Abstract

Purpose

Lab experiments on cigarette warnings typically use a brief one-time exposure that is not paired with the cigarette packs smokers use every day, leaving open the question of how repeated warning exposure over several weeks may affect smokers. This proof of principle study sought to develop a new protocol for testing cigarette warnings that better reflects real-world exposure by presenting them on cigarette smokers’ own packs.

Methods

We tested a cigarette pack labeling protocol with 76 US smokers ages 18 and older. We applied graphic warnings to the front and back of smokers’ cigarette packs.

Results

Most smokers reported that at least 75% of the packs of cigarettes they smoked during the study had our warnings. Nearly all said they would participate in the study again. Using cigarette packs with the study warnings increased quit intentions (p<.05).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest a feasible pack labeling protocol with six steps: (1) schedule appointments at brief intervals; (2) determine typical cigarette consumption; (3) ask smokers to bring a supply of cigarette packs to study appointments; (4) apply labels to smokers’ cigarette packs; (5) provide participation incentives at the end of appointments; and (6) refer smokers to cessation services at end of the study. When used in randomized controlled trials in settings with real-world message exposure over time, this protocol may help identify the true impact of warnings and thus better inform tobacco product labeling policy.

Keywords: smoking, health communication, persuasive communication, government regulation, tobacco products

INTRODUCTION

For much of the world, tobacco product packaging is a key part of marketing efforts to make tobacco use appealing.[1–3] In contrast, warnings on tobacco product packages accurately convey the many health risks of tobacco to discourage smoking initiation and increase cessation.[4] Information on the effectiveness of these warnings can guide policymakers as they consider new warnings and develop regulations. In the more than 100 countries that already have cigarette pack labeling policies in place,[5] testing the impact of potential cigarette pack warnings can guide selection of warnings with the greatest impact.

Research on cigarette pack warnings currently focuses on population-based observational studies of smoking behavior and on laboratory experiments. Longitudinal observational studies have found increased cessation behavior after countries introduced new health warnings on cigarette packs.[6–9] These observational studies have high external validity, but they do not rule out alternative explanations for the association of the changes in labeling and behavior change. Experiments on exposure to cigarette pack warnings in laboratory settings can offer much stronger evidence that warnings cause observed changes in beliefs and behavior.[10, 11] While a large experimental literature has developed, these experiments use very brief exposure to warnings; assess non-behavioral short-term outcomes, such as attitudes or quit intentions, instead of smoking behavior; and, yield results that need corroboration outside of a controlled research setting.

It will be helpful to develop a way to deliver new messages on cigarette packs that smokers use daily in order to expand the external validity of experimental research on cigarette warnings. This will ensure a meaningful warning “dose” that replicates the frequency and duration of warning exposure in the real world. For example, a pack-a-day smoker sees a cigarette pack at least an estimated 7,300 times per year (>20 views/day × 365 days/year).

Several studies have tested warnings by providing mocked-up cigarette packs to participants, but most of these studies used a one-time, brief exposure that does not replicate message dose in the real world.[10, 12–18] At least five studies have used mocked-up packs for a longer period of time.[19, 20] A 2001 study conducted in France, Switzerland, and Belgium mailed 485 adult smokers cardboard boxes with one of four antismoking messages selected by the smoker at recruitment. Study materials instructed participants to place their cigarette packs in the boxes for four weeks, but few did so.[20] A 2010 study in Scotland provided 140 adult smokers with 14 plain cigarette packs that had warnings but no brand information or logos, asking participants to transfer their own cigarettes into the supplied packs for two weeks. Only 34% of participants completed the study as intended.[19] A recent US study provided smokers with free cigarettes and labeled the packs with health warnings for four weeks. During the study, participants collected their cigarette butts and brought them to study appointments. This study used an innovative method for labeling cigarette packs, but the results may have been influenced by receipt of free cigarettes and saving the cigarette butts.[21] Two additional recent studies in the US had smokers apply warning labels to their own cigarette packs, which may be an intervention in its own right, and both studies had short follow-up periods (three to seven days).[22, 23] While these studies’ methods are promising because they more closely replicate real-world message dose, we need strategies with high protocol adherence and longer follow-up periods. Tobacco control research would benefit from a way to test health warnings on cigarette packs that allows for random assignment to warning conditions, adds realism, and maintains high protocol adherence.

