Abstract

Introduction

Systemic hyperfibrinolysis (accelerated clot degradation) and fibrinolysis shutdown (impaired clot degradation) are associated with increased mortality compared to physiologic fibrinolysis following trauma. Animal models have not reproduced these changes. We hypothesize rodents have a shutdown phenotype that require an exogenous profibrinolytic to differentiate mechanisms that promote or inhibit fibrinolysis.

Methods

Fibrinolysis resistance was assessed by thrombelastography (TEG) using exogenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) titrations in whole blood. There were three experimental groups: 1)tissue injury (laparotomy/bowel crush), 2)shock (hemorrhage to mean arterial pressure 20 mmHg), and 3)control (arterial cannulation and tracheostomy). Baseline and 30-minute post-intervention blood samples were collected, and assayed with TEG challenged with taurocholic acid (TUCA).

Results

Rats were resistant to exogenous tPA; CL30 (Percent clot remaining 30 minutes after maximum amplitude) at 150ng/ml (p=0.511) and 300ng/ml (p=0.931) was similar to baseline, while 600ng/ml (p=0.046) provoked fibrinolysis. Using the TUCA challenge, the percent change in CL30 from baseline was increased in tissue injury compared to control (p=0.048.), whereas CL30 decreased in shock versus control (p=0.048). TPA increased in the shock group compared to tissue injury (p=0.009) and control (p=0.012).

Conclusion

Rats have an innate fibrinolysis shutdown phenotype. The TEG TUCA challenge is capable of differentiating changes in clot stability with rats undergoing different procedures. Tissue injury inhibits fibrinolysis while shock promotes tPA-mediated fibrinolysis.

Introduction

One in four patients with severe injury experience changes in coagulation within 30 minutes of injury, which is associated with a 5-fold risk of mortality(1). Coagulation derangements after trauma have been reported to have two predominant components: 1) impairment of blood clot formation (hypocoagulation), and 2) increased rate of clot degradation (hyperfibrinolysis) (2). These coagulation changes in animal experiments were originally attributed to a combination of tissue injury and hemorrhagic shock. Animal models attempting to recreate trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) have been able to demonstrate impaired clot formation(3-6), but have not been able to replicate the increased levels of clot degradation (systemic hyperfibrinolysis) seen in humans with TIC.

As the study of postinjury coagulopathy has intensified, hypocoagulation and hyperfibrinolysis appear mechanistically distinct. Principal component analyses suggest that hyperfibrinolysis does not correlate with impaired clot formation (7, 8). In a human study, patients with non-traumatic cardiac arrest had a high prevalence of hyperfibrinolysis (9). Although significant hypotension in injured patients is associated with hyperfibrinolysis, there is no correlation with injury severity (ISS) (10). Rodents may have an inherent resistance to fibrinolysis, which would explain failure to reproduce changes in clot degradation in animal models. To reduce resistance of fibrinolysis, a novel assay was developed that challenged the stability of whole blood with taurocholic acid (TUCA), a known pro-fibrinolytic agent (11). We hypothesize that shock promotes fibrinolysis, and that tissue injury has an inhibitory effect that can be differentiated using a modified TEG technique challenging whole blood with TUCA.

Methods

Subjects

The University of Colorado Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved this animal study under protocol #90814. Male Sprague Dawley rats (n=27) ages 14-16 weeks with weights between 350 and 400 grams were used for the experiment. Female rodents were not used due to their reported differences in immune-inflammatory responses to injury. In addition, males were selected due to this gender being more prevalent in severely injured human trauma patients, and an appropriate subject for an initial approach to identify regulators of fibrinolysis.

Animal Induction and Cannulation

Anesthesia was induced with pentobarbital (5mg/kg, intraperitoneal) followed by tracheostomy and femoral artery cannulation. The femoral artery cannula was used for invasive measurement of blood pressure, and for blood withdrawal for controlled hemorrhage and sampling. The animals were allowed to recover from these initial procedures for airway and vascular access, and then randomized into one of the three groups (Control, Shock, and Tissue Injury), as described below.

