Abstract

Purpose

College is often a time of alcohol use initiation as well as displayed Facebook alcohol references. The purpose of this longitudinal study was to determine associations between initial references to alcohol on social media and college students’ self-reported recent drinking, binge drinking and excessive drinking.

Methods

First-year students from two US public universities were randomly selected from registrar lists for recruitment. Data collection included 2 years of monthly Facebook evaluation. When an initial displayed Facebook alcohol reference was identified, these “New Alcohol Displayers” were contacted for phone interviews. Phone interviews used the validated TimeLine FollowBack method to evaluate recent alcohol use, binge episodes and excessive drinking. Analyses included calculation of positive predictive value and Poisson regression.

Results

A total of 338 participants were enrolled, 56.1% were female, 74.8% were Caucasian and 58.8% were from the Midwestern university. A total of 167 (49.4%) participants became New Alcohol Displayers during the first two years of college. Among New Alcohol Displayers, 78.5% reported past 28-day alcohol use. Among New Alcohol Displayers who reported recent alcohol use, 84.9% reported at least one binge episode. Posting an initial Facebook alcohol reference as a profile picture or cover photo was positively associated with excessive drinking (RR=2.34, 95% CI: 1.54–3.58).

Conclusions

Findings suggest positive associations between references to alcohol on social media and self-reported recent alcohol use. Location of initial reference as a profile picture or cover photo was associated with problematic drinking, and may suggest that a student would benefit from clinical investigation or resources.

Keywords: adolescent, college student, alcohol, Facebook, drinking behavior, self-disclosure, internet

INTRODUCTION

The transition from high school to college is a high-risk time for alcohol use initiation and escalation. Alcohol is the most commonly used substance by college students,[1] and approximately 20% of adolescents initiate heavy drinking in college.[2] For other students, college is associated with a shift from experimentation to frequent or excessive alcohol use.[3] These trends are concerning because underage drinking contributes to the leading causes of death among adolescents aged 12 to 20 years: unintentional injury, homicide and suicide.[4] Furthermore, problem alcohol use is associated with morbidities such as injury and unwanted sexual encounters.[5, 6]

Early identification of college students at risk for alcohol-related harm can lead to early intervention. Although excellent screening instruments and validated interventions for problem alcohol use exist,[7] many college students do not seek preventive care and are rarely screened for alcohol problems.[8] One innovative and complementary approach towards identifying college students at risk for problem alcohol use and related harms may be using social media such as Facebook. Over 90% of college students use Facebook; students frequently display references to alcohol use as well as problem drinking on their profiles.[9–13] Most displayed content on Facebook is date and time-stamped; thus this site offers opportunities for viewers to identify newly displayed alcohol references that may be proximal to alcohol behaviors in “real-time.”

Past work illustrated that displayed alcohol references on Facebook were positively associated with self-reported alcohol use in cross-sectional samples.[14, 15] However, whether posted content on Facebook is reflective of real-time offline alcohol behaviors is unknown. Most college students do not display alcohol references on Facebook prior to arrival at college,[16] thus, a college student’s initial displayed Facebook alcohol reference may represent recent initiation of alcohol use. It may also represent ongoing alcohol use but the new integration of alcohol into the student’s online identity. Alternatively it may represent intention to engage in future use, or an attempt to brag or fit in to a new environment in which alcohol may be a social norm.[17]

Further, the location of alcohol displays on the Facebook profile affects their visibility, impacting viewer access to this information. Displayed alcohol references may be present in a variety of Facebook locations, including “Likes,” photographs or status updates. For example, the Facebook profile picture or cover photo may be considered closely tied to a profile owner’s online identity and is typically viewable accessible regardless of security settings. In contrast, a displayed alcohol reference among Facebook “Likes” may be one of hundreds of other Likes and thus easily overlooked, or hidden from view by privacy settings.

In this work, we sought to understand how Facebook might be used to identify underage college students engaged in problem drinking. If the timing or content of an initial displayed alcohol reference is associated with recent alcohol behaviors, then opportunities may exist for adults or peers within the Facebook network to approach the student and potentially help facilitate timely and targeted alcohol screening or education. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate underage students’ initial displayed alcohol reference on Facebook across their first two years of college, and evaluate the relationship between location of that display and self-reported alcohol use including recent drinking, binge drinking and excessive drinking.

