Abstract

Context

HIV testing in jails provides an opportunity to reach individuals outside the scope of traditional screening programs. The rapid turnover of jail populations has, in the past, been a formidable barrier to offering routine access to testing.

Objective

To establish an opt-out, rapid HIV testing program, led by nurses on the jail staff, that would provide undiagnosed yet infected detainees opportunities to learn their status regardless of their hour of entry and duration of stay.

Design

Jail nurses offered rapid, opt-out HIV testing

Setting

Fulton County Jail (FCJ) in Georgia, United States.

Participants

30,316 persons booked to FCJ.

Intervention

In late 2010, we performed a preliminary evaluation of HIV seroprevalence. Starting January 1, 2011, HIV testing via rapid oral mucosal swab was offered to entrants. In March 2013, fingerstick was substituted. Detainees identified as positives were assisted with linkage to care.

Main outcome measures

To estimate an upper limit of overall HIV prevalence among entrants, we determined seroprevalence by age and gender group. To measure program performance, we checked offer and acceptance rates for tests and rate of linkage to care among previously known and newly identified HIV+ detainees.

Results

The initial seroprevalence of HIV in FCJ was at least 2.18%. Between March 2013 and February 2014, 89 new confirmed positives were identified through testing. During these 12 months, 20,947 bookings were followed by an offer of HIV testing (69.10% offer rate), and 17,035 persons accepted (81.32% acceptance rate). A total of 458 previously and newly identified persons were linked to HIV care. Linkage was significantly higher among those aged 40 years and older (p<0.05).

Conclusions

A nurse-led, rapid HIV testing model successfully identified new HIV diagnoses. The testing program substantially decreased the number of persons who are HIV-infected but unaware of their status and promoted linkage to care.

Keywords: HIV, HIV testing, jail, incarceration, linkage

Introduction

In the U.S., the epidemics of incarceration and HIV overlap. Nationally, approximately 1:6 persons infected with HIV spends time in a correctional facility over the course of a year.1 This overlap can be explained in part by which demographic groups are most affected by each epidemic. Incarceration rates are higher among men compared to women, Blacks compared to Whites, and Southerners compared to those from other regions of the country.2 Incidence of new HIV is higher in men compared to women, Blacks compared to Whites, and the epidemic is spreading fastest in the southeast.3 Not surprisingly, jails in the southeast have been a high yield venue for HIV case-finding.4,5

The CDC recommends voluntary HIV screening in all medical venues, including the medical services of correctional facilities.6 Adhering to these recommendations may help identify some of the 15.8% of Americans infected with HIV but unaware that they are infected.3 The prevalence of undiagnosed HIV in a jail setting has been as high as 28.1% of all HIV infected entrants.7 Most HIV testing programs in criminal justice settings have focused on prisoners, and routine screening in jails is rare.8 Approximately 95% of all U.S. inmates, however, pass only through jails.1 Jail-based testing programs are strategic, but they need to accommodate the rapid movement of persons in and out of jails. HIV testing programs using rapid turn-around technology and jail-based nursing staff are likely to best accommodate the needs of jail health services.

Strategies targeted to jail populations must address rapid turnover rates; the median length of stay in a jail is only 2 to 5 days.9–11 Testing early in the jail stay, preferably on the first or second day of confinement, is likely to reach the greatest number of admittees.12,13 Rapid HIV tests, where preliminary results are available in as little as 60 seconds rather than the several day turnaround for conventional testing, are well-suited for the population dynamics of a jail.10 Deciding which detainees are high risk for HIV may not be time well spent—almost half of all persons diagnosed with HIV in a four-jail HIV demonstration project reported either no risk factors or only heterosexual sex.14 Certain arrest charges (e.g., parole violation) may help predict which detainees have higher odds of testing HIV positive, but a screening algorithm targeting only those with charges associated with high odds ratios would miss 44% of those who are HIV infected.15 Likewise, expending time on risk-reduction counseling is probably unlikely to be cost-effective.16

Studies in hospitals and clinics of nurse-initiated screening show patients participate in testing at higher rates than in settings with physician-initiated testing.17,18 A jail is a venue where nurses tend to have more autonomy than in community hospitals and clinics.19 Having staff nurses in jails provide leadership for a testing program has met with success elsewhere.20 HIV screening programs in some settings can accommodate public health workers delivering testing, but non-staff workers coming from outside the system seldom can have access to detainees 24 hours a day, seven days per week. In this paper, we will describe how a southeastern jail established a nurse-led, rapid HIV screening program, initially as a Centers for Disease Control Demonstration Project.4 Funding for the testing subsequently switched to a grant from the Gilead Sciences FOCUS program, which has been described previously.21 Specifically, we sought to institutionalize the policies started in the earlier, federally funded demonstration project. We wanted to establish both the default of offering HIV testing to all, without attempting to obtain a history of high-risk behavior before testing, and the expectation that all front-line nurses in the intake area were to offer testing.

