type 1 | 3 (4.1) | |

| Years since diagnosis, mean [SD] | 8.1 [7.2] | |

| Baseline A1C, mean [SD] | 7.9% [2.1%] | |

| Diabetes medication regimen, N (%) | Diet alone | 7 (9.5) |

| Oral agents only | 36 (48.7) | |

| Any insulin | 31 (41.9) | |

| Self-glucose monitoring regimen, N (%) | As needed | 5 (6.8) |

| A few times per week | 4 (5.4) | |

| Once daily | 31 (41.9) | |

| > once daily | 34 (45.9) |

All values are number (N) and percentage (%), unless specified.

Behavioral Measures

At 3 months, the number of days in the past week participants performed a self-foot exam (P = .01) and exercised for at least 30 minutes (P = .04) improved compared to baseline (Table 2). At 6 months, in addition to exercise and foot care, 1 of the 2 measures of healthy eating (P = .02) and 1 of the 2 measures of self-glucose monitoring improved (P = .01). At both 3 months (P < .01) and 6 months (P = .02), the 4-item Morisky Medication Adherence score improved compared to baseline; however, no change in weekly medication adherence was observed. In the random effects model, improvements were observed in 1 or more measures of blood glucose monitoring, foot care, exercise, healthy eating, and medication adherence. No changes in consumption of recommended servings of fruits and vegetables and low amounts of fat were observed.

Table 2.

Self-care Activity Measures: Comparison of Baseline, 3-Month, and 6-Month Scores

| Variable | Baseline | 3 Month | 6 Month | 0 versus 3 Month |

0 versus 6 Month |

Random Effects |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| N | Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean | P Valuea | P Valuea | P Valueb | ||

| Self-care activities | SMBG at least once per day | 74 | 4.5 | 64 | 5.3 | 65 | 5.1 | .06 | .01 | .04 |

| (all measures on a 7-day scale) |

SMBG as recommended by provider | 74 | 4.4 | 64 | 5.2 | 65 | 5.2 | .40 | .12 | .12 |

| Foot examination | 74 | 2.2 | 64 | 2.6 | 65 | 2.7 | .01 | .16 | .12 | |

| Shoe inspection | 74 | 2.8 | 64 | 3.0 | 65 | 2.8 | .91 | .02 | <.01 | |

| Exercise session | 74 | 2.8 | 64 | 3.4 | 65 | 3.4 | .38 | .78 | .81 | |

| Physical activity | 74 | 5.9 | 64 | 6.0 | 62 | 6.3 | .04 | <.05 | .02 | |

| Healthy eating in the past week | 74 | 4.5 | 64 | 5.0 | 65 | 5.3 | .10 | .10 | .13 | |

| Healthy eating in the past month | 74 | 4.0 | 64 | 4.3 | 65 | 4.6 | .12 | .02 | .03 | |

| Intake of fruits and vegetables | 74 | 4.9 | 64 | 6.0 | 65 | 5.5 | .41 | .59 | .52 | |

| Recommended intake of fats | 74 | 2.2 | 64 | 2.2 | 65 | 3.1 | .24 | .21 | .11 | |

| Medication adherence | Adherence in the past week (0-7) | 74 | 4.1 | 64 | 4.4 | 65 | 4.4 | .51 | .42 | .42 |

| Morisky 4-item (0-4) | 74 | 2.9 | 64 | 3.3 | 62 | 3.4 | <.01 | .02 | <.01 | |

Abbreviation: SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

The P values are computed from pairwise t tests.

The P values are from generalized linear mixed effect models.

Self-efficacy improved at 3 months compared to baseline (P = .01) and remained improved at 6 months (P = .01) (Table 3). The amount of social support received overall and received daily improved at 3 months and 6 months, while satisfaction with overall and daily social support improved only at 6 months. Satisfaction with feedback also improved at 6 months (P = .02). None of the health belief measures significantly changed at 3 months; at 6 months participants perceived an increased risk of long-term diabetic complications in others (P = .2), but not themselves (P = .54), and an increase in perceived personal control (P = .04). In the random effects model, only self-efficacy, amount of daily social support, risk of long-term complications in others, and perceived control changed over time.

Table 3.

