Abstract

Objective

Co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use has become increasingly prevalent among young adults, but it is not clear how tobacco use may alter the neurocognitive profile typically observed among cannabis users. Although there is substantial evidence citing cannabis and tobacco's individual impact on episodic memory and related brain structures, few studies have examined the impact of combined cannabis and tobacco use on memory.

Method

This investigation examined relationships between amount of past year cannabis and tobacco use on four different indices of episodic memory among a sample of young adults who identified cannabis as their drug of choice.

Results

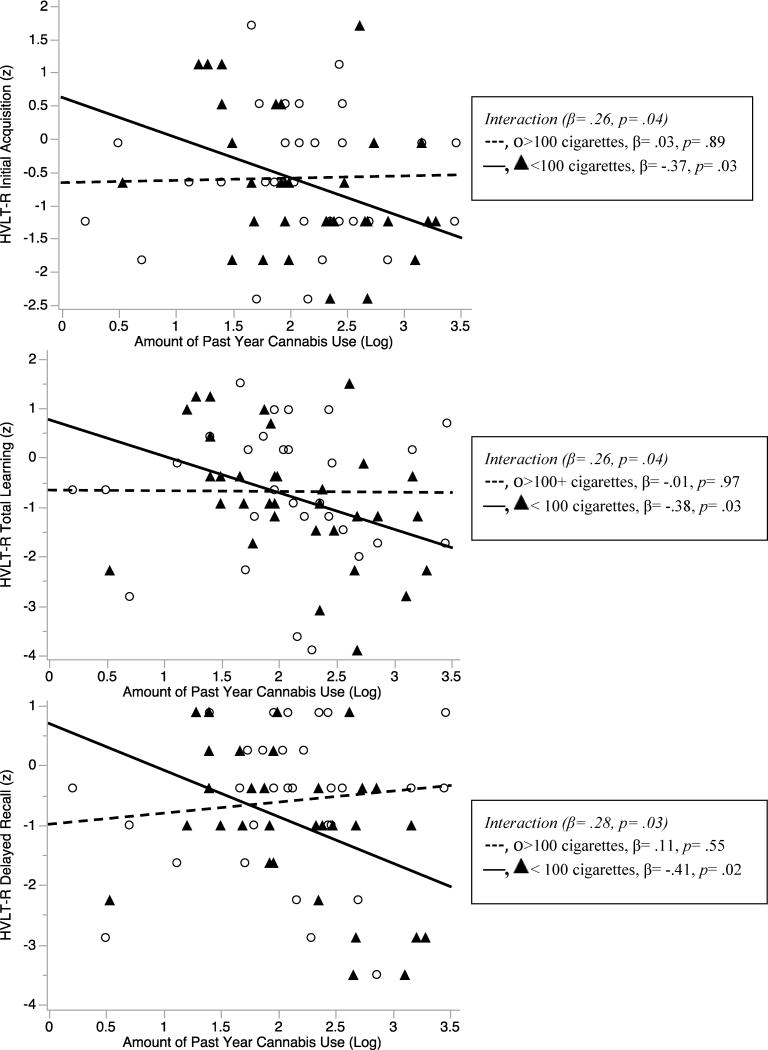

Results indicated that more cannabis use was linked with poorer initial acquisition, total learning and delayed recall on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test--Revised (HVLT-R), but only among cannabis users who sporadically smoked cigarettes in the past year. Conversely, amount of past year cannabis use was not associated with episodic memory performance among individuals who more consistently smoked cigarettes in the past year. These differences could not be explained by several relevant potential confounds.

Conclusions

These findings provide important insight into a potential mechanism (i.e., attenuation of cognitive decrements) that might reinforce use of both substances and hamper cessation attempts among cannabis users who also smoke cigarettes. Ongoing and future research will help to better understand how co-use of cannabis and tobacco impacts memory during acute intoxication and abstinence, and the stability of these associations over time.

