Overview and Grand Health Challenges

Bio-MEMS (Biological or Biomedical Micro Electro Mechanical Systems) are poised to have a significant impact on clinical and biomedical applications. These devices, also termed ‘Lab on Chip’, or ‘Point of Care Sensors’ represent a significant opportunity in various patient-centric settings including at home, the doctor’s office, in ambulances on the way to the hospital, in emergency rooms, at the hospital bedside, in rural and global health settings, and in clinical or commercial diagnostic laboratories. The potential impact of these technologies on the early diagnosis and management of disease can be very high for sensing and reporting on parameters ranging from physiological to biomolecular. As healthcare delivery and management becomes increasingly personalized and individualized, and as genomic, proteomic, and metabolic technologies unravel the human genetic and epi-genetic dispositions to disease, detection of multiple markers (at any of the ‘Omics’ scale) at an individualized level to assess the state of health and disease will become even more important.

Various diseases afflicting the human condition worldwide and in the US can be generally categorized into communicable or non-communicable diseases. The eradication and management of these diseases represent one of the biggest challenges facing modern day society both in terms of loss of human lives and monetary burdens on society. The key communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, and other diseases caused by infectious agents continue to be a major cause of death and suffering worldwide. The key non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases have emerged relatively unnoticed in the developing world and are now becoming a global epidemic. In 2008, 36 million people died from non-communicable diseases world-wide, representing 63% of the 57 million global deaths that year (Figure 1a). By 2030, non-communicable diseases are projected to claim the lives of 52 million people, nearly five times as many deaths as communicable diseases worldwide, including in low- and middle-income countries [1].

Figure 1.

(a) Total deaths world-wide by broad cause group, World Bank income group and sex, 2008 (adapted from WHO, The Global Status Report on Non-communicable Diseases 2010[1], (b) Cause of death for all ages in 2007 in the USA. Note CLRD is Chronic Lower Respiratory Diseases [3].

Point-of-care, clinical BioMEMS can make a significant impact on these grand challenges. Cancer and cardiovascular diseases are the two leading causes of death in the US, as shown in Figure 1b. In 2010, about 1.5 million Americans were diagnosed with cancer and about 570,000 were expected to die of cancer[2]. The National Institutes of Health estimates overall costs of cancer in 2010 at $263.8 billion. In spite of a considerable effort, there has been limited success in reducing per capita deaths from cancer since 1950. This calls for a paradigm shift in the understanding, detection and intervention of the evolution of cancer from a single cell to tumor scale. Point-of-care clinical bioMEMS can be used for collection of circulating tumor cells, detection of protein or DNA cancer biomarkers from serum, collection of exosomes and detection of miRNA for cancer detection and epigenetic analysis.

Similarly, infectious diseases cause loss of life in the USA at 4% of total deaths, which appears to be much smaller than cancer and heart disease, but take a huge toll on our medical and financial system due to the need for testing in medical labs and hospitals. Worldwide, between 14-17M people die of infectious diseases and mostly in developing countries. The global health crisis has impacted hundreds of millions of people with HIV/AIDs, Malaria, TB, etc. With over 33 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the world, obtaining accurate helper T cell and viral load counts at regular intervals is crucial in monitoring the health of an HIV-positive patient’s immune system. Rapid and point-of-use detection of these infectious diseases could dramatically change how these diseases are managed and treated.

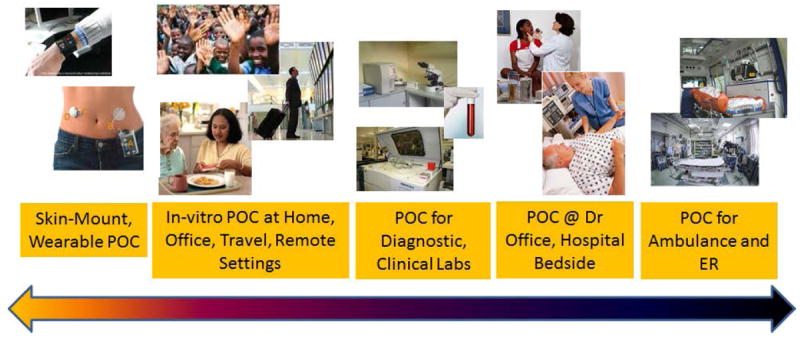

From the user’s perspective, these BioMEMS devices for clinical, point-of-care, and biomedical applications can potentially be used in a variety of settings as shown in Figure 2. The settings can range from individualized skin-mount devices measuring vitals and physiological parameters from skin or beneath the skin, to in-vitro analysis of body fluids for markers or diseases or target cells, to one-time-use devices at diagnostic laboratories, doctor’s office, or bed-side in the hospital. Rapid diagnostics at these above-mentioned settings in addition to transit to the hospital in ambulance or in emergency room settings are also critically needed.