Self-efficacy, Social Support, and Health Belief Measures: Comparison of Baseline, 3-Month, and 6-Month Scores

| Variable | Possible Range | Baseline | 3 Month | 6 Month | 0 versus 3 Month |

0 versus 6 Month |

Random Effects |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| N | Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean | P Valuea | P Valuea | P Valueb | |||

| Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy | 8-32 | 71 | 27.3 | 64 | 28.5 | 60 | 28.1 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Social support | Amount of support received |

1-5 | 71 | 3.8 | 64 | 4.2 | 64 | 4.4 | .02 | .00 | .12 |

| Satisfaction with support | 1-5 | 71 | 4.1 | 64 | 4.4 | 64 | 4.5 | .14 | .01 | .36 | |

| Amount of daily support | 1-5 | 71 | 3.4 | 64 | 3.9 | 64 | 4.2 | .01 | .00 | .02 | |

| Satisfaction with daily support |

1-5 | 71 | 4.1 | 64 | 4.4 | 64 | 4.5 | .11 | .02 | .28 | |

| Satisfaction with monitoring |

1-5 | 71 | 4.1 | 64 | 4.2 | 64 | 4.4 | .46 | .05 | .39 | |

| Satisfaction with feedback |

1-5 | 71 | 4.2 | 64 | 4.3 | 64 | 4.5 | .56 | .02 | .38 | |

| Health beliefs | Long-term complications in others |

5-20 | 71 | 15.1 | 64 | 15.2 | 64 | 16.0 | .92 | .02 | .03 |

| Long-term complications in self |

5-20 | 71 | 10.6 | 64 | 11.2 | 63 | 10.9 | .28 | .94 | .54 | |

| Risk knowledge | 5-15 | 71 | 10.9 | 64 | 11.1 | 63 | 11.0 | .12 | .22 | .54 | |

| Perceived personal control |

4-16 | 71 | 9.6 | 64 | 9.9 | 64 | 10.0 | .23 | .04 | .04 | |

The P values are computed from pairwise t tests.

The P values are from generalized linear mixed effect models.

In-depth Interviews

A number of themes emerged concerning how the program affected individuals’ self-care activities, self-efficacy, social support, and health beliefs, many of which were described in the prior pilot study17 and observed in the survey measures described previously (Table 4). In addition, themes emerged regarding threat perception, a construct of health beliefs seen in our prior study but not demonstrated quantitatively here, and new constructs including participants’ attitudes, knowledge, and ownership of diabetes, which are discussed in the following.

Table 4.

Selected Participant Commentary on the Behavioral Effects of the CareSmarts Intervention

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Cues to action | [The text messages] were definitely helpful in keeping me on track. Helpful in reminding me about testing and medication. Umm, and umm giving me tips, things like you know don’t test just in the morning, test at other times during the day, I forgot some of the other tips. Oh, you don’t have to stick it in the middle of your finger, you can stick it in the side of your finger so there were some certainly useful facts and stuff aside from just the reminding. I think it is because sometimes you avoid thinking about maybe being diabetic because then you have to make choices and maybe, you want to have a piece of pie or maybe you don’t want to exercise. So, you don’t. You eat the pie and maybe your sugar doesn’t show it, and you eat pie tomorrow, too and you don’t exercise because your sugar doesn’t show it. But, the program put it in front of my mind, so I did make better choices, and especially with the exercising and a little bit better eating. I liked the reminders, umm, my days sometimes can get kind of hectic so just having that reminder, especially if like I’m doing this job and another job, I might forget to do some things so just having a reminder, hey you might want to take some meds, it works. Because sometimes I’m again not feeling well and like why don’t I feel good? Oh, you didn’t take your medicine today so when the texts come across I might you know remember that so. It was just that it was a reminder of, “Don’t forget you’re diabetic, today.” You know that’s why it worked for me. |

| Self-efficacy | You can be confident in taking your readings and taking your medications but are you confident that you are doing it the right way. You might be doing it but are you doing it the right way so these text messages sort of lead you into doing it the right way; are you checking it the right number of times. I am checking my blood sugar but I was not checking it the right number of times a day so that doesn’t mean that I wasn’t doing something. I am taking my medicine but am I taking all of it and the number of times it is prescribed. So that is what it helps you do because you can be doing it but you are not doing it the right way which is important. But, the program put it in front of my mind, so I did make better choices, and especially with the exercising and a little bit better eating. And then, I feel better. And so, I realize that if I make the right choices, I will get a better result overall. So, I do feel more confident in that because you start to feel like no matter what I do, I’m falling apart like left and right. What is the point? But, I do. I feel a lot better with the exercise, and even though my sugar has always been good, I can see that I can make improvements. It’s not just about that sugar number. It’s about are you taking care of your body because it is all connected. |

