Abstract

The packaging capacity of recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vectors limits the size of the promoter that can be used to express the 4.43-kb cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) cDNA. To circumvent this limitation, we screened a set of 100-mer synthetic enhancer elements, composed of ten 10-bp repeats, for their ability to augment CFTR transgene expression from a short 83-bp synthetic promoter in the context of an rAAV vector designed for use in the cystic fibrosis (CF) ferret model. Our initial studies assessing transcriptional activity in monolayer (nonpolarized) cultures of human airway cell lines and primary ferret airway cells revealed that three of these synthetic enhancers (F1, F5, and F10) significantly promoted transcription of a luciferase transgene in the context of plasmid transfection. Further analysis in polarized cultures of human and ferret airway epithelia at an air–liquid interface (ALI), as well as in the ferret airway in vivo, demonstrated that the F5 enhancer produced the highest level of transgene expression in the context of an AAV vector. Furthermore, we demonstrated that increasing the size of the viral genome from 4.94 to 5.04 kb did not significantly affect particle yield of the vectors, but dramatically reduced the functionality of rAAV-CFTR vectors because of small terminal deletions that extended into the CFTR expression cassette of the 5.04-kb oversized genome. Because rAAV-CFTR vectors greater than 5 kb in size are dramatically impaired with respect to vector efficacy, we used a shortened ferret CFTR minigene with a 159-bp deletion in the R domain to construct an rAAV vector (AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR). This vector yielded an ∼17-fold increase in expression of CFTR and significantly improved Cl– currents in CF ALI cultures. Our study has identified a small enhancer/promoter combination that may have broad usefulness for rAAV-mediated CF gene therapy to the airway.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal, autosomal-recessive disorder that affects at least 30,000 people in the United States alone.1 The genetic basis of CF is mutation of a single gene that encodes the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR).2,3 This results in a defective CFTR protein and consequent abnormalities in the transport of electrolytes and fluids in multiple organs.4,5 The most life-threatening outcome is CF pulmonary disease, which is characterized by viscous mucous secretions and chronic bacterial infections.6 With improvement in patient care and advances in pharmacologic therapies for CF, the life span of patients with CF has steadily been extended; however, the quality of life for patients with CF remains poor, and medications that alleviate pulmonary complications are expensive and efficacious only in select patients. Because lung disease is the major cause of mortality in patients with CF and the genetic basis is a single-gene defect, gene therapy for CF lung disease has the potential to cure all patients with CF, regardless of their CFTR mutation. Thus, clinical trials for CF lung gene therapy were initiated in the mid-1990s. However, all trials to date have been unsuccessful.7 The underlying reason is that the vectors available for gene transfer to the human airway epithelium (HAE) are inefficient.8–10

Adeno-associated virus (AAV), a member of the human parvovirus family, is a nonpathogenic virus that depends on helper viruses for its replication. For this reason, rAAV vectors are among the most frequently used in gene therapy preclinical studies and clinical trials.11–13 Indeed, CF lung disease clinical trials with rAAV2 demonstrated both a good safety profile and long persistence of the viral genome in airway tissue (as assessed by biopsy) relative to other gene transfer agents (such as recombinant adenovirus). Nevertheless, gene transfer failed to improve lung function in patients with CF because transcription of the rAAV vector-derived CFTR mRNA was not detected.14–17 These observations are consistent with later studies on rAAV transduction using an in vitro model of the polarized HAE, in which the cells are grown at an air–liquid interface (ALI).18,19 The poor efficiency of rAAV2 as a vector for CFTR expression in the HAE is largely due to two major barriers: (1) inefficient postentry processing of the virus, and (2) the limited packaging capacity of rAAV.

The initial preclinical studies with rAAV2-CFTR that supported the first clinical trial in patients with CF were performed in rhesus monkeys. These studies demonstrated that viral DNA and transgene-derived CFTR mRNA persisted in the lung for long periods after rAAV2-mediated CFTR gene transfer.20 However, later studies comparing the efficiency of rAAV2 transduction between human and rhesus monkey airway epithelial ALI cultures demonstrated that the tropism of rAAV2 for apical transduction was significantly higher in the rhesus monkey cultures than in their human counterparts21—likely due to species-specific differences in the AAV2 receptors and coreceptors that exist on the apical surface. In studies of polarized HAE, the majority of AAV2 virions were internalized after apical infection, but accumulated in the cytoplasm rather than entering the nucleus.18,22 One obstacle to the intracellular trafficking required for productive viral transduction is the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway18,23; transient inhibition of proteasome activity dramatically enhances transduction (700-fold) of rAAV2-luciferase vectors from the apical surface by facilitating translocation of the vector to the nucleus.24 However, the application of proteasome inhibitors to enhance transduction efficiency of rAAV-CFTR vectors only marginally improves CFTR expression, most likely due to the low activity of the short promoter used in the rAAV-CFTR vectors.25 The open reading frame (ORF) of the CFTR gene is 4.443 kb, and thus approaches the size of the 4.679-kb AAV genome. Although the AAV capsid can accommodate content in excess of its native DNA genome, its maximal packaging capacity is approximately 5.0 kb,26 and transgene expression from vectors exceeding this limit have significantly reduced function.27 Given the requirements for 300 bp of cis elements from the AAV genome (two inverted terminal repeat [ITR] sequences at the termini) and the 4443-bp CFTR coding sequence, there is little space left in the vector genome (257 bp) for a strong promoter and polyadenylation signal. Thus, the first-generation rAAV-CFTR vector (AV2.tgCF) that was tested in clinical trials relied on the cryptic promoter activity of the AAV2 ITR to drive transcription of the full-length CFTR cDNA with a synthetic polyadenylation signal.28,29

More recently, we developed a new rAAV vector, AV2.tg83-CFTR, which uses an 83-bp synthetic promoter (tg83)25 to improve expression of the full-length human CFTR cDNA. The genome of this vector is 4.95 kb in size. Although this vector produced a 3-fold increase in cyclic AMP (cAMP)-mediated Cl– currents in CF HAE ALI cultures relative to AV2.tgCF, this level of expression remained suboptimal for application in CF gene therapy. Other groups have attempted to use a CFTR minigene to create space for incorporating a better promoter into the rAAV vectors; this seemed justified on the basis of earlier studies of CFTR gene function and structure indicating that the deletion of short, nonessential sequences from the C terminus and regulatory domain (R domain) had only minimal effects on the chloride channel function of CFTR.30 One widely used CFTR minigene is CFTRΔR, which lacks 156 bp encoding 52 amino acid residues (708–759) at the N terminus of the R domain. Gene transfer with a recombinant adenoviral vector encoding CFTRΔR in CF HAE ALI cultures demonstrated that this transgene retains at least 80% of the transepithelial Cl– transport supported by full-length CFTR.31 In addition, the expression of CFTRΔR in CFTR–/– knockout mice rescued the lethal intestinal phenotype.32 This 156-bp deletion made it possible to package an rAAV CFTR expression vector 4.94 kb in length, with expression driven by a minimal cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (173 bp), into an AAV5 capsid.33 Additional efforts were aimed at developing AAV variant vectors of higher apical tropism, through directed evolution of the AAV capsid in polarized HAE ALI cultures.34 However, these rAAV vectors did not provide efficient CFTR expression because the minimal CMV promoter did not function well in fully differentiated airway epithelia.

Despite these advances in rAAV vector design for CF gene therapy, the system has yet to be developed to a point that justifies preclinical studies in animal models that develop spontaneous CF lung disease. Our laboratory established a CFTR knockout ferret model that spontaneously develops a lung phenotype that mirrors key features of human CF disease, including spontaneous bacterial infection of the lung, defective secretion from submucosal glands, diabetes, and gastrointestinal disease.35–39 We have also demonstrated that the airways of newborn ferrets can be efficiently transduced by rAAV1 in the presence of proteasome inhibitors.40 Thus, preclinical studies in the CF ferret model can be initiated as soon as an rAAV vector that effectively expresses CFTR in airway epithelium is generated. To this end, we have attempted to optimize an rAAV vector cassette that efficiently expresses the ferret CFTR (fCFTR) gene.