METHODS

This longitudinal mixed-methods study included evaluation of references to alcohol displayed on Facebook using content analysis and self-reported alcohol behaviors using participant interviews throughout the early matriculation of college.

Setting

This study included two large state universities, one in the Midwest and one in the Northwest. Data for this study was collected between May 15, 2011 and June 18, 2013. This study received approval from the two relevant Institutional Review Boards.

Participants and recruitment

Graduated high school seniors who were planning to attend one of the two participating universities were recruited the summer prior to their first year of college. Potential participants were randomly selected from the registrar’s lists of incoming first-year students from both universities for recruitment. Participants were eligible if they were between the ages of 17 and 19 years and enrolled as a first-year student for fall 2011 at one of these two universities.

Students were recruited through several steps, beginning with a pre-announcement postcard. Over a 3–4 week recruitment period potentially eligible students were contacted with a maximum of 4 rounds of emails, phone calls or Facebook messages. Students were excluded if they had already arrived on campus for summer early-enrollment programs, were an age other than 18 or 19, were non-English speaking or did not have a Facebook profile.

Consent process and Facebook friending

During the consent process potential participants were informed that this was a longitudinal study involving intermittent phone interviews about substance use and social media, and Facebook friending a research team profile. When two Facebook profiles are “friended” this allows profile content to be mutually accessible. Participants were informed that their Facebook profile content would be viewed, but that no content would be posted on the participant’s profile by the research team. Participants were asked to maintain open security settings with the research team’s Facebook profile for the duration of the study.

Interview

Interview procedure

This study included two types of interviews: baseline and prompted. Baseline phone interviews were conducted with all participants at the time of enrollment to obtain demographic data and baseline alcohol experience information. For each 28-day Facebook coding period, if initial displayed references to alcohol were identified by a coder then the participant was contacted to complete a prompted phone interview within the 28 days following the date the reference was evaluated on Facebook. This 28-day window allowed self-report data to be captured using the 28-day TimeLine FollowBack (TLFB) technique described below. Interviews were conducted by trained staff at a time convenient for the participant and lasted 30–50 minutes. Interview data was recorded using a FileMaker database.

Interview data

Both baseline and prompted interviews assessed lifetime and past 28-day alcohol use. Lifetime alcohol use was assessed with the question: “Have you ever had a drink of alcohol in your lifetime?” Current alcohol use was assessed with the question: “In the past 28 days, have you had any drinks of alcohol?”

For participants who reported past 28-day alcohol use, we used the TLFB method in which the interviewer works with the participant to review each day of the past 28 days to assess how many standard alcohol drinks were consumed.[18] The TLFB method produces the following outcomes: total number of alcoholic drinks in the past 28 days and total calculated number of binge drinking episodes in the past 28 days.

At baseline, interviews assessed demographic data including age, gender, ethnicity/race and university.

Facebook coding

Coder training to identify displayed Facebook alcohol references

The coder training period began with a trainee reviewing an established coding manual[19] and observing trainers. Trainee coders then progressed to supervised preliminary coding. In this stage, trainee coders practiced with training datasets and coded data was reviewed and discussed with trainers. Once competency was achieved through evaluation of interrater reliability with trainers on practice datasets, coders began assessing study data. Initial coder training lasted approximately 6–8 weeks. For ongoing training, weekly meetings of all coders provided opportunities to review key coding rules and discuss difficult or unique cases. Interrater assessments were conducted by all coders by evaluating a sample of 10% of study profiles over a 3 month period each year using Fleiss’s kappa.[20]

Coding procedure

The baseline evaluation of each participant’s Facebook profile included content from a three month period during the spring of the participants’ senior year of high school. Upon matriculation, Facebook profile content was evaluated every 4 weeks for each preceding period.

Our standard process was used to evaluate displayed alcohol references on Facebook, described in previous publications and studies.[17, 19, 21] A displayed alcohol reference was defined applying the Theory of Planned Behavior framework, which supports the importance of attitudes and intentions in predicting behaviors.[22–24] Accordingly, displayed references that addressed attitudes, intentions or behaviors regarding alcohol were considered alcohol references, though coders did not categorize alcohol references as such.