In this paper, we will describe how a routine, opt-out, rapid HIV testing program has resulted in a substantial number of new HIV diagnoses and linkages to care.

Methods

Study site

As briefly described previously,4 a demonstration project of opt-out HIV testing was implemented at Fulton County (GA) Jail (FCJ), one of the 50 largest jails in country.22 Prior to 2010, the jail tested for HIV by opt-in, conventional testing. For over a decade, health services have been staffed by a private medical vendor through a competitive bidding process. Nursing staff consists of registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs), with the latter greatly outnumbering the former. Most are employed full-time. When there are staffing vacancies, temporary staff members are called, on an as-needed basis. Protection of health information is mandated by law; health care staff must keep health-related information confidential from correctional officers.

FCJ is a detention facility with a rated capacity of 2,652 beds; its census averaged 2,269 persons in 2010 (85.6% of capacity occupied).22 According to data supplied by the jail to the study team, in 2011 there were 41,657 bookings of 37,911 unique persons (some individuals enter more than once in a calendar year). The turnover rate of detainees at FCJ is rapid; the median length of stay for all persons booked is 5 days, and the mean is 22 days. The duration of stays can range from less than an hour to more than a year if a detainee’s case is delayed in going to trial.

Initial Needs Assessment: Seroprevalence Study

In order to estimate the underlying HIV prevalence, and how many persons might be infected but unaware, jail nurses offered conventional opt-out HIV testing to all entrants between July 2010 and September 2010. The prevalence of HIV among tested entrants for each age group by gender was calculated.

To estimate the lower limit of the HIV prevalence in FCJ, the number of persons who tested positive was added to the untested persons who self-reported as being HIV positive. The age and gender distribution of persons booked but neither known positive for HIV nor tested for HIV was determined. Study staff then performed a sensitivity analysis to estimate an upper limit to probable HIV prevalence for the entire population. They assigned HIV prevalence among each untested age-gender group according to the HIV prevalence for the same age-gender group among tested persons or self-disclosing positives. Then the study staff summed the lower limit with the extrapolated number among those who were untested and did not disclose a positive serostatus.

Phase 1: HIV testing by oral mucosal swab

As previously described,4 between January 1, 2011, and March 15, 2012, rapid HIV testing was integrated into the jail entry process. With approval of jail administration, the chief physician and the director of nursing at the jail notified nurses employed by the medical vendor that all detainees who underwent a health assessment at entry should be told, “We will test for TB, syphilis and HIV today.” The detainee would have the opportunity to decline any tests offered.

Study staff provided a three-day, 20-hour, group training session to 20 staff nurses in conducting rapid oral swab testing for HIV via the OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem PA). The test took 20 minutes to develop, and the nurses delivered the negative or “preliminary positive” results. Issues covered in training included the technique of using rapid HIV test kits for point of care testing, and adapting testing and counseling to an environment where face-to-face time with the detainee-patient is brief (~ 20 minutes). Trainers reviewed how to discern who lacks competence to consent (e.g., those who are inebriated). The importance of conveying a non-judgmental attitude during the offer and subsequent testing was stressed. Nurses learned how to address clients’ fear of testing positive. To prepare for interacting with those with preliminarily positive results, the nurses practiced teaching coping skills to colleagues role-playing a newly-identified detainee. To manage patients with a positive result, nurses were instructed to categorize the detainee as having “a mental health issue”. Correctional officers have a pre-existing protocol for dealing with mental health crises, so the healthcare staff would not need to disclose the HIV result to custody staff.

Staff nurse turnover is high and new nurses routinely work in the intake area. Training was still an ongoing need after the initial group training. To address the perpetual necessity to orient new nurses, the nursing shift supervisor and study staff met with new hires and provided one-on-one training on the jail testing protocol. Typically, the new nurses trained in this manner required 20 hours of training before becoming proficient.