To that end, we tested a new cigarette pack labeling and carrying protocol with adult smokers in two proof-of-principle pilot studies. We aimed to assess whether the pack labeling and carrying protocol (1) is feasible and has high adherence for assessing smokers’ reactions to cigarette pack warnings in a real-world setting and (2) is sensitive to changes in psychosocial outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Pilot Study 1

From February to March 2013, we recruited 30 smokers ages 18 or older who we observed smoking cigarettes in public places in North Carolina, USA, or who received referrals from study participants. We defined current smoking as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes during one’s lifetime and now smoking every day or some days, and we excluded pregnant women, people who smoke only roll-your-own cigarettes, and cigarillo-only smokers.

Pilot Study 2

In July and August 2014, we recruited an additional 48 smokers using the same eligibility criteria as Pilot Study 1. We used a variety of recruitment methods, including newspaper ads, flyers, and email lists.

Procedures

Pilot Study 1

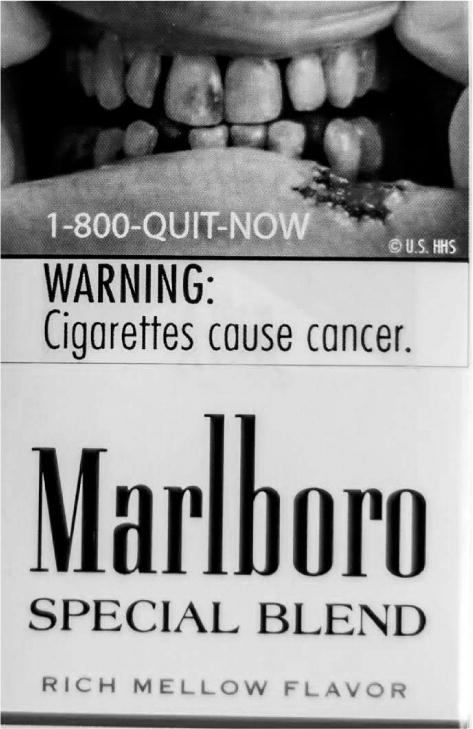

A research assistant explained the study to participants and obtained written informed consent. We provided participants with an $80 financial study incentive in cash and accompanied them to a nearby store, where we asked them to purchase the amount of cigarette packs they would normally smoke over two weeks as determined in the initial screening. We randomly assigned participants to receive one of nine graphic warnings (Figure 1). In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed these nine warnings for implementation, but the warnings were later challenged in court and are not currently in use.[24] At the time of the study, US cigarette packs also included one of four text-only warnings on one side of the pack; these warnings have been in circulation since 1985. Then, participants completed a baseline survey on a tablet computer while staff removed the package cellophane and applied the same graphic warning labels to the top half of the front and rear panels of participants’ cigarette packs, in accordance with the proposed FDA requirements (Figure 1). As applying the labels on the top half of the front panel sealed the flip-top box shut, staff cut through the label to allow the box to again open freely. Participants returned to the study offices to complete a follow-up computer survey two weeks later and received an additional $50 cash incentive. After completing the follow-up visit survey, each participant received information about a local smoking cessation program.

Figure 1.

Example of graphic warning label on pack

Pilot Study 2

Procedures for Pilot Study 2 were similar to Pilot Study 1. After obtaining written informed consent, we randomly assigned participants to receive one of five graphic warnings, four of which were also used in Pilot Study 1. Participants visited our study offices at baseline and then weekly for four weeks, completing a survey on the computer at each visit. Smokers brought eight days’ worth of cigarettes to the first four appointments. While participants were taking the survey, we labeled their packs using the same procedures as in Pilot Study 1. Participants received a cash incentive at the end of each visit in an envelope marked “payment for survey completion.” Cash incentives totaled $185. At the final appointment, each participant received information about a local smoking cessation program. Two of the 48 participants withdrew from the study. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the procedures for both pilot studies.

