Abstract

Patient: Male, 21

Final Diagnosis: NUT midline carcinoma

Symptoms: Fatigue • fever • pain

Medication: Romidepsin

Clinical Procedure: Chemotherapy

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

NUT midline carcinoma (NMC) is a rare, highly lethal malignancy that results from a chromosome translocation and mostly arises in the midline organs. To date, no treatment has been established. Most patients receive combinations of chemotherapy regimens and radiation, and occasionally subsequent resection; nevertheless, patients have an average survival hardly exceeding 7 months.

Case Report:

A 21-year-old patient was admitted to our division with a large mediastinal mass with lung nodules, multiple vertebral metastases, and massive nodal involvement. In a few days, the patient developed a superior vena cava syndrome and an acute respiratory failure. Due to the rapid course of the disease, based on preliminary histology of poorly differentiated carcinoma, a dose-dense biweekly chemotherapy with paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin was started. In the meantime, the diagnosis of NMC was confirmed. A surprising clinical benefit was obtained after the first cycle of chemotherapy, and after 6 cycles a PET-CT scan showed a very good response. At this point, radiotherapy was started but the disease progressed outside of the radiation field. The patient entered into a compassionate use protocol with Romidepsin, but a PET/CT scan after the first course showed disease progression with peritoneal and retroperitoneal carcinosis. A treatment with Pemetrexed was then started but the patient eventually died with rapid progressive disease.

Conclusions:

Our case history adds some interesting findings to available knowledge: NMC can be chemosensitive and radiosensitive. This opens the possibility to study more aggressive treatments, including high-dose consolidation chemotherapy and to evaluate the role of biological agents as maintenance treatments.

MeSH Keywords: Antineoplastic Agents; Carcinoma; Mediastinal Neoplasms; Translocation, Genetic

Background

NUT midline carcinoma (NMC) is a rare, highly lethal malignancy that results from a chromosome translocation and arises in the midline organs. The most common translocation is the t(15;19)(q14;p13.1) with bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4)-NUT oncogene expression [1,2], but less frequently, the NUT gene is fused to a different gene, the bromodomain-containing protein 3 (BRD3) gene with the t(15;9) (q14;q34). Moreover, a novel fusion oncogene involving the Human Nuclear SET domain-containing protein 3 (NSD3) and the NUT protein has been recently described [3]. It has been suggested that the fusion proteins block epithelial-squamous differentiation, maintaining the proliferation of immature neo-plastic elements [4].

In 1991, Kubonishi et al. described the first case of NUT midline cancer in a woman with a presumed thymic carcinoma refractory to chemotherapy and radiotherapy [5]. In that case, diagnosis was retrospectively made, because NMC was only identified as a distinct clinic-pathological entity at the beginning of the last decade [6,7]. Currently, the tumour is usually diagnosed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or by demonstrating >50% nuclear staining with the now available NUT monoclonal antibody, which has proven to be highly specific and sensitive for the diagnosis of NMC [8,9].

To date, there is no still established treatment for NMC. Most patients receive combinations of multidrug chemotherapy regimens and radiation, and occasionally subsequent resection. Anthracycline, cisplatin, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and taxane-based chemotherapies have been introduced [10,11], but durable responses are lacking and patients have an average survival hardly exceeding 7 months [12,13]. On the basis of the involvement of bromodomain-containing NUT fusion proteins that cause aberrant histone acetylation and blockade of differentiation, histone deacetylase inhibitors and bromodomain inhibitors are under investigation in clinical trials [14,15].

In our case report we describe a surprising clinical response to dose-dense chemotherapy with paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin.

Case Report

A 21-year-old patient was seen by a family practitioner for a 1-month history of fatigue, fever, and increasing right-sided chest pain. Medical and family histories were unremarkable with no specific risk factors. The first chest radiograph performed showed a right superior lobe atelectasia and a widening of the mediastinum, suggestive of a hilar mass.

