Abstract

Chyluria is endemic in the Gangetic belt of India with an average of 90 cases treated annually at our institute. It is almost exclusively caused by Wuchereria bancrofti in tropical areas. Chylomicrons and triglycerides are lost in the urine from an abnormal lymphourinary fistula due to obstructive lymphatic stasis, most commonly at the renal pelvis. It is a distressingly recurrent condition with multiple exacerbations and remissions over years. Severe weakness, weight loss and haematuria occur in some patients. Diagnosis can be made by visual examination of milky urine along with the ether test of urine for chylomicrons. Intravenous urography is used to locate the site of the fistula, although the detection rate is poor. Treatment starts with conservative measures such as a high-protein low-fat diet and diethylcarbamazine therapy. In cases where conservative measures fail, endoscopic sclerotherapy (renal pelvic instillation of silver nitrate, povidone iodine or others) and surgical therapy are used.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman presented with chief complains of milky white urine accompanied by haematuria for the past 2 months along with severe weakness and weight loss. On examination the patient was severely dehydrated and cachexic. Her past history was significant for several similar episodes over the past 5 years. Some of the attacks had required treatment by drugs and others had spontaneously resolved. The patient was a resident of a village in the Jamui district of Bihar, India and often spent the summer nights sleeping outdoors. She described her village as a ‘muddy pond’ and ‘having more mosquitoes than stars in the sky’. There was a history of similar disease in her community. The patient was admitted and fluids and parenteral nutrition were administered. An early morning urine sample was collected after administering a fatty meal. On the ether test, the urine turned transparent and microscopic examination revealed chylomicrons. The patient's general condition improved. In view of her long history and the severity of the disease, she was treated with renal pelvic instillation of sclerosant (RPIS) using 5% povidone iodine and 50% dextrose. She was advised to abstain from dietary fats.

The patient was informed that the disease was spread by mosquito bites. The patient's village was about 300 km from our hospital. Although she had gone to her local health facility for treatment, this was the first time she had been evaluated and diagnosed. The patient was advised to attend regular follow-up visits at 2-monthly intervals at our hospital and to avoid mosquito breeding at her home and at the community level. After 2 months the patient presented in a healthy state and told us that her family had started using mosquito nets and had removed water pools from around her home. She was instructed to contact the local authorities regarding various health schemes running in her area and to be a part of it.

Global health problem list

Proper diagnosis of chyluria

Dietary advice and drug therapy

Administering sclerotherapy

Proper dose, agent and procedure for sclerotherapy

Surgical therapy for chyluria—which to choose, whom to choose

Mass chemoprophylaxis in endemic areas

Proper sanitation and mosquito control

Global health problem analysis

Introduction

Chyluria has been rampant in our country, especially in the Gangatic belt, since time immemorial. The great Indian sage Charak described it as ‘suklameha’ in 300 BC. It is endemic in south-east Asia, China, India, Taiwan and parts of Australia and Africa. In tropical countries more than 95% of it is caused by parasitic infestation with Wuchereria bancrofti. The parasite is spread by mosquitoes of the genera Anopheles, Culex and Aedes. Water-logged areas promote the growth of these mosquitoes.1 Chyluria occurs in 2% of filarial-infested patients.2 Besides W bancrofti, other parasitic causes include Eustrongylus gigas, Taenia echinococcus, Taenia nana and malarial parasites. Other non-parasitic causes include congenital obstruction, lymphangioma, trauma, radiation, malignancy and following surgery.3

Aetiopathogenesis

Chyluria is the passage of intestinal lymph in the urine. The pathophysiology of chyluria involves obstruction or dilation of the retroperitoneal lymphatics.4 The retroperitoneal lymphatics include a number of lymphatic trunks draining the kidneys and intestinal lymphatics draining the intestine, pancreas and spleen. All these lymphatics drain into the cisterna chyli. The aetiopathogenesis is not well known. There are two theories:

Obstructive theory: the parasitic infections lead to obliterative lymphangitis and lymphatic hypertension which leads to varicosities and collaterals leading to backflow of intestinal chyle.

Regurgitative theory: regurgitation of chyle from the cisterna chyli or large intestinal trunks into the renal lymphatics leads to rupture of these lymphatics into the renal calyces or pelvis.

