Abstract

This investigation describes the relationship between TBI patient demographics, quality of life outcome, and functional status outcome among clinic attendees and non-attendees. Of adult TBI survivors with intracranial hemorrhage, 63 attended our TBI clinic and 167 did not attend. All were telephone surveyed using the Extended-Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE), the Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI) scale, and a post-discharge therapy questionnaire. To determine risk factors for GOSE and QOLIBRI outcomes, we created multivariable regression models employing covariates of age, injury characteristics, clinic attendance, insurance status, post-discharge rehabilitation, and time from injury. Compared with those with severe TBI, higher GOSE scores were identified in individuals with both mild (odds ratio [OR]=2.0; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1–3.6) and moderate (OR=4.7; 95% CI: 1.6–14.1) TBIs. In addition, survivors with private insurance had higher GOSE scores, compared with those with public insurance (OR=2.0; 95% CI: 1.1–3.6), workers' compensation (OR=8.4; 95% CI: 2.6–26.9), and no insurance (OR=3.1; 95% CI: 1.6–6.2). Compared with those with severe TBI, QOLIBRI scores were 11.7 points (95% CI: 3.7–19.7) higher in survivors with mild TBI and 17.3 points (95% CI: 3.2–31.5) higher in survivors with moderate TBI. In addition, survivors who received post-discharge rehabilitation had higher QOLIBRI scores by 11.4 points (95% CI: 3.7–19.1) than those who did not. Survivors with private insurance had QOLIBRI scores that were 25.5 points higher (95% CI: 11.3–39.7) than those with workers' compensation and 16.8 points higher (95% CI: 7.4–26.2) than those without insurance. Because neurologic injury severity, insurance status, and receipt of rehabilitation or therapy are independent risk factors for functional and quality of life outcomes, future directions will include improving earlier access to post-TBI rehabilitation, social work services, affordable insurance, and community resources.

Key words: : neurologic function outcome, quality of life outcome, rehabilitation, TBI clinic, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Follow-up care for TBI patients is often fragmented after discharge from acute inpatient treatment.1,2 Vanderbilt's interdisciplinary TBI clinic is one approach to maintaining contact with TBI patients; the clinic provides an opportunity for patients to meet with a multi-specialty team to address long-term sequelae (e.g., fatigability, depression, irritability, insomnia, and cognitive deficits). Attendees receive cognitive and mental health screenings, a physical examination, and a health-related quality of life assessment. Patients, along with accompanying family members and caregivers, are provided information and referrals to resources that may be important to their recovery, such as support groups, rehabilitation, driver evaluation and training, and other community services that are available to assist in the long-term management of TBI-related sequelae. Although this clinic is provided as a no-charge follow-up appointment, many TBI patients do not attend.

The primary aim of this investigation is to identify any differences in the population of patients who attended our no-cost TBI follow-up clinic, compared with those who did not. We hypothesized that the population of patients who attended the follow-up clinic experienced more severe trauma and higher neurologic injury burden, and thus had a greater need for follow-up services. Because this clinic is no-charge, we hypothesized that those without insurance are more likely to attend, as they will have had less opportunity to pursue services elsewhere. Additionally, we hypothesized that those who attended the clinic experienced more functional impairment and poorer quality of life as a result of brain injury. The secondary aim of this investigation is to describe the relationship between TBI patient demographics, quality of life, and functional outcomes among clinic attendees and non-attendees.

Methods

Study population

This institutional review board–approved, retrospective cohort study included adult TBI survivors. The eligible study population included those who experienced a TBI as evidenced by intracranial hemorrhage on head computed tomography (CT) and were admitted to a single Level I trauma center from July 2010 through May 2012. All patients who survived to discharge were offered a three-month, no-charge appointment at the multidisciplinary TBI clinic. Exclusion criteria were individuals younger than 18 years old at time of hospital admission, non–English speaking individuals, vulnerable populations (such as prisoners or pregnant women), those not entered into the Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons (e.g., readmissions), and those who were unable to be contacted by telephone.

We defined non-contact by telephone as no working phone number or four failed attempts at contact across the following time frames: early morning (6 a.m. to 8 a.m.), morning (8 a.m. to noon), afternoon (1 p.m. to 5 p.m.), or evening (6 p.m. to 8 p.m.). Multiple time frames were used in order to obviate the conflict of work or personal responsibilities as the cause of non-contact.