Measures

Prior to the studies, we refined the survey instruments by conducting cognitive interviews with 17 adult smokers.[25] Baseline and follow-up surveys applied measures adapted from prior studies, including knowledge of smoking health risks (3 items),[26] perceived likelihood of harm from smoking (2 items),[27] worry about the harms of smoking (1 item),[28] subjective norms (3 items),[29] positive smoker prototypes (7 items),[30–32] negative smoker prototypes (5 items),[30–32] self-efficacy to quit smoking (3 items),[29] and quit intentions (3 items).[33] Cronbach’s alpha for multi-item scales was 0.70 or higher in both studies, except for self-efficacy in Pilot Study 1 (α=0.69). We also measured whether participants attempted to quit smoking (defined as not smoking for at least 24 hours because they were trying to quit smoking) or successfully stopped smoking during the study (defined as not smoking for at least seven days).

The follow-up surveys assessed noticing the warning, whether people talked to others about the warning, avoidance of the warning, emotional reactions to the warning,[34] participant satisfaction with study procedures, the number of cigarettes smoked from labeled and unlabeled packs, and unprompted recall of the warning image. Two raters independently coded whether each participant correctly recalled the image in their assigned warning, with perfect agreement.

Finally, in Pilot Study 1, several open-ended questions assessed attitudes toward the study protocol. Two raters independently coded whether open-ended responses indicated that smokers thought the study was giving them free cigarettes. A coauthor resolved all coding discrepancies. The survey instruments are available online: www.unc.edu/~ntbrewer.

Data analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics to summarize demographic information and process measures. We assessed changes between baseline and follow-up using paired t-tests or McNemar chi-squared tests. For continuous variables with non-normal distribution (by Q-Q plots and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests of normality), we used Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, a non-parametric equivalent of the paired t-test. Analyses used SPSS Statistics version 20 and Stata/IC version 13.1. The two Pilot Study 2 participants who withdrew from the study were excluded from analyses. We set test critical alpha value to 0.05 and used two-tailed tests.

RESULTS

Smokers’ mean age was 30 years in Pilot Study 1 and 43 years in Pilot Study 2 (Table 1). Fewer than half of participants were white and about one-third were African American. Most smokers (69% in Pilot Study 1 and 59% in Pilot Study 2) were low-income, defined as being at or below 200% of the US federal poverty level. At baseline, participants in Pilot Study 1 smoked an average of 12 cigarettes per day (SD=9) and participants in Pilot Study 2 smoked an average of 11 cigarettes per day (SD=8).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Pilot Study 1 (n=30) % | Pilot Study 2 (n=46) % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–24 years | 40 | 4 |

| 25–39 years | 33 | 37 |

| 40–54 years | 27 | 33 |

| 55+ years | 0 | 26 |

| Mean (SD) | 30 (11) | 43 (12) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 40 | 57 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Straight | 90 | 89 |

| Gay | 3 | 9 |

| Bisexual | 7 | 2 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||

| No | 90 | 87 |

| Yes | 10 | 13 |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 7 | 4 |

| Black | 27 | 35 |

| White | 43 | 44 |

| Other/Multiracial | 23 | 17 |

| Education | ||

| High school degree or less | 33 | 20 |

| Some college | 50 | 50 |

| College graduate | 10 | 24 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 7 | 7 |