Grading

Chyluria is graded according to the mode of presentation: grade 1 is milky white urine; grade 2 is white clots or episodes of clot retention; and grade 3 is haematochyluria.5

Diagnosis

Urine examination

Chyluria can be diagnosed by examining a freshly voided sample of morning urine. A fatty meal should be taken before voiding. On visual examination, chylous urine is milky in appearance and may contain fibrin and blood clots. The urine becomes clear on adding ether and bright red with ingestion of Sudan III mixed butter. Analysis of urine reveals chylomicrons and triglycerides. Estimation of urinary chylomicrons is the most specific and sensitive test for chyluria.4

Haematological examination

A haemogram typically shows eosinophilia.

Imaging

Intravenous urography, retrograde pyelography and lymphangiography are used to locate the lymphourinary fistulas. Recently, magnetic resonance pyelography and lymphoscintigraphy have also been used.6 If available, lymphangiography is an excellent diagnostic modality. It can demonstrate the site, calibre and number of fistulous communications. Findings include lymphourinary fistula at the level of the kidneys, ureters or bladder. The presence of lymphangiectesias may be noted. In 40% of cases contrast enters the pelvicalyceal system. Lymphangiography is rarely used nowadays as it is an invasive, time-consuming and technically demanding procedure. Lymphoscintigraphy is a non-invasive technique which uses Tc-99 m diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid radionucleotides to demonstrate lymphourinary fistulas.4

Immunological examination

Filarial antigen detection in the urine and serum can be done with ELISA.7

The differential diagnosis of milky urine includes phosphaturia (dissolves with 10% acetic acid), amorphous urates, gross pyuria, lipiduria, pseudochylous urine and caseouria due to renal tuberculosis.

Treatment

Although chyluria is not life-threatening, 5–10% of patients develop severe weight loss and weakness and require admission to hospital and parenteral nutrition.

Conservative treatment

Patients with mild chyluria are managed with dietary restriction and drugs. Dietary restriction of long-chain triglycerides along with the use of medium-chain triglycerides is advocated. Dietary triglyceride restriction leads to prevention of chylomicron production by enterocytes and chyluria cessation. Medium-chain triglycerides (<12 carbon atoms) are directly absorbed via the portal circulation, bypassing the lymphatics.8 The use of coconut oil, which contains medium-chain triglycerides, is promoted. An Indian study has found that both the commonly used cooking medium in northern India ghee (clarified unsalted butter) and mustard oil contribute to chyluria, with ghee being the worst offender.9 Dietary therapy is combined with drugs. The commonly used drugs include diethylcarbamazine (DEC) (6 mg/kg/day for 21 days), albendazole (400–800 mg/day for 10–14 days), ivermectin (6–12 mg stat, repeated after 3 weeks) and benzathine penicillin (1.2 million units weekly for 12 weeks). We use a combination of drugs in most cases. DEC is the most widely used drug and has a selective action on microfilariae, which is the larval stage. Its action appears to be a change to the larval membrane so that they are phagocytosed by macrophages. Albendazole is a benzimidazole congener that kills parasites by inhibiting microtubular proteins. Ivermectin as a single dose has a potent action on parasites by blocking their neurogenic transmission. Rest and abdominal binders have also been found useful.

Two or three courses of drug therapy are given to the patient. Conservative management has a success rate of more than 70%. The factors associated with a poor response to treatment include higher grade disease, pretreatment with drugs and higher urinary cholesterol at baseline.10

Sclerotherapy

For patients not responding to conservative therapy, RPIS is used. It is based on the observation that the lymphourinary fistula is most commonly located at the renal pelvis. Injection of sclerosant here causes it to pass to the lymphatic channels and induce a chemical lymphatic reaction. The resultant oedema leads to blockade of the lymphatics and immediate relief to the patient. Permanent relief of chyluria occurs when the lymphatics heal by fibrosis. The procedure is performed under local anaesthesia or sedation. A fatty meal in the morning or previous night facilitates identification of the affected ureteric orifice. As the chyluria is intermittent, the orifice needs to be observed for 15 min or longer for diagnosis. Pressing the kidney through the abdominal wall also sometimes helps. A ureteric catheter is passed to the renal pelvis under radiological control and an amount of sclerosant equal to the renal pelvic capacity (7–10 mL) is injected. The instillation is done in the head-down position and continues until the patient experiences pain.11

The commonly used sclerosants include silver nitrate (0.1–1%), povidone iodine (0.2–5%), sodium iodide (15–25%), potassium bromide (10–25%), 50% dextrose, hypertonic saline (3%) or a combination of these. For instillation, an 8-hourly instillation for 3 days has been found to be superior to a weekly instillation for 6 weeks.12

