Abstract

We present here a nonviral immunogene therapy trial for canine malignant melanoma, an aggressive disease displaying significant clinical and histopathological overlapping with human melanoma. As a surgery adjuvant approach, it comprised the co-injection of lipoplexes bearing herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase and canine interferon-β genes at the time of surgery, combined with the periodic administration of a subcutaneous genetic vaccine composed of tumor extracts and lipoplexes carrying the genes of human interleukin-2 and human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Following complete surgery (CS), the combined treatment (CT) significantly raised the portion of local disease-free canine patients from 11% to 83% and distant metastases-free (M0) from 44% to 89%, as compared with surgery-only-treated controls (ST). Even after partial surgery (PS), CT better controlled the systemic disease (M0: 82%) than ST (M0: 48%). Moreover, compared with ST, CT caused a significant 7-fold (CS) and 4-fold (PS) rise of overall survival, and >17-fold (CS) and >13-fold (PS) rise of metastasis-free survival. The dramatic increase of PS metastasis-free survival (>1321 days) and CS recurrence- and metastasis-free survival (both >2251 days) demonstrated that CT was shifting a rapidly lethal disease into a chronic one. In conclusion, this surgery adjuvant CT was able of significantly delaying or preventing postsurgical recurrence and distant metastasis, increasing disease-free and overall survival, and maintaining the quality of life. The high number of canine patients involved in CT (301) and the extensive follow-up (>6 years) with minimal or absent toxicity warrant the long-term safety and efficacy of this treatment. This successful clinical outcome justifies attempting a similar scheme for human melanoma.

Introduction

Melanoma represents a highly aggressive malignancy in humans and dogs with a significant overlapping in clinical and histopathological features.1 Spontaneous canine melanoma is a more suitable disease model of human melanoma than traditional rodent systems and can provide very useful preclinical data for treatments' translation to human patients.2 Being highly resistant to standard treatments, the rapid course of the disease invading surrounding normal tissue leads ultimately to regional and distant metastases.2–5

As it was recently reviewed,6 tumor immunogene therapy is a very attractive and rapidly expanding field, as demonstrated by the variety of approaches reported for canine spontaneous melanoma and other malignancies affecting companion animals. Among these approaches, there are two supported by a large number of canine melanoma-treated patients: the xenogeneic vaccine reported by Grosenbaugh et al.,7 and the suicide gene plus autologous/allogeneic vaccine reported by Finocchiaro and Glikin.8 Both treatments, relying on the immune system for systemic disease control, were conceived as surgery adjuvants. Being the human tyrosinase vaccine specific for canine melanoma,7 our approach seemed to be more adaptable, being also effectively applied to canine soft tissue sarcoma9 and osteosarcoma.10

In dogs with melanoma, direct intralesional injections of lipid-complexed plasmid DNA encoding the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSVtk) suicide gene plus ganciclovir (GCV) yielded 44–47% of objective responses.11 However, more than 50% of the tumors as well as their derived cell lines were resistant to this treatment.12 Regardless the chosen approach, the presence of local disease substantially shortened patients' median overall survival.8,11,13 In a different background, local expression of interferon-β induced direct tumor cells cytotoxicity both in vitro14 and in vivo.15,16

In canine soft tissue sarcoma- and osteosarcoma-bearing patients, we successfully applied a treatment that combined the local antiproliferative effects of interferon-β and HSVtk suicide gene therapy with the systemic effects triggered by a subcutaneous vaccine composed of formolized tumor extracts and irradiated xenogeneic cells genetically modified to slowly release human interleukin-2 (hIL2) and human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (hGM-CSF).9,10

The costly production of living cells, associated to their inherent difficulty of being delivered to different animal care centers, precludes the widespread use of this approach to treat veterinary patients that are far from the production facilities. To overcome this situation using simpler components, we replaced the living xenogeneic cells by liploplexes carrying hIL-2 and hGM-CSF genes that were subcutaneously injected with the formolized tumor extracts. Therefore, all the components of the treatment (cationic liposomes, plasmid DNA, and tumor extracts) were suitably formulated for storage and delivery.

We evaluated the effects of an equivalent genetic vaccine as part of our combined treatment (CT) in an aggressive murine melanoma setting.17 Mimicking the surgery adjuvant treatment performed in dogs, we determined the relative contribution of surgery, local suicide gene therapy, and subcutaneous genetic vaccine (composed of B16-F10 cell extracts and lipoplexes carrying human IL-2 and murine GM-CSF genes). We found that, after surgical removal of the tumor, suicide gene plus genetic vaccine CT elicited a powerful antitumor effect evidenced by a better control of recurrence (delay or complete abrogation) and the induction of a potent local and systemic immune response (highlighted by PET scan imaging, the high rate of tumors pseudo-encapsulation, and thymus enlargement). Then, as we had also demonstrated in a previous canine melanoma trial,11 the CT was considerably more effective than the separate monotherapies.

In this context, we proposed a controlled trial to test the effects of the combination of local suicide gene therapy plus cIFNβ together with a systemic anticancer vaccine in canine spontaneous melanoma patients. Immediately after the excision of the tumor, the surgical margin of the cavity was treated with nonviral HSVtk/GCV suicide system plus interferon-β gene therapy. Simultaneously, the patients started to be periodically injected with subcutaneous vaccines composed of autologous or allogeneic formolized tumor cells and lipoplexes carrying hIL-2 and hGM-CSF genes. After 6 years of follow-up and about 300 treated patients, we demonstrated that this combination of local and systemic gene therapy as adjuvant of surgery not only prevented recurrence and metastases, but also significantly improved disease-free and overall survival while maintaining the quality of life.