Study staff routinely observed nurses, both those trained individually and as a group, to reinforce training. Observation hours varied based on nurse performance. For FCJ, there are 3 nursing shifts 7 days a week. After the first wave of training, we attempted to observe three 8 hour shifts for each of those shifts. Nurses trained one-on-one after the initial training period were observed to confirm proficiency. We provided additional observation if a staff member voiced the need for further assistance, or if we discovered issues with particular nursing staff.

A log was kept on those detainees who underwent testing, but to minimize additional paperwork, we did not ask nurses to collect data on those opting out of testing. There was no increase in the staffing of 2–3 nurses per shift in the intake area. When staffing was short in other areas, such as the jail infirmary, nurse administrators routinely reassigned intake nurses to other locations, leading to shortages in the intake area.

Confirmation of preliminary positive tests and discharge planning

Nurses counseled each new preliminary positive for approximately 15 minutes before referral to the study’s Patient Navigator for further counseling. No paper handouts were given to persons testing either positive or negative because entering detainees have no place to store handouts. Furthermore, in the environment of the intake area, not giving handouts tailored to results helped ensure that all individuals tested had the same interaction. Although there was a measure of auditory privacy, maintaining visual privacy is challenging, and different interactions could lead one detainee to speculate about another detainee’s results.

Entrants with preliminary positive reactions to a rapid test underwent confirmatory laboratory testing via Western blots. Results of confirmatory tests were shared with the detainee-patients before release, and those identified as positives were assisted with linkage to care while incarcerated and in the community upon release. The Infection Control Nurse coordinated initial linkage to in-jail care for persons who were not immediately released. The Patient Navigator helped the client plan care upon release.

Phase 2: HIV testing by fingerstick whole blood sample and enhanced monitoring

The testing program was enhanced with industry funding in early 2013 by: 1) offering testing at multiple points in the entry process; 2) transitioning to a less expensive, more sensitive testing method; and 3) utilizing an electronic tracking system to monitor and enhance linkage rates. The electronic tracking system has been described previously.21

For those who either refused opt-out, rapid HIV testing by nurses at the entry process, or did not have a nursing visit at entry, a second opportunity for testing occured within 14 days during a medical evaluation with either a jail healthcare physician assistant, nurse practitioner or physician. This included detainees who were booked in the facility and immediately sent to court, taken to the medical unit, transported to a local hospital, or presented with hostile behaviors.

Starting in March 2013, a third generation HIV-1/2 test, Uni-Gold™ Recombigen® (Trinity Biotech, Bray Ireland), was used for increased sensitivity. This test took 10 minutes to develop. Approximately 10 registered nurses and licensed practical nurses at the FCJ received this additional training in a classroom setting; one-on-one training was offered to those unable to attend the additional training. In order to preserve resources, nurses were instructed not to test known positives. For quality assurance, the study staff regularly observed the nursing staff and provided feedback. Regular meetings were held with nursing leadership and nursing staff members. In this second phase of the program, using an electronic tracking system facilitated the monitoring of the linkage rates of the newly-diagnosed patients to community primary HIV care upon release.

In July 2013, the INSTI test (bioLytical Laboratories, Vancouver BC Canada) was substituted for the Unigold test. This third test took one minute to develop.

Staff feedback

We orally administered an open-ended questionnaire to nursing leadership at the jail to solicit feedback on the program. Study authors recorded responses.

Analysis

HIV test results were categorized as: 1) negative, 2) new preliminary positive, and 3) previously diagnosed positive. A fourth category, of preliminary positive but later ruled negative, was also possible. Jail medical records and the local health department registry were checked for previous diagnoses of HIV. A confidential database with encoded entries for each individual was maintained at Emory University. We counted persons offered a test, those who accepted, those previously identified as infected, and those who were newly identified as infected. Rates of tests being offered and accepted were calculated. Seroprevalence was calculated by dividing the number of all HIV positive results identified through testing by the total number of tests performed. For all HIV infected persons identified through testing and those who declined testing as known positives, we counted the number of individuals linked to care. The outcome variable “linkage to care” was defined by keeping at least one HIV medical appointment either in jail or after release; confirmation was made via chart review by project staff. Rate of linkage to care was calculated for newly diagnosed persons and those previously known, if we were aware of their status. Associations between age, newness of diagnosis, and linkage to care were assessed by one-tailed, Chi-square analysis, using OpenEpi.23

The Emory University Institutional Review Board reviewed the protocol for the Needs Assessment--Seroprevalence Study and gave it expedited approval. Emory IRB reviewed the protocols for evaluating both phases of rapid HIV testing and determined that the project was public health practice that did not constitute human subjects research.

