Abstract

We have generated a xenogeneic vaccine against human carcinoembryonic antigen (hCEACAM-5 or commonly hCEA) using as immunogen rhesus CEA (rhCEA). RhCEA cDNA was codon-usage optimized (rhCEAopt) and delivered by sequential DNA electro-gene-transfer (DNA-EGT) and adenoviral (Ad) vector. RhCEAopt was capable to break tolerance to CEA in hCEA transgenic mice and immune responses were detected against epitopes distributed over the entire length of the protein. Xenovaccination with rhCEA resulted in the activation of CD4+ T-cell responses in addition to self-reactive CD8+ T-cells, the development of high-titer antibodies against hCEA, and significant antitumor effects upon challenge with hCEA+ tumor cells. The superior activity of rhCEAopt compared with hCEAopt was confirmed in hCEA/HHD double-transgenic mice, where potent CD8+ T-cell responses against specific human HLA A*0201 hCEA epitopes were detected. Our data show that xenogeneic gene-based vaccination with rhCEA is a viable approach to break tolerance against CEA, thus suggesting further development in the clinical setting.

Introduction

Cancer vaccination strategies rely on the evidence that cancer cells, as a consequence of the presence of several epigenetic and genetic changes, achieve a protein expression pattern significantly different from their natural counterparts. Intracellular processing and presentation of differentially expressed proteins end up in the display on the surface of cancer cells in the context of MHC class I molecules of a novel repertoire of peptides either mutated or abnormally enriched, which represents a specific signature of cancer cells.1 Therapeutic cancer vaccines have the goal of stimulating the immune system to recognize components of this novel signature, for example, neoepitopes or overdisplayed epitopes, and to generate effector B- or T-cell responses against them.

Proteins differentially expressed by cancer cells and capable of inducing effector immune responses are defined as tumor-associated antigens (TAAs).2 With the exception of mutated antigens, the majority of TAAs are differentiation, overexpressed, cancer-testis, or universal antigens, derived from naturally occurring “self” proteins. This represents a significant hurdle for the development of effective immunotherapy because of the occurrence of immune tolerance against self. In fact, T-cells that respond strongly to these antigens are likely to be eliminated during thymic selection to establish central tolerance to self. It is possible to overcome tolerance through the activation of residual lower affinity/avidity self-reactive T-cells and B-cells, but this remains a major challenge because of the occurrence of mechanisms of peripheral tolerance.3 In this respect, a strategy believed to be helpful is the use of homologous proteins from a different species, called xenoantigens, as immunogens.4

Xenoantigens have been postulated to act as “altered self” proteins, that is, proteins bearing amino acid substitutions in one or more epitopes, which are capable of breaking tolerance through the induction T-cell responses cross-reactive against the endogenous nonmutated TAA. Several studies have been directed to understand the mechanism of action of xenogeneic cancer vaccines, which were able to demonstrate that heteroclitic epitopes, namely, MHC class I or II binding peptides differing in one or more residues between the heterologous, and the homologous protein are responsible for the induction of CD8+ and/or CD4+ cross-reactive T-cell responses.5,6 The advantage of xenoantigens, in particular when large and derived from close animal species, is that the probability to have one or more heteroclitic peptides is relatively high.

The use of xenoantigens for therapeutic vaccination against cancer has been assessed in several preclinical models, where this approach was consistently shown to be more efficacious than vaccination with the corresponding self antigens in the induction of immunogenic responses and therapeutic efficacy4 through different mechanisms of action. For instance, both T-cell and antibody response were induced by xenogeneic alpha-fetoprotein vaccination against hepatocellular carcinoma,7 whereas auto-antibodies were found to block the enzymatic activity of matrix matalloproteinase-2 upon vaccination with xenogeneic chicken homolog.8 In this context, perhaps the most relevant achievement has been the demonstration of clinical efficacy in dogs with melanoma of a xenogeneic DNA vaccine coding for human tyrosinase (TYR) and delivered by a needleless device.9 A plasmid encoding the xenogeneic TYR was administered with a protocol consisting of four biweekly injections followed by boosts every 6 months. This vaccine, named Oncept, significantly improved survival in dogs with metastatic melanoma and, based on this evidence, was market approved by USDA. Since spontaneous cancers in dogs closely resemble by several criteria human cancers both clinically and molecularly, these findings bear important implications in perspective for the treatment of human disease.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEACAM-5 or commonly CEA) was one of the first TAAs to be identified.10 CEA is a GPI-linked membrane glycoprotein whose expression is very high in the fetal colon, but the expression significantly drops in the normal adult colonic epithelium. CEA undergoes re-expression in a high proportion of epithelial cancers, namely, 90% of colorectal, 70% of gastric, pancreatic, and nonsmall cell lung cancers, and 50% of breast cancers, and its release in serum justifies its frequent use as a serological marker of malignancy.11 Although the functional role of CEA in cancer has not yet been fully clarified, high CEA expression has been linked to increase in intercellular adhesions, and promotion of metastasis.12 It has been reported that human medullary thymic epithelial cells express CEA.13 Moreover, peripheral tolerance is also induced by systemically circulating CEA, which promotes tolerization of CEA-specific CD8+ T-cells in the endogenous T-cell repertoire through the co-inhibitory molecule B7H1.14 Therefore, in spite of the broad, elevated, and specific expression of this antigen in several carcinomas, central and peripheral tolerance represent a significant obstacle toward the establishment of anti-CEA immunity and a major challenge for the development of an effective vaccine.

Genetic vaccines represent promising methods to elicit potent immune response against a wide variety of antigens (reviewed in Aurisicchio and Ciliberto15). Among these, intramuscular electro-gene-transfer of plasmid DNA (DNA-EGT) has been shown to be a safe methodology capable to enhance DNA uptake and protein expression in skeletal muscle cells, together with local inflammatory responses that favor the development of immune responses to the target antigen(s) in both small and large animal species (reviewed in Aurisicchio et al.16). Also, adenoviral (Ad) vectors, because of their strong immunogenicity, have been utilized as tools for vaccinations in several studies, including large human clinical trials.17 The two technologies can be combined together in heterologous prime-boost modalities to increase the level of immunogenicity and allow repeated boosting in order to maintain elevated levels of immune responses to target antigen(s) if necessary.15,18

We have previously reported the cloning and characterization of the rhesus homolog of human CEA (hCEA). Rhesus CEA (rhCEA) encodes a protein of 705 amino acids that is 78.9% homologous to hCEA.19 We also showed that rhCEA, when delivered by DNA-EGT and Ad vectors, is capable of inducing immune responses both in nontolerant mice and, more importantly, in tolerant rhesus monkeys. In the present work we have assessed the potency of rhCEA as xenoantigen both in single-transgenic mice for hCEA (CEA.Tg) and in double-transgenic mice for hCEA and for the human MHC HLA-A*0201 human haplotype (HHD/CEA). This is the first report showing that a gene-based xenogeneic vaccine against hCEA is more potent than a hCEA vaccine in tolerant hosts both for immunogenicity and antitumor activity.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid and adenovirus vectors

The plasmids pV1J-hCEA and pV1J-hCEAopt and the Ad vectors Ad5-hCEA and Ad5-hCEAopt, encoding wild-type hCEA and codon-optimized hCEA, have been previously described.20 Similarly, pV1J-rhCEA, pV1J-rhCEAopt, Ad5-rhCEA, and Ad5-rhCEAopt generation is described in Aurisicchio et al.19 DNA plasmids were purified using GigaPrep kits (Qiagen). Adenoviruses were purified through standard CsCl purification protocol and extensively dialyzed against A105 buffer (5 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM MgCl2, 75 mM NaCl, 5% sucrose, 0.005% Tween-20) and stored at −80°C.

