Abstract

Background

Incisional hernia is the most common complication of abdominal surgery leading to reoperation. In the United States, 200,000 incisional hernia repairs are performed annually, often with significant morbidity. Obesity is increasing the risk of laparotomy wound failure.

Methods

We used a validated animal model of incisional hernia formation. We intentionally induced laparotomy wound failure in otherwise normal adult, male Sprague-Dawley rats. Radio-opaque, metal surgical clips served as markers for the use of x-ray images to follow the progress of laparotomy wound failure. We confirmed radiographic findings of the time course for mechanical laparotomy wound failure by necropsy.

Results

Noninvasive radiographic imaging predicts early laparotomy wound failure and incisional hernia formation. We confirmed both transverse and craniocaudad migration of radio-opaque markers at necropsy after 28 d that was uniformly associated with the clinical development of incisional hernias.

Conclusions

Early laparotomy wound failure is a primary mechanism for incisional hernia formation. A noninvasive radiographic method for studying laparotomy wound healing may help design clinical trials to prevent and treat this common general surgical complication.

Keywords: Incisional hernia, Laparotomy wound, Wound healing

1. Introduction

Incisional hernia is the most common complication of abdominal surgery [1,2]. Incisional hernia repair is the most common reason for reoperation in abdominal surgery patients. It is estimated that the annual incidence of incisional ventral hernia is approximately 400,000 in the United States, and at least 200,000 of these patients undergo incisional hernia repair [3]. Primary, autologous tissue reconstructions will fail and reherniate more than 60% of the time [4]. A randomized, controlled human trial found that the application of polypropylene mesh to stabilize the abdominal wall repair significantly reduced recurrence; however, the mesh repair recurrence rate remained high, at 24% over only 3 y [2]. A mesh-based strategy alone also introduces new complications unique to synthetic implants, such as infection and intestinal injury. Studies have reported that the risk of bowel injury or unplanned bowel resection is up to 21% in patients who underwent prior incisional hernia repair with the placement of intraperitoneal synthetic mesh [5,6]. A large, population based cohort study confirmed that even with the introduction of mesh-based repairs, reoperations for recurrent incisional hernia approach 30% [1]. Administrative databases and outcomes studies now report that frequent patient comorbidities including obesity, immunosuppression, pulmonary disease, and malnutrition increase the risk of wound failure and recurrent incisional hernia [7–9]. In obese patients with boy mass indexes > 35, the incidence of laparotomy wound failure and incisional hernia formation is reported as high as 33%, or 2.8 times the rate of normal weight control groups. Trauma and acute care surgeons increasingly perform temporary laparotomy to manage abdominal compartment syndrome, leading to increased risk for mechanical failure of the abdominal wall and incisional hernia formation [3]. A prospective study on midline abdominal wall incisional hernia showed that it is related to the wound closure technique [10]. Compared with inguinal hernia repair, it appears that the surgical complications of ventral laparotomy wound failure and recurrent incisional hernia are more significant, and that the introduction of the mesh repair alone has not solved the problem.

Defining when wound failure occurs is important to understanding the mechanism of hernia formation. Pollock and Evans [11] first observed in a human trial that laparotomy wound gaps of 12 mm as early as Postoperative Day 30 predict a 94% incisional hernia rate over 3 y. Computed tomographic scan studies of abdominal wall repair subsequently confirmed the observation that early laparotomy wound failure is the mechanism for incisional hernia formation [12]. This suggests that the enormous clinical problem of incisional hernia formation fundamentally results from limits to surgical technique, leading to early wound failure; and that primary collagen disease and disorders that impair laparotomy wound organization, leading to delayed incisional hernia formation, have a less significant role [13,14]. The relative contributions of patient comorbidities, genotypic defects in wound healing, and specific surgical technique to this early wound failure have not been established.

For all of these reasons, improved research is needed to understand the mechanism of the most common general surgical complication, and ultimately for the application of therapies to reduce the high incidence of laparotomy wound failure and incisional hernia formation. To improve data collection in human trials of laparotomy wound healing, for example, a valid and noninvasive method for monitoring early laparotomy wound healing in the postoperative period is needed. A simple, safe, widely available, and inexpensive method would be best.