Procedures

All participants were administered a telephone survey incorporating a measure of orientation, the Extended-Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE), the Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI) scale, and a questionnaire covering demographic information and receipt of post-discharge rehabilitation. The telephone survey was completed either by the individual with TBI, a surrogate (relative, friend, or caregiver), or both.

The Extended-Glasgow Outcome Scale is a 19-item functional status questionnaire that yields a score ranging from 1 (deceased) to 8 (upper good recovery). The GOSE has been repeatedly validated as an informative and accurate assessment tool in TBI.3,4 The QOLIBRI scale is a 37-item questionnaire with six subscales that measure quality of life in the domains of cognition, self, daily life and autonomy, social relationships, emotions, and physical problems. This tool has been internationally validated in the TBI population.5,6

From the trauma registry, we extracted patients' mechanism of injury (blunt, penetrating), admission Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, Injury Severity Score (ISS), and demographic data, including age, sex, race, and insurance status. Although GCS score can be treated as a continuous variable, in order to avoid model overfitting, to address non-normal distribution, and to use common clinical categorization, GCS score was categorized into mild (13–15), moderate (9–12), and severe (3–8) levels of injuries.4,7 ISS is defined as the additive square value of the three highest (i.e., most severe) Abbreviated Injury Scores; ISS reflects trauma severity and ranges from 1 to 75, with 75 indicating the most severe injury.8 We classified insurance status into the following four categories: private (PPO, HMO, and auto), public (Medicaid, Medicare, TennCare, and military), workers' compensation, and no insurance.

To identify factors that predicted clinic attendance, we created a multivariable logistic regression model employing covariates of age, sex, insurance status, and baseline injury characteristics (mechanism of injury, ISS, and admission GCS score). To determine risk factors for long-term functional and quality of life outcomes, as measured by GOSE and QOLIBRI at the time of phone follow-up, we developed multivariable regression models employing covariates of age, sex, insurance status, baseline injury characteristics (injury mechanism, GCS score, and ISS), clinic attendance, post-discharge rehabilitation, and time from injury to completion of telephone survey. All data was maintained using REDCap, a secure database hosted at Vanderbilt University.9

Results

Sample characteristics

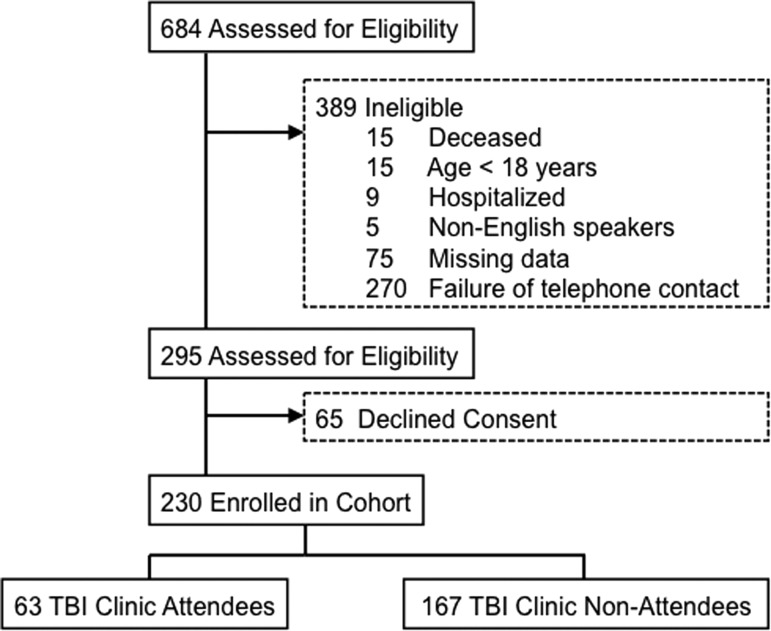

Of the 684 patients scheduled for a clinic appointment, 295 met eligibility criteria. Of these 295 eligible participants, 65 were successfully reached by phone but refused consent. The remaining 230 participants consented and thus represented the final cohort for this study; 63 attended our TBI clinic and 167 did not attend (Fig. 1). Full cohort characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Of the 230 interviews, 200 (87.0%) were completed by the survivor alone, six (2.6%) with the help of a relative, friend, or caregiver, and 24 (10.4%) by the relative, friend, or caregiver alone. A relative, friend, or caregiver provided assistance or acted as a proxy-responder when the survivor was unable to answer the questions due to a cognitive or physical (speech) impairment.