Stage II Hemorrhagic Shock and Mild Tissue Injury (Control)

Mild tissue injury from tracheotomy and femoral artery cannulation was performed. A 2 ml baseline blood sample was drawn through the femoral artery. This quantity of blood was required for multiple thrombelastography (TEG) assays and for plasma protein analysis. The animal was observed for 30 minutes before a second (final) blood draw was performed (2 ml). The total blood obtained for assays was approximately 15% of the total estimated blood volume and representative of stage II shock (12).

Stage IV Hemorrhagic Shock and Mild Tissue Injury (Shock)

Mild tissue injury (from tracheotomy and femoral artery cannulation) is described above. After baseline blood draw (2 ml), the animal was sequentially hemorrhaged with 0.5 -1 ml blood draws at 30-second intervals to obtain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 20 ± mmHg within 5 minutes. This pressure-driven procedure was designed to target a blood loss of greater than 40% EBV (representative of stage IV shock) based on an objective metric of shock severity (MAP). (12) Animals were kept at MAP of 20 (+/- 2) mmHg for 30 minutes. The 30-minute time frame was designed to replicate the clinical course (in terms of time from injury to arrival at the hospital) of a cohort of the most severely injured patients that undergo a resuscitative emergency department thoracotomy (median of 24 minutes and interquartile range from 20 – 30; data not published). This severe degree of shock was selected based on our prior work with rodents, which demonstrated that lesser degrees of hemorrhagic shock (MAP > 30 mmHg) did not result in changes in coagulation (13). Additional blood was removed during the 30 minutes of shock if the MAP exceeded 25 mmHg. At the end of 30 minutes, a final blood draw of 2ml was obtained.

Stage II Shock and Major Tissue Injury (Tissue Injury)

Tracheotomy and femoral artery cannulation were performed as described above. Baseline blood samples were obtained as described above, followed by a midline incision of the abdomen. After evisceration, a 10-cm section of small intestine was isolated proximal to the cecum and run gently through a clamp covered with silastic tubing in order to cause a mild crush injury. The intestines were returned to the peritoneal cavity, and the abdominal incision closed. Intestinal injury was employed because of previous data demonstrating that post-injury mesenteric lymph drives remote multiple organ failure (MOF) (14). This injury type could reasonably promote impairment of fibrinolysis, as it has been observed that MOF is associated with fibrinolysis shutdown (15). Following 30 minutes of observation, a final blood draw was performed (2ml).

Blood Samples and Rodent Thrombelastography

Whole blood was collected in 3.2 % sodium citrate tubes at a 1:10 ratio, based on a standardized model of performing TEG in rodents (16). Individual microcentrifuge tubes were prefilled with citrate and marked to an appropriate fill level to ensure reproducible ratios of whole blood to citrate. Citrated native thrombelastography assays were re-calcified and run according to the manufacturer's instructions on a TEG 5000 Thrombelastography Hemostasis Analyzer (Haemonetics, Niles IL). The CL30 parameter was used to quantify fibrinolysis. This variable corresponds to the percent of clot strength remaining 30 minutes after reaching maximum amplitude. Blood not used for TEG was spun to yield plasma for protein analysis. Whole blood was centrifuged at 6,000 g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Plasma was removed and then spun at 12,500 g for 10 minutes at the same temperature to remove contaminating platelets and acellular debris. The remaining plasma was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until it was analyzed.

Tissue Plasminogen Activator

Human single-chain tPA from Molecular Innovation (Novi, MI) was diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate buffered saline to a final concentration of 10 microgram per microliter. Individual aliquots of tPA were stored at -80 °C and thawed immediately prior to use.

tPA Challenge

Prior work with tPA has identified that an exogenous tPA mixed at a concentration of 75 ng/ml increases TEG-detectable fibrinolysis in whole blood from healthy human volunteers (data not shown). Our method of adding exogenous tPA to whole blood for assessment of resistance to fibrinolysis has been described previously(17). Non-shocked rat whole blood (n=6) was contrasted with and without tPA with incremental increases up to a supra-physiologic concentration of 600 ng/mL.

Taurocholic Acid (TUCA)

Lyophilized taurocholic acid purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Product # 86993, St. Louis, MO) was reconstituted to 0.125 M in normal saline. Aliquots of 40 μL of this solution were stored at 4 °C. TUCA is an effective pro-fibrinolytic molecule (11). Since rats require a supra-physiologic level of tPA to increase fibrinolysis at baseline, TUCA was used as an alternative to promote fibrinolysis.