| Low income | ||

| No | 31 | 41 |

| Yes | 69 | 59 |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | ||

| Mean (SD) | 12 (9) | 11 (8) |

Exposure to labels

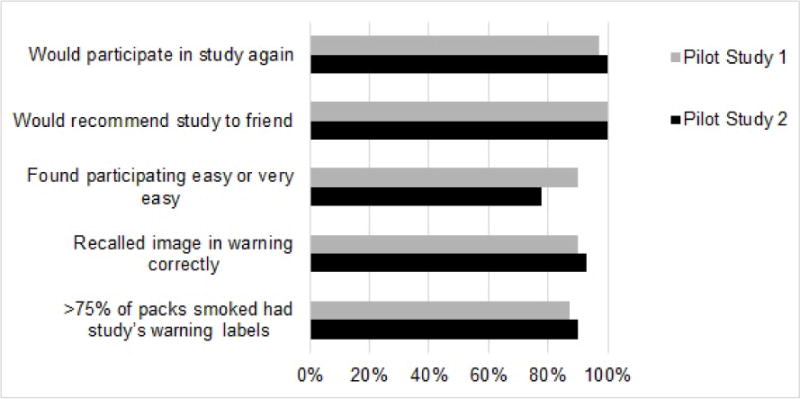

Study participants reported high rates of adherence to smoking cigarettes only from labeled packs. Around 90% of smokers reported that at least three quarters of the cigarettes smoked during the study were from labeled packs (Figure 2). Ninety percent of smokers in Pilot Study 1 and 93% of smokers in Pilot Study 2 correctly recalled the image on their assigned labels. At follow-up, most (93% in Pilot Study 1 and 89% in Pilot Study 2) smokers reported noticing the warning sometimes, often, or all of the time (Table 2). About half of smokers tried to avoid thinking about the labels sometimes, often, or all the time. Similarly, 43% of smokers in Pilot Study 1 and 46% of smokers in Pilot Study 2 tried to avoid looking at the labels sometimes, often, or all of the time.

Figure 2.

Process evaluation measures for cigarette pack labeling proof of principle studies

Table 2.

Outcomes at follow-up.

| Pilot Study 1 (n=30) | Pilot Study 2 (n=46) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 2 week follow-up | 2 week follow-up | 4 week follow-up | |

|

| |||

| % | % | % | |

| Psychosocial | |||

| Noticed the warning1 | 93 | 89 | 78 |

| Talked to anyone about the warnings1 | 97 | 93 | 96 |

| Tried to avoid thinking about the warning1 | 43 | 50 | 30 |

| Tried to avoid looking at the warning1 | 43 | 46 | 35 |

| Felt (as a result of viewing the warning)2: | |||

| Depressed | 10 | 4 | 4 |

| Disgusted or grossed out | 20 | 11 | 7 |

| Guilty | 10 | 11 | 9 |

| Sad | 13 | 7 | 9 |

| Worried or anxious | 20 | 5 | 2 |

| Warning caused them to think about the harmful effects of smoking | 50 | 41 | 39 |

| Behavioral | |||

| Quit attempt, 1 or more days | 10 | 17 | 20 |

| Quit smoking | 0 | 4 | 2 |

Responded “sometimes,” “often,” or “all of the time” rather than “never” or “almost never”

Responded “very” or “completely,” rather than “not at all,” “a little,” or “somewhat”

Outcomes at follow-up

About half (50% in Pilot Study 1 and 41% in Pilot Study 2) of participants reported that the warnings caused them to think about the harmful effects of smoking somewhat, quite a bit, or very much. Almost all participants (97% in Pilot Study 1 and 93% in Pilot Study 2) reported talking to someone about the warnings during the study.

Changes in outcomes

Endorsement of positive smoker prototypes decreased between baseline and follow-up in both studies (p<.05, Table 3). Likewise, quit intentions increased in both studies (p<.05). Worry about the harms of smoking increased in Pilot Study 1 (p=.01) but not in Pilot Study 2. Knowledge and perceived likelihood of harm increased in Pilot Study 2 (p<.05), but not in Pilot Study 1. The two-week outcomes for Pilot Study 2 showed the same pattern as the four-week outcomes (data not shown), except for cigarettes smoked per day which dropped from baseline (mean=9.10, SD=6.81, p=.02).

Table 3.