Keywords: Cannabis, Nicotine, Episodic Memory, Young Adults, Neurocognition

Cannabis and tobacco are two of the most widely used drugs in the United States, with 48.6% and 48.1% of graduating high school students having ever used cannabis and tobacco respectively (CDC, 2013). Additionally, cannabis and tobacco use co-occur at high rates among young adults. For example, recent estimates suggest that nearly half of all young adults who smoked at least one cigarette in the past month also consumed cannabis (Ramo, Delucchi, Liu, Hall & Prochaska, 2014), which is nearly three times the rate observed in the general population (SAMHSA, 2012). These high rates of co-use are alarming given that concurrent cannabis and tobacco use is linked with more deleterious substance use outcomes than use of either drug alone (Peters, Budney, & Carroll, 2012). However, few studies have examined co-use of cannabis and tobacco on memory, despite evidence for each substance having an independent influence on episodic memory, as well as substantial data citing the impact of cannabis and tobacco on brain structures implicated in episodic memory (Heishman, Kleykamp, & Singleton, 2010; Viveros, Marco, & File, 2006). It is possible that tobacco may counteract some of the adverse neurocognitive effects of cannabis, which may encourage co-occurring use, serve as a barrier for quitting, and may therefore be associated with the maintained use of both substances. Thus, this investigation aims to better understand the relationship between cannabis and episodic memory in the context of tobacco use.

Independent effects of cannabis and tobacco on episodic memory are not surprising given that the primary psychoactive constituents of cannabis (i.e., Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol; Δ9-THC) and tobacco (i.e., nicotine) respectively target CB1 receptors and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which are densely populated in structures central to memory, namely the hippocampus (Mackie, 2005; Picciotto, Caldarone, King, & Zachariou, 2000). Further, there is mounting preclinical evidence pointing to functional interactions between cannabinoid and cholinergic systems in the hippocampus. For example, nicotine exposure results in region-dependent increases in CB1 expression and endocannabinoid levels in the hippocampus that persist for one month following nicotine cessation (Gonzalez et al., 2002; Marco et al., 2007). Emerging data also suggest that cannabinoid agonists produce increased efflux and decreased turnover of acetylcholine in memory-relevant structures including the hippocampus (Viveros et al., 2006).

The opposing effects that independent administrations of cannabis and tobacco have on episodic memory are well documented. Specifically, cannabis users show memory impairments that are related to cannabis use severity, resolve after 28 days of abstinence, and may be most pronounced when cannabis use is initiated during adolescence (Hanson et al., 2010; Medina et al., 2007; Pope, Gruber, Hudson, Huestis, & Yurgelun-Todd, 2001), although some evidence indicates other domains may not recover after adolescent cannabis use (Meier et al., 2012). In contrast, anecdotal (Wesnes & Warburton, 1983) and experimental data (Heishman et al., 2010; West & Hack, 1991) suggest that acute tobacco use results in improvements in concentration and memory. Indeed, studies have cited the possible benefits of nicotinic agents in attenuating memory-related impairments common to many neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders (Evans & Drobes, 2009; Levin, McClernon, & Rezvani, 2006). On the other hand, recent evidence suggests chronic tobacco use may be associated with deficits in attention and some aspects of memory (Chamberlain, Odlaug, Schreiber, & Grant, 2012; Durazzo, Meyerhoff, & Nixon, 2012).

Although not yet extensively studied, the few available findings on conjoint cannabis and tobacco use on memory provide preliminary evidence that the memory profile of a cannabis user varies according to the level of co-occurring tobacco engagement. Jacobsen and colleagues (2007) noted significant deficits in delayed verbal recall among abstinent adolescent cannabis users during nicotine withdrawal, but not during ad libitum smoking. Further, cannabis users who did not smoke a cigarette before the memory task evidenced increased activation in posterior cortical regions and disrupted functional integration of frontoparietal connectivity (Jacobsen et al., 2007), neural systems related to efficient verbal memory (Derrfuss, Brass, & von Cramon, 2004). Although still speculative, it is suspected that cannabis disrupts episodic memory and these deficits may be partially masked with co-occurring tobacco use. However, research on this topic is limited, precluding a clear understanding on the influence of tobacco on cannabis-induced memory decrements.