FIG. 1.

Eligibility criteria.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of TBI Clinic Attendees Versus Non-Attendees

| Variable | TBI clinic attendees (n=63) | TBI clinic non-attendees (n=167) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 44 (IQR, 27–56) | 44 (IQR, 25–59) | 0.8061 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 75% (47) | 66% (111) | 0.2352 |

| Male | 25% (16) | 34% (56) | |

| Race | 0.6862 | ||

| White | 94% (59) | 87% (146) | |

| Black | 6% (4) | 11% (18) | |

| Hispanic | 0% (0) | <1% (1) | |

| Asian | 0% (0) | <1% (1) | |

| American Indian | 0% (0) | <1% (1) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 51% (32) | 52% (86) | 0.0122 |

| Public | 24% (15) | 29% (49) | |

| Uninsured | 11% (7) | 16% (27) | |

| Workers compensation | 14% (9) | 3% (5) | |

| Mechanism | |||

| Blunt | 92% (58) | 98% (165) | 0.0232 |

| Penetrating | 8% (5) | 2% (2) | |

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) category | |||

| Mild (score 13–15) | 59% (37) | 60% (101) | 0.9712 |

| Moderate (score 9–12) | 6% (4) | 4% (11) | |

| Severe (score 3–8) | 35% (22) | 36% (56) | |

| Injury Severity Score (ISS) | 22 (IQR, 16–33) | 25 (IQR, 17–34) | 0.2071 |

| Post-TBI rehabilitation | |||

| No | 75% (47) | 74% (124) | 0.9572 |

| Yes | 25% (16) | 26% (43) | |

| Days since TBI | 383 (IQR, 232–522) | 305 (IQR, 170–473) | 0.0402 |

| Extended-Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE) | |||

| Lower severe disability | 19% (12) | 17% (29) | 0.7762 |

| Upper severe disability | 10% (6) | 13% (21) | |

| Lower moderate disability | 14% (9) | 10% (16) | |

| Upper moderate disability | 22% (14) | 18% (30) | |

| Lower good recovery | 21% (13) | 24% (40) | |

| Upper good recovery | 14% (9) | 19% (31) | |

| Quality of Life After Brain Injury (QOLIBRI) scale | 65 (IQR, 42–84) | 72 (IQR, 51–90) | 0.0801 |

Descriptors are either percent (frequency) or median (interquartile range, 25%-75%)

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

Pearson chi2 test

TBI, traumatic brain injury; IQR, interquartile range.

Clinic attendance

Results of the univariate comparisons between clinic attendees and non-attendees indicated that clinic attendees differed by insurance status, mechanism of injury, and time to phone call follow-up (see Table 1). Results of the multivariable logistic regression on clinic attendance indicated that those with worker's compensation were more likely to attend clinic, compared with individuals with private insurance (odds ratio [OR]=4.2; 95% CI: 1.3–14.1). There was a non-significant trend among individuals who sustained a penetrating injury, where they were more likely to attend clinic than those who sustained a blunt injury (OR=4.5; 95% CI: 0.9–22.0). Age, sex, public insurance, no insurance, ISS, and admission GCS score did not independently predict clinic attendance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable Ordered Logistic Regression Model Predictors of Clinic Attendance

| Patient Characteristics | Odds Ratio for Higher GOSE | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.0 [95% CI: 1.0 – 1.0] | 0.957 |

| Gender | ||

| Female versus male | 1.3 [95% CI: 0.7 – 2.7] | 0.423 |

| Mechanism | ||

| Penetrating versus blunt | 4.5 [95% CI: 0.9 – 22.0] | 0.062 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score category | ||