Our hypothesis was that intentional, early laparotomy wound failure in an animal model would result in incisional hernia formation in otherwise normal animals. Technically, we established mechanical failure of the laparotomy wound using metallic markers and radiographic images, much like the human trial referenced above [11]. We confirmed incisional hernia rings grossly and histologically, as previously reported [15–18].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal model of laparotomy wound healing

We acclimated Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 250 g and housed them under standard conditions. Animals were allowed free intake of standard rat chow and water throughout the study. We performed all animal care and operative procedures in accordance with the United States Public Health Service Guide for the Care of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 86-23, revised 1985), and they were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) of the University of Michigan.

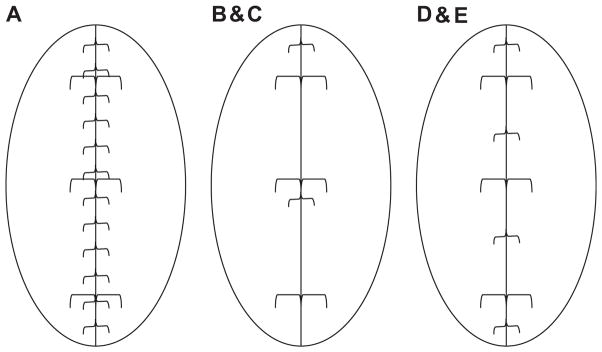

2.2. Laparotomy repair and incisional hernia formation marked with metal clips

Briefly, we raised a 6 × 3-cm ventral full-thickness skin flap through the avascular prefascial plane and made a 5-cm full-thickness laparotomy incision through the linea alba in the musculotendinous layer of the abdominal wall. Figure 1 diagrams the technique of polypropylene suture fascial closure and metallic clip markers. Figure 2 shows gross images of polypropylene laparotomy wound closure and metallic clip markers. We examined laparotomy wounds on Postoperative Day 28. Figure 2A demonstrates placement of the metallic clip markers before laparotomy repair. We used three different techniques for fascial closure for Rats A–E. For Rat A, we repaired the fascia with a running 4-0 polypropylene suture using 0.3-cm suture bites and 0.5-cm progress between stitches (Figs. 1A and 2D) and tied the suture to itself at the end of the wound. This resulted in complete fascial healing without hernia formation. For Rats B and C, we used two interrupted, 5-0 fast-absorbing plain gut sutures for fascial repair, as shown in Figures 1B, 1C, and 2B. The use of rapidly absorbing suture induces early mechanical failure of the laparotomy wound and consistently results in incisional hernia formation [16–18]. For Rats D and E, we placed four 5-0 fast-absorbing plain gut sutures to close the fascia, as shown in Figures 1D, 1E, and 2C. We then returned the skin flap in all rats and sutured them in place with three 4-0 polypropylene stitches and steel skin wound clips. After 30 min of recovery under a heat lamp, we returned the rats to fresh individual cages.

Fig. 1.

Three suture placement models of laparotomy closure and adjacent location of paired metal wound clips along the edges of midline laparotomies. Parts A–E are labels for five rats used in these three models. { =polypropylene suture, or 5-0 fast absorbing plain gut sutures; [ = metal wound clip.

Fig. 2.

Demonstration of metal laparotomy wound clip markers and laparotomy closure techniques in the incisional hernia model. (A) Skin flap is elevated to isolate the laparotomy wound, and metal wound clip markers are initially placed on one side (arrows). (B) Example of laparotomy repaired with two 5-0 fast-absorbing plain gut sutures and placement of paired laparotomy wound metal markers, now one on each side of the incision (Rats 1B and 1C). (C) Laparotomy repair with four 5-0 fast-absorbing plain gut suture stitches (Rats 1D and 1E). (D) Laparotomy repair with continuous running 4-0 permanent suture (Rat 1A).

2.3. Measurement of laparotomy wound gap between paired metal clips

Immediately after the operation and on Postoperative Days 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28, we anesthetized the rats, placed them in a supine position, and took standardized radiographs. We defined the transverse gap between paired metal clips as the separation between the two closest points of paired wound clips and measured it from the radiographic images. We also measured craniocaudad distance between clips on the left side.

2.4. Necropsy measurement of gap between paired metal wound clips and hernia size

To directly measure laparotomy wound gaps and progressive incisional hernia size, we completed necropsies on Postoperative Day 28. We dissected the skin free circumferentially and excised a 5 × 10-cm block of the abdominal wall muscle. We pinned down the muscle on a dissecting board at the four corners with the peritoneal side up. We set a ruler alongside the wound as a calibration reference for every sample and took a standardized digital photograph. We used Software Spot, Windows, Version 4.5 (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., University of New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia) to calculate the separation and hernia size on digital photographs.

