Abstract

Patient: Male, 66

Final Diagnosis: Ameloblastic carcinoma

Symptoms: Jaw pain

Medication: None

Clinical Procedure: Surgical resection

Specialty: Head and neck surgery

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Ameloblastic carcinoma secondary type is an extremely rare and aggressive odontogenic neoplasm that exhibits histological features of malignancy in primary and metastatic sites. It arises through carcinomatous de-differentiation of a pre-existing ameloblastoma or odontogenic cyst, typically following repeated treatments and recurrences of the benign precursor neoplasm. Identification of an ameloblastic carcinoma, secondary type presenting with histologic features of malignant transformation from an earlier untreated benign lesion remains a rarity. Herein, we report 1 such case.

Case Report:

A 66-year-old man was referred for management of a newly diagnosed ameloblastic carcinoma. He underwent radical surgical intervention comprising hemimandibulectomy, supraomohyoid neck dissection, and free-flap reconstruction. Final histologic analysis demonstrated features suggestive of carcinomatous de-differentiation for a consensus diagnosis of ameloblastic carcinoma, secondary type (de-differentiated) intraosseous.

Conclusions:

Ameloblastic carcinoma, secondary type represents a rare and challenging histologic diagnosis. Radical surgical resection with adequate hard and soft tissue margins is essential for curative management of localized disease.

MeSH Keywords: Ameloblastoma, Mandibular Osteotomy, Neck Dissection, Odontogenic Tumors

Background

Ameloblastic carcinoma is a rare, aggressive, odontogenic epithelial malignancy with significant growth and metastatic potential that demands radical surgical intervention and vigilant post-operative surveillance. In the updated World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of Head and Neck tumors (2005), ameloblastic carcinoma is categorized into three main subtypes; primary type, secondary type (dedifferentiated) intraosseous and secondary type (dedifferentiated) peripheral [1]. Primary tumors arise de novo, whereas the secondary type represents malignant transformation of a pre-existing well-differentiated ameloblastoma or odontogenic cyst. We present a rare case of mandibular ameloblastic carcinoma, secondary type (de-differentiated) intraosseous in a previously untreated ameloblastoma.

Case Report

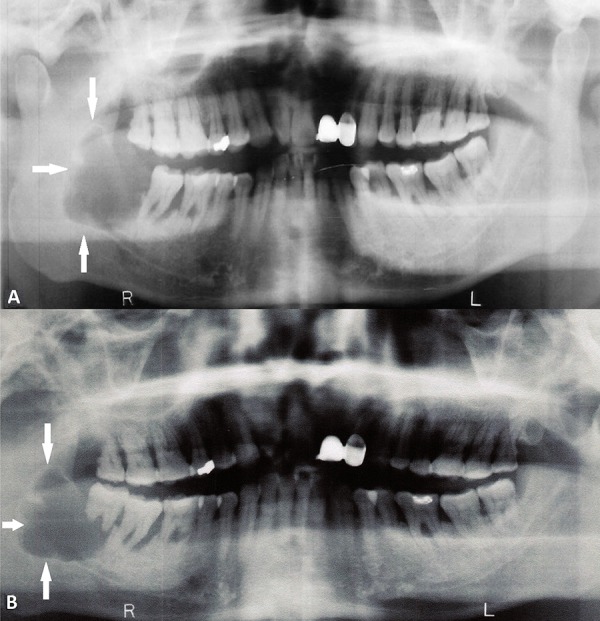

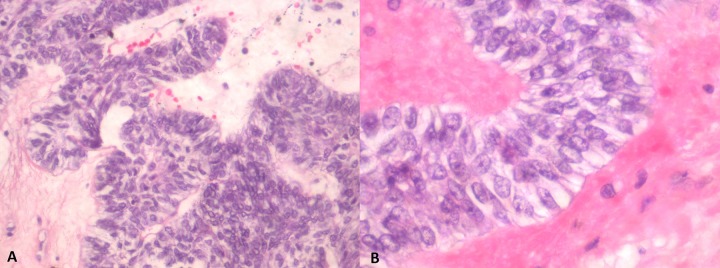

A 66-year-old man was referred to the senior author (G.J.M.) for treatment of a newly diagnosed ameloblastic carcinoma. Prior to his referral, the patient had undergone extensive dental review (in January 2013) for right jaw discomfort which had developed in the months following extraction of the right mandibular third molar (tooth 48). Examination at the time had revealed a cystic mass in the region of teeth 47 and 48 with associated periodontal disease but without extra-oral swelling or trismus. Orthopantomograph (OPG) (Figure 1A) and computed tomography confirmed a large, well defined, multilocular, radiolucent lesion in the right hemi-mandible (measuring 31×1.8×2.7 mm), expanding into and thinning both lingual and buccal cortices. Through further investigation, we identified the same lesion on an OPG taken in June 2012 (Figure 1B), prior to tooth 48 extraction, but it was not investigated at that time. An initial incisional biopsy (in March 2013) demonstrated a plexiform pattern of ameloblastomatous epithelium, exhibiting vacuolated cytoplasm, reverse polarity, and mitoses numbering <1/10 high-power field (Figure 2). A diagnosis of ameloblastoma, favoring the unicystic type, was made by a private pathologist. The following month, the patient underwent the first stage of conservative surgical treatment which included teeth 46 and 47 extraction and cyst decompression. A repeat biopsy was performed at this time. Histologic examination of this tissue revealed an ameloblastic carcinoma. Further radical surgery was proposed, prior to which the patient underwent staging imaging that did not demonstrate evidence of regional or distant metastases.