Figure 2.

Application and settings where clinical Point-of-Care (POC) can be used – ranging from personalized to hospital and ER settings

Attributes of Biochip Sensors

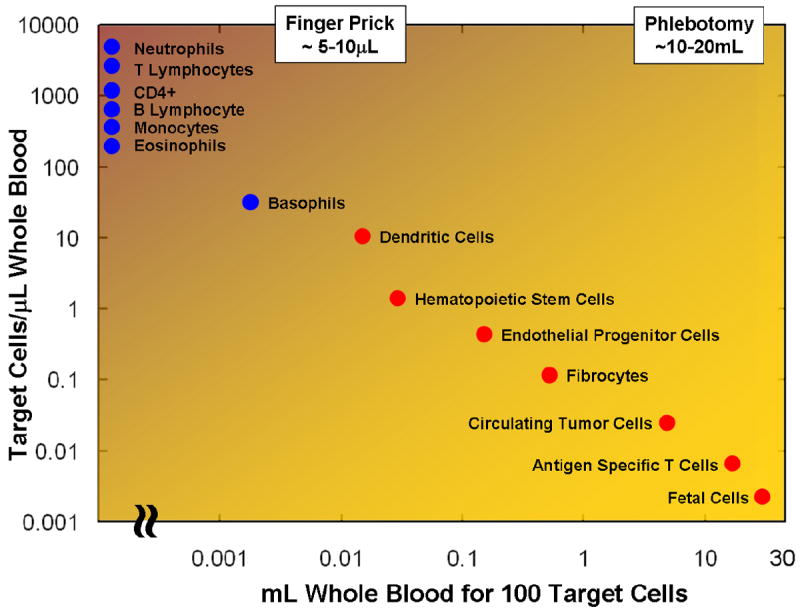

These BioMEMS and Biochips are built in silicon, plastics, or polymer using micro and nano-fabrication technologies. The devices include microfluidic elements such as channels and wells for fluid and sample transport, and could employ a range of processing, separation, and sensing modalities (optical, electrical, etc.) [4]. These devices can also have integrated sample preparation modules, and biological recognition elements such as antibodies or DNA molecules for selective capture on the same chip sensor. Clinical fluids of interest can provide a rich source of diagnostic and prognostic markers for various diseases. The possible targets from clinical fluids of interest include cells, bacteria, viruses, exosomes, protein or nucleic acid based biomarkers, or small molecules – where many or all of these targets could find their way in body fluids such as blood, urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, etc. Blood is especially a unique tissue with target analytes which can be used for either early detection or determining the progression of disease [5]. However, extracting and separating the target entities of interest from blood can be especially challenging. As depicted in Figure 4, separating target subpopulations of cells from whole blood requires the handling of volumes of blood that can span more than three orders of magnitude.

Figure 4.

Mining Blood for Cellular Information. Human blood contains a large variety of cells that are important for clinical diagnostic or monitoring of treatment. Separating target subpopulations from whole blood requires the handling of volumes of blood that can span more than three orders of magnitude.