Peptides

Lyophilized rhCEA peptides were purchased from Bio-Synthesis (Lewisville) and resuspended in DMSO at 40 mg/ml as previously described;19,20 15mer peptides encompassing the entire antigen sequence and overlapping by 11 residues were subdivided into 4 pools. Both for hCEA and rhCEA, pool A (34 peptides), pool B (45 peptides), pool C (48 peptides), and pool D (53 peptides) had the same composition and concentrations (see Supplementary Fig. S3A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum). Peptides and pools were stored at −80°C.

Mice immunization

C57Bl/6 mice (H-2b) were purchased from Charles River (Lecco). CEA.tg mice (H-2b) and HHD mice were provided by J. Primus (Vanderbilt University)21 and Dr. F. Lemonnier,22 respectively. HHD/CEA mice have been generated by our group.22 All animals were bred under specific pathogen-free condition by Charles River breeding laboratories (Calco) and kept in standard conditions according to ethics committee approval. DNA-EGT was performed in mice quadriceps injected with 50 μg pV1J-hCEA, pV1J-hCEAopt, pV1J-rhCEA, or pV1J-rhCEAopt and electrically stimulated as previously described.19 Adenovirus injection in quadriceps was performed with 1×1010 vp of Ad5-rhCEA or Ad5-hCEAopt in a volume of 50 μl/mouse. Two weeks after the last injection, antibody- and cell-mediated immune responses were analyzed. Vaccination schedules are schematically shown in Figs. 1 and. 4.

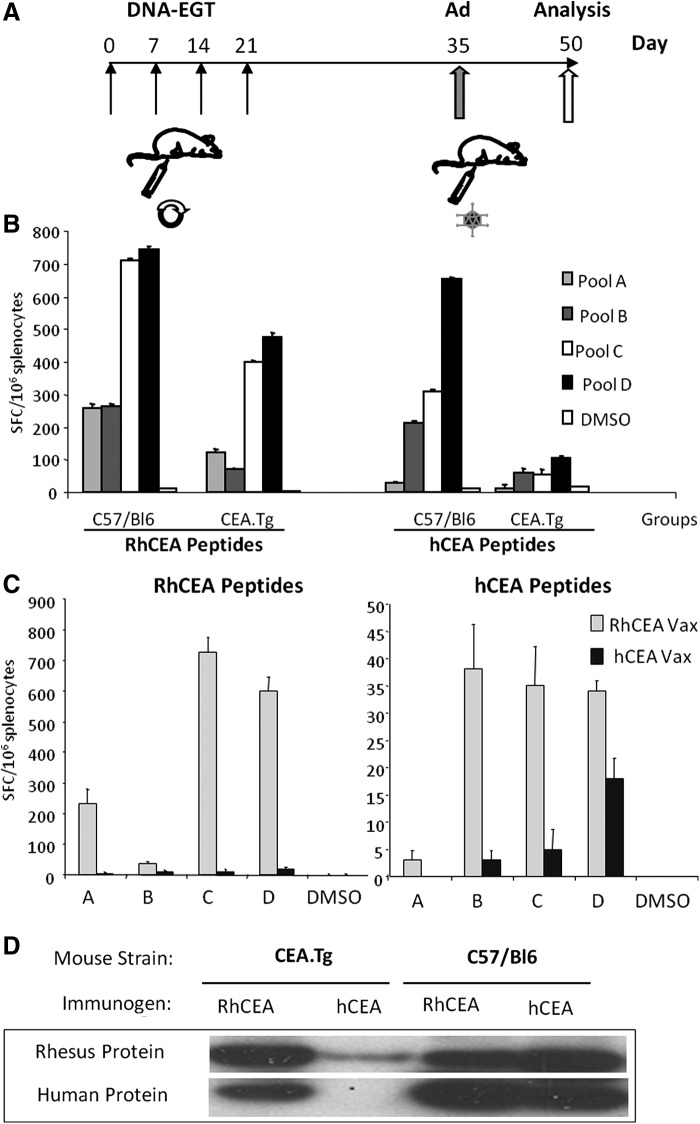

FIG. 1.

Immunization with rhCEA vectors induces cross-reactive response to hCEA and is affected by tolerance. CEA.Tg and C57BL/6 mice (10 mice/group) were vaccinated either with hCEA or with rhCEA-expressing vectors. (A) Vaccination schedule. Mice received 4 weekly injections of plasmid DNA followed by EGT (DNA-EGT), and 2 weeks later they were boosted with Ad5 vectors (Ad). Mice were sacrificed after 15 days and pooled splenocytes analyzed in quadruplicates for immune response. (B) Mice were vaccinated with rhCEA-expressing vectors as described in (A). Cell-mediated immune response was measured by ELISPOT assay using peptide pools encompassing human or rhesus CEA (pools A–D) both in CEA.Tg and C57BL/6 wild-type mice. (C) CEA.Tg mice were immunized either with human or rhesus CEA-expressing vectors. The immune response was measured using hCEA or rhCEA peptide pools. Error bars refer to standard deviations among the wells. (D) Antibody response measured by Western blot as described in Materials and Methods. A band of 180 kDa corresponding to either hCEA or rhCEA was detected using immune sera from mice. The experiment has been repeated twice with similar results. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; EGT, electro-gene-transfer; hCEA, human CEA; rhCEA, rhesus CEA.

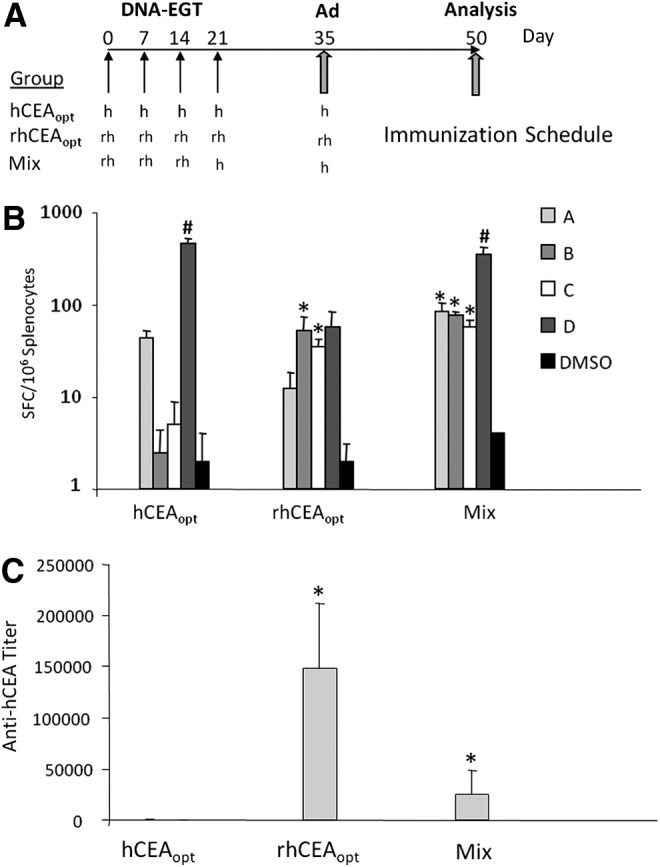

FIG. 4.

Cell-mediated and antibody responses induced by rhCEAopt and combination with hCEAopt. (A) Groups of 10 CEA.Tg mice were vaccinated according to the indicated immunization schedule. h and rh indicates hCEAopt and rhCEAopt vectors, respectively. In Mix modality, the fourth DNA-EGT and the Ad injections encoded hCEAopt immunogen. (B) At day 50, cell-mediated immune response was analyzed by ELISPOT against hCEA peptides. The asterisks (*) indicate significant differences (p<0.02) compared with hCEAopt for each peptide pool, respectively. Number sign (#) indicates a significant difference compared with rhCEAopt (p<0.01). (C) Anti-hCEA antibodies were measured by ELISA. The asterisk (*) indicates significant differences compared with hCEAopt group. p-Values are p<0.0001 and p<0.001 for rhCEAopt and Mix group, respectively.