3. Results

3.1. Radiographic time course for laparotomy wound separation

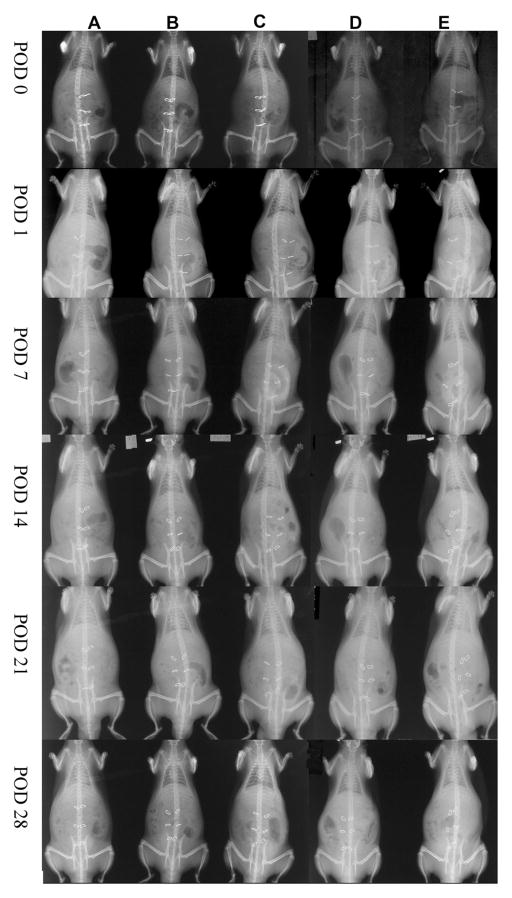

Figure 3 shows the radiographic time course for laparotomy repair and subsequent failure. After placing the metal wound clips and closing the skin, we obtained x-ray images for all five rat models at the indicated time points. The location and separation of paired metal wound clips over time were easily visualized and measured. When the laparotomy was securely closed with a continuous polypropylene suture (the healing, or non-hernia model), the metal clips remained next to each other and did not migrate or form a gap over 28 d (Rat A). When laparotomy repair was intentionally unstable (incisional hernia models), radiographs showed metal clip separation in all animals over 28 d (Rats B and C).

Fig. 3.

Serial radiographs of all groups demonstrating migration of the metal laparotomy wound clip markers. The photographs were taken while the rats were anesthetized and supine. Temporal images from the same rats are arranged in columns A–E. Radiographs taken at the same time are arranged in rows (Postoperative Days 0–28).

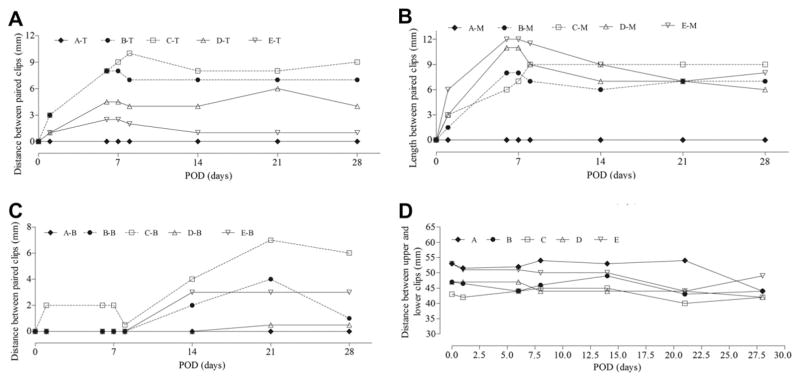

We measured the distance between paired clips on radiographs (Fig. 4). The paired clips placed on the stably repaired abdominal wall of Rat A did not separate during the experimental period. For incisional hernia model Rats B–E, gaps between upper and middle paired clips were evident by Postoperative Day 7. The gaps between lower abdominal wall laparotomy clips were not as evident until Postoperative Day 14. The distance between upper and lower clips (craniocaudad gap), a measure of wound length, was relatively stable.

Fig. 4.

Time curves of transverse separation between paired metal wound clips (laparotomy wound gap) and craniocaudad distance for each rat, A–E. (A) Separation between upper clip pairs (T). (B) Separation between middle clip pairs (M). (C) Separation between lower clip pairs (B). (D) Separation between upper and lower clips on left side. POD = Postoperative Day.