The diagnostics and prognostics for diseases could represent the largest and most fruitful area in BioMEMS. Figure 3 depicts a schematic overview of such a device highlighting the various steps for detection and analysis of biological targets for clinical or biomedical applications. In general, the use of micro- and nano-scale technologies is well justified due to the following reasons; (i) reduced time-to-result due to small volumes resulting in higher effective concentrations, (ii) reducing the sensor element to the scale of the target species and hence providing a higher sensitivity, (iii) reduced reagent volumes and associated costs, (iv) providing for one-time-use disposable sensors and cartridges, and (v) possibility of portability and miniaturization of the entire system. Various sensing modalities are used in these devices including optical, electrical, or mechanical. Optical detection techniques are perhaps the most common due to their wide use in biology and life sciences. Optical detection techniques can be based on fluorescence or chemiluminescence. Miniaturization of electrophoresis devices, biomolecular sensors, and detectors has been of wide interest and as the quantity of reagents, sample, and labels are reduced, the demands on improving signal to noise ratio and sensitivity are increased. Mechanical detection for biochemical entities and reactions has more recently been used through the use of micro- and nano-scale cantilever sensors on a chip. These devices can be used in two modes, namely stress sensing and mass sensing. In stress sensing mode, the biochemical reaction is performed selectively on one side of the cantilever. A change in surface free energy results in a change in surface stress, which results in measurable bending of the cantilever. Thus, label-free detection of biomolecular binding can be performed. The bending of the cantilever can then be measured using optical means or electrical means. In the mass sensing mode, the cantilever is excited mechanically so that it vibrates at its resonant frequency. The resonant frequency is measured using electrical or optical means, and compared to the resonant frequency of the cantilever once a biological entity is captured. The mass change can be detected by detection of shift in resonant frequency. One of the main advantages of the cantilever sensors is the ability to detect interacting compounds without the need of introducing an optically detectable label on the binding entities. In the recent years, very exciting and significant advances in biochemical detection have been made using cantilever sensors and direct, label-free detection of a whole host of entities and mechanisms have been reported from DNA, protein, viruses, cells and cell growth [6-9].

Figure 3.

Sub-modules and functions that need to be performed inside a BioMEMS point-of-care Lab-on-chip device. The sample is processed and target analytes, molecules, or cells are captured via recognition elements. The target molecules or the source of the target, e.g. cells, are amplified. Finally the target is detected and identified using different possible approaches that could require a label or might be label-free.

In addition to the mechanical approaches listed above, electrical or electrochemical detection techniques have also been used in biochips and BioMEMS sensors. These techniques can be amenable to further portability and miniaturization, and hand held devices containing these sensors can be easily produced. Electrical detection includes the following basic types, namely; amperometric biosensors, which involves the electric current associated with the electrons involved in redox processes; conductometric, which measure conductance changes associated with changes in the overall ionic medium between the two electrodes; potentiometric biosensors, which measure a change in potential at electrodes due to ions or chemical reactions at an electrode (such as an ion Sensitive FET); and Giant Magneto Resistive (GMR) sensors, where a change in electrical conductivity is measured when biomolecule-laden magnetic beads are brought close thin GMR films. The most widely used example of amperometric sensing is that of detection of glucose, based on glucose oxidase, which generates hydrogen peroxide and gluconic acid in the presence of oxygen, glucose, and water. Then, hydrogen peroxide is reduced at 600 mV at Ag/AgCl anode reference electrode. Conductometric sensors measure the changes in the electrical impedance between two electrodes, where the changes can be at an interface or in the bulk region and can be used to indicate biomolecular reaction between DNA, proteins, and antigen/antibody reaction, or excretion of cellular metabolic products indicating cell growth [10]. And finally, potentiometric sensors utilize the measurement of a potential at an electrode in reference to another electrode. The most common form of potentiometric sensors are the ion-sensitive field effect transistors(ISFETs) or chemical field effect transistors (Chem-FETs). These devices are available commercially aspH sensors and many examples have been reported in literature. The potentiometric sensors have been downscaled to nano-meter dimension through the use of silicon nano-fabrication to take advantage of enhance sensitivity due to higher surface area to volume ratio [11]. Giant-magneto-resistive sensors require a magnetic particle as a label which is functionalized with capture molecules. The particle acts as a label in a sandwich ELISA format performed on thin micro-fabricated GMR films. These sensors, while requiring a magnetic label, can provide for a high sensitivity multiplexed detection of cancer markers, with high signal-to-noise ratio and wide dynamic range in clinical samples [12].