Materials and Methods

Cell cultures

Cultured cells derived from surgically removed canine melanomas were obtained by enzymatic digestion of tumor fragments and cultured as monolayers and multicellular spheroids as previously described.12

Plasmids

The same psCMV plasmid backbone was used as carrier of all the genes. Escherichia coli β-galactosidase (βgal: psCMVβ), herpes simplex thymidine kinase (psCMVtk), canine interferon-β (psCMVcIFNβ), human interleukin-2 (psCMVhIL2), and hGM-CSF (psCMVhGM-CSF) genes were subcloned, amplified, purified, and diluted to a final concentration of 2.0 mg/ml in sterile PBS as described.8,14

Liposomes preparation and in vivo local lipofection

Liposomes for in vitro experiments12 and liposomes for in vivo injection8 were made as previously reported. The latest ones were composed of equimolar amounts of 1,2-dimyristyl oxypropyl-3-dimethyl-hydroxyethylammonium bromide (DMRIE) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidyl ethanolamine (DOPE). Lipoplexes were assembled by mixing liposomes and plasmid DNAs (1:2 v:v) at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, 5 mg GCV/mg DNA was added and the mixture was injected intra- and/or peritumorally into multiple sites at a final volume of 1–4 ml, according to tumor extent.8 Lipoplexes for tumor vaccines were prepared as described below.

Sensitivity to HSVtk and cIFNβ in vitro assays

Both transiently HSVtk- or βgal-expressing cells were seeded on regular plates as monolayers (3.5–7.0×104 cells/ml) or on top of 1.5% solidified agar to form spheroids (2.0×105 cells/ml) 24 hr after lipofection, and incubated with medium containing 1 μg/ml GCV.12 After 5 days in monolayers or 12 days in spheroids, cell viability was determined by the MTS Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) as previously described. In the case of cIFNβ-expressing cells, they were incubated in a GCV-free media as their respective βgal-expressing control cells were.

Tumor vaccines preparation

Surgically removed tumors were processed as previously described.8 Aliquots of 0.05–0.10 ml of insoluble pellets of homogenized tumors were stored at −80°C until used. No microbial cultivable contamination was found in tumor preparations. Analyses for endotoxin presence (≤1 EU/μg protein) were performed using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay. Autologous or allogeneic tumor cells preparation in 0.25 ml was mixed with 0.75 ml of lipoplexes carrying 0.5 mg psCMVhIL2 plus 0.5 mg psCMVhGM-CSF just before subcutaneous injection.

Patients

Dogs free of severe underlying systemic illnesses entered into the study after a confirmed histopathological diagnostic of melanoma. Tumors were staged according to WHO as previously described.8 Neither chemotherapy nor any other potentially antitumor or immunosuppressive medication was administered to dogs during the study. Standard antibiotics and nonsteroid anti-inflammatory and/or analgesic medication were used when needed. All dogs' owners signed the corresponding written informed consent for this experimental treatment. Surgery procedures and clinical follow-up were performed by qualified attending veterinary professionals, following of the laws and regulations of our country (Argentina). The Academic and Research Committee of the Institute of Oncology (University of Buenos Aires, Argentina) evaluated and approved both scientific and ethics issues related to the veterinary clinical trial.

Study design and treatment

Thirty-two Argentinean veterinary care centers recruited patients and took part in this open-label controlled study. While some owners decided to continue only with palliative care, other ones chose not to follow the intensive gene therapy mostly because of coordination reasons (frequent transportation of the patient). Following the decision of patients' owners, participants were allocated into one of the two main arms designed as surgery plus CT (arm CT) and only surgery treatment (arm ST). At the time of surgery, patients were reassigned taking into account whether they were subjected to complete (arms CS-CT and CS-ST) or partial (arms PS-CT and PS-ST) surgery.