Tumor challenge studies

Three different models were utilized in this study: CEA.tg mice challenged with (1) subcutaneous (s.c.) or (2) intrasplenic (i.s.) of MC38-CEA cells, and (3) HHD/CEA mice challenged intravenously (i.v.) with B16-HHD/CEA cells. Following vaccination, tumor challenge was performed by s.c. injection of 5×105 MC38-CEA cells/mouse. At weekly intervals, mice were examined for tumor growth, and tumor volume was measured with a caliper and calculated as previously described.20 Mice challenged by i.s. injection of 5×104 MC38-CEA cells/mouse23 were then vaccinated as previously described and followed overtime for survival. This dose of tumor cells is lethal in 100% of mice within 3–5 months after injection if left untreated. MC38-CEA was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 400 μg/ml G418.

HHD/CEA mice were injected i.v. with 5×104 of B16-HHD/CEA cells. This dose of tumor cells is lethal in 100% of mice within 4–6 weeks after transplant if left untreated. Three weeks after challenge, surface metastases were enumerated using an optical microscope (Leica). B16-HHD/CEA cells were previously described24 and were maintained in culture at 10% CO2 in DMEM, 10% FCS with Pen/Strep, and 800 μg/ml G418 and 400 μg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen).

Antibody detection and titration

Sera for antibody titration were obtained by retro-orbital bleeding. Western blot was performed with extracts from HeLa cells transduced with Ad5-hCEA or Ad5-rhCEA run on SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters. Sera from each group were pooled and diluted 1:50 for O/N incubation at 4°C. An anti-mouse IgG-AP conj. (Sigma; 1:2500) was used for the detection. Antibody titer was measured by ELISA assay as described.20

ELISPOT assay and intracellular staining for IFNγ

ELISPOT for mouse IFNγ was performed as previously described.19,20,24 The intracellular staining has been performed according to the procedure described in Giannetti et al.25 Briefly, PBMC or splenocytes were treated with ACK Lysing buffer (Life Technologies) for red blood cell lysis and resuspended in 0.6 ml RPMI and 10% FCS, and incubated with the indicated pool of peptides (5 μg/ml final concentration of each peptide) and brefeldin A (1 μg/ml; BD Pharmingen) at 37°C for 12–16 hr. Cells were then washed and stained with surface antibodies. After washing, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with the IFNγ-FITC antibodies (BD Pharmingen), fixed with 1% formaldehyde in PBS, and analyzed on a FACS-Calibur flow cytometer, using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). DMSO and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (Sigma cat. No. S-4881) at 10 μg/ml were used as internal negative and positive control of the assay, respectively.

T-cell depletion studies

Immunized animals were depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells by intraperitoneal injection of anti-CD4 (GK1.5 hybridoma) and anti-CD8 (Lyt 2.43 hybridoma) antibodies as previously described.26 Briefly, antibodies (200 μg/dose) were injected 7 days before the tumor challenge and then injected every week for 3 weeks after injection of 5×105 MC38-CEA cells. These depletion conditions were validated by flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood, using the following monoclonal antibodies (MAbs): phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4 and peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-conjugated anti-CD8 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen); 99% of the relevant cell subset was depleted, whereas all other subsets remained within normal levels. Tumor growth was monitored on a weekly basis.

In vitro cytotoxicity

Assays were done according to the standard protocols.27 Briefly, lymphocytes were isolated from harvested spleen 2 weeks after the final vaccination, and these cells (2×106/ml) were stimulated with the native peptide along with 20 IU/ml recombinant human IL-2 (Sigma). On day 5, these in vitro stimulated cells were used as CTL effector cells, and the CTL activity was determined by a standard 6 hr 51Cr-release cytotoxicity assay using the RMA-S-HHD cell line as target. Target cells were incubated with effectors at the indicated effector-to-target cell (E:T) ratio. RMA-S-HHD cells (kindly provided by Dr. Lemmonier, Institute Pasteur, Paris) were either loaded for 1 hr with the peptide of interest or treated with DMSO. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS. Specific lysis was calculated as follows: (experimental 51Cr release – spontaneous 51Cr release)/(maximal 51Cr release – spontaneous 51Cr release)×100.

Statistical analysis

Log-rank test, ANOVA test, and two-tailed Student's t-test were utilized where indicated. All analyses were performed in JMP version 5.0.1 (SAS Institute).

Results

A xenogeneic rhCEA heterologous prime-boost vaccine is able to break tolerance in hCEA transgenic mice

To assess the ability of a DNA-EGT prime/Ad boost rhCEA vaccine to break tolerance against hCEA and to generate cross-reactive immune responses, hCEA transgenic mice (CEA.Tg) were vaccinated with a protocol consisting of four weekly DNA-EGT injections followed by one Ad injection two weeks later (Fig. 1A). We have previously shown that this combination is highly efficient in generating immune responses to a variety of immunogens.19,28,29 Two weeks after the Ad injection, cell-mediated immune response was measured by IFNγ ELISPOT using four pools (A, B, C, and D from the NH2 terminus to the COOH terminus of the protein, respectively) of 15mer peptides, overlapping by 11 residues and encompassing the entire rhCEA protein or hCEA. Control wild-type mice (C57BL/6) were vaccinated using the same protocol. Results (Fig. 1B) show that in wild-type mice rhCEA was highly immunogenic with positivity against all four pools, with the highest levels of reactivity against pools C and D (Fig. 1B left). In wild-type mice cross-reactive responses against hCEA peptides were also observed although to a lower level. Also in this case, the strongest reactivity was observed against pools C and D (Fig 1B right). When CEA.Tg mice were vaccinated lower, although still measurable, levels of immune responses were obtained both against “nonself” rhesus peptides (Fig. 1B right) and against self human peptides (Fig. 1B left). The most reactive peptide pools were also in this case pools C and D.

In a second experiment, we compared the immunogenicity in CEA.Tg mice of rhCEA versus hCEA vaccine. IFNγ ELISPOT data in Fig. 1C show that while rhCEA vaccine was, again, able to induce immune response against both the nonself rhesus antigen and the self human antigen, hCEA could elicit only weaker reactivity against the self antigen. Importantly, the level of the immune response against hCEA peptides was higher when using rhCEA as vaccine compared with hCEA (ranging from 2- to 8-fold increase, depending on the peptide pool). This was also confirmed by a Western blotting analysis, which showed that only vaccination with rhCEA was able to induce detectable anti-rhesus and anti-hCEA antibodies (Fig. 1D) in CEA.Tg mice, while C57BL/6 developed a strong antibody response with both hCEA and rhCEA vectors.

These results show that rhCEA is more potent than hCEA both in the induction of T-cell and in antibody immune response in hCEA-tolerant mice.

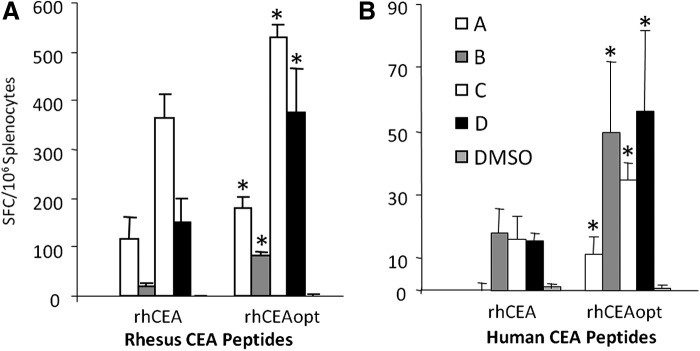

A codon-optimized xenogeneic rhCEA vaccine shows a different pattern of immune response

We and others have previously shown that the use of codon-usage-optimized gene constructs coding for TAAs is able to strongly increase their immunogenicity.15,30 This is likely consequent to increased efficiency of protein translation from the transgene in transduced cells, which causes increased levels of processed and presented and/or cross-presented epitopes by antigen presenting cells. Therefore, in order to increase the level of immune responses to rhCEA, we previously generated a codon-optimized cDNA construct (rhCEAopt).19 We carried out a comparison in CEA.Tg mice with the wild-type cDNA using the same immunization protocol described above. Immune responses were measured by IFNγ ELISPOT both against rhCEA or hCEA peptides. As expected, the data (Fig. 2A and B) show that codon optimization results in enhanced immunogenicity. This is particularly evident in the cross-reactive immune responses against hCEA peptides where values ranged from an average of 15 SFC/106 splenocytes/pool using the wild-type construct to an average of 50 SFC/106 splenocytes with the codon-optimized construct.