Taken together, it is well documented that cannabis and tobacco target memory-relevant brain structures and may exert opposite influences on episodic memory. The compensatory effect of tobacco use may be especially relevant among young adult cannabis users who are at increased risk of experiencing neurocognitive decrements due to heightened neuromaturational sensitivities during this period, as well as low cannabis exposure thresholds necessary to yield memory impairments (Cha, White, Kuhn, Wilson, & Swartzwelder, 2006; Schneider, Schomig, & Leweke, 2008). This study examines whether the episodic memory profile of young adult, regular cannabis users varies according to level of past year tobacco exposure. It is hypothesized that individuals will perform worse on memory measures with increasing amounts of past year cannabis consumption. However, we suspect that this negative association between cannabis use and memory functioning will differ according to their level of past year tobacco use. More specifically, we hypothesize that the relationship between cannabis use and memory will be stronger among those who use less tobacco. The goal of this study is ultimately to provide a more nuanced understanding of cannabis' association with memory functioning by taking into account co-morbid tobacco use.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 64 urban, young adult cannabis users (Female: n=23) with a mean age of 20.81 years (SD=1.82). Individuals were recruited for a laboratory-based study of cannabis use and neurocognition, which was comprised of toxicology tests, self-report questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and neurocognitive testing. For inclusion in the study, participants needed to report over 200 cannabis use occasions, use of cannabis more than four times per week during peak use, use of cannabis in the last 45 days, and identify cannabis as their drug of choice. The sample was free from multiple factors that might adversely impact neurocognition (e.g., lifetime use of other illegal substances on more than 10 occasions other than hallucinogens, current DSM-IV mood diagnoses, and CNS-compromising disorders including but not limited to epilepsy, tumors of the nervous system, multiple sclerosis, and stroke). More detailed information on study recruitment, and procedures can be found in other manuscripts using this sample (Gonzalez et al., 2012; Schuster, Crane, Mermelstein, & Gonzalez, 2012).

Measures

Participants were queried on demographics and potential premorbid and psychiatric confounds, including medical history, current/past mood disorders (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002), depression symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory–2ndEdition, Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory; Beck & Steer, 1990), use of psychotropic medications, premorbid full scale IQ (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading; Wechsler, 2001), ADHD symptoms (Wender-Utah Rating Scale; Ward, Wender, & Reimherr, 1993), and trait impulsivity (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11, BIS; Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995). Detailed interviews were conducted with each participant to ascertain approximations of cumulative amount of past year cannabis, alcohol and tobacco use. This approach employed modified timeline follow-back procedures, similar to methods employed in other studies (Cherner et al., 2010; Gonzalez et al., 2012; Rippeth et al., 2004; Schuster et al., 2012), and involved gathering retrospective estimates of amount of daily cannabis (reported in or converted to grams), alcohol (reported in or converted to standard drinks) and tobacco (reported in or converted to cigarettes) use over the year prior to the study visit. Amount of use per substance was summed to arrive at a cumulative estimate of amount of past year consumption. Current and lifetime substance use diagnoses were assessed with the SCID. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT-R; Benedict, Schretlen, Groninger, & Brandt, 1998) was used to capture episodic auditory/verbal memory (for more details on use of the HVLT-R in this sample, see (Schuster et al., 2012)). Dependent variables included z-scores on the number of words acquired in the first learning trial (Initial Acquisition), total words recalled across three learning trials (Total Learning), total words recalled after a 20-minute delay (Delayed Recall), and number of words correctly identified on a recognition trial minus the number of false alarm errors (Recognition Discriminability). Scores were generated using published normative data (Benedict et al., 1998).

General Statistical Approach

JMP Pro 11.0 (SAS, Cary, NC) was used to conduct analyses. We inspected data for non-normal distribution and outliers and performed log transformations (i.e., for amount of past year cannabis, tobacco and alcohol use) or nonparametric procedures when assumptions of normality were violated. To examine whether the relationship between amount of cannabis use and episodic memory varied according to amount of tobacco exposure, we conducted moderated multiple regressions with centered scores representing past year tobacco use, past year cannabis use, and their interaction term as predictors and indices of episodic memory as separate dependent variables. Omnibus models that included interaction terms treated cannabis and tobacco as continuous variables. Moderated regression analyses controlled for participant race as well as several covariates that were believed to be theoretically associated with memory performance, including years of education, level of self-reported impulsivity on the BIS, and amount of past year alcohol use. Significant interactions were followed-up with simple slope analyses of amount of past year cannabis use on memory performance with participants stratified based on average level of past year tobacco use: sporadic users (less than 100 cigarettes in the past year; n= 34) and consistent tobacco users (more than 100 cigarettes in the past year; n=30). T-tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and chi-squared analyses were then conducted to determine whether sporadic and consistent tobacco users differed on any potential sociodemographic confound. Results were statistically significant when p-values<.05.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Sample demographics and rate of endorsement of possible mental health and substance use confounds are represented in Table 1. As noted from this table, this sample had minimal mental health symptoms. With the exception of cannabis, tobacco, and alcohol, participants endorsed low levels of current and lifetime exposure to other drugs.