Silver nitrate

The most extensively studied agent in the past was silver nitrate (0.1–1%); 2 g of silver nitrate is dissolved in 200 mL water and kept in a dark bottle to protect it from sunlight as silver nitrate becomes unstable on exposure to sunlight. Freshly prepared solution is needed every time, so it must be procured 8–24 h before the procedure and autoclaved. It can precipitate with normal saline to form insoluble silver chloride salt which can lead to ureteric obstruction. It is a water insoluble compound. These problems have led to a decrease in its use.12 One death after bilateral instillation has been reported.13

Povidone iodine

Povidone iodine is believed to be the most commonly used agent at present. It is stable at room temperature, water soluble and easily available. Chemically it is polyvinyl pyrrolidone and releases iodine slowly. It also has antibacterial, antifungal and antiseptic properties. It has been used in a concentration of 0.2–5%.14 We have been using a mixture of 5% povidone iodine and 50% dextrose15 for 5 years with good results and have not observed any strictures, deaths or other untoward incidents. Our cure rate at 6 months exceeds 90% (table 1). Patients who fail one course of sclerotherapy should be treated with a second course. Singh and Srivastava11 have shown that the time to failure has a prognostic significance, with immediate failure being associated with a lower chance of final success.

Table 1.

Results of patients with chyluria treated at our institute by sclerotherapy with 5% povidone iodine and 50% dextrose over a 1-year period (January to December 2013)

| Characteristics | N |

|---|---|

| No of patients | 97 |

| Age distribution (years) | |

| <20 | 24 |

| 21–39 | 45 |

| 40–60 | 28 |

| Male/female | 61/36 |

| Mean follow-up (months) | 6 (range 3–11) |

| Success rate | 92.7% |

| Major complications | |

| Flank pain | 27 |

| Haematuria | 18 |

| Chyluria persisting | 7 |

Surgical therapy

Patients who do not respond to two or three courses of RPIS are labelled as ‘refractory chyluria’ and are considered for surgical therapy. Other indications for surgery include extensive weight loss, hypoproteinaemia, anasarca, recurrent clot retention, haematochyluria, recurrent urinary tract infections secondary to chyluria, altered immune status and psychological disturbances.16 Hemal et al17 classified chyluria into the following three grades based on involvement of the calyces on retrograde pyelography (RGP):

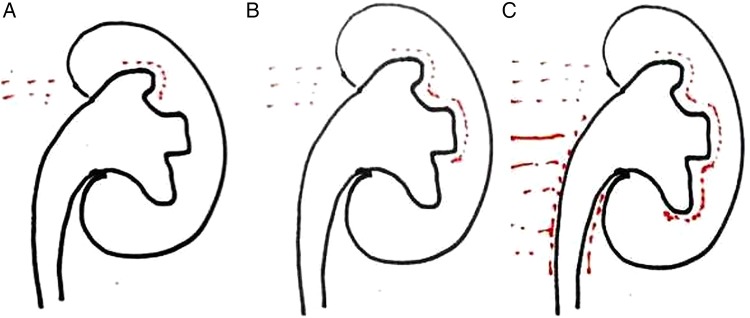

Mild chyluria: involvement of a single calyx on RGP (figure 1A).

Moderate chyluria: involvement of two or more calyces on RGP (figure 1B).

Severe chyluria: involvement of most calyces with/without involvement of the ureter on RGP (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Drawing showing amount of calyx involvement marked by dotted red line. (A) Involvement of single calyx. (B) Involvement two calyces. (C) Involvement of most of the calyx plus the ureter.

They advocated surgery in failed cases of mild to moderate grade and in those with severe grade of chyluria.

The operations described for chyluria include chylolymphatic disconnection, lymphovenous anastomosis, retroperitoneal lymphovenous anastomosis, transinguinal spermatic lymphovenous anastomosis, inguinal lymph node–saphenous venous anastomosis and autotransplantation or nephrectomy.

Chylolymphatic disconnection

Chylolymphatic disconnection is the most commonly performed procedure. It was first described by Ketamine in 1952. This operation can be done by a flank incision or laparoscopically through either the transperitoneal or retroperitoneal route. Before surgery patients are put on high-fat diet for 24–36 h to facilitate intraoperative identification of the lymphatics. Methylene blue dye is also used for the same purpose. Five procedures can be used:

Nephrolympholysis: the kidney is dissected free from its surrounding perirenal fascia.