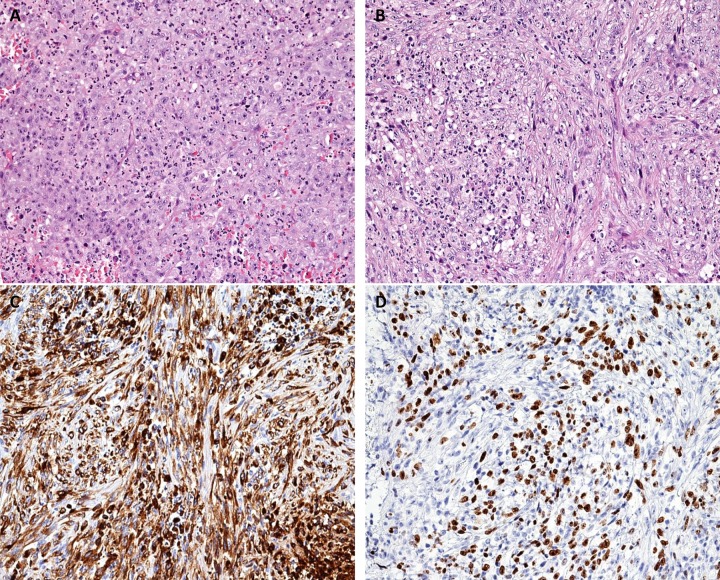

Following a rapid and progressive worsening of chest pain and the appearance of palpable supraclavicular and axillary lymph nodes, on day +7 from the first physical examination, the patient was admitted to our division. A total-body CT scan revealed a large (13.5×8 cm) right anterior upper mediastinal mass with extension into the right lobe, right lung nodules of less than 1.5 cm in size, multiple vertebral tumour infiltrates, and massive nodal involvement to the right supraclavicular, axillary, and mediastinal regions (Figure 1). Multiple focal areas of fluorodeoxyglucose uptake were documented in all the abnormal sites by positron emission tomography (PET). A core biopsy of a supraclavicular lymph node showed a poorly differentiated carcinoma with a high mitotic index.

Figure 1.

The first chest CT scan performed at the admission at the Division of Medical Oncology revealed a large (13.5×8 cm) right anterior upper mediastinal mass with extension into the right lobe.

In few days the patient rapidly progressed with clinical signs and symptoms of a superior vena cava syndrome (VCS), which was promptly treated with steroids and placement of a caval stent. On day +25 the clinical conditions worsened with an acute respiratory failure due to a complete tracheal and right upper bronchus obstruction and pleural effusion requiring endobronchial prothesis and pleural drainage. Due to the rapid course of the disease, based on preliminary histology of poorly differentiated carcinoma, a dose-dense biweekly chemotherapy with paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 d1), ifosfamide (2.5 g/m2 d1–3 plus mesna), and cisplatin (70 mg/m2 d2) along with rhG-CSF rescue was started.

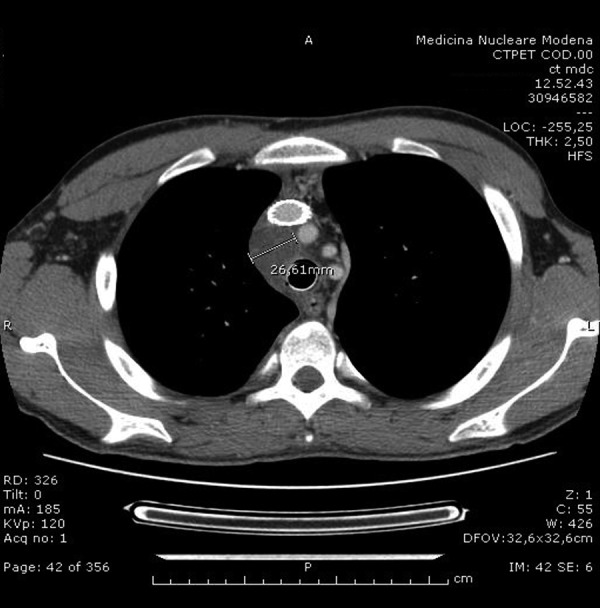

In the meantime, more detailed histochemical analyses were completed describing a mixture of necrotic and viable cells of variable size with high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and MIB-1 expression of approximately 60%. The majority of cells were dyshesive, with some focal cohesive growth pattern and no clear differentiation (Figure 2). A focal positivity was detected for cytokeratin 7 (CK7), Mouse Monoclonal Anti-Cytokeratin 1 Antibody (MNF116), protein 63 (p63), CD10, and CD34. Molecular testing for the SYT gene rearrangement (18q11.2) by FISH, for the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (EBER probe) by in situ hybridization (ISH), for mutational status of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) (exons 18,19,21) and the Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog (K-RAS) (exon 2) were all negative. On the basis of the clinical presentation, the rapid disease course and the histology, a diagnosis of NMC was suggested. Thus, NUT-fusion protein expression linked to the translocation t(15;19) was tested by a specific anti-NUT antibody. The immunohistochemistry confirmed the hypothesis with 80% of nuclei showing a positive signal.