Table 1. Demographics and Mental Health Confounds.

| N =64 | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age | 20.81 (1.82) |

| % Female | 35.94% |

| Estimated FSIQ | 101.52 (11.14) |

| Years of Education | 13.52(1.71) |

| Ethnicity/Race | |

| Caucasian | 42.19% |

| Black | 37.50% |

| Hispanic | 10.94% |

| Asian | 6.25% |

| Other | 3.12% |

| Annual Income in Thousands of Dollars [Md, IQR] | 26.50 [8.18, 71.25] |

| Mother's Education | 14.53 (2.45) |

| Mental Health | |

| Past Major Depressive Disorder (SCID) | 19.05% |

| BDI-II Total Score [Md, IQR] | 5 [2, 8.75] |

| BAI Total Score [Md, IQR] | 4 [2, 8] |

| WURS, % of scores >46 | 4.69% |

| BIS-11 Total Score | 59.08 (9.91) |

| Substance Use | |

| Years of cannabis use | 5.02 (2.39) |

| Days since last cannabis use | 3.5 [2, 5] |

| % THC+ | 78.13% |

| Current (30 day) DSM-IV SUD | |

| Alcohol Abuse | 6.25% |

| Alcohol Dependence | 0% |

| Cannabis Abuse | 34.38% |

| Cannabis Dependence | 25.00% |

| Lifetime DSM-IV SUD | |

| Alcohol Abuse | 18.75% |

| Alcohol Dependence | 1.56% |

| Cannabis Abuse | 43.75% |

| Cannabis Dependence | 32.81% |

| Amount Used in Lifetime[Md, IQR] | |

| Alcoholic drinks | 381 [139.50, 1263] |

| Cigarettes | 1440 [24, 6930] |

| Cannabis (grams) | 487.92 [182.46, 1467] |

| Amount Used in Past Year [Md, IQR] | |

| Alcoholic drinks | 102 [26.75, 261] |

| Cigarettes | 72 [.25, 936] |

| Cannabis (grams) | 114 [48.50, 345] |

| Amount Used in Past 30 days [Md, IQR] | |

| Alcohol drinks | 9 [2, 20] |

| Cigarettes | 9 [0, 82.50] |

| Cannabis (grams) | 10.75 [3.25, 30] |

| Episodic Memory Performance | |

| HVLT-R Immediate Recall (z score) | Z= -.62 (1.02) |

| HVLT-R Total Learning (z score) | Z= -.74 (1.30) |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall (z score) | Z= -.79 (1.24) |

| HVLT-R Recognition Discrimination (z score) | Z=.03 (.87) |

Note: All values are means and standard deviations, unless otherwise noted; Md, Median; IQR, interquartile range; FSIQ, Full Scale IQ; BDI-2, Beck Depression Inventory-2nd Edition; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; WURS, Wender-Utah Rating Scale; BIS, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11th version; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SUD Substance Use Disorder diagnosis; THC+, positive rapid urine toxicology testing for cannabis; HVLT-R, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised

Cannabis and Tobacco Interactions on Episodic Memory

As detailed in Table 2, there was a significant interaction between cannabis and tobacco on Initial Acquisition, Total Learning and Delayed Recall, even after controlling for race, years of education, BIS and amount of past year alcohol use.

Table 2. Interactions between Amount of Past Year Cannabis and Tobacco Use on Episodic Memory.

| β | t | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Initial Acquisition (z score) | |||

| Years of Education | .27 | 1.86 | .07 |

| Race | |||

| White | -.01 | -.08 | .94 |

| Black | -.23 | -1.32 | .19 |

| Asian | .12 | .82 | .41 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | -.20 | -1.35 | .18 |

| More Than One Race | .06 | .46 | .65 |

| Impulsivity | -.14 | -.85 | .40 |

| Past Year Alcohol Use | .09 | .52 | .65 |

| Past Year Tobacco Use | .01 | .04 | .97 |

| Past Year Cannabis Use | -.03 | -.19 | .85 |

| Tobacco Use * Cannabis Use | .26 | 2.12 | .04 |

| DV: Total Learning (z score) | |||

| Years of Education | .25 | 1.72 | .09 |

| Race | |||

| White | -.11 | -.64 | .52 |

| Black | -.27 | -1.57 | .12 |

| Asian | .12 | .85 | .40 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | -.11 | -.77 | .44 |