Exemplar 1: CBC on a Chip

A complete blood count (CBC) is a diagnostic screening tool that provides clinicians a broad assessment of a patient’s health status through a comprehensive analysis of his or her circulating blood cells. This fundamental test is normally ordered upon patient admission to obtain an initial snapshot of a patient’s health status, allowing clinicians to act rapidly in determining appropriate treatment for disorders such as infection, anemia, cancer, nutrient deficiency, and other diseases. Current CBC tests require multiple analysis tools and trained technicians, which not only makes the tests prohibitively expensive for many patients, but requires patients to travel to over-crowded centralized clinical facilities that may provide results in several days or even weeks. A ‘killer-application’ for point-of-care clinical BioMEMS could be a CBC on a chip, which could revolutionize the healthcare infrastructure by not only decreasing personal healthcare costs, but by providing a rapid and comprehensive assessment during a physician’s visit or even at the convenience in one’s own home, regardless of geographic and economic constraints.

As a basis of such a device, an HIV/AIDS diagnostics chip that selectively enumerates leukocytes and CD4+ T lymphocytes using affinity chromatography coupled with electrical impedance sensing has been recently reported [13]. The design employs the Coulter principle to electrically count the total number of purified leukocytes entering the chip before depleting CD4+ T lymphocytes in an antibody-coated capture chamber [14]. The CD4+ T cell count is then simply obtained by subtracting the entrance count from number of uncaptured leukocytes exiting the chip. This method has proven to correlate closely with an optical counting method with low inherent error, showing it to be a feasible technology for portable and rapid blood diagnostics.

An electrical chip-based CBC can be realized by using the differential counter module as a building block to enumerate and analyze the various blood cells (Figure 5). A whole blood sample is injected into the micro-fabricated chip and is equally split into two branches. Branch A selectively removes erythrocytes through a chemical reaction to lyse their membranes, leaving leukocytes intact [15]. The purified population of leukocytes can be split evenly among several differential counting modules with capture chambers coated with antibody concoctions specific to the five main leukocyte subtypes (e.g., CD19 antibody is specific to monocytes). The total leukocyte count is obtained at the entrance of each differential counter module. Additional capture chambers with other antibody mixtures can create a more comprehensive test, such as CD4+ T cells for HIV/AIDS diagnostics. Branch B analyzes the blood sample for platelet and erythrocyte concentrations by diluting the sample enough to ensure only one cell crosses the electrical sensing region at one instance [16]. In addition, the impedance pulse analysis enables the measurement of erythrocyte volume to obtain the hematocrit level (anemia) in addition to the average erythrocyte volume (iron, B12, folate deficiencies, and thalassemia) and erythrocyte distribution width (erythrocyte maturity).

Figure 5.

(a) Mapping of CBC on a chip. Inset: A differential counter design with (1) and entrance counter, (2) capture chamber, and (3) exit counter. Scale bar is 1 cm. Adapted from [18], (b) An n improved differential module, which has a (1) red blood cell lysis region, (2) lysis quenching region, (3) entrance counter, (4) capture chamber, and (5) exit counter.

Exemplar 2: Measuring Neutrophil Motility on a Chip

Neutrophils are the first line of defense against infections. They represent the most numerous sub-population of white blood cells in the blood and have the ability to migrate within minutes from the blood to the site of infection or injury in the tissues. They accomplish this demanding task by following chemical concentration gradients of attracting molecules released from the invading bacteria or the cells under stress. The motility function of the neutrophils is of great medical interest because failure of neutrophils to promptly arrive at sites of infection or inflammation can result in uncontrollable infections, while overzealous neutrophil infiltration can unnecessarily damage normal tissues and impair organ function e.g. in severe forms of asthma and arthritis, acute hepatitis, or ischemia-reperfusion injury. However, measuring the motility of neutrophils is not an easy task. In a research environment, most common protocols use Boyden chambers [17], however these device rely on gradients that can change in poorly controlled ways and they only provide limited information and indirect measures of motility e.g. the number of cells that pass through a membrane with pores.

The early application of microfluidic technologies to neutrophil motility studies helped solve the problem of gradient stability and facilitated the dynamic observation of neutrophil migration with single cell resolution [18]. Microfluidic devices quickly become research tools for important problems in the biology of neutrophil migration [19], from the migration against gradients [20], responses to changing gradients [21], or the integration of average and slope of chemical gradients [22]. However, moving forward from these pioneering devices to robust systems to measure neutrophil motility in clinical settings requires designs that can integrate an array of distinct functions to be integrated on the same chip. Devices should be able to separate the neutrophils from whole blood quickly and without activation, generate precise chemical gradients, and measure neutrophil motility parameters automatically, with minimal operation from the human operator. Recent advances in the field of microfluidic devices for neutrophil chemotaxis are encouraging that these goals may be achieved in the near future.