3.2. Metal clips as a marker of laparotomy wound failure and incisional hernia formation

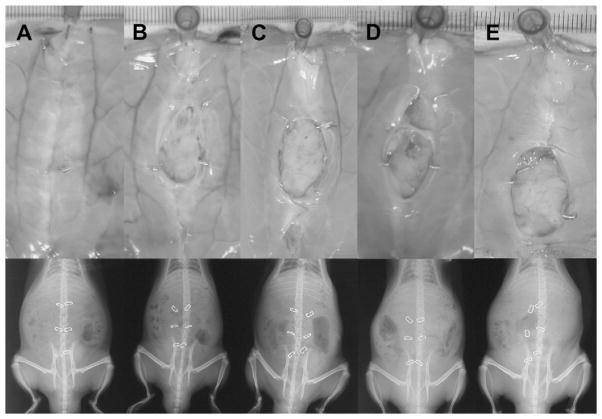

We observed no evidence that the presence of the metal clips interfered with wound healing or contributed to wound infection. As shown in Figure 5 and the top row of Figure 6, the entire incisional line on the Rat A model healed completely without a wound defect. As expected, incisional hernias formed in Rats B–E as a result of intentional mechanical laparotomy wound failure (incisional hernia models). We also measured hernia size (surface area) during necropsy (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Measurement of hernia (or wound defect) size in each rat. We completed necropsies on Postoperative Day 28, collected abdominal walls en bloc, and pinned them down with the peritoneal side facing up. We set a ruler beside the abdominal wall sample as a calibration for subsequent measurements on digital images using Spotsoftware 4.5.3.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the position and migration of metal wound clips on radiographs and on abdominal wall specimens taken en bloc on Postoperative Day 28. We took radiographs of live animals on Postoperative Day 28, and then performed necropsy. We collected rat abdominal wall samples and pinned them down with the peritoneal side facing up. Then, we took digital photographs. Radiographs are arranged below each corresponding rat photograph.

The gap or separation of wound edge markers seen on the radiographs correlated with the size of the hernia measured during necropsy (Figs. 6 and 7). We measured the separation between paired metal clips on radiographs taken immediately before necropsy on Postoperative Day 28. Immediately afterward, we measured metal clip separation directly on abdominal wall samples. As shown in Figure 6, paired clips that separated on radiographic images were adjacent to maturing incisional hernia rings on abdominal wall samples. Importantly, this was true even when there was no gross sign of hernia on Rats B–E on physical exam before death, the clinical scenario of occult fascial dehiscence. Paired clips shown close together on radiographs were embedded close to each other in scar tissue within healed segments of laparotomies (Fig. 6, within white circles). The gaps that developed between paired clips measured on radiographs were consistent with those measured directly during abdominal wall necropsy (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Measurement and comparison of wound edge clip separation from radiographs and abdominal wall samples. Again, we set a ruler beside the abdominal wall sample to calibrate measurements on digital photographs using Spotsoftware 4.5.3. (A) Separation between upper clip pairs (U). (B) Separation between middle clip pairs (M). (C) Separation between lower clip pairs (L). (D) Separation between upper and lower clips on left side.

4. Discussion

We have shown in our model that early laparotomy wound failure in otherwise normal rats results in incisional hernia formation [15–18]. This supports the clinical observation that early mechanical failure of the laparotomy wound may be the primary mechanism of incisional hernia formation [11,12]. If it is true that technical failure with inherent limitations in the way laparotomy wounds are currently repaired is the primary mechanism for this common surgical complication, research efforts should be directed toward improving early acute laparotomy wound healing and wound closure techniques. Human studies are obviously limited in the ability to observe or sample the early laparotomy wound. We propose here a simple, safe, and reliable surrogate for laparotomy wound healing, especially in patients at high risk for incisional hernia formation, such as those who are obese or who develop wound infections. The approach is based on the work of Pollock and Evans [11] and simply calls for marking the laparotomy wound edge with metallic clips easily visualized with a single postoperative radiograph. With controlled variation in the degree of laparotomy wound failure and the ability in an animal model to verify and correlate necropsy samples, we found that radiographic imaging predicts laparotomy wound failure in the early postoperative period. Information such as this improves our understanding of laparotomy wound healing in general, and provides a noninvasive surrogate marker for laparotomy healing in human clinical trials. Computed tomographic scan imaging may be less accurate in measuring transverse laparotomy gaps without metallic markers, and may increase radiation exposure and add significant cost. Ultrasound studies of the abdominal wall and laparotomy incisions are technique-dependent, are likely less detailed for laparotomy wound examination specifically, and may be limited by incisional pain in the early postoperative period.