| More Than One Race | -.07 | -.56 | .58 |

| Impulsivity | -.31 | -1.93 | .06 |

| Past Year Alcohol Use | .10 | .72 | .47 |

| Past Year Tobacco Use | .10 | .72 | .47 |

| Past Year Cannabis Use | 0 | 0 | .99 |

| Tobacco Use * Cannabis Use | .26 | 2.11 | .04 |

| DV: Delayed Recall (z score) | |||

| Years of Education | .11 | .73 | .47 |

| Race | |||

| White | -.17 | -1.01 | .31 |

| Black | -.48 | -2.71 | .01 |

| Asian | .02 | .11 | .91 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | .06 | .42 | .67 |

| More Than One Race | -.04 | -.32 | .75 |

| Impulsivity | -.48 | -2.92 | .01 |

| Past Year Alcohol Use | -.07 | -.51 | .61 |

| Past Year Tobacco Use | .23 | 1.69 | .10 |

| Past Year Cannabis Use | .08 | .53 | .60 |

| Tobacco Use * Cannabis Use | .28 | 2.21 | .03 |

| DV: Recognition Discriminability (z score) | |||

| Years of Education | -.09 | -.56 | .57 |

| Race | |||

| White | -.04 | -.25 | .80 |

| Black | .13 | .71 | .48 |

| Asian | .23 | 1.52 | .13 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | -.26 | -1.66 | .10 |

| More Than One Race | .13 | .92 | .36 |

| Impulsivity | -.20 | -1.18 | .24 |

| Past Year Alcohol Use | .21 | 1.45 | .15 |

| Past Year Tobacco Use | .12 | .83 | .41 |

| Past Year Cannabis Use | -.23 | -1.44 | .15 |

| Tobacco Use * Cannabis Use | .01 | .11 | .91 |

To follow-up significant interactions, simple slope analyses were conducted and revealed that more past year cannabis was associated with poorer Initial Acquisition (β=-.38, p=.03), Total Learning (β=-.37, p=.03) and Delayed Recall (β=-.41, p=.02) only among sporadic tobacco users (Figure 1). There was no relationship between amount of cannabis and episodic memory among consistent tobacco users (p-values>.55). Simple slope analyses were also conducted again after controlling for all covariates included in the omnibus models (i.e., race, years of education, BIS, amount of past year alcohol use), and importantly, the pattern of relationships remained the same. Among sporadic tobacco users, higher levels of past year cannabis use was associated with worse Delayed Recall (β=-.35, p=.04) and was marginally negatively associated with Initial Acquisition (p=.089) and Total Learning (p=.067), likely due to substantial reductions in power due to the added covariates.

Figure 1. Interactions between Amount of Cannabis and Tobacco Use on Episodic Memory Performance.

Sporadic and consistent past year tobacco users were compared on relevant demographic, mental health and substance use factors to determine whether any third variable could account for the observed effects. Importantly, they did not differ on several potential confounds including those related to demographics (i.e., age, p=.09; race, p=.65; gender, p=.35; years of education, p=.29; estimated IQ; p=.68), mental health (i.e., current symptoms of depression, p=.17; anxiety, p=.35; impulsivity, p=.09; and ADHD, p=.48), and substance use (i.e., amount of lifetime, p=.58, past year, p=.43, and past month p=.41 alcohol use; current and lifetime alcohol use disorders, p=.23 to 1.00; amount of lifetime, p=.56, past year, p=.79, and past month p=.23 cannabis use; time since last use of cannabis, p=.44; years of cannabis use, p=.96; current and lifetime cannabis use disorder diagnoses, p= .48 to .77).

As expected, consistent tobacco users compared to sporadic tobacco users reported more cumulative (Consistent: 5820 cigarettes [1968.25, 14346], Sporadic: 27 cigarettes [0, 514]; p<.0001), past year (Consistent: 1044 cigarettes [285, 2679.38], Sporadic: 1.5 cigarettes [0, 13.5] ; p<.0001) and past month (Consistent: 95 cigarettes [30, 187.50], Sporadic: 0 cigarettes [0, 2] ; p<.0001) tobacco use. Additionally, consistent tobacco users were more likely to have ever used tobacco regularly (Consistent: 86.67% ever regular smokers, Sporadic: 35%% ever regular smokers; p=.002) and had higher exhaled carbon monoxide than sporadic tobacco users at the outset of their study visit (Consistent: 3ppm, [2, 7.5]; Sporadic: 2ppm, [1, 3]; p=.005). Additionally of note, sporadic and consistent tobacco users did not differ on Initial Acquisition (p=.82), Total Learning (p=.75), Delayed Recall (p=.28), or Recognition Discriminability (p=.16) on the HVLT-R.