Figure 2.

On hematoxylin-eosin staining, the neoplasia consisted of round (A ×20) and spindle (B ×20) atypical cells of large size, with prominent nucleoli, expressing cytokeratins (poorly differentiated carcinomas). Cytokeratins are pointed out by monoclonal broad spectrum antibody MNF116 and by monoclonal anticytokeratin antibody CK7 (C ×20), directed against low-molecular weight cytokeratins. The immunoreaction for anti-NUT (nuclear protein in testis) is positive in most of neoplastic cells (D ×20).

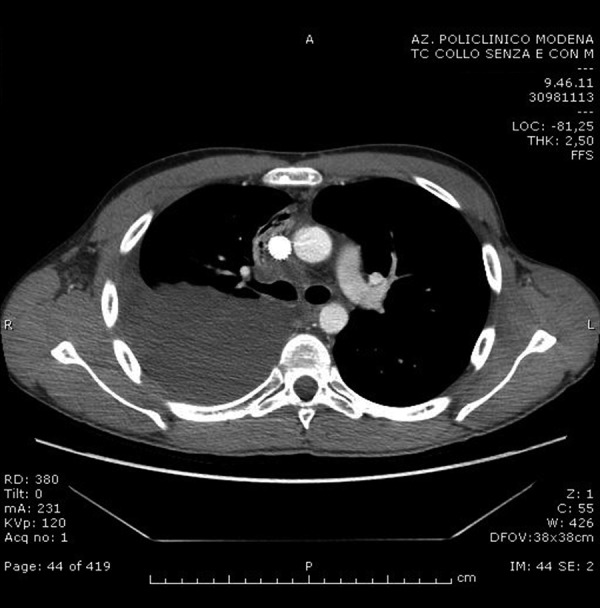

Surprisingly, a relevant clinical benefit was obtained after the first cycle of chemotherapy, with a progressive disappearance of palpable nodes and an improvement of all symptoms. The patient received a total of 6 dose-dense treatments with an expected hematological toxicity. At the end of chemotherapy, a total-body PET-CT scan showed a very good partial response with a reduction of the mediastinal bulk (2.6×1.8 cm), a complete disappearance of lung lesions and pleural effusion, and a significant reduction of pathological nodes (Figure 3). The superior mediastinal residual disease had a moderate dyshomogeneous fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.

Figure 3.

The chest CT scan performed at the end of the dose-dense chemotherapy showed a very good partial response, with a reduction of the mediastinal bulk (2.6×1.8 cm).

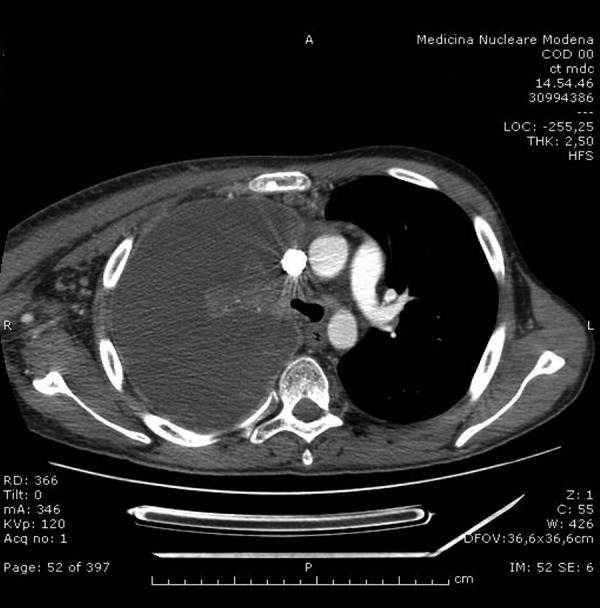

Thirty-five days after the last cycle of chemotherapy, the patient started a radiation treatment targeting the initial mediastinal tumour area with a dose of 2 Gy/daily. Unfortunately, after 18 days and a total dose administered of 28 Gy, the patient was admitted to the hospital with worsening chest pain and dyspnea. A new CT scan documented disease progression mainly outside of the radiation field with right pleural effusion, peritoneal and retroperitoneal involvement, increase of bone lesions, and multiple subcutaneous nodules, but the initial mediastinal mass was still decreasing in size (Figure 4). At that time, considering that the pleural effusion was unilateral and the disease was progressing in several sites, we considered the fluid as a malignant pleural effusion, thus a diagnostic thoracentesis was not performed.