In this paper we describe the use of short enhancer elements (∼100-mer synthetic oligonucleotide sequences consisting of 10-mer repeats) to enhance gene expression from a minimal promoter in rAAV vectors. These 100-bp enhancer elements were previously identified in a screen of 52,429 unique oligonucleotide sequences, for their ability to activate transcription directed by the CMV immediate-early (IE) minimal promoter in cell lines.41 We hypothesized that the enhancers that are most potent in activating transcription could be used to enhance activity of the synthetic tg83 promoter in airway cells in the context of rAAV vectors. We tested eight combinations of the tg83 promoter and 100-bp synthetic enhancers, and found that one, designated F5, efficiently enhanced transcription from the tg83 promoter in polarized airway cells (in vitro) derived from both humans and ferrets, as well as in the ferret airway (in vivo). Using the F5tg83 promoter and the ferret CFTR minigene with partial deletion at the R domain (fCFTRΔR), we constructed an rAAV vector (AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR) and tested its ability to correct CFTR-mediated Cl– transport in CF ALI cultures.

Materials and Methods

Production of rAAV vectors

All rAAV vector stocks were generated in HEK 293 cells by triple plasmid cotransfection using an adenovirus-free system, and purified by two rounds of CsCl ultracentrifugation as reported previously.42 All the rAAV cis transfer plasmids and enhancer-containing plasmid vectors were propagated in the E. coli SURE strain (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) in order to increase the stability of the long inverted repeats at the termini of the proviral genome and tandem repeat in the enhancer arrays. For all viral vectors and proviral plasmids, rAAV2 genomes were used and packaged into AAV2 or AAV1 capsid to generate rAAV2/2 and rAAV2/1 viruses, respectively. TaqMan real-time PCR was used to quantify the physical titer (DNase-resistant particles [DRP]) of the purified viral stocks as previously described.24,43 The PCR primer–probe set used to titer luciferase vectors was as follows: 5′-TTTTTGAAGCGAAGGTTGTGG-3′ (forward primer), 5′-CACACACAGTTCGCCTCTTTG-3′ (reverse primer), and 5′-FAM-ATCTGGATACCGGGAAAACGCTGGGCGTTAAT-TAMRA-3′ (probe); the primer–probe set used for ferret CFTR vectors was 5′-GACGATGTTGAAAGCATACCAC-3′ (forward primer), 5′-CACAACCAAAGAAATAGCCACC-3′ (reverse primer), and 5′-FAM-AGTGACAACATGGAACACATACCTCCG-TAMRA-3′ (probe). All primers and probes were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The PCR was performed and analyzed with a MyiQ real-time PCR detection system and software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Analysis of integrity of viral genomes

Viral DNA was extracted from 109 DRP of AAV-CFTR vectors and resolved in 0.9% alkaline denatured agarose gel at 20 V overnight in 50 mM NaOH–1 mM EDTA buffer. After transfer to a Nylon membrane, Southern blotting was performed with a 32P-labeled CFTR probe to visualize the viral DNA. For examination of 5′-end genome deletions in the oversized rAAV vectors, 3.33×108 DRP of each virus (quantitated by TaqMan PCR with probe–primer set against fCFTR cDNA) was loaded into a slot-blotting Nylon membrane. The blots were first hybridized to a set of three 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes against the minus strand of the rAAV genome: at the 5′ sequence of the tg83 promoter, taccctcgagaacggtgacgtg; the center of ferret CFTR cDNA, ggagatgcgcctgtctcctggaatg; and the 3′ sequence of the synthetic poly(A), gcatcgatcagagtgtgttggttttttgtgtg. After exposure to X-ray film, the membranes were stripped of probe and hybridized again to another set of three 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes complementary to the plus strand. NIH ImageJ software was used to quantify the signal intensity of hybridization to determine the corresponding number of genomes detected by each probe with serial dilutions of the proviral plasmid as standards.

Cell culture and conditions for transfections and infections

Human airway cell lines A549 and IB3, as well as HEK 293 cells, were cultured as monolayers in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin–streptomycin, and maintained in a 37°C incubator at 5% CO2. Primary ferret airway cells were isolated and cultured as nonpolarized monolayers or at an ALI to generate polarized epithelia as previously described.44 Polarized primary HAE were generated from lung transplant airway tissue as previously described45 by the Cells and Tissue Core of the Center for Gene Therapy at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA). Cells of the CuFi-8 line, a conditionally transformed cell line that was generated from ΔF508/ΔF508 CF airway cells,46 were polarized at an ALI under conditions similar to those used for primary HAE.47 Ferret and human airway epithelia were grown on 12-mm Millicell membrane inserts (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and differentiated with USG medium containing 2% Ultroser G supplement (Pall BioSepra, France) at an ALI before use. Cell lines and primary monolayer cultures of airway cells were transfected with plasmids, using Lipofectamine and 1.0 μg of plasmid. For rAAV infections of A549 cells, and of polarized human or ferret airway epithelial cells, vectors were typically left in the culture medium for 24 hr (A549 cells) or for 16 hr (polarized cells). For apical infection of the polarized HAE ALI cultures, vectors were diluted in USG medium to a final volume of 50 μl and applied to the upper chamber of the Millicell insert. For basolateral infections, vectors were directly added to the culture medium in the bottom chamber. Proteasome inhibitors were supplied in the culture medium throughout the period of infection to polarized cells, at 40 μM LLnL (N-acetyl-l-leucine-l-leucine-l-norleucine) and 5 μM doxorubicin in the case of polarized human cultures, and 10 μM LLnL and 2 μM doxorubicin in the case of CuFi ALI cultures and ferret ALI cultures. Epithelia were exposed to the viruses and chemicals for 16 hr and then removed. At this time, the Millicell inserts were briefly washed with a small amount USG medium and fresh USG medium was added to the bottom chamber only. Doxorubicin was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and LLnL was from Boston Biochem (Cambridge, MA).

rAAV infection of ferret lungs

All animal experimentation was performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa. In vivo infection of ferret lungs was performed by intratracheal injection of a 300-μl inoculum containing 2×1011 DRP of rAAV2/1 and 250 μM doxorubicin. Before infection at 5 days of age, ferret kits were anesthetized by inhalation of a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen. At 8 days postinfection, the animals were killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (intraperitoneal injection). For luciferase expression assays, the ferret trachea and lungs were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then pulverized with a cryogenic tissue pulverizer. One milliliter of passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) was added to the pulverized tissue to extract protein. After four freeze–thaw cycles, the tissue extract was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min, and the clarified tissue extract was used for luciferase assays with a luciferase assay kit from Promega.

Measurement of expression of the firefly luciferase reporter

At the indicated times postinfection or posttransfection, cells were lysed with luciferase cell lysis buffer and luciferase enzyme activity in cell lysates was determined with the Promega luciferase assay system in a 20/20 luminometer equipped with an automatic injector (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA).

Measurement of short-circuit currents

Transepithelial short circuit currents (Isc) were measured with an epithelial voltage clamp (model EC-825) and a self-contained Ussing chamber system (both purchased from Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) as previously described.48 Throughout the experiment the chamber was kept at 37°C, and the chamber solution was aerated. The basolateral side of the chamber was filled with buffered Ringer's solution containing 135 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.2 mM K2HPO4, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. The apical side of the chamber was filled with a low-chloride Ringer's solution in which 135 mM sodium gluconate was substituted for NaCl. Transepithelial voltage was clamped at zero, with current pulses applied every 5 sec and the short-circuit current recorded with a VCC MC8 multichannel voltage/current clamp (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) with Quick DataAcq software. The following chemicals were sequentially added to the apical chamber: (1) amiloride (100 μM), to inhibit epithelial sodium conductance by epithelial sodium channels (ENaCs); (2) 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS, 100 μM), to inhibit non-CFTR chloride channels; (3) the cAMP agonists forskolin (10 μM) and 3-isobutyl-l-methylxanthine (IBMX, 100 μM) to activate CFTR chloride channels; and (4) the CFTR inhibitor GlyH-101 {N-(2-naphthalenyl)-[(3,5-dibromo-2,4-dihydroxyphenyl) methylene] glycine hydrazide; 10 μM} to block Cl– secretion through the CFTR. ΔIsc was calculated by taking the difference of the plateau measurement average over 45 sec before and after each change in conditions (chemical stimulus).