During each profile evaluation, coders systematically evaluated the Facebook profile to assess whether displayed alcohol references were present. Facebook profile locations included: 1) the Facebook Wall including status updates and wall posts, 2) photographs including albums, tagged photographs (i.e. photographs that have been labeled by the profile owner or an online friend with names of people in the picture), profile pictures and cover photographs and 3) Likes section which included businesses and groups the participant had “liked.” Extrapolated data included either a typewritten description of any images or likes, or verbatim text from profiles, and the date and time of the display. Each initial displayed alcohol reference was categorized by profile location. In some cases, the profile evaluation noting initial alcohol display identified displays in multiple locations; these students were classified as having an initial display in each of the locations. For references that included names or other identifiable information, this information was not transcribed.

Coding variables

Profiles with one or more references to alcohol or intoxication in any coding period were considered “Alcohol Displayers.” Example references included personal photographs in which the profile owner was drinking from a labeled beer bottle, text references describing intending to consume alcohol at a party, or “Likes” including alcohol brands. Only photographs that contained the profile owner with a clearly labeled alcoholic beverage were included; thus, ambiguous bottles and “keg cups” such as red solo cups were not considered references to alcohol. Only text references that explicitly mentioned the profile owner’s attitudes, intentions or behaviors towards alcohol were coded as alcohol references. Profiles without any alcohol references were considered “Non-Displayers.”

Over the two years of coding, Fleiss’ kappa was 0.80 for the presence or absence of alcohol references present on profiles indicating near-perfect agreement, and 0.73 for the agreement among all coders for the number of alcohol references indicating substantial agreement.[20]

Analysis

Demographic variables and displayed alcohol references on Facebook were evaluated with descriptive statistics. First, to determine associations between Facebook alcohol display location and alcohol use, we calculated the positive predictive value (PPV) and binomial confidence interval for each of the three alcohol outcomes, including past 28-day alcohol use, binge drinking and excessive drinking.

Second, we used Poisson regression to evaluate the relationship between location of initial display and alcohol outcomes including past 28-day alcohol use, binge drinking and excessive drinking. Adjusted risk ratios (RR) describing the relationship between each Facebook alcohol display location and alcohol outcomes were estimated using modified Poisson regression with robust standard errors.[25] This method is the preferred alternative to logistic regression when an outcome is highly prevalent as with self-reported alcohol use.[25] All p values were 2-sided, and p < .05 was used to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

A total of 338 participants were enrolled in the study, 56.1% were female, 74.8% were Caucasian and 58.8% were from the Midwest university. Our initial response rate was 54.6% and after two years our retention rate was 93.8%. At baseline, prior to starting college, 68 Facebook profiles (20.1%) included references to alcohol.

A total of 167 participants (49.4%) posted an initial Facebook alcohol reference during the first two years of college and were considered New Alcohol Displayers. Among these New Alcohol Displayers, most initial displays emerged during the first year of college (80.2%). The 167 New Alcohol Displayers were 58.7% female, 74.9% Caucasian and 67.8% from the Midwest university. (Table 1) A total of 135 of the 167 New Alcohol Displayers completed interviews following their initial Facebook alcohol display and were included in analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of underage college students from two universities who displayed initial Facebook alcohol references during the first two years of college

| Midwest University n=114 | Northwest University n=53 | Total n=167 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 67 (58.8) | 31 (58.5) | 98 (58.7) |

| Male | 47 (41.2) | 22 (41.5) | 69 (41.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 4 (3.5) | 15 (28.3) | 19 (11.4) |

| Caucasian | 102 (89.5) | 23 (43.4) | 125 (74.9) |

| East Indian | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) |

| Hispanic | 4 (3.5) | 5 (9.4) | 9 (5.4) |

| More than one | 3 (2.6) | 9 (15.1) | 11 (6.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (1.2) |

Characteristics of initial displayed alcohol reference on Facebook

Participants who posted an initial Facebook alcohol reference did so in a variety of locations and multimedia formats. Over half (54.1%) of participants’ initial Facebook alcohol references were text-based status updates. These references were typically personally written text describing alcohol attitudes (i.e. “I love beer”), alcohol intentions (i.e. “Can’t wait for beer pong Friday!”) or alcohol behaviors and experiences (i.e. “Drank too much last night….hung-over”). A large proportion of participants (43.7%) initially displayed a Facebook alcohol reference as a photograph; these photographs often depicted alcohol consumption during college parties or football games. A smaller proportion (8.9%) of participants had an initial displayed Facebook alcohol reference in the Likes section; common examples included the group “National go to class drunk day” or “SHOT SHOT SHOT.” Some participants (8.1%) displayed in multiple locations during the 28-day period in which they initially displayed alcohol reference on Facebook. A small proportion of participants (1.2%) displayed an initial Facebook alcohol reference as their profile picture or cover photo.