Discussion

Co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use is prevalent among young adults, but it is not clear how tobacco use alters the cognitive profile typically observed among cannabis users. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examines the interaction between cannabis and tobacco on episodic memory. We examined the relationships between amount of past year cannabis and tobacco use on four indices of episodic memory among young adults who identified cannabis as their drug of choice. Cannabis users in this sample performed approximately 0.75 standard deviations below normative standards on most indices of episodic memory. The emergence of interactions lends preliminary support to our hypothesis that memory impairments among cannabis users vary across levels of tobacco use. Specifically, more cannabis use was linked with poorer initial acquisition of words, total immediate recall of words across multiple learning trials, and total words spontaneously retrieved after a delay, but only among cannabis users who sporadically used tobacco within the last year. Amount of past year cannabis use was not associated with episodic memory among individuals who more consistently smoked cigarettes (i.e., more than 100 cigarettes in the last year).

These data provide preliminary evidence that interactive effects may be isolated to the unique contribution of tobacco use due to the fact that sporadic and consistent past year tobacco users were comparable across multiple demographic, substance use and mental health confounds. Additionally, interaction effects emerged after adjusting for demographic and theoretically relevant covariates. When simple slope analyses were conducted controlling for race, years of education, impulsivity and amount of past year alcohol use, the pattern of results was unchanged, yet some of the effects were reduced to marginal significance. In light of modest sample sizes and given that none of the covariates were statistically different between consistent and sporadic tobacco users, our inability to detect group differences in much more conservative analyses is likely attributable to insufficient power. Future studies that employ larger samples are warranted to determine the specificity of these effects and to examine the contribution of other factors not captured in this investigation on these observed relationships.

We suspect that our findings reflect cannabis-associated decrements in episodic memory, which may be attenuated with more tobacco use. Although the specific biochemical consequences of THC and nicotine interactions have only been studied minimally in animals (Valjent et al., 2002) and not at all in humans, preclinical investigations suggest that the opposing influences of cannabis and tobacco on memory may be attributable to alterations in synaptic plasticity that constitute core physiological components of learning and memory (Sullivan, 2000). More specifically, inhibition of presynaptic neurotransmitter release by THC is thought to disrupt long-term potentiation and long-term depression in the frontal lobe and hippocampus (Misner and Sullivan, 1999; Auclair et al., 2000), whereas stimulation of nAChRs via nicotine may induce long-term potentiation in similar regions (Matsyama & Matsymoto, 2003; Yamazaki et al., 2002). Therefore, it is possible that nicotine may mask or compensate for cannabis-induced memory deficits by temporarily improving long-term potentiation in regions central to memory functioning (although not directly tested in this study). This notion is supported by animal models showing that prolonged co-use of cannabis and tobacco results in changes in the sensitivity of hippocampal CB1 receptors and nAChRs over time (Mateos et al., 2011). Although some preliminary work in human investigations has similarly implicated the hippocampus in the interaction between cannabis and tobacco (Jacobsen et al., 2007), the involvement of specific neurobiological mechanisms for our findings is still speculative. It will be important for future investigations to compare brain functioning under conditions of single substance use as compared to concomitant cannabis and tobacco use as well as to better understand the stability of these alterations over time.

A strength of our study is that we investigated how cannabis and tobacco interact to affect multiple components of episodic memory (i.e., initial acquisition, total learning, delayed recall and recognition discriminability), rather than relying on a single index. Episodic memory is multi-dimensional and difficulties may occur at various stages of the encoding and retrieval process. Our results showed that initial acquisition, total learning and delayed recall were most related to amount of cannabis use when levels of past year tobacco exposure were lower. Findings are consistent with other investigations that show cannabis to have an adverse impact on distinct phases of memory processing (Miller, McFarland, Cornett, Brightwell, & Wikler, 1977; Niyuhire, Varvel, Martin, & Lichtman, 2007). For instance, preclinical evidence shows that smoked cannabis and injected Δ9-THC are disruptive to both learning and retrieval in mice, independent of initial acquisition (Niyuhire et al., 2007). Although this investigation was able to examine multiple components of memory, this was conducted only through a single measure (HVLT-R) and future studies would benefit from larger samples and more comprehensive batteries of memory assessments including verbal, nonverbal, working, prospective, and procedural memory using a variety of psychometrically validated tools to help clarify the memory profile of co-morbid cannabis and tobacco users, Additionally, further research is warranted to determine whether these results replicate in instances of acute and simultaneous cannabis and tobacco use (i.e., “blunt” smoking, “mulling” or “chasing”). In ongoing investigations, we are examining how simultaneous cannabis and tobacco administration impacts working memory using real-time data capture methodology. Data from the current investigation, alongside those being collected in our other study, will help to better understand how co-use of cannabis and tobacco impacts memory during acute intoxication and abstinence, and the stability of these associations over time.