Figure 4.

The chest CT scan performed a few weeks after the end of radiotherapy on the initial mediastinal tumour area documented disease progression with right pleural effusion while the initial mediastinal mass was still decreasing in size.

Because of the rapid progression, based on pre-clinical data and after approval by the Local Ethics Committee, the patient stopped radiotherapy and entered into a compassionate use protocol with Romidepsin, a potent histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. The Local Ethics Committee approved the compassionate use also on the basis of some preliminary encouraging data obtained with another HDAC inhibitor (Vorinostat) (French C., personal communication at that time and now on ref. [15]). Therefore, the patient received weekly intravenous doses of Romidepsin (14 mg/mq) for 3 doses. No significant toxicities were observed, but a PET/CT scan after the first course showed disease progression to the pleural ring, in the subcutaneous areas, nodal involvement, peritoneal and retroperitoneal carcinosis, and new bone lesions (Figure 5). On the basis of the pattern of progression suggestive for mesothelioma-like behavior, an empirically based treatment with Pemetrexed (500 mg/mq every 3 weeks) was started. Unfortunately, the disease further progressed very rapidly and the patient eventually died after 1 course of Pemetrexed.

Figure 5.

The chest CT scan performed after the first course of Romidepsin showed disease progression to the pleural ring and in the subcutaneous areas, and nodal involvement.

Discussion

When our patient was diagnosed with NMC, only 28 cases were reported in the literature and no successful treatment was yet identified [16]. According to the preliminary diagnosis of undifferentiated carcinoma with high proliferative rate, we chose a dose-dense chemotherapy with Taxol, ifosfamide, and cisplatin delivered bi-weekly. After the first cycle of chemotherapy, a significant clinical benefit was reported and during the next 5 cycles a progressive and considerable improvement was observed. Successive radiotherapy to the residual bulky mass was begun until extra-mediastinal progression.

Only a single case with a bone localized NMC has been reported without disease at 34 months after diagnosis [17]. The patient was misdiagnosed in 1991 for a Ewing sarcoma and thus was treated with a combined modality therapy based on vincristine, doxorubicin, and ifosfamide alternating with cisplatin, doxorubicin, and ifosfamide [18]. During cycles 1 and 2, hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy was also administered to the tumor area. This case suggests that intensified regimens may generate a stable benefit for NMC, partially validating our strategy and explaining the early results obtained in our patient. Unfortunately, a number of questions about the choice of chemotherapy treatment and proper timing still remain open.

This rapidly growing tumor demonstrated a surprising clinical response to dose-dense chemotherapy. Particularly, the tumor showed a chemosensitivity profile comparable to that observed for Ewing sarcomas and germ cell tumors. These findings suggest a role for high-dose chemotherapy, possibly with stem cell transplantation, as a therapeutic option in NMC, as in fact previously described for Ewing sarcoma [19,20] and for germ cell tumors [21,22]. Based on these considerations, our patient’s hematopoietic stem cells were mobilized and harvested, but the extremely rapid disease progression did not allow performing any high-dose chemotherapy program. It must be noted, however, that NUT cells can positively stain for CD34 and this might compromise the identification of tumor cells in the grafts.

Our case history also questions the role and timing of radiation therapy. Our patient received radiotherapy after 35 days from the end of chemotherapy and during the treatment the tumour progressed largely outside the radiation field and spread to distant sites. Interestingly, a case report of NMC treated with concomitant hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy and chemotherapy has been published [17], suggesting the possibility of treating the primitive tumor mass and controlling the systemic disease at the same time.

The very good partial response obtained with dose-dense chemotherapy in our patient raises the possibility of evaluating the efficacy of maintenance treatments with either prolonged and less toxic chemotherapy or biological agents. Based on a previous limited clinical experience with an FDA-approved HDAC inhibitor in a child with NUT midline carcinoma (French C., personal communication at that time and now ref. [15]), we decided to treat our patient with Romidepsin. Romidepsin is currently being studied in a variety of tumors and in 2009 it was been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Unfortunately, in this case the treatment with Romidepsin was ineffective, possibly because of primary resistance to the drug or secondary resistance mechanisms, including parallel pathway activation, overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl2 protein, drug-induced de novo genetic variations, or target protein/gene change.