First, separating the neutrophils on the chip, can by-pass the complex procedures for isolating neutrophils from whole blood, speeding-up the assay and eliminating the need for bulky centrifugation equipment. One recent example is a microfluidic chip that can both isolate neutrophils and monitor their migration in stable chemical gradients [23]. Only a small drop of blood from the finger is required for the assay, orders of magnitude less than the standard assays. Neutrophils are captured inside the chip, in a chamber coated with cell adhesion molecules that interact weakly with the target cells. The same weak interactions allow the cells to move at the later step, when a concentration gradient of a chemo-attractant is applied. With the use of a microscope, images of the moving cells are captured and motility. Although effective, the arrangement of valves, inlets and outlets on the chip required to accomplish the sequence of steps for the assay could become problematic for automation. Second, the precision of measuring the neutrophil motility in microfluidic devices can reach beyond the capabilities of any other method available today. Such advance was possible through the use of linear channels with cross section smaller than the size of neutrophils (Figure 6), which could be regarded as the equivalent of speed tracks in the “macro world” [24]. Using this device, for the first time a normal range of neutrophil directional migration speed values was defined for healthy volunteers, independent of sex or age of the donor, and reproducible from the same volunteer at time points separated by weeks. The device also enabled the first precise measurement of the neutrophils motility alteration in hospitalized patients after burn injury. Although the device uses no external syringe pumps and has only one inlet and one outlet, it still requires the preliminary separation of neutrophils from the sample blood using standard techniques. Finally, high throughput devices capable of performing more than fifty neutrophil migration assays simultaneously have been reported through the use of microfluidic technologies [25]. The new platform can operate at single cell resolution to perform high content analysis of motile neutrophils in a large number of independent chemo-attractant conditions and screen for the effect of various drugs. However, neutrophils have to be purified separately before the assay, and the precision of measurements is limited by the physiological noisiness of speed and directionality during neutrophil migration on flat surfaces.

Figure 6.

Precise measure of neutrophil motility in a microfluidic chip. Neutrophils that are injected in the microfluidic device in the main channel, migrate laterally to enter an array of small channels filled with chemoattractant towards which they move at uniform speed.

Although some elementary functions have already been demonstrated, the integration of efficient separation, precise analysis and high throughput format functions in the same device is not a trivial task, and creative new protocols and technological developments are required to overcome current obstacles. When accomplished, this integration will bring provide new tools for the exploration of interesting biological questions and novel applications to clinical conditions. Evaluating the risk of infections in patients at risk, modulating immunosuppressive regiments after transplant, or monitoring the resolution of acute and chronic inflammation could be valuable insights enabled by devices for measuring neutrophil motility function in the doctor’s office.

Exemplar 3 : Bacterial Detection on a Chip

Capture and detection of bacteria and viruses from body fluids at point-of-care also represents a grand challenge. Figure 3 earlier depicted the concept schematic of a lab on chip that conforms well to the detection of infectious agents. Such as integrated device would be capable of separating and extracting bacteria from blood, perform sorting and concentration of these microorganisms if needed, perform antibody-based capture of target organisms, possibly perform bacterial culture inside the chip to determine presence of live or viable cells and also to increase the number of cells needed for analysis, then lyse those cells and perform a nucleic acid based identification of those cells.

The separation of the bacteria (1μm or so in size) or viruses (50-250nm in size) from the body fluids perhaps poses the greatest challenge as discussed earlier. Cells occur at much higher number and hence increase the background noise in any detection assays, especially from blood. The problem of viral separation is intensified due to the presence of similarly-sized exosomes which are present at much higher concentrations than target viruses. Red blood cells and hemoglobin also known to reduce the sensitivity of PCR assays and hence separation of the target bacteria (1um or so in size) and viruses (50-200nm in size) from other blood cells is critically important before the identification of these entities is performed.