Although we suspect that results can be explained by a buffering effect of tobacco on cannabis-associated memory deficits, our study design precludes us from definitively affirming our hypothesis. Our study was limited to investigating conditional effects, and did not examine the mechanisms subserving these interactions. There are other possible explanations to our findings that cannot be ignored. For example, we were not able to control for the potential impact of nicotine withdrawal on results; however, we think our assessment procedures minimized any such effects. We did not require our participants to be abstinent from tobacco and they were allowed to take smoking breaks at anytime during the protocol. Yet, no participants took advantage of this option suggesting that they likely were not experiencing substantial symptoms of withdrawal as well as reducing any potential uneven benefit of acute tobacco exposure on cognitive functioning. Additionally, all protocol instruments (including the HVLT-R) were counterbalanced, making it highly unlikely that there was a systematic effect of acute nicotine withdrawal on episodic memory. Regardless, future studies that specifically measure levels of nicotine withdrawal are needed (e.g., controlling for time since last use, including measures of nicotine craving and nicotinic biomarkers such as cotinine). It will also be critical that the relative contributions of enhanced cognitive functioning from acute tobacco exposure versus the reversal of nicotine withdrawal be determined. This may be accomplished through assessing memory functioning as well as changes in neurochemistry and neurocircuitry before and after nicotine exposure among a tobacco-naïve population, although this may present obvious ethical concerns. Alternatively, studies may minimize the complicating effects of nicotine withdrawal by examining changes in memory and its neural correlates during simultaneous cannabis and tobacco use (e.g., blunt smoking, “chasing”) among regular users. Regardless of the chosen methodology, understanding the way in which tobacco alters the cognitive profile from cannabis use (i.e., through reversal of withdrawal emergent deficits or compensation for cannabis-induced decrements) will be critical for developing effective interventions for youth who may be addicted to both substances.

Results from the current investigation should be examined in the context of several limitations. First, this study did not assess for motivational factors surrounding co-use, making it difficult to determine whether cannabis users purposefully used tobacco to “self-medicate.” Second, our sample was comprised of a relatively healthy group of cannabis users, which may limit generalizability to cannabis users with involvement with multiple substance classes. However, this offers the benefit of better isolating potential effects of cannabis and nicotine in the sample in combination with our controlling for alcohol use. Additionally, among those classified as more consistent tobacco users, there remained variability in the amount of their past year tobacco exposure. Future investigations with large sample sizes will be able to examine the specificity of the effects observed in this study based on a more nuanced classification of tobacco use. Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study limits our ability to draw causal inferences and establish temporal precedence between study variables. Future investigations will benefit from employing a longitudinal design to address the relationships between changing patterns of cannabis and tobacco co-use and episodic memory.

In sum, these data provide important insight into a potential mechanism (i.e., attenuation of cognitive decrements) that might reinforce use of both substances and hamper cessation attempts among cannabis users who also smoke cigarettes. However, it is critical to underscore that these findings do not encourage tobacco use among cannabis users. Especially given that the effect sizes found in the current study were small to moderate, it is very highly unlikely that any possible cognitive-enhancing effects would outweigh the numerous documented health risks from tobacco (e.g., cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, reproductive effects, and cancer). Instead, these results are valuable due to their relevance in informing the development of more tailored and targeted intervention efforts for the growing number of individuals who use both cannabis and tobacco.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (K23 DA023560, R01 DA031176, and R01 DA033156, PI: RG); the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH) (T32MH067631, to NAC); and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (P01CA098262, PI: RM). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA, NCI or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1998;12(1):43–55. doi: 10.1076/clin.12.1.43.1726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance--United States. 2013;2012 [Google Scholar]