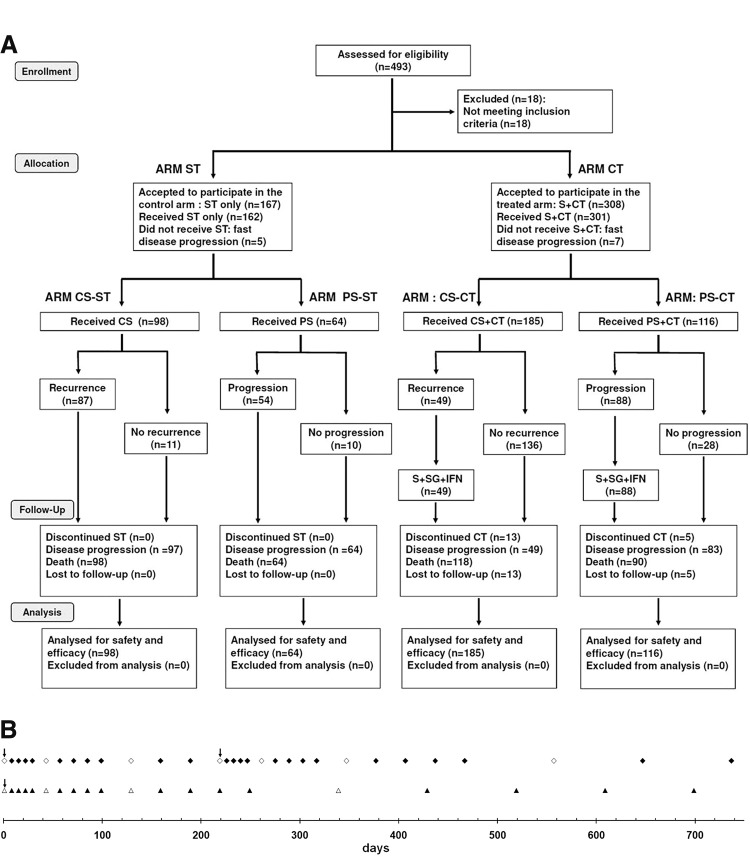

Figure 1A displays the general scheme of the treatment as a CONSORT chart.18 Patients getting the CT (n=301) were subjected to partial (PS, n=116) or complete surgery (removal of all detectable tumor burden followed by confirmation of clean surgical margins in the histopathological report; CS, n=185). The surgical margin of the hollow produced by tumor excision was injected with canine interferon-β (cIFNβ) and suicide genes carrying lipoplexes (1–4 mg DNA of each) co-delivered with GCV (5–20 mg), according to tumor size (about 0.1 mg DNA/cm2 of surgical margin), uniformly spread at multiple locations in the surrounding areas and/or in the remaining tumor tissue. Starting at surgery, patients were treated once a week for 5 weeks with a subcutaneous vaccine composed of autologous (n=157) or allogeneic (n=126) formolized tumor cell extracts (containing about 0.05–0.10 ml of insoluble pellet) and lipoplexes carrying the genes of hIL-2 and hGM-CSF (0.5 mg DNA of each cytokine). After that, patients received subcutaneous vaccine with decreasing frequency: 5 times (5 ×) every other week, 5×monthly, 5×every 3 months, and lastly every 6 months until relapse or death (Fig. 1B). Surgery-only-treated control patients (ST, n=162) passed through complete (CS, n=98) or partial (PS, n=64) surgery without getting further antitumor treatment.

FIG. 1.

Disposition of patients in a CONSORT diagram (A) and treatment time table (B). Starting the day of the surgery (↓), periodic injections of subcutaneous vaccine were applied (▲,△). A new higher interval between inoculations was indicated with the open symbol (◊,△). The sequence of subcutaneous vaccine application reinitiated when a subsequent surgery because of local recurrence was performed (♦,◊). CS, complete surgery; CT, combined treatment; PS, partial surgery; S, surgery; ST, only surgery treatment.

At local recurrence (n=87) or local disease progression (n=91), CT patients were subjected to a second and eventually a third CS or PS (surgery interventions were spaced at least 3 months). Tumor beds were re-injected with cIFNβ and suicide genes carrying lipoplexes co-delivered with GCV as described above. They also restarted the subcutaneous vaccine schedule. The follow-up lasted until the patients' death. For the sake of simplicity, local relapse was considered as recurrence in the same place, invasion of surrounding tissue, and/or regional metastasis (including very proximal lymph nodes).

Periodic clinical evaluations were performed as previously described.8 Patients subjected to a second and eventually a third CS or PS surgery interventions also restarted the (1) periodic clinical evaluations every treatment day and (2) thoracic radiographies and abdominal echographies every month.

Statistical study of survival data was made by Kaplan–Meier analysis where curves were compared by log-rank test, while response data were analyzed by two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

Results and Discussion

Patients' demographics

A CONSORT chart of the trial18 is shown in Fig. 1A and a thorough description of the treatment scheme appears in the Materials and Methods section.

The patients' median age was between 10 and 11 years (Table 1), being the CS-ST group slightly but significantly older than the treated CS-CT group. These differences were because of the slight difference between the male CS-ST subgroup and the corresponding CS-CT one.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics at Study Entry

| Treatment | Surgery treatment (ST, 162) | Combined treatment (CT, 301) | ST vs. CTa; p < | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter (n) | CS-ST (98) | PS-ST (64) | CS-CT (185) | PS-CT (116) | CS | PS |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Median (range) | 11 (1–18) | 11 (1–17) NS vs. CS | 10 (2–18) | 11 (3–16) p<0.04 vs. CS | 0.007 | NS |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (M), CS: n=133 PS: n=94 |

11 (1–18) (n=53) |

11 (1–17) (n=33) NS vs. CS |

10 (2–16) (n=80) |

11 (3–15) (n=61) p<0.02 vs. CS |

0.05 | NS |

| Female (F) CS: n=150 PS: n=86 |

12 (7–17) (n=45) NS M vs. F |

11.5 (6–17) (n=31) NS vs. CS NS M vs. F |

11 (2–18) (n=105) NS M vs. F |

11.5 (3–16) (n=55) NS vs. CS NS M vs. F |

0.05 | NS |

| Breed | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ST vs. CTb; p < | |

| Cocker spaniel | 8 (8.2) | 4 (6.3) | 30 (16.2) | 11 (9.5) | NS | |

| Doberman pinscher | 4 (4.1) | 3 (4.7) | 4 (2.2) | 3 (2.6) | NS | |

| German shepherd | 11 (11.2) | 5 (7.8) | 10 (5.4) | 9 (7.8) | NS | |

| Golden retriever | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.6) | 9 (4.9) | 5 (4.3) | NS | |

| Labrador retriever | 3 (3.1) | 1 (1.6) | 11 (5.9) | 7 (6.0) | NS | |

| Mixed breed | 28 (28.6) | 25 (39.1) | 51 (27.6) | 47 (40.5) | NS | |

| Other breeds | 19 (19.4) | 8 (12.5) | 43 (23.2) | 24 (20.7) | NS | |

| Pekingese | 11 (11.2) | 4 (6.3) | 5 (2.7) | 3 (2.6) | NS | |

| Rottweiler | 3 (3.1) | 2 (3.1) | 14 (7.6) | 4 (3.4) | NS | |

| Schnauzer | 4 (4.1) | 2 (3.1) | 8 (4.3) | 3 (2.6) | NS | |

| 1ry tumor location | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ST vs. CTb; p < | |