FIG. 2.

rhCEAopt is more immunogenic in CEA.Tg mice. Groups of 10 CEA.Tg mice were immunized as shown in Fig. 1A. Cell-mediated immune response was analyzed for each animal by ELISPOT both against rhesus CEA peptides (A, specific antigen response) and hCEA peptides (B, cross-reactive response, breakage of tolerance). Importantly, rhCEAopt was about threefold more efficacious than wild-type gene in eliciting a response against hCEA. The asterisks (*) indicate significant differences (p<0.03) between the response exerted by rhCEA and rhCEAopt for each peptide pool, respectively. The experiment has been repeated twice with similar results.

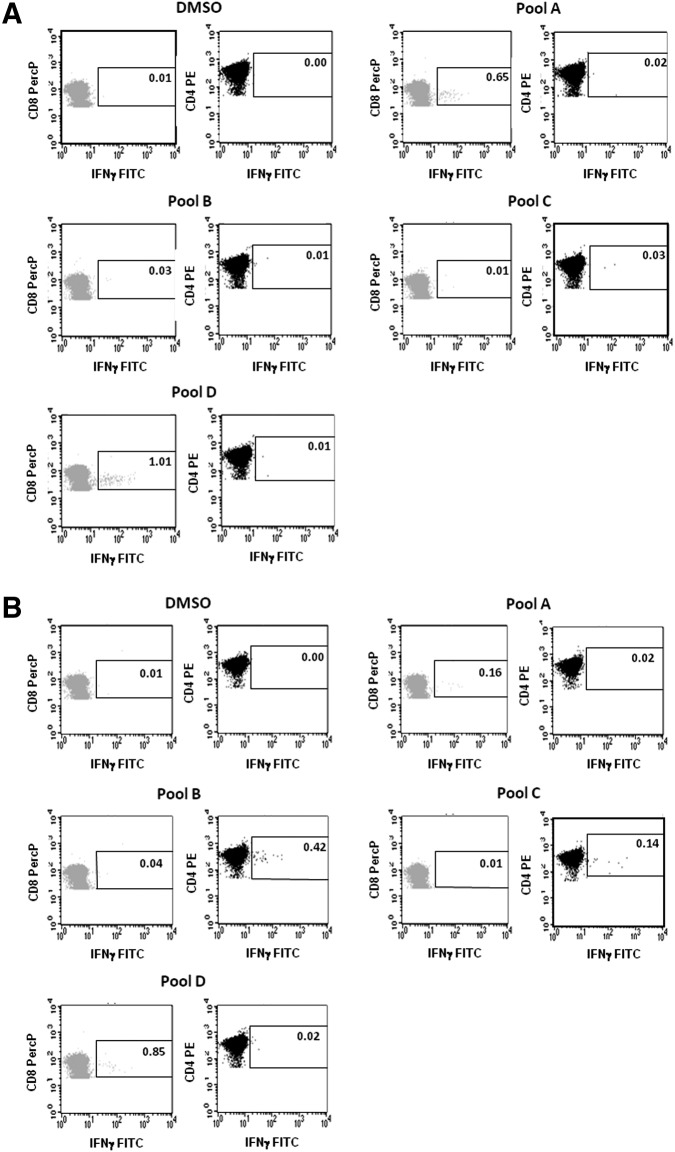

To characterize and determine the quality of the elicited immune response, we also carried out intracellular IFNγ staining using hCEA peptide pools. Results are shown in Fig. 3A and B and indicate that vaccination with codon-optimized hCEA (hCEAopt) was able to induce a strong signal in CD8+ T lymphocytes against pools A and D, but no significant induction of CD4+ T lymphocyte responses (Fig. 3A). In contrast, vaccination with rhCEAopt, while showing similar levels of CD8+ T-cell reactivity to the same two pools, gave rise to additional CD4+ T lymphocyte responses for pools B and C. This finding is of particular relevance since it has been shown that the induction of antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell helper responses is critical in sustaining the activity of cytotoxic effector T-cells over time and to potentiate antitumor activity.31

FIG. 3.

rhCEAopt induces CD8+ and CD4+ responses in CEA.Tg mice. CEA.Tg mice were immunized as shown in Fig. 1A. Cell-mediated immune response was analyzed by intracellular staining for IFNγ two weeks after Ad injection. The reactivity was analyzed with hCEA peptide pools. (A) hCEAopt was used as immunogen. (B) rhCEAopt vectors were used to vaccinate animals. DMSO represents the negative control. The percentage of antigen-specific, IFNγ +cells is indicated in the selected area. CD8+ population is shown in light gray; CD4+ population is indicated in dark gray.

Therefore, the use of codon-optimized rhCEA as immunogen is able to improve not only the amount but also the type of immune response against the self hCEA antigen in a tolerant mouse transgenic model.

Vaccination with codon-optimized rhCEA has a superior antitumor protective efficacy mediated by both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells

It has been previously reported in some preclinical models that mixed prime-boost vaccination protocols in which initial immunizations with a xenoantigen are followed by injection of the self antigen result in superior immunogenicity and antitumor activity as compared with immunizations only with the xenoantigens.32 On this basis, we compared three different protocols as described in Fig. 4A. In all cases, four weekly DNA-EGT injections were followed by a single Ad vector injection two weeks after the last DNA-EGT dose. The first two schedules involved the delivery of hCEAopt or rhCEAopt encoding vectors only. In the last case, three rhCEAopt injections were followed by two hCEAopt immunizations (Mix). In agreement with intracellular IFNγ staining, the results show a stronger reactivity against pools A and D by hCEAopt vectors (Fig. 4B) and again that xenogeneic vaccination with rhCEA results in high levels of immune responses against the self antigen and in particular in stronger multiepitope reactivity to all four pools of peptides. Mix vaccination was able to further increase immunogenicity against the four peptide pools and keep high the response against pool D. Interestingly, when we measured antibody responses by ELISA against hCEA, the most efficient vaccination protocol able to induce high titers of antibodies was the rhCEA-only immunization, followed by the Mix protocol (Fig. 4C). No significant antibody titers were measured upon vaccination with hCEAopt.