TUCA Challenge

Prior to performing TEG, 1 or 3 μL of TUCA was mixed exogenously with 400 μL of whole blood. These two concentrations were selected to produce a baseline CL30 between 90 and 70% (i.e. 10 -30% lysis), and allowed for quantification of an increase, as well as a decrease in fibrinolysis. A CL30 less than this range would be limited in detecting enhancement of fibrinolysis, and a CL30 greater than this range would be limited for detecting resistance of fibrinolysis. Animals with a baseline sample that did not achieve a CL30 within this range with either dose of TUCA were excluded. Samples with TUCA doses were run in parallel with a whole blood sample that had no additional exogenous reagents added.

ELISA

Assays for detection of plasma tissue levels of tPA and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) were purchased from Molecular Innovations (Novi, MI product #RPAIKT-TOT and RTPAKT-TOT). Plasma and tissue homogenate supernatants were used in a 1:1 dilution, and were run according to the manufacture's recommendations. Samples were run in duplicate and the average of two samples was used for quantification. Using the “ladder” of standards, standard curves were constructed, and plasma levels were quantified in ng/ml after adjusting for dilution. Additional post hoc circulating proteins assays were performed to further characterize systemic fibrinolytic activity. Assays for plasminogen, fibrin degradation products (FDP), and angiostatin were purchased from My Biosource (San Diego, CA: Product #MBS008728, MBS733501, MBS707116).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis. A power analysis determined that a total sample of 27 animals (9 per arm) allowed for the detection of a difference of approximately 15% or larger in CL30 with 80% power and 95% confidence assuming conservative estimates of baseline CL30 80% IQR 70-90. All experimental results were represented as the group median, and variability was represented by interquartile range (IQR), as several variables were not normally distributed (e.g., CL30, tPA levels). Experimental groups were made with the Kruskal-Wallis test, with a step-wise adjustment performed on post hoc pairwise comparisons. Statistical significance was set at an alpha of 0.05.

Results

Physiologic Response to Interventions

Rodents had similar baseline blood pressure (p=0.498) and decrease in blood pressure after first blood draw (p=0.963, Figure 1). Thirty minutes after the experimental procedure, the shock group had significantly lower blood pressure than control and tissue injury (p<0.001 for both), but not significant between control and tissue injury (p=0.549). The percent of estimated blood volume was larger in the shock group 55.5% (IQR 53.0-60.0 p<0.001 vs tissue injury and p=0.007 vs control) compared to the control (22.1% IQR 18.3-22.5) and tissue injury (19.0% IQR 17.7-21.4 p=0.814 vs control).

Figure 1. Physiologic Response to Interventions.

Error bars =95% confidence intervals

Y axis represents the mean arterial pressure in mmHg. X axis represents time points at which blood pressure was measured. Animals in all experimental arms experienced a decrease in blood pressure after first blood samples. Those animals not in the hemorrhagic shock recovered from this transient blood loss over the following 30 minutes of observation.

Rodent Resistance to Tissue Plasminogen Activator

Baseline CL30 in rodents had a median value of 98.2% (IQR 98.1-100%). Exogenous administration of tPA to rat whole blood at doses of 150 and 300 ng/ml yielded CL30 values of 99.3% (98.1 to 100%) and 98.7% (98.3 to 99.0%) respectively, which were not significantly different from baseline (p=0.551 and p=0.931, respectively). Only the highest concentration of tPA (600ng/ml) significantly reduced CL30 (96.3% IQR 77.4 to 96.6% p=0.046) compared to baseline (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Rodent Whole Blood is Resistant to TPA Mediated Fibrinolysis.

*= P<0.05 compared to whole blood

Y axis represents the CL30 (percent of remaining clot strength 30 minutes after reaching maximum amplitude). On the X axis represents increasing concentrations of tissue plasminogen activator to exogenously mixed to non shocked rat whole blood.