| Oral | 80 (81.6) | 57 (89.1) | 161 (87.0) | 102 (87.9) | NS | |

| Digital | 13 (13.3) | 6 (9.4) | 18 (9.7) | 11 (9.5) | NS | |

| Ocular | 2 (2.0) | — | 3 (1.6) | — | NS | |

| Other | 3 (3.1) | 1 (1.6) | 3 (1.6) | 3 (2.6) | NS | |

| Stage | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ST vs. CTb; p< | |

| I–II | 41 (41.8) | 17 (26.6) | 75 (40.5) | 29 (25.0) | NS | |

| III | 51 (52.0) | 41 (64.1) | 99 (53.5) | 75 (64.7) | NS | |

| IV | 6 (6.1) | 7 (10.9) | 11 (6.0) | 12 (10.3) | NS | |

| Metastases location | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ST vs. CTb; p < | |

| Lung | 5 (5.1) | 5 (7.8) | 8 (4.3) | 10 (8.6) | NS | |

| Liver | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.7) | NS | |

| Spleen | — | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.54) | — | NS | |

CS, complete surgery; CT, combined treatment; NS, no significant; PS, partial surgery; ST, surgery-only treatment.

Patients were clinically evaluated and treated as described in Materials and Methods. Other 1ry tumor locations: perianal (3), mammary (1), inferior eyelid (1), retro-orbital (3), and footpad (2).

p-values were calculated by log-rank test for Kaplan–Meier analysis.

p-values were calculated by two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

The main breeds present in ST and CT arms were, respectively, cocker spaniel (7% and 14%), German shepherd (10% and 6%), Pekingese (9% and 3%), rottweiler (3% and 6%), Labrador retriever (2% and 6%), schnauzer (4% and 4%), golden retriever (2% and 5%), and Doberman pinscher (4% and 2%). Most of the patients belonged to mixed breeds (33% and 33%) and other diverse breeds (25% and 22%).

Every ST and CT dog (85% and 87% oral, 12% and 10% digital, 1% and 1% ocular, and 2% and 2% other melanomas) was properly staged. Most of ST and CT dogs were at stage III (57% and 58%, primary tumors≥4 cm diameter without metastasis or any size of primary tumor with lymph node metastasis) or stage I–II (36% and 35%, primary tumors<4 cm diameter and negative proximal lymph nodes). In ST or CT groups, nearly 8% of patients had lung metastases when incorporated to the trial. Regarding any possible bias because of the mode of distribution of patients between the two ST and CT arms, Table 1 shows a balanced distribution of different disease stages (see CS-ST vs. CS-CT and PS-ST vs. CS-ST).

Most of melanoma spheroids were sensitive to interferon-β and/or suicide gene transfer

Looking for a higher efficacy of the local treatment for melanoma, we explored the effectiveness of both canine interferon-β (cIFNβ) gene and herpes simplex thymidine kinase/ganciclovir (HSVtk/GCV) suicide gene therapy in melanoma-derived cell lines. Sixteen melanoma cell lines, derived from surgically removed hepatic (Ll) and scapular (Bts) metastasis or from oral (Br, Bk, Btl Cl, Ds, Fk, Kg, Ol, Rka, Rkb, Rd, Sc, Tr) and ocular (Ak) primary tumors, were maintained in culture and characterized as described.12 All of them were able to grow in suspension as multicellular spheroids.

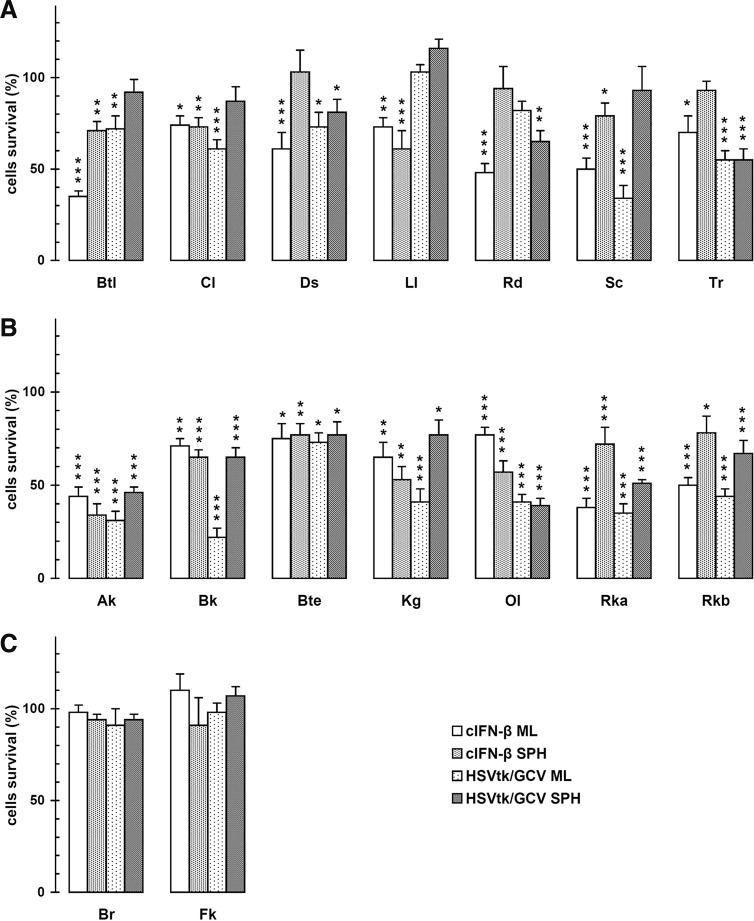

We estimated the suicide gene cytotoxicity at the pharmacologically relevant GCV concentration of 1 μg/ml, similar to an intratumor standard dose of our canine patients.13 Under conditions that more closely resemble the in vivo situation, both cIFNβ and suicide gene killed a substantial amount of the sensitive transgene-expressing cells (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