| Beliefs | Interviewer: Do you think your attitudes or beliefs about your diabetes have changed in any way? Interviewee: I would say so, yes. I think I guess you are sort of in denial that it is going to go away and the doctor made a mistake, but eventually you will say this is it you have to deal with it, you’ve got it so yeah I think it has. I would say I’m more concerned about it [after completing the program]. Umm, more concerned about keeping it under control, a little bit umm more aware of what the consequences are and probably a higher awareness that I’m not superman and not immune to them. That unless I do control it, there are going to be consequences. So yeah I think my outlook has gotten more realistic and more pragmatic. |

| Knowledge | Interviewer: What types of messages did you like reading more than others? Interviewee: Sometimes, they’ll ask you questions like, “Do you know that you’re supposed to have five fruits and vegetables?” I was like, “Huh, really?” Or, it would say, “Do you know that a normal blood sugar level is between this and this?” I’m thinking, “Well, I don’t know how I couldn’t know that,” but I didn’t. So, those kinds of informative things were good. The tip I remember is I usually eat fruits, a lot of fruit and according to the text messages stay away from the canned foods, I mean canned fruit. I didn’t know that. I used to love that stuff. It’s high in sugar. But like I said I’m more aware of my sugar intake than before. |

| Attitudes | I think I’m a lot more tuned into myself to the point that before it’s like, oh, I’m diabetic and I have to deal with this and this sucks and all of that and now I’m like, okay, I’m diabetic and I can’t have that and I have to watch this and I have to watch that and it’s okay, no problem. I’m not as hard on myself now as I was before. I used to be super hard on myself and now it’s let me know, okay, it’s just a condition, it’s you know, people call it a disease but it’s a condition. |

| Social support | Interviewer: So you described it as a “safety net.” Can you just sort of describe in a little more detail what you mean by that? Interviewee: It means that umm I don’t have to rely entirely on myself. In other words, umm without the messages I have to get up in the morning and say ah, test blood sugar, make sure you eat something and take the medication and it’s on me. Umm, my wife is not going to say did you take your blood sugar, the dog isn’t going to come up and yap at me because I didn’t test or something like that. It’s on me. Whereas here I’ve got something else, something external, something from the outside prompting me. It’s something that is not under my direct control that I can forget about or turn off or ignore, well yes I could certainly ignore it. But it’s something out there outside of my control which is going to prompt me. Well like I said the foot care was important and it is a reminder you know did you take you medicine. I have funny eating habits so just a reminder that you asked me did I take my medicine made me want to take it like I am supposed to take it, twice a day not once a day in the middle of the day. So it’s like I don’t want to say someone watching over you in a bad way with a negative connotation but with a positive like “are you doing what you are supposed to do” or “this is what you need to do to get better or stay better” so I liked it for that reason. It wasn’t my doctor saying it in a mean way it was a text message saying did you take your medicine today. I appreciated that. |

| Ownership | Interviewee: I think this is what this helps you to do so now when you get a text message did you check your blood sugar the number of times recommended by your physician and you can say yes, almost instead of no I didn’t. I literally did that one day. I didn’t even respond I am like I am not responding because she is going to call me so why respond so I just didn’t respond. It makes you take some responsibility for yourself and I didn’t want you to know I wasn’t doing that. So that is a good thing. Interviewer: Asking people to take responsibility? Interviewee: Yeah, or did you do it reminding you so it made me say to myself okay by the time they send me this question again I will have done better because we want to do better for ourselves whether we admit it or not. Because it did make me accountable for testing and taking medication and umm, as I say it made me feel guilty. It reminded me and said did you check. And you know it felt good to say yes, I did, my blood sugar was so and so. It was positive feedback for me in being able to respond positively to these questions and umm to me that’s valuable and I can see this sort of tailing off. Yes, it’s a habit now but oops well I forgot this morning I skipped it or didn’t do it or you know it goes downhill. I feel that I could maintain this much better if I had the umm text messages reminding me and keeping me accountable so I feel that it’s helped me and umm, will continue to help me and without it there would be a distinct possibility I would backslide. I wouldn’t say I would definitely or not but I know that it’s you know easy to do and ahh this would be a crutch or an aid to not backsliding. |

Threat Perception

Participants reported becoming less in denial of their diabetes as a result of the program (perceived susceptibility) and more awareness of the seriousness and consequences of their condition (perceived severity). This was sometimes attributed to the frequency of the messages they received (eg, weekly foot care reminders) and sometimes to the content of the messages (eg, education about the risk of harmful foot infections in diabetes).