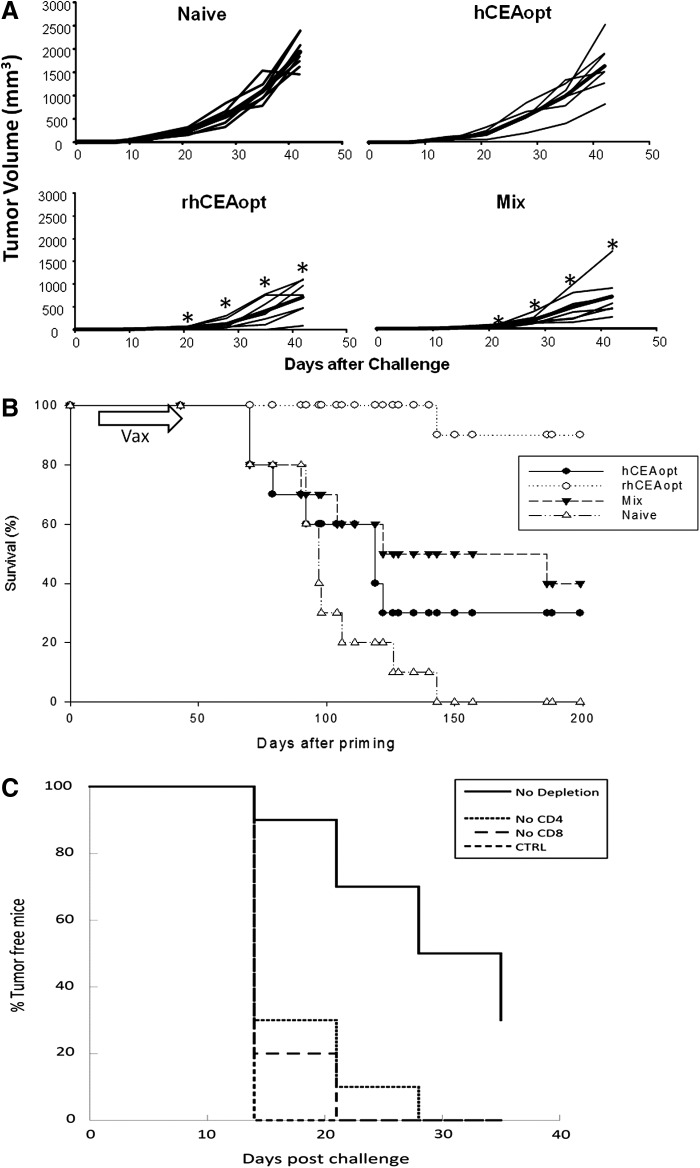

The same three protocols were tested for their ability to provide protective antitumor responses. As a model we used CEA.Tg mice challenged with colon adenocarcinoma MC38 cells stably transfected with hCEA (MC38-CEA).26 Two different models were utilized. In the first one, CEA.Tg mice were first vaccinated and then injected subcutaneously with 5×105 MC38-CEA cells and tumor volume was measured by caliper over time (Fig. 5A). As previously observed, hCEAopt vaccination was not able to confer a significant antitumor effect. On the contrary, both the rhCEAopt and the Mix vaccination schedules resulted in similar tumor growth delay with 40% and 35% tumor reduction at day 40 postchallenge. In a second therapeutic model mimicking liver metastases of colon cancer, 5×104 MC38-CEA cells were injected intrasplenically and 2 weeks later animals were vaccinated and their survival was monitored over time (Fig. 5B). The kinetics of this model allow mounting the immune response in the presence of transplanted cancer cells. We observed that all three vaccination schedules had a statistically significant impact on mice survival. However, the protocol that gave rise to the most prominent positive impact on survival was the rhCEAopt only vaccination.

FIG. 5.

Xenogeneic vaccination exerts superior antitumor effects in CEA.Tg mice. CEA.Tg mice were immunized with hCEAopt, rhCEAopt, or Mix schedule. (A) Two weeks after Ad injection, CEA.Tg mice (7/group) were challenged subcutaneously with 5×105 colon adenocarcinoma cells expressing CEA (MC38-CEA). Tumor volume was measured once a week after challenge. Tumor growth for every single animal and group average (in bold) is shown. Significant differences were observed (t-test, p<0.01) from day 21 onward for rhCEAopt and Mix modality groups compared with control and are indicated by asterisks (*). (B) CEA.Tg mice (12/group) were challenged by i.s. injection with 5×104 MC38-CEA cells. Following this treatment, mice develop gross metastases mainly located to the liver. Two weeks after the injection, mice were vaccinated as previously described or left untreated (naive). Mice survival was then monitored over time. Log-rank test: Naive vs. hCEAopt, p=0.0011; Naive vs. Mix, p=0.0004; Naive vs. rhCEAopt, p=9.98e-07. (C) Depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells abolishes rhCEA protective effects. Groups of 10 CEA.Tg mice were vaccinated as described in the text. Before and after the challenge, mice were injected with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 depleting antibodies. Tumor volume was measured from day 14. The percentage of tumor free mice is shown in the graph. The experiments have been repeated twice with similar results.

We next characterized the effector cells involved in the antitumor effect elicited by immunization with rhCEAopt vectors. After immunization, but before tumor challenge, mice were depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells using MAbs. Antibodies were administered during the course of tumor challenge to ensure continued depletion of the relevant T-cell subsets. Depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells had a negative impact on survival of the immunized mice, resulting in a drastic reduction of tumor-free mice as compared with the vaccinated group (Fig. 5C).

These data indicate that rhCEAopt vectors are efficiently able to achieve antitumor effects and that the mechanism of action is mediated by both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets.

rhCEA vaccination characterization in the HLA-A*0201 context

To evaluate the immunologic outcome of rhCEA vaccination in the context of a different MHC-I, we used the HHD transgenic mice21: these mice express the α1 and α2 domains of the human HLA-A*0201 molecule fused to the α3 domain from the mouse H-2Db molecule and to human β2-microglobulin (HHD) and are a relevant model to study HLA-A*0201-specific immune response. To characterize the immune response elicited by rhCEAopt vectors on this haplotype, HHD mice were vaccinated by DNA-EGT with rhCEAopt or hCEAopt vectors, two injections with an interval of two weeks. Two weeks after the last injection, an ELISPOT assay was carried out with single 15mer overlapping peptides encompassing the full-length rhCEA or hCEA proteins. The HHD immunologic fingerprints showed reactivity to many epitopes distributed throughout the proteins. Upon vaccination with rhCEAopt vectors, strong immune responses (>1000 SFC/million splenocytes) were observed, most of them cross-reactive with hCEA epitopes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Conversely, the vaccination with hCEAopt induced a generally lower immune response with a poor cross-reactivity with rhCEA peptides (Supplementary Fig. S2). Most of the responses induced by rhCEAopt vaccination were CD4+ specific (data not shown).