New Alcohol Displayers and self-reported recent alcohol use

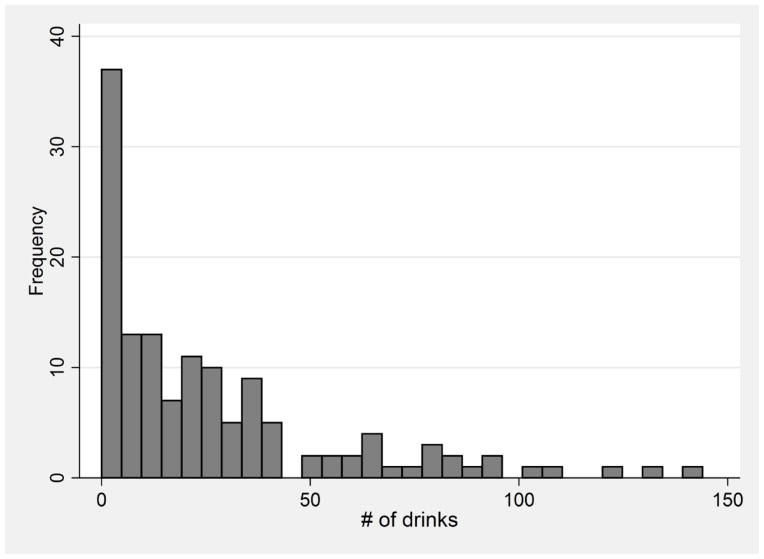

Among the 135 New Alcohol Displayers, 106 (78.5%) reported past 28-day alcohol use. The mean number of alcoholic drinks reported in the past 28 days was 33.6 (SD=30.6); there was variability in number of drinks reported (Figure 1). Of the 106 participants who reported recent alcohol use, 90 participants (84.9%) reported binge episodes; the average number of reported binge episodes was 4.3 (SD=3.8). Among the 90 participants who reported binge episodes, 51 participants (56.7%) reported excessive drinking in the past 28 days.

Figure 1.

Number of drinks reported in past 28 days by first-year college students from two universities

Associations between initial displayed Facebook alcohol reference and alcohol outcomes

Associations between the location of the initial displayed Facebook alcohol reference and reported alcohol use varied. The strongest positive predictive value (PPV) for past 28-day alcohol use was among participants who displayed an initial alcohol reference as a profile picture or cover photo, with a PPV of 100%. The weakest positive predictive value for any alcohol use was among participants who displayed as a “Like” with a PPV of 58.3%. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Positive Predictive Value (PPV) for each Facebook alcohol display location and self-reported past 28-day alcohol behaviors among college students from two universities

| Number (%) with initial display in this location | Outcome: Past 28-day alcohol use reported using TLFBa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any alcohol use | Any binge episodes | Excessive drinkingb | |||||

| Facebook profile location | PPV | 95%CI | PPV | 95%CI | PPV | 95%CI | |

| Status updates | 73 (54.1%) | 75.34 | 63.86 – 84.68 | 57.53 | 45.41 – 69.03 | 31.51 | 21.13 – 43.44 |

| Photographs | 59 (43.7%) | 86.44 | 75.02 – 93.96 | 83.05 | 71.03 – 91.56 | 47.46 | 34.30 – 60.88 |

| Likes | 12 (8.9%) | 58.33 | 27.67 – 84.83 | 50.00 | 21.09 – 78.91 | 33.33 | 9.92 – 65.11 |

| Multiple locations | 11 (8.1%) | 81.82 | 48.22 – 97.72 | 81.82 | 48.22 – 97.72 | 54.55 | 23.38 – 83.25 |

| Profile picture or Cover photo | 2 (1.5%) | 100 | 15.81 – 100 | 100 | 15.81 – 100 | 100 | 15.81 – 100 |

| Prevalence | 106/135 = 78.52% | 90/135 = 66.67% | 51/135 = 37.78% | ||||

TLFB: TimeLine FollowBack

Excessive drinking defined as 4 or more binge episodes in past 4 weeks

Multivariate modeling revealed that key predictors of reporting four or more binge episodes in the past 28 days included an initial alcohol reference display as a profile picture/cover photo (RR=2.34, 95% CI: 1.54–3.58) and an initial display as a photograph (RR=1.79, 95% CI: 1.02–3.15). (Table 3)

Table 3.