Native TEG versus TUCA challenge

CL30 percent change from baseline was not different between any of the experimental arms (p=0.202, Figure 3). Specifically, CL30 percent change from baseline was -0.30% (IQR-0.65 to 2.1) for control, -1.11% (IQR -2.93 to 0.10) it the shock group, and -0.61% (IQR -1.65 to 1.52) in the tissue injury group. Conversely, CL30 percent change from baseline was significantly different between the experimental arms after exogenous challenge of TUCA (p<0.001, Figure 4). Compared to the control group (CL30 percent change -27.4%, IQR -51.3 to -24.9), CL30 percent change with TUCA challenge was significantly lower in the shock arm (-81.4% IQR-89.3to -75.0 p=0.048), but significantly higher in the tissue injury arm (16.6% IQR 3.4 to 32.2 p=0.048).

Figure 3. Native TEG does not Discriminate Tissue Injury from Shock.

The Y axis represents the percent change in CL30 from baseline to post procedure. The X axis represents different experimental arms. The control group by the end of the experiment had stage II shock and mild tissue injury, the shock group by the end of the experiment had stage IV shock and mild tissue injury, and the tissue injury group had major tissue injury and stage II shock.

Figure 4. TUCA Challenge TEG Discriminates Tissue Injury from Shock.

*=P<0.05 compared to control

**=P<0.05 compared to shock

The Y axis represents the percent change in CL30 from baseline to post procedure. The X axis represents different experimental arms. The control group by the end of the experiment had stage II shock and mild tissue injury, the shock group by the end of the experiment had stage IV shock and mild tissue injury, and the tissue injury group had major tissue injury and stage II shock.

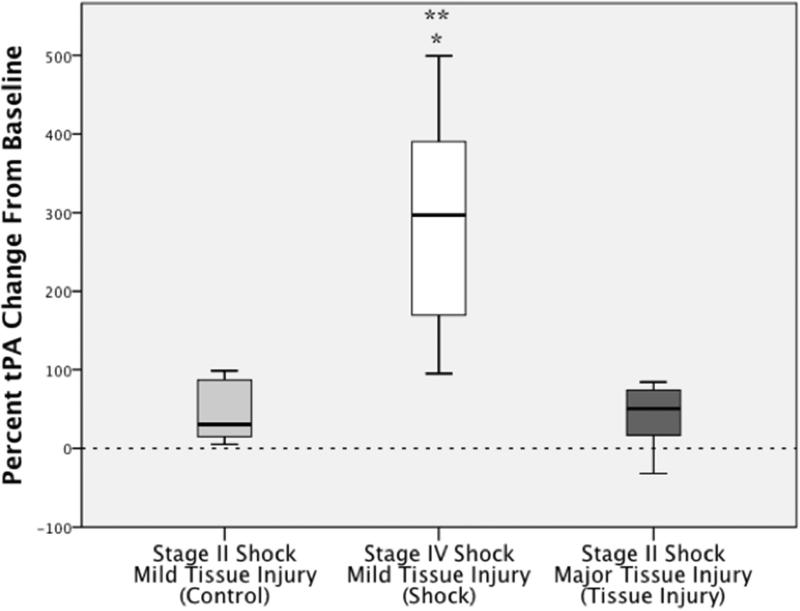

Shock, but not Tissue Injury, Increases Tissue Plasminogen Activator

The percent change in tPA levels from baseline to post intervention differed between experimental arms (p=0.005) (Figure 5). The shock group had a significant increase in tPA (296%, IQR 151 to 417%) compared to control (30%, IQR 13 to 90% p=0.017) and trauma (51%, IQR 5 to 77 p=0.011). Change in tPA from baseline to post intervention did not differ between trauma and control (p=1.00). PAI-1 levels were undetectable in all plasma samples. Changes in additional proteins related to fibrinolysis are listed in Table 1. Circulating FDPs were never elevated between experimental arms, which are consistent with results from native TEG. Of interest, plasminogen was depleted following both shock and tissue injury compared to control. Angiostatin, a marker of inflammatory degradation of plasminogen, was reduced in the shock group compared to the tissue injury group.

Figure 5. tPA Levels Increase After Shock not Tissue Injury.

*=P<0.05 compared to control

**=P<0.05 compared to shock

The Y axis represents the percent change in tissue plasminogen activator from baseline to post procedure. The X axis represents different experimental arms. The control group by the end of the experiment had stage II shock and mild tissue injury, the shock group by the end of the experiment had stage IV shock and mild tissue injury, and the tissue injury group had major tissue injury and stage II shock.