Results

Needs Assessment--Seroprevalence Study

The acceptance rate for conventional serum testing was 43.2% (2,253 of 5,218 jail entrants). The lower limit of HIV seroprevalence in FCJ was 2.18%, a figure determined through positive tests by opt-in conventional testing and known cases. The sensitivity analysis (if the untested were positive in the same proportion as the tested) gave an estimate of 3.16%.

Phase I Outcomes

As previously described, during the first 14.5 months of the program, when testing was conducted using oral swabs, acceptance of HIV testing was 64.3% (12,141 tested, after 18,869 offers). Fifty-two new diagnoses of HIV were made.

Phase 2 Outcomes

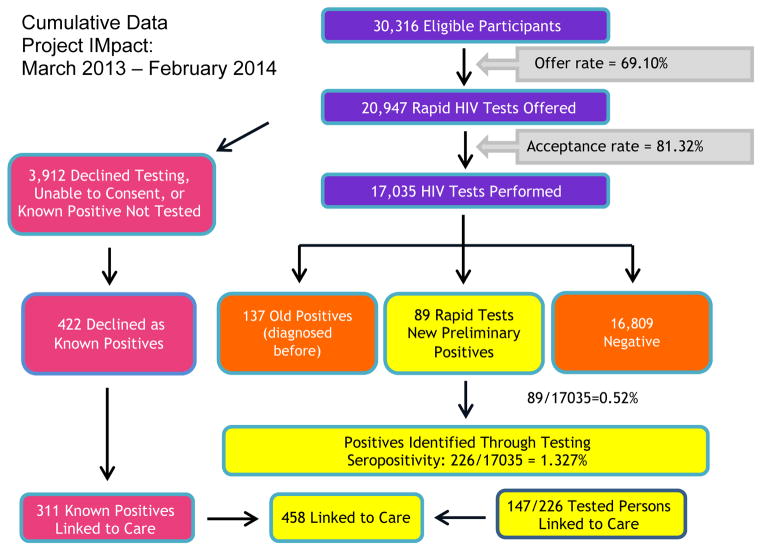

During the second phase of the program, from March 2013 onwards—when fingerstick testing replaced oral swab testing—the test acceptance rates increased to 81.32%. (See Flowchart) Switching from the 20 minute to the 60 second test in July 2013 did not substantially change offer or acceptance rates.

Over the first 12-months of Phase 2, 30,316 persons were booked into the FCJ, and 20,947 (69.10%) were offered testing; 17,035 tests were performed at an acceptance rate of 81.32%. Two hundred and twenty-six positive tests were identified by rapid HIV testing, 89 of which were new preliminary positives (see Flowchart.). All 89 were confirmed by Western blots, and results were given to the detainee-patients before release from the jail. In the first phase of our study, we had one preliminary positive who tested negative on a confirmatory test. However, during the subsequent phase, all new preliminary positives were confirmed as true positives. No false positives were identified in this population with a high pretest probability of HIV.

Of the 3,912 persons who declined testing, 422 declined because they said they were known positives. Of the 89 newly diagnosed with HIV, 20 were aged 40 years or more.. Among those with identified HIV, newly diagnosed individuals were significantly more likely to be younger than 40 years compared with those previously diagnosed. (Chi-square = 27.6; p<.001). All newly diagnosed individuals were informed before release and met with a case manager to discuss linkage to care. A total of 458 persons (59 of the new positives, 88 tested but previously identified positives, and 311 untested but self-disclosed positives) kept at least the first HIV medical appointment either in the jail or after release. See Table 1 for further details. Among all identified HIV+ detainees, detainees aged 40 years or older were more likely to link to care than younger detainees. (Chi-square =2.8; one-tailed p = 0.048). Stratifying by whether diagnosis was new or old, the Breslow-Day test for interaction of odds ratio over strata suggest that there was not significant interaction between age and whether the diagnosis was new in predictions of linkage. (Chi-square=1.7; p=0.19).

Table 1.