Hilar stripping: this includes skeletonisation of the renal vessels and ligating the perihilar lymphatics.

Ureterolympholysis: this includes stripping of the ureteral lymphatics downward to the common iliac vessels.

Fasciectomy: this includes removal of perirenal tissues and fat.

Nephropexy: the kidney is fixed to the psaos muscle at its upper, middle and lower poles to restrict its hypermobility.

After dividing the renal fascia, the lymphatics around the renal hilum and upper ureter are routinely stripped and ligated in most cases.18

Patna operation

The original ‘Patna operation’ described the concept of ‘ureter in a lymphatic tunnel’ and utilised lymphatic disconnection of the abdominal ureter up to the bladder. However, disconnection up to the bladder is not used nowadays as most of the leak is localised to the renal pelvis. In case of recurrence or if radiological studies demonstrate lymph leak from the ureter, complete stripping is performed.19

Lymphovenous anastomosis

Lymphovenous anastomosis is a more physiological way of treating chyluria as it diverts the lymph flow into the venous system and decreases intralymphatic pressure. The thin calibre of lymph vessels makes the procedure technically demanding and requires microsurgical expertise. The anastomosis can be done retroperitoneally, at the inguinal area or anastomosis of the inguinal lymph node with the saphenous veins. These anastomoses are more superficial and hence are preferred in older and weaker patients who would not tolerate lymphatic ligation. In women, the vessel calibre is thinner and hence the anastomosis is done at the level of the dorsum of the foot, leg or thigh while, in men, the inguinal region is preferred. Patency of the anastomosis is essential for a successful operation, and it may take up to 6 months to show results. It is advisable to do at least two anastomoses to enhance lymphatic flow. If the diameter of the lymphatics is <0.1 mm, a vein of corresponding diameter is anastomosed to a bunch of lymphatics.16

Retroperitoneal lymph node anastomosis

This technique was originally described by Cockett and Goodwin.20 Operating in the retroperitoneum can be associated with problems of a deep-seated operative field, risk of renal pedicle injury, risk of renal artery stenosis and renovascular injury.

Transinguinal spermatic lymphovenous anastomosis

This procedure is performed via an inguinal incision. Methylene blue is injected to stain the lymphatics and they are anastomosed to spermatic veins of similar calibre using 10-0 nylon.21

Inguinal lymph node–saphenous vein anastomosis

The inguinal lymph node is anastomosed to the saphenous vein. The procedure provides a wide anastomosis for free passage of lymph into the venous system and avoids damage to the efferent and afferent lymphatic vessels.22

Autotransplantation and nephrectomy

Autotransplantation and even nephrectomies have been described for severe unrelenting chyluria.23 We have no experience with these procedures and have never had a requirement for them.

Stepwise approach to the management of patients with chyluria

Suspected chyluria (white urine, haematuria)

Urinary triglycerides, urinary chylomicrons present

Dietary therapy, medium-chain triglycerides, DEC

Recurrence

Intravenous urography, CT scan, MRI

RPIS: betadine, silver nitrate (up to two courses)

Chylolymphatic disconnection (open or laparoscopic)

Recurrence

Lymphovenous, lymph node–venous anastomosis

Nephrectomy, autotransplantation

Mass chemoprophylaxis

An important strategy in the control of tropical lymphatic diseases such as filariasis includes mass chemoprophylaxis in endemic areas. Globally, the preferred regime is DEC 6 mg/kg along with albendazole 400 mg. In India a single dose of DEC is used. It is estimated that chemoprophylaxis has to reach 90% of the population for elimination of filariasis.24

Environmental measures

Filariasis is transmitted by mosquito bite of the genera Aedes, Anopheles and Culex. These mosquitoes thrive around sources of stagnant water. Community and government participation to clean up the surroundings is essential to control the disease. The government carries out periodic spraying of dichlorodiphenytrichloroethane (DDT) and other disinfectants in endemic areas. Other personal measures to combat mosquitoes include use of mosquito nets and repellents.

Conclusion

Chyluria caused by lymphatic filariasis is a public health problem in our region. It is essentially a benign disease which can be effectively controlled by public awareness, drugs and dietary restrictions. A small proportion of patients have severe and unrelenting disease which requires surgical intervention. Filariasis as an endemic tropical disease requires medical treatment as well as community participation for control.

Learning points.

Chyluria is caused in most cases by mosquito-borne Wuchereria bancrofti.

It can be diagnosed by urine examination for chyle and chylomicrons.