I would say I’m more concerned about it [after completing the program]. Umm, more concerned about keeping it under control, a little bit umm more aware of what the consequences are and probably a higher awareness that I'm not superman and not immune to them. That unless I do control it, there are going to be consequences. So yeah I think my outlook has gotten more realistic and more pragmatic.

Attitudes About Diabetes

Participants described developing a more positive attitude about their diabetes and becoming more optimistic about their general health outlook.

It's helped my attitude about the condition and my attitude about me, you know, I used to have really, really poor self-esteem because of it thinking that, well, I can't do this and I can't do that. I can do anything I want to do as long as I just take care of myself and that's what this program helped me realize that, you know, it's about what I do for me and that's it. Don't worry about what anybody else has to say.

Knowledge

The text messages also helped increase participants’ knowledge about their diabetes and about self-care. Participants felt that at times the program helped them recall information they had received elsewhere and at other times provided them new information (eg, importance of foot care).

Another thing is something that came across as a message or whatever but I never used to stick my thumb and I'm going well I keep rotating between four fingers, what’s the matter with the thumb? Sure it works, it’s got blood just like everything else. So yeah, umm information like, I say it should be obvious to the casual observer that, you know, there is blood all over the place you don’t have to stick right in the center of the finger but it wasn’t to me. It was something that umm “oh yeah” and I think there are a lot of things that people don’t necessarily, that are out there and “everybody knows them” and stuff but they may not necessarily be aware of or it may not be something they have encountered.

Many participants requested additional information including interpreting blood sugar values, healthy recipes for diabetes, and community resources for physical activity.

Ownership of Diabetes

Participants stated that the program made them feel more “accountable” for their condition. They began to feel that they were responsible for their diabetes care and started setting goals for themselves outside of the prompts and reminders they received from the program.

Even after 6 months, I’ve been getting some messages and lot of them I would just dismiss and sometimes, they would sink in, especially. I would think about it. Okay, well, you should watch what you’re eating. But, I just realized when we talked the other day, it’s like, “Oh, how good are you?” “Oh, I’m really good. I do really good. I’m really good.” “So, how many days this week did you eat 5 servings of vegetables and fruits?” And, I’d be like, “None.” So, I’m thinking, “How good are you?” You think you’re good but then, you’re not. So, I’m not doing parts of what I should be doing because I think I’m so good at these other parts. So, it just reminded me that if it’s available and if I take it for how it works for me, when the texts come through, it should remind me 5 fruits and vegetables. So that’s kind of my goal this year is to do better about eating those 5 fruits and vegetables.

Behavioral Model

The model hypothesizes that CareSmarts improved self-management directly through cues to action and enacted support but also indirectly through knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, self-efficacy, and social support (Figure 1). Automated text messages provide participants with information, education, reminders, and self-assessments, while remote nursing provides information, education, and enacted support (eg, telephone-based coaching, assistance with refills). These cues to action affect contextualization of threat (eg, perceived benefits and perceived benefits of adopting a promoted behavior), perception of threat (eg, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity), knowledge of diabetes, and attitudes toward diabetes. Cues to action also help build self-efficacy and together with remote nursing increase participants’ sense of social support. Social support, self-efficacy, and knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in turn affect individuals’ self-care activities and their sense of ownership over their condition.

Figure 1.

Proposed behavioral model for CareSmarts intervention that combines automated text messaging and remote nurse support.

Discussion

This study explores the behavioral effects of a mobile phone diabetes self-management intervention that has previously been shown to improve diabetes control and reduce health care costs.20 Findings indicated that this theory-based intervention was associated with improvements in each of the major self-care domains—medication taking, self-monitoring of blood glucose, foot care, exercise, and nutrition—and improvements in self-efficacy, social support, and health beliefs as hypothesized in this behavioral model. These findings challenge the prevailing assumption that mobile phones largely affect behavior change through reminders (eg, cues to action) and support the idea that behaviorally driven mobile health interventions can address multiple behavioral pathways associated with sustained behavior change.