Summary of HIV testing results

| Newly Diagnosed HIV+ (N=89) | Previously Diagnosed HIV+ (N=422) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| All HIV+ Identified (New and Previous Positives) (N=511) | Linked to Care (n=59) | Not Linked to Care (n=30) | Linked to Care (n=311) | Not Linked to Care (n=111) | |

| % Male | 91.4% | 91.5% | 90.0% | 92.6% | 88.3% |

| Age | |||||

| <20 | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| 20–29 | 25.4% | 49.2% | 53.3% | 16.7% | 29.7% |

| 30–39 | 25.4% | 30.5% | 20.0% | 25.7% | 23.4% |

| 40–49 | 23.7% | 13.6% | 13.3% | 26.4% | 24.3% |

| 50–59 | 22.0% | 6.8% | 13.3% | 26.4% | 19.8% |

| 60+ | 3.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.9% | 2.7% |

Through the questionnaire we orally administered to the nurses, we were able to collect feedback for the program. From this questionnaire, four central themes emerged: professionalism, training, logistics, and patient issues. More detail on how the nursing staff viewed these issues can be can be found below in Table 2.

Table 2.

Feedback from Nursing Staff Questionnaire

| FEEDBACK FROM NURSING STAFF: |

Professionalism

|

Training

|

Logistics

|

Patient Issues

|

Discussion

Our study has demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of implementing a nurse-led, opt-out rapid HIV testing program in a jail setting in a region with much undiagnosed HIV. This method led to a high number of newly identified cases of HIV and resulted in high rates of linkage to care. The 89 new cases identified over one year in this single county jail compares favorably with the 535 new cases of HIV found per year in all of Fulton County between 2008 and 2011.24

Providing rapid testing addresses the issue of rapid turnover in jails. Because of the tremendous diversity in release patterns of the detainees, rapid testing increases the efficacy for the testing program to deliver the results before detainees leave jails. This program of rapid testing allowed all persons to receive results, in contrast to a program using conventional testing, where only 64% of persons testing positive were notified of results.25 Unlike testing in community venues,26 a medical system is already in place in jails and permits timely confirmatory testing. Also, because a jail health service is a medical system providing care, we were able to obtain feedback from our state and local health department whether positive diagnoses came from persons who had tested previously or were truly new.27 We showed that jails are critical sites for reaching individuals with no or sporadic access to medical services and for delivering interventions to enhance testing and linkage to community HIV care upon release.

By using an integrated model of testing, our program yielded broader testing coverage and increased rates of finding new preliminary diagnoses compared to an external team with limited on-site hours. We believe our program can be disseminated to other jails in the South. In 2013, we made presentations on our program at a meeting of the National Conference on Correctional Healthcare in Nashville, Tennessee; at a neighboring county jail; and at the Metro Atlanta Testing and Linkage Consortium, a city wide meeting of AIDS Service Organizations and local health departments who are involved in HIV testing. Feedback from these audiences indicates that the program is replicative and can potentially address diagnosing HIV among entrants to other area jails by reinforcing jail nurses as leaders in correctional HIV care.

A jail-based HIV testing program has major implications for community health. Both newly diagnosed and previous known HIV positive individuals may benefit from rapid opt-out testing in the jail setting that provides opportunities to address barriers to HIV diagnosis and care and either link or re-engage individuals into routine medical care. In addition to the individual impact of this intervention, jail-based testing and linkage to care can impact the communities to which HIV-infected inmates return. Rapid opt-out HIV testing at jails helps identify new HIV cases that may have otherwise progressed to a later stage of the disease. A previous study in which FCJ participated showed that HIV screening at jails detected cases in earlier courses of disease compared with screening at other types of venues;28 the present study did not assess disease stage at diagnosis. Jail screening programs clearly benefit the newly diagnosed. Providing an opportunity for testing for those not forthcoming about their previous status can also help those who may be in denial about their status. Both groups need linkage to medical care and treatment. If linkage and retention in medical care result from jail testing, then the program represents a valuable public health opportunity to lower the community viral load. The results suggest that youthful detainees may need extra assistance in linking to care.

Limitations and Challenges

In this study, a limitation of determining the yield of testing lies in the potential misclassification of preliminary positives as new cases. Because prior testing results were identified through jail medical records and registries at the local and state health departments, cases that were not previously entered into the registry, or diagnosed outside Georgia, may have been misclassified as new.