Table 1.

Fibrinolysis Protein Analysis

| tPA (ng/ml) | PLG (μg/ml) | FDP (ng/ml) | Angiostatin (pg/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | p=0.432 | p=0.738 | p=0.007 | p=0.029 |

| Sham | 5.8 (5.2-6.1) | 281 (225-335) | 20 (15-28) | 210 (196-302) |

| Shock | 6.0 (5.2-7.4) | 281 (250-346) | 36 (26-43) | 374 (307-398) |

| Tissue Injury | 5.0 (4.4-6.4) | 277 (237-300) | 45(38-51) | 401 (365-472) |

| Post Procedure | p=0.003 | p=0.039 | p=0.041 | p=0.018 |

| Sham | 7.3 (6.8-8.85) | 252 (220-293) | 25 (14-40) | 243 (131-289) |

| Shock | 21.1(16.4-34.5) | 172 (163-228) | 30 (10-39) | 239 (157-312) |

| Tissue Injury | 7.8 (5.5-9.0) | 215 (200-226) | 51 (36-52) | 426 (319-466) |

| Percent Change | p=0.005 | p=0.064 | p=0.137 | p=0.056 |

| Sham | 30% (13% to 90%) | 0% (−27% to 9%) | −17% (−60% to −11%) | −17 (−27% to 0%) |

| Shock | 297% (150% to 417%) | −32% (−50% to −20%) | −14% (−23 to 25%) | −34 (−58% to −20%) |

| Tissue Injury | 51% (5%-77%) | −23 (−34% to −7%) | −7% (−29% to 75%) | 0% (−11%-10%) |

Table one represents the quantification of proteins related to fibrinolysis analyzed in this study. Baseline and post procedure measurements are represented for all experimental arms. Because of baseline variability in many of these proteins, the last four rows represent the percent change in proteins from baseline to post intervention to adjust for animal-to-animal variability.

Discussion

Rats are resistant to tPA mediated fibrinolysis, rendering TEG insensitive to detect changes in the fibrinolytic system during shock and tissue injury. Exogenous challenge of rodent blood with a potent pro-fibrinolytic agent results in increased susceptibility to clot degradation, with whole blood from shocked animals having increased susceptibility to fibrinolysis compared to that from animals with tissue injury but no shock; supporting the hypothesis that shock increases fibrinolysis while tissue injury impairs it. This phenomena correlates with a marked increase in plasma tPA concentrations after shock (Figure 5), compared to a lesser increase of tPA with control and tissue injury. These differences in clot degradation between experimental arms. However it does not appear to be attributable to PAI-1 plasma levels, which were undetectable in all three groups.

Since the original work that demonstrated postinjury coagulopathy was increased by the additive effects of injury severity and shock(18), it has become dogma that an animal coagulopathy model requires both tissue injury and shock. In a review by Frith et al(19), 23 animal models were identified to assess coagulation changes related to trauma. Prior to 2009, 38% of these studies used a combination of tissue injury and shock, and subsequently 86% used a combination. The most recent rat model from the military entails polysystem trauma with tissue injury to muscle, bone, bowel, and liver in combination with major hemorrhage (6). Without a clear understanding of what drives changes in fibrinolysis, increasing the amount and type of tissue injury is problematic when evaluating the phenotypic changes of fibrinolysis related to TIC.

Appreciation that the two components of TIC (hypocoagubility and hyperfibrinolysis) are not necessarily linked (7, 8) warrants a re-evaluation of how to design animal models with the objective of identifying specific TIC phenotypes. We found that tissue injury and shock have opposing actions on clot stability. This change in clot stability in a pro-fibrinolytic environment occurred at 30 minutes. Recently, it has been appreciated that trauma patients presenting to the hospital with hyperfibrinolysis detected by TEG have elevated tPA levels (20). These investigators found a correlation to low systolic blood pressure and hyperfibrinolysis and elevated tPA, which is consistent with existing literature that hypoperfusion promotes fibrinolysis in trauma patients (10) and in patients without injury (9). Our model supports that hemorrhagic shock, but not tissue injury, promotes fibrinolysis through a tPA mediated mechanism. This is further supported by both control and tissue injury rats also having an increase in tPA levels by the end of the experiment in which greater than 15% of EBV was removed. However, there is evidence of effect modification of tissue injury increasing clot stability in the presences of TUCA compared to control.