This study adds to a small but growing body of evidence demonstrating how mobile phone diabetes interventions drive behavior change. Although a number of studies have demonstrated improvements in self-management and glycemic outcomes,31 we are only aware of 1 other mobile phone diabetes intervention that attempts to explore the underlying behavioral effects of their intervention. In the Sweet Talk trial, a text messaging intervention in adolescents with type 1 diabetes based on social cognitive theory, investigators observed increased diabetes self-efficacy and social support in the treatment groups compared to control.32 Outside of diabetes applications, a number of effective smoking cessation and weight loss mobile phone interventions have been based on the transtheoretical model, social cognitive theory, and theory of planned behavior.13 However, few studies have evaluated whether the behavioral constructs implicated in their models are in fact affected by the intervention. Thus, this study fills an important gap in theory-driven mobile health interventions and the evidence base for how these promising interventions support behavior change and, ultimately, health outcomes.20

Because mobile phones are a platform, and not a solution itself, behavioral pathways that are affected depend critically on program design. In this study, participants reported that their interactions with remote nurses were important to their sense of increased social support. Although participants never met with their nurses face to face, they were all staff members in participants’ health plan, had expertise in diabetes, and provided education and assistance when needed—all of which helped build participants’ social connection with the program, which the text messages then reinforced and strengthened. Two-way interactivity in this program gave participants the opportunity to text back responses to self-assessments and receive immediate feedback (eg, “Great job!”), which helped build self-efficacy. Finally, the content of the text messages, which included not only tips on healthy eating but also encouragement messages, increased participants’ knowledge about diabetes and shaped their attitudes about their condition. Numerous studies show that social support,33,34 self-efficacy,35 health beliefs,36 attitudes,37 and knowledge38 are all important mediators of diabetes self-management—findings that underscore the importance of leveraging these behavioral pathways when designing behavior change interventions using mobile phones.

Importantly, these behavioral mediators were not equally relevant across all patients. For example, some participants found the knowledge they gained from informational texts more helpful for self-managing their diabetes than the reminders while others found reminders invaluable for keeping organized and reinforcing the seriousness of their condition. These individual-level differences may help explain why no measurable improvements were found in survey measures of threat perception despite reports of increased awareness of personal risk of complications and greater acceptance of diabetes among patients in individual interviews. Higher baseline knowledge and awareness of diabetes, as may be observed in individuals with higher socioeconomic status,39 may have made these mediators less salient to most participants, even though they were highly relevant to some. Because tailored interventions have greater efficacy than nontailored interventions,40 these findings are important to consider when implementing mobile phone–based programs in diverse populations.

This study has important limitations. First, it was an observational cohort study without a control group or a text messaging only arm, which limits the ability to establish causality. Second, although racially diverse, this study population was commercially insured and relatively well educated, which may limit generalizability, particularly to vulnerable health populations where these interventions may be most needed. Third, long-term follow-up is lacking, which will be important to assess in future studies to understand whether these interventions result in sustained behavior change. Nonetheless, this study has several strengths, including the use of validated behavioral assessments at multiple time points and semi-structured interviews to more fully explore the behavioral effects of the program and minimize observer bias.

Summary and Implications

Findings indicated that among adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, a theory-driven mobile phone intervention led to improvements in diabetes self-care and multiple behavioral constructs including self-efficacy, social support, and health beliefs. As a low-cost and widely available technology, mobile phones are already recognized as a readily scalable platform for addressing chronic diseases. This study suggests further that they can also be a successful and versatile tool for behavior change and may represent a powerful adjunct to traditional diabetes education. Diabetes educators can provide a foundation of knowledge from which interactive programs such as CareSmarts work to sustain further knowledge gains and behavioral changes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research for their individual contributions to this research.

Funders: SN was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Services Research Training Program (T32 HS00084). This research was also supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (R18DK083946), the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK092949), the Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60 DK20595), and the Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes of the Merck Foundation.

Footnotes

Contributors: SN assisted in designing and conducting the study and wrote the manuscript. AM and PH assisted in data collection and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. SML designed the statistical analyses and analyzed the data. MS assisted in intervention design and data collection. MEP designed and conducted the study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. In addition, SN, AM, PH, MS, and MEP participated in coding and analysis of participant interviews. MEP is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentations: Parts of this research study will be presented as a poster presentation at the American Diabetes Association’s 73rd Scientific Sessions in Chicago, Illinois, June 2013.