Another limitation lies in relying on paper-based nursing logs for tracking data at the front line. An electronic medical record to support routine screening was not in place when the screening described in this paper was started. Currently we are using free-standing electronic tracking systems for managing program data. FCJ has recently begun implementing an electronic medical record system. Soon we may able to track using data generated by this system, which will enhance monitoring of compliance with opt-out HIV testing.

The high turnover of staff nurses in the intake area of the jail necessitated an on-going training program. To combat the effect of high turnover on staff training, future studies may benefit from a more sustainable training program that teaches more permanent nursing staff to provide new hires with HIV training.

Even with ongoing training, there may have been inconsistencies in how the testing was conducted and the reporting was done. A frequent concern of new nurses was the stress of discussing test results with newly diagnosed patients. We overcame this issue by referring to mental health specialists with no untoward effects.

Finally, due primarily to fast inmate turnover, we were not able to oversee that all HIV positive participants were linked to care. Participants with short stays would be tested on intake, but released before staff could schedule appointments with community care. If the jail had no current contact information for these participants, we could not confirm whether they were linked in the community.

Since linkage to care was defined as seeing a provider either in the jail or after release, linkage may have been easier to confirm with longer jail stays. Linkage rates were lower for the young, but the observation that advanced age was associated linkage could be biased either away from or towards the null. The interaction between youthfulness and length of jail stay for comparable charges was not analyzed. Youthfulness could have been associated with shorter criminal records but greater flight risk and thus lower eligibility for bonding out.

Conclusion

Our strategy of integrating HIV testing into nurse services permitted the jail to conduct voluntary testing for over half of the entrants. Furthermore, we found that 0.5% of tests conducted among entrants detected newly diagnosed HIV. The greater Atlanta metropolitan area has five jails with average daily populations greater than 2000 persons; collectively, these jails have over two million admissions a year.22 If the yield of nurse-led rapid HIV testing incorporated into the intake processes of four other jails proves to be comparable to what was found in the successful program at FCJ, then Atlanta could substantially decrease the number of persons who are HIV infected but unaware. We believe that our model of nurse-led, opt-out, rapid HIV testing upon entering a local jail should be replicated both in our region and in other regions of the U.S. heavily impacted by incarceration and where a substantial number of underserved persons are HIV infected but unaware. Determining best practices for linking newly and previously HIV diagnosed detainees to care, especially when the individual is a young adult, needs more research.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Data HIV Testing

March 2013 – February 2014

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dean P. Haire for his help in assembling the data, Ank Nihhawan MD MPH and Laurie Reid RN MA for their helpful comments, and Genetha Mustaafaa MA for putting the linkage system into practice.

Sources of Funding and Support: FOCUS program of Gilead Sciences and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease through the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Spaulding has received grants through Emory University from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Gilead Sciences, and has, as an individual, consulted for Gilead Sciences and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. For the remaining authors, no potential conflicts of interest were declared.

Contributor Information

Anne Spaulding, Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA UNITED STATES.

Min Jung Kim, Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health.

Kiemesha Corpening, Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health.

Taptolia Carpenter, Fulton County Jail.

Portia Watlington, Fulton County Jail.

Chava Bowden, Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health.

References

- 1.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of, and releasees from, US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;11(4):e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison PM, Beck AJ. Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2005. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Department of Justice; May, 2006. [Last accessed 2 January 2007]. NCJ 213133. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/pjim05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas—2011. [Accessed December 9, 2013];HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2013 18(5) http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/2011_Monitoring_HIV_Indicators_HSSR_FINAL.pdf. Published October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spaulding AC, Bowden CJ, Kim BI, et al. Routine Voluntary Opt-Out HIV Screening Into Medical Intake, Fulton County Jail—Atlanta, GA, 2011–2012. MMWR. 2013;62(24):495–497. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macgowan R, Margolis A, Richardson-Moore A, et al. Voluntary Rapid Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Testing in Jails. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36(2):S9–S13. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.1090b1013e318148b318146b318141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Last accessed 2013 April 26];HIV Testing Implementation Guidance: Correctional Settings. 2009 Jan;:1–38. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/testing/resources/guidelines/correctional-settings.