Changes in outcomes

| Pilot Study 1 (n=30) | Pilot Study 2 (n=46) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2-week follow-up | Baseline | 4-week follow-up | |||

| mean (SD) | mean (SD) | p | mean (SD) | mean (SD) | p | |

|

|

||||||

| Knowledge of smoking health risks | 2.47 (0.82) | 2.63 (0.72) | .17 | 2.67 (0.73) | 2.93 (0.44) | <.01* |

| Perceived likelihood of harm | 2.93 (0.12) | 3.10 (1.30) | .39 | 3.20 (1.09) | 3.59 (1.13) | .02* |

| Worry | 2.86 (1.06) | 3.38 (1.08) | .01* | 3.02 (1.00) | 3.09 (1.05) | .42 |

| Subjective norms | 4.07 (0.95) | 4.16 (0.87) | .69 | 4.30 (0.83) | 4.42 (0.77) | .19 |

| Smoker prototypes – positive | 2.14 (1.07) | 1.88 (0.92) | .03* | 1.98 (0.83) | 1.47 (0.60) | <.01* |

| Smoker prototypes – negative | 1.93 (0.86) | 1.83 (0.85) | .15 | 1.68 (0.60) | 1.73 (0.97) | .76 |

| Self-efficacy | 3.27 (0.96) | 3.53 (0.81) | .10 | 3.46 (0.99) | 3.73 (1.03) | .06 |

| Quit intentions | 2.52 (1.06) | 2.89 (1.10) | .04* | 2.26 (0.97) | 2.93 (1.19) | <.01* |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 11.59 (9.31) | 11.58 (9.78) | .99 | 11.11 (7.44) | 9.98 (8.29) | .24 |

p<.05

The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day did not change between baseline and follow-up in either study. Ten percent of Pilot Study 1 participants and 20% of Pilot Study 2 participants stopped smoking for at least 24 hours during the study. No participants successfully quit smoking during Pilot Study 1. During Pilot Study 2, two participants had quit smoking by week 2 but they resumed by week 4, and one participant quit between weeks 2 and 4.

Process measures

Retention was very high in both studies (100% in Pilot Study 1 and 96% in Pilot Study 2). Nearly all participants said that they would probably or definitely participate in the study again, and 100% said they would probably or definitely recommend the study to a friend (Figure 2). Most smokers (90% in Pilot Study 1 and 78% in Pilot Study 2) found participating in this study to be easy or very easy.

About a third (11/30) of Pilot Study 1 smokers said in exit interviews that they thought the study was buying them cigarettes as our staff had prepaid them and escorted them to the store so they could buy cigarettes at the baseline interview. To address these concerns, we asked Pilot Study 2 participants to bring an eight-day supply of cigarettes with them to the study visits every week for four weeks. Most participants did not find this task to be burdensome: 15% of participants reported that it was difficult to bring in eight days’ worth of cigarettes, 30% said it was neither difficult nor easy, and 54% said it was easy or very easy.

DISCUSSION

Our proof of principle studies of placing warnings on real-world cigarette packages for an extended period of time suggests that our proposed protocol is feasible. The protocol had low attrition, high adherence, and allowed assessment of impact over time. Most smokers complied with the study protocol and reported high levels of satisfaction with the procedures. Thus, this new pack carrying protocol offers the potential for both experimental control and greater real-world dose than exposures in brief lab studies.

The original protocol (Pilot Study 1) provided a financial incentive immediately before the smoker purchased cigarettes because we were concerned that low-income smokers could not afford the up-front costs of buying two weeks’ worth of cigarettes at one time. However, we believe that our revised protocol (Pilot Study 2) may pose fewer risks to smokers. In the US, lower-income populations smoke at higher rates than their higher-income counterparts,[35] and, accordingly, research shows that most smokers do not purchase cigarettes in bulk, but rather by the pack.[36] Losing large numbers of smokers who cannot afford to purchase cigarettes in bulk would, in turn, limit the generalizability of cigarette pack labeling studies using such a protocol. However, many Pilot Study 1 participants believed that the study gave them free cigarettes, which could potentially increase smoking. Studies suggest lower prices encourage cigarette consumption.[37] Fortunately, cigarette consumption did not increase, while quit intentions did increase.