In vitro sensitivity of canine melanoma cultured spheroids or monolayers to cIFNβ or HSVtk/GCV. Each value was relative to the respective β-gal-expressing condition in the absence (cIFNβ) or presence of 1 mg/ml GCV (HSVtk). Cell lines, whose respective spheroids were insensitive (C) or sensitive to both genes (B) or only to one gene (A), were grouped separately. The results represent means±SEM of four independent experiments performed as described in Materials and Methods. ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

In a previous report we validated the use of multicellular spheroids as highly realistic experimental model for optimizing and predicting the in vivo response of the respective tumors to therapeutic strategies.12 It is noteworthy that, in 16 melanoma cell lines grown as spheroids, while 7 were sensitive to both genetic treatments (Fig. 2B), other 7 cell lines were sensitive to only one of the treatments (Fig. 2A) and only 2 cell lines were insensitive to both treatments (Fig. 2C). Then, we can consider 14 of 16 cell lines (87.5%) and also their original tumors, as potentially sensitive to the parallel treatment.

In the absence of a prognostic molecular analysis about the possible response of a given tumor to any of the two gene transfer approaches at the time of the surgery, the parallel application of both local treatments was considered the best choice.

The CT controlled the local disease

In a previous controlled study with 9 years of follow-up, we demonstrated that the treatment of the surgical margins of the cavity after tumor removal with suicide gene plus GCV could delay or prevent postsurgical recurrence in CS-treated patients.8 In addition, based on the encouraging data obtained in canine spontaneous sarcoma and osteosarcoma patients,9,10 in the present trial we strengthened this new suicide gene-generated margin with the cIFNβ gene. In this way, if tumor cells disseminated in adjacent tissues return to this postsurgical injured immunostimulatory microenvironment, this could destroy them and/or revert their “tumorigenic” phenotype.19,20

When complete tumor resection (CS) was feasible, CT diminished local relapse to about one-third of the proportion found for surgery controls (Table 2). On the other hand, 39% of patients belonging to CT arm remained with local disease because of partial surgery: In this situation, the parallel local application of both cIFNβ and suicide genetic treatments could duplicate the chances of getting tumor response (Fig. 2). In addition, consistently with our previous results on murine melanoma,17 a continuous and sustained local expression of both cIFNβ and suicide genes, by killing cells in an “immunogenic style,” could serve to enhance the immune response.8,21 This was supported by the significant delay in local tumor progression of PS-CT patients (120 days) with respect to PS-ST (45 days) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Time to Local Progression

| ST | CT | ST vs. CT | CS vs. PS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (days) | CS-ST (n=98) | PS-ST (n=64) | CS-CT (n=185) | PS-CT (n=116) | (p<) | ST (p<) | CT (p<) |

| Until relapse | 48 (10–378) (n=87, 88.8%) | — | 222 (50–855) (n=49, 26.5%) | — | 0.0001 | ||

| Until progression | — | 45.5 (7–140) (n=54, 84.4%) | — | 120 (27–885) (n=88, 75.9%) | 0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.0004 |

Patients were clinically evaluated and treated as described in Materials and Methods. The time to local progression after first surgery was considered. p-Values were calculated by log-rank test for Kaplan–Meier analysis.

The gene transfer approach allowed a continuous and sustained local expression of cIFNβ and suicide genes for some days. Thus, a single postsurgical application of this new cIFNβ plus suicide gene-generated margin, systemically sustained by the subcutaneous vaccine, was able of delaying (in 26%, from CS-ST 48 days to CS-CT 222 days) or abolishing local relapse in 74% of the CS-CT patients (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Disease Status at the End of the Study and Causes of Death

| ST (n=162) | CT (n=301) | CT vs. ST | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute | CS-ST (n=98) | PS-ST (n=64) | CS-CT (n=185) | PS-CT (n=116) | p < | |

| Patients | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | CS | PS |

| Local disease-free | 11 (11.2) | 0 | 154 (83.2) | 0 | 4.8×10−16 | — |

| Disease-free | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 136 (73.5) | 0 | 1.5×10−15 | — |

| Metastasis-free: M0 | 43 (43.9) | 31 (48.4) | 165 (89.2) | 95 (81.9) | 1.8×10−15 | 6.5×10−6 |

| Bearing metastasis: M1 | 55 (56.1) | 33 (51.6) | 20 (10.8) | 21 (18.1) | ||

| M1 | ||||||

| M0-1 | 49 (50.0) | 26 (40.6) | 9 (4.9) | 9 (7.8) | 0.00018 | 0.00968 |

| M1-1 | 6 (6.1) | 7 (10.9) | 11 (6.0) | 12 (10.3) | ||

| Alive | 0 | 0 | 54 (29.2) | 21 (18.1) | — | — |

| Dropped out treatment | 0 | 0 | 13 (7.0) | 5 (4.3) | — | — |

| Death | 98 (100) | 64 (100) | 118 (63.8) | 90 (77.6) | — | — |

| Cause of death | CS-ST (n=98) | PS-ST (n=64) | CS-CT (n=118) | PS-CT (n=90) | p < | |

| Patients | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | CS | PS |

| Local disease (LD) | 42 (42.9) | 31 (48.4) | 31 (26.3) | 62 (68.9) | 0.01384 | 0.01250 |

| Metastases (M) | 55 (56.1) | 33 (51.6) | 18 (15.3) | 21 (23.3) | 2.4×10−10 | 0.00054 |

| Disease (LD+M) | 97 (99.0) | 64 (100) | 49 (41.6) | 83 (92.2) | 6.1×10−16 | 0.04182 |

| Unrelated diseases | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 69 (58.5) | 7 (7.8) | ||

CR, complete response; disease-free patients, dead or alive patients without any evidence of disease at the end of the study; local disease-free patients, patients that did not display postsurgical relapse at the end of the study after one or more complete (CS) or partial (PS) surgeries; M0, patients free of distant metastasis all along the treatment; M0-1, dogs that developed distant metastasis during the treatment; M1, animals bearing distant metastases at the end of the treatment; M1-1, patients with distant metastases all along the treatment.