| Mild versus severe | 0.7 [95% CI: 0.3 – 1.5] | 0.353 |

| Moderate versus severe | 0.6 [95% CI: 0.2 – 2.8] | 0.571 |

| Injury Severity Score (ISS) | 1.0 [95% CI: 0.9 – 1.0] | 0.245 |

| Insurance status | ||

| Public versus private | 0.8 [95% CI: 0.4 – 1.7] | 0.559 |

| Uninsured versus private | 0.5 [95% CI: 0.2 – 1.5] | 0.238 |

| Workers' compensation versus private | 6.6 [95% CI: 1.8 – 24.1] | 0.004 |

| Received post-discharge rehabilitation | 0.7 [95% CI: 0.3 – 1.5] | 0.343 |

| Follow-up time (in days) post-TBI | 1.00 [95% CI: 1.0 – 1.0] | 0.180 |

GOSE, Extended-Glasgow Outcome Scale; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Functional outcome

Results of the multivariable ordinal logistic regression on GOSE scores indicated that admission GCS score and insurance status were independent predictors of functional outcome (Table 3). Compared with those with severe TBI, GOSE scores were more likely to be higher among individuals with mild TBI (OR=2.0; 95% CI: 1.1–3.6) and moderate TBI (OR=4.7; 95% CI: 1.6–14.1). Additionally, participants with private insurance were more likely to have higher GOSE scores than those with public insurance (OR=2.0; 95% CI: 1.1–3.6), workers' compensation (OR=8.1; 95% CI: 2.6–26.9), or no insurance (OR=3.1; 95% CI: 1.6–6.2). Age, sex, injury mechanism, injury severity score, clinic attendance, receipt of post-discharge rehabilitation, and time to phone call follow-up were not predictors of functional outcome.

Table 3.

Multivariable Ordered Logistic Regression Model Predictors of GOSE Scores

| Patient characteristics | Odds ratio for higher GOSE | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.0 [95% CI: 1.0 – 1.0] | 0.218 |

| Gender | ||

| Female versus male | 1.1 [95% CI: 0.7 – 1.9] | 0.668 |

| Insurance status | ||

| Public versus private | 2.0 [95% CI: 1.1 – 3.6] | 0.023 |

| Uninsured versus private | 3.1 [95% CI: 1.6 – 6.2] | 0.001 |

| Workers' compensation versus private | 8.4 [95% CI: 2.6 – 26.9] | 0.000 |

| Mechanism | ||

| Penetrating versus blunt | 1.4 [95% CI: 0.4 – 4.9] | 0.617 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score category | ||

| Mild versus severe | 2.0 [95% CI: 1.1 – 3.6] | 0.019 |

| Moderate versus severe | 4.7 [95% CI: 1.6 – 14.1] | 0.005 |

| Injury Severity Score (ISS) | 1.0 [95% CI: 1.0 – 1.0] | 0.168 |

| Received post-discharge rehabilitation | 1.0 [95% CI: 0.6 – 1.8] | 0.975 |

| Clinic attendance | ||

| Attendee versus non-attendee | 0.8 [95% CI: 0.5 – 1.4] | 0.533 |

| Follow-up time (in days) post-TBI | 1.0 [95% CI: 1.0 – 1.0] | 0.079 |

GOSE, Extended-Glasgow Outcome Scale; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Quality of life outcome

Results of the multivariable linear regression on QOLIBRI scores indicated that admission GCS score, insurance status, and receipt of post-discharge rehabilitation were independent predictors of quality of life (Table 4). Compared with those with severe TBI, QOLIBRI scores were 11.7 points (95% CI: 3.7–19.7) higher in participants with mild TBI and 17.3 points (95% CI: 3.2–31.5) higher in those with moderate TBI. In addition, participants who received post-discharge rehabilitation had higher QOLIBRI scores by 11.4 points (95% CI: 3.7–19.1). Participants with private insurance had QOLIBRI scores that were 25.5 points (95% CI: 11.3–39.7) higher than those with workers' compensation and 16.8 points (95% CI: 7.4–26.2) higher than those without insurance. There was no difference in quality of life between patients who were publicly or privately insured. Age, sex, injury mechanism, injury severity score, clinic attendance, and time since injury were not risk factors for quality of life outcome.

Table 4.