Another potential concern is whether having more cigarettes on hand might make participants smoke more, especially if they are not accustomed to purchasing packs in bulk. The empirical impact of stockpiling cigarettes on smoking behavior is unknown. Smokers can save money by purchasing cigarettes in bulk (e.g., cartons) rather than by the pack, but many smokers elect to ration their purchase quantities and impose additional transaction costs to limit their smoking.[38, 39] We suggest keeping the length of time between study appointments at one week, which will limit the number of cigarette packs that participants will have on-hand at one time, thus reducing the potential risk that participants will smoke more. Future research should try to assess unintended consequences of stockpiling packs.

Having participants bring their own cigarettes to study appointments decouples cigarette purchasing from receiving payment. Moreover, it appears that low-income smokers in our study were not deterred by having to purchase cigarettes in advance as part of the protocol as more than half of Pilot Study 2 participants were at or below 200% of the US federal poverty level. It remains possible that other low income smokers were unable to participate in the study.

Our findings point to a new pack labeling protocol with six steps: (1) schedule appointments one week apart; (2) determine daily cigarette consumption through smokers’ self-report; (3) ask smokers to purchase and bring to the study appointments the amount of cigarette packs they would normally smoke between appointments, with an extra supply to buffer against cancelations and allow for greater than expected use; (4) during study appointments, apply labels to smokers’ cigarette packs in-person by removing the top of the cellophane wrapping from the cigarette packs and applying self-adhesive labels with warnings directly to the packs, to prevent smokers from inadvertently removing the label with the wrapping; (5) provide study participation incentives at the end of the appointments and clearly communicate that the payment is for survey completion to reduce the possibility that participants will believe that the payments equate to receiving free cigarettes; and (6) refer smokers to cessation services at study completion or directly help smokers who want to quit. Table 4 gives the rationale for each protocol step. We implemented the six steps of this protocol successfully in Pilot Study 2.

Table 4.

Recommended pack labeling protocol for studies that place warnings on smokers’ cigarette packs

| Protocol Step | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Schedule appointments weekly | A week is feasible for smokers who would purchase cigarettes for the study, and it limits the number of cigarette packs a smoker has on hand. |

| 2. Determine cigarette consumption | Knowing how much a smoker typically smokes allows the researcher to instruct the smoker on how many packs to bring to the first and subsequent study visits. |

| 3. Ask smokers to purchase and bring cigarettes to study appointments | Asking smokers to purchase cigarettes on their own can help prevent smokers from thinking that the study is giving smokers “free cigarettes.” Asking them to bring extra packs allows for a buffer against missed appointments or in case they smoke more than expected in a given week. |

| 4. Apply labels to smokers’ cigarette packs. | Researchers label the packs, rather than smokers self-labeling packs, as self-labeling may serve as an active intervention. Also, researchers labeling packs is likely to lead to higher protocol compliance as compared to asking smokers to self-label their packs. |

| 5. Provide participation incentives for survey completion | Communicating that study incentives are for survey completion may reduce the possibility that participants will perceive that payments equate to receiving free cigarettes. |

| 6. Refer smokers to cessation services at study completion | Referral to cessation services may help smokers to quit at the end of the study, if they have not already. |

Strengths of the study include establishing the feasibility of a new pack labeling protocol in a field study with current smokers, followed over time. As we studied a convenience sample recruited in a single location, the generalizability of our findings remains to be established. By labeling cigarette packs that smokers were currently using, we tested novel warnings alongside the standard US text-only warnings that we did not obscure. Depending on the brand, the warnings may have covered some of the branding or color of the cigarette packs. In these cases, we may have overestimated the impact of the warning, as obscuring the branding may make cigarettes less appealing to smokers.[40, 41] We relied on self-report to measure protocol adherence, but the extent to which self-reported adherence reflects actual adherence is unknown. We tested only methods for labeling cigarette packs, and we are unable to determine the utility of this protocol for other tobacco products. Finally, the small sample size limited statistical power to detect changes in psychosocial and behavioral outcomes.