Quantitative analysis of vector-derived CFTR mRNA after transduction with rAAV

The total RNA from rAAV-infected cells was prepared with an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). Because the residual single-stranded DNA rAAV genome in the RNA sample can be an undesirable template for traditional real-time PCR, a modified RNA-specific method for PCR of the rAAV vector49 was used to detect the vector-derived ferret CFTR mRNA. In brief, the first-strand cDNA synthesis was primed with an adapter (lower case)-linked, vector-specific primer that targets the synthetic polyadenylation signal sequence (upper case). The sequence of this primer was 5′-gcacgagggcgacugucaUGAUCGAUGCAUCUGAGCUCUUUAUUA-3′, in which all dTs were replaced with dU. After RNase H digestion was carried out to eliminate the RNA templates, a ferret CFTR-specific primer (5′-TGCAGATGAGGTTGGACTCA-3′) was used for synthesis of the second strand. To avoid false amplification from cDNA produced from the single-stranded viral DNA, all of the dU components in the first- and second-strand cDNA products, as well as the excess adapter primers, were degraded by applying uracyl-N-glycosylase (UNG). Thus, a second-strand cDNA product linked to the complementary sequence of the adapter derived exclusively from rAAV transcripts was produced. The primer set for TaqMan PCR contained the ferret CFTR sequence 5′-CAAGTCTCGCTCTCAAATTGC-3′, and the adapter sequence 5′-GCACGAGGGCGACTGTCA-3′. The TaqMan probe used was 5′-FAM-ACCTCTTCTTCCGTCTCCTCCTTCA-TAMRA-3′.

Results

Synthetic oligonucleotide enhancers that increase tg83 promoter-driven transcription in airway cells

A previous unbiased screen evaluating short synthetic enhancers from a library containing 52,429 unique sequence identified enhancer elements capable of activating transcription from a 128-bp minimal CMV IE promoter (−53 to +75) in HeLa cells.41 This library comprised all possible 10-mer DNA sequences, printed on microarrays as 10 tandem repeats (for a total length of 100 bases each). The best-performing 100-mer oligonucleotides enhanced the transcription of this 128-bp CMV IE minimal promoter to 75–137% of that induced by the 600-bp wild-type CMV IE promoter.41 In previous studies, we used an 83-bp synthetic promoter sequence (tg83) to express the full-length CFTR gene from an rAAV vector (AV2.tg83-CFTR) and found that this promoter produced higher transgene expression in CF HAE cultures than the cryptic promoter of the AAV2 ITR.25 The tg83 promoter consists of an ATF-1/CREB site and an Sp1-binding site from the promoter of the Na,K-ATPase α1 subunit, and the TATA box and transcription start site from the CMV IE promoter. We hypothesized that combining the tg83 promoter with a synthetic enhancer identified through this library screen would produce transcriptional units of greater efficiency in polarized human and/or ferret airway epithelia in vitro and in vivo. To test this possibility, we evaluated the top eight enhancer sequences identified by Schlabach and colleagues (F1, F4, F5, F10, C9, D3, CREB6, and CREB841) for their ability to enhance tg83 transcription in human and ferret airway epithelium.

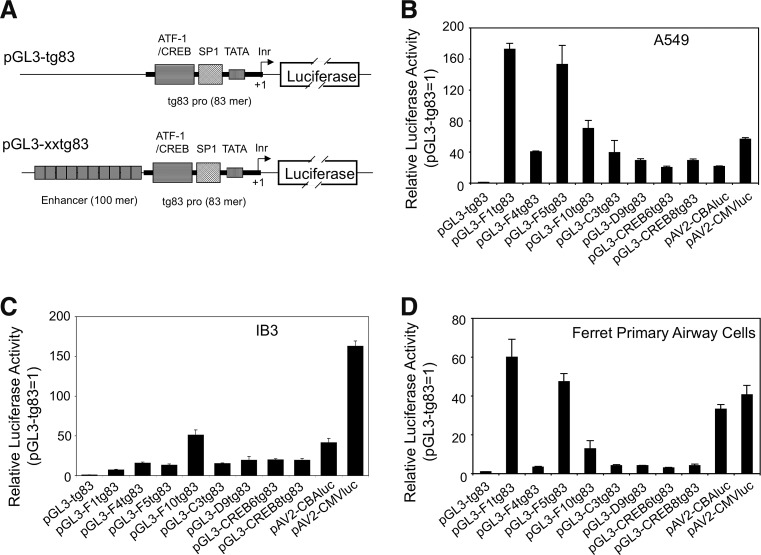

We first cloned the tg83 promoter into the promoter-less luciferase reporter plasmid pGL3-Basic Vector (Promega) to generate pGL3-tg83. Next we constructed a series of luciferase reporter expression plasmids, in which one of the eight 100-mer enhancers was placed in front of the tg83 promoter of pGL3-tg83 (Fig. 1A). Comparison of reporter expression from pGL3-tg83 and its enhancer-containing derivatives was conducted in monolayer (nonpolarized) cultures of two human airway cell lines (A549 and IB3) and primary ferret airway cells (Fig. 1B–D). Two additional luciferase expression plasmids, pAV2-CMV-luc (contains the wild-type, 600-bp CMV IE enhancer-promoter) and pAV2-CBA-luc (contains the CMV IE enhancer-chicken β-actin promoter, i.e., the CBA promoter), were included as controls for high-level promoter activity. Assessment of luciferase expression after plasmid transfection demonstrated that all of the enhancers tested increased tg83-driven luciferase expression, and that their efficiencies varied by cell line: in the human A459 cell and the primary ferret airway cell cultures, F1tg83 and F5tg83 exceeded the activity of the CBA and CMV promoters; and in the human IB3 cell cultures, F10tg83 was most effective but drove far less expression than the CMV promoter (Fig. 1B–D).

FIG. 1.

Effectiveness of synthetic oligonucleotide enhancers in augmenting activity of the tg83-directed luciferase reporter plasmids in monolayer cultures. (A) Schematic structure of the reporter vectors used to screen the enhancer library. The transcriptional motifs of the synthetic tg83 promoter are indicated. (B–D) Reporter activity in monolayer cultures of human airway cell lines (B) A549 and (C) IB3, and (D) a ferret primary airway cell line, after transfection with the indicated plasmids. Luciferase assays were conducted 24 hr posttransfection. Data represent the mean (±SEM, n=3) relative luciferase activity of each transfection normalized to that of the enhancer-less vector pGL3-tg83, whose value in each cell type tested was set to 1.

The F5 element most efficiently enhances tg83-driven transcription in polarized human and ferret airway epithelia in vitro, as well as in the ferret airway in vivo

Because the F1, F5, and F10 enhancers were the most effective in activating tg83-driven transcription in airway cell monolayer cultures, we next evaluated the abilities of these elements to promote transcription in the context of rAAV vector genomes. Four rAAV proviral vectors harboring a luciferase expression cassette were constructed, with expression driven by tg83 (enhancer-less), F1tg83, F5tg83, or F10tg83. The pAV2-tg83-fCFTR proviral plasmid was used as the template vector for cloning; its promoter and the 5′ portion of the fCFTR coding region were replaced with the 2.1- or 2.2-kb luciferase expression cassette. The genome size was 4.75 kb in the case of rAV2.tg83luc, and 4.85 kb for the enhancer-containing vectors. This design was used for two reasons. First, retaining as much of the fCFTR sequence as possible ensured that the vector genome size would be similar to those of the rAAV-CFTR expression vectors that we sought to ultimately generate. Second, retaining regions of the fCFTR cDNA maximized the potential influences of the ferret CFTR sequence on enhancer function.