Predicting alcohol outcomes among first-year college students by location of initial Facebook alcohol reference display and demographic variables

| Alcohol outcomes in past 28 days Risk Ratio (95% CI)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| VARIABLES | Any alcohol use | Any binge episodes | Excessive drinkingb |

| Initial alcohol reference Facebook location: | |||

| Likes | 0.79 (0.49 – 1.27) | 0.91 (0.53 – 1.57) | 1.16 (0.44 – 3.04) |

|

| |||

| Status update | 1.06 (0.80 – 1.40) | 1.09 (0.82 – 1.44) | 1.22 (0.70 – 2.13) |

|

| |||

| Photographs | 1.17 (0.88 – 1.56) | 1.44** (1.05 – 1.98) | 1.79** (1.02 – 3.15) |

|

| |||

| Profile picture/Cover photo | 1.16 (0.97 – 1.39) | 1.35** (1.06 – 1.73) | 2.34*** (1.54 – 3.58) |

|

| |||

| University: Midwest | 1.22* (0.97 – 1.53) | 0.95 (0.75 – 1.21) | 1.79* (0.94 – 3.39) |

|

| |||

| Gender: Male | 1.08 (0.92 – 1.28) | 1.14 (0.92 – 1.41) | 1.87*** (1.25 – 2.81) |

|

| |||

| Race (White is referent cat.) | |||

| Asian | 0.93 (0.66 – 1.33) | 0.43** (0.20 – 0.89) | 0.45 (0.12 – 1.65) |

| Hispanic | 1.03 (0.58 – 1.81) | 1.11 (0.60 – 2.06) | 2.01** (1.15 – 3.50) |

| More than one | 0.63 (0.31 – 1.30) | 0.33* (0.09 – 1.15) | 0.37 (0.05 – 2.84) |

| Other (omitted in some) | 1.14 | ||

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Risk ratio calculated using Poisson regression with robust standard errors

Excessive drinking defined as 4 or more binge episodes in past 4 weeks

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal mixed-methods study examined Facebook profiles of incoming college students to identify initial displayed Facebook alcohol references and assess recent alcohol behaviors. Findings include that the first year of college is a common time for emergence of displayed alcohol references on Facebook. Initial Facebook alcohol references were positively associated with reporting recent alcohol behaviors. Findings indicate that displaying an initial Facebook alcohol reference in a highly visible location, such as a profile picture, or as a photograph were positively associated with reporting excessive drinking in the past 28 days.

Our first finding was that displayed Facebook alcohol references commonly emerge during the first year of college, a time that is known to be high-risk for the initiation and escalation of alcohol use.[26] Results illustrate that an initial displayed Facebook alcohol reference was commonly linked to self-reported recent alcohol use; over three-quarters of participants who displayed an initial alcohol reference on Facebook reported “real-time” alcohol use within the 28 days of their initial alcohol display on Facebook. Among participants who displayed an initial Facebook alcohol reference and reported recent alcohol use, approximately 80% reported at least one binge episode. Previous studies of national samples have found typical binge drinking rates among college populations of approximately 40%.[2, 27, 28]

Findings also suggest that the location of a first alcohol reference display is important, as some locations on Facebook were more likely to be associated with recent alcohol use compared to others. As a Facebook Like involves a simple click on a predetermined set of text, it may not be surprising that Likes were least likely to be associated with recent alcohol behaviors. It is possible that Likes may represent positive alcohol attitudes rather than behaviors. It may not be surprising that photographs were commonly associated with recent alcohol use, as these pictures suggest a strong form of “evidence” documenting alcohol-related behaviors. A small proportion of participants displayed an initial alcohol reference as a profile picture or cover photo. Participants who chose to incorporate alcohol reference into these profile locations were most likely to report alcohol use as well as excessive drinking. These two locations are among the most visible, accessible and prominent locations on a Facebook profile. Thus, these profile locations may represent importance placed upon alcohol in a student’s new college identity. Displayed alcohol references in these locations are also accessible to any Facebook user regardless of privacy settings.