Given the compelling need for better strategies to test the efficacy of warnings on tobacco products,[42, 43] this feasible protocol holds promise for improving our ability to determine the utility of warnings on cigarette packages. Our recommended protocol developed through this proof of principle study mimics real-world exposure to tobacco product packaging while allowing for experimental control needed in randomized trials. The protocol could be used to test the impact of other cigarette pack warning characteristics such as size and format, as well as the impact of modified-risk tobacco product warnings.[44, 45] Moreover, researchers can adapt the protocol to test graphic or text warnings for non-cigarette tobacco products. Future research should examine the utility of our pack labeling protocol in randomized controlled trials.

Rigorous evidence is required to identify the best ways to communicate the risks of tobacco use, de-normalize tobacco products, and reduce the extent to which tobacco product packaging glamorizes and promotes the deadly product inside. Our proof of principle studies provide a feasible strategy for testing warning messages that ensures high adherence, and can generate stronger evidence of the real-world impact of warnings on smoking-related outcomes.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

Experimental studies on graphic cigarette pack warnings typically use a brief one-time exposure, often in a laboratory setting. Naturalistic pack labeling studies hold promise for replicating the frequency and duration of warning exposure in the real world while maintaining experimental control. We developed and tested a six-step protocol for labeling smokers’ actual cigarette packs. The protocol was feasible to implement, was acceptable to smokers, and had high retention over four weeks. Using the protocol can yield stronger evidence on the impact of warnings to better inform the development of cigarette pack warning policies around the world.

Acknowledgments

We thank the research participants for taking part in this study. Our thanks and appreciation to Katie Byerly for her help with participant recruiting and data collection.

FUNDING

This work was supported by 4CNC: Moving Evidence into Action grant number U48/DP001944, and by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grant numbers U01 CA154281 and P30 CA016086-38S2.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTORS

KMR and NTB originated the study. MGH drafted the manuscript. JGLL and MGH implemented the protocols and conducted statistical analyses. KMR, MGH, SMN, and NTB developed the measures and protocols. KP assisted with analysis and writing, and edited multiple drafts of the paper. All authors provided critical feedback on drafts of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None declared.