Patients were clinically evaluated and treated as described in Materials and Methods. p-Values were calculated by two-tailed Fisher's exact test.

Undoubtedly, an extremely encouraging outcome was the highly significant (p≈10−15; Table 3) proportion of CS-CT patients local disease-free (83%) and disease-free (74%) compared with the respective of CS-ST (11% and 10%).

The CT controlled the systemic disease

In this study, we modified the formulation of the subcutaneous vaccine by using lipoplexes carrying hIL-2 and hGM-SCF genes, instead of engineered xenogeneic cells secreting these cytokines.8 Cationic lipids and plasmid DNA immunostimulatory sequences might raise both local tumor and subcutaneous vaccine immune response.22,23 This genetic vaccine appeared to be as efficient as the former formulation in promoting a strong antitumor immune response. This was supported by the substantial increase in the percentage of metastasis-free CT patients at the end of the study (CS 89% and PS 82%), compared with their respective ST controls (44% and 48%) (Table 3).

It is worth to note that CT augmented 8-fold (CS) and 4.5-fold (PS) the fraction of metastasis-free patients with respect to those bearing distant metastasis (p≈10−15) (Table 3).

The CT shifted the pattern of causes of death

As shown in Table 3, the notable rise of median overall survival (Table 4) of mostly aged dogs (Table 1) turned out in 58% of CS-CT patients dying of unrelated causes without any evidence of melanoma progression (5% of patients dying of a secondary malignancy). The remaining 42% of CS-CT patients died or were humanely euthanized because of disease progression (26% local tumor and 15% metastases). Conversely, deceased patients of the CS-ST group displayed a significantly different pattern, with 99% dying because of melanoma progression (43% local tumor and 56% metastases). In the case of PS, only 8% of the CT-treated patients died of unrelated diseases, whereas none of the ST patients did so. Only 7% of the CS-CT and 4% of the PS-CT-treated patients abandoned the treatment.

Table 4.

Overall and Disease-Free Survival and Survival Until Progression Obtained from Kaplan–Meier Data

| ST (n=162) | CT (n=301) | CS vs. PS (p<) | ST vs. CT (p<) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (days) | CS-ST | PS-ST | CS-CT | PS-CT | ST | CT | CS | PS |

| Overall (any cause) | 101 (11–568) (n=98) | 78 (29–206) (n=64) | 704 (99–2251) (n=185) | 323 (46–1321) (n=116) | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 |

| Overall (to melanoma) | 109 (33–568) (n=98) | 78 (29–206) (n=64) | >2251 (99–2251) (n=185) | 337 (46–1321) (n=116) | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 |

| Disease-free | 62 (8–425) (n=92) | — | >2251 (69–2251) (n=174) | — | — | — | 0.00001 | 0.00001 |

| Recurrence-free | 63 (8–425) (n=98) | — | >2251 (69–2251) (n=185) | — | — | — | 0.00001 | 0.00001 |

| Metastasis-free | 134 (10–568) (n=92) | 100 (22–162) (n=57) | >2251 (120–2251) (n=174) | >1321 (43–1321) (n=104) | NS | NS | 0.00001 | 0.00001 |

Patients were clinically evaluated and treated as described in Materials and Methods. p-Values were calculated by log-rank test for Kaplan–Meier analysis.

It is worth to note that, after more than a 6-year follow-up period, 29% of CS-CT and 18% PS-CT patients are still alive, most of them without any evidence of disease.

The CT significantly prolonged patients' survival

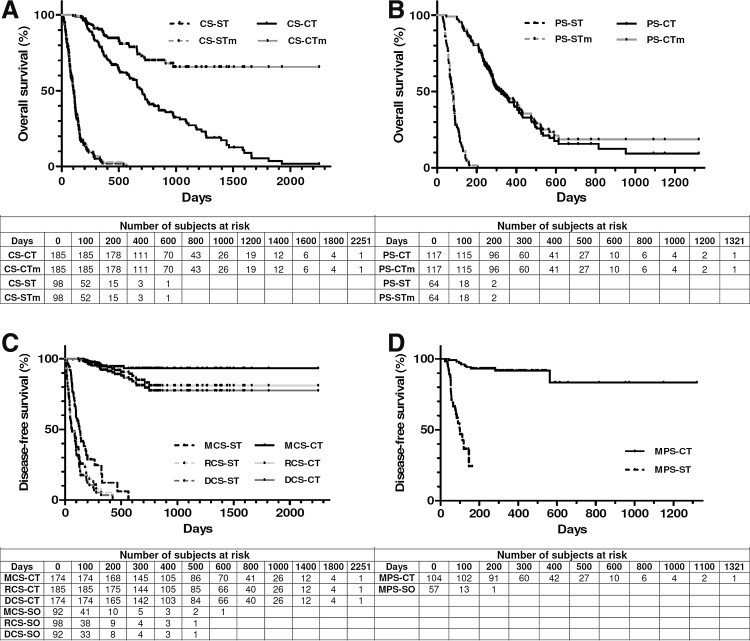

A very encouraging outcome of CT was the remarkable increase of 7-fold (CS) and 4-fold (PS) of overall survival compared with their respective surgery controls (Fig. 3A and B, and Table 4). Even though the slightly lower median ages of the CS-CT group could favor its survival, this cannot explain the high increase of overall survival of this group with respect to the CS-ST group for a very fast-progressing disease like melanoma. In fact, there were no significant survival differences between 1–10 years and 11–18 years of ST controls. Conversely, as expected, in the treated CS-CT group younger patients displayed significantly longer survivals than older patients (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum). When only the death caused by melanoma was considered as a statistical event, this assumption shifted the CS-CT survival curve over 50% exceeding 2251 days (6 years), ruling out the estimation of the median survival. This showed a remarkable increase of CS-CT patients' survival expectation >20-fold compared with CS-ST (Table 4).