Figure 1.

Panoramic radiograph demonstrating a large, scalloped, well-defined, lucent lesion of the right mandible (arrows) in (A) January 2013 and (B) June 2012.

Figure 2.

(A) Ameloblastoma with tumor cells exhibiting a plexiform growth pattern. (B) Ameloblastic tumour cells exhibiting characteristic reverse nuclear polarization and subnuclear vacuolation of the cytoplasm.

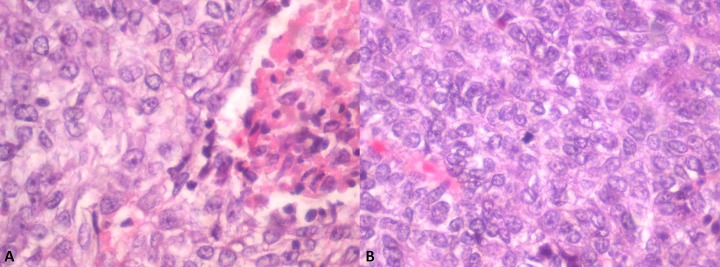

In June 2013, the patient underwent a right supraomohyoid neck dissection, right hemi-mandibulectomy (condyle sparing) via a midline lip-split, and right anterolateral thigh free-flap reconstruction for defect closure. Bony reconstruction was not considered appropriate given his performance status, habitus, and co-morbidities. Gross pathological review of the resected hemi-mandible revealed a variegated cream-to-tan colored tumor (measuring 23×21 mm) that expanded into the bone beneath the ulcerated mucosa. Microscopic examination confirmed the diagnosis of an ameloblastic carcinoma with features supportive of carcinomatous change (ex ameloblastoma). The tumor cells demonstrated peripherally palisading plexiform trabeculae, significant pleomorphism with frequent mitoses (> 12/10 high-power field), and areas of focal necrosis and chronic inflammation (Figure 3). Lymphovascular and perineural permeation was not apparent. All resected margins were clear and there was no evidence of nodal involvement. As such, no adjuvant treatment was required. The patient has remained free of disease in the 18 months of follow-up with OPG imaging at 12 months demonstrating no evidence of mandibular recurrence (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

(A) Ameloblastic carcinoma with area of necrosis. (B) Ameloblastic carcinoma with tumor cells exhibiting crowding, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic activity.

Figure 4.

Post-operative panoramic radiograph (June 2014) demonstrating an absent right mandible lateral to tooth 45 and no evidence of recurrent pathology adjacent to margins of resection.

Discussion

The term ameloblastic carcinoma was introduced by Shafer et al. (1974) [2] to describe a tumor derived from the malignant transformation of the epithelial cells of an ameloblastoma. The distinction between ameloblastic carcinoma and malignant ameloblastoma has been the subject of considerable deliberation and variable classification in past years [1,3–5]. Current separation of these 2 entities is based upon the metastatic yet well-differentiated, benign histology of malignant ameloblastomas in both primary and metastatic sites compared to the cytological atypia exhibited by ameloblastic carcinomas [1].

Ameloblastic carcinomas account for approximately 2% of odontogenic tumors, [6,7] and only 104 cases were reported between 1984 and 2009 [8]. As less than 1% of ameloblastomas undergo malignant transformation, the secondary type is much rarer than the primary type. Periodic reviews of the literature by a number of authors regarding the secondary type have yielded significantly varying aggregates, reflecting the paucity of cases and inconsistency in classification [8–10]. The archetypal ameloblastic carcinoma secondary type exhibits multiple recurrences and carcinomatous de-differentiation from an ameloblastoma subjected to repeated surgical resections. Thus, identification of a secondary type presenting with histologic features of malignant transformation from an untreated benign lesion portends a difficult diagnosis and remains a rarity. To the best of our knowledge, only 6 cases of such an occurrence have been documented in the literature thus far, with our patient representing the seventh [3,9,11–14]. Yoshioka et al. (2013) [15] reported an additional case in which atypical components on tumor enucleation 1 month following initial biopsy diagnosis of ameloblastoma was suggestive of an untreated underlying ameloblastic carcinoma secondary type in favor of rapid carcinomatous dedifferentiation, but no definitive conclusions were drawn.