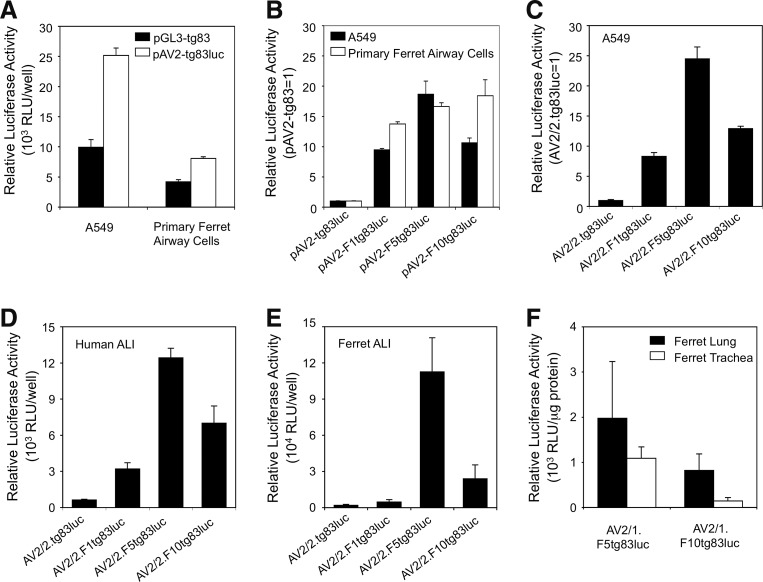

As a first step in investigating whether AAV ITRs and the portion of fCFTR transgene sequence to be tested (i.e., 3′ half of the fCFTR cDNA) influence transcription from the tg83 promoter, we compared reporter expression from pGL3-tg83 and pAV2-tg83luc plasmids after transfection into monolayer cultures of A549 and primary ferret airway cells. pAV2-tg83luc plasmid was found to be 2.5-fold (in A549) and 2-fold (in primary ferret airway cells) more transcriptionally active than the pGL3-based plasmids (Fig. 2A), suggesting that inclusion of the AAV ITR and/or the fCFTR stuffer sequences had an overall positive effect on activity of the tg83 promoter. We then compared reporter gene expression for pAV2-F1tg83luc, pAV2-F5tg83luc, pAV2-F10tg83luc, and pAV-tg83luc plasmids. As expected, the F1, F5, and F10 enhancers significantly improved transcription from the tg83 promoter (∼10- to 19-fold) in both cell types (Fig. 2B). However, the effectiveness of nearly all enhancers was significantly reduced (∼3- to 18-fold) within the rAAV proviral plasmids when compared with pGL3-tg83 plasmids lacking ITRs and the CFTR sequence (Fig. 2B [solid columns] vs. Fig. 1B; Fig. 2B [open columns] vs. Fig. 1D). This suggests that the sequences from the AAV ITR and/or portions of the ferret CFTR cDNA have an overall negative impact on enhancer function. However, this effect on the synthetic enhancers differed between the A549 and ferret primary airway cell monolayers. In A549 cells, the F1 enhancer was most significantly influenced, with its activity in the rAAV proviral plasmid decreased by 18.1-fold, whereas those of the F5 and F10 enhancers decreased by only 8.2- and 3.8-fold, respectively. In primary ferret airway cells, the F1 and F5 enhancers had 4.4- and 2.8-fold decreased activity, respectively, in the context of the proviral plasmid, whereas the function of F10 was slightly enhanced (∼40%).

FIG. 2.

Effectiveness of enhancers F1, F5, and F10 in augmenting activity of the tg83 promoter in the context of proviral plasmids and rAAV. (A) Effect of the AAV2 inverted terminal repeat (ITR) on transcription from the tg83 promoter, as evaluated after transfection of A549 and primary airway ferret cells with pGL3-tg83 or pAV2-tg83luc. Data represent the mean (±SEM, n=3) relative luciferase activity (RLU) 24 hr posttransfection. (B) Effectiveness of enhancers on transcription after transfection of A549 and primary ferret airway cells with the indicated AAV2 proviral plasmids. Data represent the mean (±SEM; n=3) relative luciferase activity of each transfection, normalized to the enhancer-less vector pAV2-tg83luc (set to 1 for each cell type), 24 hr posttransfection. (C) Effectiveness of enhancers on transcription 24 hr after infection of A549 cells with the indicated rAAV2 vectors. Data represent the mean (±SEM; n=3) relative luciferase activity for each infection, normalized to the enhancer-less vector pAV2-tg83luc (set to 1). (D and E) Effectiveness of enhancers on transcription after basolateral infection of polarized (D) human and (E) ferret airway epithelia infected with 2×1010 DRP of the indicated rAAV2 vectors. Data represent the mean (±SEM; n=4) RLU for each condition 2 days postinfection. ALI, air–liquid interface. (F) Effectiveness of enhancers on transcription in lung and tracheal tissue after infection of three ferret pups (5 days old) with 2×1011 DRP of AV2/1.F5tg83luc or AV2/1.F10tg83luc, in the presence of proteasome inhibitors. Luciferase activity was measured 8 days postinfection. Data represent the mean (±SEM; n=3) relative luciferase activity (RLU/μg protein). DRP, DNase-resistant particles.

We next evaluated expression from the various enhancer elements in the context of rAAV2/2 vectors. In A549 cells, similar increases in expressions from the enhancer/tg83 promoter combination were observed after transfection with the proviral plasmid and infection with the corresponding rAAV vector (Fig. 2B [solid columns] vs. Fig. 2C). Primary human and ferret airway epithelial ALI cultures were then infected with equal titers of each rAAV vector, and transgene expression was assessed 2 days postinfection. These experiments demonstrated that F5tg83 is the most efficient promoter in both human and ferret ALI cultures (Fig. 2D and E), leading to 19.6- and 57.5-fold increases, respectively, in tg83-driven transcription over that driven by the enhancer-less control (Fig. 2D and E). Notably, the differentiated state of ferret airway epithelial cells appeared to dramatically influence expression from the various enhancer/tg83 promoter combinations in the context of rAAV transduction; the F5 enhancer more effectively enhanced tg83 expression in the polarized epithelium (Fig. 2E; 57.5-fold) than in undifferentiated monolayers (Fig. 2B; 16.6-fold); the F1 enhancer only marginally increased activity of the tg83 promoter in polarized cells, but increased transgene expression 13.8-fold in monolayer cells.

Last, we compared the in vivo activities of the F5tg83 and F10tg83 promoters in the airways of newborn ferrets, using intratracheal injection of two rAAV1 capsid-pseudotyped vectors (AV2/1.F5tg83luc and AV2/1.F10tg83luc; equal particle titers injected). This capsid serotype had previously been shown to be effective at transducing ferret airways in the presence of a proteasome inhibitor.40 Luciferase activity was measured in extracts prepared from tracheal and lung tissue 8 days postinfection, and F5tg83 was found to be more effective than F10tg3 in transducing both ferret lung and trachea (Fig. 2F). These findings were consistent with those for polarized ferret airway epithelial ALI cultures (Fig. 2E).

A narrow limit for rAAV genome size significantly influences functionality of rAAV-CFTR vectors while not altering packaging efficiency

The size of the expected AV.tg83fCFTR genome if fully packaged is 4.937 kb (Fig. 3A). Incorporation of the F5 enhancer would increase this to 5.040 kb. Although it is well accepted that AAV can encapsidate an rAAV genome slightly longer than its natural size (4.679 kb), gradually increasing the size of an rAAV vector from 4.675 kb to 4.883 and 5.083 kb results in 25 and 75% decreases, respectively, in transduction.26 Furthermore, single-molecule sequencing (SMS) of the two rAAV termini after packaging of a 5.8-kb proviral genome revealed that the 5′ ITR was unstable and had incurred deletions.50 Given that the limits for functional genome packaging in the context of rAAV-CFTR vectors have yet to be defined, we were uncertain whether a 5.04-kb AV.F5tg83fCFTR genome would be compromised with respect to genome stability and function.

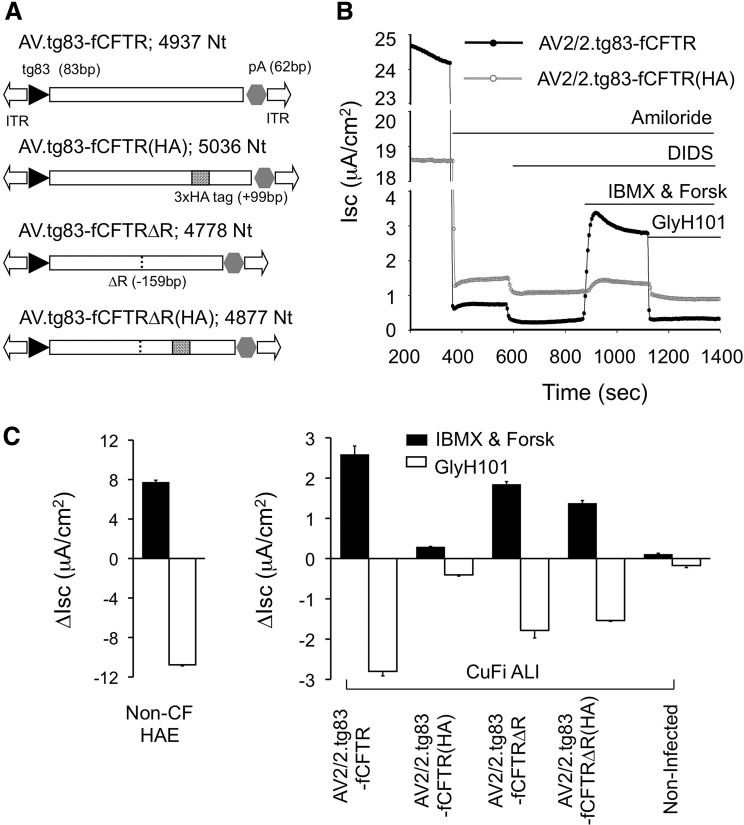

FIG. 3.