Multivariable Linear Regression Model Predictors of Higher QOLIBRI Scores

| Patient Characteristics | β [95% CI] | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.1 [95% CI: −0.2 – 0.1] | 0.626 |

| Insurance status | ||

| Public versus private | −6.0 [95% CI: −13.7 to 1.7] | 0.124 |

| Uninsured versus private | −16.8 [95% CI: −26.2 to −7.4] | 0.001 |

| Workers' compensation versus private | −25.6 [95% CI: −39.7 to −11.3] | 0.001 |

| Mechanism | ||

| Penetrating versus blunt | 3.89 [95% CI: −13.41 to 21.20] | 0.658 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) category | ||

| Mild versus severe | 11.7 [95% CI: 3.7 – 19.7] | 0.004 |

| Moderate versus severe | 17.3 [95% CI: 3.2 – 31.5] | 0.017 |

| Injury Severity Score (ISS) | −0.03 [95% CI: −0.4 to 0.3] | 0.850 |

| Received post-discharge rehabilitation | 11.4 [95% CI: 3.7 – 19.1] | 0.004 |

| Clinic attendance | ||

| Attendee versus non-attendee | −6.3 [95% CI: −13.6 to 0.9] | 0.087 |

| Follow-up time (in days) post-TBI | 0.01 [95% CI: −0.004 to 0.031] | 0.136 |

QOLIBRI, Quality of Life After Brain Injury scale; CI, confidence interval; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Discussion

Clinic attendance

In our TBI cohort, individuals carrying workers' compensation, and possibly those with penetrating brain injuries, were significantly more likely to attend clinic. Other demographic and baseline injury characteristics were not associated with clinic attendance. It is likely that patients with workers' compensation attended our clinic more often than other survivors because these individuals often have case managers to coordinate care, as well as possible financial incentives (through return to work or litigation) to have the impact of their injury evaluated. As an interdisciplinary clinic comprised of two trauma surgeons, a nurse practitioner, a social worker, and speech-language pathologists, we are able to easily access patient health information from throughout their inpatient stay at our Level 1 trauma center and provide attendees with a comprehensive evaluation to both corroborate their diagnoses and effectively address the variety of issues that may be preventing them from returning to their previous working capacity.

Previous research indicates that individuals with penetrating brain injuries have higher rates of mortality but they do not differ from blunt brain injuries on long-term functional and quality of life outcomes10 and may have a good prognosis.11 However, rate of medical complications has been found to be higher in individuals with penetrating brain injuries,12 which may explain the greater health care utilization that was observed in our study among this particular population.

Functional and quality of life outcomes

Insurance status was an independent predictor of both functional and quality of life outcomes. Patients with private insurance had better functional outcomes than those with public insurance, workers' compensation, or no insurance and reported better quality of life than those with workers' compensation or no insurance. The association between private insurance and better outcomes could be rationalized if insurance status is a proxy for socioeconomic status, in which privately insured individuals have relatively higher socioeconomic status and, consequently, more access to resources. In contrast, individuals with other forms of insurance (public, workers' compensation or uninsured) may not be equally privy to the same services, due to insurance restrictions or lack of awareness of service availability. Further, patients with private insurance (e.g., employer-sponsored health plan) may not experience the same daily stressors, at least to the same degree, that publicly insured, workers' compensation, and uninsured individuals often encounter, such as unemployment, financial strain, or comorbid chronic health conditions. These findings are reflective of some of the universal issues the national health system is currently facing.

Receipt of post-discharge rehabilitation also was an independent predictor of quality of life; patients who received rehabilitation services indicated higher quality of life but did not demonstrate any difference in functional status from patients who did not receive post-discharge rehabilitation. These results are consistent with an investigation examining unmet needs of 1830 individuals living in the community one-year post-TBI. More than half of the individuals without health insurance reported unmet service needs and were found to have poorer satisfaction with life.13 With these findings in mind, we included an exploratory question regarding the need for rehabilitation in our follow-up phone interview. Of the 230 patients who participated in our study, 110 (48%) individuals felt they needed rehabilitation, yet 65 (59%) of them had not received any.