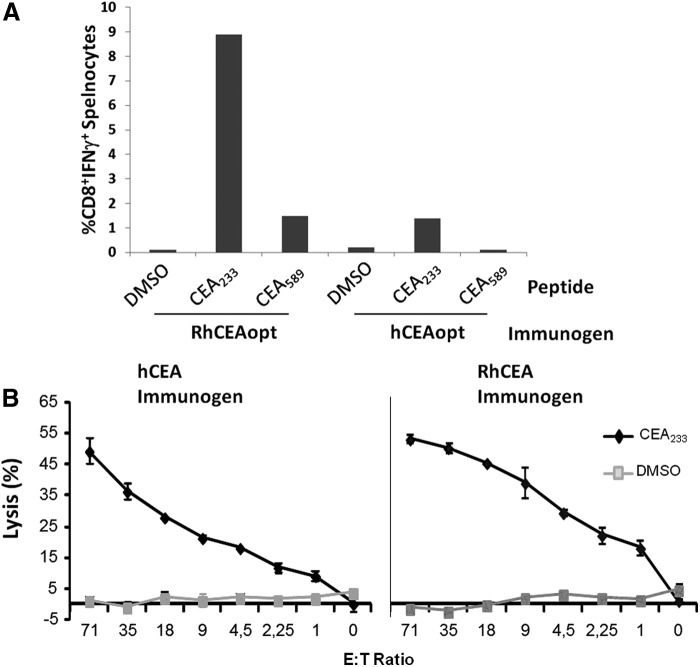

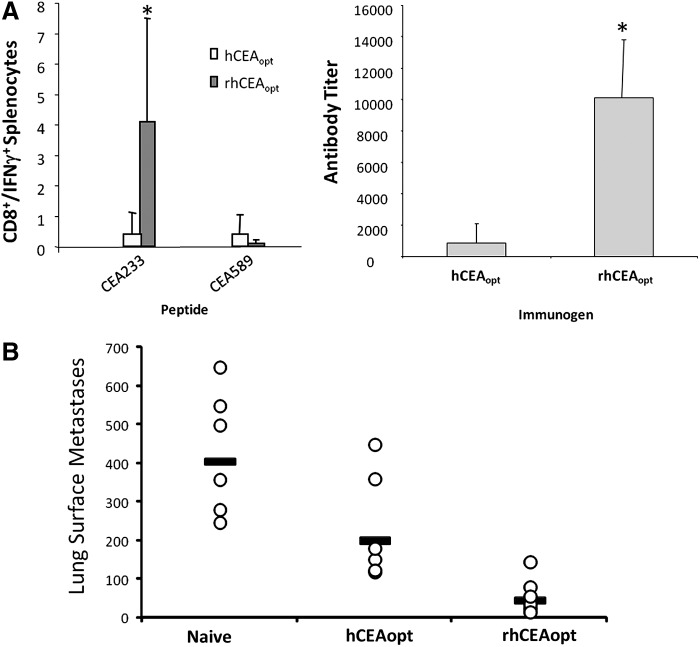

To characterize the effects of rhCEAopt vaccination on HLA-A*0201-specific CD8+ immune response, mouse splenocytes were analyzed by ICS using two CD8+ immunodominant epitopes (CEA233 and CEA589) mapped in the ELISPOT assay and contained within reactive overlapping 15mers. As shown in Fig. 6A, when using rhCEAopt in comparison with hCEAopt vectors, the response was 6- and 9-fold higher for CEA233 and CEA589, respectively. Nonetheless, the killing ability of CEA233-specific CD8+ effectors was similar when using both vectors (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

rhCEA is strongly immunogenic in HHD mice. HHD mice (4/group) were immunized twice with pV1J-rhCEAopt or pV1J-hCEAopt-expressing vectors. Two weeks later, splenocytes were prepared and the immune response was analyzed. (A) Intracellular staining for IFNγ. CEA233 and CEA589 were used to measure specific immune response. DMSO was used as negative control. (B) CTL assay. Effectors were generated upon incubation with peptides for 5 days as described in Materials and Methods. The experiment has been repeated three times with similar results. HHD, human MHC-I haplotype.

These data suggest that rhCEAopt vaccination strategy induces potent and cross-reactive responses also in the HHD haplotype.

Immunologic and antitumor effect of rhCEAopt vaccination in HHD/CEA mice

To evaluate the impact of rhCEAopt vaccination in HHD-specific, CEA-tolerant setting, HHD/CEA double-transgenic mice were vaccinated with rhCEAopt or hCEAopt expression vectors with four weekly DNA-EGT followed by one Ad injection (see Fig. 1A). These mice express hCEA presented exclusively by human HLA-A*0201 molecules and represent a unique in vivo animal model to predict and study human immune response of a hCEA-based vaccine.24,33 The rhCEAopt vectors were able to induce a strong CD8+ immune response against CEA233 epitope that, again, was about 8-fold higher than using hCEAopt vectors (Fig. 7A). On the other hand, CEA589 immunity was strongly impacted by immune tolerance and the signal was comparable between hCEAopt- and rhCEAopt-vaccinated animals. As previously observed in CEA.Tg mice, the antibody titer was much higher with rhCEAopt than with hCEAopt vaccination.

FIG. 7.

rhCEA vaccine breaks tolerance and exerts antitumor effects in HHD/CEA mice. HHD/CEA mice (5/group) were vaccinated with rhCEAopt or hCEAopt expression vectors as described in Fig. 1A. (A) Two weeks after the Ad injection, the immune response against CEA233 and CEA589 epitopes was measured by ICS in PBMCs (left panel) and anti-CEA antibodies monitored by ELISA (right panel). (B) Three weeks after Ad injection, mice were challenged intravenously with B16-HHD/CEA cells. Twenty days later, lungs were explanted and surface metastases counted. Student's t-test: Naive vs. hCEAopt, p=0,044; Naive vs. rhCEAopt, p=0.00029; hCEAopt vs. rhCEAopt, p=0.017.

To assess the antitumor effects in this genetic background, animals were challenged i.v. with a lethal dose of B16-HHD/CEA three weeks after Ad boost. This delivery route leads to colonization and tumor growth in the lungs. Twenty days after the challenge, mice were euthanized, lungs explanted, and surface metastases counted at microscope. A significant reduction in lesions count was observed in mice vaccinated with hCEAopt compared with the untreated group (Fig. 7B). This effect was more pronounced in rhCEAopt-vaccinated animals (Student's t-test, p=0.00029; ANOVA test, p=0.0005).

Taken together, these results show that rhCEAopt vaccine was able to break immune tolerance in HHD/CEA mice and indicate that progression of tumors expressing CEA can be efficiently impaired by the elicited immunity.

Discussion

During the past decades, significant efforts have been directed toward the development of cancer vaccines. However, this approach has not yet been able to meet the expectations. So far, only one therapeutic cancer vaccine has been approved by FDA,34 while several others have failed to demonstrate increase in survival in phase III clinical trials.35 The recent results of the formulated protein-/peptide-based MAGE-A3 and Tecemotide cancer vaccines by GlaxoSmithKline and Merck KGaA, respectively, negatively impacted the cancer vaccine field. Therefore, in light of these drawbacks, renewed efforts are necessary to identify new technology approaches capable to combine vaccine immunogenicity with potent and durable antitumor responses.

In the present study, we have explored the ability of CEA homolog (rhCEA) from rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) to break tolerance in hCEA transgenic mice. These mice are immunologically tolerant and represent a suitable model widely explored to evaluate immunotherapy strategies that have been translated to the clinic (reviewed in Gameiro et al.36). rhCEA is a 705-amino acid protein and shares 78.9% homology to the hCEA protein; therefore, rhCEA has the potential to act as a bona fide “altered self” protein in a hCEA tolerogenic environment.

In our previous work,19 immunogenicity of rhCEA-expressing vectors was tested in wild-type mice and subsequently in rhesus monkeys. To further increase the immunogenic potency of these vectors, a synthetic codon-optimized rhCEA cDNA (rhCEAopt) was generated. Genetic vaccination of rhesus monkeys was effective in breaking immune tolerance to rhCEA in all immunized animals, maintaining over time the elicited immune response, and most importantly, neither autoimmunity nor other side effects were observed upon treatment. Here, we have first observed that a DNA-EGT/Ad-rhCEA vaccination regimen (Fig. 1A) was able to induce a strong immune response against rhCEA but importantly also a cross-reactive immunity to hCEA (Fig. 1B). As expected, the amplitude of the response was affected by the immune tolerance since the reactivity was severely blunted in CEA.Tg mice. In this setting, rhCEA was more immunogenic than hCEA at inducing both T-cell and antibody responses against hCEA (Fig. 1C and D) and codon-optimized vectors showed higher potency (Fig. 2). The elicited immune response was characterized in greater details by intracellular staining (Fig. 3). Despite a similar level of CD8+ immune response, rhCEA vectors were capable of inducing a CD4+-specific response against epitopes contained within pools B and C (Fig. 3B). This observation is in line with the higher overall response observed by ELISPOT and the strong anti-hCEA antibody titer observed in vaccinated mice (Fig. 4).

We hypothesized that an immunization protocol where the first injections aimed at breaking immune tolerance with the xenoantigen (xeno-prime) and the last ones at redirecting the immunity to the homo-antigen (homo-boost) would further increase the anti-hCEA immune response (Fig. 4A). This mixed vaccination schedule was indeed able to provide a widely distributed T-cell response (Fig. 4B), but the xeno-antigen-based protocol was much more efficient in the induction of anti-hCEA antibodies (Fig. 4C). These immunologic outcomes translated in significant antitumor effects in two models of s.c. and metastatic MC38-CEA colon cancer (Fig. 5A and B). In the latter therapeutic model, 90% of mice were cured with rhCEAopt vaccine and survived to the tumor challenge. Despite an higher immune response, the mixed vaccination schedule was not efficacious as rhCEAopt. We do not have a clear explanation for that. We may hypothesize that the last two (specific) vaccinations were not capable of boosting the cross-reactive lymphocytes or that the hCEA expression facilitated a tolerant state in mice. The rhCEAopt vaccine antitumor effects were conferred by both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells, since the selective depletion of both subsets was able to impair the protective effects (Fig. 5C).