A consensus histologic criterion for ameloblastic carcinoma remains elusive. Hall et al. (2007) [16] described parameters to aid in the diagnosis, including the presence of sheets, islands, or trabeculae of epithelium and the absence of stellate reticulum-like areas. Additional features of malignancy included hyperchromatism, large or atypical nucleoli, an increased mitotic index, necrosis, calcification, and neural and vascular invasion. As demonstrated in this case and noted by other authors, the lack of uniform cellular atypia in this malignancy and examination of limited tissue specimens often predispose to an erroneous diagnosis [12].

Little is known of the pathogenesis of ameloblastic carcinoma secondary type. Malignant transformation of ameloblastomas may occur spontaneously or following chemotherapy or adjuvant radiotherapy [17]. Karakida et al. (2010) [9] inferred that chronic inflammation post-surgery instigated malignant transformation. Slater (2004) [18] proposed a multistep carcinogenesis and designated the term ‘atypical ameloblastoma’ for ameloblastomas that demonstrated basilar hyperplasia and an increased mitotic index, as these features were insufficient for a diagnosis of ameloblastic carcinoma in the absence of nuclear pleomorphism, perineural invasion, or other histologic evidence of malignancy. In our case, we are unable to accurately comment on the chronicity of the underlying neoplasm. The only available earlier imaging were radiographs in the region of teeth 46 to 48 (December 2005 and July 2007, respectively), from which evidence of gingival involvement could not be discerned. The lack of noticeable tumor growth between June 2012 and January 2013 likely reflects carcinomatous change occurring over many years.

Without intervention, ameloblastic carcinoma (all types) runs an aggressive course with extensive local destruction and metastatic spread. The lung is the most common site of dissemination but metastasis to the brain, bone, liver and regional lymphatic basin have also been described [8]. No treatment consensus yet exists; however, wide local excision with adequate hard and soft tissue margins appears to be the most commonly supported algorithm. As in our case, a contiguous neck dissection should be undertaken for diagnostic staging and therapeutic purposes. Adjuvant radiotherapy for close or positive margins or in those with nodal metastases may be beneficial, but chemotherapy regimens have no evidence of benefit. As these tumors are prone to recur, a meticulous and lengthy follow-up with systematic assessment and periodic imaging, particularly of the chest, is justified.

Conclusions

This report describes an ameloblastic carcinoma, secondary type (dedifferentiated) intraosseous, arising in a previously undiagnosed ameloblastoma of the right mandible with histologic illustration of benign to malignant transition. The patient underwent successful curative radical surgical resection and is alive without disease at 18 months of follow-up.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Jeanne Tomlinson for her professional opinion on the histological specimens. Dr. Muzib Abdul-Razak for his surgical expertise.

Footnotes

Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

References:

- 1.Sciubba JJ, Eversole LR, Slootweg PJ. Odontogenic/ameloblastic carcinomas. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, et al., editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 287–89. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shafer W, Hine M, Levy B. A textbook of Oral Pathology. 4th ed. USA: WB Saunders; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slootweg PJ, Muller H. Malignant ameloblastoma or ameloblastic carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:168–76. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elzay RP. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaws. Review and update of odontogenic carcinomas. Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:299–303. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruse AL, Zwahlen RA, Gratz KW. New classification of maxillary ameloblastic carcinoma based on an evidence-based literature review over the last 60 years. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:31. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jing W, Xuan M, Lin Y, et al. Odontogenic tumours: a retrospective study of 1642 cases in a Chinese population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladeinde AL, Ajayi OF, Ogunlewe MO, et al. Odontogenic tumours: a review of 319 cases in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:191–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon HJ, Hong SP, Lee JI, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma: an analysis of 6 cases with review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:904–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karakida K, Aoki T, Sakamoto H, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma, secondary type: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:e33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Du H, Li P, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma: An analysis of 12 cases with a review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:914–20. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suomalainen A, Hietanen J, Robinson S, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma of the mandible resembling odontogenic cyst in a panoramic radiograph. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:638–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abiko Y, Nagayasu H, Takeshima M, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma ex ameloblastoma: report of a case-possible involvement of CpG island hypermethylation of the p16 gene in malignant transformation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita S, Anami M, Satoh N, et al. Cytopathologic features of secondary peripheral ameloblastic carcinoma: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:354–58. doi: 10.1002/dc.21427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamath VV, Satelur K, Yerlagudda K. Spindle cell variant of ameloblastic carcinoma arising from an unicystic amelobastoma: Report of a rare case. Dent Res J. 2012;9:328–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshioka Y, Toratani S, Ogawa I, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma, secondary type, of the mandible: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:e58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall JM, Weathers DR, Unni KK. Ameloblastic carcinoma: an analysis of 14 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akrish S, Buchner A, Shoshani Y, et al. Ameloblastic carcinoma: report of a new case, literature review, and comparison to ameloblastoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:777–83. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slater LJ. Odontogenic malignancies. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am. 2004;16:409–24. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]