We had anticipated that the inhibitor of tPA, PAI-1, would be elevated after tissue injury and explain the observed resistance to TUCA in this arm; however, because PAI-1 levels were below the detection threshold of our assay, we were unable to draw conclusions regarding this proposed mechanism. In this model, tissue levels of PAI-1 were identified in multiple organs suggesting the assay is valid (data not published). Nevertheless, rats are markedly resistant to tPA at baseline, and it is likely that other unmeasured regulators of fibrinolysis are present. TUCA has been shown to augment tPA mediated fibrinolysis (11) but also has been shown to impair platelet function (21). Platelets have been proposed to provide a protective shell to a central fibrin clot, and support the clot by release of pro-coagulants and anti-fibrinolytics during degranulation (22). Tissue injury, therefore, has the potential to increase platelet activity and promote resistance to fibrinolysis, while shock, causing acidosis, previously shown to impair platelets (23), promotes hyperfibrinolysis. Rodents have significantly more platelets than humans (24), and increased platelet activity is a likely candidate to explain their baseline resistance to fibrinolysis, which can be overcome with a metabolite that has both antiplatelet and pro-fibrinolytic properties. In our post hoc proteins analysis we identified that a circulating degradation product of plasminogen by neutrophil related proteases, angiostatin (25), was decreased following shock, but remained stable after tissue injury, despite plasminogen levels decreasing in both experimental arms post-intervention. Angiostatin is a potent anti-angiogenic protein and has the potential to play a role in fibrinolysis regulation. While this study was designed to identify this association of inflammation and coagulation regulation, these observations warrant future investigation.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that a pro-fibrinolytic challenge of rat whole blood identifies differences in clot stability following three distinct trauma patterns (mild tissue injury, major tissue injury, and shock). The San Francisco group who developed the original TIC mouse model did not find changes in coagulation with hemorrhage or shock alone when using standard assays (3) as we also appreciated with using conventional TEG. While our results cannot conclusively determine that tissue injury inhibits tPA mediated fibrinolysis using conventional assays, we have demonstrated that shock increases tPA and promotes clot instability in the presence of TUCA, while tissue injury has the opposite effect. Further work is warranted to evaluate other tissue specific injury patterns and their effect on fibrinolysis, in addition to establishing a mechanism for TUCA resistant fibrinolysis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants: T32-GM008315, P50-GM049222 1, and UM-1HL120877. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS, NHLBI or National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the 10th Annual Academic Surgical Congress in Las Vegas, NV, February 3-5, 2015