The contribution of CD8+ versus CD4+ T-cells or versus antibody responses has been reported in other studies with xeno-antigens. Specific CD4+ immunity has in fact a key role in initiation and maintenance of both antibody and T-cell effector functions. For instance, the direct linkage of Ii-Key (a portion of the MHC class II-associated invariant chain) to MHC class II peptide epitopes greatly enhances the activation of CD4+ T-cells.37 T-cell help is also engaged with strategies based on DNA fusion gene vaccines in which a sequence encoding “promiscuous” MHC class II-binding peptides from a nonself protein is fused with the TAA.38 In line with this strategy, we have previously shown that CEA fusions with the minimized domain of tetanus toxin fragment C (CEA-DOM) or the Fc portion of IgG1 (CEA-FcIgG)26 and the B subunit of Escherichia coli enterotoxin Labile Toxin (CEA-LTB)23 was strongly immunogenic and able to confer antitumor effects. The immunologic mechanisms associated with tumor protection involved the activation of T-cells, NK cells, and high titer anti-CEA antibodies. While for TAAs with intracellular localization the role of CD8+ T-cells represents the main protective mechanism of action, in the case of TAAs expressed on the cell membrane the contribution of antibodies might be determinant.39 This may indeed be the case of rhCEA xeno-vaccination in CEA.Tg and HHD/CEA mice (Figs. 1D, 4C, and 7A). Nevertheless, we have not yet addressed a possible role of antibodies through the induction of ADCC. We are planning passive serum transfer and NK depletion experiments to address this issue.

Several mechanisms may be postulated for the higher T-cell immune response induced by rhCEA vaccine, among them the involvement of a heteroclitic MHC class I and class II epitopes. Initial investigations into the mechanism of action of xenogeneic vaccines suggested dependence from heteroclitic CD8+ T-cell epitopes between the xenoantigen and the self-antigen. These heteroclitic epitopes overcome tolerance by inducing CD8+ T-cell populations that are cross-reactive to both the xenoantigen and to the native antigen.5,6 The best example is the melanoma differentiation antigen gp100. Genetic vectors encoding the mouse (m)gp100 are not immunogenic in mice, while immunization with similar vectors encoding the human (h)gp100 homolog elicits a specific, cross-reactive, and protective CD8+ T-cell response.

The effector T-cells recognize a 9-amino acid gp100 epitope (gp10025–33), restricted by MHC class I H-2Db, which is different in three positions (amino acids 25–27) between the two species. Differences in these three NH2-terminal amino acids result in a 2-log increase in the ability of the hgp10025–33 to stabilize “empty” H-2Db molecules on cells and a 3-log increase in its ability to trigger IFN-γ release by T-cells. No other differences in the two proteins are responsible for this “xeno-vaccination effect.” Therefore, in this case, a single hgp100 heteroclitic epitope with a higher affinity for MHC class I at minor anchor residues was necessary and sufficient to induce protective tumor immunity. However, “altered peptide ligands” may not necessarily confer the ability of induced T-cells to cross-recognize natural epitopes expressed by tumor cells. For example, CAP1-6D, a super agonist analog of a CEA-HLA-A*0201-restricted epitope widely used in clinical setting, has been shown to promote the generation of low-affinity CD8+ T-cells lacking the ability to recognize CEA-expressing colorectal carcinoma cells.40

A heteroclitic MHC class II epitope-dependent mechanism has been described for the melanoma differentiation antigen Trp2 (tyrosinase-related protein 2). Vaccination of mice with human Trp2 results in greater antitumor immunity than vaccination with the murine homolog.41,42 The protective effect is entirely CD8+ T-cell dependent and was because of the development of a cytotoxic response against a peptide that is 100% conserved between mice and humans. However, a dominant heteroclitic MHC class II epitope in human Trp2 is able to induce cross-reactive CD4+ T-cell responses and determine breakage of tolerance against the dominant MHC class I-restricted epitope. This evidence is also important because the strong involvement of cross-reactive CD4+ helper T-cells may be exploited for the induction of high-titer polyclonal antibodies directed against the self-antigen in CEA.Tg and HHD/CEA mice. The amino acid differences between hCEA and rhCEA proteins are indeed distributed along the entire sequence. The fortuitous presence of heteroclitic CD8+ and CD4+ epitopes may therefore determine in part the immunoenhancing properties of rhCEA.

Interestingly, rhCEA was more immunogenic and cross-reactive also in the HHD haplotype (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Figs S1 and S2) and able to break tolerance in HHD/CEA double-transgenic mice (Fig. 7). Since CEA.Tg and HHD/CEA mice share the same genetic background (C57BL/6), it is likely that the activation of CD4+ help enhances the CD8+ and antibody response as previously described. In these mice, the enhancement is mainly because of the reactivity to the epitope CEA233. CEA protein structure is composed by an extracellular amino-terminal IgV-like domain, followed by three (A1, B) IgC2-like domains and the GPI anchor.43 Therefore, the sequences of the three IgC2-like domains are very similar. It is interesting to note that CEA233 sequence is different by a single amino acid between IgC2-like domain 1 and 2 in hCEA (VLYGPDAPT and VLYGPDDPT, respectively) but conserved and identical in rhCEA (Supplementary Fig. S3). Therefore, a potential mechanism of the enhanced immunity may be a higher load and better/improved processing and presentation of CEA233 epitope.

On the other hand, CEA589 epitope contained in IgC2-like domain 3 is identical between the two species, whereas the flanking regions differ and may be differentially processed by proteasome machinery. Of note, despite the higher immunogenicity detected by intracellular staining for IFNγ upon rhCEAopt vaccination, both hCEAopt and rhCEAopt were able to induce highly efficient CTL precursors in HHD mice. However, CTL assays carried out after in vitro expansion with antigens may be misleading in terms of characterizing potency and avidity of responses, since they may be biased by in vitro proliferative capacity of cells and by culture conditions (e.g., peptide concentration used for cell stimulation). Although we have not performed ex vivo CTL assays in HHD/CEA mice, a possible explanation for this observation is that both immunogens in the nontolerant mouse model elicit high-avidity CTL effectors endowed of maximal killing activity. In a tolerant setting, rhCEAopt vaccination may mediate the induction of CTLs with higher affinity and avidity, thus explaining the better antitumor outcome.

Our study provides the basis for the evaluation rhCEA xenogeneic vaccination approach in human clinical trials. We have recently reported the results of two phase 1 trials aimed at evaluating the safety/tolerability and immunogenicity of V930, a mix of two DNA plasmids expressing CEA-LTB and the extracellular/transmembrane portion of HER2/neu delivered with EGT and followed by V932, an Ad serotype 6 encoding the same antigens.44 This study showed that the immunization regimens were safe and well tolerated. However, vaccinated patients had no measurable cell-mediated and antibody responses to self antigens (CEA or HER2/neu), whereas an immune response to the bacterial portion of the vector (LTB, nonself) was detected. One drawback of the study was that an heterogeneous patient population in terms of tumor types and clinical stage was enrolled in the trial. While the immune enhancing properties of LTB in rodent species have been clearly assessed by our group,18,23 this clinical study did not address whether this adjuvant can enhance the immune response against a fused antigen in humans. In contrast, rhCEA is devoid of nonself portions of viral or bacterial origin and may act as a pure xeno-antigen by means of the mechanisms here described.