Early laparotomy wound failure and the loss of normal wound healing architecture may induce the selection of an abnormal population of wound repair fibroblasts, as occurs in chronic wounds [16,18]. This could result in the expression of abnormal structural collagen, which explains the high incidence of recurrent incisional hernias. One mechanism of phenotypic selection of abnormal laparotomy wound repair fibroblasts is the loss of abdominal wall load force signaling as the incision mechanically fails. It is recognized that mechanical load forces stimulate tendon repair fibroblasts and contribute to the organization of remodeling collagen fibers [21]. Wound ischemia also ensues during early acute wound failure, propagating deficient soft tissue repair. It is possible that a subset of incisional hernia patients expresses a genetic defect in extracellular matrix or wound repair function. It is difficult to conclude the existence of a primary genetic mechanism with the fact that most surgical patients have no history of a wound-healing defect and do not express a defect at the primary surgical site (gastrointestinal tract, vascular system, solid organs, etc.). It is possible that early mechanical failure is the major mechanism for incisional hernia formation and that the loss of mechanical load signaling or another acute wound-healing pathway induces defects in repair fibroblast biology. Because the tissue fibroblast is the major source for collagen synthesis and turnover, defects in fibroblast function are an important mechanism for subsequent tissue collagen dysfunction.

Accumulating clinical evidence suggests that most incisional hernias develop after the mechanical disruption of laparotomy wounds during the initial lag phase of the wound healing trajectory. Clinically evident early laparotomy wound failure is a rare event, with reported dehiscence rates of 0.1% [22]. Prior wound-healing literature concluded that incisional hernias were the result of late laparotomy wound failure and scar breakdown [23]. This concept was challenged by clinical studies of incisional hernias that recorded high primary and secondary recurrence rates after short-term follow-up, typically only 2–4 y [2]. Prospective studies find that the true rate of laparotomy wound failure is closer to 11%, and that most of these (94%) form incisional hernias during the first 3 y after abdominal operations [11,12]. The true laparotomy wound failure rate is therefore much greater that what many surgeons believe it to be. By this mechanism, most incisional hernias and recurrent inguinal hernias originate from clinically occult dehiscences. The overlying skin wound heals, concealing the underlying myofascial defect. This mechanism of early mechanical laparotomy wound failure is more consistent with modern acute wound-healing science. There are no other models of acute wound healing suggesting that a successfully healed acute wound goes on to break down and mechanically fail at a later date.

Surgical wound failure most often results from suture pulling through adjacent tissue and not suture fracture or knot slippage [19]. Tissue failure occurs in a metabolically active zone adjacent to the acute wound edge where proteases activated during normal tissue repair result in a loss of native tissue integrity at the point where sutures are placed. The breakdown of the tissue matrix adjacent to the wound appears to be part of the mechanism for mobilizing the cellular elements of tissue repair.

Abdominal wall tendons and fascia are connective tissues placed under intrinsic and extrinsic loads that likely depend on mechanical signals to regulate fibroblast homeostasis. Mechanotransduction pathways have been described in great detail in ligament, tendon, and bone repair [20,24,25]. Mechanical signals are transmitted to the structural cell via integrin receptors, for example, and subsequently affect repair cell metabolism through the modulation of cytoskeleton anchoring proteins. In brief, a load imparted on a soft tissue or bone is transmitted to structural cells through the extracellular matrix via transmembrane integrin receptors located on the cell surface. In one proliferative pathway, subsequent activation of the focal adhesion kinase complex leads to cytoskeletal changes and the further activation of downstream signaling tyrosine kinases such as c-src and the mitogen-activated protein kinase proliferation pathway [20].

The varying mechanical forces exerted across anatomically different laparotomy incisions such as midline versus transverse therefore may affect repair fibroblast activation, provisional matrix assembly, and collagen deposition, and ultimately the temporal recovery of laparotomy wound tensile strength. Surgical experience has long held that transverse abdominal wall incisions oriented parallel to the predominant myofascial fibers regain unwounded tissue strength faster, but a clear benefit on wound outcomes has never been proven [26]. Applicable methods for studying laparotomy wound healing during clinical trials, such as presented in this model, may improve our understanding of the importance of laparotomy wound orientation.