Impact of rAAV-CFTR construct size on restoration of CFTR chloride currents in polarized CF airway epithelium. (A) Schematic illustration of structures of rAAV2 vectors of distinct sizes that encode the full-length ferret CFTR open reading frame (ORF) and R domain-deleted variants, under the control of the same transcriptional elements: the 83-bp synthetic promoter (tg83), a 62-bp synthetic polyadenylation signal (pA), a 17-bp 5′ untranslated region (UTR), and a 9-bp 3′ UTR. The ORF of full-length ferret CFTR (fCFTR) is 4455 bp. The 99-bp 3×HA tag was inserted between amino acid residues S900 and I901, bringing fCFTR(HA) to 4554 bp. The fCFTRΔR has a shortened OFR (4296 bp); 53 amino acid residues (I708–P760, 159 bp) are deleted from the R domain. fCFTRΔR(HA) is 4395 bp in length, having a 99-bp HA tag insertion and a 159-bp deletion in the R domain. The functionalities of these vectors on rescue of CFTR-specific Cl– transport (reflected by transepithelial short-circuit currents [Isc]) were compared in differentiated CF HAE ALI cultures, after infection at 1011 DRP per Millicell insert (MOI of ∼105 DRP/cell) in the presence of the proteasome inhibitors LLnL (10 μM) and doxorubicin (2 μM). CF HAE ALI cultures were generated from a conditionally transformed human CF airway cell line (CuFi-8; genotype ΔF508/ΔF508). (B) Typical traces of the Isc changes from CF ALI cultures, infected with the indicated AAV-CFTR vectors, after the sequential addition of various inhibitors and agonists. Amiloride and DIDS were used to block ENaC-mediated sodium currents and non-CFTR chloride channels before addition of cAMP agonist (forskolin and IBMX), and GlyH-101 was used to block CFTR-specific currents. ΔIsc (IBMX and Forsk) reflects the activation of CFTR-mediated chloride currents after induction with cAMP agonist, and ΔIsc (GlyH-101) reflects the inhibition of CFTR-mediated chloride currents after addition of GlyH-101. (C) Effects of vector size on rescue of chloride Isc currents. rAAV-CFTR vectors were increased by ∼100-bp increments. Shown are the ΔIsc (IBMX and Forsk) and ΔIsc (GlyH-101) responses, indicating the magnitude of CFTR-mediated chloride transport after basolateral infection CF HAE ALI, as described for (B). CFTR currents generated from primary non-CF HAE (n=14) are provided for comparison. Data represent the mean (±SEM) for n=3 independent Millicell inserts.

We addressed this question by constructing a 5.036-kb AV2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) vector in which the CFTR expression cassette was expanded by the addition of a 3×HA epitope tag (99 nucleotides) in the region encoding the fourth extracellular loop (ECL4) of ferret CFTR (previous studies had revealed that this insertion has no impact on chloride channel function51,52). This vector allowed us to interrogate how size of the genome influences CFTR functionality in the absence of changes to transcription of the transgene. Two rAAV2 vectors were produced [AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR and AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR(HA); Fig. 3A], and their ability to generate CFTR-mediated chloride currents was evaluated in polarized CF HAE. Vector yields for the two viruses were nearly equivalent [AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR, ∼5×109 DRP/μl; and AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR(HA), ∼3×109 DRP/μl]. Polarized CF HAE were cultured at an ALI and infected at the relatively high multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼105 DRP/cell (1011 DRP of each rAAV2 vector per insert). Ten days after infection, the level of CFTR expression was determined by measuring short circuit current (Isc), as previously described.25,53 Figure 3B shows a typical Isc trace after infection of CF HAE with AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR or AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR(HA). Amiloride and DIDS were first applied to block non-CFTR chloride channels and ENaC-mediated sodium currents, and then cAMP agonists (IBMX and forskolin) were used to induce CFTR activity. The changes in Isc after the addition of IBMX and forskolin (ΔIscIMBX&Forsk) and the subsequent addition of the CFTR inhibitor GlyH-101 (ΔIscGlyH) were used to evaluate the function of CFTR. Our results clearly demonstrated that functional complementation of CFTR activity in CF HAE is greater after infection with AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR than with AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) (Fig. 3B). The mean ΔIscIBMX&Forsk and ΔIscGlyH values from these experiments are summarized in Fig. 3C. CFTR-mediated cAMP-inducible Cl– currents produced by AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) were only 3.6% of those in non-CF HAE ALI cultures, but still above background levels (p<0.01). By contrast, infection with AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR produced 10-fold greater cAMP-inducible Cl– currents than AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) and achieved ∼30% CFTR activity of non-CF HAE ALI cultures. These results demonstrate that the cutoff for retaining CFTR function is narrow when producing oversized rAAV genomes, and that vector functionality does not depend only on the efficiency of packaging DRPs. Furthermore, these studies suggest that incorporation of the 100-nucleotide F5 enhancer into AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR, with a total genome size of 5.04 kb, would likely have a significant negative impact on function of the genome.

Effective packaging of a functional ferret CFTR minigene into rAAV

We next explored the possibility of using a shortened ferret CFTR minigene to further reduce the genome size of an rAAV-CFTR vector, and to allow for incorporation of the F5 enhancer. A human CFTR minigene (CFTRΔR) with a 156-bp partial deletion within the R domain (encoding amino acids 708–759) has been reported to retain most of the chloride channel activity of the full-length protein.31,32 We created an fCFTRΔR minigene by deleting the 159-bp homologous sequence encoding amino acids 708–760 at the corresponding position of the human protein, and produced two additional vectors: AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR (4.778 kb) and AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR(HA) (4.877 kb). This pair of vectors allowed us to examine not only the function of the fCFTR minigene in CF HAE ALI cultures, but also the impact of the HA tag insertion in the fCFTR gene. Analysis of ΔIscIBMX&Forsk and ΔIscGlyH responses for these two viruses demonstrated that both AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR and AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) produced substantial CFTR-mediated Cl– currents after infection of the CF HAE ALI cultures (Fig. 3C). However, the HA-tagged form produced ∼20% less Cl– current than AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR. This finding is consistent with rAAV vectors of 4.88 kb having only ∼25% of the functional activity of vectors at 4.68 kb.26 Alternatively, the HA tag may itself influence CFTR function in the context of the R-domain deletion, although in the context of full-length CFTR this ECL4 HA tag has no impact on Cl– channel function.51,52 Despite the larger genome size of AV2/2.tg83-fCFTR (4.9437 kb), this vector produced ∼30% more CFTR-mediated current than its shorter counterpart AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR (4.778 kb) (Fig. 3C). This reduction in Cl– channel activity of fCFTRΔR is similar to that reported for hCFTRΔR.31 However, given the potential for reduced functionality of larger vector genomes, the impact of the R-domain deletion on the function of the ferret CFTR protein is likely greater than that for human CFTR.

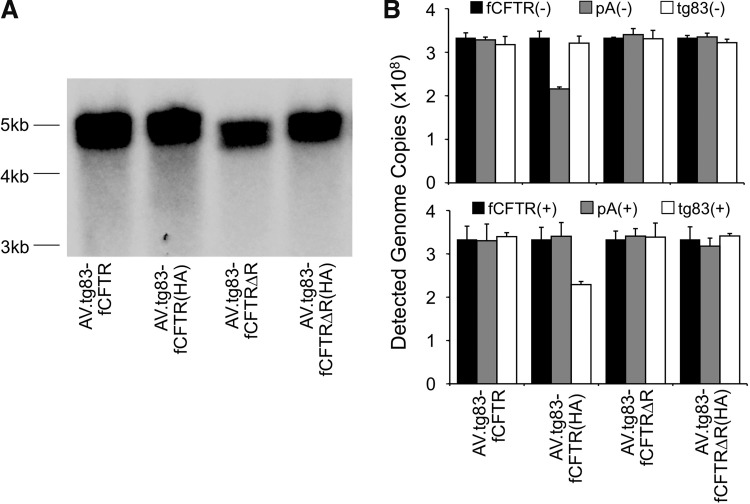

To establish the impact of genome length on packaging of the rAAV vectors tested, we examined integrity of the viral genome, using alkaline-denatured agarose gel electrophoresis followed by Southern blotting (Fig. 4A). This analysis revealed that the smallest vector genome (i.e. that of AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR, 4.778 kb) could be distinguished from the other three viruses on the basis of its faster migration through the gel [AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR is 99 nucleotides shorter than the AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR(HA) vector]. However, AV2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) (5.036 kb), AV2.tg83-fCFTR (4.937 kb), and AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR(HA) (4.887 kb) could not be distinguished from one another on the basis of this analysis. Given that it should be possible to visualize differences of both 149 nucleotides [AV2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) vs. AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR(HA)] and 99 nucleotides [AV2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) vs. AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR(HA), and AV2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) vs. AV2.tg83-fCFTR], we interpret these findings as support for the notion that viral genomes larger than that of AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR(HA) (4.887 kb) tend to incur deletions that compromise CFTR transgene expression.