There are several limitations to our study. First, despite our request for participants to maintain open Facebook security settings with our profile, some participants may have hidden content which we could not detect. Thus, our estimates of alcohol display prevalence are likely conservative. Our conservative coding criteria, which excluded red solo cups, may also contribute to conservative estimates of the prevalence of alcohol displayed on Facebook. It is possible that lighter drinkers may have been more embarrassed by alcohol posts and more likely to conceal them. Further, this study involved viewing Facebook profiles; response bias may have favored recruitment of participants who were willing to make this content available. Second, though we included two large universities in this study with varied locations and student profiles, there was limited racial diversity present. Although the sample represented the diversity present in the schools from which we recruited, our findings may not be generalizable to other institutions or to younger adolescents. Binge drinking rates among our study population were higher than that in national surveys, perhaps because of differing populations, methodologies of Facebook versus survey data, or time periods. Third, the purpose of this study was to determine whether college students’ alcohol-related behaviors, including recent drinking, binge drinking and excessive drinking, were associated with timing and location of initial Facebook alcohol references. Thus, analyses focused on participants who displayed an initial Facebook alcohol reference in the first two years of college. Finally, our study utilized self-reported alcohol behavior measures, which may be subject to social desirability or recall bias. We used the TLFB method to assess recent alcohol use, which has strong validity to support its use.[18]

Despite these limitations, our study has important implications. Previous work illustrated cross-sectional associations between alcohol content on Facebook and problem drinking behaviors;[14, 15] this study extends these findings to establish the real-time relationship between initial Facebook alcohol references and recent offline alcohol consumption. Findings suggest that peers, trusted adults or even parents who view concerning alcohol references on Facebook could seize the moment to inquire about recent alcohol experiences. Our previous work found that approximately 2/3 of college students had at least one parent on Facebook, and among these students 2/3 reported being Facebook friends with a parent; only 20% hid any Facebook content.[29] As adults are the fastest growing demographic on Facebook, it is ever more likely that a caring adult may be able to identify students at risk based on Facebook displays.[30] When approached in an inquisitive and caring manner, previous work suggests that college students would be open to discussions about displayed content.[31]

Our study findings also have implications for researchers considering methods to explore displayed alcohol content on social media. Many new “big data” techniques (i.e. techniques to capture data from large data sets such as Twitter) rely on computer programs to collect text-based data based on keyword recognition. In this study, almost half of initial alcohol displays on Facebook were image-based, and our findings indicate that photographs had a stronger association with self-reported behaviors compared to text-based references. This finding is supported by Media Richness Theory which describes that richer data, such as images, provides a deeper understanding of context and situation to those who experience this data.[32–34] These image-based displays may escape a text-based data collection program, leading to an incomplete understanding of the prevalence and validity of displayed alcohol references. Thus, big data approaches to analyzing social media may wish to consider complementary approaches to avoid missing this important image data, especially if wishing to include those most likely to have significant alcohol-related risks.

Future work should include consideration of intervention possibilities both offline and online. Parents are among the fastest growing populations on Facebook and may be the first to note concerning Facebook displays.[13, 35] College orientation sessions for parents may wish to include information regarding how to identify concerning alcohol references on Facebook and teach strategies for approaching a college student when concerning displays are present.[36] Dormitory resident advisors are another group who may view initial alcohol displays by dormitory residents and thus be in a unique position to initiate discussions about safe alcohol use when initial alcohol displays are identified.[37] As today’s college students often use sites such as Twitter and Instagram in addition to the most commonly used site of Facebook, complementary evaluations of these sites should be considered.[11–13, 38] Future work could assess whether prevention messages or online interventions tied to real-time displays are feasible on social media.[13]

Implications and Contribution.

We evaluated college students’ Facebook profiles monthly for two years to identify initial displayed alcohol references. Alcohol references displayed in prominent Facebook locations such as profile pictures were associated with self-reported recent problematic drinking; these publicly available photographs could identify students who may benefit from clinical screening or resources.

Highlights.

We followed college students on Facebook to identify initial alcohol references

College students who displayed alcohol on Facebook reported recent alcohol behaviors

Initial alcohol displays as a profile picture indicated recent excess drinking

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01DA031580-03 which is supported by the Common Fund, managed by the OD/Office of Strategic Coordination (OSC). The authors wish to thank Libby Brockman, Alina Arseniev and Lauren Kacvinsky for their help with this study.