References

- 1.Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):147–153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotnowski K, Hammond D. The impact of cigarette pack shape, size and opening: evidence from tobacco company documents. Addiction. 2013 doi: 10.1111/add.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moodie C, Hastings G. Tobacco packaging as promotion. Tob Control. 2010;19(2):168–170. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.033449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health warnings on tobacco products – worldwide, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(19):528–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Warning about the dangers of tobacco. World Health Organization, Research for International Tobacco Control; 2011. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N, et al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: Findings from the ITC Four – Country survey. Addiction. 2009;104(4):669–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, et al. Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour. Tob Control. 2003;12(4):391–395. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azagba S, Sharaf MF. The effect of graphic cigarette warning labels on smoking behavior: Evidence from the Canadian experience. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GT. Cigarette graphic warning labels and smoking prevalence in Canada: a critical examination and reformulation of the FDA regulatory impact analysis. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 1):i7–12. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kees J, Burton S, Andrews JC, et al. Understanding how graphic pictorial warnings work on cigarette packaging. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 2010;29(2):265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantrell J, Vallone DM, Thrasher JF, et al. Impact of tobacco-related health warning labels across socioeconomic, race and ethnic groups: Results from a randomized web-based experiment. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P, et al. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fathelrahman AI, Omar M, Awang R, et al. Impact of the new Malaysian cigarette pack warnings on smokers’ awareness of health risks and interest in quitting smoking. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2010;7(11):4089–4099. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7114089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kees J, Burton S, Andrews JC, et al. Tests of graphic visuals and cigarette package warning combinations: implications for the framework convention on tobacco control. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. 2006;25(2):212. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thrasher JF, Rousu MC, Anaya-Ocampo R, et al. Estimating the impact of different cigarette package warning label policies: The auction method. Addict Behav. 2007;32(12):2916–2925. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thrasher JF, Rousu MC, Hammond D, et al. Estimating the impact of pictorial health warnings and “plain” cigarette packaging: Evidence from experimental auctions among adult smokers in the United States. Health Policy. 2011;102(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillán E, Villalobos V, et al. Can pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages address smoking-related health disparities? Field experiments in Mexico to assess pictorial warning label content. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9899-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thrasher JF, Carpenter MJ, Andrews JO, et al. Cigarette warning label policy alternatives and smoking-related health disparities. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(6):590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moodie C, Mackintosh AM, Hastings G, et al. Young adult smokers’ perceptions of plain packaging: a pilot naturalistic study. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):367–373. doi: 10.1136/tc.2011.042911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie D, Etter JF. Utilization and impact of cigarette pack covers illustrated with antismoking messages. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(2):107–118. doi: 10.1177/0163278704264050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters E, Romer D, Evans A. Reactive and thoughtful processing of graphic warnings: Multiple roles for affect. University of North Carolina, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Center for Regulatory Research on Tobacco Communication; Chapel Hill, NC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mays D, Murphy SE, Johnson AC, et al. A pilot study of research methods for determining the impact of pictorial cigarette warning labels among smokers. Tob Induc Dis. 2014;12(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McQueen A, Caburnay C, Kaphingst K, et al. What are the reactions of diverse US smokers when graphic warning labels are affixed to their cigarette packs?; American Society of Preventive Oncology Conference; Memphis, TN. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraemer JD, Baig SA. Analysis of legal and scientific issues in court challenges to graphic tobacco warnings. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(3):334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. SAGE Publications, Incorporated; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. GATS (Global Adult Tobacco Survey) 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepper JK, Reiter PL, McRee AL, et al. Adolescent males’ awareness of and willingness to try electronic cigarettes. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. Surveys. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armitage CJ. Efficacy of a brief worksite intervention to reduce smoking: the roles of behavioral and implementation intentions. J Occup Health Psychol. 2007;12(4):376–390. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCool J, Cameron L, Petrie K. Stereotyping the smoker: adolescents’ appraisals of smokers in film. Tob Control. 2004;13(3):308–314. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCool J, Cameron LD, Robinson E. Do parents have any influence over how young people appraise tobacco images in the media? J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pepper JK, Cameron LD, Reiter PL, et al. Non-smoking male adolescents’ reactions to cigarette warnings. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e65533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein WM, Zajac LE, Monin MM. Worry as a moderator of the association between risk perceptions and quitting intentions in young adult and adult smokers. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(3):256–261. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nonnemaker J, Farrelly M, Kamyab K, et al. Experimental study of graphic cigarette warning labels: Final results report. Prepared for Center for Tobacco Products, Food and Drug Administration. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2011. MMWRMorbidity and mortality weekly report. 2012;61(44):889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emery S, White MM, Gilpin EA, et al. Was there significant tax evasion after the 1999 50 cent per pack cigarette tax increase in California? Tob Control. 2002;11(2):130–134. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson LM, Avila Tang E, Chander G, et al. Impact of tobacco control interventions on smoking initiation, cessation, and prevalence: a systematic review. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:961724. doi: 10.1155/2012/961724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wertenbroch K. Consumption self-control by rationing purchase quantities of virtue and vice. Marketing Science. 1998;17(4):317–337. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khwaja A, Silverman D, Sloan F. Time preference, time discounting, and smoking decisions. J Health Econ. 2007;26(5):927–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakefield MA, Germain D, Durkin SJ. How does increasingly plainer cigarette packaging influence adult smokers’ perceptions about brand image? An experimental study. Tob Control. 2008;17(6):416–421. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.026732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wakefield MA, Hayes L, Durkin S, et al. Introduction effects of the Australian plain packaging policy on adult smokers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2013;3(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayer R, Johns D, Colgrove J. The FDA and Graphic Cigarette-Pack Warnings – Thwarted by the Courts. N Engl J Med. 2013 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, et al. The impact of graphic cigarette pack warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies; Sixty-fourth Annual Conference of the International Communication Association; Seattle, WA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Connor RJ. Postmarketing surveillance for “modified-risk” tobacco products. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(1):29–42. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deyton L, Sharfstein J, Hamburg M. Tobacco product regulation—a public health approach. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(19):1753–1756. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1004152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]