References

- 1.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Schultz MJ, Levi M, Mackersie RC, et al. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: hypoperfusion induces systemic anticoagulation and hyperfibrinolysis. The Journal of trauma. 2008;64(5):1211–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318169cd3c. discussion 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, Matthay MA, Mackersie RC, Pittet JF. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Annals of surgery. 2007;245(5):812–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000256862.79374.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesebro BB, Rahn P, Carles M, Esmon CT, Xu J, Brohi K, et al. Increase in activated protein C mediates acute traumatic coagulopathy in mice. Shock. 2009;32(6):659–65. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a5a632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sillesen M, Rasmussen LS, Jin G, Jepsen CH, Imam A, Hwabejire JO, et al. Assessment of coagulopathy, endothelial injury, and inflammation after traumatic brain injury and hemorrhage in a porcine model. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2014;76(1):12–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aaa675. discussion 9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho SD, Holcomb JB, Tieu BH, Englehart MS, Morris MS, Karahan ZA, et al. Reproducibility of an animal model simulating complex combat-related injury in a multiple-institution format. Shock. 2009;31(1):87–96. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181777ffb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darlington DN, Craig T, Gonzales MD, Schwacha MG, Cap AP, Dubick MA. Acute coagulopathy of trauma in the rat. Shock. 2013;39(5):440–6. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31829040e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutcher ME, Ferguson AR, Cohen MJ. A principal component analysis of coagulation after trauma. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2013;74(5):1223–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31828b7fa1. discussion 9-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin TL, Moore EE, Moore HB, Gonzalez E, Chapman MP, Stringham JR, et al. A principal component analysis of postinjury viscoelastic assays: Clotting factor depletion versus fibrinolysis. Surgery. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schochl H, Cadamuro J, Seidl S, Franz A, Solomon C, Schlimp CJ, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis is common in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: results from a prospective observational thromboelastometry study. Resuscitation. 2013;84(4):454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore HB, Moore EE, Gonzalez E, Chapman MP, Chin TL, Silliman CC, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis, physiologic fibrinolysis, and fibrinolysis shutdown: the spectrum of postinjury fibrinolysis and relevance to antifibrinolytic therapy. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2014;77(6):811–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000341. discussion 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonstra EA, Adelmeijer J, Verkade HJ, de Boer MT, Porte RJ, Lisman T. Fibrinolytic proteins in human bile accelerate lysis of plasma clots and induce breakdown of fibrin sealants. Annals of surgery. 2012;256(2):306–12. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824f9e7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collicott PE. Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS): past, present, future--16th Stone Lecture, American Trauma Society. The Journal of trauma. 1992;33(5):749–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wohlauer MV, Moore EE, Droz NM, Harr J, Gonzalez E, Fragoso M, et al. Hemodilution is not critical in the pathogenesis of the acute coagulopathy of trauma. The Journal of surgical research. 2012;173(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stringham JR, Moore EE, Gamboni F, Harr JN, Fragoso M, Chin TL, et al. Mesenteric lymph diversion abrogates 5-lipoxygenase activation in the kidney following trauma and hemorrhagic shock. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2014;76(5):1214–21. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardaway RM, Harke H, Tyroch AH, Williams CH, Vazquez Y, Krause GF. Treatment of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a final report on a phase I study. The American surgeon. 2001;67(4):377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wohlauer MV, Moore EE, Harr J, Gonzalez E, Fragoso M, Silliman CC. A standardized technique for performing thromboelastography in rodents. Shock. 2011;36(5):524–6. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31822dc518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore HB, Moore EE, Gonzalez E, Hansen KC, Dzieciatkowska M, Chapman MP, et al. Hemolysis Exacerbates Hyperfibrinolysis While Platelolysis Shuts Down Fibrinolysis: Evolving Concepts of the Spectrum of Fibrinolysis in Response to Severe Injury. Shock. 2014 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brohi K, Singh J, Heron M, Coats T. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. The Journal of trauma. 2003;54(6):1127–30. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000069184.82147.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frith D, Cohen MJ, Brohi K. Animal models of trauma-induced coagulopathy. Thrombosis research. 2012;129(5):551–6. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardenas JC, Matijevic N, Baer LA, Holcomb JB, Cotton BA, Wade CE. Elevated tissue plasminogen activator and reduced plasminogen activator inhibitor promote hyperfibrinolysis in trauma patients. Shock. 2014;41(6):514–21. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiao YJ, Chen JC, Wang CN, Wang CT. The mode of action of primary bile salts on human platelets. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1993;1146(2):282–93. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brass LF, Stalker TJ. Minding the gaps--and the junctions, too. Circulation. 2012;125(20):2414–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.106377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Etulain J, Negrotto S, Carestia A, Pozner RG, Romaniuk MA, D'Atri LP, et al. Acidosis downregulates platelet haemostatic functions and promotes neutrophil proinflammatory responses mediated by platelets. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2012;107(1):99–110. doi: 10.1160/TH11-06-0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trowbridge EA, Martin JF, Slater DN, Kishk YT, Warren CW, Harley PJ, et al. The origin of platelet count and volume. Clinical physics and physiological measurement : an official journal of the Hospital Physicists' Association, Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Medizinische Physik and the European Federation of Organisations for Medical Physics. 1984;5(3):145–70. doi: 10.1088/0143-0815/5/3/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scapini P, Nesi L, Morini M, Tanghetti E, Belleri M, Noonan D, et al. Generation of biologically active angiostatin kringle 1-3 by activated human neutrophils. Journal of immunology. 2002;168(11):5798–804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]