Abbreviations

- TLFB

TimeLine FollowBack

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No authors have conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hingson R, et al. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: changes from 1998 to 2001. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:259–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wechsler H, et al. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. J Am Coll Health. 2002;50(5):203–17. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson LD, et al. N.I.o.D. Abuse, editor. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006: Volume II, College students and adults aged 19–45. Bethesda, MD: 2007. NIH Publication No 07-6206. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;(16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–46. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derman KHCM, Agocha VB. Sex-related alcohol expectancies as moderators of the relationship between alcohol use and risky sex in adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:71–77. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming MF, Barry KL, MacDonald R. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. Int J Addict. 1991;26(11):1173–85. doi: 10.3109/10826089109062153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foote J, Wilkens C, Vavagiakis P. A national survey of alcohol screening and referral in college health centers. J Am Coll Health. 2004;52(4):149–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreno MA, et al. Emergence and Predictors of Alcohol Reference Displays on Facebook During the First Year of College. Computers and Human Behavior. 2014;30:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno MA, et al. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and Associations. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):35–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith A, Lee R, Zickuhr K. College students and technology. Pew Internet and American Life Project; Washington: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenhart A, et al. PIaAL Project, editor. Social Media and Young Adults. Pew Internet and American Life Project; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duggan M, Smith A. Social Media Update 2013. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno MA, et al. Associations between displayed alcohol references on facebook and problem drinking among college students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;166(2):157–63. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Hoof JJ, Bekkers J, Van Vuuren M. Son, you’re smoking on Facebook! College students disclosures on social networking sites as indicators of real-life behaviors. Computers and Human Behavior. 2014;34:249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno MA, et al. Emergence and Predictors of Alcohol Reference Displays on Facebook During the First Year of College. Computers and Human Behavior. 2014;30(87–94) doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno MA, et al. A Content Analysis of Displayed Alcohol References on a Social Networking Web Site. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(2):168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobell L, Sobell M. TimeLine Follow-Back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno MA, Egan KG, Brockman L. Development of a researcher codebook for use in evaluating social networking site profiles. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(23):2276–84. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol References on Undergraduate Males’ Facebook Profiles. Am J Mens Health. 2011:413–420. doi: 10.1177/1557988310394341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckman J, editors. Action-control: From cognition to behavior. Springer; Heidelberg: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross V, DeJong W. Higher Education Center: For Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Violence Prevention. US Department of Education; Newton, MA: 2008. Alcohol and other drug above among first-year college students. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wechsler H, et al. Correlates of college student binge drinking. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(7):921–926. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Association, A.C.H. American College Health Association: National College Health Assessment. American College Health Association; Baltimore: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr B, Kacvinsky L, Moreno MA. Society for Research on Child Development. Seattle, WA: 2013. Innovative Prompts for Conversations about Risky Behaviors: College Students’ Display of Facebook Substance Use References to Parents. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duggan M, et al. PIaAL Project, editor. Pew Research Internet. Pew Internet and American Life Project; Washington, DC: 2014. Social Media Update 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno MA, et al. College students’ alcohol displays on Facebook: intervention considerations. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(5):388–94. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.663841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lan YF, Sie YS. Using RSS to support mobile learning based on media richness theory. Computers & Education. 2010;55(2):723–732. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper RB, Cooper RB. Exploring the core concepts of media richness theory: The impact of cue multiplicity and feedback immediacy on decision quality. Journal of Management Information Systems. 2003;20(1):263–299. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dennis AR, Kinney ST. Testing Media Richness Theory in The New Media: The Effects of Cues, Feedback and Task Equivocality. Information Systems Research. 1998;9(3):257–274. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenhart A. Adults on Social Network Sites. Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehill JM, Brockman LN, Moreno MA. “Just talk to me”: communicating with college students about depression disclosures on facebook. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(1):122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kacvinsky LE, Moreno MA. College Resident Advisor Involvement and Facebook Use: A Mixed Methods Approach. College Student Journal. 2014 In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duggan M, Brenner J. Demographics of Social Media Users - 2012. Pew Research Center; Washington, D.C: 2013. p. 14. [Google Scholar]