Conflicts of Interest: SN previously cofounded and was part owner of mHealth Solutions, LLC, a mobile health software company, but since October 2011 has had no financial relationship or affiliation with the company. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Clement S. Diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(8):1204–1214. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.8.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(5):619–629. doi: 10.1177/0145721712455997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1159–1171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duke SA, Colagiuri S, Colagiuri R. Individual patient education for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD005268. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005268.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AG. Culturally appropriate health education for type 2 diabetes mellitus in ethnic minority groups. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD006424. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006424.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):56–69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith A. Mobile Access 2010. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV, Ganesh N, Davern ME, Boudreaux MH. Wireless substitution: state-level estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010-2011. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012;(61):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrick K, Griswold WG, Raab F, Intille SS. Health and the mobile phone. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishna S, Boren SA, Balas EA. Healthcare via cell phones: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2009;15(3):231–240. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn CC, Shardell MD, Terrin ML, Barr EA, Ballew SH, Gruber-Baldini AL. Cluster-randomized trial of a mobile phone personalized behavioral intervention for blood glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):1934–1942. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley WT, Rivera DE, Atienza AA, Nilsen W, Allison SM, Mermelstein R. Health behavior models in the age of mobile interventions: are our theories up to the task? Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(1):53–71. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry JP, Neff RA. Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(2):e16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psych. 2010;29(1):1–8. doi: 10.1037/a0016939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nundy S, Dick JJ, Solomon MC, Peek ME. Developing a behavioral model for mobile phone-based diabetes interventions. PEC. 2013;90(1):125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nundy S, Dick JJ, Goddu AP, et al. Using mobile health to support the chronic care model: developing an institutional initiative. Int J Telemed Appl. 2012;2012:871925. doi: 10.1155/2012/871925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nundy S, Dick JJ, Chia-Hung C, Nocon RS, Chin MH, Peek ME. Mobile phone diabetes project led to improved glycemic control and net savings for Chicago plan participants. Health Affairs. 2014;33(2):1–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(5):348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Cohen HW, Shmukler C, Ullman R, Rivera CM, Walker EA. Measurements of medication adherence in diabetic patients with poorly controlled HbA(1c) Diabet Med. 2010;27(2):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarkar U, Fisher L, Schillinger D. Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy? Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):823–829. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Fisher L, Chesla CA. A contextual model of control beliefs, behavior, and health: Latino and European Americans with type 2 diabetes. Psychol Health. 2003;18:18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker EA, Mertz CK, Kalten MR, Flynn J. Risk perception for developing diabetes: comparative risk judgments of physicians. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(9):2543–2548. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker EA, Caban A, Schechter CB, et al. Measuring comparative risk perceptions in an urban minority population: the risk perception survey for diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(1):103–110. doi: 10.1177/0145721706298198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patino AM, Sanchez J, Eidson M, Delamater AM. Health beliefs and regimen adherence in minority adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(6):503–512. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker EA, Schechter CB, Caban A, Basch CE. Telephone intervention to promote diabetic retinopathy screening among the urban poor. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang TS, Brown MB, Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Social support, quality of life, and self-care behaviors among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(2):266–276. doi: 10.1177/0145721708315680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna S, Boren SA. Diabetes self-management care via cell phone: a systematic review. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(3):509–517. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(12):1332–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffith LS, Field BJ, Lustman PJ. Life stress and social support in diabetes: association with glycemic control. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;20(4):365–372. doi: 10.2190/APH4-YMBG-NVRL-VLWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garay-Sevilla ME, Nava LE, Malacara JM, et al. Adherence to treatment and social support in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 1995;9(2):81–86. doi: 10.1016/1056-8727(94)00021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aljasem LI, Peyrot M, Wissow L, Rubin RR. The impact of barriers and self-efficacy on self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2001;27(3):393–404. doi: 10.1177/014572170102700309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harvey JN, Lawson VL. The importance of health belief models in determining self-care behaviour in diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26(1):5–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, Snoek FJ, Matthews DR, Skovlund SE. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study. Diabet Med. 2005;22(10):1379–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panja S, Starr B, Colleran KM. Patient knowledge improves glycemic control: is it time to go back to the classroom? J Investig Med. 2005;53(5):264–266. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.53509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wardle J, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(6):440–443. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: a comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addict Behav. 1982;7(2):133–142. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]