Most cases can be controlled by diet and drug therapy.

A small proportion have severe, unrelenting and refractory disease which requires surgery or sclerotherapy.

Prevention of mosquito bites is essential to prevent the spread of this disease.

Footnotes

Contributors: RKS: manuscript design, preparation, editing. NR: manuscript design, preparation, editing. NS: manuscript design, preparation, editing. KA: final editing.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pandey AP, Ansari MS. Recurrent chyluria. Indian J Urol 2006;22:56–8. 10.4103/0970-1591.24657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond E, Schapira HE. Chyluria—a review of the literature. Urology 1985;26:427–31. 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90147-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalela D. Issues in etiology and diagnosis making of chyluria. Indian J Urol 2005;21:18–23. 10.4103/0970-1591.19545 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh I, Dargan P, Sharma N. Chyluria—a clinical and diagnostic stepladder algorithm with review of literature. Indian J Urol 2004;20:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suri A, Kumar A. Chyluria—SGPGI experience. Indian J Urol 2005;21:59–62. 10.4103/0970-1591.19554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goel A, Goyal NK, Parihar A et al. Magnetic resonance-retrograde pyelography: a novel technique for evaluation of chyluria. Indian J Urol 2014;30:115–16. 10.4103/0970-1591.124221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng H, Tay Z, Fang R et al. Application of immuno-chromatographic test for diagnosis and surveillance of bancroftian filariasis. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 1998;16:168–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashim SA, Roholt HB, Babayan VK et al. Treatment of chyluria and chylothorax with medium-chain triglyceride. N Engl J Med 1964;270:756–61. 10.1056/NEJM196404092701502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh LK, Datta B, Dwivedi US et al. Dietary fats and chyluria. Indian J Urol 2005;21:50–4. 10.4103/0970-1591.19552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal NK, Goel A, Sankhwar S et al. Factors affecting response to medical management in patients of filarial chyluria: a prospective study. Indian J Urol 2014;30:23–7. 10.4103/0970-1591.124201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh KJ, Srivastava A. Nonsurgical management of chyluria (sclerotherapy). Indian J Urol 2005;21:55–8. 10.4103/0970-1591.19553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabnis RB, Punekar SV, Desai RM et al. Instillation of silver nitrate in the treatment of chyluria. Br J Urol 1992;70:660–2. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1992.tb15839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandhani A, Kapoor R, Gupta RK et al. Can silver nitrate instillation for the treatment of chyluria be fatal? Br J Urol 1998;82:926–7. 10.1046/j.1464-410X.1998.00839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanmugam TV, Prakash JV, Sivashankar G. Povidone iodine used as a sclerosing agent in the treatment of chyluria. Br J Urol 1998;82:587 10.1046/j.1464-410X.1998.00861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nandy PR, Dwivedi US, Vyas N et al. Povidone iodine and dextrose solution combination sclerotherapy in chyluria. Urology 2004;64:1107–9. 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viswaroop B, Gopalakrishnan G. Open surgery for chyluria. Indian J Urol 2005;21:31–4. 10.4103/0970-1591.19548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemal AK, Kumar M, Wadhwa SN. Retroperitoneoscopic nephrolympholysis and ureterolysis for management of intractable filarial chyluria. J Endourol 1999;13:507–11. 10.1089/end.1999.13.507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta NP. Retroperitoneoscopic management of intractable chyluria. Indian J Urol 2005;21:63–5. 10.4103/0970-1591.19555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad PB, Choudhary DK, Barnwal SN et al. Periureteric lympho-venous stripping in cases of chylohaematuria: report of 15 cases. IJS 1977;39:607–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cockett AT, Goodwin WE. Chyluria: attempted surgical treatment by lymphatic-venous anastomosis. J Urol 1962;88:566–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao WP, Hou LQ, Shen JL. Summary and prospects of fourteen years’ experience with treatment of chyluria by microsurgery. Eur Urol 1988;15:219–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou LQ, Liu QY, Kong QY et al. Lymphonodovenous anastomosis in the treatment of chyluria. Chin Med J Eng 1991;104:392–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang CY, Yu HN, Lapides CH. Surgical treatment of chyluria. J Urol 1973;109:299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nandha B, Sadanandane C, Jambulingam P et al. Delivery strategy of mass annual single dose DEC administration to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in the urban areas of Pondicherry, South India: 5 years of experience. Filaria J 2007;6:7 10.1186/1475-2883-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]