FIG. 4.

Integrity of the viral genome as determined by denaturing gel electrophoresis and slot-blot analysis. (A) Viral DNA was extracted from 109 DRP of the indicated AAV-CFTR vectors, resolved on a 0.9% alkaline agarose gel, and transferred to a Nylon membrane. Southern blotting was performed with a 32P-labeled CFTR probe to visualize the viral DNA. (B) To assess potential deletion that may have occurred at the termini of plus- and minus-strand viral genomes, 3.33×108 DRP of each virus (titer determined by TaqMan PCR with probe–primer set against fCFTR cDNA) was loaded in triplicate onto a Bio-Dot SF Module (Bio-Rad) fitted with a Nylon membrane. Three-fold serial dilutions of proviral plasmid (3×109 to 3.7×107 copies) were also loaded to generate the standard curves for quantitation. The blots were probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides against the tg83 promoter, CFTR cDNA, or poly(A). (–) and (+) represent the probes hybridizing to the minus and plus strands of the single-stranded rAAV genome. Hybridization was first conducted with the set of probes that hybridize to the minus strand, and then reprobed with the set of oligonucleotides that hybridize to the plus strand. The number of viral genome copies detected by each probe was determined (mean±SEM, n=3) on the basis of measurement of signal density, using NIH ImageJ and comparison with standard curves.

The notion that deletion occurs in the context of longer genomes was further supported by the hybridization of viral genomes with two sets of plus- and minus-strand oligonucleotide probes at the center of CFTR cDNA, the tg83 promoter, and synthetic poly(A) sequences (Fig. 4B). Results from this analysis demonstrated that viral DNA from the largest AV2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) vector incurred deletions at the 5′ ends of both plus- and minus-strand genomes. By contrast, the 3′ end of plus- and minus-strand AV2.tg83-fCFTR(HA) genomes remained intact, consistent with packaging of single-stranded AAV genomes from the 3′ to 5′ direction. The fact that the strength of hybridization at the tg83 promoter (for the plus strand), and the poly(A) sequence (for the minus strand), was lower than that of hybridization to the fCFTR cDNA suggested that these deletions were not restricted to the 5′ ITR region (i.e., that the damage extended into the CFTR expression cassette). Such deletions were not observed in the second longest vector, AV2.tg83-fCFTR; therefore, the CFTR expression cassette in this vector most likely still remains intact, although partial deletions in the 5′ ITR region likely occur as suggested from the viral DNA migration on denatured agarose gels. Although deletions in the ITR regions may not directly influence expression of the CFTR transgene, they may impact the stability of viral genomes and thus indirectly influence CFTR expression. Previous single-molecule sequencing of packaged genomes from a 5.8-kb rAAV proviral transfer plasmid found variable truncations at the 5′ terminus and no deletions within the 3′ ITR.50 Thus, the 3′ ITR of the 4.78- to 5.04-kb rAAV-CFTR vectors most likely remains intact. Although we did not directly evaluate 5′ ITR sequences, we assume that the truncation also removes some or all of the 5′ ITR when oversized genomes are packaged. These results, together with our functional analysis, led us to conclude that the fCFTRΔR cDNA without the HA tag would be best suited for testing the impact of the F5 enhancer on rAAV-mediated CFTR complementation.

The synthetic F5tg83 promoter improves rAAV-mediated CFTR complementation

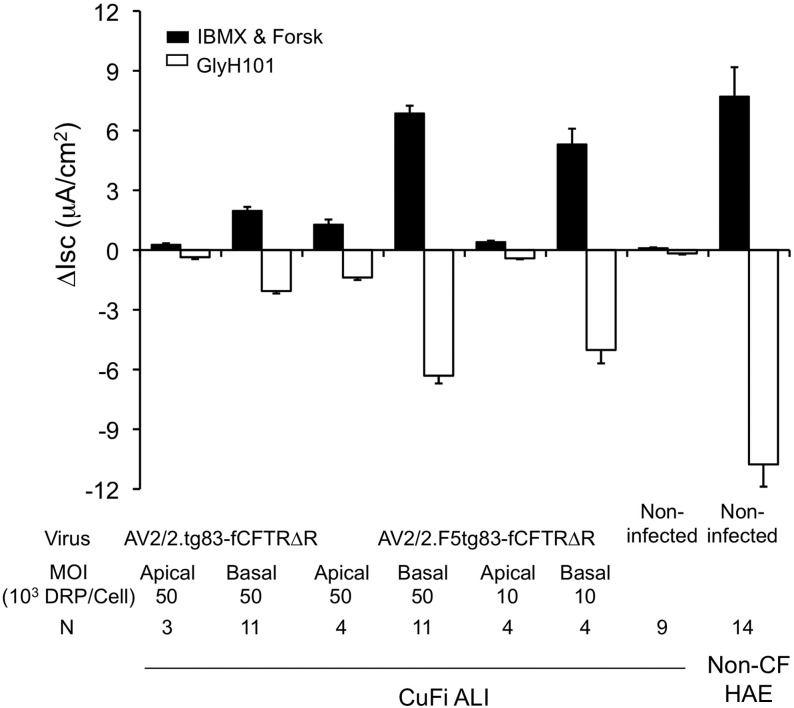

We next generated the pAV2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR proviral plasmid and produced AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR virus with a genome size of 4.87 kb. We compared the efficiency of this virus for complementing function of the CFTR channel after infection of polarized CF HAE with that of the enhancer-less counterpart vector (AV2.tg83-fCFTRΔR). Results from this analysis demonstrated that incorporation of the F5 enhancer greatly improved the CFTR-mediated Cl– currents (Fig. 5). Two weeks after basolateral infection at an MOI of 5×104 DRP/cell, cAMP-induced CFTR-mediated Cl– currents were 3.5-fold greater for AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR than for AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR, and the former was 89% of those observed in non-CF primary HAE. A similar improvement in CFTR function (4.8-fold) was observed with AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR after apical infection, but in this case the efficiency of transduction was significantly lower, as previously reported for this serotype. At the reduced MOI of 1×104 DRP/cell basolaterally, AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR produced 69% of the CFTR current generated by this vector at a 5-fold higher MOI, suggesting that complementation of CFTR function approached saturation in the latter case. Thus, when one compares the effectiveness of AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR (1×104 DRP/cell) and AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR (5×104 DRP/cell) vectors in the context of optimal infection (i.e., basolateral) and nonsaturating conditions, incorporation of the F5 enhancer improved the vector efficacy by 13.5-fold. This level of increase in current is consistent with the increase in expression observed with the analogous luciferase expression vectors (Fig. 2D, 19.6-fold).

FIG. 5.

Effects of the F5 enhancer on CFTR currents generated by CF HAE after infection with rAAV vectors. CF HAE ALI cultures were infected with AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR or AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR, at the indicated MOIs, from the apical or basolateral surface. Proteasome inhibitors were coadministered during the 16-hr infection period. Isc measurements of the infected ALI cultures were conducted 2 weeks postinfection. The mean (±SEM) ΔIsc (IBMX and Forsk) and ΔIsc (GlyH-101) are shown with the number (N) of independent Transwell assays indicated. Mock-infected CF and non-CF HAE cultures are shown for reference.