For the case of identification, nucleic acid-based methods are still considered the gold-standard due to their high specificity and selectivity as compared to antibody-based assays. However, the high cost of reagents and instrumentation for optical detection of the amplified PCR (polymerase chain reaction) product, and the time it takes to perform the amplification has still limited the realization of these methods as truly a point-of-care test with total assay time of sample-to-result in, for example, less than 10 minutes. The grand challenge of taking a throat swab or sputum, or a sample (or drop) of blood or urine and obtaining an identification of bacteria or viruses at low concentrations for early detection still remains unfulfilled. The target bacterial counts can be just a few cfu (colony forming units) per ml of sample fluid at the onset of infections. In case of elevated infection levels, the numbers can be in tens of thousands to million bacteria per ml, in which case, the detection can be performed by current techniques. It should also be noted that many bacteria, for example, might survive or replicate within phagocytes. The best commercial assays for PCR claim 20 minutes of assay time from a 10-20μl sample as long as few copies of the target DNA are present in that volume. This means that for detection at low concentrations (onset or early detection), either the bacteria needs to be grown or amplified by traditional petri-dish cultures or separate or concentrated from a larger volume sample into smaller volumes, before they can be detected using bio-molecular assays. It should be noted that for detection of bacteria from drinking water, environmental samples, or pharmaceutical fluids, the target concentrations are even lower at 1cfu/100ml to 1cfu/250ml. for these applications, the advantages offered by microfluidics and lab-on-chip can only be useful if the target bacteria can be concentration from these large volumes down to 0.1-1ml of fluids before these are introduced into these small devices.

Integrated biochip devices have been demonstrated that can capture, trap and detect specific bacteria based on dielectrophoresis and antibody- mediated capture [26]. In addition, to reduce the time for detection of bacteria culture and perform the detection electrically, microfluidic chips in which a small number of bacterial cells could be concentrated from a dilute sample into nanoliter volumes, and then cultured have also been demonstrated. Figure 7 shows silicon biochip platforms used for these studies. Taking advantage of the small volume of the biochip, 104 to 105 fold concentrations of bacterial cells from a dilute sample can be achieved. Similar platforms can be used to perform Polymerase chain reaction amplification and detection of as few as 10-50 cells of Listeria monocytogenes has been performed using optical fluorescence detection [27].

Figure 7.

(a) Optical micrograph of a microfluidic biochip for bacterial culture and identification [14,26], (b) SEM images of the channels and wells inside the chip, and (c) concept schematic of a cartridge housing the chip along with reagents needed to perform biomolecular assays.

Exemplar 4: CTC-Chip and Circulating Tumor Cells for Cancer Diagnostics

Blood-borne metastasis is initiated by cancer cells that are transported through the circulation from the primary tumor to vital distant organs, and it is directly responsible for most cancer-related deaths [27]. However, CTCs are extraordinarily rare (estimated at one CTC per billion normal blood cells in the circulation of patients with advanced cancer) and they have proven very difficult to isolate in sufficient numbers to be clinically useful. The clinical use of CTCs is very broad and includes monitoring of individual patients with metastatic disease, noninvasive analysis of biomarkers and acquired resistance to specific treatment regimens in targeted therapies, and ultimately early detection of cancer. Despite the fact that the potential of CTCs in clinical management of cancer patients is significant, the bottleneck has been the development of highly sensitive, high throughput, and reliable technological platforms for isolation of CTCs from the peripheral blood of patients.

The most widely used CTC isolation techniques rely on antibody-based capture of CTCs, which express epithelial cell surface markers that are absent from normal leukocytes [28]. The Toner group has developed several microfluidic approaches called “CTC-Chip” for single-step isolation of CTCs from unprocessed blood specimens [29-32]. The first generation CTC-chip is composed of etched 78,000 microposts in silicon that are coated with an antibody specific to epithelial cells (Figure 8). Whole blood flows through the chip, the flow is precisely controlled to enhance interaction of cells with antibody-coated microposts to maximize binding of tumor cells to the surface of the microposts. Isolated CTCs are then analyzed either by direct imaging or by molecular approaches. flow kinetics has been optimized for minimal shear stress on cells while enhancing contacts with the antibody-coated microposts. The CTC-chip enables a high yield of capture (median, 50 CTCs per milliliter) and purity (ranging from 0.1 to 50%), most likely caused by the gentle one-step microfluidic processing, which may be critical when purifying rare delicate cell populations [29]. More recently, we have developed the second generation microfluidic technology using an enhanced platform called the herringbone (HB)-chip [32]. The HB-Chip makes use of a microvortex mixing device to capture CTCs from whole blood. The simple design of the HB-chip is conducive to high throughput manufacturing out of transparent materials, which greatly enhance high-resolution imaging, including the use of transmitted light microscopy. The ability to further simplify the device design and reduce the manufacturing cost while increasing reliability will ultimately enable validation of CTC-Chip in multi-center clinical trials for identification and validation of clinical utility.