- Cha YM, White AM, Kuhn CM, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Differential effects of delta9-THC on learning in adolescent and adult rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;83(3):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Odlaug BL, Schreiber LR, Grant JE. Association between tobacco smoking and cognitive functioning in young adults. Am J Addict. 2012;21 Suppl 1:S14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherner M, Suarez P, Casey C, Deiss R, Letendre S, Marcotte T, et al. Heaton RK. Methamphetamine use parameters do not predict neuropsychological impairment in currently abstinent dependent adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrfuss J, Brass M, von Cramon DY. Cognitive control in the posterior frontolateral cortex: evidence from common activations in task coordination, interference control, and working memory. Neuroimage. 2004;23(2):604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ, Nixon SJ. A comprehensive assessment of neurocognition in middle-aged chronic cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(1-2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, Drobes DJ. Nicotine self-medication of cognitive-attentional processing. Addict Biol. 2009;14(1):32–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition. New York: New York Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R, Schuster RM, Mermelstein RJ, Vassileva J, Martin EM, Diviak KR. Performance of young adult cannabis users on neurocognitive measures of impulsive behavior and their relationship to symptoms of cannabis use disorders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34(9):962–976. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2012.703642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S, Cascio MG, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Fezza F, Di Marzo V, Ramos JA. Changes in endocannabinoid contents in the brain of rats chronically exposed to nicotine, ethanol or cocaine. Brain Res. 2002;954(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KL, Winward JL, Schweinsburg AD, Medina KL, Brown SA, Tapert SF. Longitudinal study of cognition among adolescent marijuana users over three weeks of abstinence. Addict Behav. 2010;35(11):970–976. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Kleykamp BA, Singleton EG. Meta-analysis of the acute effects of nicotine and smoking on human performance. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210(4):453–469. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1848-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Pugh KR, Constable RT, Westerveld M, Mencl WE. Functional correlates of verbal memory deficits emerging during nicotine withdrawal in abstinent adolescent cannabis users. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, McClernon FJ, Rezvani AH. Nicotinic effects on cognitive function: behavioral characterization, pharmacological specification, and anatomic localization. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184(3-4):523–539. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K. Distribution of cannabinoid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005;(168):299–325. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EM, Granstrem O, Moreno E, Llorente R, Adriani W, Laviola G, Viveros MP. Subchronic nicotine exposure in adolescence induces long-term effects on hippocampal and striatal cannabinoid-CB1 and mu-opioid receptors in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos B, Borcel E, Loriga R, Luesu W, Bini V, Llorente R, et al. Viveros MP. Adolescent exposure to nicotine and/or the cannabinoid agonist CP 55,940 induces gender-dependent long-lasting memory impairments and changes in brain nicotinic and CB(1) cannabinoid receptors. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(12):1676–1690. doi: 10.1177/0269881110370503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina KL, Hanson KL, Schweinsburg AD, Cohen-Zion M, Nagel BJ, Tapert SF. Neuropsychological functioning in adolescent marijuana users: subtle deficits detectable after a month of abstinence. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(5):807–820. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707071032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RS, et al. Moffitt TE. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(40):E2657–2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LL, McFarland DJ, Cornett TL, Brightwell DR, Wikler A. Marijuana: effects on free recall and subjective organization of pictures and words. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1977;55(3):257–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00497857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyuhire F, Varvel SA, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Exposure to marijuana smoke impairs memory retrieval in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322(3):1067–1075. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: a systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(8):1404–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Caldarone BJ, King SL, Zachariou V. Nicotinic receptors in the brain. Links between molecular biology and behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22(5):451–465. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Gruber AJ, Hudson JI, Huestis MA, Yurgelun-Todd D. Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(10):909–915. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Delucchi KL, Liu H, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Young adults who smoke cigarettes and marijuana: Analysis of thoughts and behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Carey CL, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Gonzalez R, et al. Grant I. Methamphetamine dependence increases risk of neuropsychological impairment in HIV infected persons. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;10:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Schomig E, Leweke FM. Acute and chronic cannabinoid treatment differentially affects recognition memory and social behavior in pubertal and adult rats. Addict Biol. 2008;13(3-4):345–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster RM, Crane NA, Mermelstein R, Gonzalez R. The influence of inhibitory control and episodic memory on the risky sexual behavior of young adult cannabis users. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18(5):827–833. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712000586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD (2012)

- Viveros MP, Marco EM, File SE. Nicotine and cannabinoids: parallels, contrasts and interactions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(8):1161–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):885–890. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wesnes K, Warburton DM. Effects of smoking on rapid information processing performance. Neuropsychobiology. 1983;9(4):223–229. doi: 10.1159/000117969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R, Hack S. Effect of cigarettes on memory search and subjective ratings. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;38(2):281–286. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90279-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]