Unsurprisingly, severity of brain injury, as measured by admission GCS score, was an independent predictor of both functional and quality of life outcomes, such that patients with either mild or moderate traumatic brain injuries reported better functional status and higher quality of life, compared with those with severe TBI. Specifically, moderate TBI patients reported the best functional and quality of life outcomes, superior even to the mild TBI group on both the GOSE and QOLIBRI scales. A possible explanation for this unexpected finding is that patients who have sustained a mild brain injury, as opposed to a moderate one, might be more aware of any cognitive-communicative impairments and more capable of comparing these deficits with their pre-injury baseline; thus, mild TBI patients may perceive their own recovery less favorably and, because of this self-awareness, be more likely to experience psychological and behavioral difficulties.

Limitations

The results of this study should be considered within the context of the methodological limitations. Long-term follow-up is a common challenge to studies of the TBI population. It is thought that those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged are less likely to be available for follow up.14 In this study, the individuals we successfully contacted were comparable in age, race, insurance status, mechanism of injury, and injury severity (ISS and GCS) to those we were unable to reach. However, women were overrepresented in those we were able to contact, compared with those we were unable to contact. Thus, our dataset may not be wholly representative of other TBI communities. Our ability to follow-up with all eligible participants was constrained by current phone contact information and lack of multi-modal contact methods. Due to this form of sampling bias, there may be an obscured underlying relationship between phone accessibility and long-term outcomes.

Additionally, receipt of rehabilitation post-hospital discharge was recorded using a dichotomous response, without an opportunity to specify the type (i.e., speech-language, physical, occupational) or dose (i.e., amount, frequency, intensity) of rehabilitation received. However, even with the dichotomous responses, receipt of any therapy was an independent predictor of quality of life.

Finally, our phone follow-up did not investigate reasons for clinic non-attendance. Non-attendance may be a result of either poor prognosis among severe TBI patients or, conversely, high work attendance for individuals with good recovery. Clinic attendance may also be influenced by availability of transportation, or appointment overload and communication. Future studies would greatly benefit from further exploring these reasons for non-attendance so that TBI clinics, like our own, can identify, and therefore sufficiently mitigate, potential obstacles to attendance.

Conclusions

We show a difference in patterns of insurance, characterized by higher rates of attendance among those with workers' compensation and improved outcomes for privately insured individuals. Post-discharge rehabilitation also was predictive of patients' reported quality of life. Taken together, these results could have significant public health implications for the TBI population, in which quality of care disparities are linked to patients' form of payment. Because insurance status and receipt of rehabilitation are risk factors for long-term outcomes, future directions should include improving earlier access to post-TBI rehabilitation, social work services, affordable insurance, and community resources. Although our clinic did not appear to be an independent predictor of outcomes, the clinic may provide a point of contact to either increase access to insurance and/or outpatient rehabilitation through referrals to social work and community-based services. Partnering with services and institutions specializing in cognitive, speech, language, occupational, physical, and psychological therapies will be needed to improve the equity and overall quality of care provided to all TBI patients. Further, our study provides a cross-sectional snapshot of our local TBI patient population and the variables that influence both clinic attendance and outcome measures. With the recent implementation of the Affordable Care Act, and possible future Medicaid expansion in our state of Tennessee, observing any longitudinal changes in TBI patient characteristics, particularly in post-discharge care, may provide valuable insight for our clinic and further illuminate sources for non-attendance and poor long-term outcomes.

In previous studies, GCS score has been found to be a weak predictor of later functional and quality of life outcomes.10,15 Although the findings of this study show that severe TBI as evidenced by admission GCS is associated with poorer functional and quality of life outcomes, future studies that utilize GCS scores throughout the spectrum of care (scene, emergency department, ICU, hospital stay, post-acute care) may provide a more accurate depiction of long-term outcomes. For example, longitudinal GCS scores would lessen the impact of unmeasured confounders at the time of admission, such as patient factors (e.g., intoxication, drug ingestions) or provider factors (e.g., paralytics for airway or operative management).16 Moreover, integrating in-hospital variables in a statistical model may identify additional modifiable pharmacologic agents, laboratory biomarkers, and behavioral risk factors, which would not only be helpful for improving specialized TBI clinics but also the entire TBI patient system of care.