Figure 8.

CTCs have a broad range of applications in the management of cancer patients. The two microfluidic technologies developed in the Toner group are called CTC-Chip and are based on chemical capture of CTCs from whole blood. The original work was based on increasing the interaction of CTCs with microposts that are chemically modified with an antibody to bind to CTCs and not to leukocytes or blood cells. The second generation technology replaced the microposts with herringbone pattern only on the top surface to achieve gently mixing of blood as it flows through the chip in order to bring CTCs in contact with the antibody coated surfaces of the CTC-Chip. The key structures in both cases vary between 20 to 50 microns. The details of the chip geometry are given elsewhere [29-32].

Summary

The future of Clinical and Point-of-Care BioMEMS is very bright. With an increasing emphasis on personalization of medicine, and the rising costs of health-care, early detection and diagnostics at the point-of-care will be even more important. Early detection implies early intervention - resulting in saving of lives and reducing overall spending. The potential impact of these technologies on the early diagnosis and management of both communicable and non-communicable diseases is very high. Many grand challenges applications are possible e.g. routine tests such as complete blood cell count on a chip that an individual can perform at home; detection of cardiac markers from blood after a perceived heart attack; detection of cancer markers such as exosomes, circulating tumor cells from blood, or protein biomarkers in serum; detection of infectious agents such as virus and bacteria for public health; etc. These applications are expected to result in new diagnostic assays for home, doctor’s office, clinical laboratories, and various point of care settings.

Contributor Information

M. Toner, Email: mtoner@hms.harvard.edu.

R. Bashir, Email: rbashir@illinois.edu.

References

- 1.WHO. The Global Status Report on Non-communicable Diseases. 2010 http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/66/83&Lang=E.

- 2.Cancer Facts and Figures 2010. American Cancer Society; http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/acspc-024113.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC/NCHS. Health, United States, 2010, Figure 24. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10_InBrief.pdf.

- 4.Bashir R. BioMEMS: State of the Art in Detection and Future Prospects. Advanced Drug Delivery Review. 2004;56(11):1565–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toner M, Irimia D. Blood-on-a-chip. Annual Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.011205.135108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burg TP, et al. Weighing of biomolecules, single cells and single nanoparticles in fluid. Nature. 2007;446:1066–1069. doi: 10.1038/nature05741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waggoner PS, Tan CP, Craighead HG. Microfluidic integration of nanomechanical resonators for protein analysis in serum. Sensors and Actuators B. 2010;150(2):550–555. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arlett JL, Myers EB, Roukes ML. Comparative advantages of mechanical biosensors. Nature Nanotechnology. 2011;6:203–215. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park K, Millet LJ, Huan, Kim N, Jin X, Popescu G, Aluru N, Hsia KJ, Bashir R. Measurement of Adherent Cell Mass and Growth’. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. 2010 Nov 30;107(48):20691–20696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011365107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez R, Morrisette D, Bashir R. IEEE/ASME Journal of Microelectro mechanical Systems. 2005;14:829–838. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhen G, Patolsk F, Cu Y, Wan WU, Liebe CM. Multiplexed electrical detection of cancer markers with nanowire sensor arrays. Nature Biotechnology. 2005;23(10):1294–1302. doi: 10.1038/nbt1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaster Richard S, Hall Drew A, Nielsen Carsten H, Osterfeld Sebastian J, Yu Heng, Mach Kathleen E, Wilson Robert J, Murmann Boris, Liao Joseph C, Gambhir Sanjiv S, Wang Shan X. Matrix-insensitive protein assays push the limits of biosensors in medicine. Nature Medicine. 2009;15:1327–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm.2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins N, Sridhar S, Cheng X, Chen G, Toner M, Rodriguez W, Bashir R. A microfabricated electrical differential counter for the selective enumeration of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1437. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00556h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulter WH. Means for counting particles suspended in a fluid. 2656508. US Pat. 1953