In conclusion, our data provide evidence in support of xenogeneic gene-based vaccination with rhCEA as a viable approach to break tolerance against hCEA and suggest that this approach should be considered for further development of immunotherapies in the clinical setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

L.A.'s work was supported in part by the grant AIRC IG 10507. We thank Cinzia Roffi for editorial assistance.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Guo C, Manjili MH, Subjeck JR, et al. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: past, present, and future. Adv Cancer Res 2013;119:421–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P, et al. Tumour antigens recognized by T lymphocytes: at the core of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohr J, Knoechel B, Nagabhushanam V, et al. T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity to systemic and tissue-restricted self-antigens. Immunol Rev 2005;204:116–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavallo F, Aurisicchio L, Mancini R, et al. Xenogene vaccination in the therapy of cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2014;14:1427–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overwijk WW, Tsung A, Irvine KR, et al. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of “self”-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med 1998;188:277–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold JS, Ferrone CR, Guevara-Patiño JA, et al. A single heteroclitic epitope determines cancer immunity after xenogeneic DNA immunization against a tumor differentiation antigen. J Immunol 2003;170:5188–5194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Liu J, Wu Y, et al. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma with a vaccine based on xenogeneic homologous alpha fetoprotein in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;376:10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su JM, Wei YQ, Tian L, et al. Active immunogene therapy of cancer with vaccine on the basis of chicken homologous matrix metalloproteinase-2. Cancer Res 2003;63:600–607 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergman PJ, Camps-Palau MA, McKnight JA, et al. Development of a xenogeneic DNA vaccine program for canine malignant melanoma at the Animal Medical Center. Vaccine 2006;24:4582–4585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarobe P, Huarte E, Lasarte JJ, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a target to induce anti-tumor immune responses. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2004;4:443–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maxwell P. Carcinoembryonic antigen: cell adhesion molecule and useful diagnostic marker. Br J Biomed Sci 1999;56:209–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders DS, Kerr MA. Lewis blood group and CEA related antigens; coexpressed cell-cell adhesion molecules with roles in the biological progression and dissemination of tumours. Mol Pathol 1999;52:174–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bos R, van Duikeren S, van Hall T, et al. Expression of a natural tumor antigen by thymic epithelial cells impairs the tumor-protective CD4+ T-cell repertoire. Cancer Res 2005;65:6443–6449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Höchst B, Schildberg FA, Böttcher J, et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells contribute to CD8 T cell tolerance toward circulating carcinoembryonic antigen in mice. Hepatology 2012;56:1924–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aurisicchio L, Ciliberto G. Genetic cancer vaccines: current status and perspectives. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2012;12:1043–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aurisicchio L, Mancini R, Ciliberto G. Cancer vaccination by electro-gene-transfer. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013;12:1127–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JA, Barouch DH, Baden LR. Nonreplicating vectors in HIV vaccines. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013;8:412–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aurisicchio L, Peruzzi D, Koo G, et al. Immunogenicity and therapeutic efficacy of a dual-component genetic cancer vaccine cotargeting carcinoembryonic antigen and HER2/neu in preclinical models. Hum Gene Ther 2014;25:121–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aurisicchio L, Mennuni C, Giannetti P, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a DNA prime/adenovirus boost vaccine against rhesus CEA in nonhuman primates. Int J Cancer 2007;120:2290–2300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mennuni C, Calvaruso F, Facciabene A, et al. Efficient induction of T-cell responses to carcinoembryonic antigen by a heterologous prime-boost regimen using DNA and adenovirus vectors carrying a codon usage optimized cDNA. Int J Cancer 2005;117:444–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke P, Mann J, Simpson JF, et al. Mice transgenic for human carcinoembryonic antigen as a model for immunotherapy. Cancer Res 1998;58:1469–1477 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Firat H, Garcia-Pons F, Tourdot S, et al. H-2 class I knockout, HLA-A2.1-transgenic mice: a versatile animal model for preclinical evaluation of antitumor immunotherapeutic strategies. Eur J Immunol 1999;29:3112–3221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facciabene A, Aurisicchio L, Elia L, et al. Vectors encoding carcinoembryonic antigen fused to the B subunit of heat-labile enterotoxin elicit antigen-specific immune responses and antitumor effects. Vaccine 2007;26:47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conforti A, Peruzzi D, Giannetti P, et al. A novel mouse model for evaluation and prediction of HLA-A2-restricted CEA cancer vaccine responses. J Immunother 2009;32:744–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giannetti P, Facciabene A, La Monica N, et al. Individual mouse analysis of the cellular immune response to tumor antigens in peripheral blood by intracellular staining for cytokines. J Immunol Methods 2006;316:84–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Facciabene A, Aurisicchio L, Elia L, et al. DNA and adenoviral vectors encoding carcinoembryonic antigen fused to immunoenhancing sequences augment antigen-specific immune response and confer tumor protection. Hum Gene Ther 2006;17:81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu J, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, et al. Multiepitope Trojan antigen peptide vaccines for the induction of antitumor CTL and Th immune responses. J Immunol 2004;172:4575–4582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cipriani B, Fridman A, Bendtsen C, et al. Therapeutic vaccination halts disease progression in BALB-neuT mice: the amplitude of elicited immune response is predictive of vaccine efficacy. Hum Gene Ther 2008;19:670–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mennuni C, Ugel S, Mori F, et al. Preventive vaccination with telomerase controls tumor growth in genetically engineered and carcinogen-induced mouse models of cancer. Cancer Res 2008;68:9865–9874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saade F, Petrovsky N. Technologies for enhanced efficacy of DNA vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2012;11:189–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giuntoli RL, Lu J, Kobayashi H, et al. Direct costimulation of tumor-reactive CTL by helper T cells potentiate their proliferation, survival, and effector function. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:922–931 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mincheff M, Zoubak S, Makogonenko Y. Immune responses against PSMA after gene-based vaccination for immunotherapy-A: results from immunizations in animals. Cancer Gene Ther 2006;13:436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aurisicchio L, Fridman A, Bagchi A, et al. A novel minigene scaffold for therapeutic cancer vaccines. Oncoimmunology 2014;3:e27529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:411–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science 2013;342:1432–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gameiro SR, Jammeh ML, Hodge JW. Cancer vaccines targeting carcinoembryonic antigen: state-of-the-art and future promise. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013;12:617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu M, Kallinteris NL, von Hofe E. CD4+ T-cell activation for immunotherapy of malignancies using Ii-Key/MHC class II epitope hybrid vaccines. Vaccine 2012;30:2805–2810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevenson FK, Ottensmeier CH, Johnson P, et al. DNA vaccines to attack cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101 Suppl 2:14646–14652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quaglino E, Mastini C, Amici A, et al. A better immune reaction to Erbb-2 tumors is elicited in mice by DNA vaccines encoding rat/human chimeric proteins. Cancer Res 2010;70:2604–2612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iero M, Squarcina P, Romero P, et al. Low TCR avidity and lack of tumor cell recognition in CD8(+) T cells primed with the CEA-analogue CAP1-6D peptide. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2007;56:1979–1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steitz J, Brück J, Steinbrink K, et al. Genetic immunization of mice with human tyrosinase-related protein 2: implications for the immunotherapy of melanoma. Int J Cancer 2000;86:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kianizad K, Marshall LA, Grinshtein N, et al. Elevated frequencies of self-reactive CD8+ T cells following immunization with a xenoantigen are due to the presence of a heteroclitic CD4+ T-cell helper epitope. Cancer Res 2007;67:6459–6467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnett TR, Drake L, Pickle W., 2nd Human biliary glycoprotein gene: characterization of a family of novel alternatively spliced RNAs and their expressed proteins. Mol Cell Biol 1993;12:1273–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diaz CM, Chiappori A, Aurisicchio L, et al. Phase 1 studies of the safety and immunogenicity of electroporated HER2/CEA DNA vaccine followed by adenoviral boost immunization in patients with solid tumors. J Transl Med 2013;8:11–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.