FIG. 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall (A, B) and disease-free (C, D) survival. Overall survival because of any cause or melanoma (m) for patients subjected to complete (CS, panel A) or partial (PS, panel B) surgery was censored as described in Table 4. Disease-free survival (DCS-CT, DCS-ST), recurrence-free survival (RCS-CT, RCS-ST), and metastasis-free survival (MCS-CT, MCS-ST; MPS-CT, MPS-ST) for patients subjected to complete (CS, panel C) or partial (PS, panel D) surgery were censored as described in Table 4.

Median survivals of CS-CT patients (even considering those displaying local recurrence) were significantly higher than those of PS-CT patients, and both of them were significantly higher than their respective values for ST patients (Fig. 3 and Table 4). Therefore, CT could significantly delay and/or slow down progression of the recurrent disease. It is worth to note that, in those patients with local disease because of PS or postsurgical relapse, a second and eventually a third surgery intervention followed by tumor bed re-infiltration with cIFNβ and suicide genes appeared as considerably superior to our former strategy.8 With respect to the mentioned previous work, PS-CT patients displayed significantly longer median overall survivals (to any cause: 323 vs. 201 days, p<0.0007; to melanoma: 337 vs. 250 days, p<0.04). CS-CT patients' overall survivals were not significantly different with respect to those of the previous protocol.8

CT considerably raised the disease-, recurrence-, and metastasis-free survival of the CS-CT arm (about 36-, 36-, and 17-fold), and the metastasis-free survival of the PS-CT arm (about 13-fold) with respect to PS-ST arm (Fig. 3C and D, and Table 4). The respective CS and PS metastasis-free survival curves remained over 80% exceeding 2251 days (6 years) and 1321 days (3.6 years), ruling out the calculation of median survivals. Furthermore, the disease- and recurrence-free survival curves remained over 75% exceeding 2251 and 1321 days.

The treatments were innocuous

For clinical adoption, new successful cancer therapies should increase survival times while improving the patients' quality of life. In opposition to other highly toxic therapies, our proposed treatment could contribute to both aims: in addition to the extension of survival, it significantly restored the patients' quality of life to the predisease state.

An estimation of the patients' quality of life was based on the owner's response to a short questionnaire completed before every treatment session. The answers about the different aspects of daily pet's behavior were scored as follows: 1=worse, 2=no change, and 3=better compared with the previous state. During the treatment there was a restoration to the predisease state of activity (78%), alert state (67%), appetite (81%), disposition (89%), and general welfare (76%) in the CT arm. These effects persisted as long as the disease was stable or regressing and they were suppressed after advanced relapse and disease progression.

Repeated intra/peritumoral injections of interferon-β and suicide gene plasmid DNA:DMRIE/DOPE lipoplexes and GCV as well as the subcutaneous administration of formolized tumor cells plus lipoplexes carrying cytokine genes were safe, not allergenic, and could be applied several times. Occasionally, some patients displayed minor adverse side effects that can be classified as grade ≤1 following the VCOG-CTCAE criteria.24 They typically involved induration (14%) at the injection places and a 24 hr diminution of activity (22%), after subcutaneous vaccine application. Recovery from surgery usually took 12–36 hr with swelling and itching (19%) at the surgery place. Gene therapy-treated and -untreated patients displayed a similar postsurgical wound healing and swelling at surrounding areas.

The treatment did not generate significant changes in clinical and hematological parameters, local or systemic toxicity, fever, or organic dysfunction during or after finishing the study.

Conclusions

Based on our previous experience in veterinary clinical trials for canine melanoma,8 we proposed a simpler design of this immunogene therapy approach. This new surgery adjuvant treatment consisted of a single postsurgical application of local cIFNβ plus suicide gene therapy at the time of surgery, complemented with the periodic administration of a subcutaneous genetic vaccine. This vaccine was composed of whole tumor formolized extracts and lipoplexes carrying the genes of hIL-2 and hGM-CSF.

After more than 6 years of follow-up, we conclude that the proposed treatment applied after surgical excision of the tumor showed a high level of safety (even in long-term surviving patients that were periodically treated for many years), and was able of delaying or preventing postsurgical recurrence and metastases. This outcome had a very positive effect on the patients' quality of life and survival rates. Being a high number of patients involved in this veterinary clinical trial (301 in the CT arm), as derived from Fisher's exact test, we achieved a very high level of significance (p≈0) in the comparison of different results at the end of the study between ST and CT arms: (1) general and local disease-free versus disease bearing; (ii) metastasis-free versus metastasis bearing; and (iii) death caused by disease versus unrelated diseases (Table 3).

The dramatic increase of PS metastasis-free survival (>1321 days) and CS recurrence- and metastasis-free survival (both >2251 days) demonstrated that CT was shifting a rapidly lethal disease into a chronic one. As it happened in our previous trial,8 this hypothesis was strongly supported as follows: (1) PS-CT patients displayed significantly longer survivals than PS-ST controls (Table 3), and (2) the number of CS-CT patients that died of melanoma-unrelated causes was so different from that of CS-ST ones, that the possibility of being just a product of hazard was extremely low (p≈10−15; Table 4).