- 7.Begier EM, Bennani Y, Forgione L, et al. Undiagnosed HIV infection among New York City jail entrants, 2006: results of a blinded serosurvey. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2010;54(1):93–101. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c98fa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammett TH, Kennedy S, Kuck S. [last retrieved February 1, 2014];National Survey of Infectious Diseases in Correctional Facilities: HIV and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2007 Mar; Grant 2001-IJ-CX-K018; 99-C-008-T005 Final Report available electronically at http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/217736.pdf.

- 9.Spaulding AC, Perez SD, Seals RM, Kavasery R, Hallman M, Weiss P. The diversity of release patterns for jail detainees: implications for public health interventions. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(Suppl 1):S347–S352. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spaulding AC, Arriola KRJ, Hammett T, Kennedy S, Tinsley M. Rapid HIV testing In rapidly released detainees: next steps. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 36(suppl 2):s34–s36. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e3180959e9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessment of sexually transmitted diseases services in city and county jails--United States, 1997. MMWR. 1998 Jun 5;47(21):429–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kavasery R, Maru DSR, Cornman-Homonoff J, Sylla LN, Smith D, Altice FL. Routine Opt-Out HIV Testing Strategies in a Female Jail Setting: A Prospective Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kavasery R, Maru DSR, Sylla LN, Smith D, Altice FL. A Prospective Controlled Trial of Routine Opt-Out HIV Testing in a Men’s Jail. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGowan RJ, Margolis AD, Richardson-Moore A, et al. Voluntary rapid HIV testing in jails. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318148b6b1. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harawa NT, Bingham TA, Butler QR, et al. Using arrest charge to screen for undiagnosed HIV infection among new arrestees: a study in Los Angeles County. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2009;15(2):105–117. doi: 10.1177/1078345808330038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, et al. Effect of Risk-Reduction Counseling With Rapid HIV Testing on Risk of Acquiring Sexually Transmitted Infections The AWARE Randomized Clinical Trial Risk-Reduction Counseling and Sexually Transmitted Infections Risk-Reduction Counseling and Sexually Transmitted Infections. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1701–1710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anaya H, Hoang T, Golden J, et al. Improving HIV Screening and Receipt of Results by Nurse-Initiated Streamlined Counseling and Rapid Testing. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008 Jun 01;23(6):800–807. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0617-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham CO, Doran B, DeLuca J, Dyksterhouse R, Asgary R, Sacajiu G. Routine Opt-Out HIV Testing in an Urban Community Health Center. AIDS Patient Care & Stds. 2009;23(8):619–623. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaMarre M. Nursing Role and Practice in Correctional Facilities. In: Puisis M, editor. Textbook of Correctional Medicine. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckwith CG, Nunn A, Baucom S, et al. Rapid HIV Testing in Large Urban Jails. American Journal of Public Health. 2012 May 01;102(S2):S184–S186. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez TH, Sullivan PS, Rothman RE, et al. A Novel Approach to Realizing Routine HIV Screening and Enhancing Linkage to Care in the United States: Protocol of the FOCUS Program and Early Results. JMIR research protocols. 2014;3(3) doi: 10.2196/resprot.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minton TD. Jail Inmates at Midyear 2010 - Statistical Tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Apr, 2011. [Accessed 2011 August 27. 2011]. (revised 6-28-2011), NCJ 233431. Available http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/jim10st.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. [accessed 2014/09/29];OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 3.03. www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2014/09/22.

- 24.AIDS Vu. Record for Fulton County GA, in County Data Sets. University, Rollins School of Public Health; [Accessed June 24, 2014]. Available at: http://aidsvu.org/resources/downloadable-maps-and-resources/Emory. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beckwith C, Bazerman L, Gillani F, et al. The Feasibility of Implementing the HIV Seek, Test, and Treat Strategy in Jails. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2014;28(4):183–187. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowles KE, Clark HA, Tai E, et al. Implementing rapid HIV testing in outreach and community settings: results from an advancing HIV prevention demonstration project conducted in seven US cities. Public Health Reports. 2008;123(Suppl 3):78. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spaulding A, Reid L, Bowden C, et al. A Tale of One City, Two Venues: Comparing Costs of Routine Rapid HIV Testing in a High-volume Jail and a High-volume Emergency Department, Atlanta, Georgia. 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 3–6; 2013; Atlanta GA. Abstract 1061. [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeVoux A, Beckwith C, Avery A, et al. Early Identification of HIV: Empirical Support for Jail-Based Screening. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]