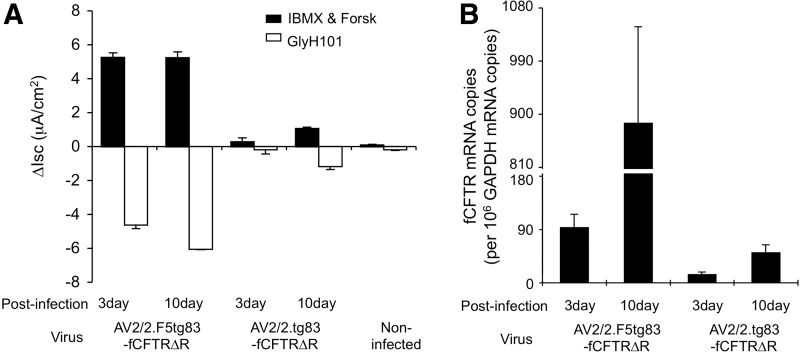

Given the apparent saturation of CFTR currents at the highest MOI (5×104 DRP/cell) after basolateral infection with AV2/2.F5tg83fCFTRΔR, we evaluated the kinetics of CFTR expression at an intermediate MOI (2×104 DRP/cell). Measurements were carried out 3 and 10 days after infection of CF HAE with AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR and AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR. Results from this analysis demonstrated that, in the context of the F5 enhancer, the onset of CFTR-mediated Cl– currents was more rapid than in its absence (Fig. 6A). In fact, CFTR currents were maximal by 3 days after infection with AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR, whereas currents increased 3.6-fold between 3 and 10 days after infection with AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR. To more directly compare transcriptional activity between these vectors, we examined ferret CFTR mRNA by real-time RNA-specific reverse transcriptase PCR (RS-PCR), a method that prevents amplification of vector-derived DNA products and was previously applied in detecting the CFTR mRNA from rAAV-infected cells and tissues.25,49 Analyses of the RS-PCR results, after normalization to ferret GAPDH transcripts, demonstrated 6.4- and 17.1-fold higher levels of fCFTR mRNA after infection with AV2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR versus AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR, at the 3- and 10-day time points, respectively (Fig. 6B). The 10-fold increase in CFTR mRNA observed between 3 and 10 days after infection confirms that CFTR currents were saturated by 3 days postinfection. Thus, at the transcriptional level, incorporation of the F5 enhancer increased CFTR expression 17.1-fold, closely mirroring the results observed with luciferase expression vectors (Fig. 2D, 19.6-fold).

FIG. 6.

Effects of the F5 enhancer on CFTR currents and tg83-directed CFTR transcription after infection with rAAV vectors. CF HAE ALI cultures were infected with AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR or AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR at an MOI of 2×104 DRP/cell from the basolateral surface, in the presence of proteasome inhibitors. (A) Isc was measured in the infected ALI cultures 3 and 10 days postinfection. ΔIsc (IBMX and Forsk) and ΔIsc (GlyH-101) values are presented. (B) The abundance of vector-derived CFTR mRNAs in cultures evaluated in (A), as determined by RS-PCR and normalized to GAPDH transcripts in each sample. Data represent the mean (±SEM) for n=3 independent Transwells in each panel.

Discussion

The rAAV vector has attracted considerable interest with respect to human gene therapy, but its inherently small genome (4.679 kb) is a significant challenge for the delivery of large genes such as CFTR. Although several laboratories, including our own, have attempted to rationally design short enhancers and promoters for use in rAAV vectors, this approach has yet to yield robust expression of CFTR in the airway. In the present study we took an entirely empirical approach, screening synthetic enhancers for their effectiveness in the delivery of reporter gene expression in step-wise fashion—in plasmids, proviral vectors, and viral vectors. Although our main goal was to develop rAAV vectors for delivering CFTR to the airway, a similar approach may prove useful for gene therapy efforts tackling the delivery of other large genes (e.g., factor VIII and dystrophin) that necessitate the use of short promoters.

Production of an oversized rAAV genome is known to lead to random deletions at the 5′ end of the encapsidated single-stranded genomes,50 but the functional integrity of rAAV vector genomes that approach the accepted maximal capacity of rAAV (∼5.0 kb) has not been thoroughly investigated. The current study provides, in the context of CFTR-expressing rAAV vectors, evidence that functionality of the rAAV genome begins to decline well below this 5.0-kb cutoff. Evidence in support of this includes a reduction in CFTR function for 4.877- versus 4.778-kb genomes (Fig. 3C) and the lack of differences in the migration of 4.877- to 5.036-kb single-stranded genomes when visualized on alkaline gels (Fig. 4A). In addition, our largest CFTR vector (5.036 kb) incurred deletion in ∼30% of genomes that extended beyond the 5′ ITR and into the promoter (in the case of the plus strand) or poly(A) region (in the case of the minus strand). This suggests that damage to the CFTR expression cassette may be responsible for the significant impairment of function of CFTR delivered by this vector. Although the oligonucleotide probes used detected deletions in only 30% of genomes for this largest construct, the 90% reduction in CFTR chloride current between 4.937- and 5.036-kb vectors suggests that a much larger percentage of genomes incur functional deletions and that ITR deletions may also impair vector performance.

Our findings seem inconsistent with previous observations of an only 4-fold change in transgene expression between rAAV vectors that are 4.7 and 5.2 kb in size.27 However, in this earlier study the stuffer sequence used to expand the vector was positioned between the expression cassette and the ITR, and deletions of the stuffer sequence would likely have less of an impact on the transcriptional activity of the transgene. The current study of the AAV-CFTR vector instead employed a short synthetic promoter and poly(A) signal, and small deletions within these short transcriptional regulatory elements would be expected to greatly influence gene expression. Because DNase-resistant particle titer is typically used to confirm effective packaging of rAAV genomes, small 5′-end deletions could have a significant impact on functionality of oversized rAAV vectors.

The empirical approach we used to screen synthetic 100-bp enhancers for the ability to improve rAAV-mediated transgene expression in the airway yielded several important observations: (1) Enhancer activity differed significantly by cell lines and also the state of cell differentiation; (2) enhancer activity was influenced by the AAV ITRs and might also be influenced by the sequence of the gene of interest (in this study, the 3′ half of the ferret CFTR cDNA coding region); (3) enhancer activity in the case of rAAV infection was generally similar to that in the context of proviral vector, although with subtle differences; and (4) infection of human and ferret airways with viral vectors revealed some differences in enhancer function (most notably for AV2/2.F1tg83luc; Fig. 2D and E). These results indicate that although transfection with proviral plasmid is suitable for initial screens of synthetic enhancers, performing such a screen in unpolarized primary airway cultures may not produce the same patterns of gene expression observed after AAV infection of polarized airway cultures.

Through this screen, we identified a 100-bp synthetic enhancer (F5) that significantly improves the transcriptional activity of an 83-bp synthetic promoter (tg83), in polarized cultures of both primary human and ferret airway epithelial cells, as well as in ferret lung and trachea in vivo. The ferret CFTR minigene lacking a 53-amino acid portion of the R domain (fCFTRΔR) retained ∼70% of wild-type fCFTR function, similar to the 80% function retained by a previously reported, analogous hCFTRΔR construct.31 Nevertheless, this drawback was greatly compensated by the increased transgene expression from AV2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR, as the use of the shortened minigene spares a 150-bp space to allow for the incorporation of the F5 enhancer. In the context of an rAAV vector, the F5 enhancer significantly improved tg83-driven CFTR mRNA expression (17.1-fold) 10 days postinfection of CF HAE relative to the AV2/2.tg83-fCFTRΔR vector, which lacks this enhancer. This increase in CFTR mRNA expression from AV2/2.F5tg83-fCFTRΔR correlated well with the 19.6-fold improvement in CFTR-mediated currents made possible by this vector, and resulted in production of ∼89% of the cAMP-mediated Cl– currents observed in non-CF HAE. Of note, we found a ceiling on the level of functional correction that can be achieved with respect to the changes in Isc. In the time course studies, maximal correction of Isc in CF HAE was achieved by 3 days postinfection, with the ∼10-fold increase in CFTR mRNA by 10 days postinfection yielding no improvement in Cl– currents (Fig. 6). These findings provide important insight into evaluating the functionality of rAAV-CFTR vectors: dose responses of the vector are needed for accurate comparison of vector designs. The ceiling on CFTR currents could reflect self-limiting cell biology (e.g., control over the total amount of CFTR on the plasma membrane), or aberrant trafficking of CFTR to the basolateral membrane at higher levels of expression.54