As far as we know, our present and previous clinical trials8 were the largest veterinary cancer gene therapy protocols reported to date. Because of the increased simplicity of the different components involved in the new approach, the effective outcome reported here encourages its next application in veterinary clinical oncology. Additionally, it could provide a preclinical proof of concept and long-term safety data supporting the further translation of similar methodology to clinical trials for human melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our patients and their owners for their cooperation and participation in this study. We thank Graciela Zenobi for technical assistance and all the Doctors of Veterinary Medicine involved in this study for patients' treatment and care, especially Drs. Fernando Calcagno, José L. Suárez, Pablo Meyer, Jorge Blomberg, Soledad Ramírez, and Alejandro Goldman.

This work was supported by grants from ANPCYT/FONCYT (PICT2007-00539 and PICT2012-01738) and CONICET (PIP 112 200801 02920 and PIP 112 201101 00627). L.M.E.F., M.S.V., and G.C.G. are investigators of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, Argentina); C.F., M.L.G.-C., and U.A.R. are research fellows of the CONICET.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or commercial associations.

References

- 1.Simpson RM, Bastian BC, Michael HT, et al. . Sporadic naturally occurring melanoma in dogs as a preclinical model for human melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2014;27:37–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen K, Khanna C. Spontaneous and genetically engineered animal models; use in preclinical cancer drug development. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:858–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos-Vara JA, Beissenherz ME, Miller MA, et al. . Retrospective study of 338 canine oral melanomas with clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical review of 129 cases. Vet Pathol 2000;37:597–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SH, Goldschmidt MH, McManus PM. A comparative review of melanocytic neoplasms. Vet Pathol 2002;39:651–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modiano JF, Breen M, Lana SL, et al. . Naturally occurring translational models for development of cancer gene therapy. Gene Ther Mol Biol 2006;10:31–40 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glikin GC, Finocchiaro LME. Clinical trials of immunogene therapy for spontaneous tumors in companion animals. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:718520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosenbaugh DA, Leard AT, Bergman PJ, et al. . Safety and efficacy of a xenogeneic DNA vaccine encoding for human tyrosinase as adjunctive treatment for oral malignant melanoma in dogs following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Am J Vet Res 2011;72:1631–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finocchiaro LME, Glikin GC. Cytokine-enhanced vaccine and suicide gene therapy as surgery adjuvant treatments for spontaneous canine melanoma: 9 years of follow-up. Cancer Gene Ther 2012;19:852–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finocchiaro LME, Villaverde MS, Gil Cardeza ML, et al. . Cytokine-enhanced vaccine and interferon-β plus suicide gene as combined therapy for spontaneous canine sarcomas. Res Vet Sci 2011;91:230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finocchiaro LME, Spector A, Rossi UA, et al. . The potential of suicide plus immune gene therapy for treating osteosarcoma: the experience on canine veterinary patients. In: Sarcoma: Symptoms, Causes and Treatments. Butler EJ, ed. (Nova Science Publishers, New York, NY: ). 2012; pp.107–122 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finocchiaro LME, Fiszman GL, Karara AL, et al. . Suicide gene and cytokines combined non viral gene therapy for spontaneous canine melanoma. Cancer Gene Ther 2008;15:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gil-Cardeza ML, Villaverde MS, Fiszman GL, et al. . Suicide gene therapy on spontaneous canine melanoma: correlations between in vivo tumors and their derived multicell spheroids in vitro. Gene Ther 2010;17:26–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finocchiaro LME, Glikin GC. Cytokine-enhanced vaccine and suicide gene therapy as surgery adjuvant treatments for spontaneous canine melanoma. Gene Ther 2008;15:267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villaverde MS, Gil-Cardeza ML, Glikin GC, et al. . Interferon-β lipofection I. Increased efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs on human tumor cells derived monolayers and spheroids. Cancer Gene Ther 2012;19:508–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida J, Mizuno M, Wakabayashi T. Interferon-beta gene therapy for cancer: basic research to clinical application. Cancer Sci 2004;95:858–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Streck CJ, Dickson PV, Ng CY, et al. . Antitumor efficacy of AAV-mediated systemic delivery of interferon-beta. Cancer Gene Ther 2006;13:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villaverde MS, Combe K, Duchene AG, et al. . Suicide plus immune gene therapy prevents post-surgical local relapse and increases overall survival in an aggressive mouse melanoma setting. Int Immunopharmacol 2014;22:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. . CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuertes MB, Woo SR, Burnett B, et al. . Type I interferon response and innate immune sensing of cancer. Trends Immunol 2013;34:67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marabelle A, Kohrt H, Caux C, et al. . Intratumoral immunization: a new paradigm for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:1747–1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesnil M, Yamasaki H. Bystander effect in herpes simplex virus-thymidine kinase/ganciclovir cancer gene therapy: role of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Cancer Res 2000;60:3989–3999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roman M, Martin-Orozco E, Goodman JS, et al. . Immunostimulatory DNA sequences function as T helper-1-promoting adjuvants. Nat Med 1997;3:849–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li S, Wilkinson M, Xia X, et al. . Induction of IFN-regulated factors and antitumoral surveillance by transfected placebo plasmid DNA. Mol Ther 2005;11:112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veterinary Co-operative Oncology Group. Veterinary Co-operative Oncology Group—Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (VCOG-CTCAE) following chemotherapy or biological antineoplastic therapy in dogs and cats v1.0. Vet Comp Oncol 2004;2:195–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.