Optimized laparotomy wound healing therefore depends on the normal assimilation of both biological and mechanical signals. Factors that interfere with either or both of these pathways result in delays or defects in the early phases of acute wound healing. From the biological perspective, this most commonly includes infection, ischemia, malnutrition, and pharmacological inhibitors. From the mechanical perspective, this involves the reinforcing cycle of wound failure with a loss in optimal strain loads and a down-regulation of the mechanotransduction pathways normally activated to signal tissue repair. At one extreme, this results from acute wound overload and overt mechanical failure; at the other extreme, it may be due to acute wound underload as the result of a poor suturing technique or the placement of a bridging mesh implant.

There is growing evidence that most incisional hernias result from early laparotomy wound failure. It is likely that the majority of these cases occur because of the mechanical and biological limitations of the current techniques for laparotomy wound closure. Because this is now the most common complication of abdominal surgery, innovations and advances are needed. This study demonstrates the feasibility of a simple and noninvasive but accurate method for studying the mechanics of postoperative laparotomy wound repair. This model may have a role in the design and implementation of clinical trials to improve outcomes in abdominal surgery.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Department of Defense USAMRMC Grant No. 06100002.

References

- 1.Flum DR, Horvath K, Koepsell T. Have outcomes of incisional hernia repair improved with time? A population-based analysis. Ann Surg. 2003;237:129. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, van den Tol MP, et al. A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:392. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franz MG. The biology of hernia formation. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger JW, Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg. 2004;240:578. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141193.08524.e7. discussion 583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray SH, Vick CC, Graham LA, et al. Risk of complications from enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection during elective hernia repair. Arch Surg. 2008;143:582. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halm JA, de Wall LL, Steyerberg EW, et al. Intraperitoneal polypropylene mesh hernia repair complicates subsequent abdominal surgery. World J Surg. 2007;31:423. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0317-9. discussion 430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunne JR, Malone DL, Tracy JK, et al. Abdominal wall hernias: risk factors for infection and resource utilization. J Surg Res. 2003;111:78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finan KR, Vick CC, Kiefe CI, et al. Predictors of wound infection in ventral hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2005;190:676. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, McCarter MD, et al. Effect of body mass index on short-term outcomes after colectomy for cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:53. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruppo M, Mazzalai F, Lorenzetti R, et al. Midline abdominal wall incisional hernia after aortic reconstructive surgery: a prospective study. Surgery. 2012;151:882. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollock AV, Evans M. Early prediction of late incisional hernias. Br J Surg. 1989;76:953. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burger JW, Lange JF, Halm JA, et al. Incisional hernia: early complication of abdominal surgery. World J Surg. 2005;29:1608. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7929-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansen PL, Mertens Pr P, Klinge U, et al. The biology of hernia formation. Surgery. 2004;136:1. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Si Z, Bhardwaj R, Rosch R, et al. Impaired balance of type I and type III procollagen mRNA in cultured fibroblasts of patients with incisional hernia. Surgery. 2002;131:324. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.121376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DuBay DA, Choi W, Urbanchek MG, et al. Incisional herniation induces decreased abdominal wall compliance via oblique muscle atrophy and fibrosis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:140. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251267.11012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuBay DA, Wang X, Adamson B, et al. Progressive fascial wound failure impairs subsequent abdominal wall repairs: a new animal model of incisional hernia formation. Surgery. 2005;137:463. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franz MG, Kuhn MA, Nguyen K, et al. Early biomechanical wound failure: a mechanism for ventral incisional hernia formation. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9:140. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franz MG, Smith PD, Wachtel TL, et al. Fascial incisions heal faster than skin: a new model of abdominal wall repair. Surgery. 2001;129:203. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.110220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson MA. Acute wound failure. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:607. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt C, Pommerenke H, Durr F, et al. Mechanical stressing of integrin receptors induces enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of cytoskeletally anchored proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benjamin M, Hillen B. Mechanical influences on cells, tissues and organs–“mechanical morphogenesis. Eur J Morphol. 2003;41:3. doi: 10.1076/ejom.41.1.3.28102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santora TA, Roslyn JJ. Incisional hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73:557. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peacock J. Fascia and muscle. In: Peacock J, editor. Wound repair. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1984. p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skutek M, van Griensven M, Zeichen J, et al. Cyclic mechanical stretching modulates secretion pattern of growth factors in human tendon fibroblasts. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;86:48. doi: 10.1007/s004210100502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viidik A, Gottrup F. Mechanics of healing soft tissue wounds. In: Schmidt-Schonbein G. In: Woo S, et al., editors. Frontiers in Biomechanics. New York: Springer; 1986. p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson MA. Acute wound failure. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:607. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]