In summary, we have generated an rAAV-CFTR vector that provides high-level expression suitable for use in lung gene therapy studies in the CF ferret model. Moreover, our findings suggest that small synthetic enhancers and promoters may be useful tools for optimizing the design of rAAV vectors for the delivery of large transgenes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (HL108902 to J.F.E. and K08 DK092284 to Z.A.S.) and the University of Iowa Center for Gene Therapy (DK54759), the National Ferret Research and Resource Center on Lung Disease (HL123482), and the Roy J. Carver Chair in Molecular Medicine (to J.F.E.). The authors also gratefully acknowledge Dr. Stephen Elledge (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Brigham and Women's Hospital) for providing the enhancer library.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.O'Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2009;373:1891–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 1989;245:1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science 1989;245:1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welsh MJ. Abnormal regulation of ion channels in cystic fibrosis epithelia. FASEB J 1990;4:2718–2725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ. Cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1992–2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welsh MJ, Tsui LC, Boat TF, et al. Cystic fibrosis. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, eds. (McGraw-Hill, New York: ). 1995; pp. 3799–3876 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumner-Jones SG, Gill DR, Hyde SC. Gene Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease. (Birkhäuser Basel, Basel, Switzerland: ). 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller C, Flotte TR. Gene therapy for cystic fibrosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2008;35:164–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griesenbach U, Alton EW. Gene transfer to the lung: lessons learned from more than 2 decades of CF gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2009;61:128–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griesenbach U, Inoue M, Hasegawa M, et al. Viral vectors for cystic fibrosis gene therapy: what does the future hold? Virus Adapt Treat 2010;2:159–171 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter BJ. Adeno-associated virus vectors in clinical trials. Hum Gene Ther 2005;16:541–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, Asokan A, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus serotypes: vector toolkit for human gene therapy. Mol Ther 2006;14:316–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daya S, Berns KI. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008;21:583–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flotte TR. Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors for cystic fibrosis gene therapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2001;3:497–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aitken ML, Moss RB, Waltz DA, et al. A phase I study of aerosolized administration of tgAAVCF to cystic fibrosis subjects with mild lung disease. Hum Gene Ther 2001;12:1907–1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner JA, Nepomuceno IB, Messner AH, et al. A phase II, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of tgAAVCF using maxillary sinus delivery in patients with cystic fibrosis with antrostomies. Hum Gene Ther 2002;13:1349–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moss RB, Milla C, Colombo J, et al. Repeated aerosolized AAV-CFTR for treatment of cystic fibrosis: a randomized placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Hum Gene Ther 2007;18:726–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, et al. Endosomal processing limits gene transfer to polarized airway epithelia by adeno-associated virus. J Clin Invest 2000;105:1573–1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, et al. Polarity influences the efficiency of recombinant adenoassociated virus infection in differentiated airway epithelia. Hum Gene Ther 1998;9:2761–2776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conrad CK, Allen SS, Afione SA, et al. Safety of single-dose administration of an adeno-associated virus (AAV)-CFTR vector in the primate lung. Gene Ther 1996;3:658–668 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Luo M, Trygg C, et al. Biological differences in rAAV transduction of airway epithelia in humans and in Old World non-human primates. Mol Ther 2007;15:2114–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding W, Zhang L, Yan Z, et al. Intracellular trafficking of adeno-associated viral vectors. Gene Ther 2005;12:873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Z, Zak R, Luxton GW, et al. Ubiquitination of both adeno-associated virus type 2 and 5 capsid proteins affects the transduction efficiency of recombinant vectors. J Virol 2002;76:2043–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Z, Lei-Butters DC, Liu X, et al. Unique biologic properties of recombinant AAV1 transduction in polarized human airway epithelia. J Biol Chem 2006;281:29684–29692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang LN, Karp P, Gerard CJ, et al. Dual therapeutic utility of proteasome modulating agents for pharmaco-gene therapy of the cystic fibrosis airway. Mol Ther 2004;10:990–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong JY, Fan PD, Frizzell RA. Quantitative analysis of the packaging capacity of recombinant adeno-associated virus. Hum Gene Ther 1996;7:2101–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Z, Yang H, Colosi P. Effect of genome size on AAV vector packaging. Mol Ther 2010;18:80–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flotte TR, Afione SA, Solow R, et al. Expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator from a novel adeno-associated virus promoter. J Biol Chem 1993;268:3781–3790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aitken ML, Greene KE, Tonelli MR, et al. Analysis of sequential aliquots of hypertonic saline solution-induced sputum from clinically stable patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest 2003;123:792–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Wang D, Fischer H, et al. Efficient expression of CFTR function with adeno-associated virus vectors that carry shortened cftr genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:10158–10163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostedgaard LS, Zabner J, Vermeer DW, et al. CFTR with a partially deleted R domain corrects the cystic fibrosis chloride transport defect in human airway epithelia in vitro and in mouse nasal mucosa in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:3093–3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostedgaard LS, Meyerholz DK, Vermeer DW, et al. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator with a shortened R domain rescues the intestinal phenotype of CFTR–/– mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:2921–2926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostedgaard LS, Rokhlina T, Karp PH, et al. A shortened adeno-associated virus expression cassette for CFTR gene transfer to cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:2952–2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Zhang L, Johnson JS, et al. Generation of novel aav variants by directed evolution for improved CFTR delivery to human ciliated airway epithelium. Mol Ther 2009;17:2067–2077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun X, Yan Z, Yi Y, et al. Adeno-associated virus-targeted disruption of the CFTR gene in cloned ferrets. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1578–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun X, Sui H, Fisher JT, et al. Disease phenotype of a ferret CFTR-knockout model of cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2010;120:3149–3160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivier AK, Yi Y, Sun X, et al. Abnormal endocrine pancreas function at birth in cystic fibrosis ferrets. J Clin Invest 2012;122:3755–3768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun X, Olivier AK, Liang B, et al. Lung phenotype of juvenile and adult cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-knockout ferrets. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014;50:502–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun X, Olivier AK, Yi Y, et al. Gastrointestinal pathology in juvenile and adult CFTR-knockout ferrets. Am J Pathol 2014;184:1309–1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan Z, Sun X, Evans IA, et al. Postentry processing of recombinant adeno-associated virus type 1 and transduction of the ferret lung are altered by a factor in airway secretions. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:786–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlabach MR, Hu JK, Li M, et al. Synthetic design of strong promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010:107:2538–2543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan Z, Zak R, Zhang Y, et al. Distinct classes of proteasome-modulating agents cooperatively augment recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2 and type 5-mediated transduction from the apical surfaces of human airway epithelia. J Virol 2004;78:2863–2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding W, Zhang LN, Yeaman C, et al. rAAV2 traffics through both the late and the recycling endosomes in a dose-dependent fashion. Mol Ther 2006;13:671–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X, Luo M, Guo C, et al. Comparative biology of rAAV transduction in ferret, pig and human airway epithelia. Gene Ther 2007;14:1543–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karp PH, Moninger TO, Weber SP, et al. An in vitro model of differentiated human airway epithelia: methods for establishing primary cultures. Methods Mol Biol 2002;188:115–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zabner J, Karp P, Seiler M, et al. Development of cystic fibrosis and noncystic fibrosis airway cell lines. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2003;284:L844–L854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan Z, Keiser NW, Song Y, et al. A novel chimeric adenoassociated virus 2/human bocavirus 1 parvovirus vector efficiently transduces human airway epithelia. Mol Ther 2013;21:2181–2194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu X, Luo M, Zhang L, et al. Bioelectric properties of chloride channels in human, pig, ferret, and mouse airway epithelia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;36:313–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerard CJ, Dell'aringa J, Hale KA, et al. A sensitive, real-time, RNA-specific PCR method for the detection of recombinant AAV-CFTR vector expression. Gene Ther 2003;10:1744–1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapranov P, Chen L, Dederich D, et al. Native molecular state of adeno-associated viral vectors revealed by single-molecule sequencing. Hum Gene Ther 2012;23:46–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glozman R, Okiyoneda T, Mulvihill CM, et al. N-Glycans are direct determinants of CFTR folding and stability in secretory and endocytic membrane traffic. J Cell Biol 2009;184:847–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher JT, Liu X, Yan Z, et al. Comparative processing and function of human and ferret cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem 2012;287:21673–21685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher JT, Zhang Y, Engelhardt JF. Comparative biology of cystic fibrosis animal models. Methods Mol Biol 2011;742:311–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farmen SL, Karp PH, Ng P, et al. Gene transfer of CFTR to airway epithelia: low levels of expression are sufficient to correct Cl– transport and overexpression can generate basolateral CFTR. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;289:L1123– L1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]