Lastly, our cohort was based on a real world, all-comers model that included patients with a wide range injuries, health care needs, and resources, not just from one GCS category,17 or an exclusive rehabilitation research cohort (e.g., TBI Model Systems)16 but more importantly, our TBI clinic demonstrated successful collaboration across multiple medical specialties to offer our patients the most comprehensive services. This study illustrates the critical nature of continuous care coordination and follow-up of TBI patients, and our findings will provide the clinic with more defined criteria to guide organization and interventions that are more directly tailored to meet the needs of our local TBI patients, their families and caregivers.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. Disclosure of financial support: AHRQ Health Services 5T32HS013833-08, AHRQ (MBP); Vanderbilt Physician-Scientist Development Grant (MBP); REDCap, UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH (all authors).

References

- 1.Jeyaraj J.A., Clendenning A., Bellemare-Lapierre V., Iqbal S., Lemoine M.C., Edwards D., and Korner-Bitensky N. (2013). Clinicians' perceptions of factors contributing to complexity and intensity of care of outpatients with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 27, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langlois J.A., Rutland-Brown W., and Wald M.M. (2006). The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin H.S., Boake C., Song J., McCauley S., Contant C., Diaz-Marchan P., Brundage S., Goodman H., and Kotrla K.J. (2001). Validity and sensitivity to change of the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale in mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 18, 575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichol A.D., Higgins A.M., Gabbe B.J., Murray L.J., Cooper D.J., and Cameron P.A. (2011). Measuring functional and quality of life outcomes following major head injury: common scales and checklists. Injury 42, 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinbüchel von N., Wilson L., Gibbons H., Hawthorne G., Höfer S., Schmidt S., Bullinger M., Maas A., Neugebauer E., Powell J., Wild von K., Zitnay G., Bakx W., Christensen A.-L., Koskinen S., Sarajuuri J., Formisano R., Sasse N., and Truelle J.L.; QOLIBRI Task Force. (2010). Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI): scale development and metric properties. J. Neurotrauma 27, 1167–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinbüchel von N., Wilson L., Gibbons H., Hawthorne G., Höfer S., Schmidt S., Bullinger M., Maas A., Neugebauer E., Powell J., Wild von K., Zitnay G., Bakx W., Christensen A.-L., Koskinen S., Formisano R., Saarajuri J., Sasse N., Truelle J.L.; QOLIBRI Task Force. (2010). Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI): scale validity and correlates of quality of life. J. Neurotrauma 27, 1157–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennett B. (2002). The Glasgow Coma Scale: history and current practice. Trauma 4, 91–103 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker S.P., O'Neill B., Haddon W., and Long W.B. (1974). The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J. Trauma 14, 187–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., and Conde J.G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42, 377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zafonte R.D., Mann N.R., Millis S.R., Wood D.L., Lee C.Y., and Black K.L. (1997). Functional outcome after violence related traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 11, 403–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gressot L.V., Chamoun R.B., Patel A.J., Valadka A.B., Suki D., Robertson C.S., and Gopinath S.P. (2014). Predictors of outcome in civilians with gunshot wounds to the head upon presentation. J. Neurosurg. 121, 645–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black K.L., Hanks R.A., Wood D.L., Zafonte R.D., Cullen N., Cifu D.X., Englander J., and Francisco G.E. (2002). Blunt versus penetrating violent traumatic brain injury: frequency and factors associated with secondary conditions and complications. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 17, 489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickelsimer E.E., Selassie A.W., Sample P.L., W Heinemann A., Gu J.K., and Veldheer L.C. (2007). Unmet service needs of persons with traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 22, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corrigan J.D., Harrison-Felix C., Bogner J., Dijkers M., Terrill M.S., and Whiteneck G. (2003). Systematic bias in traumatic brain injury outcome studies because of loss to follow-up. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 84, 153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King J.T., Carlier P.M., and Marion D.W. (2005). Early Glasgow Outcome Scale scores predict long-term functional outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 22, 947–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker M.D., Whyte J., Pretz C.R., Sherer M., Temkin N., Hammond F.M., Saad Z., and Novack T. (2014). Application and clinical utility of the Glasgow coma scale over time: a study employing the NIDRR traumatic brain injury model systems database. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 29, 400–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vikane E., Hellstrøm T., Roe C., Bautz-Holter E., Assmus J., and Skouen J.S. (2014). Missing a follow-up after mild traumatic brain injury–does it matter? Brain Inj. 28, 1374–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]