- 15.Ledis S, Crews H, Fischer T, Sena T. Lysing reagent system for isolation, identification and/or analysis of leukocytes from whole blood samples. 5155044. US Pat. 1992

- 16.van Berkel C, Gwyer J, Deane S, Green N, Holloway J, Hollis V, Morgan H. Integrated systems for rapid point of care (PoC) blood cell analysis. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1249–22. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00587h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyden S. Chemotactic effect of mixtures of antibody and antigen on polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1962;115(3):453–466. doi: 10.1084/jem.115.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeon NL, Baskaran H, Dertinger SK, Whitesides GM, Van de Water L, Toner M. Neutrophil chemotaxis in linear and complex gradients of interleukin-8 formed in a microfabricated device. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(8):826–830. doi: 10.1038/nbt712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irimia D. Microfluidic Technologies for Temporal Perturbations of Chemotaxis. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2010;12:259–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tharp WG, Yadav R, Irimia D, Upadhyaya A, Samadani A, et al. Neutrophil chemorepulsion in defined interleukin-8 gradients in vitro and in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:539–54. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0905516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irimia D, Liu SY, Tharp WG, Samadani A, Toner M, Poznansky MC. Microfluidic system for measuring neutrophil migratory responses to fast switches of chemical gradients. Lab Chip. 2006;6:191–98. doi: 10.1039/b511877h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzmark P, Campbell K, Wang F, Wong K, El-Samad H, et al. Bound attractant at the leading vs. the trailing edge determines chemotactic prowess. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13349–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705889104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal N, Toner M, Irimia D. Neutrophil Migration Assay from a Drop of Blood. Lab Chip. 2008;8:2054–2061. doi: 10.1039/b813588f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler KL, Ambravaneswaran V, Agrawal N, Bilodeau M, Toner M, Tompkins RG, Fagan S, Irimia D. Burn Injury Inhibits Neutrophil Chemotaxis in Microfluidic Devices. PLOS One. 2010;5(7):e11921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyvantsson I, Vu E, Lamers C, Echeverria D, Worzella T, Echeverria V, Skoien A, Hayes S. Image-based analysis of primary human neutrophil chemotaxis in an automated direct-viewing assay. J Immunol Methods. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang L, Cheng X, Liu Y, Bashir R. Lab-on-a-chip Impedance Detection of Microbial and Cellular Activity. In: Yaakov Nahmias, Bhatia Sangeeta., editors. “Microdevices in Biology and Medicine” (Methods in Bioengineering Book Series) Artech House; Boston, MA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhattacharya Shantanu, Salamat Shuaib, Morisette Dallas, Banada Padmapriya, Akin Demir, Liu Yi-Shao, Bhunia Arun K, Ladisch Michael, Bashir Rashid. PCR based-detection in a micro-fabricated platform. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1130–1136. doi: 10.1039/b802227e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu M, Stott S, Toner M, Maheswaran M, Haber D. Circulating tumor cells: approaches to isolation and characterization. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:373–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maheswaran S, Sequist LV, Nagrath S, Ulkus L, Brannigan B, Collura CV, Inserra E, Diederichs S, Iafrate AJ, Bell DW, et al. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:366–377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, Smith MR, Kwak EL, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007;450:1235–1239. doi: 10.1038/nature06385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stott SL, Lee RJ, Nagrath S, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Ulkus L, Inserra EJ, Ulman M, Springer S, Nakamura Z, et al. Isolation and characterization of circulating tumor cells from localized and metastatic prostate cancer patients. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:25ra23. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stott SL, Hsu CH, Tsukrov DI, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Waltman BA, Rothenberg SM, Shah AM, Smas ME, Korir GK, et al. Isolation of circulating tumor cells using a microvortex-generating herringbone-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18392–18397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012539107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]