Conclusions

The optimal treatment for NMC has still to be defined, partly because of the rarity of the disease. Our case history adds some interesting findings to the available information: NMC can be, at least in part, chemosensitive and radiosensitive. This opens the possibility to study more aggressive treatments, including high-dose consolidation chemotherapy, and to evaluate the role of maintenance treatments with biological agents such as HDAC inhibitors or bromodomain inhibitors.

References:

- 1.French CA. Demystified molecular pathology of NUT midline carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2008;63:492–96. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.052902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang R, You J. Mechanistic Analysis of the Role of Bromodomain-containing Protein 4 (BRD4) in BRD4-NUT Oncoprotein-induced Transcriptional Activation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(5):2744–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.600759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.French CA, Rahman S, Walsh EM, et al. NSD3-NUT fusion oncoprotein in NUT midline carcinoma: implications for a novel oncogenic mechanism. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(8):928–41. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French CA, Ramirez CL, Kolmakova J, et al. BRD-NUT oncoproteins: a family of closely related nuclear proteins that block epithelial differentiation and maintain the growth of carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2008;27(15):2237–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubonishi I, Takehara N, Iwata J, et al. Novel t(15;19)(q15;p13) chromosome abnormality in a thymic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1991;51(12):3327–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French CA, Kutok JL, Faquin WC, et al. Midline carcinoma of children and young adults with NUT rearrangement. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4135–39. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French CA, Miyoshi I, Kubonishi I, et al. BRD4-NUT fusion oncogene: a novel mechanism in aggressive carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63(2):304–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haack H, Johnson LA, Fry CJ, et al. Diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma using a NUT-specific monoclonal antibody. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(7):984–91. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318198d666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon LW, Magliocca KR, Cohen C, Müller S. Retrospective analysis of nuclear protein in testis (NUT) midline carcinoma in the upper aerodigestive tract and mediastinum. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(2):213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engleson J, Soller M, Panagopoulos I, et al. Midline carcinoma with t(15;19) and BRD4-NUT fusion oncogene in a 30-year-old female with response to docetaxel and radiotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueki H, Maeda N, Sekimizu M, et al. A case of NUT midline carcinoma with complete response to gemcitabine following cisplatin and docetaxel. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36(8):e476–80. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura H, Tsuta K, Tsuda H, et al. NUT midline carcinoma of the mediastinum showing two types of poorly differentiated tumor cells: A case report and a literature review. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211(1):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer DE, Mitchell CM, Strait KM, et al. Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of NUT midline carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5773–79. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirguet O, Gosmini R, Toum J, et al. Discovery of epigenetic regulator I-BET762: lead optimization to afford a clinical candidate inhibitor of the BET bromodomains. J Med Chem. 2013;56(19):7501–15. doi: 10.1021/jm401088k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz BE, Hofer MD, Lemieux ME, et al. Differentiation of NUT midline carcinoma by epigenomic reprogramming. Cancer Res. 2011;71(7):2686–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stelow EB. A review of NUT midline carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;5:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0235-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertens F, Wiebe T, Adlercreutz C, et al. Successful treatment of a child with t(15;19)-positive tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(7):1015–17. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elomaa I, Blomqvist CP, Saeter G, et al. Five-year results in Ewing’s sarcoma. The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group experience with the SSG IX protocol. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:875–80. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari S, Sundby Hall K, Luksch R, et al. Nonmetastatic Ewing family tumors: high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue in poor responder patients. Results of the Italian Sarcoma Group/Scandinavian Sarcoma Group III protocol. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(5):1221–27. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelhardt M, Zeiser R, Ihorst G, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in adult patients with high-risk or advanced Ewing and soft tissue sarcoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beausoleil M, Ernst DS, Stitt L, et al. Consolidative high-dose chemotherapy after conventional-dose chemotherapy as first salvage treatment for male patients with metastatic germ cell tumours. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6(2):111–16. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suleiman Y, Siddiqui BK, Brames MJ, et al. Salvage therapy with high-dose chemotherapy and peripheral blood stem cell transplant in patients with primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(1):161–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]